Great Wall of China

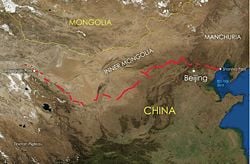

The Great Wall of China (Traditional Chinese: 萬里長城; Simplified Chinese: 万里长城; pinyin: Wànlǐ Chángchéng; literally "10,000 Li (里) long wall") is a series of stone and earthen fortifications in China, built, rebuilt, and maintained between the 3rd century B.C.E. and the 16th century to protect the northern borders of the Chinese Empire from raids by Hunnic, Mongol, Turkic, and other nomadic tribes coming from areas in modern-day Mongolia and Manchuria. Several walls referred to as the Great Wall of China were built since the third century B.C.E., the most famous being the wall built between 220 B.C.E. and 200 B.C.E. by the Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi. That wall was much further north than the current wall, and little of it remains.

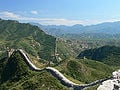

The current Great Wall, built primarily during the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644) is the world's longest man-made structure, stretching discontinuously today over approximately 6,400 km (3,900 miles), from the Bohai Sea in the east, at the limit between "China proper" and Manchuria, to Lop Nur in the southeastern portion of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Along most of its arc, it roughly delineates the border between North China and Inner Mongolia.

The Great Wall of China stands as a monument not only to the technological achievement of Chinese civilization, but also to both the tremendous cost of human conflict that motivated such investment in defense and also to the wisdom that peace begins with me and my people. The Ming Dynasty collapsed because of division within, not because the wall was breeched by force.

The Wall was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

History of the Great Wall of China

A defensive wall on the northern border was built and maintained by several dynasties at different times in Chinese history. There have been five major walls:

- 208 B.C.E. (Qin Dynasty)

- First century B.C.E. (Han Dynasty)

- Seventh century C.E. (Sui Dynasty)

- 1138–1198 (Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period)

- 1368–1640 (from Hongwu Emperor until Wanli Emperor of the Ming Dynasty)

The first major wall was built during the reign of the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang. This wall was not constructed as a single endeavor, but was mostly the product of joining several regional walls built by the Warring States. The walls that were linked together at this time consisted of rammed earth with watch towers built at regular intervals. It was located much further north than the current Great Wall with its eastern end at modern day North Korea. Very little of this first wall remains; photos reveal a low, long mound.

The government ordered people to work on the wall, and workers were under perpetual danger of being attacked by brigands. Because many people died while building the wall, it has obtained the gruesome title, "longest cemetery on Earth" or "the long graveyard." Possibly as many as one million workers died building the wall, though the true numbers cannot be determined. Contrary to some legends, the people that died were not buried in the wall, since decomposing bodies would have weakened the structure.

The later long walls built by the Han, the Sui, and the Ten Kingdoms period were also built along the same design. They were made of rammed earth with multi-story watch towers built every few miles. These walls have also largely vanished into the surrounding landscape, eroded away by wind and rain.

In military terms, these walls were more frontier demarcations than defensive fortifications of worth. Certainly Chinese military strategy did not revolve around holding the wall; instead, it was the cities themselves that were fortified.

The Great Wall which most tourists visit today was built during the Ming Dynasty, starting around the year 1368, with construction lasting until around 1640. Work on the wall started as soon as the Ming took control of China but, initially, walls were not the Ming's preferred response to raids out of the north. That attitude began to change in response to the Ming's inability to defeat the Oirat war leader Esen Taiji in the period 1449 to 1454 C.E. A huge Ming Dynasty army with the Zhengtong Emperor at its head was annihilated in battle and the Emperor himself held hostage in 1449.

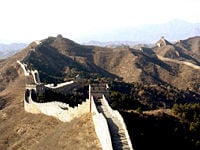

Apparently the real focus on wall building started as a result of Altan Khan's siege of Beijing which took place one hundred years later, in 1550. The Ming, faced with the choice of trying to defeat the Mongols with direct military force, chose instead to build a massive defensive barrier to protect China. As a result, most of the Ming Great Wall was built in the period 1560 to 1640. This new wall was built on a grand scale with longer lasting materials (solid stone used for the sides and the top of the Wall) than any wall built before.

The Ming Dynasty Great Wall starts on the eastern end at Shanhai Pass, near Qinhuangdao, in Hebei Province, next to Bohai Gulf. Spanning nine provinces and 100 counties, the final 500 km (~300 mi) have all but turned to rubble, and today it ends on the western end at the historic site of Jiayuguan Pass (also called Jiayu Pass) (嘉峪关), located in northwest Gansu Province at the limit of the Gobi Desert and the oases of the Silk Road. Jiayuguan Pass was intended to greet travelers along the Silk Road. Even though The Great Wall ends at Jiayu Pass, there are many watchtowers (烽火台 fēng huǒ tái) extending beyond Jiayu Pass along the Silk Road. These towers communicated by smoke to signal invasion.

In 1644 C.E., the Kokes Manchus crossed the Wall by convincing an important general Wu Sangui to open the gates of Shanhai Pass and allow the Manchus to cross. Legend has it that it took three days for the Manchu armies to pass. After the Manchu conquered China, the Wall was of no strategic value, mainly because the Manchu extended their political control far to the north. See more on the Manchu Dynasty.

