Manchukuo

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Manchukuo (1932–1945, 満州国, lit. "State of Manchuria") was a former puppet state created in 1932 by Imperial Japan in Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia, with the cooperation of former Qing Dynasty officials. The Japanese military, wishing to secure northeastern China as an industrial colony and source of raw materials, staged the Mukden Incident on September 18, 1931, as a pretext for taking over Manchuria. On February 18, 1932, Japan declared the establishment of the "Great Manchu Nation" (Manchukuo, Pinyin: Manzhouguo)[1]. The former Emperor of China, Puyi (溥儀), was installed by the Japanese as the ruler; real authority rested in the hands of Japanese military officials. The Manchu ministers served as front-men for their Japanese vice-ministers, who made all decisions. Japan developed industry and agriculture in Manchukuo, set up an education system, and built an extensive system of railroads and roads.

Japan used Manchukuo as a base for military expansion into China. On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchukuo from outer Manchuria in Operation August Storm. During the Soviet offensive, Japan's Army of Manchukuo performed poorly, and whole units surrendered to the Soviets without firing a single shot.

The Japanese declaration of Manchukuo as an “independent” state served as a challenge both to the civilian government in Japan and to the League of Nations. The Japanese government was forced to accede to the aggressive plans of the military. The League of Nations demonstrated its inability to deal with aggression, spending six months preparing a report, and four more months discussing it before finally passing a resolution, which Japan promptly defied. The establishment of Manchukuo by Japan prompted the United States to articulate the so-called Stimson Doctrine, under which international recognition was to be withheld from any changes in the international political system created by force of arms.

History

Russian influence

Manchuria, also known as “Dongbei” (“the Northeast”) was the homeland of the Manchu tribes who conquered China in 1644 and replaced the Ming Dynasty with the Qing. The Manchu emperors did not fully integrate Manchuria into China, and this legal, and to a degree ethnic, division persisted until the Qing dynasty began to fall apart in the 1800s.

As the power of the court in Beijing weakened, many outlying areas either broke free (like Kashgar) or fell under the control of Imperialist powers. In the 1800s, Imperial Russia became interested in the northern lands of the Qing Empire, which were rich in natural resources. In 1858, Russia gained nominal control over a large tract of land called Outer Manchuria through the Supplementary Treaty of Beijing that ended the Second Opium War. But Russia was not satisfied, and as the Qing Dynasty continued to weaken, they made further efforts to take control of the rest of Manchuria. Inner Manchuria came under strong Russian influence in the 1890s with the building of the Chinese Eastern Railway through Harbin to Vladivostok.

As a result of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 – 1905, Japanese influence replaced Russian in Inner Manchuria. In 1906, Japan laid the South Manchurian Railway to Port Arthur (Japanese: Ryojun). Between World War I and World War II Manchuria became a political and military battleground for Russia, Japan, and China. Japan took advantage of the chaos following the Russian Revolution of 1917 to move into Outer Manchuria. A combination of Soviet military successes and American economic pressure forced the Japanese to withdraw from the area, however, and Outer Manchuria had returned to Soviet control by 1925.

Mukden Incident

After the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the government of the Republic of China was installed with Yuan Shikai as President. However, Yuan soon began to act as a dictator, eliminating his political rivals and then trying to establish a new dynasty with himself as emperor. After his death in 1916, different parts of China fell under the control of a number of warlords, during what came to be known as the Warlord Period (1916 – 1928). [2] The warlord Zhang Zuolin established himself in Inner Manchuria with Japanese support.

By this time, the Japanese military had begun to take matters into their own hands, acting independently of the Japanese government in what they believed to be the best interests of Japan, and hoping to eventually force the civilian government to submit to military control. Some of the officers in the Japanese Kwantung Army, which occupied the Kwantung (Liaotung) Peninsula and patrolled the South Manchurian Railway zone, were ambitious to expand Japan’s influence in Manchuria, which had by now become a productive mining and industrial region and an important source of war materials for Japan. In June 1928, a Japanese army officer assassinated the warlord Zhang Zuolin by placing a bomb under a trestle of the South Manchurian Railway and exploding it as Zhang’s train passed underneath on another track. Though this action had not been authorized by the Tanaka government in Japan, it helped to bring the government down, and the civilian government became reluctant to curtail the activities of the military.

