Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Book of Acts" - New World

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

Philip converts an Ethopian eunuch, the first Gentile offical to join the new faith. | Philip converts an Ethopian eunuch, the first Gentile offical to join the new faith. | ||

| − | ===Paul's | + | ===Paul's conversion=== |

Paul of Tarsus, also known as Saul, is the main character of the second half of Acts, which deals with the work of the Holy Spirit as it moves beyond Judea and begins to bring large numbers of Gentiles into faith in the [[Gospel]]. In one of the [[New Testament]]'s most dramatic episodes, Paul travels on the road to Damascus, where he intends to arrest Jews who profess faith in Jesus. "Suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground" (9:3-4) and Paul becomes blind for three days (9:9). In a later account Paul hears a voice saying: "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? ... I am Jesus" (26:14-15). In Damascus, Paul is cured from his blindness and becomes as ardent believer. However, the Jerusalem community is suspicious and fearful of him at first, but he wins the apostles' trust and faces danger from the Hellenistic Jews whom he debates. After this the church in Judea, Galilee, and Samaria enjoys a period of growth and relative peace. (9:31) | Paul of Tarsus, also known as Saul, is the main character of the second half of Acts, which deals with the work of the Holy Spirit as it moves beyond Judea and begins to bring large numbers of Gentiles into faith in the [[Gospel]]. In one of the [[New Testament]]'s most dramatic episodes, Paul travels on the road to Damascus, where he intends to arrest Jews who profess faith in Jesus. "Suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground" (9:3-4) and Paul becomes blind for three days (9:9). In a later account Paul hears a voice saying: "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? ... I am Jesus" (26:14-15). In Damascus, Paul is cured from his blindness and becomes as ardent believer. However, the Jerusalem community is suspicious and fearful of him at first, but he wins the apostles' trust and faces danger from the Hellenistic Jews whom he debates. After this the church in Judea, Galilee, and Samaria enjoys a period of growth and relative peace. (9:31) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Gentile converts=== | ||

Peter, meanwhile, conducts several miraculous healings, including the raising of the female disciple, Tabitha, from the dead (9:40). During Peter's travels a Roman centurion named Cornelius receives a revelation from an [[angel]] that he must meet Peter. Cornelius sends to invite Peter to dine with him. Peter himself, meanwhile, has a dream in which God commands him to eat non-[[kosher]] food, which Peter has never done previously. The next day, Peter eats at Cornelius' home and preaches there. Several Gentiles are converted, and Peter batpizes them.<ref>The fact that these men are baptized into the faith without first being circumcized is significant in showing that not only Paul, but Peter, too, practiced this tradition.</ref> Back in Jerusalem, Peter is criticized by the "cirumcized believers" for enter a Gentile home and eating with non-Jews. His critics are silenced, however, when Peter relates the above events.<ref>Many scholars believe these chapters are related to the incident in Galatians 3 in which Paul criticizes Peter for refusing to eat with Gentiles, seeing a tendency in Luke to play down the any tension between the Pauline tradition and that of Peter or the Jerusalem church</ref> | Peter, meanwhile, conducts several miraculous healings, including the raising of the female disciple, Tabitha, from the dead (9:40). During Peter's travels a Roman centurion named Cornelius receives a revelation from an [[angel]] that he must meet Peter. Cornelius sends to invite Peter to dine with him. Peter himself, meanwhile, has a dream in which God commands him to eat non-[[kosher]] food, which Peter has never done previously. The next day, Peter eats at Cornelius' home and preaches there. Several Gentiles are converted, and Peter batpizes them.<ref>The fact that these men are baptized into the faith without first being circumcized is significant in showing that not only Paul, but Peter, too, practiced this tradition.</ref> Back in Jerusalem, Peter is criticized by the "cirumcized believers" for enter a Gentile home and eating with non-Jews. His critics are silenced, however, when Peter relates the above events.<ref>Many scholars believe these chapters are related to the incident in Galatians 3 in which Paul criticizes Peter for refusing to eat with Gentiles, seeing a tendency in Luke to play down the any tension between the Pauline tradition and that of Peter or the Jerusalem church</ref> | ||

| − | Meanwhile a sizeable community of Gentile believers has grown in Syrian Antioch. The Jerusalem church send Barnabas, a [[Levite]], to minister to them.<ref>As a Levite, Barnabas would be particularly knowledgable about Jewish tradition. He is thus and interesting choice as Jerusalem's representative to the first Gentile Christian community.</ref>Barnabas finds Paul in Tarsus and brings him to Antioch as well. It is here that the followers of Jesus are first called Christians. Christian prophets, one of whom is named Agabus, come to Antioch from [[Jerusalem]] and predict to the Aniochans that a famine will soon spread across the Roman world. A collection is taken up to send aid to the Judean church. Interestingly, no mention is made of the visit from Peter to Antioch, mentioned by Paul in Galatians 3 <ref>Some have suggested that these prophets may be the "men from James" with whom Paul has such difficulty. Galatians 3 also reveals a split between Peter and Paul, with Peter refusing to eat with Gentiles and Paul publicly condemning him for this. In the argument, Barnabas, the Levite, sides with Peter. That such an event could have happened after Peter's supposed revelation from God is highly doubtly, leaving many to question whether the episode of Acts 10-11 is out of chronological order, or perhaps even fictional.</ref> | + | Meanwhile a sizeable community of Gentile believers has grown in Syrian Antioch. The Jerusalem church send Barnabas, a [[Levite]], to minister to them.<ref>As a Levite, Barnabas would be particularly knowledgable about Jewish tradition. He is thus and interesting choice as Jerusalem's representative to the first Gentile Christian community.</ref>Barnabas finds Paul in Tarsus and brings him to Antioch as well. It is here that the followers of Jesus are first called Christians. Christian prophets, one of whom is named Agabus, come to Antioch from [[Jerusalem]] and predict to the Aniochans that a famine will soon spread across the Roman world. A collection is taken up to send aid to the Judean church. Interestingly, no mention is made of the visit from Peter to Antioch, mentioned by Paul in Galatians 3 <ref>Some have suggested that these prophets may be the "men from James" with whom Paul has such difficulty. Galatians 3 also reveals a split between Peter and Paul, with Peter refusing to eat with Gentiles and Paul publicly condemning him for this. In the argument, Barnabas, the Levite, sides with Peter. That such an event could have happened after Peter's supposed revelation from God is highly doubtly, leaving many to question whether the episode of Acts 10-11 is out of chronological order, or perhaps even fictional.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Peter, meanwhile, is imprisoned by King [[Herod Agrippa]], but miraculously escapes. | ||

