Difference between revisions of "Chemical bond" - New World Encyclopedia

David Burton (talk | contribs) m |

David Burton (talk | contribs) m (→Hydrogen Bond) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

A '''chemical bond''' is the phenomenon of [[atom]]s being held together to form [[molecule]]s or [[crystal]]s. All chemical bonds result from electrostatic interactions and/or from sharing of [[electron]]s, and derive from the action of the electromagnetic force. Where the electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental interactions of the physical universe. Electrostatic forces arise from the coulombic attraction or repulson between charged particles. On the other hand the sharing of electrons is described by quantum mechanics in [[Valence bond theory]] and [[Molecular orbital theory]]. | A '''chemical bond''' is the phenomenon of [[atom]]s being held together to form [[molecule]]s or [[crystal]]s. All chemical bonds result from electrostatic interactions and/or from sharing of [[electron]]s, and derive from the action of the electromagnetic force. Where the electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental interactions of the physical universe. Electrostatic forces arise from the coulombic attraction or repulson between charged particles. On the other hand the sharing of electrons is described by quantum mechanics in [[Valence bond theory]] and [[Molecular orbital theory]]. | ||

| − | There are 5 different | + | There are 5 different classes of chemical bonds that we use to categorize bonding. Actual bonds may have have properties that aren't so discretely categorized, so a given bond could be defined by more than one of these terms. |

| − | ==The | + | ==The Ionic Bond== |

| − | + | {{originalarticle|ionic bond}} | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | An '''ionic bond''' can be formed after two or more [[atoms]] lose or gain [[electron]]s to form an [[ion]]. Ionic bonds occur between [[metal]]s, losing electrons, and [[non-metal]]s, gaining electrons. Ions with opposite [[charge]]s will attract one another creating an ionic bond. Such bonds are stronger than [[hydrogen bond]]s, but similar in strength to [[covalent bond]]s. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <!-- The \,\! are to keep the formulae rendered as PNG instead of HTML. Please don't remove them.—> | |

| + | : <math>Li + F\ \ \ \to\ \ \ Li^+F^-\,\!</math> | ||

| + | : <math>3Na + P\ \ \ \to\ \ \ Na^+_3P^{3-}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It only occurs if the overall energy change for the reaction is favourable (the bonded atoms have a lower energy than the free ones). The larger the energy change the stronger the bond. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Pure'' ionic bonding doesn't actually happen with real atoms. All bonds have a small amount of [[covalent bond|covalency]]. The larger the difference in [[electronegativity]] the more ionic the bond. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table align="right" width="70%" cellpadding ="10" border="1"> | ||

| + | <tr><td>[[Image:Ionic bonding.png]]</td> <td align="middle">[[image:ionicbond.JPG]]</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td> <font face="Arial" size=1> | ||

| + | The diagram above shows the electron configurations of lithium and fluorine. Note that lithium has one electron in its outer shell. This electron is held rather loosely (''because the ionisation energy is very different in the two ions''). Note also that fluorine has 7 electrons in its outer shell. If the electron moves from lithium to fluorine each ion acquires the configuration of a [[noble gas]]. The bonding energy (from the [[electrostatic attraction]] of the two oppositely charged ions) is large enough (negative value) that the overall bonded state energy is lower than the unbonded state. | ||

| + | </font></td> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <td><font face="Arial" size=1> | ||

| + | Impression of two ions (for example [Na]<sup>+</sup> and [Cl]<sup>-</sup>) forming an ionic bond. [[Electron orbital]]s generally do not overlap (ie. [[molecular orbital]]s are not formed), because each of the ions reached the lowest [[energy state]], and the bond is based only (ideally) on the electrostatic interactions between positive and negative ions. | ||

| + | </font></td></tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Difference between ionic and covalent bonds=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an ionic bond, the atoms are bound by attraction of opposite ions, whereas in a covalent bond, atoms are bound by sharing electrons. In covalent bonding, the geometry around each atom is determined by [[VSEPR]] rules, whereas in ionic materials, the geometry follows maximum packing rules. Thus, a compound can be classified as ionic or covalent based on the geometry of the atoms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{chem-stub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Chemistry]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Chemical bonding]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[de:Ionische Bindung]] | ||

| + | [[et:Iooniline side]] | ||

| + | [[es:Enlace iónico]] | ||

| + | [[fr:Liaison ionique]] | ||

| + | [[it:Legame ionico]] | ||

| + | [[he:קשר יוני]] | ||

| + | [[nl:Ionaire binding]] | ||

| + | [[ja:イオン結合]] | ||

| + | [[nn:Ionebinding]] | ||

| + | [[pt:Ligação iônica]] | ||

| + | [[sl:Ionska vez]] | ||

| + | [[fi:Ionisidos]] | ||

| + | [[th:พันธะไอออน]] | ||

| + | [[zh:离子键]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==The Covalent Bond== | ||

