Albright, Madeleine

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (98 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | ||

{{epname|Albright, Madeleine}} | {{epname|Albright, Madeleine}} | ||

{{Infobox officeholder | {{Infobox officeholder | ||

| image = Secalbright.jpg | | image = Secalbright.jpg | ||

| caption = Official portrait, ca. 1997 | | caption = Official portrait, ca. 1997 | ||

| − | | order = 64th | + | | order = 64th United States Secretary of State |

| − | |||

| president = [[Bill Clinton]] | | president = [[Bill Clinton]] | ||

| deputy = [[Strobe Talbott]] | | deputy = [[Strobe Talbott]] | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| term_start = January 23, 1997 | | term_start = January 23, 1997 | ||

| term_end = January 20, 2001 | | term_end = January 20, 2001 | ||

| − | | order2 = 20th | + | | order2 = 20th United States Ambassador to the United Nations |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| president2 = Bill Clinton | | president2 = Bill Clinton | ||

| predecessor2 = [[Edward J. Perkins]] | | predecessor2 = [[Edward J. Perkins]] | ||

| Line 34: | Line 32: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright''' | + | '''Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright''' (born '''Marie Jana Korbelová'''; May 15, 1937 – March 23, 2022) was an American diplomat and [[political science|political scientist]] who served as the 64th [[United States secretary of state]] from 1997 to 2001. She was the first woman to hold the post. |

| − | Born in [[Prague]], [[Czechoslovakia]], Albright immigrated to the United States after the [[1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état|1948 communist coup d'état]] when she was eleven years old. | + | Born in [[Prague]], [[Czechoslovakia]], Albright immigrated to the United States after the [[1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état|1948 communist coup d'état]] when she was eleven years old. A member of the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]], she worked as an aide to Senator [[Edmund Muskie]] from 1976 to 1978, before serving as a staff member on the [[United States National Security Council|National Security Council]] under [[Zbigniew Brzezinski]]. She served in that position until 1981, when President [[Jimmy Carter]] left office. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | After leaving the National Security Council, Albright joined the academic faculty of [[Georgetown University]] in 1982 and advised Democratic candidates regarding foreign policy. Following the [[1992 United States presidential election|1992 presidential election]], Albright helped assemble President [[Bill Clinton]]'s National Security Council. She was appointed [[United States ambassador to the United Nations]] from 1993 to 1997, a position she held until elevation as secretary of state. Secretary Albright served in that capacity until President Clinton left office in 2001. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Albright was well regarded by her colleagues for her intelligence and effectiveness as a diplomat, despite making a number of controversial statements, which she later withdrew. As the first female Secretary of State she blazed a trail of accomplishment that has been followed by others, and widely recognized. She was awarded the [[Presidential Medal of Freedom]] by President [[Barack Obama]] in May 2012. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Life == | ||

| + | ===Early life in Europe=== | ||

| + | Albright was born Marie Jana Korbelová<ref>[http://www.cnn.com/2013/05/27/us/madeleine-albright-fast-facts Madeleine Albright Fast Facts] ''CNN'', March 24, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2022.</ref> in 1937 in the [[Smíchov]] district of [[Prague]], [[Czechoslovakia]].<ref>[https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/admin/albright.htm Madeleine K. Albright Secretary of State] ''The Washington Post'', 1998. Retrieved May 3, 2022. </ref> Her parents were [[Josef Korbel]], a [[Czechs|Czech]] diplomat, and Anna Korbel (née Spieglová).<ref name="Tablet">[http://tabletmag.com/podcasts/97886/madeleine-albrights-war-years Madeleine Albright's War Years] ''Tablet'', April 26, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> They also had a son, John,<ref>Geraldine Baum, [https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-02-08-ls-29463-story.html A Diplomatic Core] ''Los Angeles Times'', December 8, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> and another daughter, Katherine, born in October 1942 after they had moved to London.<ref name=DobbsOutofPast>Michael Dobbs, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/admin/stories/albright020997.htm Out of the Past] ''The Washington Post'', February 9, 1997. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | When Marie Jana was born, her father was serving as a press-attaché at the Czechoslovak Embassy in [[Belgrade]]. At that time, Czechoslovakia had been independent for less than 20 years, having gained independence from [[Austria-Hungary]] after [[World War I]]. Her father was a supporter of [[Tomáš Masaryk]] and [[Edvard Beneš]].<ref name=DobbsKorbel>Michael Dobbs, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2000/12/28/josef-korbels-enduring-foreign-policy-legacy/8d31958e-07e6-4aff-a3a5-0426f487c9fe/ Josef Korbel's Enduring Foreign Policy Legacy] ''The Washington Post'', December 28, 2000. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> The signing of the [[Munich Agreement]] in September 1938—and the [[Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945)|German occupation of Czechoslovakia]] by [[Adolf Hitler]]'s troops—forced the family into exile because of their links with Beneš.<ref name=Memoir>Madeleine Albright, ''Madam Secretary: A Memoir'' (Miramax, 2003, ISBN 0786868430).</ref> | ||

