Difference between revisions of "Genghis Khan" - New World Encyclopedia

(import, credit, category) |

(→Attacks on Georgia and Volga Bulgaria: image editing) |

||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

===Attacks on Georgia and Volga Bulgaria=== | ===Attacks on Georgia and Volga Bulgaria=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Geor_tamro.gif|thumb|200px|right|Georgia at the eve of reconaissance by Subutai and Jebe generals]] | + | [[Image:Geor_tamro.gif|thumb|200px|right|Georgia at the eve of reconaissance by Subutai and Jebe generals. Copyright©2004 Andrew Andersen. Source: Atlas of Conflicts]] |

{{main|Mongol invasions of Georgia}} | {{main|Mongol invasions of Georgia}} | ||

{{main|Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria}} | {{main|Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria}} | ||

Revision as of 23:28, 13 July 2006

- This page is about the emperor. For other uses, see the disambiguation pages for Genghis Khan.

| |

| Birth name: | Temüjin Borjigin |

| Family name: | Borjigin |

| Title: | Khagan of Mongol Empire |

| Birth: | c. 1162 |

| Place of birth: | Hentiy, Mongolia |

| Death: | August 18, 1227 |

| Dates of reign: | 1206 –August 18, 1227 |

| Succeeded by: | Ögedei Khan |

| Marriage: | Börte Ujin, Kulan, Yisugen, Yisui, many others |

| Children: |

|

| Note: * Conferred posthumously | |

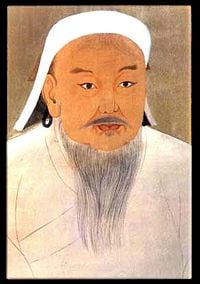

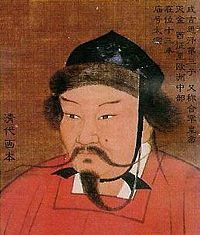

Genghis Khan ▶, (c. 1162[1]–August 18, 1227) (IPA: [ʧiŋgɪs χaːŋ], Mongolian: Чингис Хаан, Chinese: 成吉思汗, Turkic: Chengez Khan or Chinggis Khan, Chingis Khan, Jenghis Khan, Chinggis Qan, etc.), was a Mongol political and military leader who founded the Mongol Empire (Их Монгол Улс), (1206–1368), the largest contiguous empire in world history. Born Temüjin (Mongolian: Тэмүүжин, Traditional Chinese: 鐵木真; pinyin: Tiěmùzhēn), he united the Mongol tribes and forged a powerful army based on meritocracy, to become one of the most successful military leaders in history.

While his image in most of the world is that of a ruthless bloodthirsty conqueror, Genghis Khan is celebrated as a hero in Mongolia, where he is seen as the father of the Mongol Nation. Before becoming a Khan, Temüjin united the many Turkic-Mongol confederations of Central Asia, giving a common identity to what had previously been a territory of nomadic tribes.

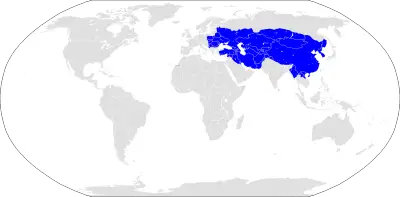

Starting with the conquest of Western Xia in northern China and consolidating through numerous conquests including the Khwarezmid Empire in Persia, Genghis Khan laid the foundation for an empire that was to leave an indelible mark on world history. Several centuries of Mongol rule across the Eurasian landmass, a period that some refer to as 'Pax Mongolica', radically altered the demography and geopolitics of these areas. The Mongol Empire ended up ruling, or at least briefly conquering, large parts of modern day China, Mongolia, Russia, Ukraine, Korea, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Moldova, Kuwait, Poland and Hungary.

Early life

Birth

Little is known about Temüjin's early life, and the few sources providing insight into this period do not agree on many basic facts. He was likely born around 1162[1] in the mountainous area of Burhan Haldun in Mongolia's Hentiy Province near the Onon and the Herlen (Kherülen) rivers. Folklore and legend stated that when Temujin was born he clutched a bloodclot in his fist, a divine sign that he was destined to do great things. He was the eldest son of Yesükhei, a minor tribal chief of the Kiyad and a nöker (vassal) of Ong Khan of the Kerait tribe[2], possibly descended from a family of blacksmiths (see below, name). Yesükhei's clan was called Borjigin (Боржигин), and his mother, Hoelun, was of the Olkhunut tribe of the Mongol confederation. They were nomads like almost all Central Asian Turkic and Mongol confederations.

Family

Genghis was related through his father to Qabul Khan, Ambaghai and Qutula Khan who had headed the Mongol confederation under Jin Dynasty patronage [citation needed] until the Jin switched support to the Tatars in 1161 and destroyed Qutula Khan. Genghis' father, Yesugei, khan of the Borjigin and nephew to Ambaghai and Qutula Khan, emerged as the head of the ruling clan of the Mongols, but this position was contested by the rival Tayichi’ud clan, who descended directly from Ambaghai. When the Tatars, in turn, grew too powerful after 1161, the Jin moved their support from the Tatars to the Kerait.

Temüjin had three brothers, Imaad (or Qasar), Khajiun, and Temüge, and one sister, Temülen (or Temulin), as well as two half-brothers, Bekhter and Belgutei.

Genghis Khan's empress and first wife Borte had four sons, Jochi (1185–1226), Chagatai (?—1241), Ögedei (?—1241), and Tolui (1190–1232). Genghis Khan also had many other children with his other wives, but they were excluded from the succession, and records on what daughters he may have had are scarce. The paternity of Genghis Khan's eldest son, Jochi, remains unclear to this day and was a serious point of contention in his lifetime. Soon after Borte's marriage to Temüjin, she was kidnapped by the Merkits and reportedly given to one of their men as a wife. Though she was rescued, she gave birth to Jochi nine months later, clouding the issue of his parentage.

This uncertainty over Jochi's true father was voiced most strongly by Chagatai, who probably wanted to make his succession clear [3]. According to The Secret History of the Mongols, just before the invasion of the Khwarezmid Empire by Genghis Khan, Chagatai declared before his father and brothers that he would never accept Jochi as Khagan (i.e., as Genghis Khan's successor). In response to this tension[4] and possibly for other reasons, it was Ögedei who was appointed as successor and who ruled as Khagan after Genghis Khan's death. Jochi died in 1226, before his father[5]. Genghis Khan himself never doubted Jochi's lineage; he claimed that he was his first son.

Childhood

Based on legends and later writers, Temüjin's early life was difficult. Yesukhei delivered Temüjin to the family of his future wife, members of the Onggirat tribe, when he was only nine as part of the marriage arrangement. He was supposed to live there in service to Deisechen, the head of the household, until he reached the marriageable age of 12. Shortly thereafter, his father was poisoned on his journey home by the neighboring Tatars in retaliation for his campaigns and raids against them. This gave Temüjin a claim to be the clan's chief, although his clan refused to be led by a mere boy and soon abandoned him and his family.