| + | {{Originalarticle|covalent bond}} | ||

| + | |||

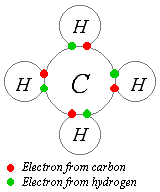

| + | [[Image:covalent.png|right|frame|Covalently bonded hydrogen and carbon in a molecule of [[methane]]. One way of representing covalent bonding in a molecule is with a [[dot and cross diagram]].]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Covalent bonding''' is a form of [[chemical bond]]ing characterized by the sharing of one or more pairs of [[electron]]s between two elements, producing a mutual attraction that holds the resultant [[molecule]] together. [[Atom]]s tend to share electrons in such a way that their outer [[electron shell]]s are filled. Such bonds are always stronger than the [[intermolecular force|intermolecular]] [[hydrogen bond]] and similar in strength to or stronger than the [[ionic bond]]. While covalent bonding most often occurs between atoms, metals can form covalent bonds with other covalent bonds themselves which can complicate matters somewhat. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Covalent bonding most frequently occurs between atoms with similar [[electronegativity|electronegativities]]. For this reason, non-metals tend to engage in covalent bonding more readily since metals have access to metallic bonding, where the easily-removed electrons are freer to roam about. For non-metals, liberating an electron is more difficult, so sharing is the only option when confronted with another species of similar electronegativity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, covalent bonding in metals and, particularly between metals and [[organic compound]]s is particularly important, especially in industrial catalysis and process chemistry, where many indispensible reactions depend on covalent bonding with metals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===History=== | ||

| + | [[image:electron_dot.png|left|300px|]] | ||

| + | The idea of covalent bonding can be traced to [[Gilbert N. Lewis]], who in [[1916]] described the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. He introduced the so called ''[[Lewis Structure|Lewis Notation]]'' or ''[[Electron Dot Structure|Electron Dot Notation]]'' in which valence electrons (those in the outer shell) are represented as dots around the atomic symbols. Pairs of electrons located between atoms represent covalent bonds. Multiple pairs represent multiple bonds, such as double and triple bonds. Some examples of Electron Dot Notation are shown in the following figure. An alternative form, in which bond-forming electron pairs are represented as solid lines, is shown in blue. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the idea of shared electron pairs provides an effective qualitative picture of covalent bonding, [[quantum mechanics]] is needed to understand the nature of these bonds and predict the structures and properties of simple molecules. [[Walter Heitler|Heitler]] and [[Fritz London|London]] are credited with the first successful quantum mechanical explanation of a chemical bond, specifically that of [[molecular hydrogen]], in [[1927]]. Their work was based on the valence bond model, which assumes that a chemical bond is formed when there is good overlap between the [[atomic orbitals]] of participating atoms. These atomic orbitals are known to have specific angular relationships between each other, and thus the valence bond model can successfully predict the bond angles observed in simple molecules. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Bond order=== | ||

| + | [[Bond order]] is the scientific term used to describe the number of pairs of electrons shared between atoms forming a covalent bond. | ||

| + | The most common type of covalent bond is the '''single bond''', the sharing of only one pair of electrons between two individual atoms. All bonds with more than one shared pair are called '''multiple covalent bonds'''. The sharing of two pairs is called a '''double bond''' and the sharing of three pairs is called a '''triple bond.''' An example of a double bond is [[nitrous acid]] (between N and O), and an example of a triple bond is in [[hydrogen cyanide]] (between C and N). | ||

| + | |||

| + | A single bond usually consists of one [[sigma bond]], a double bond of one sigma and one [[pi bond]], and a triple bond of one sigma and two pi bonds. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Quadruple bonds''', though rare, also exist. Both [[carbon]] and [[silicon]] can theoretically form these; however, the formed molecules are explosively unstable. Stable quadruple bonds are observed as transition metal-metal bonds, usually between two transition metal atoms in [[organometallic]] compounds. [[Molybdenum]] and [[Ruthenium]] are the elements most commonly observed with this bonding configuration. An example of a quadruple bond is also found in [[Di-tungsten tetra(hpp)]]. [[Quintuple Bond]]s are found to exist in certain [[chromium]] dimers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Sextuple bonds''' of order 6 have also been observed in transition metals in the gaseous phase at very low temperatures and are extremely rare. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other more exotic bonds, such as [[three center bond]]s are known and defy the conventions of bond order. It is also important to note that bond order is an integer value only in the elementary sense and is often fractional in more advanced contexts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Rigidity=== | ||

| + | Typically, two atoms can rotate about a single bond with relative ease. However, double and triple bonds are very difficult to rotate because they require pi orbital overlap. Pi orbital overlaps are parallel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Resonance=== | ||

| + | Some structures can have more than one valid Lewis Dot Structure (for example, [[ozone]], O<sub>3</sub>). In an LDS diagram of O<sub>3</sub>, the center atom will have a single bond with one atom and a double bond with the other. The LDS diagram cannot tell us which atom has the double bond; the first and second adjoining atoms have equal chances of having the double bond. These two possible structures are called [[chemical resonance|resonance structures]]. In reality, the structure of ozone is a '''resonance hybrid''' between its two possible resonance structures. Instead of having one double bond and one single bond, there are actually two 1.5 bonds with approximately three electrons in each at all times. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A special resonance case is exhibited in [[aromatic]] rings of atoms (for example, [[benzene]]). Aromatic rings are composed of atoms arranged in a circle (held together by covalent bonds) that alternate between single and double bonds according to their LDS. In actuality, the electrons tend to be disambiguously and evenly spaced within the ring. Electron sharing in aromatic structures is often represented with a ring inside the circle of atoms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Current theory=== | ||