| − | + | The family moved to Britain in May 1939. Here her father worked for Beneš's [[Czechoslovak government-in-exile]]. Her family first lived on [[Kensington Park Road]] in [[Notting Hill]], London—where they endured the worst of [[the Blitz]]—but later moved to [[Beaconsfield]], then [[Walton-on-Thames]], on the outskirts of London.<ref>Albright 2003, 9–11.</ref> They kept a large metal table in the house, which was intended to shelter the family from the recurring threat of German air raids.<ref>John Carlin, [https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/profile-she-who-knows-tyranny-madeleine-albright-1143508.html Profile: She who knows tyranny; Madeleine Albright] ''The Independent'', February 8, 1998. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> While in England, Marie Jana was one of the children shown in a documentary film designed to promote sympathy for war [[refugee]]s in London.<ref>Albright 2003, 9.</ref> | |

| − | + | Josef and Anna converted from [[Judaism]] to [[Roman Catholicism]] in 1941 to avoid anti-Jewish persecution.<ref name="Tablet" /> Marie Jana and her siblings were raised in the Catholic faith. In 1997, Albright said her parents never told her or her two siblings about their [[Jewish]] ancestry and heritage.<ref name=dobbs>Michael Dobbs, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/admin/stories/albright020497.htm Albright's Family Tragedy Comes to Light] ''The Washington Post'', February 4, 1997. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref><ref name="ushmm_2007-04-12">[https://www.ushmm.org/antisemitism/podcast/voices-on-antisemitism/madeleine-k-albright Voices on Antisemitism interview with Madeleine K. Albright] ''United States Holocaust Memorial Museum'', April 12, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | When ''The Washington Post'' reported on Albright's Jewish ancestry shortly after she had become Secretary of State in 1997, Albright said that the report was a "major surprise."<ref>Franklin Foer, [https://slate.com/news-and-politics/1997/02/did-she-know.html Did She Know?] ''Slate'', February 16, 1997. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> Albright said that she did not learn until age 59 that both her parents were born and raised in Jewish families.<ref>Jaweed Kaleem, [https://www.huffpost.com/entry/madeleine-albright-prague-winter_n_1460500 Madeleine Albright Discusses Her Jewish Background And Her New Book, 'Prague Winter'] ''HuffPost'', April 27, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2022.</ref> As many as a dozen of her relatives in Czechoslovakia—including three of her grandparents—had been murdered in [[the Holocaust]].<ref name=dobbs /><ref name="ushmm_2007-04-12" /> | |

| − | Albright | ||

| − | + | After the defeat of the [[Nazism|Nazis]] in the [[European theatre of World War II]] and the collapse of [[Nazi Germany]] and the [[Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia]], the Korbel family returned to Prague.<ref name=dobbs /> Korbel was appointed as press attaché at Czechoslovakian Embassy in [[Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia|Yugoslavia]], and the family moved to Belgrade—then part of Yugoslavia—which was governed by the [[League of Communists of Yugoslavia|Communist Party]]. Korbel was concerned his daughter would be exposed to [[Marxism]] in a Yugoslav school, and so she was taught privately by a governess before being sent to the Prealpina Institut pour Jeunes Filles finishing school in [[Chexbres]], on [[Lake Geneva]] in Switzerland.<ref>Albright 2003, 15.</ref> She learned to speak French while in Switzerland and changed her name from Marie Jana to Madeleine.<ref>Albright 2003, 4.</ref> | |

| − | + | The [[Communist Party of Czechoslovakia]] took over the [[Government of Czechoslovakia|government]] in 1948, with support from the [[Soviet Union]]. As an opponent of [[communism]], Korbel was forced to resign from his position. He later obtained a position on a United Nations delegation to [[Kashmir]]. He sent his family to the United States, by way of London, to wait for him when he arrived to deliver his report to the [[United Nations Headquarters|UN Headquarters]], then located in [[Lake Success, New York]].<ref>Albright 2003, 17.</ref> | |

| − | The family | + | === In the United States === |

| + | The Korbel family emigrated from the United Kingdom on the [[SS America (1939)|SS ''America'']], departing [[Southampton]] on November 5, 1948, and arriving at [[Ellis Island]] in [[New York Harbor]] on November 11, 1948.<ref name="Dobbs">Michael Dobbs, ''Madeleine Albright: A twentieth-century odyssey'' (Henry Holt and Co., 1999, ISBN 978-0805056594).</ref> The family initially settled in [[Great Neck]] on the [[North Shore (Long Island)|North Shore]] of [[Long Island]] and Korbel applied for [[political asylum]], arguing that as an opponent of Communism, he was under threat in Prague.<ref>Albright 2003, 18–20.</ref> Korbel stated: | ||

| + | <blockquote>I cannot, of course, return to the Communist Czechoslovakia as I would be arrested for my faithful adherence to the ideals of democracy. I would be most obliged to you if you could kindly convey to his Excellency the Secretary of State that I beg of him to be granted the right to stay in the United States, the same right to be given to my wife and three children.<ref>Gerald Knaus, [https://www.esiweb.org/newsletter/albright-hope-europe-whole-and-free-award-our-deal-aegean Albright on hope – Europe whole and free – An award – Our deal in the Aegean] ''European Stability Initiative (ESI)'', December 31, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2022. </ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | With the help of Philip Moseley, a Russian language professor at [[Columbia University]] in New York City, Korbel obtained a position on the staff of the political science department at the [[University of Denver]] in [[Colorado]].<ref>Albright 2003, 20.</ref> He became dean of the university's school of [[international relations]], and later taught future U.S. Secretary of State [[Condoleezza Rice]]. The school was named the [[Josef Korbel School of International Studies]] in 2008 in his honor.<ref name=DobbsKorbel/> | |

