Difference between revisions of "Nanotechnology" - New World Encyclopedia

m (small edit to the first paragraph) |

(→Current research: deleted copyrighted image) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{redirect|Nanotech}} | |

| − | + | [[Image:C60a.png|thumb|right|200px|Buckminsterfullerene C<sub>60</sub>, also known as the buckyball, is the simplest of the [[Allotropes of carbon|carbon structures]] known as [[fullerene]]s. Members of the fullerene family are a major subject of research falling under the nanotechnology umbrella.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Nanotechnology''' is a field of applied science and technology covering a broad range of topics. The main unifying theme is the control of matter on a scale smaller than 1 [[micrometre]], normally between 1-100 nanometers, as well as the fabrication of devices on this same length scale. It is a highly [[Interdisciplinarity|multidisciplinary]] field, drawing from fields such | |

| + | as [[colloid]]al science, [[Semiconductor device|device physics]], and [[supramolecular chemistry]]. Much speculation exists as to what new science and technology might result from these lines of research. Some view nanotechnology as a marketing term that describes pre-existing lines of research applied to the sub-micron size scale. | ||

| − | + | Despite the apparent simplicity of this definition, nanotechnology actually encompasses diverse lines of inquiry. Nanotechnology cuts across many disciplines, including [[colloid]]al science, [[chemistry]], [[applied physics]], [[materials science]], and even [[Mechanical engineering|mechanical]] and [[electrical engineering]]. It could variously be seen as an extension of existing sciences into the nanoscale, or as a recasting of existing sciences using a newer, more modern term. Two main approaches are used in nanotechnology: one is a "bottom-up" approach where materials and devices are built from [[Molecule|molecular]] components which [[self-assembly|assemble themselves]] chemically using principles of [[molecular recognition]]; the other being a "top-down" approach where nano-objects are constructed from larger entities without atomic-level control. | |

| − | The | + | The impetus for nanotechnology has stemmed from a renewed interest in colloidal science, coupled with a new generation of analytical tools such as the [[atomic force microscope]] (AFM), and the [[scanning tunneling microscope]] (STM). Combined with refined processes such as [[electron beam lithography]] and [[molecular beam epitaxy]], these instruments allow the deliberate manipulation of nanostructures, and in turn led to the observation of novel phenomena. The manufacture of polymers based on molecular structure, or the design of computer chip layouts based on surface science are examples of nanotechnology in modern use. Despite the great promise of numerous nanotechnologies such as [[quantum dots]] and [[nanotubes]], real applications that have moved out of the lab and into the marketplace have mainly utilized the advantages of colloidal nanoparticles in bulk form, such as [[suntan lotion]], [[cosmetics]], [[protective coatings]], and stain resistant clothing. |

| − | + | {{Nanotech}} | |

| − | + | == Origins == | |

| − | + | {{main|History of nanotechnology}} | |

| − | + | The first distinguishing concepts in nanotechnology (but predating use of that name) was in "[[There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom]]," a talk given by physicist [[Richard Feynman]] at an [[American Physical Society]] meeting at [[Caltech]] on [[December 29]], [[1959]]. Feynman described a process by which the ability to manipulate individual atoms and molecules might be developed, using one set of precise tools to build and operate another proportionally smaller set, so on down to the needed scale. In the course of this, he noted, scaling issues would arise from the changing magnitude of various physical phenomena: gravity would become less important, surface tension and [[Van der Waals force|Van der Waals attraction]] would become more important, etc. This basic idea appears feasible, and [[exponential assembly]] enhances it with [[parallelism]] to produce a useful quantity of end products. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The term "nanotechnology" was defined by [[Tokyo Science University]] Professor [[Norio Taniguchi]] in a [[1974]] paper (N. Taniguchi, "On the Basic Concept of 'Nano-Technology'," Proc. Intl. Conf. Prod. Eng. Tokyo, Part II, Japan Society of Precision Engineering, 1974.) as follows: "'Nano-technology' mainly consists of the processing of, separation, consolidation, and deformation of materials by one atom or by one molecule." In the 1980s the basic idea of this definition was explored in much more depth by [[Eric Drexler|Dr. K. Eric Drexler]], who promoted the technological significance of nano-scale phenomena and devices through speeches and the books [[Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology]] (1986) and ''[http://www.e-drexler.com/d/06/00/Nanosystems/toc.html Nanosystems: Molecular Machinery, Manufacturing, and Computation],'' (1998, ISBN 0-471-57518-6), and so the term acquired its current sense. | |

| − | + | Nanotechnology and nanoscience got started in the early 1980s with two major developments; the birth of [[Cluster (physics)|cluster]] science and the invention of the [[scanning tunneling microscope]] (STM). This development led to the discovery of [[fullerenes]] in 1986 and [[carbon nanotubes]] a few years later. In another development, the synthesis and properties of semiconductor [[nanocrystal]]s was studied. This led to a fast increasing number of metal oxide nanoparticles of [[quantum dots]]. The [[atomic force microscope]] was invented five years after the STM was invented. The AFM uses atomic force to see the atoms. | |

| − | == | + | == Fundamental concepts == |

| − | |||

| − | + | {{wikibookspar||The Opensource Handbook of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology}} | |

| − | + | One nanometer (nm) is one billionth, or 10<sup>-9</sup> of a meter. For comparison, typical carbon-carbon [[bond length]]s, or the spacing between these atoms in a molecule, are in the range .12-.15 nm, and a [[DNA]] double-helix has a diameter around 2 nm. On the other hand, the smallest [[Cell (biology)|cellular]] lifeforms, the bacteria of the genus [[Mycoplasma]], are around 200 nm in length. | |

| − | == | + | === Larger to smaller: a materials perspective === |

| − | |||

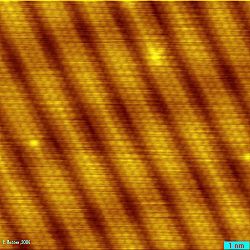

| − | + | [[image:Atomic_resolution_Au100.JPG|left|250px|thumb|Image of [[Surface reconstruction|reconstruction]] on a clean [[Gold|Au]]([[Miller index|100]]) surface, as visualized using [[scanning tunneling microscopy]]. The individual [[atom]]s composing the surface are visible.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | {{main|Nanomaterials}} | |

| − | + | A unique aspect of nanotechnology is the vastly increased ratio of surface area to volume present in many nanoscale materials which opens new possibilities in surface-based science, such as [[catalysis]]. A number of physical phenomena become noticeably pronounced as the size of the system decreases. These include [[statistical mechanics|statistical mechanical]] effects, as well as [[quantum mechanics|quantum mechanical]] effects, for example the “[[quantum]] size effect” where the electronic properties of solids are altered with great reductions in particle size. This effect does not come into play by going from macro to micro dimensions. However, it becomes dominant when the nanometer size range is reached. Additionally, a number of [[physical properties]] change when compared to macroscopic systems. One example is the increase in surface area to volume of materials. This catalytic activity also opens potential risks in their interaction with [[biomaterial]]s. | |

| − | + | Materials reduced to the nanoscale can suddenly show very different properties compared to what they exhibit on a macroscale, enabling unique applications. For instance, opaque substances become transparent (copper); inert materials become catalysts (platinum); stable materials turn combustible (aluminum); solids turn into liquids at room temperature (gold); insulators become conductors (silicon). A material such as [[gold]], which is chemically inert at normal scales, can serve as a potent chemical [[catalyst]] at nanoscales. Much of the fascination with nanotechnology stems from these unique quantum and surface phenomena that matter exhibits at the nanoscale. | |

| − | + | === Simple to complex: a molecular perspective === | |

| − | + | {{main|Molecular self-assembly}} | |

| − | + | Modern [[Chemical synthesis|synthetic chemistry]] has reached the point where it is possible to prepare small [[molecule]]s to almost any structure. These methods are used today to produce a wide variety of useful chemicals such as [[drug|pharmaceuticals]] or commercial [[polymer]]s. This ability raises the question of extending this kind of control to the next-larger level, seeking methods to assemble these single molecules into [[Supramolecular assembly|supramolecular assemblies]] consisting of many molecules arranged in a well defined manner. | |