For the next few years, Temüjin and his family lived the life of impoverished nomads, surviving primarily on wild fruits, marmots and other small game. In one incident, Temüjin murdered his half-brother Bekhter over a dispute about sharing hunting spoils. Despite being severely reproached by his mother, he never expressed any remorse over the killing; the incident also cemented his position as head of the household. In another incident in 1182, he was captured in a raid by his former tribe, the Ta'yichiut, and held captive. The Ta'yichiut enslaved Temüjin (reportedly with a cangue), but he escaped with help from a sympathetic captor, the father of Chilaun, a future general of Genghis Khan. His mother, Hoelun, taught him many lessons about survival in the harsh landscape and even grimmer political climate of Mongolia, especially the need for alliances with others, a lesson which would shape his understanding in his later years. Jelme and Bo'orchu, two of Genghis Khan's future generals, joined him around this time. Along with his brothers, they provided the manpower needed for early expansion and diplomacy.

Temüjin married Börte of the Konkirat tribe around the age of 16, being betrothed as children by their parents as a customary way to forge a tribal alliance. She was later kidnapped in a raid by the Merkit tribe, and Temüjin rescued her with the help of his friend and future rival, Jamuka, and his protector, Ong Khan of the Kerait tribe. She remained his only empress, although he followed tradition by taking several morganatic wives. Börte's first child, Jochi, was born roughly nine months after she was freed from the Merkit, leading to questions about the child's paternity.

Temüjin became blood brother (anda) with Jamuqa, and thus the two made a vow to be faithful to each other for eternity.

From Temüjin to Genghis Khan

Temüjin began his slow ascent to power by offering himself as a vassal to his father's anda (sworn brother or blood brother) Toghrul, who was Khan of the Kerait and better known by the Chinese title Ong Khan (or "Wang Khan"), which the Jin Empire granted him in 1197. This relationship was first reinforced when Borte was captured by the Merkits; it was to Toghrul that Temüjin turned for support. In response, Toghrul offered his vassal 20,000 of his Kerait warriors and suggested that he also involve his childhood friend Jamuka, who had himself become khan of his own tribe, the Jajirats [6]. Alhough the campaign was successful and led to the recapture of Borte and utter defeat of the Merkits, it also paved the way for the split between the childhood friends, Temüjin and Jamuka.

Toghrul's son, Senggum, was jealous of Temüjin's growing power and he allegedly planned to assassinate Temüjin. Toghrul, though allegedly saved on multiple occasions by Temüjin, gave in to his son [7] and adopted an obstinate attitude towards collaboration with Temüjin. Temüjin learned of Senggum's intentions and eventually defeated him and his loyalists. One of the later ruptures between Toghrul and Temüjin was Toghrul's refusal to give his daughter in marriage to Jochi, the eldest son of Temüjin, which signified disrespect in the Mongol culture. This act probably led to the split between both factions and was a prelude to war. Toghrul allied himself with Jamuqa, Temüjin's blood brother, or anda, and when the confrontation took place, the internal divisions between Toghrul and Jamuka, as well as the desertion of many clans that fought on their side to the cause of Temüjin, led to Toghrul's defeat. This paved the way for the fall and extinction of the Kerait tribe.

The next direct threat to Temüjin was the Naimans, with whom Jamuka and his followers took refuge. The Naimans did not surrender, although enough sectors again voluntarily sided with Temüjin. In 1201, a Khuriltai elected Jamuka as Gur Khan, universal ruler, a title used by the rulers of the Kara-Khitan Khanate. Jamuka's assumption of this title was the final breach with Temüjin, and Jamuka formed a coalition of tribes to oppose him. Before the conflict, however, several generals abandoned Jamuka, including Subutai, Jelme's well-known younger brother. After several battles, Jamuka was finally captured in 1206 after several shepherds kidnapped and turned him over to Temüjin.

According to the pro-Genghis histories, Temüjin generously offered his friendship again to Jamuqa and asked him to turn to his side. Jamuqa refused and asked for a noble death, i.e., without spilling blood, which was granted (his back was broken). The rest of the Merkit clan that sided with the Naimans were defeated by Subutai (or Subedei), a member of Temüjin's personal guard who would later become one of the greatest commanders in the service of the Khan. The Naimans' defeat left Genghis Khan as the sole ruler of the Mongol plains. All these confederations were united and became known as the Mongols.

By 1206, Temüjin managed to unite the Merkits, Naimans, Mongols, Uyghurs, Keraits, Tatars and disparate other smaller tribes under his rule through his charisma, dedication, and strong will. It was a monumental feat for the "Mongols" (as they became known collectively), who had a long history of internecine dispute, economic hardship, and pressure from Chinese dynasties and empires. At a Kurultai, a council of Mongol chiefs, he was acknowledged as "Khan" of the consolidated tribes and took the title Genghis Khan. The title Khagan was not conferred on Genghis until after his death, when his son and successor, Ögedei took the title for himself and extended it posthumously to his father (as he was also to be posthumously declared the founder of the Yuan Dynasty). This unification of all confederations by Genghis Khan established peace between previously warring tribes. The population of the whole Mongol nation was around 200,000 people including civilians with approximately 70,000 soldiers at the formation of unified Mongol nation.

Military campaigns

First war with Western Xia

The Mongol Empire created by Genghis Khan in 1206 was bordered on the west by the Western Xia Dynasty. To its east and south was the Jin Dynasty, who at the time ruled northern China as well as being the traditional overlord of the Mongolian tribes. Temüjin organized his people and his state to prepare for war with Western Xia, or Xi Xia, that was closer to the Mongol border. He also knew that the Jin Dynasty had a young ruler who would not come to the aid of Tanguts of Xi Xia. This is what happened when the Tanguts asked the leader of Jin Dynasty for help and was refused. [8]

The Jurchen had also grown uncomfortable with the newly-unified Mongols. It may be that some trade routes ran through Mongol territory, and they might have feared the Mongols eventually would restrict the supply of goods coming from the Silk Road. On the other hand, Genghis Khan also was eager to take revenge against the Jurchen for their long subjugation of the Mongols. For example, the Jurchen were known to stir up conflicts between Mongol tribes and had even executed some Mongol Khans.

Eventually, Genghis Khan led his army against Western Xia and conquered it, despite initial difficulties in capturing its well-defended cities. By 1209, the Tangut emperor acknowledged Genghis as overlord.

In 1211, Genghis set about bringing the Nüzhen (the founders of the Jin Dynasty) completely under his dominion. The commander of Jin army made a tactical mistake in not attacking the Mongols at the first opportunity. Instead, the Jin commander sent a messenger, Ming-Tan, to the Mongol side, who promptly defected and told the Mongols that the Jin army was waiting on the other side of the pass. At this engagement fought at Badger Pass the Mongols massacred thousands of Jin troops. When the Taoist sage Ch'ang Ch'un was passing through this pass to meet Genghis Khan he was stunned to see the bones of so many people scattered in the pass. On his way back he stayed close to this pass for three days and prayed for the departed souls. The Mongol army crossed the Great Wall of China in 1213, and in 1215 Genghis besieged, captured, and sacked the Jin capital of Yanjing (later known as Beijing). This forced the Jin Emperor Xuan Zong to move his capital south to Kaifeng.