Several years later, [[Barnabas]] and Paul set out on a mission (13-14) to further spread Christianity, particularly among the Gentiles. Paul travels through [[Asia Minor]], preaching and visiting churches throughout the region. Paul then travels to Jerusalem where he meets with the apostles—a meeting known as the [[Council of Jerusalem]] (15). Paul's own record of the meeting appears in (Gal.2}. <ref>However, the account differs significantly from Acts, and some argue Gal 2 is a different meeting.</ref> Some members of the [[Jerusalem church]] have been preaching that [[circumcision]] is required for Gentiles who join the faith. Paul and his associates strongly disagree. After much discussion, [[James]], the brother of Jesus, leader of the Jerusalem church, decrees that Gentile members need not follow all of the [[Mosaic Law]], and in particular, they do not need to be circumcised. | Several years later, [[Barnabas]] and Paul set out on a mission (13-14) to further spread Christianity, particularly among the Gentiles. Paul travels through [[Asia Minor]], preaching and visiting churches throughout the region. Paul then travels to Jerusalem where he meets with the apostles—a meeting known as the [[Council of Jerusalem]] (15). Paul's own record of the meeting appears in (Gal.2}. <ref>However, the account differs significantly from Acts, and some argue Gal 2 is a different meeting.</ref> Some members of the [[Jerusalem church]] have been preaching that [[circumcision]] is required for Gentiles who join the faith. Paul and his associates strongly disagree. After much discussion, [[James]], the brother of Jesus, leader of the Jerusalem church, decrees that Gentile members need not follow all of the [[Mosaic Law]], and in particular, they do not need to be circumcised. | ||

Revision as of 00:51, 31 July 2007

| New Testament |

|---|

The Acts of the Apostles is a book of the Bible, which now stands fifth in the New Testament. It is commonly referred to as simply Acts. The title "Acts of the Apostles" (Greek Praxeis Apostolon) was first used by Irenaeus in the late second century, but some have suggested that the title "Acts" be interpreted as the "Acts of the Holy Spirit" or even the "Acts of Jesus," since 1:1 gives the impression that Acts is set forth as 'an account of what Jesus continued to do and teach', Christ himself being the principal actor.[1]

Acts tells the story of the Early Christian church, with particular emphasis on the ministry of the Twelve Apostles and of Paul of Tarsus. The early chapters, set in Jerusalem, discuss Jesus's Resurrection, his Ascension, the Day of Pentecost, and the start of the Twelve Apostles' ministry. The later chapters discuss Paul's conversion, his ministry, and finally his arrest and imprisonment and trip to Rome.

It is almost universally agreed that the author of Acts also wrote the Gospel of Luke. The traditional view is that both the two books were written c. 60 by a companion of Paul named Luke — a view which is still held by some scholars, though some view the books as having been written by an unknown author at a later date, sometime between 70 and 100.

Content

|

|

Summary

The author begins with a prologue addressed to a person named Theophilius and references "my earlier book"—almost certainly the Gospel of Luke. This is immediately followed by a narrative in which the the resurrected Jesus instructs the disciples to remain in Jerusalem to await the gift of the Holy Spirit. They ask him if he intends now to "restore the kingdom to Israel," a reference to his mission as the Jewish Messiah, but Jesus replies that the timing of such things is not for them to know. (1:6-7) After this, Jesus asends into a cloud and disappears. Too "men" appear and ask why they look to the sky, since Jesus will return in the same way he went.[2]

The Jerusalem church

The apostles, along with other of Jesus' mother, his brothers,[3] and other followers meet and elect Matthias to replace Judas Iscariot as a member of The Twelve. On Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descends on them. The apostles hear a great wind and witness "tongues of flames" descending on them, paralleling Luke 3:16-17. Thereafter, the apostles have the miraculous power to "speak in tongues" and when they address a crowd, each member of the crowd hears their speech in his own native language. Three thousand people reportedly become believers and are baptized as a result of this miracle (2:1-40).

Peter, along with John, preaches to many in Jerusalem, and perform miracles such as healings, the casting out of evil spirits, and the raising of the dead (ch. 3).

A controversy arises due to Peter and John preaching that Jesus had been raised from the dead. Sadduceean priests—who, unlike the Pharisees, denied the doctrine of the resurrection—have the two apostles arrested. The High Priest Annas, together with other Sadduceean leaders, question the two but fear punishing them on account of their having recently healed a man in the Temple precincts. Having earlier condemned Jesus to the Romans, they command the apostles not to speak in Jesus' name, but the apostles make it clear they do not intend to comply (4:1-21)

The growing community of Jewish Christians practices a form of communism: "selling their possessions and goods, they gave to anyone as he had need." (1:45) The policy is strictly enforced, and when one member, Ananias, withholds for himself part of the proceeds of a house he has sold, he and his wife are both slain by the Holy Spirit after hiding the fact from Peter. (5:1-20)

As their numbers increase, the believers begin to be increasingly persecuted. Once again the Sadducees move against them. Some of the apostles are arrested and flogged, but ultimately freed. The Pharisaic leader Gamaliel, however, defends them, warning his fellow members of the Sanhedrin to "Leave these men alone! Let them go! For if their purpose or activity is of human origin, it will fail. But if it is from God, you will not be able to stop these men; you will only find yourselves fighting against God." (5:38-39) Although they are flogged for disobeying the High Priest's earlier order, the disciples are freed and continue to preach open in the Temple courtyards.

An internal controversy arises within the Jerusalem church between the Judean and Hellenistic Jews[4], the latter alleging that their widows were being neglected. The Twelve, not wishing to oversee the distrubtions themselves, appointed Stephen and six others for this purpose so that the apostles themselves could concentrate on preaching (6:1-7) Many in Jerusalem join the faith, include "a large number of priests."

Although the apostles themselves manage to stay out of trouble, Stephen soon finds himself embroiled in a major controversy with other Hellenistic Jews, who accusing him of blasphemy. At his trial, Stephen gives an long, eloquent summary of providential history, but concludes by accusing those present of resisting the Holy Spirit, killing the prophets, and murdering the Messiah. This time, no one steps forward to defend the accused, and Stephen is immediately stoned to death, become the first Christian martyr.(ch. 6-7) One of those present at and approving of his death is Saul and Taursus, the future Saint Paul.