| − | + | These approaches utilize the concepts of [[molecular self-assembly]] and/or [[supramolecular chemistry]] to automatically arrange themselves into some useful conformation through a [[bottom-up]] approach. The concept of [[molecular recognition]] is especially important: molecules can be designed so that a specific conformation or arrangement is favored due to [[Noncovalent bonding|non-covalent]] [[intermolecular force]]s. The Watson-Crick [[Base pair|basepairing]] rules are a direct result of this, as is the specificity of an [[enzyme]] being targeted to a single [[Substrate (biochemistry)|substrate]], or the specific [[Protein folding|folding of the protein]] itself. Thus, two or more components can be designed to be complementary and mutually attractive so that they make a more complex and useful whole. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Such bottom-up approaches should, broadly speaking, be able to produce devices in parallel and much cheaper than top-down methods, but could potentially be overwhelmed as the size and complexity of the desired assembly increases. Most useful structures require complex and thermodynamically unlikely arrangements of atoms. Nevertheless, there are many examples of self-assembly based on molecular recognition in [[biology]], most notably [[Base pair|Watson-Crick basepairing]] and [[enzyme]]-[[Substrate (biochemistry)|substrate]] interactions. The challenge for nanotechnology is whether these principles can be used to engineer novel constructs in addition to natural ones. | |

| − | + | === Molecular nanotechnology: a long-term view === | |

| + | Molecular nanotechnology, sometimes called molecular manufacturing, is a term given to the concept of engineered nanosystems (nanoscale machines) operating on the molecular scale. It is especially associated with the concept of a [[molecular assembler]], a machine that can produce a desired structure or device atom-by-atom using the principles of [[mechanosynthesis]]. Manufacturing in the context of productive nanosystems is not related to, and should be clearly distinguished from, the conventional technologies used to manufacture nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes and nanoparticles. | ||

| − | + | When the term "nanotechnology" was independently coined and popularized by [[Eric Drexler]] (who at the time was unaware of an [[History of nanotechnology|earlier usage]] by [[Norio Taniguchi]]) it referred to a future manufacturing technology based on molecular machine systems. The premise was that molecular-scale biological analogies of traditional machine components demonstrated molecular machines were possible: by the countless examples found in biology, it is known that billions of years of evolutionary feedback can produce sophisticated, [[stochastic]]ally optimised biological machines. It is hoped that developments in nanotechnology will make possible their construction by some other means, perhaps using [[biomimetic]] principles. However, Drexler and [http://www.crnano.org/developing.htm other researchers] have proposed that advanced nanotechnology, although perhaps initially implemented by biomimetic means, ultimately could be based on mechanical engineering principles, namely, a manufacturing technology based on the mechanical functionality of these components (such as gears, bearings, motors, and structural members) that would enable programmable, positional assembly to atomic specification ([http://www.imm.org/PNAS.html PNAS-1981]). The physics and engineering performance of exemplar designs were analyzed in Drexler's book [http://www.e-drexler.com/d/06/00/Nanosystems/toc.html Nanosystems]. But Drexler's analysis is very qualitative and does not address very pressing issues, such as the "fat fingers" and "Sticky fingers" problems. In general it is very difficult to assemble devices on the atomic scale, as all one has to position atoms are other atoms of comparable size and stickyness. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Another view, put forth by [http://www.cnsi.ucla.edu/institution/personnel?personnel%5fid=105488 Carlo Montemagno], is that future nanosystems will be hybrids of silicon technology and biological molecular machines. Yet another view, put forward by the late [[Richard Smalley]], is that mechanosynthesis is impossible due to the difficulties in mechanically manipulating individual molecules. This led to an [http://pubs.acs.org/cen/coverstory/8148/8148counterpoint.html exchange of letters] in the [[American Chemical Society|ACS]] publication [[Chemical & Engineering News]] in 2003. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Though biology clearly demonstrates that molecular machine systems are possible, non-biological molecular machines are today only in their infancy. Leaders in research on non-biological molecular machines are Dr. Alex Zettl and his colleagues at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories and UC Berkeley. They have constructed at least three distinct molecular devices whose motion is controlled from the desktop with changing voltage: a nanotube [[nanomotor]], a [http://www.physics.berkeley.edu/research/zettl/pdf/312.NanoLett5regan.pdf molecular actuator], and a [http://www.lbl.gov/Science-Articles/Archive/sabl/2005/May/Tiniest-Motor.pdf nanoelectromechanical relaxation oscillator]. An experiment indicating that positional molecular assembly is possible was performed by Ho and Lee at [[Cornell University]] in 1999. They used a scanning tunneling microscope to move an individual carbon monoxide molecule (CO) to an individual iron atom (Fe) sitting on a flat silver crystal, and chemically bound the CO to the Fe by applying a voltage. | |

| − | + | == Current research == | |

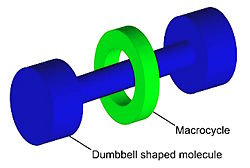

| + | [[Image:Rotaxane.jpg|thumbnail|250px|Graphical representation of a [[rotaxane]], useful as a molecular switch.]] | ||

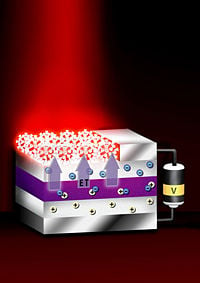

| + | [[Image:Achermann7RED.jpg|200px|thumb|right|This device transfers energy from nano-thin layers of [[quantum well]]s to [[nanocrystal]]s above them, causing the nanocrystals to emit visible light. [http://www.sandia.gov/news-center/news-releases/2004/micro-nano/well.html] ]] | ||

| − | + | As nanotechnology is a very broad term, there are many disparate but sometimes overlapping subfields that could fall under its umbrella. The following avenues of research could be considered subfields of nanotechnology. Note that these categories are fairly nebulous and a single subfield may overlap many of them, especially as the field of nanotechnology continues to mature. | |

| − | |||

| + | === Nanomaterials === | ||

| + | {{main|nanomaterials}} | ||

| + | This includes subfields which develop or study materials having unique properties arising from their nanoscale dimensions. | ||

| + | * '''[[Colloid]] science''' has given rise to many materials which may be useful in nanotechnology, such as [[carbon nanotube]]s and other [[fullerene]]s, and various [[nanoparticle]]s and [[nanorod]]s. | ||

| + | * [[Nanomaterials|Nanoscale materials]] can also be used for '''bulk applications'''; most present commercial applications of nanotechnology are of this flavor. | ||

| + | * Progress has been made in using these materials for medical applications; see '''[[Nanomedicine]]'''. | ||

| + | === Bottom-up approaches === | ||

| − | == | + | These seek to arrange smaller components into more complex assemblies. |

| − | {{ | + | * '''DNA Nanotechnology''' utilises the specificity of [[Base pair|Watson-Crick basepairing]] to construct well-defined structures out of [[DNA]] and other [[nucleic acid]]s. |

| − | * [[ | + | * More generally, '''[[molecular self-assembly]]''' seeks to use concepts of [[supramolecular chemistry]], and [[molecular recognition]] in particular, to cause single-molecule components to automatically arrange themselves into some useful conformation. |

| − | * [[ | + | |

| − | + | === Top-down approaches === | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | These seek to create smaller devices by using larger ones to direct their assembly. | |

| − | + | * Many technologies descended from conventional '''[[Semiconductor fabrication|solid-state silicon methods]]''' for fabricating [[microprocessor]]s are now capable of creating features smaller than 100 nm, falling under the definition of nanotechnology. [[Giant magnetoresistance]]-based hard drives already on the market fit this description, [http://www.nano.gov/html/facts/appsprod.html] as do [[atomic layer deposition]] (ALD) techniques. | |

| + | * Solid-state techniques can also be used to create devices known as '''[[nanoelectromechanical systems]]''' or NEMS, which are related to [[microelectromechanical systems]] or MEMS. | ||

| + | * [[Atomic force microscope]] tips can be used as a nanoscale "write head" to deposit a chemical on a surface in a desired pattern in a process called '''[[dip pen nanolithography]]'''. This fits into the larger subfield of [[nanolithography]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Functional approaches === | ||

| + | |||

| + | These seek to develop components of a desired functionality without regard to how they might be assembled. | ||

| + | * '''[[Molecular electronics]]''' seeks to develop molecules with useful electronic properties. These could then be used as single-molecule components in a nanoelectronic device. For an example see [[rotaxane]]. | ||