Conquest of the Kara-Khitan Khanate

Meanwhile, Kuchlug, the deposed Khan of the Naiman confederation, had fled west and usurped the Khanate of Kara-Khitan (also known as Kara Kitay), the western allies who had decided to side with Genghis. By this time the Mongol army was exhausted from ten years of continuous campaigning in China against the Tangut and the Rurzhen. Therefore, Genghis sent only two tumen (20,000 soldiers) against Kuchlug, under a brilliant young general, Jebe known as "The Arrow".

An internal revolt against Kuchlug was incited by Mongol agents, leaving the Naiman forces open for Jebe to overrun the country; Kuchlug's forces were defeated west of Kashgar. Kuchlug fled, but was hunted down by Jebe and executed, and Kara-Khitan was annexed by Genghis Khan.

By 1218, the Mongol Empire extended as far west as Lake Balkhash and it adjoined Khwarezmia, a Muslim state that reached to the Caspian Sea in the west and to the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea in the south.

Invasion of Khwarezmid Empire

After the defeat of the Kara-Khitais, the extensive Mongol Empire had a border with the Muslim state of Khwarezmia, governed by Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad. Genghis Khan saw the potential advantage in Khwarezmia as a commercial partner, and sent a 500-man caravan to officially establish trade ties with Khwarezmia. However Inalchuq, the governor of the Khwarezmian city of Otrar, attacked the caravan that came from Mongolia, claiming that the caravan was a conspiracy against Khwarezmia. The governor later refused to make repayments for the looting of the caravan and murder of its members. Genghis Khan then sent a second group of ambassadors to meet the Shah himself. The shah had all the men shaved and all but one beheaded. This was seen as an affront to Khan himself. This led Genghis Khan to attack the Khwarezmian Dynasty. The Mongols crossed the Tien Shan Mountains, coming into the Shah's empire.

After compiling information from many sources Genghis Khan carefully prepared his army, which was divided into three groups. His son Jochi led the first division into the Northeast of Khwarezmia. The second division under Jebe marched secretly to the Southeast part of Khwarzemia to form, with the first division, a pincer attack on Samarkand. The third division under Genghis Khan and Tolui marched to the northwest and attacked Khwarzemia from that direction.

The Shah's army were split by diverse internal disquisitions, and by the Shah's decision to divide his army into small groups concentrated in various cities — this fragmentation was decisive in Khwarezmia's defeats. The Shah's fearful attitude towards the Mongol army also did not help his army, and Genghis Khan and his generals succeeded in destroying Khwarizm.

Tired and exhausted from the journey, the Mongols still won their first victory against the Khwarezmian army. The Mongol army quickly seized the town of Otrar, relying on superior strategy and tactics. Once he had conquered the city, Genghis Khan executed many of the inhabitants and executed Inalchuq by pouring molten silver into his ears and eyes, as retribution for the insult.

According to stories, Khan diverted a river of Ala ad-Din Muhammad II of Khwarezm's birthplace, erasing it from the map. The Mongols' conquest of the capital was nothing short of brutal: the bodies of citizens and soldiers filled the trenches surrounding the city, allowing the Mongols to enter raping, pillaging and plundering homes and temples.

In the end, the Shah fled rather than surrender. Genghis Khan charged Subutai and Jebe with hunting him down, giving them two years and 20,000 men. The Shah died under mysterious circumstances on a small island within his empire.

By 1220 the Khwarezmid Empire was eradicated. After Samarkand fell, Bukhara became the capital of Jorezm, while two Mongol generals advanced on other cities to the north and the south. Jorezm, the heir of Shah Jalal Al-Din and a brilliant strategist, who was supported enough by the town, battled the Mongols several times with his father's armies. However, internal disputes once again split his forces apart, and Jorezm was forced to flee Bukhara after a devastating defeat.

Genghis Khan selected his third son Ögedei as his successor before his army set out, and specified that subsequent Khans should be his direct descendants. Genghis Khan also left Muqali, one of his most trusted generals, as the supreme commander of all Mongol forces in Jin China.

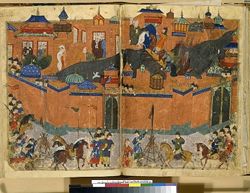

Attacks on Georgia and Volga Bulgaria

These campaigns were the start of Mongol invasion of Rus and Mongol invasion of Europe by almost two decades until 1240s.

The Mongol armies after conquering Khwarezmid Empire split into two component forces. Genghis Khan led a division on a raid through Afghanistan and northern India, while another contingent, led by his generals Jebe and Subutai, marched through the Caucasus and Russia. Neither campaign added territory to the empire, but they pillaged settlements and defeated any armies they met that did not acknowledge Genghis Khan as the rightful leader of the world. In 1225 both divisions returned to Mongolia. These invasions ultimately added Transoxiana and Persia to an already formidable empire.

While Genghis Khan gathered his forces in Persia and Armenia, a detached force of 20,000 troops, commanded by Jebe and Subutai, pushed deep into Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Mongols destroyed Georgians, sacked the Genoese trade-fortress of Caffa in Crimea, and stayed over winter near the Black Sea.

Heading home, Mongols assaulted the Kipchaks and were intercepted by the allied troops of Mstislav the Bold of Halych and Mstislav III of Kiev, along with about 80,000 Kievan Rus'. Subutai sent emissaries to the Slavic princes calling for separate peace, but the emissaries were executed. At the Battle of Kalka River in 1223, the Mongols defeated the larger Kievan force. The Russian princes then sued for peace. Subedei agreed but was in no mood to pardon the princes. As was customary in Mongol society for nobility the Russian princes were given a blood less death. Subedei had a large wooden platform constructed on which he ate his meals along with his other generals. Six Russian princes, including Mstislav of Kiev, were put under this platform and they suffocated to death.

Genghis Khan's army did lose to Volga Bulgars in the first attempt [citation needed], though they did come back to avenge their defeat by subjugating all Volga Bulgaria under the Khanate Golden Horde. Mongols also learned from captives of the abundant green pastures beyond the Bulgar territory, allowing for the planning for conquest of Hungary and Europe.

Genghis Khan recalled the forces back to the Mongolia soon afterwards, and Jebe died on the road back to Samarkand. This famous cavalry expedition of Subutai and Jebe, in which they encircled the entire Caspian Sea defeating every single army in their path, remains unparalleled to this day.