| + | Today the valence bond model has been supplemented with the [[molecular orbital]] model. In this model, as atoms are brought together, the ''atomic'' orbitals interact to form '''hybrid''' ''molecular'' orbitals. These molecular orbitals are a cross between the original atomic orbitals and generally extend between the two bonding atoms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using quantum mechanics it is possible to calculate the electronic structure, energy levels, bond angles, bond distances, dipole moments, and frequency spectra of simple molecules with a high degree of accuracy. Currently, bond distances and angles can be calculated as accurately as they can be measured (distances to a few pm and bond angles to a few degrees). For the case small molecules, energy calculations are sufficiently accurate to be useful for determining thermodynamic heats of formation and kinetic activation energy barriers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===See also=== | ||

| + | * [[chemical bond]] | ||

| + | * [[ionic bond]] | ||

| + | * [[linear combination of atomic orbitals]] | ||

| + | * [[metallic bond]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===External links=== | ||

| + | *[http://wps.prenhall.com/wps/media/objects/602/616516/Chapter_07.html Covalent Bonds and Molecular Structure] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Chemistry]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Chemical bonding]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[ar:رابطة تساهمية]] | ||

| + | [[bg:Ковалентна химична връзка]] | ||

| + | [[ca:Enllaç covalent]] | ||

| + | [[da:Kovalent]] | ||

| + | [[de:Atombindung]] | ||

| + | [[et:Kovalentne side]] | ||

| + | [[es:Enlace covalente]] | ||

| + | [[fa:پیوند کووالانسی]] | ||

| + | [[fr:Liaison covalente]] | ||

| + | [[he:קשר קוולנטי]] | ||

| + | [[nl:Covalente binding]] | ||

| + | [[ja:共有結合]] | ||

| + | [[nn:Kovalent binding]] | ||

| + | [[pl:Wiązanie kowalencyjne]] | ||

| + | [[pt:Ligação covalente]] | ||

| + | [[fi:Kovalenttinen sidos]] | ||

| + | [[sv:Kovalent bindning]] | ||

| + | [[zh:共价键]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Metallic Bond== | ||

| + | The traditional picture of the '''metallic bond''' was developed soon after the discovery of the electron. In this picture the valence [[electron]]s were viewed as an electron-gas permeating the [[crystal lattice]] structre of the metal atoms. The cohesive forces holding the metal together could be qualitatively seen as resulting from the [[electrostatic]] interaction of the positively charged metal atom cores with the negatively charged electron-gas. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With the development of [[quantum mechanics]] this picture has changed significantly. Quantum mechanically [[Covalent bond|covalent bonding]] can be described by constructing [[Molecular orbital theory|molecular orbitals]] from a linear combination of atomic orbitals ([[LCAO theory]]). For some molecules, such as benzene, which contain [[resonance]] in an extended [[conjugation|conjugated]] system, some of the molecular orbitals are delocalized and the electrons not fixed between particular atoms. Applying these concepts to metals leads to the Band theory of solids. In this theory the metallic bond is similar to the delocalized molecular orbitals of benzene, but on a much larger scale and with the bonding spread throughout the metal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let us consider a [[sodium]] atom. It has one valence electron in an s [[orbital]]. When we add another atom the overlap of the two s orbitals results in two molecular orbitals of differing energies. Adding a third atom results in three molecular orbitals and so on. In a small lump of sodium there are many thousands of atoms and consequently many thousands of molecular orbitals whose energies lie close together, This results in an energy band populated by the available electrons that is called the s-band. Similarly, with other atoms, you can also get a p-band from the overlap of atomic p orbitals. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[semiconductors]] there is a significant energy difference between different bands called a band gap. This is what gives semiconductors their usefull properties exploited in electronic circuits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Hydrogen Bond== | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Originalarticle|hydrogen bond}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Wasserstoffbrückenbindungen des Wasser.png|thumb|Hydrogen bonds between water molecules are diagramatically represented by the black lines. The red lines are covalent bonds that hold oxygen (red) and hydrogen (blue) atoms together in the water molecules.]] | ||

| + | In [[chemistry]], a '''hydrogen bond''' is a type of attractive [[intermolecular force]] that exists between two [[partial charge|partial]] [[electric charge]]s of opposite polarity. Although stronger than most other intermolecular forces, the typical hydrogen bond is much weaker than both the [[ionic bond]] and the [[covalent bond]]. Within [[macromolecule]]s such as [[protein]]s and [[nucleic acid]]s, it can exist between two parts of the same molecule, and figures as an important constraint on such molecules' overall shape. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As the name "hydrogen bond" implies, one part of the bond involves a [[hydrogen]] [[atom]]. The hydrogen must be attached to a strongly [[electronegative]] | ||

| + | [[heteroatom]], such as [[oxygen]], [[nitrogen]] or [[fluorine]], which is called the hydrogen-bond ''donor''. This electronegative element attracts the electron cloud from around the hydrogen nucleus and, by decentralizing the cloud, leaves the atom with a positive partial charge. Because of the small size of hydrogen relative to other atoms and molecules, the resulting charge, though only partial, nevertheless represents a large charge density. A hydrogen bond results when this strong positive charge density attracts a [[lone pair]] of electrons on another heteroatom, which becomes the hydrogen-bond ''acceptor''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The hydrogen bond is not like a simple attraction between point charges, however. It possesses some degree of orientational preference, and can be shown to have some of the characteristics of a covalent bond. This covalency tends to be more extreme when acceptors bind hydrogens from more electronegative donors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Strong covalency in a hydrogen bond raises the questions: "To which molecule or atom does the hydrogen [[atomic nucleus|nucleus]] belong?" and "Which should be labelled 'donor' and which 'acceptor'? According to chemical convention, the donor generally is that atom to which, on separation of donor and acceptor, the retention of the hydrogen nucleus (or [[proton]]) would cause no increase in the atom's positive charge. The acceptor meanwhile is the atom or molecule that would become more positive by retaining the positively charged proton. Liquids that display hydrogen bonding are called '''associated liquids'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hydrogen bonds can vary in strength from very weak (1-2 kJ mol<sup>−1</sup>) to so strong (40 kJ mol<sup>−1</sup>) so as to be indistinguishable from a covalent bond, as in the ion HF<sub>2</sub><sup>−</sup>. The length of hydrogen bonds depends on bond strength, temperature and pressure. The typical length of a hydrogen bond in water is 1.97 Å. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Hydrogen bond in water === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The most ubiquitous, and perhaps simplest, example of a hydrogen bond is | ||