| + | * Synthetic chemical methods can also be used to create '''[[synthetic molecular motors]]''', such as in a so-called [[nanocar]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Speculative === | ||

| + | |||

| + | These subfields seek to [[Futures studies|anticipate]] what inventions nanotechnology might yield, or attempt to propose an agenda along which inquiry might progress. These often take a big-picture view of nanotechnology, with more emphasis on its [[Implications of nanotechnology|societal implications]] than the details of how such inventions could actually be created. | ||

| + | * '''[[Molecular nanotechnology]]''' is a proposed approach which involves manipulating single molecules in finely controlled, deterministic ways. This is more theoretical than the other subfields and is beyond current capabilities. | ||

| + | * '''[[Nanorobotics]]''' centers on self-sufficient machines of some functionality operating at the nanoscale. There are hopes for applying nanorobots in medicine <ref>{{cite journal |author=Ghalanbor Z, Marashi SA, Ranjbar B |title=Nanotechnology helps medicine: nanoscale swimmers and their future applications |journal=Med Hypotheses |volume=65 |issue=1 |pages=198-199 |year=2005 |pmid=15893147}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Kubik T, Bogunia-Kubik K, Sugisaka M. |title=Nanotechnology on duty in medical applications |journal=Curr Pharm Biotechnol. |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=17-33 |year=2005 |pmid=15727553}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Cavalcanti A, Freitas RA Jr. |title=Nanorobotics control design: a collective behavior approach for medicine |journal=IEEE Trans Nanobioscience |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=133-140 |year=2005 |pmid=16117021}}</ref>, while it might not be easy to do such a thing because of several drawbacks of such devices <ref>{{cite journal |author=Shetty RC|title=Potential pitfalls of nanotechnology in its applications to medicine: immune incompatibility of nanodevices |journal=Med Hypotheses |volume=65 |issue=5 |pages=998-9 |year=2005 |pmid=16023299}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Curtis AS. |title=Comment on "Nanorobotics control design: a collective behavior approach for medicine". |journal=IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=201-202 |year=2005 |pmid=16117028}}</ref>. Nevertheless, progress on innovative materials and methodologies has been demonstrated with some patents granted about new nanomanufacturing devices for future commercial applications, which also progressively helps in the development towards nanorobots with the use of embedded nanobioelectronics concept<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cavalcanti A, Shirinzadeh B, Freitas RA Jr., Kretly LC. |title= Medical Nanorobot Architecture Based on Nanobioelectronics |journal=[http://bentham.org/nanotec/ Recent Patents on Nanotechnology]. |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=1-10 |year=2007 |}}</ref>. | ||

| + | * '''[[Programmable matter]]''' based on [[artificial atom]]s seeks to design materials whose properties can be easily and reversibly externally controlled. | ||

| + | * Due to the popularity and media exposure of the term nanotechnology, the words '''[[picotechnology]]''' and '''[[femtotechnology]]''' have been coined in analogy to it, although these are only used rarely and informally. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Tools and techniques == | ||

| + | |||

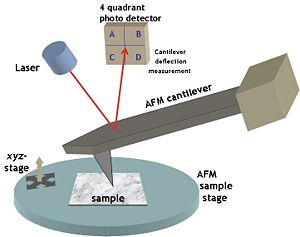

| + | [[Image:AFMsetup.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Typical [[Atomic force microscope|AFM]] setup. A [[Microfabrication|microfabricated]] [[cantilever]] with a sharp tip is deflected by features on a sample surface, much like in a [[phonograph]] but on a much smaller scale. A [[laser]] beam reflects off the backside of the cantilever into a set of [[photodetector]]s, allowing the deflection to be measured and assembled into an image of the surface.]] Another technique uses [[SPT™s (surface patterning tool)]] as the molecular “ink cartridge”. Each SPT is a microcantilever-based micro-fluidic handling device. SPTs contain either a single microcantilever print head or multiple microcantilevers for simultaneous printing of multiple molecular species. The integrated microfluidic network transports fluid samples from reservoirs located on the SPT through microchannels to the distal end of the cantilever. Thus SPTs can be used to print materials that include biological samples such as proteins, DNA, RNA, and whole viruses, as well as non-biological samples such as chemical solutions, colloids and particle suspensions. SPTs are most commonly used with molecular printers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nanotechnological techniques include those used for fabrication of nanowires, those used in semiconductor fabrication such as deep ultraviolet lithography, electron beam lithography, focused ion beam machining, nanoimprint lithography, atomic layer deposition, and molecular vapor deposition, and further including molecular self-assembly techniques such as those employing di-block copolymers. However, all of these techniques preceded the nanotech era, and are extensions in the development of | ||