Second war with Western Xia and Jin Dynasty

The Mongol Empire campaigned six times against the Tanguts in 1202, 1207, 1209–1210, 1211–1213, 1214–1219 and 1225–1226. The vassal emperor of the Tanguts (Western Xia) had refused to take part in the war against the Khwarezmid Empire. While Genghis Khan was busy with the campaign in Persia against the Khwarezmid Empire, Tangut and Jin formed an alliance against the Mongols. In retaliation, Genghis Khan prepared for the last war against the Tanguts and their alliance.

In 1226, Genghis Khan began to attack the Tanguts. In February, he took Heisui, Ganzhou and Suzhou, and in the autumn he took Xiliang-fu. One of the Tangut generals challenged the Mongols to a battle near Helanshan (Helan means "great horse" in the northern dialect, shan means "mountain"). The Tangut armies were soundly defeated. In November, Genghis laid siege to the Tangut city Lingzhou, and crossed the Yellow River and defeated the Tangut relief army. Genghis Khan reportedly saw a line of five stars arranged in the sky, and interpreted it as an omen of his victory.

In 1227, Genghis attacked the Tangut capital, and continued to advance, seizing Lintiao-fu in February, Xining province and Xindu-fu in March, and Deshun province in April. At Deshun, the Tangut general Ma Jianlong put up a fierce resistance for several days and personally led charges against the invaders outside the city gate. Ma Jianlong later died from wounds received from arrows in battle. Genghis Khan, after conquering Deshun, went to Liupanshan (Qingshui County, Gansu Province) to escape the severe summer.

The new Tangut emperor quickly surrendered to the Mongols. The Tanguts officially surrendered in 1227, after having ruled for 189 years, beginning in 1038. Tired of the constant betrayal of Tanguts, Genghis Khan executed the emperor and his family. By this time, his advancing age had led Genghis Khan to make preparations for his death.

Mongol Empire

Politics and economics

The Mongol Empire was governed by civilian and military code, called the Yassa code created by Genghis Khan.

Among nomads, the Mongol Empire did not emphasize the importance of ethnicity and race in the administrative realm, instead adopting an approach grounded in meritocracy. The exception was the role of Genghis Khan and his family. The Mongol Empire was one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse empires in history, as befitted its size. Many of the empire's nomadic inhabitants considered themselves Mongols in military and civilian life, including Turks, Mongols, and others and included many diverse Khans of various ethnicities as part of the Mongol Empire such as Muhammad Khan.

There were to some degree ideals such as meritocracy among the Mongols and allied nomadic people in military and civilian life. However sedentary peoples, and especially the Chinese, remained heavily discriminated against. There were tax exemptions for religious figures and so to some extent teachers and doctors.

The Mongol Empire practiced religious tolerance to a large degree because it was generally indifferent to belief. The exception was when religious groups challenged the state. For example Ismaili Muslims that resisted the Mongols were exterminated.

The Mongol Empire linked together the previously fractured Silk Road states under one system and became somewhat open to trade and cultural exchange. However, the Mongol conquests did lead to a collapse of many of the ancient trading cities of Central Asia that resisted invasion. Taxes were also heavy and conquered people were used as forced labor in those regions.

Modern Mongolian historians say that towards the end of his life, Genghis Khan attempted to create a civil state under the Great Yassa that would have established the legal equality of all individuals, including women [1]. However, there is no contemporary evidence of this, or of the lifting of discriminatory policies towards sedentary peoples such as the Chinese, or any improvement in the status of women. Modern scholars refer to a theoretical policy of encouraging trade and communication as the concept of Pax Mongolica (Mongol Peace).

Genghis Khan realized that he needed people who could govern cities and states conquered by him. He also realised that such administrators could not be found among his Mongol people because they were nomads and thus had no experience governing cities. For this purpose Genghis Khan invited a Khitan prince, Chu'Tsai, who worked for the Jin and had been captured by Mongol army after the Jin Dynasty were defeated. Jin had captured power by displacing Khitan. Genghis told Chu'Tsai, who was a lineal descendant of Khitan rulers, that he had avenged Chu'Tsai's forefathers. Chu'Tsai responded that his father served the Jin Dynasty honestly and so did he; he did not consider his own father his enemy, so the question of revenge did not apply. Genghis Khan was very impressed by this reply. Chu'Tsai adminstered parts of the Mongol Empire and became a confidant of the successive Mongol Khans.

Military

- For detailed information about Mongol military, see Military advances of Genghis Khan and Mongol military tactics and organization.

Genghis Khan made advances in military disciplines, such as mobility, psychological warfare, intelligence, military autonomy, and tactics at the time

Genghis Khan and others are widely cited as producing a highly efficient army with remarkable discipline, organization, toughness, dedication, loyalty and military intelligence, in comparison to their enemies. The Mongol armies were one of the most feared forces ever to take the field of battle. Operating in massive sweeps, extending over dozens of miles, the Mongol army combined shock, mobility and firepower unmatched in land warfare until the modern age. Other peoples such as the Romans had stronger infantry, and others like the Byzantines deployed more heavily armored cavalry. Still others were experts in fortification. But none combined combat power on land with such devastating range, speed, scope and effectiveness as the Mongol military.

In contrast to most of their enemies, almost all Mongols were nomads and grew up on horses. Secondly, Genghis Khan refused to divide his troops into different ethnic units, instead creating a sense of unity. He punished severely even small infractions against discipline. He also divided his armies into a number of smaller groups based on the decimal system in units of 10s, taking advantage of the superb mobility of his mounted archers to attack their enemies on several fronts simultaneously. The soldiers took their families along with them on a military campaign. These units of 10s were like a family or close-knit group with a leader, and every unit of 10 had a leader who reported up to the next level of the 100s (10 leaders of 10s), 1,000s (10 leaders of 100s), 1,000s (10 leaders of 1,000s) or 1 tumen. The leader of the 100,000 (10 leaders of 10,000s) soldiers was the Khagan himself. Mongols in general were very used to living in cold and harsh winters and hot summers and they were very used to travelling very long distances without a difficulty since their settlement always changed depending on season and weather and with strict discipline and command under Genghis Khan and others made Mongol military highly efficient and better relying on scope of operation or space and the tactics, speed, and strategies that came out of it.

Genghis Khan expected unwavering loyalty from his generals and gave them free rein in battles and wars. Muqali, a trusted general, was given command of the Mongol forces over the Jin Dynasty while Genghis Khan was fighting in Central Asia, and Subutai and Jebe were allowed to use any means to defeat Kievan Rus. The Mongol military also was successful in siege warfare, cutting off resources for cities and towns by diverting rivers, causing inhabitants to become refugees, psychological warfare, and adopting new ideas, techniques and tools from the people they conquered.

Another important aspect of the military organization of Genghis Khan was the communications and supply route or Yam, borrowed from previous Chinese models. Genghis Khan dedicated special attention to this in order to speed up the gathering of military intelligence and support travelers.

Division of the Empire into Khanates

Before his death, Genghis Khan divided his empire among his sons and grandsons into several Khanates designed as sub-territories: their Khans were expected to follow the Great Khan, who was, initially, Ögedei Khan.