As a result of Stephen's confrontation with the Temple authorities, a widespread persecution breaks out against those Jews who affirm Jesus as Messiah. Many believers flee Jerusalem to the outlying areas of Judea and Samaria, although the apostles remain in Jerusalem. Saul is authorized by the High Priest to arrest believers and put them in prison.

The faith spreads

In Samaria, a disiple named Philip[5] performs miracles and influences many to believe. One of the new believers is Simon Magus, himself a miracle worker with a great reputation among the Samaritans. Peter and John soon arrive in order to impart the gift of the Holy Spirit to the newly baptized. Simon Magus is amazed at this and offers the apostles money that he too may learn to perform this great miracle. Peter takes offense at this, declaring, "may you money perish with you." Simon immediately repents and asks Peter to pray to God on his behalf. The apostles continue their journey among the Samaritans and many believe.[6]

Philip converts an Ethopian eunuch, the first Gentile offical to join the new faith.

Paul's conversion

Paul of Tarsus, also known as Saul, is the main character of the second half of Acts, which deals with the work of the Holy Spirit as it moves beyond Judea and begins to bring large numbers of Gentiles into faith in the Gospel. In one of the New Testament's most dramatic episodes, Paul travels on the road to Damascus, where he intends to arrest Jews who profess faith in Jesus. "Suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground" (9:3-4) and Paul becomes blind for three days (9:9). In a later account Paul hears a voice saying: "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? ... I am Jesus" (26:14-15). In Damascus, Paul is cured from his blindness and becomes as ardent believer. However, the Jerusalem community is suspicious and fearful of him at first, but he wins the apostles' trust and faces danger from the Hellenistic Jews whom he debates. After this the church in Judea, Galilee, and Samaria enjoys a period of growth and relative peace. (9:31)

Gentile converts

Peter, meanwhile, conducts several miraculous healings, including the raising of the female disciple, Tabitha, from the dead (9:40). During Peter's travels a Roman centurion named Cornelius receives a revelation from an angel that he must meet Peter. Cornelius sends to invite Peter to dine with him. Peter himself, meanwhile, has a dream in which God commands him to eat non-kosher food, which Peter has never done previously. The next day, Peter eats at Cornelius' home and preaches there. Several Gentiles are converted, and Peter batpizes them.[7] Back in Jerusalem, Peter is criticized by the "cirumcized believers" for enter a Gentile home and eating with non-Jews. His critics are silenced, however, when Peter relates the above events.[8]

Meanwhile a sizeable community of Gentile believers has grown in Syrian Antioch. The Jerusalem church send Barnabas, a Levite, to minister to them.[9]Barnabas finds Paul in Tarsus and brings him to Antioch as well. It is here that the followers of Jesus are first called Christians. Christian prophets, one of whom is named Agabus, come to Antioch from Jerusalem and predict to the Aniochans that a famine will soon spread across the Roman world. A collection is taken up to send aid to the Judean church. Interestingly, no mention is made of the visit from Peter to Antioch, mentioned by Paul in Galatians 3 [10]

Peter, meanwhile, is imprisoned by King Herod Agrippa, but miraculously escapes.

Several years later, Barnabas and Paul set out on a mission (13-14) to further spread Christianity, particularly among the Gentiles. Paul travels through Asia Minor, preaching and visiting churches throughout the region. Paul then travels to Jerusalem where he meets with the apostles—a meeting known as the Council of Jerusalem (15). Paul's own record of the meeting appears in (Gal.2}. [11] Some members of the Jerusalem church have been preaching that circumcision is required for Gentiles who join the faith. Paul and his associates strongly disagree. After much discussion, James, the brother of Jesus, leader of the Jerusalem church, decrees that Gentile members need not follow all of the Mosaic Law, and in particular, they do not need to be circumcised.

Paul spends the next few years traveling through western Asia Minor and founds his first Christian church in Philippi. He then travels to Thessalonica, where he stays for some time before departing for Greece. In Athens, Paul visits an altar with an inscription dedicated to the Unknown God, so when he gives his speech on the Areopagos, he proclaims to worship that same Unknown God whom he identifies as the Christian God. During these travels, Paul collects funds for a major donation he intends to bring to Jersualem. His return is delayed by shipwrecks and close calls with the authorities, but finally he lands in Haifa.

Upon Paul's arrival in Jerusalem, he is met by James who confronts him with the rumor of that he is teaching against the Law of Moses (21:21), telling even Jews that they must refain from circumcising their sons. To prove that he himself is "living in obedience to the law," Paul accompanies some fellow Jewish Christians to complete a vow at the Temple (21:26). Near the end of the seven days of the vow, Paul is recognized and nearly beaten to death by a mob, accused of the sin of bringing Gentiles into the Temple confines. (21:28). Paul is rescued by a Roman commander.

but is imprisoned in Caesarea (23–26). Paul asserts his right, as a Roman citizen, to be tried in Rome. Paul is sent by sea to Rome, where he spends another two years under house arrest, proclaiming the Kingdom of God and teaching the "Lord Jesus Christ" (28:30-31). Surprisingly, Acts does not record the outcome of Paul's legal troubles — some traditions hold that Paul was ultimately executed in Rome, while other traditions have him surviving the encounter and later traveling to Spain and Great Britain — see Paul - Imprisonment & Death.

Themes and style

- Universality of Christianity

One of the central themes of Acts, indeed of the New Testament, see also Great Commission, is the universality of Christianity — the idea that Jesus's teachings were for all humanity — Jews and Gentiles alike. In this view, Christianity is seen as a religion in its own right, rather than a subset of Judaism, if one makes the common assumption that Judaism is not universal, however see Noahide Laws and Judaism and Christianity for details. Whereas the members of Jewish Christianity were circumcised and adhered to dietary laws, the Pauline Christianity featured in Acts did not require Gentiles to be circumcised or to obey all of the Mosaic laws, which is consistent with Noahide Law. The final chapter of Acts ends with Paul condemning non-Christian Jews and saying "Therefore I want you to know that God's salvation has been sent to the Gentiles, and they will listen!" (28:28). See also New Covenant (theology).

- Holy Spirit

As in the Gospel of Luke, there are numerous references to the Holy Spirit throughout Acts. Acts features the "baptism in the Holy Spirit" on Pentecost[12] and the subsequent spirit-inspired speaking in tongues. The Holy Spirit is shown guiding the decisions and actions of Christian leaders[13], and the Holy Spirit is said to "fill" the apostles, especially when they preach.[14] As a result, Acts is particularly influential among branches of Christianity which place particular emphasis the Holy Spirit, such as Pentecostalism and the Charismatic movement.