| + | scientific advancements rather than techniques which were devised with the sole purpose of creating nanotechnology and which were results of nanotechnology research. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nanoscience and nanotechnology only became possible in the 1910s with the development of the first tools to measure and make nanostructures. But the actual development started with the discovery of electrons and neutrons which showed scientists that matter can really exist on a much smaller scale than what we normally think of as small, and/or what they thought was possible at the time. It was at this time when curiosity for nanostructures had originated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[atomic force microscope]] (AFM) and the [[Scanning Tunneling Microscope]] (STM) are two early versions of scanning probes that launched nanotechnology. There are other types of [[scanning probe microscopy]], all flowing from the ideas of the scanning [[confocal microscope]] developed by [[Marvin Minsky]] in 1961 and the [[scanning acoustic microscope]] (SAM) developed by [[Calvin Quate]] and coworkers in the 1970s, that made it possible to see structures at the nanoscale. The tip of a scanning probe can also be used to manipulate nanostructures (a process called positional assembly). [[Feature-oriented_scanning|Feature-oriented scanning]]-[[Feature-oriented_positioning|positioning]] methodology suggested by Rostislav Lapshin appears to be a promising way to implement these nanomanipulations in automatic mode. However, this is still a slow process because of low scanning velocity of the microscope. Various techniques of [[nanolithography]] such as [[dip pen nanolithography]], [[electron beam lithography]] or [[nanoimprint lithography]] were also developed. Lithography is a top-down fabrication technique where a bulk material is reduced in size to nanoscale pattern. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The top-down approach anticipates nanodevices that must be built piece by piece in stages, much as manufactured items are currently made. [[Scanning probe microscopy]] is an important technique both for characterization and synthesis of nanomaterials. [[Atomic force microscope]]s and [[scanning tunneling microscope]]s can be used to look at surfaces and to move atoms around. By designing different tips for these microscopes, they can be used for carving out structures on surfaces and to help guide self-assembling structures. By using, for example, [[Feature-oriented_scanning|feature-oriented scanning]]-[[Feature-oriented_positioning|positioning]] approach, atoms can be moved around on a surface with scanning probe microscopy techniques. At present, it is expensive and time-consuming for mass production but very suitable for laboratory experimentation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In contrast, bottom-up techniques build or grow larger structures atom by atom or molecule by molecule. These techniques include [[chemical synthesis]], [[self-assembly]] and positional assembly. Another variation of the bottom-up approach is [[molecular beam epitaxy]] or MBE. Researchers at [[Bell Telephone Laboratories]] like John R. Arthur. Alfred Y. Cho, and Art C. Gossard developed and implemented MBE as a research tool in the late 1960s and 1970s. Samples made by MBE were key to the discovery of the fractional quantum Hall effect for which the [[1998]] [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] was awarded. MBE allows scientists to lay down atomically-precise layers of atoms and, in the process, build up complex structures. Important for research on semiconductors, MBE is also widely used to make samples and devices for the newly emerging field of [[spintronics]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Newer techniques such as [[Dual Polarisation Interferometry]] are enabling scientists to measure quantitatively the molecular interactions that take place at the nano-scale. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Applications == | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{main|List of nanotechnology applications}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although there has been much hype about the potential applications of nanotechnology, most current commercialized applications are limited to the use of "first generation" passive nanomaterials. These include titanium dioxide nanoparticles in sunscreen, cosmetics and some food products; silver nanoparticles in food packaging, clothing, disinfectants and household appliances; zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens and cosmetics, surface coatings, paints and outdoor furniture varnishes; and cerium oxide nanoparticles as a fuel catalyst. The Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars' Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies hosts an [http://www.nanotechproject.org/44 inventory of consumer products] which now contain nanomaterials. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However further applications which require actual manipulation or arrangement of nanoscale components await further research. Though technologies currently branded with the term 'nano' are sometimes little related to and fall far short of the most ambitious and transformative technological goals of the sort in molecular manufacturing proposals, the term still connotes such ideas. Thus there may be a danger that a "nano bubble" will form, or is forming already, from the use of the term by scientists and entrepreneurs to garner funding, regardless of interest in the transformative possibilities of more ambitious and far-sighted work. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The National Science Foundation (a major source of funding for nanotechnology in the United States) funded researcher David Berube to study the field of nanotechnology. His findings are published in the monograph “Nano-Hype: The Truth Behind the Nanotechnology Buzz". This published study (with a foreword by Mihail Roco, head of the NNI) concludes that much of what is sold as “nanotechnology” is in fact a recasting of straightforward materials science, which is leading to a “nanotech industry built solely on selling nanotubes, nanowires, and the like” which will “end up with a few suppliers selling low margin products in huge volumes." | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Implications == | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{main|Implications of nanotechnology}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Due to the far-ranging claims that have been made about potential applications of nanotechnology, a number of concerns have been raised about what effects these will have on our society if realized, and what action if any is appropriate to mitigate these risks. Short-term issues include the effects that widespread use of nanomaterials would have on human health and the environment. Longer-term concerns center on the implications that new technologies will have for society at large, and whether these could possibly lead to either a [[post scarcity]] economy, or alternatively exacerbate the wealth gap between developed and developing nations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Health and environmental issues === | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is a growing body of scientific evidence which demonstrates the potential for some [[nanomaterials]] to be [[toxic]] to humans or the environment [http://www.jnanobiotechnology.com/content/2/1/12], [http://www.ehponline.org/members/2005/7339/7339.html], [http://www.particleandfibretoxicology.com/content/2/1/8/]. The smaller a [[Nanoparticle|particle]], the greater its surface area to volume ratio and the higher its chemical reactivity and biological activity. The greater chemical reactivity of nanomaterials results in increased production of [[reactive oxygen species]] (ROS), including [[free radical]]s [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/311/5761/622]. ROS production has been found in a diverse range of nanomaterials including carbon [[fullerene]]s, [[carbon nanotube]]s and nanoparticle metal oxides. ROS and free radical production is one of the primary mechanisms of [[Nanotoxicity|nanoparticle toxicity]]; it may result in oxidative stress, inflammation, and consequent damage to proteins, membranes and DNA [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/311/5761/622]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The extremely small size of nanomaterials also means that they are much more readily taken up by the human body than larger sized particles. Nanomaterials are able to cross biological membranes and access [[Cell (biology)|cells]], tissues and organs that larger-sized particles normally cannot [http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/88/1/12]. Nanomaterials can gain access to the blood stream following inhalation [http://www.particleandfibretoxicology.com/content/2/1/8/] or ingestion [http://www.jnanobiotechnology.com/content/2/1/12]. At least some nanomaterials can penetrate the skin [http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/91/1/159]; even larger microparticles may penetrate skin when it is flexed [http://www.ehponline.org/docs/2003/5999/abstract.html]. Broken skin is an ineffective particle barrier [http://www.ehponline.org/members/2005/7339/7339.html], suggesting that acne, eczema, shaving wounds or severe sunburn may enable skin uptake of nanomaterials more readily. Once in the blood stream, nanomaterials can be transported around the body and are taken up by organs and tissues including the brain, heart, liver, kidneys, spleen, bone marrow and nervous system [http://www.ehponline.org/members/2005/7339/7339.html]. Nanomaterials have proved toxic to human tissue and cell cultures, resulting in increased [[oxidative stress]], inflammatory [[cytokine]] production and [[Necrosis|cell death]] [http://www.particleandfibretoxicology.com/content/2/1/8/]. Unlike larger particles, nanomaterials may be taken up by cell [[mitochondria]] [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1241427] and the [[cell nucleus]] [http://pubs3.acs.org/acs/journals/doilookup?in_doi=10.1021/es062541f], [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1310918]. Studies demonstrate the potential for nanomaterials to cause [[DNA]] [[mutation]] [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1310918] and induce major structural damage to mitochondria, even resulting in cell death [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1241427], [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/300/5619/615]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Size is therefore a key factor in determining the potential toxicity of a particle. However it is not the only important factor. Other properties of nanomaterials that influence toxicity include: chemical composition, shape, surface structure, surface charge, aggregation and solubility [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/311/5761/622], and the presence or absence of [[functional group]]s of other chemicals [http://pubs.acs.org/cgi-bin/abstract.cgi/nalefd/2006/6/i06/abs/nl060162e.html]. The large number of variables influencing toxicity means that it is difficult to generalise about health risks associated with exposure to nanomaterials – each new nanomaterial must be assessed individually and all material properties must be taken into account. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In its seminal 2004 report [http://www.nanotec.org.uk/finalReport.htm Nanoscience and Nanotechnologies: Opportunities and Uncertainties], the United Kingdom's Royal Society recommended that nanomaterials be regulated as new chemicals, that research laboratories and factories treat nanomaterials "as if they were [[Hazardous material|hazardous]]", that release of nanomaterials into the environment be avoided as far as possible, and that products containing nanomaterials be subject to new safety testing requirements prior to their commercial release. Yet regulations world-wide still fail to distinguish between materials in their nanoscale and bulk form. This means that nanomaterials remain effectively unregulated; there is no regulatory requirement for nanomaterials to face new health and safety testing or environmental impact assessment prior to their use in commercial products, if these materials have already been approved in bulk form. | ||

| − | + | The health risks of nanomaterials are of particular concern for workers who may face [[Occupational safety and health|occupational exposure]] to nanomaterials at higher levels, and on a more routine basis, than the general public. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | === Broader societal implications and challenges === |

| − | = | + | Beyond the toxicity risks to human health and the environment which are associated with first-generation nanomaterials, nanotechnology has broader societal implications and poses broader social challenges. Social scientists have suggested that nanotechnology's social issues should be understood and assessed not simply as "downstream" risks or impacts, but as challenges to be factored into "upstream" research and decision making, in order to ensure technology development that meets social objectives [http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content?content=10.1080/09505430601022619]. Many social scientists and civil society organisations further suggest that [[technology assessment]] and governance should also involve public participation [http://csec.lancs.ac.uk/docs/nano%20project%20sci%20com%20proofs%20nov05.pdf], [http://www.nanolabweb.com/index.cfm/action/main.default.viewArticle/articleID/135/CFID/60255/CFTOKEN/45212442/], [http://www.wmin.ac.uk/sshl/pdf/CSDBUlletinMohr.pdf], [http://www.demos.co.uk/publications/governingatthenanoscale]. |

| − | |||

| − | + | Some observers suggest that nanotechnology will build incrementally, as did the 18-19th century [[industrial revolution]], until it gathers pace to drive a nanotechnological revolution that will radically reshape our economies, our labour markets, international trade, international relations, social structures, civil liberties, our relationship with the natural world and even what we understand to be human. Others suggest that it may be more accurate to describe nanotechnology-driven changes as a “technological [[tsunami]]”. Just like a tsunami, analysts warn that rapid nanotechnology-driven change will necessarily have profound disruptive impacts. As the APEC Center for Technology Foresight observes: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

| − | + | If nanotechnology is going to revolutionise manufacturing, health care, energy supply, communications and probably defence, then it will transform labour and the workplace, the medical system, the transportation and power infrastructures and the military. None of these latter will be changed without significant social disruption. [http://www.apecforesight.org/php/publication/download1.php?pub_id=5 | |

| − | + | </blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The implications of the analysis of such a powerful new technology remain sharply divided. Nano optimists, including many governments, see nanotechnology delivering environmentally benign material abundance for all by providing universal clean water supplies; atomically engineered food and crops resulting in greater agricultural productivity with less labour requirements; nutritionally enhanced interactive ‘smart’ foods; cheap and powerful [[energy]] generation; clean and highly efficient manufacturing; radically improved formulation of [[drug]]s, diagnostics and organ replacement; much greater [[Information technology|information storage and communication]] capacities; interactive ‘smart’ appliances; and increased human performance through convergent technologies [http://www.ostp.gov/NSTC/html/iwgn/iwgn.fy01budsuppl/nni.pdf], [http://cordis.europa.eu/nanotechnology/actionplan.htm]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | = | + | Nano skeptics suggest that nanotechnology will simply exacerbate problems stemming from existing socio-economic inequity and the unequal distribution of power by creating greater inequities between rich and poor through an inevitable nano-divide (the gap between those who control the new nanotechnologies and those whose products, services or labour are displaced by them); destabilising international relations through a growing nano arms race and increased potential for [[bioweapon]]ry; providing the tools for ubiquitous surveillance, with significant implications for [[civil liberty]]; breaking down the barriers between life and non-life through [[nanobiotechnology]], and redefining even what it means to be human [http://www.etcgroup.org/en/materials/publications.html?pub_id=104], [http://nano.foe.org.au/node/168]. |