| − | + | Madeleine Korbel spent her teen years in [[Denver]] and in 1955 graduated from the [[Kent Denver School]] in [[Cherry Hills Village, Colorado|Cherry Hills Village]], a suburb of Denver. She founded the school's international relations club and was its first president.<ref>Albright 2003, 24.</ref> She attended [[Wellesley College]], in [[Massachusetts]], on a full scholarship, majoring in [[political science]], and graduated in 1959.<ref name=AlbrightGrad>Albright 2003, 47.</ref> The topic of her senior thesis was [[Zdeněk Fierlinger]], a former [[Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia|Czechoslovakian prime minister]].<ref>Albright 2003, 43.</ref> She became a [[Naturalization|naturalized]] [[United States nationality law|U.S. citizen]] in 1957, and joined the [[College Democrats of America]].<ref>Albright 2003, 34–35.</ref> | |

| − | + | While home in Denver from Wellesley, Korbel worked as an intern for ''[[The Denver Post]]''. There she met [[Joseph Albright (journalist)|Joseph Albright]]. He was the nephew of [[Alicia Patterson]], owner of ''[[Newsday]]'' and wife of philanthropist [[Harry Frank Guggenheim]].<ref>Albright 2003, 36.</ref> Korbel converted to the [[Episcopal Church]] at the time of her marriage.<ref name=dobbs /><ref name="ushmm_2007-04-12" /> The couple were married in Wellesley in 1959, shortly after her graduation.<ref name=AlbrightGrad/> They lived in [[Rolla, Missouri]], while Joseph completed his military service at nearby [[Fort Leonard Wood (military base)|Fort Leonard Wood]]. During this time, Albright worked at ''[[The Rolla Daily News]]''.<ref>Albright 2003, 48.</ref> | |

| − | Korbel' | ||

| − | + | The couple moved to Joseph's hometown of [[Chicago]], Illinois, in January 1960. Joseph worked at the ''[[Chicago Sun-Times]]'' as a journalist, and Albright worked as a picture editor for ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]''.<ref>Albright 2003, 49–50.</ref> The following year, Joseph Albright began work at ''[[Newsday]]'' in [[New York City]], and the couple moved to [[Garden City, New York|Garden City]] on Long Island. That year, she gave birth to twin daughters, [[Alice P. Albright|Alice Patterson Albright]] and Anne Korbel Albright. The twins were born six weeks premature and required a long hospital stay. As a distraction, Albright began Russian language classes at [[Hofstra University]] in the [[Hempstead (village), New York|Village of Hempstead]] nearby.<ref>Albright 2003, 52.</ref> | |

| − | + | In 1962, the family moved to [[Washington, D.C.]], where they lived in [[Georgetown (Washington, D.C.)|Georgetown]]. Albright studied international relations and continued in Russian at the [[Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies]], a division of [[Johns Hopkins University]] in the capital.<ref>Albright 2003, 54.</ref> | |

| − | + | Joseph's aunt Alicia Patterson died in 1963 and the Albrights returned to Long Island with the notion of Joseph taking over the family newspaper business.<ref>Albright 2003, 55.</ref> Albright gave birth to another daughter, Katharine Medill Albright, in 1967. She continued her studies at [[Columbia University]]'s Department of Public Law and Government.<ref>Albright 2003, 56.</ref> She earned a certificate in Russian from the [[Harriman Institute|Russian Institute]] (now Harriman Institute),<ref>[https://harriman.columbia.edu/in-memoriam-madeleine-albright-1937-2022/In Memoriam: Madeleine Albright (1937–2022)] ''The Harriman Institute'' March 24, 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2022.</ref> an [[Master of Arts|M.A.]] and a PhD, writing her master's thesis on the [[People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs|Soviet diplomatic corps]] and her doctoral [[dissertation]] on the role of journalists in the [[Prague Spring]] of 1968. She earned her doctorate in 1975.<ref>Albright 2003, 56, 59, 71.</ref> She also took a graduate course given by [[Zbigniew Brzezinski]], who later became her boss at the [[United States National Security Council|U.S. National Security Council]].<ref>Albright 2003, 57.</ref> | |

| − | + | In the early 1980s, upon her return to Washington after traveling in [[Poland]] to research the [[Solidarity]] movement, her husband announced his intention to divorce her so that he could pursue a relationship with another woman.<ref>Albright 2003, 94.</ref> | |

| − | + | She had a long and distinguished career as a diplomat and political scientist, and served as the 64th United States Secretary of State from 1997 to 2001. | |

| − | + | Albright died from [[cancer]] in Washington, D.C., on March 23, 2022, at the age of 84.<ref> Caroline Kelly, [https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/23/politics/madeleine-albright-obituary/index.html Madeleine Albright, first female US secretary of state, dies] ''CNN'', March 23, 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2022.</ref> | |