| + | found between [[water]] molecules. In a discrete water molecule, water has two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Two molecules of water can form a hydrogen bond between them. The oxygen of one water molecule has two lone pairs of electrons, each of which can form a hydrogen bond with hydrogens on two other water molecules. This can repeat so that every water molecule is H-bonded with four other molecules (two through its two lone pairs, and two through its two hydrogen atoms.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | :H-O-H<sup>...</sup>O-H<sub>2</sub> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Liquid]] water's high [[boiling point]] is due to the high number of hydrogen bonds each molecule can have relative to its low [[molecular mass]]. Water is unique because its oxygen atom has two lone pairs and two hydrogen atoms, meaning that the total number of bonds of a water molecule is four. (For example, hydrogen bromide- which has two lone pairs on the Br atom but only one H atom - can have a total of only two bonds.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | :H-Br<sup>...</sup>H-Br<sup>...</sup>H-Br | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[ice]], the crystalline lattice is dominated by a regular array of hydrogen bonds which space the water molecules farther apart than they are in liquid water. This accounts for water's decrease in density upon freezing. In other words, the presence of hydrogen bonds enables ice to float, because this spacing causes ice to be less dense than liquid water. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Were the bond strengths more equivalent, one might instead find the atoms of two interacting water molecules partitioned into two [[polyatomic ion]]s of opposite charge, specifically [[hydroxide]] and [[hydronium]].(Hydronium ions are also known as 'hydroxonium' ions). | ||

| + | |||

| + | :H-O<sup>−</sup> H<sub>3</sub>O<sup>+</sup> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Indeed, in pure water under conditions of [[standard temperature and pressure]], this latter formulation is applicable only rarely; on average about one in every 5.5 * 10<sup>8</sup> molecules gives up a proton to another water molecule, in accordance with the value of the [[dissociation constant]] for water under such conditions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Hydrogen bond in proteins === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hydrogen bonding also plays an important role in determining the three-dimensional structures adopted by proteins and nucleic acids. In these macromolecules, bonding between parts of the same macromolecule cause it to fold into a specific shape, which helps determine the molecule's physiological or biochemical role. The double helical structure of [[DNA]], for example, is due largely to hydrogen bonding between the [[base pair]]s, which link one complementary strand to the other and enable [[DNA replication|replication]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In proteins, hydrogen bonds form between the backbone oxygens and amide | ||

| + | hydrogens. When the spacing of the [[amino acid]] residues participating in | ||

| + | a hydrogen bond occurs regularly between positions ''i'' and ''i'' + 4, | ||

| + | an [[alpha helix]] is formed. When the spacing is less, between positions ''i'' | ||

| + | and ''i'' + 3, then a 3<sub>10</sub> helix is formed. When two strands are | ||

| + | joined by hydrogen bonds involving alternating residues on each | ||

| + | participating strand, a [[beta sheet]] is formed. (See also [[protein folding]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Dihydrogen bond === | ||

| + | {{main|Dihydrogen bond}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a very recent development, hydrogen bonds have been noted between two hydrogen atoms having opposite [[polarity]]. An example occurs in the molecule H<sub>3</sub>NBH<sub>3</sub> where the hydrogen atoms on nitrogen have a partial positive charge and the hydrogen atoms on boron have a partial negative charge. The resulting BH<sup>...</sup>HN attractions cause the molecule to be a solid material rather than a gas as is the case in the closely related substance, H<sub>3</sub>CCH<sub>3</sub>. Because two hydrogen atoms are involved, this is termed a dihydrogen bond. See references below (Crabtree, et al.). | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Symmetric hydrogen bond=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Symmetric hydrogen bonds]] have been observed recently spectroscopically in [[formic acid]] at high pressure (>GPa). Each hydrogen atom forms a partial covalent bond with two atoms rather than one. Symmetric hydrogen bonds have been postulated in ice at high pressure (ice-X). See references below (Goncharov, et al.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Advanced theory of the hydrogen bond === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The hydrogen bond remains a fairly mysterious object in the theoretical study of [[quantum field theory|quantum]] [[quantum chemistry|chemistry]] and [[physics]]. Most generally, the hydrogen bond can be viewed as a [[metric]] dependent [[electrostatic]] [[scalar field]] between two or more intermolecular bonds. This is slightly different than the [[intramolecular]] [[bound states]] of, for example, [[covalent bond|covalent]] or [[ionic bond]]s; however, hydrogen bonding is generally still a bound state phenomenon, since the [[interaction energy]] has a net negative sum. The question of the relationship between the covalent bond and the hydrogen bond remains largely unsettled, though the initial theory proposed by [[Linus Pauling]] suggests that the hydrogen bond has a partial covalent nature. While a lot of experimental data has been recovered for hydrogen bonds in [[water (molecule)|water]], for example, that provide good resolution on the scale of intermolecular distances and [[thermodynamics|molecular thermodynamics]], the [[kinetic theory|kinetic]] and [[nonlinear dynamics|dynamical]] properties of the hydrogen bond in [[dynamics (mechanics)|dynamical]] systems remains largely mysterious. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === References === | ||

