Difference between revisions of "Shaktism" - New World Encyclopedia

m (relocated a section) |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

[[Image:Mehrgarh figurine3000bce.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The roots of Shaktism? A [[Harappa|Harappan]] goddess figurine, c. 3000 B.C.E. (Musée Guimet, Paris)]] | [[Image:Mehrgarh figurine3000bce.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The roots of Shaktism? A [[Harappa|Harappan]] goddess figurine, c. 3000 B.C.E. (Musée Guimet, Paris)]] | ||

| − | The roots of Shaktism penetrate deep into [[India]]'s prehistory. The earliest Mother Goddess figurine unearthed in India | + | The roots of Shaktism penetrate deep into [[India]]'s prehistory. The earliest Mother Goddess figurine unearthed in India near Allahabad and has been carbon-dated back to the [[Upper Paleolithic]], approximately 20,000 B.C.E. Also dating back to that period are collections of colorful stones marked with natural triangles. Discovered near Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh, they are similar to stones still worshiped as Devi by local tribal groups. Moreover, they may be connected to the later use of ''yantras'' in the Tantric tradition, in which triangles are symbolically linked to fertility.<ref>Joshi, p.</ref> Thousands of female statuettes dated as early as c. 5500 B.C.E. have been recovered at [[Mehrgarh]], one of the most important [[Neolithic]] sites in world archaeology, and a precursor to the great [[Indus Valley Civilization]], suggesting yet another early example of the presence of the Mother Goddess in the Indian context.<ref>Subramuniyaswami, p. 1211.</ref> |

| − | + | The later population centers of the Indus Valley Civilization at Harappa]] and Mohenjo-daro (dated c. 3300 - 1600 BCE) were inhabited by a diverse mix of peoples. The majority came from the adjacent villages to seek the prosperity of the city, and they brought with them their own cults and rituals, including the notion of the feminine divine. These cults of the goddess were promptly given an elevated position in the society, and went on to form the basis of Indus Valley religion. <ref>N.N. Bhattacharyya, ''History of the Sakta Religion'', Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974), </ref> While it is impossible to precisely reconstruct the religious beliefs of a civilization so distantly removed in time, it has been proposed, based on archaeological and anthropological evidence, that this period contains the first seeds of what would become the Shakta religion. | |

| − | + | As these philosophies and rituals developed in the northern reaches of the subcontinent, additional layers of Goddess-focused tradition were expanding outward from the sophisticated Dravidian civilizations of the south. The cult of the goddess was also a major aspect of Dravidian religion, and their female deities eventually came to be identified with the [[Puranic]] goddesses [[Parvati]], [[Durga]] or [[Kali]]. The cult of the ''Sapta Matrikas'', or the "Seven Divine Mothers", which is an integral part of the Shakta religion, may also have been inspired by the Dravidians.<ref>Bhattacharyya(a), p.21</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | As these philosophies and rituals developed in the northern reaches of the subcontinent, additional layers of Goddess-focused tradition were expanding outward from the sophisticated | ||

==Philosophical Development== | ==Philosophical Development== | ||

| − | The | + | ===The Vedas=== |

| − | |||

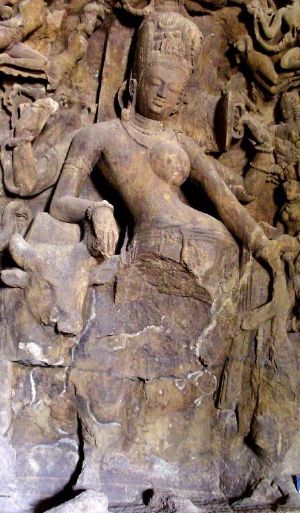

[[Image:Lajja gauri.jpg|thumb|200px|A sandstone sculpture of [[Lajja Gauri]] or [[Aditi]], also called ''uttānapad'' ("she who crouches with legs spread"), c. 650 C.E. (Badami Museum, India).]] | [[Image:Lajja gauri.jpg|thumb|200px|A sandstone sculpture of [[Lajja Gauri]] or [[Aditi]], also called ''uttānapad'' ("she who crouches with legs spread"), c. 650 C.E. (Badami Museum, India).]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | Nonetheless, the Great Goddess of Indus Valley and Dravidian | + | As the Indus Valley Civilization slowly declined and dispersed, its peoples mixed with other groups to eventually gave rise to Vedic Civilization (c. 1500 - 600 B.C.E.), a more patriarchal society in which female divinity continued to have a place in belief and worship, but generally in a subordinate role, with goddesses serving principally as consorts to the great gods. Nonetheless, the Great Goddess of the Indus Valley and Dravidian religions still loomed large in the ''[[Vedas]]'', taking the mysterious form of ''[[Aditi]]'', the "Vedic Mother of the Gods". Aditi is mentioned about 80 times in the ''[[Rigveda]]'', and her appellation (meaning "without limits" in Sanskrit) marks what is perhaps the earliest name used to personify the infinite <ref>Bhattacharyya, </ref> Vedic descriptions of Aditi are vividly reflected in the countless ''[[Lajja Gauri]]'' idols – depicting a faceless, lotus-headed goddess in birthing posture – that have been worshiped throughout India for millennia.<ref>Bolon, Carol Radcliffe, ''Forms of the Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art'', The Pennsylvania State University Press (University Park, Penn., 1992).</ref> An example of such a description reads as follows: |

| − | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | '' | + | ''In the first age of the gods, existence was born from non-existence. The quarters of the sky were born from she who crouched with legs spread. The earth was born from she who crouched with legs spread, and from the earth the quarters of the sky were born.''<ref>Anonymous (author), Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy (translator), ''The Rig Veda: An Anthology of One Hundred Eight Hymns''. Penguin Classics (London, 1982), X.72.3-4</ref> |

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Also in the Vedas, the historically recurrent theme of the Devi's all-encompassing, pan-sexual nature explicitly arises for the first time in such declarations as: ''"Aditi is the sky, Aditi is the air, Aditi is all gods. [...] Aditi is the Mother, the Father, and the Son. Aditi is whatever shall be born."'' <ref>Anonymous (author), Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy (translator), ''The Rig Veda: An Anthology of One Hundred Eight Hymns''. Penguin Classics (London, 1982), ''Rigveda'', I.89.10</ref> | Also in the Vedas, the historically recurrent theme of the Devi's all-encompassing, pan-sexual nature explicitly arises for the first time in such declarations as: ''"Aditi is the sky, Aditi is the air, Aditi is all gods. [...] Aditi is the Mother, the Father, and the Son. Aditi is whatever shall be born."'' <ref>Anonymous (author), Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy (translator), ''The Rig Veda: An Anthology of One Hundred Eight Hymns''. Penguin Classics (London, 1982), ''Rigveda'', I.89.10</ref> | ||

| − | Other goddess forms appearing prominently in the Vedic period include [[Ushas]], who | + | Other goddess forms appearing prominently in the Vedic period include the [[Ushas]], the daughters of [[Surya]] who govern the dawn and are mentioned more than 300 times in no less than 20 hymns. ''[[Prithvi]]'', a variation of the archetypal Indo-European [[Earth Mother]] form, is also referenced. More significant is the appearance of two of Hinduism's most widely known and beloved goddesses: ''[[Vāc]]'', today better known as [[Saraswati]]; and ''Srī'', now better known as [[Lakshmi]] in the famous Rigvedic hymn entitled ''Devi Sukta''. Here these goddesses unambiguously declare their divine supremacy, in words still recited by thousands of Hindus each day: |

| − | |||

| − | More significant is the appearance | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

''"I am the Sovereign Queen; the treasury of all treasures; the chief of all objects of worship; whose all-pervading Self manifests all gods and goddesses; whose birthplace is in the midst of the causal waters; who in breathing forth gives birth to all created worlds, and yet extends beyond them, so vast am I in greatness."''<ref>''Rigveda'', Devi Sukta, Mandala X, Sukta 125. Cited in Bhattacharyya, N. N., ''History of the Sakta Religion'', Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).</ref> | ''"I am the Sovereign Queen; the treasury of all treasures; the chief of all objects of worship; whose all-pervading Self manifests all gods and goddesses; whose birthplace is in the midst of the causal waters; who in breathing forth gives birth to all created worlds, and yet extends beyond them, so vast am I in greatness."''<ref>''Rigveda'', Devi Sukta, Mandala X, Sukta 125. Cited in Bhattacharyya, N. N., ''History of the Sakta Religion'', Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This suggests that the feminine was indeed venerated as the supreme divine in the Vedic age, even in spite of the generally patriarchal nature of the texts. | ||