Following are the Khanates in the way in which Genghis Khan assigned after his death:

- Empire of the Great Khan or Yuan Dynasty - third son but designated main heir Ögedei Khan, as Great Khan, took most of Eastern Asia, including China.

- Il-Khanate - Hulegu Khan, son of Tolui and brother of Kublai Khan, established himself in the former Khwarezmid Empire as the Khan of the Il-Khanate.

- Mongol homeland (present day Mongolia, including Karakorum) - Tolui Khan, being the youngest son, received a small territory near the Mongol homeland, following Mongol custom.

- Chagatai Khanate - Chagatai Khan, Genghis Khan's second son, was given Central Asia and northern Iran.

- Blue Horde and White Horde (combined into the Golden Horde) -

Genghis Khan's eldest son, Jochi, had received most of the distant Russia and Ruthenia. Because Jochi died before Genghis Khan, his territory was further split up into the Western White Horde (under Orda Khan) and the Eastern Blue Horde, which under the Genghis Khan's grandson Batu Khan attacked Europe and crushed several armies before being summoned back by the news of Ögedei's death. In 1382, these two Khanates were combined by Tokhtamysh into the Kipchak Khanate, better known as the Golden Horde.

After Genghis Khan

Contrary to popular belief, Genghis Khan didn't conquer all of the areas of Mongol Empire, but his sons and grandsons did. At the time of his death, the Mongol Empire stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Sea of Japan. The empire's expansion continued for a generation or more after Genghis's death in 1227 — indeed, under Genghis's successor Ögedei Khan the speed of expansion reached its peak. Mongol armies pushed into Persia, finished off the Xi Xia and the remnants of the Khwarezmids, and came into conflict with the imperial Song Dynasty of China, starting a war that would last until 1279 and that would conclude with the Mongols gaining control of all of China.

In the late 1230s, the Mongols under Batu Khan started the Mongol invasions of Europe and Russia, reducing most of their principalities to vassalage, and pressed on into Central Europe. In 1241 Mongols under Subutai and Batu Khan defeated the last Polish-German and Hungarian armies at the Battle of Legnica and the Battle of Mohi.

During the 1250s, Genghis's grandson Hulegu Khan, operating from the Mongol base in Persia, destroyed the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad as well as the cult of the Assassins. It was rumoured that cult of the Assassins had sent 400 men to kill the Khagan Mongke Khan. The Khagan made this pre-emptive strike at the heart of the Islamic kingdom to make sure that no such assasination would take place. Hulegu Khan, the commander in chief of this campaign, along with his entire army returned back to the main Mongol capital Karakorum when he heard of Khagan Mongke Khan's death and left behind just two tumen of soldiers (20,000). A battle between a Mongol army and the Mamluks ensued in modern-day Palestine. Many in the Mamluk army were Slavs who had fought the Mongols years before as free men but were defeated and sold via Italian merchants to the Sultan of Cairo. They shared their experiences and were better prepared for Mongol tactics. The Mongol army lost the Battle of Ayn Jalut near modern-day Nazareth in part because a majority of the Mongol army had returned to Mongolia but also because this war was fought in summer when the land was parched and the Mongol armies could not keep enough mounts fed in the absence of pastures. This was the first defeat of the Mongol Empire in which they didn't return seek battle again. [9]

Mongol armies under Kublai Khan attempted two unsuccessful invasions of Japan and three unsuccessful invasions of modern-day Vietnam.

Death and burial

During his last campaign with the Tangut Empire during which Genghis Khan was fighting with the Khwarezmid Empire, Genghis Khan died on August 18, 1227. The reason for his death is uncertain. Many assume he fell off his horse, due to old age and physical fatigue; some contemporary observers cited prophecies from his opponents. The Galician-Volhynian Chronicle alleges he was killed by the Tanguts. There are persistent folktales that a Tangut princess, to avenge her people and prevent her rape, castrated him with a knife hidden inside her and that he never recovered.

Genghis Khan asked to be buried without markings. After he died, his body was returned to Mongolia and presumably to his birthplace in Hentiy aymag, where many assume he is buried somewhere close to the Onon River. According to legend, the funeral escort killed anyone and anything across their path, to conceal where he was finally buried. The Genghis Khan Mausoleum is his memorial, but not his burial site. On October 6, 2004, "Genghis Khan's palace" was allegedly discovered, and that may make it possible to find his burial site. Folklore says that a river was diverted over his grave to make it impossible to find (The same manner of burial of Sumerian King Gilgamesh of Uruk.) Other tales state that his grave was stampeded over by many horses, over which trees were then planted and the permafrost also did its bit in the hiding the burial site. The burial site remains undiscovered.

Genghis Khan left behind an army of more than 129,000 men; 28,000 were given to his various brothers and his sons, and Tolui, his youngest son, inherited more than 100,000 men. This force contained the bulk of the elite Mongolian cavalry. This was done because by tradition, the youngest son inherits his father's property. Jochi, Chagatai, Ogedei and Kulan's son Gelejian received armies of 4000 men each. His mother and the descendants of his three brothers received 3000 men each.

Genghis Khan's personality

Simplicity

It is not entirely clear what Genghis Khan's personality was truly like, but his personality and character were doubtlessly molded by the many hardships he faced when he was young, and in unifying the Mongol nation. Genghis appeared to fully embrace the Mongol people's nomadic way of life, and did not try to change their customs or beliefs. As he aged, he seemed to become increasingly aware of the consequences of numerous victories and expansion of the Mongol Empire, including the possibility that succeeding generations might choose to live a sedentary lifestyle. According to quotations attributed to him in his later years, he urged future leaders to follow the Yasa, and to refrain from surrounding themselves with wealth and pleasure. He was known to share his wealth with his people and awarded subjects handsomely who participated in campaigns.

Honesty and loyalty

He seemed to value honesty and loyalty highly from his subjects. Genghis Khan put some trust in his generals, such as Muqali, Jebe and Subudei, and gave them free rein in battles. He allowed them to make decisions on their own when they embarked on campaigns on their own very far from the Mongol Empire capital Karakorum. An example of Genghis Khan's perception of loyalty is written in The Secret History of the Mongols that one of his main military generals Jebe had been his enemy and shot his horse. When Jebe was captured, he said he shot his horse and that he would fight for him if he spared his life or would die if that's what he wished. The man who became known as Genghis Khan spared Jebe's life and made him part of his team

Yet, accounts of his life are marked by a series of betrayals and conspiracies. These include rifts with his early allies such as Jamuka and Wang Khan and problems with the most important Shaman. At the end of his life, he reportedly was considering an attack against his son Jochi. There is little reason to believe all of these were genuine. This may suggest a degree of paranoia in Genghis Khan's personality based on his earlier experiences.