- Attention to the oppressed and persecuted

The Gospel of Luke and Acts both devote a great deal of attention to the oppressed and downtrodden. The impovershed are generally praised[15], while the wealthy are criticized. Luke-Acts devotes a great deal of attention to women in general[16] and to widows in particular.[17] The Samaritans of Samaria (see map at Iudaea Province), had their temple on Mount Gerizim, and along with some other differences, see Samaritanism, were in conflict with Jews of Judea and Galilee and other regions who had their Temple in Jerusalem and practiced Judaism. Unexpectedly, since Jesus was a Jewish Galilean, the Samaritans are shown favorably in Luke-Acts.[18] In Acts, attention is given to the religious persecution of the early Christians, as in the case of Stephen's martyrdom and the numerous examples are Paul's persecution for his preaching of Christianity.

- Prayer

Prayer is a major motif in both the Gospel of Luke and Acts. Both books have a more prominent attention to prayer than is found in the other gospels.[19] The Gospel of Luke depicts prayer as a certain feature in Jesus's life. Examples of prayer which are unique to Luke include Jesus's prayers at the time of his baptism (Luke 3:21), his praying all night before choosing the twelve (Luke 6:12), and praying for the transfiguration (Luke 9:28). Acts also features an emphasis on prayer and includes a number of notable prayers such as the Believers' Prayer (4:23-31), Stephen's death prayer (7:59-60), and Simon Magus' prayer (8:24). See also Prayer in the New Testament.

- Speeches

Acts features a number of extended speeches or sermons from Peter, Paul, and others. In fact, there are at least 24 different speeches in Acts, and the speeches comprise about 30% of the total verses.[20] These speeches, which are quoted verbatim at length rather than simply summarized, have been the source of debates over the historical accuracy of Acts. (see below).

Authorship

While the precise identity of the author is debated, the general consensus is that the author was a Greek Gentile writing for an audience of Gentile Christians.

Common authorship of Luke and Acts

There is substantial evidence to indicate that the author of The Gospel of Luke also wrote the Book of Acts. The most direct evidence comes from the prefaces of each book. Both prefaces are addressed to Theophilus, the author's patron—and perhaps a label for a Christian community as a whole as the name means "Beloved by God." Furthermore, the preface of Acts explicitly references "my former book" about the life of Jesus—almost certainly the work we know as The Gospel of Luke.

Furthermore, there are linguistic and theological similarities between the Luke and Acts. As one scholar writes,"the extensive linguistic and theological agreements and cross-references between the Gospel of Luke and the Acts indicate that both works derive from the same author"[21] Because of their common authorship, the Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles are often jointly referred to simply as Luke-Acts. Similarly, the author of Luke-Acts is often known as "Luke"—even among scholars who doubt that the author was actually named Luke.

Luke the physician as author

The traditional view is that the Gospel of Luke and Acts were written by the physician Luke, a companion of Paul. This Luke is mentioned in Paul's Epistle to Philemon (v.24), and in two other epistles which are traditionally ascribed to Paul (Colossians 4:14 and 2 Timothy 4:11).

The view that Luke-Acts was written by the physician Luke was nearly unanimous in the early Christian church. The Papyrus Bodmer XIV, which is the oldest known manuscript containing the start of the gospel (dating to around 200 C.E.), uses the title "The Gospel According to Luke." Nearly all ancient sources also shared this theory of authorship—Irenaeus,[22] Tertullian,[23] Clement of Alexandria,[24] Origen, and the Muratorian Canon all regarded Luke as the author of the Luke-Acts. Neither Eusebius of Caesarea nor any other ancient writer mentions another tradition about authorship.

In addition to the authorship evidence provided by the ancient sources, some feel the text of Luke-Acts supports the conclusion that its author was a companion of Paul. First among such internal evidence are portions of the book which have come to be called the "'we' passages." Although the bulk of Acts is written in the third person, several brief sections of the book are written from a first-person perspective.[25] These "we" sections are written from the point of view of a traveling companion of Paul: e.g. "After Paul had seen the vision, we got ready at once to leave for Macedonia," "We put out to sea and sailed straight for Samothrace"[26] Such passages would appear to have been written by someone who traveled with Paul during some portions of his ministry. Accordingly, some have used this evidence to support the conclusion that these passages, and therefore the entire text of the Luke-Acts, were written by a traveling companion of Paul's. The physician Luke would be one such person.

It has also been argued that level of detail used in the narrative describing Paul's travels suggests an eyewitness source. Some claim that the vocabulary used in Luke-Acts suggests its author may have had medical training, but this claim has been widely disputed.

An anonymous, non-eyewitness author

Some scholars have expressed doubt that the author of Luke-Acts was the physician Luke.[citation needed] Instead, they believe Luke-Acts was written by an anonymous Christian author who may not have been an eyewitness to any of the events recorded within the text.

Some of the evidence cited in favor of this opinion comes from the text of Luke-Acts itself. In the preface to Luke, the author refers to having eyewitness testimony "handed down to us" and to having undertaken a "careful investigation," but the author does not mention his own name or explicitly claim to be an eyewitness to any of the events.[citation needed] Except for the "we" passages in Acts, the narrative of Luke-Acts is written in the third person — the author never refers to himself as "I" or "me." To those who are skeptical of an eyewitness author, the "we passages" are usually regarded as fragments of a second document, part of some earlier account, which was later incorporated into Acts by the later author of Luke-Acts. An alternate theory is that the use of "we" was a stylistic idiosyncrasy used in many sea travel narratives written around the same time as Acts.[27]

Scholars also point to a number of apparent theological and factual discrepancies between Luke-Acts and Paul's letters. For example, Acts and the Pauline letters appear to disagree about the number and timings of Paul's visits to Jerusalem, and Paul's own account of his conversion is slightly different from the account given in Acts. Similarly, some believe the theology of Luke-Acts is slightly different from the theology espoused by Paul in his letters. This would suggest that the author of Luke-Acts did not have direct contact with Paul, but instead may have relied upon other sources for his portrayal of Paul.

Genre

The word "Acts" (Greek praxeis) denoted a recognized genre in the ancient world, "characterizing books that described great deeds of people or of cities."[28] There are several such books in the New Testament apocrypha, including the Acts of Thomas, the Acts of Andrew, and the Acts of John.

Modern scholars assign a wide range of genres to the Acts of the Apostles, including biography, novel and epic. Most, however, interpret it as history.[29]

Sources

The author of Acts likely relied upon other sources, as well as oral tradition, in constructing his account of the early church and Paul's ministry. Evidence of this is found in the prologue to the Gospel of Luke, where the author alluded to his sources by writing, "Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word." Some theorize that the "we" passages in Acts are one such "handed down" quotation from some earlier source who was a part of Paul's travels.