== Career == | == Career == | ||

=== Early career === | === Early career === | ||

| − | Albright returned to Washington, D.C., in 1968, | + | Albright returned to Washington, D.C., in 1968, commuting to [[Columbia University]] for her Doctor of Philosophy, and began fund-raising for her daughters' school, which led to several positions on education boards.<ref>Albright 2003, 63–66.</ref> She was eventually invited to organize a fund-raising dinner for the 1972 presidential campaign of U.S. Senator [[Ed Muskie]] of [[Maine]].<ref>Albright 2003, 65.</ref> This association with Muskie led to a position as his chief legislative assistant in 1976.<ref name=scott99> A. O. Scott, [https://slate.com/news-and-politics/1999/04/madeleine-albright.html Madeleine Albright: The Diplomat Who Mistook Her Life for Statecraft] ''Slate'', April 25, 1999. Retrieved May 4, 2022.</ref> However, after the [[1976 United States presidential election|1976 U.S. presidential election]] of [[Jimmy Carter]], Albright's former professor Brzezinski was named [[National Security Advisor (United States)|National Security Advisor]], and recruited Albright from Muskie in 1978 to work in the [[West Wing]] as the National Security Council's congressional liaison.<ref name=scott99 /> |

| + | |||

| + | Following Carter's loss in 1980 to [[Ronald Reagan]], Albright moved on to the [[Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars]] at the [[Smithsonian Institution]] in Washington, D.C., where she was given a grant for a research project. She chose to write on the dissident journalists involved in [[Polish People's Republic|Poland]]'s [[Solidarity]] movement, then in its infancy but gaining international attention.<ref>Albright 2003, 91.</ref> She traveled to Poland for her research, interviewing dissidents in [[Gdańsk]], [[Warsaw]], and [[Kraków]].<ref>Albright 2003, 92.</ref> | ||

| − | Albright joined the academic staff at [[Georgetown University]] in Washington, D.C., in 1982, specializing in Eastern European studies.<ref>Albright | + | Albright joined the academic staff at [[Georgetown University]] in Washington, D.C., in 1982, specializing in Eastern European studies.<ref>Albright 2003, 99.</ref> She also directed the university's program on women in global politics.<ref>Albright 2003, 100.</ref> She served as a major [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]] foreign policy advisor, briefing vice-presidential candidate [[Geraldine Ferraro]] in 1984 and presidential candidate [[Michael Dukakis]] in 1988 (both campaigns ended in defeat).<ref>Albright 2003, 102–104.</ref> In 1992, [[Bill Clinton]] returned the [[White House]] to the Democratic Party, and Albright was employed to handle the transition to a new administration at the National Security Council.<ref>Albright 2003, 127.</ref> In January 1993, Clinton nominated her to be [[United States Ambassador to the United Nations|U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations]], her first diplomatic posting.<ref>Albright 2003, 131.</ref> |

=== U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations === | === U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations === | ||