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | + | == See also == | |

| − | * [ | + | * [[List of nanotechnology topics]] |

| + | * [[Nanoengineering]] | ||

| + | * [[Nanotechnology in fiction]] | ||

| + | * [[Top-down and bottom-up design]] | ||

| + | * [[Nanotechnology education]] | ||

| + | * [[List of nanotechnology organizations]] | ||

| + | * [[Energy Applications of Nanotechnology]] | ||

| + | * [[Grinding and Dispersing Nanoparticles]] | ||

| − | * [http:// | + | == Further reading == |

| + | * [http://lifeboat.com/ex/bios.geoffrey.p.hunt Geoffrey Hunt] and [http://lifeboat.com/ex/bios.michael.d.mehta Michael Mehta] (2006), Nanotechnology: Risk, Ethics and Law. London: Earthscan Books. | ||

| + | * Hari Singh Nalwa (2004), Encyclopedia of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (10-Volume Set), American Scientific Publishers. ISBN 1-58883-001-2 | ||

| + | * Michael Rieth and Wolfram Schommers (2006), Handbook of Theoretical and Computational Nanotechnology (10-Volume Set), American Scientific Publishers. ISBN 1-58883-042-X | ||

| + | * Yuliang Zhao and Hari Singh Nalwa (2007), Nanotoxicology, American Scientific Publishers. ISBN 1-58883-088-8 | ||

| + | * Hari Singh Nalwa and Thomas Webster (2007), Cancer Nanotechnology, American Scientific Publishers. ISBN 1-58883-071-3 | ||

| + | <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | ||

| + | * [http://lifeboat.com/ex/bios.david.m.berube David M. Berube] 2006. ''Nano-hype: The Truth Behind the Nanotechnology Buzz''. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-351-3 | ||

| + | * {{cite book|author=Jones, Richard A. L.|title=Soft Machines|publisher=Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom|year=2004|id=ISBN 0198528558}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book|author=Akhlesh Lakhtakia (ed)|title=The Handbook of Nanotechnology. Nanometer Structures: Theory, Modeling, and Simulation|year=2004| | ||

| + | publisher=SPIE Press, Bellingham, WA, USA|id=ISBN 0-8194-5186-X}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book|author=Daniel J. Shanefield|year=1996|title=Organic Additives And Ceramic Processing|publisher=Kluwer Academic Publishers|id=ISBN 0-7923-9765-7}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book|author=Fei Wang & Akhlesh Lakhtakia (eds)|title=Selected Papers on Nanotechnology — Theory & Modeling (Milestone Volume 182)| | ||

| + | publisher=SPIE Press, Bellingham, WA, USA|year=2006|id=ISBN 0-8194-6354-X}} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | * Roger Smith, ''Nanotechnology: A Brief Technology Analysis'', CTOnet.org, 2004. [http://www.ctonet.org/documents/Nanotech_analysis.pdf] | ||

| + | * Arius Tolstoshev, ''Nanotechnology: Assessing the Environmental Risks for Australia'', Earth Policy Centre, September 2006. [http://www.earthpolicy.org.au/nanotech.pdf] | ||

| + | * Hunt, G & Mehta, M (eds) ''Nanotechnology: Risk, Ethics & Law''. Earthscan, London 2006. | ||

| + | * Friends of the Earth, "Nanotechnology, sunscreens and cosmetics: Small ingredients, big risks", 2006. [http://nano.foe.org.au/node/125] | ||

| − | + | == External links == | |

| − | + | :''For external links to companies and institutions involved in nanotechnology, please see [[List of nanotechnology organizations]].'' | |

| + | {{Commons}} | ||

| + | {{WVD}} | ||

| + | <!--===========================({{NoMoreLinks}})===============================—> | ||

| + | <!--| DO NOT ADD MORE LINKS TO THIS ARTICLE. WIKIPEDIA IS NOT A COLLECTION OF |—> | ||

| + | <!--| LINKS. If you think that your link might be useful, do not add it here, |—> | ||

| + | <!--| but put it on this article's discussion page first or submit your link |—> | ||

| + | <!--| to the appropriate category at the Open Directory Project (www.dmoz.org)|—> | ||

| + | <!--| and link back to that category using the {{dmoz}} template. |—> | ||

| + | <!--| |—> | ||

| + | <!--| Links that have not been verified WILL BE DELETED. |—> | ||

| + | <!--| See [[Wikipedia:External links]] and [[Wikipedia:Spam]] for details |—> | ||

| + | <!--===========================({{NoMoreLinks}})===============================—> | ||

| + | <!-- —> | ||

| + | <!-- If you are adding a link to an individual institution or company, please add —> | ||

| + | <!-- an entry to "List of nanotechnology organizations" instead of here. Thanks! —> | ||

| + | * {{dmoz|Science/Technology/Nanotechnology/|Nanotechnology}} | ||

| + | * [http://org.ntnu.no/nanowiki/mwiki/index.php/Main_Page Nanotechnology NanoWiki - The nanotechology page of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology] | ||

| + | * [http://www.nanotech-now.com Nanotechnology Now] - News and information source on everything nano | ||

| + | * [http://nanotechnology.com Nanotechnology.com] | ||

| + | * [http://www.smalltimes.com Small Times] - Nanotechnology News & Resources | ||

| + | * [http://www.nanohub.org/ nanoHUB] - Online Nanotechnology resource with simulation programs, seminars and lectures | ||

| + | * [http://www.nanomaterialdatabase.org Nanowerk Nanotechnology Portal] | ||

| + | * [http://www.nanoforum.org/ European Nanoforum] | ||

| + | * [http://nanoed.org/ NanoEd Resource Portal] - Repository of courses, concepts, simulations, professional development programs, seminars, etc. | ||

| + | * [http://nclt.us/ National Center for Learning and Teaching in Nanoscale Science and Engineering (NCLT)] | ||

| + | * [http://www.nanohive-1.org/atHome/ NanoHive@Home] - Distributed Computing Project | ||

| + | * [http://www.aacr.org/home/public—media/for-the-media/fact-sheets/cancer-concepts/nanotechnology.aspx American Association for Cancer Research: Nanotechnology] | ||

| + | * [http://www.cheresources.com/nanotech1.shtml Capitalizing on Nanotechnolgy's Enormous Promise] - Article from CheResources.com | ||

| + | * [http://rarecor.com/ RARE Corporation] Nanotechnology professional development short courses | ||

| + | * [http://www.mec.cf.ac.uk/services/?view=nano_technology&style=default Manufacturing Engineering Centre (MEC), Cardiff University, UK.] | ||

| + | * [http://www.wilsoncenter.org/index.cfm?topic_id=116811&fuseaction=topics.event_summary&event_id=216016 VIDEO: Using Nanotechnology to Improve Health in Developing Countries] February 27, 2007 at the Woodrow Wilson Center | ||

| + | * [http://www.bioforcenano.com BioForce Nanosciences, Inc.]- New nanotechnology concepts in the life sciences. | ||

| + | * [http://www.nanolab.ucla.edu/ UCLA Nanoelectronics Research Facility] | ||

| + | * [http://www.cnsi.ucla.edu/ California Nanosystems Institute at UCLA] | ||

{{Technology}} | {{Technology}} | ||

<!--Categories—> | <!--Categories—> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Nanotechnology| ]] | [[Category:Nanotechnology| ]] | ||