It is generally believed that the author of Acts did not have access to a collection of Paul's letters. One piece of evidence suggesting this is that although half of Acts centers on Paul, Acts never directly quotes from the epistles nor does it even mention Paul writing letters. Additionally, the epistles and Acts disagree about the general chronology of much of Paul's career. Since many of Paul's epistles are believed to be authentic, the discrepancies between the authentic epistles and Acts are probably errors on the part of Acts which were made because its author lacked access to the Pauline epistles or a similar source.

Other theories about Acts' sources are more controversial. Some historians believe that Acts borrows phraseology and plot elements from Euripides' play The Bacchae.[30] Some feel that the text of Acts shows evidence of having used the Jewish historian Josephus as a source (in which case it would to have been written sometime after 94 C.E.).[31]

Historical

The question of authorship is largely bound up with that as to the historicity of the contents. Conservative scholars view the book of Acts as being extremely accurate while skeptics view the work as being inaccurate. For example, the conservative Oxford scholar A.N. Sherwin-White wrote in his work Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament the following: "For the New Testament of Acts, the confirmation of historicity is overwhelming…any attempt to reject its basic historicity, even in matters of detail, must now appear absurd. Roman historians have long taken it for granted."[32] In addition, conservative scholars see the book of Acts being corroborated by archaeology.[33]

Acts is divided into two distinct parts. The first (chs. 1–12) deals with the church in Jerusalem and Judaea, and with Peter as central figure—at any rate in the first five chapters. "Yet in cc. vi.-xii.," as Harnack observes,

the author pursues several lines at once. (1) He has still in view the history of the Jerusalem community and the original apostles (especially of Peter and his missionary labors); (2) he inserts in vi. 1 ff. a history of the Hellenistic Christians in Jerusalem and of the Seven Men, which from the first tends towards the Gentile Mission and the founding of the Antiochene community; (3) he pursues the activity of Philip in Samaria and on the coast...; (4) lastly, he relates the history of Paul up to his entrance on the service of the young Antiochene church. In the small space of seven chapters he pursues all these lines and tries also to connect them together, at the same time preparing and sketching the great transition of the Gospel from Judaism to the Greek world. As historian, he has here set himself the greatest task.

No doubt gaps abound in these seven chapters. "But the inquiry as to whether what is narrated does not even in these parts still contain the main facts, and is not substantially trustworthy, is not yet concluded." The difficulty is that there are few external means of testing this portion of the narrative. The second part pursues the history of the apostle Paul, and here the statements made in the Acts may be compared with the Epistles. The result is a general harmony, without any trace of direct use of these letters; and there are many minute coincidences. But attention has been drawn to two remarkable exceptions: the account given by Paul of his visits to Jerusalem in Galatians as compared with Acts; and the character and mission of the apostle Paul, as they appear in his letters and in Acts.

In regard to the first point, the differences as to Paul's movements until he returns to his native province of Syria-Cilicia do not really amount to more than can be explained by the different interests of Paul and the author, respectively. But it is otherwise as regards the visits of Galatians 2:1–10 and Acts 15. If they are meant to refer to the same occasion, as is usually assumed, it is hard to see why Paul should omit reference to the public occasion of the visit, as also to the public vindication of his policy. But in fact the issues of the two visits, as given in Galatians 2:9f. and Acts 15:20f., are not at all the same. Nay more, if Galatians 2:1–10 = Acts 15, the historicity of the "Relief visit" of Acts 11:30, 12:25 seems definitely excluded by Paul's narrative of events before the visit of Galatians 2:1ff. Accordingly, Sir W. M. Ramsay and others argue that the latter visit itself coincided with the Relief visit, and even see in Galatians 2:10 witness thereto.

But why does not Paul refer to the public charitable object of his visit? It seems easier to assume that the visit of Galatians 2:1ff. is altogether unrecorded in Acts, owing to its private nature as preparing the way for public developments—with which Acts is mainly concerned. In that case, it would fall shortly before the Relief visit, to which there may be tacit explanatory allusion, in Galatians 2:10; and it will be shown below that such a conference of leaders in Galatians 2:1ff. leads up excellently both to the First Mission Journey and to Acts 15.

As for Paul as depicted in Acts, Paul claims that he was appointed the apostle to the Gentiles, as Peter was to the Circumcision; and that circumcision and the observance of the Mosaic Law were of no importance to the Christian as such. His words on these points in all his letters are strong and decided, but see also Antinomianism and New Perspective on Paul. But in Acts, it is Peter who first opens up the way for the Gentiles. It is Peter who uses the strongest language in regard to the intolerable burden of the Law as a means of salvation (15:10f.; cf. 1), so-called Legalism (theology). Not a word is said of any difference of opinion between Peter and Paul at Antioch (Gal 2:11ff.). The brethren in Antioch send Paul and Barnabas up to Jerusalem to ask the opinion of the apostles and elders: they state their case, and carry back the decision to Antioch. Throughout the whole of Acts, Paul never stands forth as the unbending champion of the Gentiles. He seems continually anxious to reconcile the Jewish Christians to himself by personally observing the law of Moses. He personally circumcises the semi-Jew, Timothy; and he performs his vows in the temple. He is particularly careful in his speeches to show how deep is his respect for the law of Moses. In all this, the letters of Paul are very different from Acts. In Galatians, he claims perfect freedom in principle, for himself as for the Gentiles, from the obligatory observance of the law; and neither in it nor in Corinthians does he take any notice of a decision to which the apostles had come in their meeting at Jerusalem. The narrative of Acts, too, itself implies something other than what it sets in relief; for why should the Jews hate Paul so much, if he was not in some sense disloyal to their Law?