===The Upanishads=== | ===The Upanishads=== | ||

| − | The great [[Kena Upanishad]], | + | The Upanishads, philosophical commentaries which mark the end of the Vedas, provide little attention to the goddesses. The great [[Kena Upanishad]], however, tells a tale in which the Vedic trinity of [[Agni]], [[Vayu]] and [[Indra]] – boasting and posturing in the flush of a recent victory – suddenly find themselves bereft of divine power in the presence of a mysterious ''[[yaksha]]'', or forest spirit. When Indra tries to approach and identify the ''yaksha'' it vanishes, and in its place the Devi appears in the form of a beautiful ''[[yakshini]]'', luminous and "highly adorned": |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | ''"It was [[Parvati|Uma]], the daughter of Himavat. Indra said to her, 'Who was that yaksha?' She replied, 'It is [[Brahman]]. It is through the victory of Brahman that you have thus become great.' After that he knew that it was Brahman."'' <ref>Olivelle, Patrick (translator), ''The Upanisads,'' Oxford University Press (New York, 1998).</ref> </blockquote | + | ''"It was [[Parvati|Uma]], the daughter of Himavat. Indra said to her, 'Who was that yaksha?' She replied, 'It is [[Brahman]]. It is through the victory of Brahman that you have thus become great.' After that he knew that it was Brahman."'' <ref>Olivelle, Patrick (translator), ''The Upanisads,'' Oxford University Press (New York, 1998).</ref> </blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Of the Upanishads listed in the [[Muktika]] – the final Upanisad of the Hindu canon of 108 texts, cataloging the preceding 107 – only nine are classified as Shakta Upanisads. They are here listed with their associated Vedas; i.e., the [[Rigveda]] (RV), the [[Yajurveda|Black Yajurveda]] (KYV), and the [[Atharvaveda]] (AV): | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

# ''Sītā'' (AV) | # ''Sītā'' (AV) | ||

# ''Annapūrṇa'' (AV) | # ''Annapūrṇa'' (AV) | ||

| Line 72: | Line 52: | ||

# ''Saubhāgya'' (RV) | # ''Saubhāgya'' (RV) | ||

# ''Sarasvatīrahasya'' (KYV) | # ''Sarasvatīrahasya'' (KYV) | ||

| − | # ''Bahvṛca'' (RV) | + | # ''Bahvṛca'' (RV) |

| − | + | ||

| − | The | + | The canonical Shakta Upanishads are much more recent, mostly dating between the 13th and 18th centuries. While their archaic Sanskrit usages create the impression that they belong to the ancient past, none of the verses can be traced to a Vedic source. <ref>Krishna Warrier, Dr. A.J., ''The Sākta Upaniṣad-s'', The Adyar Library and Research Center, Library Series, Vol. 89; Vasanta Press (Chennai, 1967, 3d. ed. 1999).</ref> For the most part, these Upanishads are sectarian tracts reflecting doctrinal and interpretative differences between the two principal sects of [[Shri Vidya|Srividya]] [[upasana]] (a major [[Tantric]] form of Shaktism). As a result, the many extant listings of "authentic" Shakta Upanisads are highly variable in their content, inevitably reflecting the respective sectarian biases of their compilers. For non-Tantrics, the Tantric contents of these texts call into question their identity as actual Upanishad.<ref>Brooks, Douglas Renfrew, ''The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism'', The University of Chicago Press (Chicago, 1990).</ref> |

===The Epic Period=== | ===The Epic Period=== | ||

| Line 225: | Line 205: | ||

"Ideas and practices that collectively characterize [the less controversial elements of] Tantrism pervade classical Hinduism. [...] It would be an error to consider Tantrism apart from its complex interrelations with non-Tantric traditions. Literary history demonstrates that [[Vedas|Vedic]]-oriented [[brahmin|brahmins]] have been involved in Shakta Tantrism from its incipient stages of development, that is, from at least the sixth century. While Shakta Tantrism may have originated in [ancient, indigenous] goddess cults, any attempt to distance Shakta Tantrism from the Sanskritic Hindu traditions [...] will lead us astray."<ref>Brooks, p.</ref> | "Ideas and practices that collectively characterize [the less controversial elements of] Tantrism pervade classical Hinduism. [...] It would be an error to consider Tantrism apart from its complex interrelations with non-Tantric traditions. Literary history demonstrates that [[Vedas|Vedic]]-oriented [[brahmin|brahmins]] have been involved in Shakta Tantrism from its incipient stages of development, that is, from at least the sixth century. While Shakta Tantrism may have originated in [ancient, indigenous] goddess cults, any attempt to distance Shakta Tantrism from the Sanskritic Hindu traditions [...] will lead us astray."<ref>Brooks, p.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | |||

==Worship in Shaktism== | ==Worship in Shaktism== | ||

Revision as of 23:33, 19 October 2007

Shaktism is a denomination of Hinduism that worships Shakti (or [[Devi]) — the female principle of the divine — in her many forms as the absolute, ultimate godhead. Practitioners of Shaktism (commonly known as Shaktas) conceive the goddess as the personification of the universe's primordial energy and, therefore she is the source of the cosmos. [1] Shaktism is, along with Shaivism and Vaishnavism, one of the three primary monotheistic devotional schools of contemporary Hinduism. In the details of its philosophy and practice, Shaktism greatly resembles Saivism, as the god Shiva is considered the consort of the Divine Mother.

Early Origins

The roots of Shaktism penetrate deep into India's prehistory. The earliest Mother Goddess figurine unearthed in India near Allahabad and has been carbon-dated back to the Upper Paleolithic, approximately 20,000 B.C.E. Also dating back to that period are collections of colorful stones marked with natural triangles. Discovered near Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh, they are similar to stones still worshiped as Devi by local tribal groups. Moreover, they may be connected to the later use of yantras in the Tantric tradition, in which triangles are symbolically linked to fertility.[2] Thousands of female statuettes dated as early as c. 5500 B.C.E. have been recovered at Mehrgarh, one of the most important Neolithic sites in world archaeology, and a precursor to the great Indus Valley Civilization, suggesting yet another early example of the presence of the Mother Goddess in the Indian context.[3]

The later population centers of the Indus Valley Civilization at Harappa]] and Mohenjo-daro (dated c. 3300 - 1600 B.C.E.) were inhabited by a diverse mix of peoples. The majority came from the adjacent villages to seek the prosperity of the city, and they brought with them their own cults and rituals, including the notion of the feminine divine. These cults of the goddess were promptly given an elevated position in the society, and went on to form the basis of Indus Valley religion. [4] While it is impossible to precisely reconstruct the religious beliefs of a civilization so distantly removed in time, it has been proposed, based on archaeological and anthropological evidence, that this period contains the first seeds of what would become the Shakta religion.

As these philosophies and rituals developed in the northern reaches of the subcontinent, additional layers of Goddess-focused tradition were expanding outward from the sophisticated Dravidian civilizations of the south. The cult of the goddess was also a major aspect of Dravidian religion, and their female deities eventually came to be identified with the Puranic goddesses Parvati, Durga or Kali. The cult of the Sapta Matrikas, or the "Seven Divine Mothers", which is an integral part of the Shakta religion, may also have been inspired by the Dravidians.[5]

Philosophical Development

The Vedas

As the Indus Valley Civilization slowly declined and dispersed, its peoples mixed with other groups to eventually gave rise to Vedic Civilization (c. 1500 - 600 B.C.E.), a more patriarchal society in which female divinity continued to have a place in belief and worship, but generally in a subordinate role, with goddesses serving principally as consorts to the great gods. Nonetheless, the Great Goddess of the Indus Valley and Dravidian religions still loomed large in the Vedas, taking the mysterious form of Aditi, the "Vedic Mother of the Gods". Aditi is mentioned about 80 times in the Rigveda, and her appellation (meaning "without limits" in Sanskrit) marks what is perhaps the earliest name used to personify the infinite [6] Vedic descriptions of Aditi are vividly reflected in the countless Lajja Gauri idols – depicting a faceless, lotus-headed goddess in birthing posture – that have been worshiped throughout India for millennia.[7] An example of such a description reads as follows:

In the first age of the gods, existence was born from non-existence. The quarters of the sky were born from she who crouched with legs spread. The earth was born from she who crouched with legs spread, and from the earth the quarters of the sky were born.[8]

Also in the Vedas, the historically recurrent theme of the Devi's all-encompassing, pan-sexual nature explicitly arises for the first time in such declarations as: "Aditi is the sky, Aditi is the air, Aditi is all gods. [...] Aditi is the Mother, the Father, and the Son. Aditi is whatever shall be born." [9]

Other goddess forms appearing prominently in the Vedic period include the Ushas, the daughters of Surya who govern the dawn and are mentioned more than 300 times in no less than 20 hymns. Prithvi, a variation of the archetypal Indo-European Earth Mother form, is also referenced. More significant is the appearance of two of Hinduism's most widely known and beloved goddesses: Vāc, today better known as Saraswati; and Srī, now better known as Lakshmi in the famous Rigvedic hymn entitled Devi Sukta. Here these goddesses unambiguously declare their divine supremacy, in words still recited by thousands of Hindus each day:

"I am the Sovereign Queen; the treasury of all treasures; the chief of all objects of worship; whose all-pervading Self manifests all gods and goddesses; whose birthplace is in the midst of the causal waters; who in breathing forth gives birth to all created worlds, and yet extends beyond them, so vast am I in greatness."[10]

This suggests that the feminine was indeed venerated as the supreme divine in the Vedic age, even in spite of the generally patriarchal nature of the texts.