<!--Interwiki—> | <!--Interwiki—> | ||

| − | + | [[ar:تقانة نانوية]] | |

| + | [[bn:ন্যানোপ্রযুক্তি]] | ||

| + | [[zh-min-nan:Nano ki-su̍t]] | ||

| + | [[cs:Nanotechnologie]] | ||

| + | [[da:Nanoteknologi]] | ||

| + | [[de:Nanotechnologie]] | ||

| + | [[et:Nanotehnoloogia]] | ||

| + | [[el:Νανοτεχνολογία]] | ||

| + | [[es:Nanotecnología]] | ||

| + | [[eo:Nanoteknologio]] | ||

| + | [[fa:فناوری نانو]] | ||

| + | [[fr:Nanotechnologie]] | ||

| + | [[gl:Nanotecnoloxía]] | ||

| + | [[ko:나노 과학]] | ||

| + | [[hi:नैनोतकनीकी]] | ||

| + | [[id:Nanoteknologi]] | ||

| + | [[it:Nanotecnologia]] | ||

| + | [[he:ננוטכנולוגיה]] | ||

| + | [[lt:Nanotechnologija]] | ||

| + | [[hu:Nanotechnológia]] | ||

| + | [[ml:നാനോ ടെക്നോളജി]] | ||

| + | [[ms:Nanoteknologi]] | ||

| + | [[nl:Nanotechnologie]] | ||

| + | [[ja:ナノテクノロジー]] | ||

| + | [[no:Nanoteknologi]] | ||

| + | [[nn:Nanoteknologi]] | ||

| + | [[pl:Nanotechnologia]] | ||

| + | [[pt:Nanotecnologia]] | ||

| + | [[ro:Nanotehnologie]] | ||

| + | [[ru:Нанотехнология]] | ||

| + | [[sq:Nanoteknologjia]] | ||

| + | [[sk:Nanotechnológia]] | ||

| + | [[sl:Nanotehnologija]] | ||

| + | [[sr:Нанотехнологија]] | ||

| + | [[su:Nanotéhnologi]] | ||

| + | [[fi:Nanoteknologia]] | ||

| + | [[sv:Nanoteknik]] | ||

| + | [[ta:நனோ தொழில்நுட்பம்]] | ||

| + | [[th:นาโนเทคโนโลยี]] | ||

| + | [[vi:Công nghệ nano]] | ||

| + | [[tr:Nanoteknoloji]] | ||

| + | [[uk:Нанотехнології]] | ||

| + | [[ur:قزمہ طرزیات]] | ||

| + | [[diq:Nanoteknolociye]] | ||

| + | [[zh:纳米科技]] | ||

Revision as of 21:27, 26 June 2007

- "Nanotech" redirects here.

Nanotechnology is a field of applied science and technology covering a broad range of topics. The main unifying theme is the control of matter on a scale smaller than 1 micrometre, normally between 1-100 nanometers, as well as the fabrication of devices on this same length scale. It is a highly multidisciplinary field, drawing from fields such as colloidal science, device physics, and supramolecular chemistry. Much speculation exists as to what new science and technology might result from these lines of research. Some view nanotechnology as a marketing term that describes pre-existing lines of research applied to the sub-micron size scale.

Despite the apparent simplicity of this definition, nanotechnology actually encompasses diverse lines of inquiry. Nanotechnology cuts across many disciplines, including colloidal science, chemistry, applied physics, materials science, and even mechanical and electrical engineering. It could variously be seen as an extension of existing sciences into the nanoscale, or as a recasting of existing sciences using a newer, more modern term. Two main approaches are used in nanotechnology: one is a "bottom-up" approach where materials and devices are built from molecular components which assemble themselves chemically using principles of molecular recognition; the other being a "top-down" approach where nano-objects are constructed from larger entities without atomic-level control.

The impetus for nanotechnology has stemmed from a renewed interest in colloidal science, coupled with a new generation of analytical tools such as the atomic force microscope (AFM), and the scanning tunneling microscope (STM). Combined with refined processes such as electron beam lithography and molecular beam epitaxy, these instruments allow the deliberate manipulation of nanostructures, and in turn led to the observation of novel phenomena. The manufacture of polymers based on molecular structure, or the design of computer chip layouts based on surface science are examples of nanotechnology in modern use. Despite the great promise of numerous nanotechnologies such as quantum dots and nanotubes, real applications that have moved out of the lab and into the marketplace have mainly utilized the advantages of colloidal nanoparticles in bulk form, such as suntan lotion, cosmetics, protective coatings, and stain resistant clothing.

| Topics | |

|---|---|

| History · Implications Applications · Organizations Popular culture · List of topics | |

| Subfields and related fields | |

| Nanomedicine Molecular self-assembly Molecular electronics Scanning probe microscopy Nanolithography Molecular nanotechnology | |

| Nanomaterials | |

| Nanomaterials · Fullerene Carbon nanotubes Fullerene chemistry Applications · Popular culture Timeline · Carbon allotropes Nanoparticles · Quantum dots Colloidal gold · Colloidal silver | |

| Molecular nanotechnology | |

| Molecular assembler Mechanosynthesis Nanorobotics · Grey goo K. Eric Drexler Engines of Creation | |

Origins

The first distinguishing concepts in nanotechnology (but predating use of that name) was in "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom," a talk given by physicist Richard Feynman at an American Physical Society meeting at Caltech on December 29, 1959. Feynman described a process by which the ability to manipulate individual atoms and molecules might be developed, using one set of precise tools to build and operate another proportionally smaller set, so on down to the needed scale. In the course of this, he noted, scaling issues would arise from the changing magnitude of various physical phenomena: gravity would become less important, surface tension and Van der Waals attraction would become more important, etc. This basic idea appears feasible, and exponential assembly enhances it with parallelism to produce a useful quantity of end products.

The term "nanotechnology" was defined by Tokyo Science University Professor Norio Taniguchi in a 1974 paper (N. Taniguchi, "On the Basic Concept of 'Nano-Technology'," Proc. Intl. Conf. Prod. Eng. Tokyo, Part II, Japan Society of Precision Engineering, 1974.) as follows: "'Nano-technology' mainly consists of the processing of, separation, consolidation, and deformation of materials by one atom or by one molecule." In the 1980s the basic idea of this definition was explored in much more depth by Dr. K. Eric Drexler, who promoted the technological significance of nano-scale phenomena and devices through speeches and the books Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology (1986) and Nanosystems: Molecular Machinery, Manufacturing, and Computation, (1998, ISBN 0-471-57518-6), and so the term acquired its current sense.

Nanotechnology and nanoscience got started in the early 1980s with two major developments; the birth of cluster science and the invention of the scanning tunneling microscope (STM). This development led to the discovery of fullerenes in 1986 and carbon nanotubes a few years later. In another development, the synthesis and properties of semiconductor nanocrystals was studied. This led to a fast increasing number of metal oxide nanoparticles of quantum dots. The atomic force microscope was invented five years after the STM was invented. The AFM uses atomic force to see the atoms.

Fundamental concepts

One nanometer (nm) is one billionth, or 10-9 of a meter. For comparison, typical carbon-carbon bond lengths, or the spacing between these atoms in a molecule, are in the range .12-.15 nm, and a DNA double-helix has a diameter around 2 nm. On the other hand, the smallest cellular lifeforms, the bacteria of the genus Mycoplasma, are around 200 nm in length.

Larger to smaller: a materials perspective

A unique aspect of nanotechnology is the vastly increased ratio of surface area to volume present in many nanoscale materials which opens new possibilities in surface-based science, such as catalysis. A number of physical phenomena become noticeably pronounced as the size of the system decreases. These include statistical mechanical effects, as well as quantum mechanical effects, for example the “quantum size effect” where the electronic properties of solids are altered with great reductions in particle size. This effect does not come into play by going from macro to micro dimensions. However, it becomes dominant when the nanometer size range is reached. Additionally, a number of physical properties change when compared to macroscopic systems. One example is the increase in surface area to volume of materials. This catalytic activity also opens potential risks in their interaction with biomaterials.

Materials reduced to the nanoscale can suddenly show very different properties compared to what they exhibit on a macroscale, enabling unique applications. For instance, opaque substances become transparent (copper); inert materials become catalysts (platinum); stable materials turn combustible (aluminum); solids turn into liquids at room temperature (gold); insulators become conductors (silicon). A material such as gold, which is chemically inert at normal scales, can serve as a potent chemical catalyst at nanoscales. Much of the fascination with nanotechnology stems from these unique quantum and surface phenomena that matter exhibits at the nanoscale.