This is not necessarily a contradiction; only such a difference of emphasis as belongs to the standpoints and aims of the two writers amid their respective historical conditions. Peter's function toward the Gentiles belongs to early conditions present in Judaea, before Paul's distinctive mission had taken shape. Once Paul's apostolate—a personal one, parallel with the more collective apostolate of "the Twelve"—has proved itself by tokens of Divine approval, Peter and his colleagues frankly recognize the distinction of the two missions, and are anxious only to arrange that the two shall not fall apart by religiously and morally incompatible usages (Acts 15). Paul, on his side, clearly implies that Peter felt with him that the Law could not justify (Gal 2:15ff.), and argues that it could not now be made obligatory in principle (cf. "a yoke," Acts 15:10); yet for Jews it might continue for the time (pending the Parousia) to be seemly and expedient, especially for the sake of non-believing Judaism. To this he conformed his own conduct as a Jew, so far as his Gentile apostolate was not involved (1 Cor 9:19ff.). There is no reason to doubt that Peter largely agreed with him, since he acted in this spirit in Galatians 2:11f., until coerced by Jerusalem sentiment to draw back for expediency's sake. This incident simply did not fall within the scope of Acts to narrate, since it had no abiding effect on the Church's extension. As to Paul's submission of the issue in Acts 15 to the Jerusalem conference, Acts does not imply that Paul would have accepted a decision in favor of the Judaizers, though he saw the value of getting a decision for his own policy in the quarter where they were most likely to defer. If the view that he already had an understanding with the "Pillar" Apostles, as recorded in Galatians 2:1–10, be correct, it gives the best of reasons why he was ready to enter the later public Conference of Acts 15. Paul's own "free" attitude to the Law, when on Gentile soil, is just what is implied by the hostile rumors as to his conduct in Acts 21:21, which he would be glad to disprove as at least exaggerated (vv. 24 and 26).

(Questions and evidence of historicity are presented in Colin J. Hemer, "The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History," Eisenbrauns, 1990)

Speeches

The speeches in Acts deserve special notice, because they constitute about 20% of the entire book. Given the nature of the times, lack of recording devices, and space limitations, many ancient historians did not reproduce verbatim reports of speeches. Condensing and using one's own style was often unavoidable. Nevertheless, there were different practices when it came to the level of creativity or adherence individual historians practiced.

On one end of the scale were those who seemingly invented speeches, such as the Sicilian historian Timaeus (356–260 B.C.E.). Others, such as Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Tacitus, fell somewhere in between, reporting actual speeches but likely with significant liberty. The ideal for ancient historians, however, seems to have been to try as much as possible to report the sense of what was actually said, rather than simply placing one's own speech in a figure's mouth.

Perhaps the best example of this ideal was voiced by Polybius, who ridiculed Timaeus for his invention of speeches. Historians, Polybius wrote, were "to instruct and convince for all time serious students by the truth of the facts and the speeches he narrates" (Hist. 2.56.10–12). Another ancient historian, Thucydides, admits to having taken some liberty while narrating speeches, but only when he did not have access to any sources. When he had sources, he used them. In his own words, Thucydides wrote speeches "of course adhering as closely as possible to the general sense of what was actually said" (History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.22.1). Accordingly, as stated by C.W. Fornara, "[t]he principle was established that speeches were to be recorded accurately, though in the words of the historian, and always with the reservation that the historian could 'clarify'" (The Nature of History in Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 145).

On what end of the scale did the author of Acts fall? There is little doubt that the speeches of Acts are summaries or condensations largely in the style and vocabulary of its author. However, there are indications that the author of Acts relied on source material for his speeches, and did not treat them as mere vehicles for expressing his own theology. The author's apparent use of speech material in the Gospel of Luke, obtained from the Gospel of Mark and the hypothetical Q document or the Gospel of Matthew, suggests that he relied on other sources for his narrative and was relatively faithful in using them. Additionally, many scholars have viewed Acts' presentation of Stephen's speech, Peter's speeches in Jerusalem and, most obviously, Paul's speech in Miletus as relying on source material or of expressing views not typical of Acts' author.[3] Additionally, there is no evidence that any speech in Acts is the free composition of its author, without either written or oral basis. Accordingly, in general, the author of Acts seems to be among the conscientious ancient historians, touching the essentials of historical accuracy, even as now understood.

Miracles

Skeptics object to the trustworthiness of Acts[citation needed] on the ground of its reports of miracles, while Christian apologists defend the work as containing earlier sources.

There are possibilities of mistakes intervening between the facts and the accounts reaching its author, at second- or even thirdhand. Some modern scholars argue[citation needed] that Acts shows several errors, and suggest its value as history is doubtful. However, the use of "we" at some points in the book suggests its author was an eyewitness to some of the events he describes.

Quellenkritik, a distinctive feature of recent research upon Acts, solves many difficulties in the way of treating it as an honest narrative by a companion of Paul. In addition, we may also count among recent gains a juster method of judging such a book. For among the results of the Tübingen criticism was what Dr. W. Sanday calls "an unreal and artificial standard, the standard of the 19th century rather than the 1st, of Germany rather than Palestine, of the lamp and the study rather than of active life." This has a bearing, for instance, on the differences between the three accounts of Paul's conversion in Acts. In the recovery of a more real standard, we owe much to men like Mommsen, Ramsay, Blass and Harnack, trained amid other methods and traditions than those which had brought the constructive study of Acts almost to a deadlock.

Structure

The structure of the book of Luke[34] is closely tied with the structure of Acts.[35] Both books are most easily tied to the geography of the book. Luke begins with a global perspective, dating the birth of Jesus to the reign of the Roman emperors in Luke 2:1 and 3:1. From there we see Jesus' ministry move from Galilee (chapters 4–9), through Samaria and Judea (chs. 10–19), to Jerusalem where he is crucified, raised and ascended into heaven (chs. 19–24). The book of Acts follows just the opposite motion, taking the scene from Jerusalem (chs. 1–5), to Judea and Samaria (chs. 6–9), then traveling through Syria, Asia Minor, and Europe towards Rome (chs. 9–28). This chiastic structure emphasizes the centrality of the resurrection and ascension to Luke's message, while emphasizing the universal nature of the gospel.

This geographic structure is foreshadowed in Acts 1:8, where Jesus says "You shall be My witnesses both in Jerusalem (chs. 1–5), and in all Judea and Samaria (chs. 6–9), and even to the remotest part of the earth (chs. 10–28)." The first two sections (chs. 1–9) represent the witness of the apostles to the Jews, while the last section (chs. 10–28) represent the witness of the apostles to the Gentiles.

The book of Acts can also be broken down by the major characters of the book. While the complete title of the book is the Acts of the Apostles, really the book focuses on only two of the apostles: Peter (chs. 1–12) and Paul (chs. 13–28).

Within this structure, the sub-points of the book are marked by a series of summary statements, or what one commentary calls a "progress report." Just before the geography of the scene shifts to a new location, Luke summarizes how the gospel has impacted that location. The standard for these progress reports is in 2:46–47, where Luke describes the impact of the gospel on the new church in Jerusalem. The remaining progress reports are located:

- Acts 6:7 Impact of the gospel in Jerusalem.