On September 18, 1931, the Mukden Incident (or Manchurian incident) launched Japanese aggression in East Asia. Japanese army officers detonated a bomb next to a small section of railway track near Mukden (now Shenyang), and claimed that Chinese soldiers had done it in an attempt to destroy a South Manchurian Railway train. The Japanese army used this incident as a pretext to seize Mukden, and then occupy all of Manchuria. The outraged Chinese held massive demonstrations against Japan and began to boycott Japanese goods. Zhang Xueliang, the son and successor of Zhang Zuolin, commanded a Kuomintang force in Manchuria large enough to resist the Japanese, but Chiang Kai-shek ordered him not to fight, deciding instead to appeal to the League of Nations. The Council of the League of Nations passed two resolutions, one on September 30 and the other on October 23, urging the Japanese to cease their military operations and enter into direct negotiations with China, and appointing a special commission to investigate the situation. The Japanese ignored the resolutions, and by the end of 1931 had routed all of Zhang’s Kuomintang troops from Manchuria.

Puyi installation as leader of Manchukuo

On February 18, 1932, Japan declared Manchuria’s independence from China and recognized the establishment of the "Great Manchu Nation" (Manchukuo, Pinyin: Manzhouguo)[3]. The former Emperor of China, Puyi (溥儀), was invited to come with his followers and act as the nominal head of state for Manchuria. Japanese agents forcibly brought Puyi to Manchukuo from his residence in Tianjin[4]. On March 1, 1932, Puyi was installed by the Japanese as the ruler of Manchukuo, under the reign title Datong (大同). In 1934, he was officially crowned the emperor of Manchukuo under the reign title Kangde (康德; “Tranquility and Virtue”); Manchukuo now became the "Great Manchu Empire." Puyi lived in the Wei Huang Gong( 伪皇宫), also known as “Puppet Emperor's Palace,” built by the Japanese Army. Zheng Xiaoxu served as Manchukuo's first prime minister until 1935, when Zhang Jinghui succeeded him. Puyi was nothing more than a figurehead; real authority rested in the hands of the Japanese military officials. The Manchu ministers served as front-men for their Japanese vice-ministers, who made all decisions.

In October of 1932, the Lytton Commission reported to the League of Nations, criticizing Japan’s violation of international treaties, and recommending that Manchuria be governed by an autonomous administration, under Chinese sovereignty, which would recognize Japan’s economic interests in the region.[5] The report was adopted by the League of Nations in 1933, and the next day, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations and issued a warning to other foreign nations. Japan then occupied the northern Chinese province of Rehol and annexed it to Manchukuo, and moved into Hubei Province.

Chinese in Manchuria organized volunteer armies to oppose the Japanese and the new state required a war, which lasted for several years, to pacify the country.

Of the 80 nations then in existence, only 23 recognized the new state. The Manchukuo case prompted the United States to articulate the so-called Stimson Doctrine, under which international recognition was withheld from changes in the international political system created by force of arms. Of the major powers Imperial Japan (September 16, 1932), the Soviet Union, Vichy France, Fascist Italy, Francoist Spain and Nazi Germany recognized Manchukuo diplomatically. In addition Manchukuo gained recognition from the Japanese collaborationist government of China under Wang Jingwei, as well as El Salvador and the Dominican Republic. Although the Chinese government did not recognize Manchukuo, the two countries established official ties for trade, communications and transportation.

Prior to World War II, the Japanese colonized Manchukuo and used it as a base from which to invade China. In the summer of 1939, a border dispute between Manchukuo and Mongolia resulted in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, in which a combined Soviet-Mongolian force defeated the Japanese Kantogun.