Military strategy

His military strategies showed a deep interest in gathering good intelligence and understanding the motivations of his rivals. He seemed to be a quick student, adopting new technologies and ideas that he encountered, such as siege warfare. The Secret History makes it clear he was not physically courageous and even says he was afraid of dogs. Many stories and legends claim that Genghis Khan always was in the front in battles, but these may not be historically accurate. He seemed to have very little tolerance for resistance against his rule; this tendency persisted among later rulers such as Ogedei Khan, Kublai Khan, etc., who behaved in the same way. Some people attribute this to the fierce and harsh climates in Central Asian steppes.

Spirituality

Genghis Khan towards the later part of his life became interested in the ancient Buddhist and Tao religions. The Taoist monk Ch'ang Ch'un, who rejected invitations from Sung and Jin leaders, traveled more than 5000 kilometers to meet Genghis Khan close to the Afghanistan border. The first question Genghis Khan asked him was if the monk had some secret medicine that could make him immortal. The monk's negative answer disheartened Genghis Khan, and he rapidly lost interest in the monk. He also passed a decree exempting all followers of Taoist religion from paying any taxes. This made the Taoist religion very powerful at the expense of Buddhists. Genghis Khan was by and large tolerant of the multiple religions he encountered during the conquests as long as the people were obedient. However, all of his campaigns caused wanton and deliberate destruction of places of worship.[10] Religious groups were persecuted only if they resisted or opposed his empire.

By others

The chronicler Minhaj al-Siraj Juzjani left a description of Genghis Khan, written when the Khan was in his later years:

[Genghis Khan was] a man of tall stature, of vigorous build, robust in body, the hair on his face scanty and turned white, with cat's eyes, possessed of dedicated energy, discernment, genius, and understanding, awe-striking, a butcher, just, resolute, an overthrower of enemies, intrepid, sanguinary, and cruel.

By himself

Perhaps a rare insight into Genghis Khan's perspective of himself was recorded in a letter to the Taoist monk Ch'ang Ch'un. The letter was presumably not written by Genghis Khan himself, as tradition states that he was illiterate, but rather by a Chinese person at a later point and recorded as his in the Chinese histories. A passage from the letter states:

Heaven has abandoned China owing to its haughtiness and extravagant luxury. But I, living in the northern wilderness, have not inordinate passions. I hate luxury and exercise moderation. I have only one coat and one food. I eat the same food and am dressed in the same tatters as my humble herdsmen. I consider the people my children, and take an interest in talented men as if they were my brothers. We always agree in our principles, and we are always united by mutual affection. At military exercises I am always in front, and in time of battle am never behind. In the space of seven years I have succeeded in accomplishing a great work, and uniting the whole world in one empire. (Bretschneider)

Genghis Khan was also supposed to have endorsed the pleasures of murder, theft and rape by saying:

The greatest pleasure of a man is to vanquish your enemies and chase them before you, to rob them of their wealth and see those dear to them bathed in tears, to ride their horses and clasp to your bosom their wives and daughters.

Perceptions of Genghis Khan today

Positive perception of Genghis Khan

Negative views of Genghis Khan are persistent, but some historians are looking into positive aspects of Genghis Khan's conquests. Genghis Khan is sometimes credited with bringing the Silk Route under one cohesive political environment. Theoretically this allowed increased communication and trade between the West, Middle East and Asia by expanding the horizon of all three areas. In more recent times some historians point out that Genghis Khan instituted some levels of meritocracy and was, by Christian or Islamic standards but not East Asian, quite tolerant of many religions under his rule.

In Mongolia

Genghis Khan is regarded by many modern Mongolian observers as one of Mongolia's greatest leaders. He was to a large extent responsible for the emergence of Mongolia as a political and ethnic identity. There is also a chasm in the perception of his brutality - Mongolians often feel that the historical record, written for the most part by non-Mongolian observers, is unfairly biased against Genghis Khan and exaggerates his barbarism and butchery while underplaying his positive role, for example in founding the Mongol nation. He reinforced many Mongol traditions and provided stability for the Mongol nation at a time of great uncertainty as a result of both internal factors and outside influences. He also brought in cultural change and helped create a writing system for the Mongolian language based on existing Uyghur script.

In the early 1990s, when Mongolia repudiated communism and withdrew from the Russian bloc, Genghis Khan became a symbol of the free nation's identity. Some Mongolians call Mongolia, "Genghis Khan's Mongolia" or "Genghis' nation." Mongolians have given his name to many products, streets, buildings, and other places. For example his face is on the ₮500, ₮1000, ₮5000 and ₮10,000 Mongolian tugrug, the currency of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar's main international airport, for example, is known as Chinggis Khaan International Airport and he is viewed with great respect by virtually all Mongolians and Mongol-related ethnic groups, such as Buryats and Evenkhei. He is talked about with great pride by Mongolians.

In China

In modern China, the PRC has identified Genghis Khan as a "Chinese national hero" based on its new policy of appropriating non-Chinese figures as Chinese cultural icons. While Mongolians as of yet reject these claims, Chinese Communist officials point to the large population of ethnic Mongols living in the PRC and the Mongol's establishment of the Yuan dynasty in China as support for claiming Genghis Khan as part of Chinese legacy. Historically, Genghis Khan and his descendents did not consider themselves Chinese. Like the Manchus, Mongol leaders attempted to retain their cultural identity within a larger Han populace by formalized discrimination against native Chinese in style of dress, custom and marriage. Under Genghis Khan and his successors (including Kublai, who styled himself Emperor of China), ethnic Chinese were prohibited from government service in the Central Secretariat which administered the conquered Mongol holdings in China. Despite this, Genghis Khan remains an admired figure in China for his military successes, which have no parallel in the history of China.

Recognition

Genghis Khan is recognized in number of large and popular publications and by other authors, which include the following:

- Genghis Khan is ranked #29 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential people in history.

- An article that appeared in the Washington Post on December 31, 1995 selected Genghis Khan as "Man of the Millennium".

- Genghis Khan was nominated for the "Top 10 Cultural Legends of the Millennium" in 1998 by Dr G. Ab Arwel, voted by the five Judges, Prof. D Owain, Mr G Parry OBE, Dr. C Campbell of Oxford University, and Mr S Evans and Sir B. Parry of the International Museum of Culture, Luxembourg.

- National Geographic's 50 Most Important Political Leaders of All Time.

By other countries

In much of modern-day Turkey, Genghis Khan is looked on as a great military leader. In contrast, in Iraq and Iran, he is looked on as a leader who caused great damage and destruction. The invasions of Baghdad and Samarkand caused mass murders, for example. His descendant Hulagu Khan destroyed much of Iran's northern part. He is regarded as one of the most despised conquerors of Iran, along with Tamerlane, Attila and Alexander [citation needed]. In much of Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Hungary, Genghis Khan, his descendants and the Mongols and/or Tartars are generally described as causing considerable damage and destruction.

Consequences of Mongol conquest

There are many differing views on the amount of destruction Genghis Khan and his armies caused. The peoples who suffered the most during Genghis Khan's conquests, like the Persians and the Han Chinese, usually stress the negative aspects of the conquest and some modern scholars argue that their historians exaggerate the numbers of deaths. However such historians produce virtually all the documents available to modern scholars and so it is hard to establish a firm basis for any alternative view.