The Upanishads

The Upanishads, philosophical commentaries which mark the end of the Vedas, provide little attention to the goddesses. The great Kena Upanishad, however, tells a tale in which the Vedic trinity of Agni, Vayu and Indra – boasting and posturing in the flush of a recent victory – suddenly find themselves bereft of divine power in the presence of a mysterious yaksha, or forest spirit. When Indra tries to approach and identify the yaksha it vanishes, and in its place the Devi appears in the form of a beautiful yakshini, luminous and "highly adorned":

"It was Uma, the daughter of Himavat. Indra said to her, 'Who was that yaksha?' She replied, 'It is Brahman. It is through the victory of Brahman that you have thus become great.' After that he knew that it was Brahman." [11]

Of the Upanishads listed in the Muktika – the final Upanisad of the Hindu canon of 108 texts, cataloging the preceding 107 – only nine are classified as Shakta Upanisads. They are here listed with their associated Vedas; i.e., the Rigveda (RV), the Black Yajurveda (KYV), and the Atharvaveda (AV):

- Sītā (AV)

- Annapūrṇa (AV)

- Devī (AV)

- Tripurātapani (AV)

- Tripura (RV)

- Bhāvana (AV)

- Saubhāgya (RV)

- Sarasvatīrahasya (KYV)

- Bahvṛca (RV)

The canonical Shakta Upanishads are much more recent, mostly dating between the 13th and 18th centuries. While their archaic Sanskrit usages create the impression that they belong to the ancient past, none of the verses can be traced to a Vedic source. [12] For the most part, these Upanishads are sectarian tracts reflecting doctrinal and interpretative differences between the two principal sects of Srividya upasana (a major Tantric form of Shaktism). As a result, the many extant listings of "authentic" Shakta Upanisads are highly variable in their content, inevitably reflecting the respective sectarian biases of their compilers. For non-Tantrics, the Tantric contents of these texts call into question their identity as actual Upanishad.[13]

The Epic Period

Within the Vedic tradition itself, this was the period of the great Vaishnava epics, Mahabharata (c. 400 B.C.E. - 400 C.E.) and Ramayana (c. 200 B.C.E. - 200 C.E.). While the Ramayana marked the definitive entry into the Hindu pantheon of the hugely popular goddess Sita, "no goddess of a purely Shakta character is mentioned" therein.[14] The Mahabharata, by contrast, is full of references that confirm the ongoing vitality of Shakta worship:

"Goddesses of the later Vedas – Ambika, Durga, Katyayani, Śrī, Bhadrakali, etc., whose cults became very popular in subsequent ages – must have been widely worshiped. [...] In fact, from he later Vedic period down to the age of the Mauryas and Shungas, the cult of the Female Principle had a steady growth. It appears that the original tribal religion of the Maurya kings was that of the Mother Goddess." [15]

Although "orthodox followers of the Vedic religion" did not yet count Shiva and Devi within their pantheon, the "tribal basis of the Mother Goddess cult evidently survived in the days of the Mahabharata, as it does survive even today. The Great Epic thus refers to the goddess residing in the Vindhyas, the goddess who is fond of wine and meat (sīdhumāṃsapaśupriyā) and worshiped by the hunting peoples." The ongoing process of Goddess-worshiping tribals "coming into the fold of the caste system [brought with it] a religious reflex of great historical consequence." [16]

However, it is in the Epic's Durga Stotras [17] that "the Devi is first revealed in her true character, [comprising] numerous local goddesses combined into one [...] all-powerful Female Principle." [18]

Meanwhile, the great Tamil epic, Silappatikaram [19] (c. 100 C.E.) was one of several literary masterpieces amply indicating "the currency of the cult of the Female Principle in South India" during this period — and, once again, "the idea that Lakshmi, Saraswati, Parvati, etc., represent different aspects of the same power." [20]

The Puranas

Taken together with the Epics, the vast body of religious and cultural compilations known as the Puranas (most of which were composed during the Gupta period, c. 300 - 600 C.E.) "afford us greater insight into all aspects and phases of Hinduism – its mythology, its worship, its theism and pantheism, its love of God, its philosophy and superstitions, its festivals and ceremonies and ethics – than any other works."[21] Indeed, "the Puranic legends prepared the substratum for what is known as popular Hinduism." [22]

Some of the more important Puranas from the Shakta standpoint are the Markandeya Purana, the Brahmanda Purana, and the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, from which the most central Shakta scriptures are drawn.

Devi Mahatmya

By far, the most important text of Shaktism – sometimes referred to as the "Shakta Bible" – is the Devi Mahatmya, found in the Markandeya Purana. Composed some 1,600 years ago, c. 400-500 C.E., "the text is a compilation and synthesis of far older myths and legends, skillfully integrated into a single narrative." [23] Here, for the first time, "the various mythic, cultic and theological elements relating to diverse female divinities were brought together in what has been called the 'crystallization of the Goddess tradition."[24]

"From the third or fourth century [CE], the long silence that ensued on the suggestive testimony of the Indus Valley is broken by a variety of literary and iconographic evidence, and the religion of the Goddess becomes as much a part of the Hindu written record as the religion of God. The Devi Mahatmya is not the earliest literary fragment attesting to the existence of devotion to a goddess figure, but it is surely the earliest in which the object of worship is conceptualized as Goddess, with a capital G."[25]

The Devi Mahatmya marks the birth of "independent Shaktism"; i.e. the cult of the Female Principle as a distinct philosophical and denominational entity.

"The influence of the cult of the Female Principle placed goddesses by the sides of the gods of all systems as their consorts, and symbols of their energy or shakti. But the entire popular emotion centering round the Female Principle was not exhausted. So need was felt for a new system, entirely female-dominated, as system in which even the great gods like Vishnu or Shiva would remain subordinate to the goddess. This new system – containing vestiges of hoary antiquity, varieties of rural and tribal cults and rituals, and strengthened by newfangled ideas of different ages – came to be known as Shaktism."[26]

The framing narrative of Devi Mahatmya presents a dispossessed king, a merchant betrayed by his family, and a sage whose teachings lead them both beyond existential suffering. The sage instructs by recounting three different epic battles between the Devi and various demonic adversaries (the three tales being governed by, respectively, Mahakali, Mahalakshmi and Mahasaraswati. Most famous is the story of Mahishasura Mardini – Devi as "Slayer of the Buffalo Demon" – one of the most ubiquitous images in Hindu art and sculpture, and a tale known almost universally in India. Among the important goddess forms the Devi Mahatmyam introduced into the Sanskritic mainstream are Kali and the Sapta-Matrika ("Seven Mothers").

"The sage's three tales are allegories of outer and inner experience, symbolized by the fierce battles the all-powerful Devi wages against throngs of demonic foes. Her adversaries represent the all-too-human impulses arising from the pursuit of power, possessions and pleasure, and from illusions of self-importance. Like the battlefield of the Bhagavad Gita, the Devi Mahatmya's killing grounds represent the field of human consciousness [...] The Devi, personified as one supreme Goddess and many goddesses, confronts the demons of ego and dispels our mistaken idea of who we are, for – paradoxically – it is she who creates the misunderstanding in the first place, and she alone who awakens us to our true being."[27]

Lalita Sahasranama

Within Hindu sacred literature, Sahasranamas – literally, "thousand-name" hymns, extolling the various names, deeds and associations of a given deity – constitute a genre in their own right. And within that genre, the Lalita Sahasranama is considered "a veritable classic, widely acknowledged for its lucidity, clarity and poetic excellence."[28]

The Lalita Sahasranama is part of the Brahmanda Purana, but its specific origins and authorship are lost to history. Based upon textual evidence, it is believed to have been composed in South India not earlier than the 9th century CE and not later than the 11th century CE. The text is closely associated with another section of the Brahmanda Purana entitled Lalitopakhyana ("The Great Narrative of Lalita"), which takes the form of a dialogue between Vishnu's avatar Hayagriva and the great sage Agastya, and extols the greatness Devi in the form of Lalita-Tripurasundari, with particular reference to her slaying of the demon Bhandasura.