On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan in accordance with the agreement at the Yalta Conference, and invaded Manchukuo from outer Manchuria in Operation August Storm. During the Soviet offensive, the Army of Manchukuo, theoretically a two hundred-thousand-man force, well-armed and trained along Japanese lines, performed poorly, and whole units surrendered to the Soviets without firing a single shot; there were even cases of armed riots and mutinies against the Japanese forces. Emperor Kang De had hoped to escape to Japan and surrender to the Americans, but the Soviets captured him and eventually extradited him to the communist government in China, where the authorities had him imprisoned as a war criminal along with all other captured Manchukuo officials.

From 1945 to 1948, Manchuria (Inner Manchuria) served as a base area for the People's Liberation Army in the Chinese Civil War against the Kuomintang (KMT). With Soviet encouragement, the Chinese Communists used Manchuria as a staging ground until the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. Many Manchukuo army and Japanese Kantogun personnel served with the communist troops during the Chinese Civil War against the Nationalist forces.

Politics

Historians generally consider Manchukuo a puppet state or colony of Imperial Japan[6] because of the Japanese military's strong presence and strict control of the government administration, in addition to Japan's wartime atrocities against the local population in Manchukuo. Chinese historians generally refer to the state as 'Wei Manzhouguo' ('false Manchukuo') to emphasize its alleged lack of legitimacy.

Japan expanded industry and the transportation system in Manchukuo in order to develop it as a base for military campaigns against China. In addition, some historians regard Manchukuo as a Japanese effort to build an ideal state in Asia, which failed due to the pressures of war. The experience of administering and colonizing Manchuria had a considerable impact on the Japanese homeland; cooperation between the state and private industry, and military interests and private business, increased; new economic and agricultural policies were tested; political outcasts and “secondary citizens” were able to pursue new economic and career opportunities abroad; a mass political culture evolved; the government experimented with state capitalism; and the administration became aware of the need to develop a “unified front” against communist ideology. The exposure of large numbers of Japanese soldiers and civilians to Chinese culture gave rise to new styles of music, art and design.

Administrative Division of Manchukuo

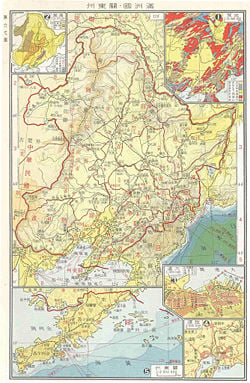

During its short-lived existence, Manchukuo was divided into between five (in 1932) and nineteen (in 1941) provinces, one special ward of Beiman (Japanese:北満特別区) and two “special cities,” Xinjing (Japanese: 新京特別市) and Harbin (Japanese: 哈爾浜特別市). Each province was divided into between four (Xingan-dong) and twenty-four (Fengtian) prefectures. Beiman lasted less than 3 years (July 1, 1933 - January 1, 1936) and Harbin was later incorporated into Binjiang province. Heilongjiang also existed as a province in 1932, before being divided into Heihe, Longjiang and Sanjiang in 1934. Andong and Jinzhou provinces separated themselves from Fengtian while Binjiang and Jiandao separated themselves in the same year from Kirin.

| Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | 1934 | 1937 | 1939 | 1941 | 1943 |