| − | Albright was appointed [[Ambassador to the United Nations]], a [[Cabinet of the United States|Cabinet]]-level position, shortly after Clinton was inaugurated, presenting her credentials on February 9, 1993. During her tenure at the U.N., she had a rocky relationship with the [[Secretary-General of the United Nations|U.N. secretary-general]], [[Boutros Boutros-Ghali]], whom she criticized as "disengaged" and "neglect[ful]" of [[genocide in Rwanda]].<ref name=ms207>Albright | + | Albright was appointed [[Ambassador to the United Nations]], a [[Cabinet of the United States|Cabinet]]-level position, shortly after Clinton was inaugurated, presenting her credentials on February 9, 1993. During her tenure at the [[U.N.]], she had a rocky relationship with the [[Secretary-General of the United Nations|U.N. secretary-general]], [[Boutros Boutros-Ghali]], whom she criticized as "disengaged" and "neglect[ful]" of [[genocide]] in [[Rwanda]].<ref name=ms207>Albright 2003, 207.</ref> She wrote: "My deepest regret from my years in public service is the failure of the United States and the international community to act sooner to halt these crimes."<ref>Albright 2003, 147.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Also in 1996, after Cuban military pilots shot down two small civilian aircraft flown by the Cuban-American exile group [[Brothers to the Rescue]] over international waters, she announced, "This is not | + | In ''[[Shake Hands with the Devil (book)|Shake Hands with the Devil]]'', [[Roméo Dallaire]] writes that in 1994, in Albright's role as the U.S. [[UN Permanent Representative|Permanent Representative to the U.N.]], she avoided describing the killings in Rwanda as "genocide" until overwhelmed by the evidence.<ref>Roméo Dallaire, ''Shake Hands with the Devil'' (Da Capo Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0786715107).</ref> She was instructed to support a reduction or withdrawal (something which never happened) of the [[United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda|U.N. Assistance Mission for Rwanda]] but was later given more flexibility.<ref>Albright 2003, 150–151.</ref> Albright later remarked in [[PBS]] documentary ''Ghosts of Rwanda'' that "it was a very, very difficult time, and the situation was unclear. You know, in retrospect, it all looks very clear. But when you were [there] at the time, it was unclear about what was happening in Rwanda."<ref>[https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/ghosts/interviews/albright.html Interview Madeleine Albright] ''Ghosts of Rwanda'', PBS Frontline, February 25, 2004. Retrieved May 5, 2022.</ref> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Also in 1996, after Cuban military pilots shot down two small civilian aircraft flown by the Cuban-American exile group [[Brothers to the Rescue]] over international waters, she announced, "This is not ''cojones''. This is cowardice."<ref>Albright 2003, 205.</ref> The line endeared her to President Clinton, who said it was "probably the most effective one-liner in the whole administration's foreign policy."<ref>Michael Dobbs and John M. Goshko, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/govt/admin/stories/albright120696.htm Albright's Personal Odyssey Shaped Foreign Policy Beliefs] ''The Washington Post'', December 6, 1996. Retrieved May 5, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In 1996, Albright entered into a secret pact with [[Richard A. Clarke|Richard Clarke]], [[Michael A. Sheehan|Michael Sheehan]], and [[James Rubin]] to overthrow U.N. secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who was running unopposed for a second term in the | + | In 1996, Albright entered into a secret pact with [[Richard A. Clarke|Richard Clarke]], [[Michael A. Sheehan|Michael Sheehan]], and [[James Rubin]] to overthrow U.N. secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who was running unopposed for a second term in the 1996 selection. After 15 U.S. peacekeepers died in a failed raid in [[Somalia]] in 1993, Boutros-Ghali became a political scapegoat in the United States.<ref>John M. Goshko, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/boutros-boutros-ghali-un-secretary-general-who-clashed-with-us-dies-at-93/2016/02/16/8b727bb8-d4c1-11e5-be55-2cc3c1e4b76b_story.html Boutros Boutros-Ghali, U.N. secretary general who clashed with U.S., dies] ''The Washington Post'', February 16, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2022.</ref> They dubbed the pact "Operation Orient Express" to reflect their hope that other nations would join the United States.<ref name=Clarke>Richard Clarke, ''Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror'' (Free Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0743260459). </ref> Although every other member of the [[United Nations Security Council]] voted for Boutros-Ghali, the United States refused to yield to international pressure to drop its lone veto. After four deadlocked meetings of the Security Council, Boutros-Ghali suspended his candidacy and became the only U.N. secretary-general ever to be denied a second term. The United States then fought a four-round veto duel with France, forcing it to back down and accept [[Kofi Annan]] as the next secretary-general. In his memoirs, Clarke said that "the entire operation had strengthened Albright's hand in the competition to be Secretary of State in the second Clinton administration."<ref name=Clarke/> |

=== Secretary of State === | === Secretary of State === | ||

| − | When Clinton began his second term in January 1997 | + | When [[Bill Clinton|Clinton]] began his second term in January 1997, he required a new Secretary of State, as incumbent [[Warren Christopher]] was retiring. The top level of the Clinton administration was divided into two camps on selecting the new foreign policy. Outgoing Chief of Staff [[Leon Panetta]] favored Albright, but a separate faction argued, "anybody but Albright," with [[Sam Nunn]] as its first choice. Albright orchestrated a campaign on her own behalf that proved successful.<ref>Thomas Blood, ''Madam Secretary: A Biography of Madeleine Albright'' (St. Martin's Griffin, 1997, ISBN 978-0312304690).</ref> When Albright took office as the 64th U.S. Secretary of State on January 23, 1997, she became the first female U.S. Secretary of State and the highest-ranking woman in the history of the U.S. government at the time of her appointment.<ref>[https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/people/albright-madeleine-korbel Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Madeleine Korbel Albright (1937–2022)] ''Office of the Historian'', U.S. Department of State. Retrieved May 10, 2022.</ref> Not being a natural-born citizen of the U.S., she was not eligible as a [[United States presidential line of succession|U.S. presidential successor]].<ref>[https://www.usa.gov/presidents#item-35877 Order of Presidential Succession] ''USA.gov''. Retrieved May 10, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | During her tenure, Albright considerably influenced American foreign policy in [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] and the Middle East. | + | During her tenure, Albright considerably influenced American foreign policy in [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] and the Middle East. According to Albright's memoirs, she once argued with [[Colin Powell]] for the use of military force by asking, "What's the point of you saving this superb military, Colin, if we can't use it?"<ref>Albright 2003, 182.</ref> |