Casualties

In military strategy, Genghis Khan generally preferred to offer opponents the chance to submit to his rule without a fight and become vassals by sending tribute, accepting residents, contributing troops. He guaranteed them protection only if they abided by the rules under his administration and domain, but his and others' policy was mass destruction and murder if he encountered a resistance. For example David Nicole states in The Mongol Warlords, "terror and mass extermination of anyone opposing them was a well tested Mongol tactic." In such cases he would not give an alternative but ordered massive collective slaughter of the population of resisting cities and destruction of their property, usually by burning it to the ground. Only the skilled engineers and artists were spared from death and maintained as slaves. Documents written during or just after Genghis Khan's reign say that after a conquest, the Mongol soldiers looted, pillaged, and raped; however, the Khan got the first pick of the beautiful women. Some troops who submitted were incorporated into the Mongol system in order to expand their manpower; this also allowed the Mongols to absorb new technology, manpower, knowledge and skill for use in military campaigns against other possible opponents.

There also were instances of mass slaughter even where there was no resistance, especially in Northern China where the vast majority of the population had a long history of accepting nomadic rulers. Many ancient sources described Genghis Khan's conquests as wholesale destruction on an unprecedented scale, causing radical changes in the demographics of Asia. For example, over much of Central Asia speakers of Iranian languages were replaced by speakers of Turkic languages. According to the works of Iranian historian Rashid al-Din, the Mongols killed more than 70,000 people in Merv and more than a million in Nishapur. China suffered a drastic decline in population during 13th and 14th centuries. For instance, before the Mongol invasion, unified China had approximately 120 million inhabitants; after the conquest was completed in 1279, the 1300 census reported roughly 60 million people. [11] How many of these deaths were attributable directly to Genghis Khan and his forces is unclear, as are the highly generalized numbers themselves. In addition, some modern scholars question the validity of such estimates, since the methodology of the 1300 census likely underestimated the population. [citation needed]

On property and cultural treasures

His campaigns in Northern China, Central Asia and the Middle East caused massive property destruction for those who resisted his invasion; however, there are no exact factual numbers available at this time. For example, the cities of Ray and Tus, the two largest and most populous cities in Iran at the time, both centers of literature, culture, trade and commerce, were completely destroyed [citation needed] by order of Genghis Khan. Nishapur, Merv, Baghdad and Samarkand suffered similar destruction. There is a noticeable lack of Chinese literature that has survived from the Jin Dynasty, due to the Mongol conquests.

Modern descendants

Zerjal et al [2003] [12] identified a Y-chromosomal lineage present in about 8% of the men in a large region of Asia (about 0.5% of the men in the world). The paper suggests that the pattern of variation within the lineage is consistent with a hypothesis that it originated in Mongolia about 1,000 years ago. Such a spread would be too rapid to have occurred by diffusion, and must therefore be the result of selection. The authors propose that the lineage is carried by likely male-line descendants of Genghis Khan, and that it has spread through social selection.

In addition to the Khanates and other descendants, Babur's mother was a descendant.

Name and title

There are many theories for the origins of Temüjin's title; this uncertainty is fueled by the fact that later members of the Mongol Empire associated the name with the Mongol word for strength, ching, though this does not fit the etymology. One theory about the etymology suggests the name stems from a palatalised version of the Mongolian and Turkish word tenggiz, meaning "ocean," "oceanic" or "wide-spreading". Lake Baikal and ocean were called tenggiz by the Mongols. However, it seems that if they had meant to call Genghis tenggiz they could have said (and written) "Tenggiz Khan", which they did not. Zhèng (Chinese: 正, pron. "jung" in English) meaning "right", "just", or "true", would have received the Mongolian adjectival modifier -s, creating "Jenggis", which in medieval romanization would be written "Genghis". It is likely that contemporary Mongols would have pronounced the word more like "Chinggis". Chingis Khan is the spelling used by the modern Republic of Mongolia. [2] See Lister and Ratchnevsky, referenced below, for further reading.

According to legend, Temüjin was named after one of the more powerful chiefs of a rival tribe which his father, Yesükhei, had recently defeated. The name "Temüjin" is believed to derive from the Mongolian word temur, meaning iron. This name would imply skill as a blacksmith, and like any nomad of the time he was familiar, at least partially, with the working of iron for horse-shoeing and weaponry.

More likely, as no evidence has survived to indicate that Genghis Khan had any exceptional training or reputation as a blacksmith, the name indicated an implied lineage in a family once known as blacksmiths. The latter interpretation is supported by the names of Genghis Khan's siblings, Temulin and Temuge, which are derived from the same root word.

Short timeline

- c. 1155-1167 - Temüjin born in Hentiy, Mongolia.

- c. 1171 - Temüjin's father Yesükhei poisoned by the Tatars, leaving him and his family destitute

- c. 1184 - Temüjin's wife Borte kidnapped by Merkits; calls on blood brother Jamuka and Wang Khan for aid, and they rescued her.

- c. 1185 - First son Jochi born, leading to doubt about his paternity later among Genghis' children, because he was born soon after Borte's rescue from the Merkits.

- 1190' - Temüjin unites the Mongol tribes, becomes leader, and devises code of law Yassa.

- 1201 - Wins victory over Jamuka's Jadarans.

- 1202 - Adopted as Ong Khan's heir after successful campaigns against Tatars.

- 1203 - Wins victory over Ong Khan's Keraits.

- 1204 - Wins victory over Naimans (all these confederations are united and become the Mongols).

- 1206 - Temüjin given the title Genghis Khan by his followers in Kurultai (around 40 years of age).

- 1207-1210 - Genghis leads operations against the Western Xia, which comprises much of northwestern China and parts of Tibet. Western Xia ruler submits to Genghis Khan. During this period, the Uyghurs also submit peacefully to the Mongols and became valued administrators throughout the empire.

- 1211 - After Khuriltai, Genghis leads his armies against the Jin Dynasty that ruled northern China.

- 1219-1222 - Conquers Khwarezmid Empire.

- 1226 - Starts the campaign against the Western Xia for forming coalition against the Mongols, being the second battle with the Western Xia.

- 1227 - Genghis Khan dies leading fight against Western Xia. How he died is uncertain, although legend states that he was thrown off his horse in the battle, and contracted a deadly fever soon after.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rashid al-Din asserts that Genghis Khan lived to the age of 72, placing his year of birth at 1155. The Yuanshi (元史, History of the Yuan dynasty, not to be confused with the era name of the Han dynasty), records his year of birth as 1162. However, the Record of Successive Generations of Buddha (Lidai Fozu Tongzai) records that Genghis Khan died at the age of 60. According to Ratchnevsky, accepting a birth in 1155 would render Genghis Khan a father only at the age of 30, and would imply that at the ripe age of 72 he personally commanded the expedition against the Tanguts. Also, according to the Altan Tobci, Genghis Khan's sister, Temulin, was nine years younger than he; but the Secret History relates that Temulin was an infant during the attack by the Merkits, during which Genghis Khan would have been 18, had he been born in 1155. Zhao Hong reports in his travelogue that the Mongols he questioned did not and had never known their ages.