Simple to complex: a molecular perspective

Modern synthetic chemistry has reached the point where it is possible to prepare small molecules to almost any structure. These methods are used today to produce a wide variety of useful chemicals such as pharmaceuticals or commercial polymers. This ability raises the question of extending this kind of control to the next-larger level, seeking methods to assemble these single molecules into supramolecular assemblies consisting of many molecules arranged in a well defined manner.

These approaches utilize the concepts of molecular self-assembly and/or supramolecular chemistry to automatically arrange themselves into some useful conformation through a bottom-up approach. The concept of molecular recognition is especially important: molecules can be designed so that a specific conformation or arrangement is favored due to non-covalent intermolecular forces. The Watson-Crick basepairing rules are a direct result of this, as is the specificity of an enzyme being targeted to a single substrate, or the specific folding of the protein itself. Thus, two or more components can be designed to be complementary and mutually attractive so that they make a more complex and useful whole.

Such bottom-up approaches should, broadly speaking, be able to produce devices in parallel and much cheaper than top-down methods, but could potentially be overwhelmed as the size and complexity of the desired assembly increases. Most useful structures require complex and thermodynamically unlikely arrangements of atoms. Nevertheless, there are many examples of self-assembly based on molecular recognition in biology, most notably Watson-Crick basepairing and enzyme-substrate interactions. The challenge for nanotechnology is whether these principles can be used to engineer novel constructs in addition to natural ones.

Molecular nanotechnology: a long-term view

Molecular nanotechnology, sometimes called molecular manufacturing, is a term given to the concept of engineered nanosystems (nanoscale machines) operating on the molecular scale. It is especially associated with the concept of a molecular assembler, a machine that can produce a desired structure or device atom-by-atom using the principles of mechanosynthesis. Manufacturing in the context of productive nanosystems is not related to, and should be clearly distinguished from, the conventional technologies used to manufacture nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes and nanoparticles.

When the term "nanotechnology" was independently coined and popularized by Eric Drexler (who at the time was unaware of an earlier usage by Norio Taniguchi) it referred to a future manufacturing technology based on molecular machine systems. The premise was that molecular-scale biological analogies of traditional machine components demonstrated molecular machines were possible: by the countless examples found in biology, it is known that billions of years of evolutionary feedback can produce sophisticated, stochastically optimised biological machines. It is hoped that developments in nanotechnology will make possible their construction by some other means, perhaps using biomimetic principles. However, Drexler and other researchers have proposed that advanced nanotechnology, although perhaps initially implemented by biomimetic means, ultimately could be based on mechanical engineering principles, namely, a manufacturing technology based on the mechanical functionality of these components (such as gears, bearings, motors, and structural members) that would enable programmable, positional assembly to atomic specification (PNAS-1981). The physics and engineering performance of exemplar designs were analyzed in Drexler's book Nanosystems. But Drexler's analysis is very qualitative and does not address very pressing issues, such as the "fat fingers" and "Sticky fingers" problems. In general it is very difficult to assemble devices on the atomic scale, as all one has to position atoms are other atoms of comparable size and stickyness.

Another view, put forth by Carlo Montemagno, is that future nanosystems will be hybrids of silicon technology and biological molecular machines. Yet another view, put forward by the late Richard Smalley, is that mechanosynthesis is impossible due to the difficulties in mechanically manipulating individual molecules. This led to an exchange of letters in the ACS publication Chemical & Engineering News in 2003.

Though biology clearly demonstrates that molecular machine systems are possible, non-biological molecular machines are today only in their infancy. Leaders in research on non-biological molecular machines are Dr. Alex Zettl and his colleagues at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories and UC Berkeley. They have constructed at least three distinct molecular devices whose motion is controlled from the desktop with changing voltage: a nanotube nanomotor, a molecular actuator, and a nanoelectromechanical relaxation oscillator. An experiment indicating that positional molecular assembly is possible was performed by Ho and Lee at Cornell University in 1999. They used a scanning tunneling microscope to move an individual carbon monoxide molecule (CO) to an individual iron atom (Fe) sitting on a flat silver crystal, and chemically bound the CO to the Fe by applying a voltage.

Current research

As nanotechnology is a very broad term, there are many disparate but sometimes overlapping subfields that could fall under its umbrella. The following avenues of research could be considered subfields of nanotechnology. Note that these categories are fairly nebulous and a single subfield may overlap many of them, especially as the field of nanotechnology continues to mature.

Nanomaterials

This includes subfields which develop or study materials having unique properties arising from their nanoscale dimensions.

- Colloid science has given rise to many materials which may be useful in nanotechnology, such as carbon nanotubes and other fullerenes, and various nanoparticles and nanorods.

- Nanoscale materials can also be used for bulk applications; most present commercial applications of nanotechnology are of this flavor.

- Progress has been made in using these materials for medical applications; see Nanomedicine.

Bottom-up approaches

These seek to arrange smaller components into more complex assemblies.

- DNA Nanotechnology utilises the specificity of Watson-Crick basepairing to construct well-defined structures out of DNA and other nucleic acids.

- More generally, molecular self-assembly seeks to use concepts of supramolecular chemistry, and molecular recognition in particular, to cause single-molecule components to automatically arrange themselves into some useful conformation.

Top-down approaches

These seek to create smaller devices by using larger ones to direct their assembly.

- Many technologies descended from conventional solid-state silicon methods for fabricating microprocessors are now capable of creating features smaller than 100 nm, falling under the definition of nanotechnology. Giant magnetoresistance-based hard drives already on the market fit this description, [2] as do atomic layer deposition (ALD) techniques.

- Solid-state techniques can also be used to create devices known as nanoelectromechanical systems or NEMS, which are related to microelectromechanical systems or MEMS.

- Atomic force microscope tips can be used as a nanoscale "write head" to deposit a chemical on a surface in a desired pattern in a process called dip pen nanolithography. This fits into the larger subfield of nanolithography.

Functional approaches

These seek to develop components of a desired functionality without regard to how they might be assembled.

- Molecular electronics seeks to develop molecules with useful electronic properties. These could then be used as single-molecule components in a nanoelectronic device. For an example see rotaxane.

- Synthetic chemical methods can also be used to create synthetic molecular motors, such as in a so-called nanocar.

Speculative

These subfields seek to anticipate what inventions nanotechnology might yield, or attempt to propose an agenda along which inquiry might progress. These often take a big-picture view of nanotechnology, with more emphasis on its societal implications than the details of how such inventions could actually be created.

- Molecular nanotechnology is a proposed approach which involves manipulating single molecules in finely controlled, deterministic ways. This is more theoretical than the other subfields and is beyond current capabilities.

- Nanorobotics centers on self-sufficient machines of some functionality operating at the nanoscale. There are hopes for applying nanorobots in medicine [1][2][3], while it might not be easy to do such a thing because of several drawbacks of such devices [4][5]. Nevertheless, progress on innovative materials and methodologies has been demonstrated with some patents granted about new nanomanufacturing devices for future commercial applications, which also progressively helps in the development towards nanorobots with the use of embedded nanobioelectronics concept[6].

- Programmable matter based on artificial atoms seeks to design materials whose properties can be easily and reversibly externally controlled.

- Due to the popularity and media exposure of the term nanotechnology, the words picotechnology and femtotechnology have been coined in analogy to it, although these are only used rarely and informally.

Tools and techniques

Another technique uses SPT™s (surface patterning tool) as the molecular “ink cartridge”. Each SPT is a microcantilever-based micro-fluidic handling device. SPTs contain either a single microcantilever print head or multiple microcantilevers for simultaneous printing of multiple molecular species. The integrated microfluidic network transports fluid samples from reservoirs located on the SPT through microchannels to the distal end of the cantilever. Thus SPTs can be used to print materials that include biological samples such as proteins, DNA, RNA, and whole viruses, as well as non-biological samples such as chemical solutions, colloids and particle suspensions. SPTs are most commonly used with molecular printers.