| − | As Secretary of State, she represented the U.S. at the | + | As Secretary of State, she represented the U.S. at the transfer of sovereignty over [[Hong Kong]] on July 1, 1997. She along with the British contingents [[boycott]]ed the swearing-in ceremony of the Chinese-appointed Hong Kong Legislative Council, which replaced the elected one.<ref>[http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/9706/10/hong.kong.us/index.html U.S. to boycott seating of new Hong Kong legislature] ''CNN'', June 10, 1997. Retrieved May 10, 2022.</ref> In October 1997, she voiced her approval for national security exemptions to the [[Kyoto Protocol]], arguing that [[NATO]] operations should not be limited by controls on [[greenhouse gas]] emissions, and hoped that other NATO members would also support the exemptions at the [[United Nations Climate Change conference#1997: COP 3, Kyoto, Japan|Third Conference of the Parties]] in Kyoto, Japan.<ref>Burkely Hermann (ed.), [https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/environmental-diplomacy/2022-01-20/national-security-and-climate-change-behind-us National Security and Climate Change: Behind the U.S. Pursuit of Military Exemptions to the Kyoto Protocol] ''National Security Archive''. Retrieved May 10, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[File:Houghton house Netanyahu Albright Arafat.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Albright with [[Benjamin Netanyahu]] (left) and [[Yasser Arafat]] at the [[Wye River Memorandum]], 1998]] | [[File:Houghton house Netanyahu Albright Arafat.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Albright with [[Benjamin Netanyahu]] (left) and [[Yasser Arafat]] at the [[Wye River Memorandum]], 1998]] | ||

| − | According to several accounts, [[Prudence Bushnell]], [[United States Ambassador to Kenya|U.S. Ambassador to Kenya]], repeatedly asked Washington for additional security at the embassy in [[Nairobi]], including in a letter directly addressed to Albright in April 1998. Bushnell was ignored.<ref> | + | According to several accounts, [[Prudence Bushnell]], [[United States Ambassador to Kenya|U.S. Ambassador to Kenya]], repeatedly asked Washington for additional security at the embassy in [[Nairobi]], including in a letter directly addressed to Albright in April 1998. Bushnell was ignored.<ref>James Risen and Benjamin Weiser, [https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/world/africa/010999africa-bomb.html Before Bombings, Omens and Fears] ''The New York Times'', January 9, 1999. Retrieved May 10, 2022. </ref> In ''Against All Enemies'', Richard Clarke writes about an exchange with Albright several months after the [[1998 United States embassy bombings|U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania were bombed]] in August 1998. "What do you think will happen if you lose another embassy?" Clarke asked. "The Republicans in Congress will go after you." "First of all, I didn't lose these two embassies," Albright shot back. "I inherited them in the shape they were."<ref name=Clarke/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In 1998, at the [[NATO summit]], Albright articulated what became known as the " | + | In 1998, at the [[NATO summit]], Albright articulated what became known as the three "D"s of NATO, "which is no diminution of NATO, no discrimination and no duplication – because I think that we don't need any of those three "D"s to happen."<ref>[https://www.nato.int/docu/speech/1998/s981208x.htm Press Conference by US Secretary of State Albright] ''NATO Speeches'', December 8, 1998. Retrieved May 10, 2022.</ref> |

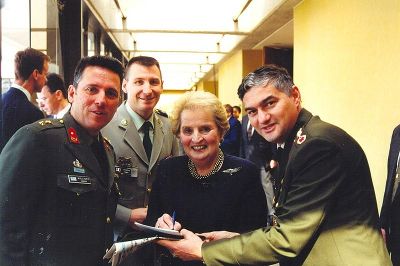

[[File:Madeleine Albright NATO.jpg|thumb|400px|With NATO officers during NATO Ceremony of Accession of New Members, 1999]] | [[File:Madeleine Albright NATO.jpg|thumb|400px|With NATO officers during NATO Ceremony of Accession of New Members, 1999]] | ||

| − | + | Albright became one of the highest level Western diplomats ever to meet [[Kim Jong-il]], the then-leader of communist [[North Korea]], during an official state visit to that country in 2000.<ref>[https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/kim/interviews/albright.html Kim's Nuclear Gamble: Interview Madeleine Albright] ''Frontline'', PBS, March 27, 2003. Retrieved May 10, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Albright became one of the highest level Western diplomats ever to meet [[Kim Jong-il]], the then-leader of communist [[North Korea]], during an official state visit to that country in 2000.<ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Albright | + | On January 8, 2001, in one of her last acts as Secretary of State, Albright made a farewell call to [[Kofi Annan]] and said that the U.S. would continue to press Iraq to destroy all its [[weapons of mass destruction]] as a condition of lifting economic sanctions, even after the end of the Clinton administration on January 20, 2001.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20090605054044/http://www.usembassy.it/file2001_01/alia/a1010801.htm U.S. Will Maintain Pressure on Iraq, Albright Says] January 8, 2001. Retrieved May 10, 2022.</ref> |