- 9:31 Impact of the gospel in Judea and Samaria.

- 12:24 Impact of the gospel in Syria.

- 16:5 Impact of the gospel in Asia Minor.

- 19:20 Impact of the gospel in Europe.

- 28:31 Impact of the gospel on Rome.

This structure can be also seen as a series of concentric circles, where the gospel begins in the center, Jerusalem, and is expanding ever outward to Judea & Samaria, Syria, Asia Minor, Europe, and eventually to Rome.

Date

External evidence now points to the existence of Acts at least as early as the opening years of the 2nd century. Conservative Christian scholars date the book of Acts early. For example, Norman Geisler dates the book of Acts being written between 60-62 C.E. for a number of reasons.[36] As evidence for the Third Gospel holds equally for Acts, its existence in Marcion's day (120–140) is now assured.[citation needed] Further, the traces of it in Polycarp 6 and Ignatius 7 when taken together are highly probable; and it is even widely admitted that the resemblance of Acts 13:22 and First Clement 18:1, in features not found in Psalms 89:20 quoted by each, can hardly be accidental. That is, Acts was probably current in Antioch and Smyrna not later than circa 115, and perhaps in Rome as early as circa 96.

With this view internal evidence agrees. In spite of some advocacy of a date prior to 70 since the book of Acts does not mention the destruction of Jerusalem, the bulk of critical opinion is decidedly against it[citation needed]. The prologue to Luke's Gospel itself implies the dying out of the generation of eyewitnesses as a class. A strong consensus supports a date about 80; some prefer 75 to 80; while a date between 70 and 75 seems no less possible. Two points used by advocates of pre-70 authorship is the fact that (1) Nero's mass execution of Christians in 64 is omitted, and (2) Paul's death is not recorded. Although point two can be addressed as being off focus with respect to Acts, the numerous amount of Christians that were killed would surely have contained a motif for the writer to record since in the very least it would offer a case of martyrdom. Of the reasons for a date in one of the earlier decades of the 2nd century, as argued by the Tübingen school and its heirs, several are now untenable. Among these are the supposed traces of 2nd-century Gnosticism and "hierarchical" ideas of organization[citation needed]; but especially the argument from the relation of the Roman state to the Christians, which Ramsay[citation needed] has reversed and turned into proof of an origin prior to Pliny's correspondence with Trajan on the subject. Another fact, now generally admitted[citation needed], renders a 2nd-century date yet more incredible; and that is the failure of a writer devoted to Paul's memory to make palpable use of his Epistles. Instead of this he writes in a fashion that seems to traverse certain things recorded in them. If, indeed, it were proved that Acts uses the later works of Josephus, we should have to place the book about 100. But this is far from being the case.

Three points of contact with Josephus in particular are cited. (1) The circumstances attending the death of Agrippa I in 44. Here Acts 12:21–23 is largely parallel to his Antiquities 19.8.2; but the latter adds an omen of coming doom, while Acts alone gives a circumstantial account of the occasion of Herod's public appearance. Hence the parallel, when analyzed, tells against dependence on Josephus. So also with (2) the cause of the Egyptian pseudo-prophet in Acts 21:37f. and in Josephus (J.W. 2.13.5; A.J. 20.8.6) for the numbers of his followers do not agree with either of Josephus's rather divergent accounts, while Acts alone calls them Sicarii. With these instances in mind, it is natural to regard (3) the curious resemblance as to the (nonhistorical) order in which Theudas and Judas of Galilee are referred to in both (Acts 5:36f.; A.J. 20.5.1) as accidental.

It is worth noting, however, that no ancient source actually mentions Acts by name prior to 177. If it were composed prior to then, no one spoke of it by that name, or at least no one whose writings have survived down to the present day. This being an argument from silence, not withstanding, that just as previously mentioned Saint Ignatius of Antioch (c. 35-107) quotes from the book of Acts as he also quotes from the gospel of Luke. St Polycarp of Smyrna (birth unknown, death ca. 155) as well quotes from the book of Acts

Place

The place of composition is still an open question. For some time Rome and Antioch have been in favor, and Blass combined both views in his theory of two editions. But internal evidence points strongly to the Roman province of Asia, particularly the neighborhood of Ephesus. Note the confident local allusion in 19:9 to "the school of Tyrannus" and in 19:33 to "Alexander"; also the very minute topography in 20:13–15. At any rate affairs in that region, including the future of the church of Ephesus (20:28–30), are treated as though they would specially interest "Theophilus" and his circle; also an early tradition makes Luke die in the adjacent Bithynia. Finally it was in this region that there arose certain early glosses (e.g., 19:9; 20:15), probably the earliest of those referred to below. How fully in correspondence with such an environment the work would be, as apologia for the Church against the Synagogue's attempts to influence Roman policy to its harm, must be clear to all familiar with the strength of Judaism in Asia (cf. Rev 2:9, 3:9; and see Sir W. M. Ramsay, The Letters to the Seven Churches, ch. xii.).

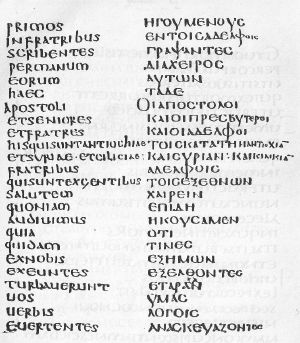

Manuscripts

Like most biblical books, there are differences between the earliest surviving manuscripts of Acts. In the case of Acts, however, the differences between the surviving manuscripts is more substantial. The two earliest versions of manuscripts are the Western text-type (as represented by the Codex Bezae) and the Alexandrian text-type (as represented by the Codex Sinaiticus). The version of Acts preserved in the Western manuscripts contains about 10% more content than the Alexandrian version of Acts. Since the difference is so great, scholars have struggled to determine which of the two versions is closer to the original text composed by the original author.

The earliest explanation, suggested by Swiss theologian Jean LeClerc in the 17th century, posits that the longer Western version was a first draft, while the Alexandrian version represents a more polished revision by the same author. Adherents of this theory argue that even when the two versions diverge, they both have similarities in vocabulary and writing style— suggesting that the two shared a common author. However, it has been argued that if both texts were written by the same individual, they should have exactly identical theologies and they should agree on historical questions. Since most modern scholars do detect subtle theological and historical differences between the texts, most scholars do not subscribe to the rough-draft/polished-draft theory.