The text operates on a number of levels, containing not just references to the Devi's physical qualities and exploits but also an encoded guide to philosophy and esoteric practices of the Srividya denominations. In addition, the entire Sahasranama is considered to have high mantric value independent of its content, and certain names or groups of names are prescribed in sadhanas or prayogas to accomplish particular purposes.[29]

"This Sahasranama is not just a masterly exposition of Sri Lalita's cult, but also sets out the deity's diverse epithets – for instance, Kundalini, Nirguna, Saguna, Parashakti [and] Brahman – which continue to evoke reverence as mantras with 'mystic powers.' Also included among the names are other panegyric descriptions that have come to have profound esoteric connotations in Tantric practices, thus epitomizing the fundamental tenets of tantrasastra.[30]

Most Shaktas consider frequent repetition of the Lalita Sahasranama to be "absolutely essential" to their sadhana. It is believed that "each of the thousand names is a mantra in itself, the contemplation of which will reveal the pathway toward [the reciter's] spiritual goal," regardless of whether "the worshiper is a bhakta, a mantric or jnani, a householder or a sanyasi."[31]

Bhakti and Vedanta

The Puranic age also saw the beginnings of the Bhakti movement – a series of "new religious movements of personalistic, theistic devotionalism" that would come to full fruition between 1200 and 1700 C.E., and which still defines the mainstream of Hindu religious practice to this day. The Devi Gita is an important milestone, as the first major Shakta "theistic work [to be] steeped in bhakti, seeing the ultimate reality as a supreme, personal deity, Bhuvaneshvari, and not just as the relatively abstract, philosophical Absolute (the nirguna Brahman)."[32]

Devi Gita

The Devi Gita is the final and most famous portion of the vast scripture known as the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, an 11th-century document dedicated exclusively to the Devi "in her highest iconic mode, as the supreme World-Mother Bhuvaneshvari, beyond birth, beyond marriage, beyond any possible subordination to Shiva." Indeed, "the text's most significant contribution to the Shakta theological tradition is the ideal of a Goddess both single and benign." [33]

The Devi-Bhagavata Purana retells the tales of the Devi Mahatmya in much greater length and detail, embellishing them with Shakta philosophical reflections, while recasting many classic tales from other schools of Hinduism (particularly Vaishnavism) in a distinctly Shakta light:

"The Devi-Bhagavata was intended not only to show the superiority of the Goddess over various male deities, but also to clarify and elaborate on her nature on her own terms [...]. The Goddess in the Devi-Bhagavata becomes less of a warrior goddess, and more a nurturer and comforter of her devotees, and a teacher of wisdom. This development in the character of the Goddess culminates in the Devi Gita." [34]

Unlike the rest of the Purana, the Devi Gita itself narrates no wild and bloody battles; it is entirely preoccupied with the Goddess's beauty, wisdom, power and various means of worship. Bhakti enthusiasts, after all, were becoming "less and less concerned with the god-demon motif per se, and more and more with the emotional, devotional attitude that [lesser divinities] as well as human beings might feel toward one of [the] great gods." [35] In keeping with this evolving view, the Devi Gita "repeatedly stresses the necessity of love for the goddess, with no mention of one's gender, as the primary qualification," a view "inspired by the devotional ideals of Shaktism." [36]

Southern Influence

The decline and fall of the Gupta Empire around 700 C.E. marked "not only the end of Northern supremacy over the South [of India], but also the beginning of Southern supremacy over the North [...] political as well as cultural." From this time onward, "religious movements of the South began to exert tremendous influence on the North," and the Southern contribution to Shaktism's emergence was significant:[37]

"Korravai, the Tamil goddess of war and victory, was easily identified with Durga. [...] Durga was kendali, a Tamil word meaning the Divine Principle, beyond form and name and transcending all manifestations. [She] was also identified with the Bhagavati of Kerala and the eternal virgin enshrined in Kanyakumari. She was invoked in one or another of her nine forms, Navadurga, or as Bhadrakali. The Tamil tradition also associates her with Saraswati or Vāc, Cinta Devi and Kalaimagal, as also with Srī and Lakshmi. Thus in Durga the devotee visualised the triple aspects of power, beneficence and wisdom. [38]

Many of the larger southern temples of this period had shrines dedicated to the Sapta Matrika and Jyestha, and "from the earliest period the South had a rich tradition of the cult of the Village mothers concerned with the facts of daily life."[39]

Samkhya and Vedanta

As noted above, Shaktism has strongly associated with Tantric philosophy and methodology; however, its philosophical association with Samkhya and Vedanta also merits note.

"The Samkhya concept of Prakriti [...] evolved out of the primitive conception of a material Earth Mother and later became the strongest theoretical basis of Shaktism. [In fact,] the origin of the Samkhya system may be traced to a pre-Vedic stream which is likely to be matriarchal in nature, while the other stream – represented by the Vedic tribes – is decidedly patriarchal. [This] hypothesis [...] may be substantiated by the fact that (i) the Samkhya conception of Prakriti as the material cause of the universe is incompatible with the Vedantic conception of Brahman; (ii) that the greatest care is taken in the Brahmasutra to refute the Samkhya; and (iii) that there had always been a conscious attempt to revise the Samkhya in light of Vedanta." [40]

Despite such efforts, however, the Vedanta could not rid itself of Shaktism's expanding influence:

"Even in its Advaita form – in which Brahman is the one without a second, the conception of Maya as a Female Principle gradually evolved. Thus Brahman could become the creator only when he was associated with Maya, which was subsequently called his 'eternal energy' (nitya shakti).[41]

The Tantras

Shaktism is strongly associated with Tantric Hindu philosophies (though some more elite and recent schools draw upon Vedanta and Samkhya, these do not reflect the mainstream of Shakta practice and belief).

"Our evidence suggests that there are not clear notrmative differences between the traditions and texts regarded as 'Vedic' and 'Tantric.' Rather, there exist substantive differences regarding content. Thus, the relationship between Vedic and Tantric traditions depends on the interpreter, who will likely be involved at some point in an emotionally charged dispute."[42]

Sir John Woodroffe went to great pains to clarify and "demystify" the actual nature of Tantra as it applies to Shakta practice:

"Mystical states in all religions are experiences of joy. [...] The creative and world-sustaining Mother, as seen in Shakta worship, is a joyous figure crowned with ruddy flashing gems, clad in red raiment, more effulgent than millions of red rising suns, with one hand granting all blessings, and with the other dispelling all fears. It is true that she seems fearful to the uninitiate[d] in her form as Kali, but the worshipers of this form know her as the Wielder of the Sword of Knowledge which, severing man from ignorance – that is, partial knowledge – gives him perfect experience."[43]

Shakti and Shiva

| Part of the series on Hinduism | |

| |

| History · Deities | |

| Denominations · Mythology | |

| Beliefs & practices | |

|---|---|

| Reincarnation · Moksha | |

| Karma · Puja · Maya | |

| Nirvana · Dharma | |

| Yoga · Ayurveda | |

| Yuga · Vegetarianism | |

| Bhakti · Artha | |

| Scriptures | |

| Upanishads · Vedas | |

| Brahmana · Bhagavad Gita | |

| Ramayana · Mahabharata | |

| Purana · Aranyaka | |

| Related topics | |

| Hinduism by country | |

| Leaders · Mandir · | |

| Caste system · Mantra | |

| Glossary · Hindu festivals | |

| Murti | |

Shaktism's focus on the Divine Feminine does not imply a rejection of the importance of masculine and neuter divinity. They are, however, deemed to be inactive in the absence of Shakti. In Hinduism, Shakti is considered the motivating force behind all action and existence in the phenomenal cosmos. The cosmos itself is Brahman; i.e., the concept of an unchanging, infinite, immanent and transcendent reality that provides the divine ground of all being. Masculine potentiality is actualized by feminine dynamism, embodied in multitudinous goddesses who are ultimately reconciled into one.

As religious historian V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar (1896-1953) expressed it, "Shaktism is dynamic Hinduism. The excellence of Shaktism lies in its affirmation of Shakti as Consciousness and of the identity of Shakti and Brahman. In short, Brahman is static Shakti and Shakti is dynamic Brahman." [44] In religious art, this cosmic dynamic is powerfully expressed in the half-Shakti, half-Shiva deity known as Ardhanari.