Before the Second Sino-Japanese War, as a result of the failed defense of the Great Wall, the Great Wall became a de facto border between the Republic of China and Manchukuo.

Condition

While some portions near tourist centers have been preserved and even reconstructed, in many locations the Wall is in disrepair, serving as a playground for some villages and a source of stones to rebuild houses and roads. Sections of the Wall are also prone to graffiti. Parts have been destroyed because the Wall is in the way of construction sites. Intact or repaired portions of the Wall near developed tourist areas are often plagued with hawkers of tourist kitsch.

Watchtowers and barracks

The wall is complemented by defensive fighting stations, to which wall defenders could retreat if overwhelmed. Each tower has unique and restricted stairways and entries to confuse attackers. Barracks and administrative centers are located at larger intervals.

Materials

The materials used are those available near the wall itself. Near Beijing the wall is constructed from quarried limestone blocks. In other locations it may be quarried granite or fired brick. Where such materials are used, two finished walls are erected with packed earth and rubble fill placed in between with a final paving to form a single unit. In some areas the blocks were cemented with a mixture of sticky rice and egg whites.

In the extreme western desert locations, where good materials are scarce, the wall was constructed from dirt rammed between rough wood tied together with woven mats.

Recognition From Outer Space

There is a long standing tradition that the Great Wall is the only man-made object visible from orbit. This popular belief, which dates from at least the late nineteenth century, has persisted, assuming urban legend status, sometimes even entering school textbooks. Arthur Waldron, author of the most authoritative history of the Great Wall in any language, has speculated that the belief about the Great Wall's visibility from outer space might go way back to the fascination with the "canals" once believed to exist on Mars. (The logic was simple: If people on Earth can see the Martians' canals, the Martians might be able to see the Great Wall.)[1]

In fact, the Great Wall is only a few meters wide—sized similar to highways and airport runways—and is about the same color as the soil surrounding it. It cannot be seen by the unaided eye from the distance of the moon, much less that of Mars. The distance from Earth to the moon is about a thousand times greater than the distance from the Earth to a spacecraft in near-Earth orbit. If the Great Wall were visible from the moon, it would be easy to see from near-Earth orbit. In fact, from near-Earth orbit it is barely visible, and only under nearly perfect conditions, and it is no more conspicuous than many other man made objects.

Astronaut William Pogue thought he had seen it from Skylab but discovered he was actually looking at the Grand Canal of China near Beijing. He spotted the Great Wall with binoculars, but said that "it wasn't visible to the unaided eye."[2] United States Senator Jake Garn claimed to be able to see the Great Wall with the naked eye from a space shuttle orbit in the early 1980s, but his claim has been disputed by several professional U.S. astronauts. Chinese astronaut Yang Liwei said he could not see it at all.[3]

Veteran U.S. astronaut Eugene Andrew Cernan has stated: "At Earth orbit of 160 km to 320 km [96 to 192 miles] high, the Great Wall of China is, indeed, visible to the naked eye." Ed Lu, Expedition 7 Science Officer aboard the International Space Station, adds that, "it's less visible than a lot of other objects. And you have to know where to look."[4]

Neil Armstrong also stated:

- (On Apollo 11) I do not believe that, at least with my eyes, there would be any man-made object that I could see. I have not yet found somebody who has told me they've seen the Wall of China from Earth orbit. I'm not going to say there aren't people, but I personally haven't talked to them. I've asked various people, particularly Shuttle guys, that have been many orbits around China in the daytime, and the ones I've talked to didn't see it.[5]

Leroy Chiao, a Chinese-American astronaut, took a photograph from the International Space Station that shows the wall. It was so indistinct that the photographer was not certain he had actually captured it. Based on the photograph, the state-run China Daily newspaper concluded that the Great Wall can be seen from space with the naked eye, under favorable viewing conditions, if one knows exactly where to look.[6]

These inconsistent results suggest the visibility of the Great Wall depends greatly on the viewing conditions, and also the direction of the light (oblique lighting widens the shadow). Features on the moon that are dramatically visible at times can be undetectable at others, due to changes in lighting direction; the same would be true of the Great Wall. Nevertheless, one would still need very good vision to see the great wall from a space shuttle under any conditions.

More photos

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fryer, Jonathan. The Great Wall of China. South Brunswick, NJ: A.S. Barnes, 1977. ISBN 978-0498020988

- Geil, William E. The Great Wall of China. NY: Sturgis and Walton, 1909.

- Hitchcock, Romyn "The Great Wall of China," 327-32, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 45, Nov. 1892-April 1893.

- Lovell, Julia. The Great Wall: China against the World, 1000 B.C.E.-AD 2000. New York: Grove Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0802118141

- Michaud, Roland (Photographer), Sabrina Michaud (Photographer), and Michel Jan. The Great Wall of China New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0789207362

- Waldron, Arthur. The Great Wall of China: From History to Myth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0521365185

External links

All links retrieved May 24, 2024.

- Great Wall of China.

- Pictures of Great Wall of China.

- Great Wall of China.

- Great Wall of China.

- Great Wall visible in space photo. BBC News.

- The Great Wall of China.

- China imposes Great Wall ban. BBC News.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.