| Heilongjiang 龍江省 |

Heihe Kokuga 黒河省 |

Heihe Kokuga 黒河省 |

Heihe Kokuga 黒河省 |

Heihe Kokuga 黒河省 |

Heihe Kokuga 黒河省 |

| Sanjiang Sanko 三江省 |

Sanjiang Sanko 三江省 |

Sanjiang Sanko 三江省 |

Sanjiang Sanko 三江省 |

Sanjiang Sanko 三江省 | |

| Longjiang Ryuko 龍江省 |

Longjiang Ryuko 龍江省 |

Longjiang Ryuko 龍江省 |

Longjiang Ryuko 龍江省 |

Longjiang Ryuko 龍江省 | |

| Beian Hokuan 北安省 |

Beian Hokuan 北安省 |

Beian Hokuan 北安省 | |||

| Kirin 吉林省 |

Binjiang Hinko 濱江省 |

Binjiang Hinko 濱江省 | |||

| Binjiang Hinko 濱江省 |

Binjiang Hinko 濱江省 |

Binjiang Hinko 濱江省 | |||

| Mudanjiang Botanko 牡丹江省 |

Mudanjiang Botanko 牡丹江省 |

Mudanjiang Botanko 牡丹江省 |

東満総省 | ||

| Dongan Toan 東安省 |

Dongan Toan 東安省 |

東満総省 | |||

| Jiandao Kanto Gando 間島省 |

Jiandao Kanto Gando 間島省 |

Jiandao Kanto Gando 間島省 |

Jiandao Kanto Gando 間島省 |

東満総省 | |

| Jilin Kirin 吉林省 |

Jilin Kirin 吉林省 |

Jilin Kirin 吉林省 |

Jilin Kirin 吉林省 |

Jilin Kirin 吉林省 | |

| Fengtian 奉天省 |

Andong Anto 安東省 |

Andong Anto 安東省 |

Andong Anto 安東省 |

Andong Anto 安東省 |

Andong Anto 安東省 |

| Tonghua Tsuka 通化省 |

Tonghua Tsuka 通化省 |

Tonghua Tsuka 通化省 | |||

| Fengtian Hoten 奉天省 |

Fengtian Hoten 奉天省 |

Fengtian Hoten 奉天省 |

Fengtian Hoten 奉天省 |

Fengtian Hoten 奉天省 | |

| Xiping Shihei 四平省 |

Xiping Shihei 四平省 | ||||

| Jinzhou Kinshu 錦州省 |

Jinzhou Kinshu 錦州省 |

Jinzhou Kinshu 錦州省 |

Jinzhou Kinshu 錦州省 |

Jinzhou Kinshu 錦州省 | |

| Xingan Koan 興安省 |

Xingan 興安省 |

Xingan Koan 興安省 |

Xingan-bei Koan-Kita 興安北省 |

Xingan-bei Koan-Kita 興安北省 |

興安総省 |

| Xingan-dong Koan-higashi 興安東省 |

Xingan-dong Koan-higashi 興安東省 |

興安総省 | |||

| Xingan-nan Koan-minami 興安南省 |

Xingan-nan Koan-minami 興安南省 |

興安総省 | |||

| Xingan-xi Koan-nishi 興安西省 |

Xingan-xi Koan-nishi 興安西省 |

興安総省 | |||

| Rehe Netsuka 熱河省 |

Rehe Netsuka 熱河省 |

Rehe Netsuka 熱河省 |

Rehe Netsuka 熱河省 |

Rehe Netsuka 熱河省 |

Rehe Netsuka 熱河省 |

| Xinjing Shinkyō 新京特別市 |

Xinjing Shinkyō 新京特別市 |

Xinjing Shinkyō 新京特別市 |

Xinjing Shinkyō 新京特別市 |

Xinjing Shinkyō 新京特別市 |

Xinjing Shinkyō 新京特別市 |

Demographics

In 1908 Manchuria had a population of 15,834,000, which rose to 30,000,000 in 1931 and 43,000,000 in Manchukuo. The population maintained a ratio of 123 men to 100 women, and the total number in 1941 had reached 50,000,000.

In early 1934 the total population of Manchukuo was estimated as 30,880,000, with 6.1 persons forming the average family, and 122 men for each 100 women. These numbers included 29,510,000 Chinese, 590,760 Japanese, 680,000 Koreans, and 98,431 other nationalities (Russians, Mongols, etc). Around 80 percent of the population was rural. Other statistics indicate that in Manchukuo the population rose by 18,000,000.

Japanese sources give these numbers: in 1940 the total population of Heilongjiang, Jehol, Kirin, Liaoning (Fengtien) and Hsingan provinces totaled 43,233,954; or an Interior Ministry figure of 31,008,600. Another figure of the period evaluated the total population as 36,933,000 residents.

Around the same time that the Soviet Union was promoting the Siberian Jewish Autonomous Oblast across the Manchukuo-Soviet border, some Japanese officials promoted the Fugu Plan to attract Jewish refugees to Manchukuo as part of their colonization efforts. From naive readings of anti-Semitic propaganda, the Japanese believed that Jews had an innate capability to generate wealth, which they wanted to exploit by bringing wealthy investors to develop industry and commerce in Manchukuo. Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union made such a population transfer impossible, since the Axis powers did not control the necessary sea lanes. In the end, only a few Jews came to Manchukuo.