Thus the relationship between Shakti and Shiva – the Divine Feminine and the Divine Masculine – is understood somewhat differently in Shaktism than in other forms of Hinduism, and this sometimes causes confusion and inaccuracy among commentators. The Shakta conception of the Devi is that virtually everything in creation, seen or unseen (and including Shiva), is none other than her.

Indeed, in the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, a central Shakta scripture, the Devi declares:

"I am Manifest Divinity, Unmanifest Divinity, and Transcendent Divinity. I am Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, as well as Saraswati, Lakshmi and Parvati. I am the Sun and I am the Stars, and I am also the Moon. I am all animals and birds, and I am the outcaste as well, and the thief. I am the low person of dreadful deeds, and the great person of excellent deeds. I am Female, I am Male, and I am Neuter." [45]

The religious scholar C. MacKenzie Brown explains that Shaktism "clearly insists that, of the two genders, the feminine represents the dominant power in the universe. Yet both genders must be included in the ultimate if it is truly ultimate. The masculine and the feminine are aspects of the divine, transcendent reality, which goes beyond but still encompasses them. Devi, in her supreme form as consciousness thus transcends gender, but her transcendence is not apart from her immanence." [46]

Brown's analysis continues, "Indeed, this affirmation of the oneness of transcendence and immanence constitutes the very essence of the divine mother [and her] ultimate triumph. It is not, finally, that she is infinitely superior to the male gods – though she is that, according to [Shaktism] – but rather that she transcends her own feminine nature as Prakriti without denying it."[47]

Alternative interpretations of Shaktism – primarily those of Shaiva commentators, such as Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami – posit the feminine manifest as ultimately a mere vehicle through which the masculine unmanifest Parasiva (Shiva in his highest aspect) can be reached.[48] In this interpretation, the Divine Mother becomes something of a mediatrix, worshiped only in order to attain union with Shiva, who in Shaivism is the impersonal unmanifest absolute. These Shaiva views thus conclude that Shaktism is effectively little more than a sub-denomination of Saivism. In Shaktism itself, this interpretation remains a minority viewpoint.

Tantra and Shaktism

Another widely misunderstood aspect of Shaktism is its close association in the public mind with Tantra – an ambiguous, loaded concept that suggests everything from orthodox temple worship in the south of India, to black magic and occult practices in North India, to ritualized sex in the West.[49]

It should noted at the outset that not all forms of Shaktism are Tantric in nature (just as not all forms of Tantra are Shaktic in nature); and also that the term "Tantra" is itself extremely fluid:

"Tantra is a highly variable and shifting category, whose meaning may differ depending on the particular historical moment, cultural milieu, and political context. If tantra in the Sanskrit texts simply means a particular treatise that "spreads knowledge and saves," tantra in the popular imagination means something quite different indeed – a frightening, dangerous path that leads to other-worldly power and control over the occult forces on the dark side of reality."[50]

When the term "Tantra" is used in relation to authentic Hindu Shaktism, it most often refers to a class of ritual manuals, and – more broadly – to an esoteric methodology of Goddess-focused spiritual discipline (sadhana) involving mantra, yantra, nyasa, mudra and certain elements of traditional kundalini yoga, all practiced under the guidance of a qualified guru after due initiation (diksha) and oral instruction to supplement various written sources.[51]

More controversial elements, such as the infamous Five Ms or panchamakara, are indeed employed under certain circumstances by some Tantric Shakta sects. However, these elements tend to be both overemphasized and grossly sensationalized by commentators (whether friendly or hostile) who are ill-informed regarding authentic doctrine and practice. Moreover, even within the tradition itself there are wide differences of opinion regarding the proper interpretation of the panchamakara (i.e., literal vs. symbolic meanings; use of "substitute" materials, etc.), and some lineages reject them altogether. [52]

In sum, the complex social and historical interrelations of Tantric and non-Tantric elements in Shaktism (and Hinduism in general) are an extremely fraught and nuanced topic of discussion. However, as a general rule:

"Ideas and practices that collectively characterize [the less controversial elements of] Tantrism pervade classical Hinduism. [...] It would be an error to consider Tantrism apart from its complex interrelations with non-Tantric traditions. Literary history demonstrates that Vedic-oriented brahmins have been involved in Shakta Tantrism from its incipient stages of development, that is, from at least the sixth century. While Shakta Tantrism may have originated in [ancient, indigenous] goddess cults, any attempt to distance Shakta Tantrism from the Sanskritic Hindu traditions [...] will lead us astray."[53]

Worship in Shaktism

Among the manifestations of Devi most favoured for worship by Shaktas are Kali (the goddess of destruction and transformation, as well as the "devourer of time"); Durga (an epithet of the Mahadevi, or "Great Goddess," celebrated in the Devi Mahatmya); and Parvati, who is the "root form" of most overtly benevolent goddess forms, such as Ambika or Lalita-Tripurasundari.

These various forms of Devi are approached through the myriad different schools and sects of Shaktism, which offer endless varieties of practices seeking to access the shakti (divine energy or power) that is both her nature and her form. Doctrinally and geographically, Shaktism's two main forms can be broadly classified as the Srikula, or family of Sri (Lakshmi), strongest in South India; and the Kalikula, or family of Kali, which prevails in Northern and Eastern India.

Worship and ritual

Among the manifestations of Devi most favoured for worship by Shaktas are Kali, Durga, and Parvati. Durga is an epithet of Mahadevi, or "Great Goddess," who is celebrated in the Devi Mahatmya. Kali is the goddess of destruction and transformation, as well as the devourer of time, as her name implies (kala means "time," and also means "black"). Parvati is the gentle wife of Shiva, one of the most popular gods of modern Hinduism, and is strongly associated with Kali and other goddesses.

Shakta worship takes many forms, but is heavily influenced by Tantra. Shakti is worshipped in several ways in the course of a puja (worship ceremony), including offerings of sweets and flowers, chanting mantras, using mudras, and typically offering some sort of sacrifice. She is most powerfully worshipped by chanting her bija mantra, which is different for each goddess.

Animal sacrifice is performed in some places in India, including such major sites as Kalighat in Calcutta, West Bengal, where goats are sacrificed on days of Tuesdays and Saturdays, and Kamakhya in Guwahati, Assam. Black male goats are typically sacrificed, as well as male buffalo during Durga Puja, and this practice is a controversial one. The brahmin performing the sacrifice is not allowed to cause pain to the animal, and must wait for the animal to surrender before cutting off the head with a single stroke.The blood is used to bless icons and worshippers, and the meat cooked and served to the worshippers and poor as prasad. Those who are averse to animal sacrifice will use a pumpkin or melon instead, which has become a popular and acceptable substitute.

Shaktism is also fused with local beliefs in villages throughout India. In Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh, she is known as Amma (mother). Rural Bengalis know her as Tushu. The Brahmanical idea of Shakti has become fused with local beliefs in protective village goddesses who punish evil, cure diseases and bring boons and blessings to the people of the village. Major annual festivals throughout India include Durga Puja (October, national), Divali (November, national), Kali Puja (October/November, national), Minakshi Kalyanam (April/May in Madurai, Tamil Nadu) and Ambubachi Mela (June/July in Kamakhya Temple, Guwahati, Assam), which is the most important festival to Shakta Tantriks.

"The goddess is the Adya Shakti, the original energy out of which all things were created. This form has many aspects, and all of them have to be honored and served in the remaining days of the Durgapuja. The long series of oblations, libations, and flower offerings are devoted to the recognition of and deference to the multiple aspects in the original form of the goddess.

This recognition is central to sakti puja; bhed, division within the one goddess, must be revealed so that the full significance of Durga may be comprehended and everything may be reintegrated into the idea, form, and appearance of the goddess.

These aspects must be adored separately; otherwise the goddess is not satisfied."[54]

Srikula: The Family of Sri

Srividya is "one of the premier instances of Hindu Shakta Tantrism."[55] Specifically, it is the tradition (sampradaya) which deals with the worship of Tripurasundari, "the most important Tantric form of Sri/Lakshmi, who is the most benign, beautiful and youthful, yet motherly manifestation of the Supreme Shakti." [56]

Kalikula: The Family of Kali

Sri Ramakrishna, quoted in The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, trans. by Swami Nikhilananda:

Kali is none other than Brahman. That which is called Brahman is really Kali. She is the Primal Energy. When that Energy remains inactive, I call It Brahman,and when It creates, preserves, or destroys, I call It Shakti or Kali. What you call Brahman I call Kali. Brahman and Kali are not different. The are like fire and its power to burn:if one thinks of fire one must think of its power to burn.If one recognizes Kali one must also recognize Brahman; again, if one recognizes Brahman one must recognize Kali. Brahman and Its Power are identical. It is Brahman whom I address as Sakti or Kali.