| + | *A New Intermolecular Interaction: Unconventional Hydrogen Bonds with Element-Hydride Bonds as Proton Acceptor Robert H. Crabtree, Per E. M. Siegbahn, Odile Eisenstein, Arnold L. Rheingold, and Thomas F. Koetzle ''Acc. Chem. Res.'' '''1996''', ''29(7)'', 348 - 354. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Polymerization of Formic Acid under High Pressure Alexander F. Goncharov, M. Riad Manaa, Joseph M. Zaug, Richard H. Gee, Laurence E. Fried, and Wren B. Montgomery ''Phys. Rev. Lett.'' '''2005''', ''94'', 065505. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Chemistry]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Chemical bonding]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[ca:Pont d'hidrogen]] | ||

| + | [[de:Wasserstoffbrückenbindung]] | ||

| + | [[es:Enlace de hidrógeno]] | ||

| + | [[fr:Liaison hydrogène]] | ||

| + | [[it:Legame idrogeno]] | ||

| + | [[he:קשרי מימן]] | ||

| + | [[nl:Waterstofbrug]] | ||

| + | [[ja:水素結合]] | ||

| + | [[nn:Hydrogenbinding]] | ||

| + | [[pl:Wiązanie wodorowe]] | ||

| + | [[ru:Водородная связь]] | ||

| + | [[sv:Vätebindning]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Old end== | ||

The electrons in the MO of a bond are said to be either “localized” on certain atom(s) or “delocalized” between two or more atoms. The type of bond between two atoms is defined by how much the [[electron density]] is localized or delocalized among the atoms of the substance. | The electrons in the MO of a bond are said to be either “localized” on certain atom(s) or “delocalized” between two or more atoms. The type of bond between two atoms is defined by how much the [[electron density]] is localized or delocalized among the atoms of the substance. | ||

Revision as of 21:28, 15 October 2005

A chemical bond is the phenomenon of atoms being held together to form molecules or crystals. All chemical bonds result from electrostatic interactions and/or from sharing of electrons, and derive from the action of the electromagnetic force. Where the electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental interactions of the physical universe. Electrostatic forces arise from the coulombic attraction or repulson between charged particles. On the other hand the sharing of electrons is described by quantum mechanics in Valence bond theory and Molecular orbital theory.

There are 5 different classes of chemical bonds that we use to categorize bonding. Actual bonds may have have properties that aren't so discretely categorized, so a given bond could be defined by more than one of these terms.

The Ionic Bond

- Original article: ionic bond

An ionic bond can be formed after two or more atoms lose or gain electrons to form an ion. Ionic bonds occur between metals, losing electrons, and non-metals, gaining electrons. Ions with opposite charges will attract one another creating an ionic bond. Such bonds are stronger than hydrogen bonds, but similar in strength to covalent bonds.

It only occurs if the overall energy change for the reaction is favourable (the bonded atoms have a lower energy than the free ones). The larger the energy change the stronger the bond.

Pure ionic bonding doesn't actually happen with real atoms. All bonds have a small amount of covalency. The larger the difference in electronegativity the more ionic the bond.

| File:Ionic bonding.png | File:Ionicbond.JPG |

|

The diagram above shows the electron configurations of lithium and fluorine. Note that lithium has one electron in its outer shell. This electron is held rather loosely (because the ionisation energy is very different in the two ions). Note also that fluorine has 7 electrons in its outer shell. If the electron moves from lithium to fluorine each ion acquires the configuration of a noble gas. The bonding energy (from the electrostatic attraction of the two oppositely charged ions) is large enough (negative value) that the overall bonded state energy is lower than the unbonded state. |

Impression of two ions (for example [Na]+ and [Cl]-) forming an ionic bond. Electron orbitals generally do not overlap (ie. molecular orbitals are not formed), because each of the ions reached the lowest energy state, and the bond is based only (ideally) on the electrostatic interactions between positive and negative ions. |

Difference between ionic and covalent bonds

In an ionic bond, the atoms are bound by attraction of opposite ions, whereas in a covalent bond, atoms are bound by sharing electrons. In covalent bonding, the geometry around each atom is determined by VSEPR rules, whereas in ionic materials, the geometry follows maximum packing rules. Thus, a compound can be classified as ionic or covalent based on the geometry of the atoms.

Template:Chem-stub

de:Ionische Bindung et:Iooniline side es:Enlace iónico fr:Liaison ionique it:Legame ionico he:קשר יוני nl:Ionaire binding ja:イオン結合 nn:Ionebinding pt:Ligação iônica sl:Ionska vez fi:Ionisidos th:พันธะไอออน zh:离子键

The Covalent Bond

- Original article: covalent bond

Covalent bonding is a form of chemical bonding characterized by the sharing of one or more pairs of electrons between two elements, producing a mutual attraction that holds the resultant molecule together. Atoms tend to share electrons in such a way that their outer electron shells are filled. Such bonds are always stronger than the intermolecular hydrogen bond and similar in strength to or stronger than the ionic bond. While covalent bonding most often occurs between atoms, metals can form covalent bonds with other covalent bonds themselves which can complicate matters somewhat.