=== Post-Clinton administration === | === Post-Clinton administration === | ||

| − | Following Albright's term as Secretary of State, Czech president [[Václav Havel]] spoke openly about the possibility of Albright succeeding him. Albright was reportedly flattered, but denied ever seriously considering the possibility of running for office in her country of origin.<ref> | + | Following Albright's term as Secretary of State, Czech president [[Václav Havel]] spoke openly about the possibility of Albright succeeding him. Albright was reportedly flattered, but denied ever seriously considering the possibility of running for office in her country of origin.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/659215.stm Albright Tipped for Czech Presidency] ''BBC News'', February 28, 2000. Retrieved May 11, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Albright | + | Albright was elected a Fellow of the [[American Academy of Arts and Sciences]] in 2001. Also that year, she founded the [[Albright Group]], an international strategy consulting firm based in Washington, D.C. that later become the [[Albright Stonebridge Group]]. Affiliated with the firm is [[Albright Capital Management]], which was founded in 2005 to engage in private fund management related to emerging markets.<ref> [https://www.albrightcapital.com/what-we-do History] ''Albright Capital''. Retrieved May 11, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Albright accepted a position on the board of directors of the [[New York Stock Exchange]] (NYSE) in 2003.<ref>[https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-may-02-fi-rup2.5-story.html NYSE Nominates Ex-Secretary of State] ''Los Angeles Times'', May 2, 2003. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> In 2005, she declined to run for re-election to the board in the aftermath of the [[Richard Grasso]] compensation scandal, in which Grasso, the chairman of the NYSE Board of Directors, had been granted $187.5 million in compensation, with little governance by the board on which Albright sat.<ref> Andrew Countryman, [https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2005-02-19-0502190101-story.html NYSE includes 3 new names for board] ''Chicago Tribune'', February 19, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> During the tenure of the interim chairman, [[John S. Reed]], Albright served as chairwoman of the NYSE board's nominating and governance committee. Shortly after the appointment of the NYSE board's permanent chairman in 2005, Albright submitted her resignation. | ||

[[File:Secretary Kerry Greets Former Secretary Albright.jpg|thumb|400px|U.S. Secretary of State [[John Kerry]] greets Albright, February 6, 2013]] | [[File:Secretary Kerry Greets Former Secretary Albright.jpg|thumb|400px|U.S. Secretary of State [[John Kerry]] greets Albright, February 6, 2013]] | ||

| + | Albright served on the board of directors for the [[Council on Foreign Relations]] for ten years (2004 to 2014).<ref>[https://www.cfr.org/historical-roster-directors-and-officers Historical Roster of Directors and Officers] ''Council on Foreign Relations''. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> She was the Mortara Distinguished Professor in the Practice of Diplomacy at the [[Georgetown University School of Foreign Service]] in Washington, D.C.<ref>[https://mortara.georgetown.edu/people/faculty/ Faculty] ''Mortara Center for International Studies''. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> Albright served as chairperson of the [[National Democratic Institute for International Affairs]] and as president of the [[Truman Scholarship Foundation]].<ref>[https://www.truman.gov/about-us/officers-board-trustees Officers & Board of Trustees] ''The Harry S. Truman Scholarship Foundation''. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> She was also the co-chair of the [[Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor]].<ref>[https://www1.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/democratic-governance/legal-empowerment/reports-of-the-commission-on-legal-empowerment-of-the-poor/making-the-law-work-for-everyone---vol-ii---english-only/making_the_law_work_II.pdf Making the Law Work for Everyone – Group Report – Volume II] ''United Nations Development Programme'', 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2022. </ref> | ||

| − | Albright | + | At the [[National Press Club (USA)|National Press Club]] in Washington, D.C. on November 13, 2007, Albright declared that she and William Cohen would co-chair a new [[Prevention of Genocide Task Force|Genocide Prevention Task Force]] created by the [[United States Holocaust Memorial Museum]], the [[American Academy of Diplomacy]], and the [[United States Institute for Peace]].<ref>[http://www.economist.com/world/unitedstates/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12773216 Preventing genocide] ''The Economist'', December 18, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> Their appointment was criticized by [[Harut Sassounian]]<ref> |

| − | + | Harut Sassounian, [https://www.huffpost.com/entry/secretaries-albright-and-_b_73628 Secretaries Albright and Cohen Should be Removed from Genocide Task Force] ''Huffington Post'', May. 25, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> and the [[Armenian National Committee of America]], as both Albright and Cohen had spoken against a Congressional resolution on the [[Armenian genocide]].<ref>[https://asbarez.com/armenian-americans-criticize-hypocrisy-of-genocide-prevention-task-force-co-chairs/ Armenian Americans Criticize Hypocrisy of Genocide Prevention Task Force Co-Chairs] ''Asbarez'', December 8, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> | |

[[File:LBJ Foundation DIG14155-46 (37248704094).jpg|thumb|400px|[[Bob Schieffer]] and Madeleine Albright at the [[LBJ Presidential Library]] in 2017]] | [[File:LBJ Foundation DIG14155-46 (37248704094).jpg|thumb|400px|[[Bob Schieffer]] and Madeleine Albright at the [[LBJ Presidential Library]] in 2017]] | ||

| + | Albright endorsed and supported [[Hillary Clinton]] in her 2008 presidential campaign.<ref>Jack Stripling, [https://www.gainesville.com/story/news/2008/03/24/albright-pushing-for-clinton/64292647007/ Albright pushing for Clinton] ''The Gainesville Sun'', March 23, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> After Hillary Clinton was defeated by eventual winner [[Barack Obama]] in the Democratic primaries, Obama nominated then-Senator Clinton for Albright's former post of Secretary of State.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7758673.stm Clinton named Secretary of State] ''BBC News'', December 1, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Albright remained active in various consulting positions until her death. She served as chair of the advisory council for The Hague Institute for Global Justice, which was founded in 2011 in The Hague. She also served as an Honorary Chair for the World Justice Project (WJP), which works to lead a global, multidisciplinary effort to strengthen the rule of law for the development of communities of opportunity and equity. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | A month before her death she wrote an opinion piece in the ''[[New York Times]]'' in which she argued that Russian leader [[Vladimir Putin]] would be making “a historic error” in invading [[Ukraine]] and warned of devastating costs to his country.<ref>Madeleine Albright, [https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/23/opinion/putin-ukraine.html Putin is Making a Historic Mistake] ''The New York Times'', February 23, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Albright | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Controversies == | == Controversies == | ||