Principal Goddess Forms

Hindus in general, and Shaktas in particular, approach the Devi in a myriad of forms, depending on many factors, including family tradition, regional practice, guru lineage, personal resonance and so on. There are thousands of goddess forms, many of them associated with particular temples, geographic entities or even individual villages.

However, there are a few highly popular goddess forms that are widely known and worshiped throughout the Hindu world. These principal benevolent goddesses of popular Hinduism are:[57]

- Durga : The Goddess as Mahadevi, Supreme Divinity.

- Sri-Lakshmi: The Goddess of Material Fulfillment (wealth, health, fortune, love, beauty, fertility, etc.); consort (shakti) of Vishnu

- Parvati: The Goddess of Spiritual Fulfillment, Divine Love; consort (shakti) of Shiva

- Saraswati: The Goddess of Cultural Fulfillment (knowledge, music, arts and sciences, etc.); consort (shakti) of Brahma; identified with Saraswati River

- Gayatri: The Goddess as Mother of Mantras

- Ganga: The Goddess as Divine River (Ganges)

- Sita: The Goddess as Rama's consort

- Radha: The Goddess as Krishna's Consort

The Ten Mahavidyas

Goddess groups, such as the "Nine Durgas" (Navadurga), "Eight Lakshmis" (Ashta-Lakshmi) and "Seven Mothers" (Sapta-Matrika) are very common in Shaktism. No group, however, better reveals the elemental nature of Shaktism better than the Ten Mahavidyas. These goddesses are sometimes said to be the Shakta counterparts to the Vaishnava Dasavatara ("Ten Avatars of Vishnu"). [58]

Through these Mahavidyas, Shaktas believe, "the one Truth is sensed in its ten different facets; the Divine Mother is adored and approached as the ten cosmic personalities." [59] The Ten Mahavidyas are considered to be Tantric in nature, and are usually identified as:[60]

- Kali: The Goddess as Cosmic Destruction, Death or "Devourer of Time" (primary deity of Kalikula systems)

- Tara: The Goddess as Guide and Protector

- Tripurasundari (Shodashi): The Goddess Who is "Beautiful in the Three Worlds" (primary deity of Srikula systems); the "Tantric Parvati"

- Bhuvaneshvari: The Goddess as World Mother, or Whose Body is the Cosmos

- Bhairavi: The Fierce Goddess

- Chhinnamasta: The Self-Decapitated Goddess

- Dhumavati: The Widow Goddess

- Bagalamukhi: The Goddess Who Paralyzes Enemies

- Matangi: The Outcaste Goddess (in Kalikula systems); the Prime Minister of Lalita (in Srikula systems); the "Tantric Saraswati"

- Kamala: The Lotus Goddess; the "Tantric Lakshmi"

Some traditions assign the five "benevolent" Mahavidyas (usually Tripurasundari, Tara, Bhuvaneshvari, Matangi and Kamala) to the Srikula and the five "fearsome" Mahavidyas (usually Kali, Bhairavi, Chhinnamasta, Dhumavati and Bagalamukhi) to the Kalikula .[61] But such divisions are extremely flexible, as it is stressed that "the path pertains to the sadhaka and not to the deity."[62]

Major Festivals

Major annual festivals throughout India include Durga Puja (October, national), Divali (November, national), Kali Puja (October/November, national), Minakshi Kalyanam (April/May in Madurai, Tamil Nadu) and Ambubachi Mela (June/July in Kamakhya Temple, Guwahati, Assam), which is the most important festival to Shakta Tantriks.

Shakti Temples

There are 51 important centres of Shakti worship located in the Indian sub-continent, including India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, Tibet and even Pakistan. These are called Shakti Peethas (places of strength). These places of worship are consecrated to the goddess Shakti, the female principal of Hinduism and the main deity of the Shakta sect. They are sprinkled throughout the Indian subcontinent [63].

According to legend, at some time in the Satya Yuga, Daksha performed a yagna (named Vrihaspati) with a desire of taking revenge on Lord Shiva. Daksha was angry because his daughter Sati had married the 'yogi' God Shiva against his wishes. Daksha invited all the deities to the yagna except for Shiva and Sati. The fact that she was not invited did not deter Sati from attending the yagna. She had expressed her desire to attend to Shiva who had tried his best to dissuade her from going. Shiva eventually allowed her to go escorted by his ganas (followers).

But Sati, being an uninvited guest, was not given any respect. Furthermore, Daksha insulted Shiva. Sati was unable to bear her father's insults toward her husband, so she committed suicide by jumping into the pyre.

Enraged at the insult and the injury, Shiva destroyed Daksha's sacrifice, cut off Daksha's head, and replaced it with that of a goat as he restored him to life. Still crazed with grief, he picked up the remains of Sati's body, and danced the dance of destruction through the Universe. The other gods intervened to stop this dance, and the Vishnu's disk, or Sudarshan Chakram, cut through the corpse of Sati. The various parts of the body fell at several spots all through the Indian subcontinent and formed sites which are known as Shakti Peethas today.

At all Shakti Peethas, the Goddess Shakti is accompanied by Lord Bhairava (a manifestation of Lord Shiva).

According to the manuscript old manuscript Mahapithapurana (circa 1690-1720 C.E.), there are 51 such places. Among them, 23 are located in the Bengal region. 14 of these are located in what is now West Bengal, India, while 7 are in what is now Bangladesh.

Preserving the mortal relics of famous and respected individuals was a common practice in ancient India - seen in the Buddhist stupas which preserve the relics of Gautama Buddha. It is believed by some that these 51 peethas preserve the remains of some ancient female sage from whom the legend of Kali could have emerged and then merged with the Purusha- Prakriti (Shiva Shakti) model of Hindu thought.

The modern cities or towns that correspond to these 51 locations can be a matter of dispute, but there are a few that are totally unambiguous - for example, Kalighat in Kolkata/Calcutta and Kamakhya in Assam. According to the Pithanirnaya Tantra the 51 peethas are scattered all over India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Tibet and Pakistan. The Shivacharita besides listing 51 maha-peethas, speaks about 26 more upa-peethas. The Bengali almanac, Vishuddha Siddhanta Panjika too describes the 51 peethas including the present modified addresses. A few of the several accepted listings are given below.[64]. One of the few in South India, Srisailam in Andhra Pradesh became the site for a 2nd century temple. [65]

In the listings:

- "Shakti" refers to the Goddess woshipped (invaribly, in this case, a manifestation of Dakshayani/Parvati/Durga);

- "Bhairava" refers to her consort, a manifestation of Shiva;

- "Organ or Ornament" refers to the body part or piece of jewellery that fell to earth, at the location on which the respective temple is built.

Additionally, there are many temples devoted to various incarnations of the Shakti goddess in most of the villages in India. The rural people often believe that Shakti is the protector of the village, the punisher of evil people, the curer of diseases, and the one who gives welfare to the village. They celebrate Shakti Jataras with a lot of hue and great interest once a year.

Folk Shaktism

Shakta worship takes many forms, but is heavily influenced by Tantra. Shakti is worshipped in several ways in the course of a puja (worship ceremony), including offerings of sweets and flowers, chanting mantras, using mudras, and typically offering some sort of sacrifice. She is most powerfully worshipped by chanting her bija mantra, which is different for each goddess.

There are many varieties of folk Shaktism gravitating around various forms of the Goddess, such as Kali, Durga and a number of forms of Amman. Shaktism is also fused with local beliefs in villages throughout India. In Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh, she is known as Amma (mother). Rural Bengalis know her as Tushu. The Brahmanical idea of Shakti has become fused with local beliefs in protective village goddesses who punish evil, cure diseases and bring boons and blessings to the people of the village.

"The goddess is the Adya Shakti, the original energy out of which all things were created. This form has many aspects, and all of them have to be honored and served in the remaining days of the Durgapuja. The long series of oblations, libations, and flower offerings are devoted to the recognition of and deference to the multiple aspects in the original form of the goddess.