Covalent bonding most frequently occurs between atoms with similar electronegativities. For this reason, non-metals tend to engage in covalent bonding more readily since metals have access to metallic bonding, where the easily-removed electrons are freer to roam about. For non-metals, liberating an electron is more difficult, so sharing is the only option when confronted with another species of similar electronegativity.

However, covalent bonding in metals and, particularly between metals and organic compounds is particularly important, especially in industrial catalysis and process chemistry, where many indispensible reactions depend on covalent bonding with metals.

History

The idea of covalent bonding can be traced to Gilbert N. Lewis, who in 1916 described the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. He introduced the so called Lewis Notation or Electron Dot Notation in which valence electrons (those in the outer shell) are represented as dots around the atomic symbols. Pairs of electrons located between atoms represent covalent bonds. Multiple pairs represent multiple bonds, such as double and triple bonds. Some examples of Electron Dot Notation are shown in the following figure. An alternative form, in which bond-forming electron pairs are represented as solid lines, is shown in blue.

While the idea of shared electron pairs provides an effective qualitative picture of covalent bonding, quantum mechanics is needed to understand the nature of these bonds and predict the structures and properties of simple molecules. Heitler and London are credited with the first successful quantum mechanical explanation of a chemical bond, specifically that of molecular hydrogen, in 1927. Their work was based on the valence bond model, which assumes that a chemical bond is formed when there is good overlap between the atomic orbitals of participating atoms. These atomic orbitals are known to have specific angular relationships between each other, and thus the valence bond model can successfully predict the bond angles observed in simple molecules.

Bond order

Bond order is the scientific term used to describe the number of pairs of electrons shared between atoms forming a covalent bond. The most common type of covalent bond is the single bond, the sharing of only one pair of electrons between two individual atoms. All bonds with more than one shared pair are called multiple covalent bonds. The sharing of two pairs is called a double bond and the sharing of three pairs is called a triple bond. An example of a double bond is nitrous acid (between N and O), and an example of a triple bond is in hydrogen cyanide (between C and N).

A single bond usually consists of one sigma bond, a double bond of one sigma and one pi bond, and a triple bond of one sigma and two pi bonds.

Quadruple bonds, though rare, also exist. Both carbon and silicon can theoretically form these; however, the formed molecules are explosively unstable. Stable quadruple bonds are observed as transition metal-metal bonds, usually between two transition metal atoms in organometallic compounds. Molybdenum and Ruthenium are the elements most commonly observed with this bonding configuration. An example of a quadruple bond is also found in Di-tungsten tetra(hpp). Quintuple Bonds are found to exist in certain chromium dimers.

Sextuple bonds of order 6 have also been observed in transition metals in the gaseous phase at very low temperatures and are extremely rare.

Other more exotic bonds, such as three center bonds are known and defy the conventions of bond order. It is also important to note that bond order is an integer value only in the elementary sense and is often fractional in more advanced contexts.

Rigidity

Typically, two atoms can rotate about a single bond with relative ease. However, double and triple bonds are very difficult to rotate because they require pi orbital overlap. Pi orbital overlaps are parallel.

Resonance

Some structures can have more than one valid Lewis Dot Structure (for example, ozone, O3). In an LDS diagram of O3, the center atom will have a single bond with one atom and a double bond with the other. The LDS diagram cannot tell us which atom has the double bond; the first and second adjoining atoms have equal chances of having the double bond. These two possible structures are called resonance structures. In reality, the structure of ozone is a resonance hybrid between its two possible resonance structures. Instead of having one double bond and one single bond, there are actually two 1.5 bonds with approximately three electrons in each at all times.

A special resonance case is exhibited in aromatic rings of atoms (for example, benzene). Aromatic rings are composed of atoms arranged in a circle (held together by covalent bonds) that alternate between single and double bonds according to their LDS. In actuality, the electrons tend to be disambiguously and evenly spaced within the ring. Electron sharing in aromatic structures is often represented with a ring inside the circle of atoms.

Current theory

Today the valence bond model has been supplemented with the molecular orbital model. In this model, as atoms are brought together, the atomic orbitals interact to form hybrid molecular orbitals. These molecular orbitals are a cross between the original atomic orbitals and generally extend between the two bonding atoms.

Using quantum mechanics it is possible to calculate the electronic structure, energy levels, bond angles, bond distances, dipole moments, and frequency spectra of simple molecules with a high degree of accuracy. Currently, bond distances and angles can be calculated as accurately as they can be measured (distances to a few pm and bond angles to a few degrees). For the case small molecules, energy calculations are sufficiently accurate to be useful for determining thermodynamic heats of formation and kinetic activation energy barriers.