- ↑ Morgan, David, The Mongols (Peoples of Europe), 1990, p.58.

- ↑ Man, John Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0593050444.

- ↑ Ratchnevsky, Paul. Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy, 1991, p. 126.

- ↑ . Some scholars, notably Ratchnevsky, have commented on the possibility that Jochi was secretly poisoned by order of Genghis Khan. Rashid al-Din reports that the great Khan sent for his sons in the spring of 1223, and while his brothers heeded the order, Jochi remained in Khorasan. Juzjani suggests that the disagreement arose from a quarrel between Jochi and his brothers in the siege of Urgench, which Jochi attempted to protect from destruction as it belonged to territory allocated to him as a fief. He concludes his story with the clearly apocryphal statement by Jochi: "Genghis Khan is mad to have massacred so many people and laid waste so many lands. I would be doing a service if I killed my father when he is hunting, made an alliance with Sultan Muhammad, brought this land to life and gave assistance and support to the Muslims." Juzjani claims that it was in response to hearing of these plans that Genghis Khan ordered his son secretly poisoned; however, as Sultan Muhammad was already dead in 1223, the accuracy of this story is questionable. (Ratchnevsky, p. 136-7)

- ↑ Grousset, Rene. Conqueror of the World: The Life of Chingis-khan (New York: The Viking Press, 1944) SBN 670-00343-3.

- ↑ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0593050444.

- ↑ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0593050444.

- ↑ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0593050444.

- ↑ Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0593050444.

- ↑ Ping-ti Ho, "An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China", in Études Song, Series 1, No 1, (1970) pp. 33-53.

- ↑ Zerjal et. al, The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols, American Journal of Human Genetics, 2003.

External links

- Genghis Khan and the Mongols

- Welcome to The Realm of the Mongols

- Parts of this biography were taken from the Area Handbook series at the Library of Congress

- Coverage of Temüjin's Earlier Years

- Estimates of Mongol warfare casualties

- Genghis Khan on the Web (directory of some 250 resources)

- Mongol Arms

- LeaderValues

- ‘Ala’ al-Din ‘Ata Malik Juvayni (A History of the World-Conqueror Ghengis Genghis Khan, rashid-ad-din-juwayni ‘Ala’ al-Din ‘Ata Malik Juvayni)

- iExplore.com: The search for the missing tomb of Genghis Khan

- Genealogy of Genghis Khan's Ancestors from the "Generation Letter".

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World (New York : Crown, 2004) ISBN 0609610627.

- Kennedy, Hugh. Mongols, Huns & Vikings (London : Cassell, 2002) ISBN 0304352926.

- Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Retrieved June 30, 2005.

- Man, John. Genghis Khan : Life, Death and Resurrection (London; New York : Bantam Press, 2004) ISBN 0593050444.

- Lister, R. P. Genghis Khan (Lanham, Md. : Cooper Square Press, 2000 [c1969]) ISBN 0815410522.

- Mongol Arms. Mongol Arms. Retrieved June 24, 2003.

- Heirs to Discord: The Supratribal Aspirations of Jamuqa, Toghrul, and Temüjin

- Ratchnevsky, Paul. Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy [Čingis-Khan: sein Leben und Wirken] (Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA : B. Blackwell, 1992, c1991) tr. & ed. Thomas Nivison Haining, ISBN 0631167854.

- Bretschneider, Emilii. Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. ISBN 8121510031.

- Le Monde Diplomatique: "The destruction began with the genocide of the Tangut people of the Western Xia empire in northwest China. The Mongols razed many prosperous towns and reduced provinces to arid steppes, killing as they passed through: eventually they slaughtered some 600,000 Tanguts."[3]

- History of the Mongol Conquests, JJ Saunders, U. Pennsylvania Press, 1972: "The cold and deliberate genocide practiced by the Mongols, which has no parallel save that of the ancient Assyrians and the modern Nazis, perhaps arose from mixed motives of military advantage and superstitious fears..." From the really cool Google Print feature.

- Genocide: A Critical Bibliographic Review edited by Israel W Charney, 1994, lists the invasion of Afghanistan by Genghis as a genocide

- Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century by Benjamin A Valentino, gives the Mongols as one of the earliest examples

- Zerjal, Xue, Bertorelle, Wells, Bao, Zhu, Qamar, Ayub, Mohyuddin, Fu, Li, Yuldasheva, Ruzibakiev, Xu, Shu, Du, Yang, Hurles, Robinson, Gerelsaikhan, Dashnyam, Mehdi, Tyler-Smith (2003). The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols. The American Journal of Human Genetics (72): 717-721;.

Primary sources

- Juvaynī, Alā al-Dīn Atā Malik, 1226-1283. Genghis Khan: The History of the World-Conqueror [Tarīkh-i jahāngushā. English] (Seattle : UWashington Press, 1997) tr. John Andrew Boyle, ISBN 0295976543.

- The Secret History of the Mongols (Leiden; Boston : Brill, 2004) tr. Igor De Rachewiltz, Brill's Inner Asian Library. v.7, ISBN 9004131590.

- A Compendium of Chronicles: Rashid al-Din's Illustrated History of the World [Jami al-Tawarikh] (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1995) The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Vol. XXVII, ed. Sheila S. Blair, ISBN 019727627X.

- Tabib, Rashid al-Din. The Successors of Genghis Khan (New York : Columbia University Press, 1971) tr. from the Persian by John Andrew Boyle, [extracts from Jami’ Al-Tawarikh], UNESCO collection of representative works: Persian heritage series, ISBN 0231033516.

Further reading

- Cable, Mildred and Francesca French. The Gobi Desert (London: Landsborough Publications, 1943).

- Man, John. Gobi : Tracking the Desert (London : Weidenfield & Nicolson, 1997) hardbound; (London : Weidenfield & Nicolson, 1998) paperbound, ISBN 0753801612; (New Haven: Yale, 1999) hardbound.

- Stewart, Stanley. In the Empire of Genghis Khan: A Journey among Nomads (London: Harper Collins, 2001) ISBN 0-00-653027-3.

- History Channel's biography of Genghis Khan

- Secret History of the Mongols: The Origin of Chingis Khan (expanded edition) (Boston: Cheng & Tsui Asian Culture Series, 1998) adapted by Paul Kahn, ISBN 0887272991.

| Preceded by: (none) |

Khagan of Mongol Empire 1206–1227 |

Succeeded by: Ögedei Khan |

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Genghis Khan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Temüjin |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Founder of the Mongol Empire |

| DATE OF BIRTH | c. 1162 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | in Hentiy Aimag in Mongolia |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 18 1227 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Western Xia |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.