This recognition is central to sakti puja; bhed, division within the one goddess, must be revealed so that the full significance of Durga may be comprehended and everything may be reintegrated into the idea, form, and appearance of the goddess. These aspects must be adored separately; otherwise the goddess is not satisfied." [66]

Misperceptions of Shaktism

Shaktism has at times – both in the past and even into the present day – been dismissed by some critics as a superstitious, black magic-infested practice that hardly qualifies as a true religion at all. Typical of such criticism is this broadside issued by an Indian scholar in the 1920s:

"The Tantras are the bible of Shaktism, [...] identifying all Force with the female principle in nature and teaching an undue adoration of the wives of Shiva and Vishnu to the neglect of their male counterparts. [...] It is certain that a vast number of the inhabitants of India are guided in their daily life by Tantrik teaching, and are in bondage to the gross superstitions inculcated in these writings. And indeed it can scarcely be doubted that Shaktism is Hinduism arrived at its worst and most corrupt stage of development."[67]

Even in the 21st century, it is not uncommon to come across assertions that the Shaiva and Vaishnava schools of Hinduism lead to moksha, or spiritual liberation, whereas Shaktism leads merely to siddhis (occult powers) and bhukti (material enjoyments) – or, at best (according to some Shaiva interpreters), to Shaivism. Such claims are dismissed by serious theologians within Shaktism:

"Each of the [Divine Mother's] vidyas [aspects of wisdom, i.e. goddess forms] is a Brahma Vidya [i.e. a path to Supreme Wisdom]. The sadhaka [spiritual aspirant] of any one of these vidyas attains untimately, if his aspiration is such, the supreme purpose of life – self-realisation and God-realisation, [for] realising the Goddess is not different from [realising] one's self. All of these vidyas are benevolent deities of the highest order, and [thus] do the utmost good to the seeker of the vidya."[68]

Other prejudices are based principally on ignorance and misunderstanding, often related to some of folk-shamanic and left-handed Tantric practices that have traditionally been associated with Shakta systems. and occasionally lead to sensational or outrageous headlines.

For example, animal sacrifice is performed in some places in India, including such major sites as Kalighat in Calcutta, West Bengal, where goats are sacrificed on days of Tuesdays and Saturdays, and Kamakhya in Guwahati, Assam. Black male goats are typically sacrificed, as well as male buffalo during Durga Puja, and this practice is a controversial one. The brahmin performing the sacrifice is not allowed to cause pain to the animal, and must wait for the animal to surrender before cutting off the head with a single stroke. The blood is used to bless icons and worshipers, and the meat cooked and served to the worshipers and poor as prasad. Those who are averse to animal sacrifice, however, will use a pumpkin or melon instead, which has become an increasingly popular and acceptable substitute.

Shaktism in the West

The practice of Shaktism is no longer confined to India. Traditional Shakta temples have sprung up across Southeast Asia, the Americas, Europe, Australia and elsewhere – most of them enthusiastically attended by non-Indian as well as Indian diaspora Hindus. Examples in the United States include the Kali Mandir in Laguna Beach, California, "a traditional temple modeled after the Indian public temple ideal"[69]; and Sri Rajarajeshwari Peetam[70], a Srividya Shakta temple in rural Rush, New York, which was recently the subject an in-depth academic monograph exploring the "dynamics of diaspora Hinduism," including the serious entry and involvement of non-Indians in traditional Hindu religious practice.[71]

Shaktism has also become a focus of some Western spiritual seekers attempting to construct new Goddess-centered faiths. Such groups include Shakti Wicca, which defines itself as "a tradition of eclectic Wicca that draws most of its spiritual inspiration from the Hindu tradition,"[72] and Sha'can, self-described as "a tradition based on the tenets of the Craft (commonly referred to as Wicca) and the Shakta path (Goddess-worshipping path of Hindu Tantra)."[73]

An academic study of Kali enthusiasts in the West noted that these sorts of spiritual hybrids are to be expected. "As shown in the histories of all cross-cultural religious transplants, Kali devotionalism in the West must take on its own indigenous forms if it is to adapt to its new environment." [74] However, such East-West fusions can also raise complex and troubling issues of cultural expropriation:

"A variety of writers and thinkers [...] have found Kali an exciting figure for reflection and exploration, notably feminists and participants in New Age spirituality who are attracted to goddess worship. [For them], Kali is a symbol of wholeness and healing, associated especially with repressed female power and sexuality. [However, such interpretations often exhibit] confusion and misrepresentation, stemming from a lack of knowledge of Hindu history among these authors, [who only rarely] draw upon materials written by scholars of the Hindu religious tradition. The majority instead rely chiefly on other popular feminist sources, almost none of which base their interpretations on a close reading of Kali's Indian background. [...] The most important issue arising from this discussion – even more important than the question of 'correct' interpretation – concerns the adoption of other people's religious symbols. [...] It is hard to import the worship of a goddess from another culture: religious associations and connotations have to be learned, imagined or intuited when the deep symbolic meanings embedded in the native culture are not available."[75]

Another powerful motivation behind Western interest in Shaktism has been suggested by Linda Johnsen, a popular writer on Eastern spirituality, who asserts that many central concepts of Shaktism – including aspects of kundalini yoga, as well as goddess worship – were once "common to the Hindu, Chaldean, Greek and Roman civilizations," but were largely lost to the West, as well as the Near and Middle East, with the rise of the Abrahamic religions:

"Of these four great ancient civilizations, working knowledge of the inner forces of enlightenment has survived on a mass scale only in India. Only in India has the inner tradition of the Goddess endured. This is the reason the teachings of India are so precious. They offer us a glimpse of what our own ancient wisdom must have been. The Indians have preserved our lost heritage. [...] Today it is up to us to locate and restore the tradition of the living Goddess. We would do well to begin our search in India, where for not one moment in all of human history have the children of the living Goddess forgotten their Divine Mother."[76]

Notes

- ↑ Bhattacharyya(a).

- ↑ Joshi, p.

- ↑ Subramuniyaswami, p. 1211.

- ↑ N.N. Bhattacharyya, History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974),

- ↑ Bhattacharyya(a), p.21

- ↑ Bhattacharyya,

- ↑ Bolon, Carol Radcliffe, Forms of the Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art, The Pennsylvania State University Press (University Park, Penn., 1992).

- ↑ Anonymous (author), Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy (translator), The Rig Veda: An Anthology of One Hundred Eight Hymns. Penguin Classics (London, 1982), X.72.3-4

- ↑ Anonymous (author), Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy (translator), The Rig Veda: An Anthology of One Hundred Eight Hymns. Penguin Classics (London, 1982), Rigveda, I.89.10

- ↑ Rigveda, Devi Sukta, Mandala X, Sukta 125. Cited in Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Olivelle, Patrick (translator), The Upanisads, Oxford University Press (New York, 1998).

- ↑ Krishna Warrier, Dr. A.J., The Sākta Upaniṣad-s, The Adyar Library and Research Center, Library Series, Vol. 89; Vasanta Press (Chennai, 1967, 3d. ed. 1999).

- ↑ Brooks, Douglas Renfrew, The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism, The University of Chicago Press (Chicago, 1990).

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Mahabharata, IV.6 and VI.23.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Silappadikaram, Canto XXII, cited in Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Winternitz, M., History of Indian Literature, 2 vols., Calcutta, 1927, 1933, rep., New Delhi, 1973.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996).

- ↑ Kali, Davadatta, In Praise of the Goddess: The Devimahatmya and Its Meaning. Nicolas-Hays, Inc., Berwick, Maine, 2003).

- ↑ Brown, C. MacKenzie, The Triumph of the Goddess: The Canonical Models and Theological Issues of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, State University of New York Press (Suny Series in Hindu Studies, 1991).

- ↑ Coburn, Thomas B., Encountering the Goddess: A translation of the Devi-Mahatmya and a Study of Its Interpretation. State University of New York Press (Albany, 1991).

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996), p. 108.

- ↑ Coburn, Thomas B., Encountering the Goddess: A translation of the Devi-Mahatmya and a Study of Its Interpretation. State University of New York Press (Albany, 1991).

- ↑ Joshi, L. M., Lalita Sahasranama: A Comprehensive Study of the One Thousand Names of Lalita Maha-tripurasundari. D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd (New Delhi, 1998).

- ↑ Suryanarayana Murthy, Dr. C., Sri Lalita Sahasranama with Introduction and Commentary. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan (Mumbai, 2000. Rep. of 1962 ed.)

- ↑ Joshi, L. M., Lalita Sahasranama: A Comprehensive Study of the One Thousand Names of Lalita Maha-tripurasundari. D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd (New Delhi, 1998).

- ↑ Suryanarayana Murthy, Dr. C., Sri Lalita Sahasranama with Introduction and Commentary. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan (Mumbai, 2000. Rep. of 1962 ed.), p. 44 ff.

- ↑ Brown, C. Mackenzie. The Devi Gita: The Song of the Goddess: A Translation, Annotation and Commentary. State University of New York (Albany, 1998), p. 17.