A second theory assumes common authorship of the Western and Alexandrian texts, but claims the Alexandrian text is the short first draft, and the Western text is a longer polished draft. A third theory is that the longer Western text came first, but that later, some other redactor abbreviated some of the material, resulting in the shorter Alexandrian text.

While these other theories still have a measure of support, the modern consensus is that the shorter Alexandrian text is closer to the original, and the longer Western text is the result of later insertion of additional material into the text.[37] It is believed that the material in the Western text which isn't in the Alexandrian text reflects later theological developments within Christianity. For examples, the Western text features a greater hostility to Judaism, a more positive attitude towards a Gentile Christianity, and other traits which appear to be later additions to the text. Some also note that the Western text attempts to minimize the emphasis Acts places on the role of women in the early Christian church.[38]

A third class of manuscripts, known as the Byzantine text-type, is often considered to have developed after the Western and Alexandrian types. The extant manuscripts of this type date from the 5th century or later; however, papyrus fragments show that this text-type may date as early as the Alexandrian or Western text-types.[39] The Byzantine text-type served as the basis for the 16th century Textus Receptus, the first Greek-language version of the New Testament to be printed by printing press. The Textus Receptus, in turn, served as the basis for the New Testament found in the English-language King James Bible. Today, the Byzantine text-type is the subject of renewed interest as the possible original form of the text from which the Western and Alexandrian text-types were derived.[40]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Carson, D. A., Moo, Douglas J. and Morris, Leon An Introduction to the New Testament (Leicester: Apollos, 1999), 181.

- ↑ Some believe this refers to his second coming on the clouds, while others hold that say this cannot be, since the disciples are told not to look to the sky for his return.

- ↑ Catholic tradition, which affirms Mary's perpetual virginity, denies these "brothers" are Mary's sons, interpreting them to be either cousins or Joseph's sons by a previous marriage.

- ↑ Hellenistic Jews, here, were apparently those whose origins were in the diaspora and were less connected to the Jerusalem tradition of the early believers in Jesus

- ↑ apparently not the apostle, since they have stayed in Jerusalem

- ↑ In later tradition, Simon is thought to be the first of the Gnostic heretics. The term "simony"—the buying of ecclesiastical office—is derived from his name.

- ↑ The fact that these men are baptized into the faith without first being circumcized is significant in showing that not only Paul, but Peter, too, practiced this tradition.

- ↑ Many scholars believe these chapters are related to the incident in Galatians 3 in which Paul criticizes Peter for refusing to eat with Gentiles, seeing a tendency in Luke to play down the any tension between the Pauline tradition and that of Peter or the Jerusalem church

- ↑ As a Levite, Barnabas would be particularly knowledgable about Jewish tradition. He is thus and interesting choice as Jerusalem's representative to the first Gentile Christian community.

- ↑ Some have suggested that these prophets may be the "men from James" with whom Paul has such difficulty. Galatians 3 also reveals a split between Peter and Paul, with Peter refusing to eat with Gentiles and Paul publicly condemning him for this. In the argument, Barnabas, the Levite, sides with Peter. That such an event could have happened after Peter's supposed revelation from God is highly doubtly, leaving many to question whether the episode of Acts 10-11 is out of chronological order, or perhaps even fictional.

- ↑ However, the account differs significantly from Acts, and some argue Gal 2 is a different meeting.

- ↑ Acts 1:5, 8; 2:1-4; 11:15-16 according to here

- ↑ Acts 15:28; 16:6-7; 19:21; 20:22-23 according to here

- ↑ Acts 1:8; 2:4; 4:8, 31; 11:24; 13:9, 52 according to here

- ↑ e.g. "Preach good news to the poor" (Luke 4:18), "Blessed are the poor" (Luke 6:20–21), Luke's Attitude Towards Rich and Poor

- ↑ Luke 1, Luke 2

- ↑ Luke 2:37; 4:25-26; 7:12; 18:3, 5; 20:47; 21:2-3)

- ↑ e.g. the good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37), the story of the Samaritan who expressed gratitude to Jesus for being healed (Luke 17:11-19),and the entrance of the Samaritans into the church of God (Acts 8:4-25).

- ↑ Theology of prayer in the gospel of Luke

- ↑ Listed here

- ↑ (Udo Schnelle, The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings, p. 259).

- ↑ (Haer. 3.1.1, 3.14.1)

- ↑ (Marc. 4.2.2)

- ↑ (Paed. 2.1.15 and Strom. 5.12.82)

- ↑ Acts 16:10–17, 20:5–15, 21:1–18, and 27:1–28:16

- ↑ Acts 16:10

- ↑ V.K. Robbins [http://christianorigins.com/bylandbysea.html By Land and By Sea: The We-Passages and Ancient Sea Voyages]

- ↑ Carson, D. A., Moo, Douglas J. and Morris, Leon An Introduction to the New Testament (Leicester: Apollos, 1999), 181.

- ↑ Phillips, Thomas E. "The Genre of Acts: Moving Toward a Consensus?" Currents in Biblical Research 4 [2006] 365 - 396.

- ↑ Randel McCram Helms (1997) Who Wrote The Gospels

- ↑ Luke and Josephus

- ↑ A. N. Sherwin-White, Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963), p. 189.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ See, for example, Gooding, David W., According to Luke, (1987) ISBN 0-85110-756-7

- ↑ See, for example, Gooding, David W., True to the Faith, (1990) ISBN 0-340-52563-0

- ↑ [2].

- ↑ The Text of Acts

- ↑ The influence on the Textus Receptus and the KJV of the Western Text's "anti-feminist bias"

- ↑ Such as P66 and P75. See: E. C. Colwell, Hort Redivisus: A Plea and a Program, Studies in Methodology in Textual Criticism of the New Testament, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969, p. 45-48.

- ↑ See: Robinson, Maurice A. and Pierpont, William G., The New Testament in the Original Greek, (2005) ISBN 0-7598-0077-4

External links

- Acts (NRSV) at Oremus Bible Browser

- Dating Acts

- Unbound Bible 100+ languages/versions at Biola University

- Online Bible at gospelhall.org

- Book of Acts at Bible Gateway (NIV & KJV)

- Acts from the Biblical Resource Database

- The Apostle Paul's Shipwreck: An Historical Investigation of Acts 27 and 28

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Acts of the Apostles

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Acts of the Apostles

- Jewish Encyclopedia: New Testament - The Acts of the Apostles

- Tertullian.org: The Western Text of the Acts of the Apostles (1923) J. M. WILSON, D.D.

| Preceded by: John |

Books of the Bible |

Succeeded by: Romans |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.