Large numbers of Koreans from northern Korea, which had been annexed by Japan in 1910, migrated to Manchuria thereafter, hoping to better provide for their families (as Japan routinely confiscated much of the rice they grew at home). Today, descendants of these migrant Koreans in China, in provinces bordering North Korea, number close to three million.

Population of Main Cities in 1940

- Yingkow (119,000 or 180,871 in 1940)

- Mukden (339,000 or 1,135,801 in 1940)

- Hsinking or Changchung (126,000 or 544,202 in 1940)

- Harbin (405,000 or 661,948 in 1940)

- Dairen (400,000 or 555,562 in 1939)

- Antung (92,000 or 315,242 in 1940)

- Kirin (119,000 or 173,624 in 1940)

- Tsitsihar (75,000 in 1940)

Japanese population

In 1931–1932 there were 100,000 Japanese farmers in Manchukuo; other sources mention 590,760 inhabitants of Japanese nationality. Other figures for Manchukuo speak of a Japanese population 240,000 strong, later growing to 837,000. In Hsinking they made up 25 percent of the population. The Japanese government had official plans projecting the emigration of 5 million Japanese to Manchukuo between 1936 and 1956. Between 1938 and 1942 a contingent of young farmers of 200,000 arrived in Manchukuo; joining this group after 1936 were 20,000 complete families. When Japan lost sea and air control of the Yellow Sea, this migration stopped.

When the Red Army invaded Manchukuo, they captured 850,000 Japanese settlers. With the exception of some civil servants and soldiers, these were repatriated to Japan in 1946–1947. Many Japanese orphans in China were left behind in the confusion and were adopted by Chinese families. Some of them were stigmatized as Japanese during the Cultural Revolution, and in the 1980s Japan began to organize a repatriation program for them; however, returnees often faced rejection by their biological families and poor prospects in Japan due to their insufficient command of the Japanese language.

Economy

Manchukuo experienced rapid economic growth and development of its social systems. Its factories were among the most advanced, making it one of the industrial powerhouses in the region. Manchukuo's steel production surpassed Japan's in the late 1930s. Many Manchurian cities were modernized during the Manchukuo era. The efficient and massive railway system built in Manchukuo continues to function well today.

Slave Labor and Bacteriological Weapons Experiments

According to a joint study by historians Zhifen Ju, Mitsuyochi Himeta, Toru Kubo and Mark Peattie, more than 10 million Chinese civilians were mobilized by the Showa period army for slave work in Manchukuo under the supervision of the Koa-in.[7]. Due to poor conditions and hard labor, many Chinese slave laborers became ill; the seriously ill were sometimes pushed into mass graves in order to avoid medical expenditure.[8]. The worst coal mining disaster in history occurred on April 26, 1942, at the Benxihu Colliery in Manchukuo, when a gas and coal-dust explosion killed 1,549 miners.

Some of Japan’s worst war atrocities were carried out in Manchukuo. As many as ten thousand people, both civilian and military, of Chinese, Korean, Mongolian, and Russian origin were used as subjects of experiments with Bacteriological weapons conducted by Unit 731 near Harbin in Beinyinhe from 1932 to 1936, and in Pingfan until 1945.[9] Some American and European Allied prisoners of war also died at the hands of Unit 731. Victims were sometimes subjected to vivisection without anesthesia.[10] The use of biological weapons researched in Unit 731's bioweapons program resulted in tens of thousands of deaths in China, and by some estimates, as many as 200,000 casualties [11]

Education

Manchukuo developed an efficient public education system, setting up or founding many schools and technical colleges, 12,000 primary schools, 200 middle schools, 140 normal schools (for preparing teachers), and 50 technical and professional schools. In total the system had 600,000 children and young pupils and 25,000 teachers. There were 1,600 private schools (with Japanese permits), 150 missionary schools and, in Harbin, 25 Russian schools.