See also

- chemical bond

- ionic bond

- linear combination of atomic orbitals

- metallic bond

External links

ar:رابطة تساهمية bg:Ковалентна химична връзка ca:Enllaç covalent da:Kovalent de:Atombindung et:Kovalentne side es:Enlace covalente fa:پیوند کووالانسی fr:Liaison covalente he:קשר קוולנטי nl:Covalente binding ja:共有結合 nn:Kovalent binding pl:Wiązanie kowalencyjne pt:Ligação covalente fi:Kovalenttinen sidos sv:Kovalent bindning zh:共价键

Metallic Bond

The traditional picture of the metallic bond was developed soon after the discovery of the electron. In this picture the valence electrons were viewed as an electron-gas permeating the crystal lattice structre of the metal atoms. The cohesive forces holding the metal together could be qualitatively seen as resulting from the electrostatic interaction of the positively charged metal atom cores with the negatively charged electron-gas.

With the development of quantum mechanics this picture has changed significantly. Quantum mechanically covalent bonding can be described by constructing molecular orbitals from a linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO theory). For some molecules, such as benzene, which contain resonance in an extended conjugated system, some of the molecular orbitals are delocalized and the electrons not fixed between particular atoms. Applying these concepts to metals leads to the Band theory of solids. In this theory the metallic bond is similar to the delocalized molecular orbitals of benzene, but on a much larger scale and with the bonding spread throughout the metal.

Let us consider a sodium atom. It has one valence electron in an s orbital. When we add another atom the overlap of the two s orbitals results in two molecular orbitals of differing energies. Adding a third atom results in three molecular orbitals and so on. In a small lump of sodium there are many thousands of atoms and consequently many thousands of molecular orbitals whose energies lie close together, This results in an energy band populated by the available electrons that is called the s-band. Similarly, with other atoms, you can also get a p-band from the overlap of atomic p orbitals.

In semiconductors there is a significant energy difference between different bands called a band gap. This is what gives semiconductors their usefull properties exploited in electronic circuits.

Hydrogen Bond

- Original article: hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond is a type of attractive intermolecular force that exists between two partial electric charges of opposite polarity. Although stronger than most other intermolecular forces, the typical hydrogen bond is much weaker than both the ionic bond and the covalent bond. Within macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, it can exist between two parts of the same molecule, and figures as an important constraint on such molecules' overall shape.

As the name "hydrogen bond" implies, one part of the bond involves a hydrogen atom. The hydrogen must be attached to a strongly electronegative heteroatom, such as oxygen, nitrogen or fluorine, which is called the hydrogen-bond donor. This electronegative element attracts the electron cloud from around the hydrogen nucleus and, by decentralizing the cloud, leaves the atom with a positive partial charge. Because of the small size of hydrogen relative to other atoms and molecules, the resulting charge, though only partial, nevertheless represents a large charge density. A hydrogen bond results when this strong positive charge density attracts a lone pair of electrons on another heteroatom, which becomes the hydrogen-bond acceptor.

The hydrogen bond is not like a simple attraction between point charges, however. It possesses some degree of orientational preference, and can be shown to have some of the characteristics of a covalent bond. This covalency tends to be more extreme when acceptors bind hydrogens from more electronegative donors.

Strong covalency in a hydrogen bond raises the questions: "To which molecule or atom does the hydrogen nucleus belong?" and "Which should be labelled 'donor' and which 'acceptor'? According to chemical convention, the donor generally is that atom to which, on separation of donor and acceptor, the retention of the hydrogen nucleus (or proton) would cause no increase in the atom's positive charge. The acceptor meanwhile is the atom or molecule that would become more positive by retaining the positively charged proton. Liquids that display hydrogen bonding are called associated liquids.

Hydrogen bonds can vary in strength from very weak (1-2 kJ mol−1) to so strong (40 kJ mol−1) so as to be indistinguishable from a covalent bond, as in the ion HF2−. The length of hydrogen bonds depends on bond strength, temperature and pressure. The typical length of a hydrogen bond in water is 1.97 Å.

Hydrogen bond in water

The most ubiquitous, and perhaps simplest, example of a hydrogen bond is found between water molecules. In a discrete water molecule, water has two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Two molecules of water can form a hydrogen bond between them. The oxygen of one water molecule has two lone pairs of electrons, each of which can form a hydrogen bond with hydrogens on two other water molecules. This can repeat so that every water molecule is H-bonded with four other molecules (two through its two lone pairs, and two through its two hydrogen atoms.)

- H-O-H...O-H2

Liquid water's high boiling point is due to the high number of hydrogen bonds each molecule can have relative to its low molecular mass. Water is unique because its oxygen atom has two lone pairs and two hydrogen atoms, meaning that the total number of bonds of a water molecule is four. (For example, hydrogen bromide- which has two lone pairs on the Br atom but only one H atom - can have a total of only two bonds.)

- H-Br...H-Br...H-Br

In ice, the crystalline lattice is dominated by a regular array of hydrogen bonds which space the water molecules farther apart than they are in liquid water. This accounts for water's decrease in density upon freezing. In other words, the presence of hydrogen bonds enables ice to float, because this spacing causes ice to be less dense than liquid water.

Were the bond strengths more equivalent, one might instead find the atoms of two interacting water molecules partitioned into two polyatomic ions of opposite charge, specifically hydroxide and hydronium.(Hydronium ions are also known as 'hydroxonium' ions).

- H-O− H3O+

Indeed, in pure water under conditions of standard temperature and pressure, this latter formulation is applicable only rarely; on average about one in every 5.5 * 108 molecules gives up a proton to another water molecule, in accordance with the value of the dissociation constant for water under such conditions.