Nanotechnological techniques include those used for fabrication of nanowires, those used in semiconductor fabrication such as deep ultraviolet lithography, electron beam lithography, focused ion beam machining, nanoimprint lithography, atomic layer deposition, and molecular vapor deposition, and further including molecular self-assembly techniques such as those employing di-block copolymers. However, all of these techniques preceded the nanotech era, and are extensions in the development of scientific advancements rather than techniques which were devised with the sole purpose of creating nanotechnology and which were results of nanotechnology research.

Nanoscience and nanotechnology only became possible in the 1910s with the development of the first tools to measure and make nanostructures. But the actual development started with the discovery of electrons and neutrons which showed scientists that matter can really exist on a much smaller scale than what we normally think of as small, and/or what they thought was possible at the time. It was at this time when curiosity for nanostructures had originated.

The atomic force microscope (AFM) and the Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM) are two early versions of scanning probes that launched nanotechnology. There are other types of scanning probe microscopy, all flowing from the ideas of the scanning confocal microscope developed by Marvin Minsky in 1961 and the scanning acoustic microscope (SAM) developed by Calvin Quate and coworkers in the 1970s, that made it possible to see structures at the nanoscale. The tip of a scanning probe can also be used to manipulate nanostructures (a process called positional assembly). Feature-oriented scanning-positioning methodology suggested by Rostislav Lapshin appears to be a promising way to implement these nanomanipulations in automatic mode. However, this is still a slow process because of low scanning velocity of the microscope. Various techniques of nanolithography such as dip pen nanolithography, electron beam lithography or nanoimprint lithography were also developed. Lithography is a top-down fabrication technique where a bulk material is reduced in size to nanoscale pattern.

The top-down approach anticipates nanodevices that must be built piece by piece in stages, much as manufactured items are currently made. Scanning probe microscopy is an important technique both for characterization and synthesis of nanomaterials. Atomic force microscopes and scanning tunneling microscopes can be used to look at surfaces and to move atoms around. By designing different tips for these microscopes, they can be used for carving out structures on surfaces and to help guide self-assembling structures. By using, for example, feature-oriented scanning-positioning approach, atoms can be moved around on a surface with scanning probe microscopy techniques. At present, it is expensive and time-consuming for mass production but very suitable for laboratory experimentation.

In contrast, bottom-up techniques build or grow larger structures atom by atom or molecule by molecule. These techniques include chemical synthesis, self-assembly and positional assembly. Another variation of the bottom-up approach is molecular beam epitaxy or MBE. Researchers at Bell Telephone Laboratories like John R. Arthur. Alfred Y. Cho, and Art C. Gossard developed and implemented MBE as a research tool in the late 1960s and 1970s. Samples made by MBE were key to the discovery of the fractional quantum Hall effect for which the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded. MBE allows scientists to lay down atomically-precise layers of atoms and, in the process, build up complex structures. Important for research on semiconductors, MBE is also widely used to make samples and devices for the newly emerging field of spintronics.

Newer techniques such as Dual Polarisation Interferometry are enabling scientists to measure quantitatively the molecular interactions that take place at the nano-scale.

Applications

Although there has been much hype about the potential applications of nanotechnology, most current commercialized applications are limited to the use of "first generation" passive nanomaterials. These include titanium dioxide nanoparticles in sunscreen, cosmetics and some food products; silver nanoparticles in food packaging, clothing, disinfectants and household appliances; zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens and cosmetics, surface coatings, paints and outdoor furniture varnishes; and cerium oxide nanoparticles as a fuel catalyst. The Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars' Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies hosts an inventory of consumer products which now contain nanomaterials.

However further applications which require actual manipulation or arrangement of nanoscale components await further research. Though technologies currently branded with the term 'nano' are sometimes little related to and fall far short of the most ambitious and transformative technological goals of the sort in molecular manufacturing proposals, the term still connotes such ideas. Thus there may be a danger that a "nano bubble" will form, or is forming already, from the use of the term by scientists and entrepreneurs to garner funding, regardless of interest in the transformative possibilities of more ambitious and far-sighted work.

The National Science Foundation (a major source of funding for nanotechnology in the United States) funded researcher David Berube to study the field of nanotechnology. His findings are published in the monograph “Nano-Hype: The Truth Behind the Nanotechnology Buzz". This published study (with a foreword by Mihail Roco, head of the NNI) concludes that much of what is sold as “nanotechnology” is in fact a recasting of straightforward materials science, which is leading to a “nanotech industry built solely on selling nanotubes, nanowires, and the like” which will “end up with a few suppliers selling low margin products in huge volumes."

Implications

Due to the far-ranging claims that have been made about potential applications of nanotechnology, a number of concerns have been raised about what effects these will have on our society if realized, and what action if any is appropriate to mitigate these risks. Short-term issues include the effects that widespread use of nanomaterials would have on human health and the environment. Longer-term concerns center on the implications that new technologies will have for society at large, and whether these could possibly lead to either a post scarcity economy, or alternatively exacerbate the wealth gap between developed and developing nations.

Health and environmental issues

There is a growing body of scientific evidence which demonstrates the potential for some nanomaterials to be toxic to humans or the environment [3], [4], [5]. The smaller a particle, the greater its surface area to volume ratio and the higher its chemical reactivity and biological activity. The greater chemical reactivity of nanomaterials results in increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including free radicals [6]. ROS production has been found in a diverse range of nanomaterials including carbon fullerenes, carbon nanotubes and nanoparticle metal oxides. ROS and free radical production is one of the primary mechanisms of nanoparticle toxicity; it may result in oxidative stress, inflammation, and consequent damage to proteins, membranes and DNA [7].

The extremely small size of nanomaterials also means that they are much more readily taken up by the human body than larger sized particles. Nanomaterials are able to cross biological membranes and access cells, tissues and organs that larger-sized particles normally cannot [8]. Nanomaterials can gain access to the blood stream following inhalation [9] or ingestion [10]. At least some nanomaterials can penetrate the skin [11]; even larger microparticles may penetrate skin when it is flexed [12]. Broken skin is an ineffective particle barrier [13], suggesting that acne, eczema, shaving wounds or severe sunburn may enable skin uptake of nanomaterials more readily. Once in the blood stream, nanomaterials can be transported around the body and are taken up by organs and tissues including the brain, heart, liver, kidneys, spleen, bone marrow and nervous system [14]. Nanomaterials have proved toxic to human tissue and cell cultures, resulting in increased oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokine production and cell death [15]. Unlike larger particles, nanomaterials may be taken up by cell mitochondria [16] and the cell nucleus [17], [18]. Studies demonstrate the potential for nanomaterials to cause DNA mutation [19] and induce major structural damage to mitochondria, even resulting in cell death [20], [21].

Size is therefore a key factor in determining the potential toxicity of a particle. However it is not the only important factor. Other properties of nanomaterials that influence toxicity include: chemical composition, shape, surface structure, surface charge, aggregation and solubility [22], and the presence or absence of functional groups of other chemicals [23]. The large number of variables influencing toxicity means that it is difficult to generalise about health risks associated with exposure to nanomaterials – each new nanomaterial must be assessed individually and all material properties must be taken into account.

In its seminal 2004 report Nanoscience and Nanotechnologies: Opportunities and Uncertainties, the United Kingdom's Royal Society recommended that nanomaterials be regulated as new chemicals, that research laboratories and factories treat nanomaterials "as if they were hazardous", that release of nanomaterials into the environment be avoided as far as possible, and that products containing nanomaterials be subject to new safety testing requirements prior to their commercial release. Yet regulations world-wide still fail to distinguish between materials in their nanoscale and bulk form. This means that nanomaterials remain effectively unregulated; there is no regulatory requirement for nanomaterials to face new health and safety testing or environmental impact assessment prior to their use in commercial products, if these materials have already been approved in bulk form.

The health risks of nanomaterials are of particular concern for workers who may face occupational exposure to nanomaterials at higher levels, and on a more routine basis, than the general public.

Broader societal implications and challenges

Beyond the toxicity risks to human health and the environment which are associated with first-generation nanomaterials, nanotechnology has broader societal implications and poses broader social challenges. Social scientists have suggested that nanotechnology's social issues should be understood and assessed not simply as "downstream" risks or impacts, but as challenges to be factored into "upstream" research and decision making, in order to ensure technology development that meets social objectives [24]. Many social scientists and civil society organisations further suggest that technology assessment and governance should also involve public participation [25], [26], [27], [28].