- ↑ Brown, C. Mackenzie. The Devi Gita: The Song of the Goddess: A Translation, Annotation and Commentary. State University of New York (Albany, 1998), pp. 10, 320.

- ↑ Brown, C. Mackenzie. The Devi Gita: The Song of the Goddess: A Translation, Annotation and Commentary. State University of New York (Albany, 1998), p. 8.

- ↑ Brown, C. Mackenzie. The Devi Gita: The Song of the Goddess: A Translation, Annotation and Commentary. State University of New York (Albany, 1998), p. 6.

- ↑ Brown, C. Mackenzie. The Devi Gita: The Song of the Goddess: A Translation, Annotation and Commentary. State University of New York (Albany, 1998), p. 21.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996), p. 109.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996), p. 111.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996), p. 111.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996), p. 113-114.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996), p. 115.

- ↑ Brooks, Douglas Renfrew, The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism, The University of Chicago Press (Chicago, 1990).

- ↑ Woodroffe, Sir John, Sakti and Sakta: Essays and Addresses, Ganesh & Company (Madras, 9th Ed. 1987, reprint of 1927 edition).

- ↑ Dikshitar, p. .

- ↑ Srimad Devi Bhagavatam, cited in Brown, p. ?

- ↑ Brown, p. ?

- ↑ Brown, p. ?

- ↑ Subramuniyaswami, p. 1211.

- ↑ Interview with Sri Girish Kumar, former director of Tantra Vidhya Peethama, Kerala, India, <http://www.heritageindianews.org/Streaming/Audio/Murthy/Thanthrasastra_1.MP3> "Introduction to Tantra Sastra, Part I", broadcast on the Indian spirituality radio show, Mohan's World.

- ↑ Urban, p.?.

- ↑ Brooks, p.?.

- ↑ Woodroffe, p. ?

- ↑ Brooks, p.

- ↑ Source : "The Play of the Gods: Locality, Ideology, Structure and Time in the Festivals of a Bengali Town", Akos Ostor, University of Chicago Press (1980).

- ↑ Coburn, Thomas B., Encountering the Goddess: A translation of the Devi-Mahatmya and a Study of Its Interpretation. State University of New York Press (Albany, 1991).

- ↑ Brooks, Douglas Renfrew, The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism, The University of Chicago Press (Chicago, 1990).

- ↑ Kinsley, David. Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press (Berkeley, 1988), throughout book.

- ↑ Kinsley, David. Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas. University of California Press (Berkeley, 1997), p. 21.

- ↑ Shankarnarayanan, S., The Ten Great Cosmic Powers: Dasa Mahavidyas. Samata Books (Chennai, 1972; 4th ed. 2002), pp. 4, 5.

- ↑ As characterized in Kinsley, David. Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas. University of California Press (Berkeley, 1997), throughout book.

- ↑ Shankarnarayanan, S., The Ten Great Cosmic Powers: Dasa Mahavidyas. Samata Books (Chennai, 1972; 4th ed. 2002), pp. 141-142.

- ↑ Shankarnarayanan, S., The Ten Great Cosmic Powers: Dasa Mahavidyas. Samata Books (Chennai, 1972; 4th ed. 2002), pp. 142.

- ↑ Article, from Banglapedia.

- ↑ 51 Pithas of Parvati - From Hindunet

- ↑ Shakti Pitha sites in India.

- ↑ Ostor, Akos, The Play of the Gods: Locality, Ideology, Structure and Time in the Festivals of a Bengali Town, University of Chicago Press (1980).

- ↑ Kapoor, Subodh, A Short Introduction to Sakta Philosophy, Indigo Books (New Delhi, 2002, reprint of c. 1925 ed.).

- ↑ Shankarnarayanan, S., The Ten Great Cosmic Powers: Dasa Mahavidyas. Samata Books (Chennai, 1972; 4th ed. 2002), p. 5.

- ↑ <http://www.kalimandir.org>|Kali Mandir

- ↑ <http://www.srividya.org>|Sri Rajarajeshwari Peetham

- ↑ Dempsey, Corinne G., The Goddess Lives in Upstate New York: Breaking Convention and Making Home at a North American Hindu Temple. Oxford University Press (New York, 2006).

- ↑ <http://shaktiwicca.tripod.com>|Shakti Wicca: An Eastern-Oriented, Western Path of Balance

- ↑ <http://www.maabatakali.org>|Sharanya: The Maa Batakali Cultural Mission

- ↑ Fell McDermett, Rachel, "The Western Kali," in Hawley, John Stratton (ed.) and Wulff, Donna Marie (ed.), Devi: Goddesses of India. University of California Press (Berkeley, 1996), p. 305.

- ↑ Fell McDermett, Rachel, "The Western Kali," in Hawley, John Stratton (ed.) and Wulff, Donna Marie (ed.), Devi: Goddesses of India. University of California Press (Berkeley, 1996), pp. 281-305.

- ↑ Johnsen, Linda, The Living Goddess: Reclaiming the Tradition of the Mother of the Universe." Yes International Publishers (St. Paul, Minn., 1999).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- (a)Bhattacharyya, N. N., History of the Sakta Religion, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (New Delhi, 1974, 2d ed. 1996)

- (b)Bhattacharyya, N. N., The Indian Mother Goddess, South Asia Books (New Delhi, 1970, 2d ed. 1977).

- Brooks, Douglas Renfrew, The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism, The University of Chicago Press (Chicago, 1990).

- Brown, C. MacKenzie, The Triumph of the Goddess: The Canonical Models and Theological Issues of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, State University of New York Press (Suny Series in Hindu Studies, 1991)

- Dikshitar, V. R. Ramachandra, The Lalita Cult, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (Delhi, 1942, 2d ed. 1991, 3d ed. 1999)

- Joshi, M. C., "Historical and Iconographical Aspects of Shakta Tantrism," in Harper, Katherine (ed.), The Roots of Tantra, State University of New York Press (Albany, 2002).

- Urban, Hugh B., Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics and Power in the Study of Religion, University of California Press (Berkeley, 2003)

- Woodroffe, Sir John, Sakti and Sakta: Essays and Addresses, Ganesh & Company (Madras, 9th Ed. 1987, reprint of 1927 edition)

- Subramuniyaswami, Satguru Sivaya, Merging with Siva: Hinduism's Contemporary Metaphysics, Himalayan Academy (Hawaii, USA, 1999),

- Phyllis K. Herman, California State University, Northridge (USA), "Siting the Power of the Goddess: Sita Rasoi Shrines in Modern India", International Ramayana Conference Held at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL USA, September 21-23, 2001.

- Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions (ISBN 81-208-0379-5) by David Kinsley

- Grace and Mercy in Her Wild Hair : Selected Poems to the Mother Goddess, Ramprasad Sen (1720-1781). (ISBN 0-934252-94-7)

- The Play of the Gods: Locality, Ideology, Structure and Time in the Festivals of a Bengali Town, Akos Ostor, University of Chicago Press (1980), (ISBN 0-226-63954-1)

- Cosmic Puja, Swami Satyananda Saraswati, Devi Mandir (2001), (ISBN 1-877795-70-4)

- Kinsley, David. Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions (ISBN 81-208-0379-5)

- Pintchman, Tracy. The Rise of the Goddess in the Hindu Tradition (ISBN 0-7914-2112-0)

Further reading

- Ostor, Akos, The Play of the Gods: Locality, Ideology, Structure and Time in the Festivals of a Bengali Town, University of Chicago Press (1980). (ISBN 0-226-63954-1)

- Satyananda Saraswati, Swami, Cosmic Puja, Devi Mandir (2001). (ISBN 1-877795-70-4)

- Sen, Ramprasad, Grace and Mercy in Her Wild Hair : Selected Poems to the Mother Goddess. (ISBN 0-934252-94-7)

External links

- Shakti Sadhana: a Hindu spiritual practice that focuses worship upon the Devi. It is also an NGO based in Kerala.

- Sharanya: The Maa Batakali Cultural Mission, Inc.: An international non-profit organization based in San Francisco and Orissa, which teaches Shakta Tantra through a Western framework.

- Sri Swamiji visits Sri Lanka for Shankari Temple Darshan

- Daksha Yagna - The story of Daksha's sacrifice and the origin of the Shakti Pithas

- Gayatri Shaktipeeth, Vatika: An Introduction

- Indian Mythology: Shakti

- A site containing short biographies of several Shakta devotees from the Indian state of Bengal

- Shakti: Listing of usage in Puranic literature

- Shakti temples of India (Includes articles on Shaktism)

- Hindu Goddess worship

- Hindu Goddesses

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.