Hydrogen bond in proteins

Hydrogen bonding also plays an important role in determining the three-dimensional structures adopted by proteins and nucleic acids. In these macromolecules, bonding between parts of the same macromolecule cause it to fold into a specific shape, which helps determine the molecule's physiological or biochemical role. The double helical structure of DNA, for example, is due largely to hydrogen bonding between the base pairs, which link one complementary strand to the other and enable replication.

In proteins, hydrogen bonds form between the backbone oxygens and amide hydrogens. When the spacing of the amino acid residues participating in a hydrogen bond occurs regularly between positions i and i + 4, an alpha helix is formed. When the spacing is less, between positions i and i + 3, then a 310 helix is formed. When two strands are joined by hydrogen bonds involving alternating residues on each participating strand, a beta sheet is formed. (See also protein folding).

Dihydrogen bond

In a very recent development, hydrogen bonds have been noted between two hydrogen atoms having opposite polarity. An example occurs in the molecule H3NBH3 where the hydrogen atoms on nitrogen have a partial positive charge and the hydrogen atoms on boron have a partial negative charge. The resulting BH...HN attractions cause the molecule to be a solid material rather than a gas as is the case in the closely related substance, H3CCH3. Because two hydrogen atoms are involved, this is termed a dihydrogen bond. See references below (Crabtree, et al.).

Symmetric hydrogen bond

Symmetric hydrogen bonds have been observed recently spectroscopically in formic acid at high pressure (>GPa). Each hydrogen atom forms a partial covalent bond with two atoms rather than one. Symmetric hydrogen bonds have been postulated in ice at high pressure (ice-X). See references below (Goncharov, et al.)

Advanced theory of the hydrogen bond

The hydrogen bond remains a fairly mysterious object in the theoretical study of quantum chemistry and physics. Most generally, the hydrogen bond can be viewed as a metric dependent electrostatic scalar field between two or more intermolecular bonds. This is slightly different than the intramolecular bound states of, for example, covalent or ionic bonds; however, hydrogen bonding is generally still a bound state phenomenon, since the interaction energy has a net negative sum. The question of the relationship between the covalent bond and the hydrogen bond remains largely unsettled, though the initial theory proposed by Linus Pauling suggests that the hydrogen bond has a partial covalent nature. While a lot of experimental data has been recovered for hydrogen bonds in water, for example, that provide good resolution on the scale of intermolecular distances and molecular thermodynamics, the kinetic and dynamical properties of the hydrogen bond in dynamical systems remains largely mysterious.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- A New Intermolecular Interaction: Unconventional Hydrogen Bonds with Element-Hydride Bonds as Proton Acceptor Robert H. Crabtree, Per E. M. Siegbahn, Odile Eisenstein, Arnold L. Rheingold, and Thomas F. Koetzle Acc. Chem. Res. 1996, 29(7), 348 - 354.

- Polymerization of Formic Acid under High Pressure Alexander F. Goncharov, M. Riad Manaa, Joseph M. Zaug, Richard H. Gee, Laurence E. Fried, and Wren B. Montgomery Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 065505.

ca:Pont d'hidrogen de:Wasserstoffbrückenbindung es:Enlace de hidrógeno fr:Liaison hydrogène it:Legame idrogeno he:קשרי מימן nl:Waterstofbrug ja:水素結合 nn:Hydrogenbinding pl:Wiązanie wodorowe ru:Водородная связь sv:Vätebindning

Old end

The electrons in the MO of a bond are said to be either “localized” on certain atom(s) or “delocalized” between two or more atoms. The type of bond between two atoms is defined by how much the electron density is localized or delocalized among the atoms of the substance.

Many simple compounds involve covalent bonds. These molecules have structures that can be predicted using valence bond theory, and the properties of atoms involved can be understood using concepts such as oxidation number. Other compounds that involve ionic structures can be understood using theories from classical physics. However, more complicated compounds such as metal complexes cannot be described by valence bond theory, and we need quantum chemistry (based on quantum mechanics) to help us understand these molecules.

In the case of ionic bonding, electrons are mainly localized on the individual atoms, and electrons do not travel between the atoms very much. Each atom is assigned an overall electric charge to help us conceptualize the MO's distribution. The forces between atoms (or ions) are largely characterized by isotropic continuum electrostatic potentials.

By contrast, in covalent bonding, the electron density within bonds is not assigned to individual atoms, but is instead delocalized in the MOs between atoms. The widely-accepted theory of the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) helps describe the MOs' structures and energies based on the AOs of the atoms they came from. Unlike pure ionic bonds, covalent bonds may have directed anisotropic properties.

Atoms can also form bonds that are intermediates between ionic and covalent. This is because these definitions are based on the extent of electron delocalization. Electrons can be partially delocalized between atoms, but spend more time around one atom than another. This type of bond is often called “polar covalent”.

These chemical bonds are intramolecular forces that keep atoms held together in molecules. There are also intermolecular forces that cause molecules to be attracted or repulsed by each other. These forces include ionic interactions, hydrogen bonds, dipole-dipole interactions, and induced dipole interactions.

Linus Pauling's book The Nature of the Chemical Bond is perhaps the most influential book on chemistry ever published.

References

- W. Locke (1997). Introduction to Molecular Orbital Theory. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

- Carl R. Nave (2005). HyperPhysics. Retrieved May 18, 2005.

| ||||||||

| General subfields within the Natural sciences |

|---|

| Astronomy | Biology | Chemistry | Earth science | Ecology | Physics |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.