Education focused on practical work training for boys and domestic work for girls, all based on Confucian adherence to the "Kingly Way" and stressing loyalty to the Emperor. In rural areas, students were trained to practice modern agricultural techniques to improve production. Confucian teachings also played an important role in Manchukuo's public school education. Japanese became the official language in addition to the Chinese language taught in Manchukuo schools.

The Manchukuo regime used numerous festivals, sport events, and ceremonies to foster the loyalty of its citizens.

Stamps and Postal History

Manchukuo issued its first postage stamps on July 28, 1932. A number of denominations existed, with two designs: the pagoda at Liaoyang and a portrait of Puyi. Originally, the inscription read (in Chinese) "Manchu State Postal Administration"; in 1934, a new issue read "Manchu Empire Postal Administration." An orchid crest design appeared in 1935, and a design featuring the Sacred White Mountains in 1936.

In 1936 a new regular series was issued, featuring various scenes and surmounted by the orchid crest. Between 1937 and 1945, the government issued a variety of commemoratives: for anniversaries of its own existence, to note the passing of new laws, and to honor Japan in various ways, for instance, on the 2600th anniversary of the Japanese Empire in 1940. The last stamp issue of Manchukuo was on May 2, 1945, commemorating the 10th anniversary of an edict.

After the dissolution of the government, successor postal authorities locally handstamped many of the remaining stamp stocks with "Republic of China" in Chinese, and between 1946 and 1949, the Port Arthur and Dairen Postal Administration overprinted many Manchukuo stamps.

Notes

- ↑ Ernest R. May, Between World Wars. grolier.com. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Dorothy Perkins. Encyclopedia of China: the essential reference to China, its history and culture. (New York: Facts on File, 1999), 426

- ↑ Between World Wars. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Perkins, 306

- ↑ Perkins, 306

- ↑ [1] Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. article on "Manchukuo." bartelby.net. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Zhifen Ju, Japan's atrocities of conscripting and abusing north China draftees after the outbreak of the Pacific war. Paper delivered to June 2002 conference: Joint Study of the Sino-Japanese War [2].U.S. Peace Institute and others. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ↑ Huludao Shi. Huludao bai wan Ri qiao da qian fan. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Book on Japan’s germ warfare crimes published. China Daily, 2003-10-17 17:14. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Archives give up secrets of Japan’s Unit 731. Peoples Daily Online, UPDATED: 09:58, August 03, 2005. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Biological Weapons Program, GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beasley, W. G. 1987. Japanese imperialism, 1894-1945. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198215754

- Duara, Prasenjit. 2003. Sovereignty and authenticity: Manchukuo and the East Asian modern. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0742525775

- Duus, Peter, Ramon Hawley Myers, and Mark R. Peattie. 1989. The Japanese informal empire in China, 1895-1937. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691055610

- Ju, Zhifen, "Japan's atrocities of conscripting and abusing north China draftees after the outbreak of the Pacific war." Paper delivered to June 2002 conference: Joint Study of the Sino-Japanese War. U.S. Peace Institute.

- Morton, W. Scott, and Charlton M. Lewis. 2005. China: its history and culture. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0071412794

- Perkins, Dorothy. 1999. Encyclopedia of China: the essential reference to China, its history and culture. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816026939

- Smith, Norman. 2007. Resisting Manchukuo: Chinese women writers and the Japanese occupation. Contemporary Chinese studies. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 9780774813358

| Personal Names | Period of Reigns | era names (年號) and their corresponding range of years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All given names in bold. | ||||

| Aixinjuelo Puyi 愛新覺羅溥儀 | March 1932–August 1945 | Datong (大同 da4 tong2) 1932 Kangde (康德 kang1 de2) 1934 | ||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Manchukuo history

- Puyi history

- Imperial_Japanese_colonialism_in_Manchukuo history

- Mukden_Incident history

- Zhang_Zuolin history

- Lytton_Report history

- Fugu_Plan history

- Benxihu_Colliery history

- Unit_731 history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.