=== Sanctions against Iraq === | === Sanctions against Iraq === | ||

| − | On May 12, 1996, then-ambassador Albright defended UN [[sanctions against Iraq]] on a ''[[60 Minutes]]'' segment in which [[Lesley Stahl]] asked her, "We have heard that half a million children have died. I mean, that's more children than died in [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|Hiroshima]]. And, you know, is the price worth it?" and Albright replied, " | + | On May 12, 1996, then-ambassador Albright defended UN [[sanctions against Iraq]] on a ''[[60 Minutes]]'' segment in which [[Lesley Stahl]] asked her, "We have heard that half a million children have died. I mean, that's more children than died in [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|Hiroshima]]. And, you know, is the price worth it?" and Albright replied, "we think the price is worth it."<ref name="MandA">Madeleine Albright, ''The Mighty and the Almighty: Reflections on America, God, and World Affairs'' (Harper, 2006, ISBN 978-0060892579).</ref> The segment won an [[Emmy Award]]. Albright later regretted that she did not challenge the premise of Stahl’s question: that economic sanctions against Iraq were killing hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children.<ref name="Spagat">Michael Spagat, [http://personal.rhul.ac.uk/uhte/014/Truth%20and%20Death.pdf Truth and death in Iraq under sanctions] ''Significance'', September 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2022.</ref> She wrote, "I had fallen into a trap and said something I did not mean,"<ref name=Memoir/> and that she regretted coming "across as cold-blooded and cruel".<ref name="MandA" /> She apologized for her remarks in a 2020 interview with ''[[The New York Times]]'', calling them "totally stupid."<ref>David Marchese, [https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/20/magazine/madeline-albright-interview.html Madeleine Albright Thinks It's Good When America Gets Involved] ''The New York Times'', April 20, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022. </ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Whereas it was widely believed that the sanctions more than doubled Iraq's [[child mortality]] rate, research following the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq has shown that commonly cited data were fabricated by the Iraqi government and that "there was no major rise in child mortality in Iraq after 1990 and during the period of the sanctions" | + | Whereas it was widely believed that the sanctions more than doubled Iraq's [[child mortality]] rate, research following the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq has shown that commonly cited data were fabricated by the Iraqi government and that "there was no major rise in child mortality in Iraq after 1990 and during the period of the sanctions."<ref>Tim Dyson and Valeria Cetorelli, [https://gh.bmj.com/content/2/2/e000311.full Changing views on child mortality and economic sanctions in Iraq: a history of lies, damned lies and statistics] ''BMJ Global Health'' 2(2) (2017):e000311. Retrieved May 13, 2022.</ref> Albright addressed the controversy at length in a 2020 memoir: "In fact, the producers of ''60 Minutes'' were duped. Subsequent research has shown that Iraqi propagandists deceived international observers ... Per a 2017 article in the ''British Medical Journal of Global Health'', the data 'were rigged to show a huge and sustained—and largely non-existent—rise in child mortality ... to heighten international concern and so get the international sanctions ended.' ... This is not to deny that UN sanctions contributed to hardships in Iraq or to say that my answer to Stahl's question wasn't a mistake. They did, and it was. ... U.S. policy throughout the 1990s was to prevent Iraq from reconstituting its most dangerous weapons programs. Short of another war, UN sanctions were the best means for doing so."<ref>Madeleine Albright, ''Hell and Other Destinations: A 21st-Century Memoir'' (Harper, 2020, ISBN 978-0062802255).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Hillary Clinton campaign comment === | === Hillary Clinton campaign comment === | ||

| − | Albright supported Hillary Clinton during her | + | Albright supported [[Hillary Clinton]] during her 2016 presidential campaign. While introducing Clinton at a campaign event in [[New Hampshire]] ahead of that state's primary, Albright said, "There's a special place in hell for women who don't help each other" (a phrase Albright had used on several previous occasions in other contexts).<ref name="My Undiplomatic Moment" /> The remark was seen as a rebuke of younger women who supported Clinton's [[Primary election|primary]] rival, Senator [[Bernie Sanders]], which many women found "startling and offensive."<ref>Alan Rappeport, [https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/08/us/politics/gloria-steinem-madeleine-albright-hillary-clinton-bernie-sanders.html Gloria Steinem and Madeleine Albright Rebuke Young Women Backing Bernie Sanders] ''The New York Times'', February 8, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2022.</ref> In a ''[[New York Times]]'' [[op-ed]] published several days after the remark, Albright said: "I absolutely believe what I said, that women should help one another, but this was the wrong context and the wrong time to use that line. I did not mean to argue that women should support a particular candidate based solely on gender."<ref name="My Undiplomatic Moment">Madelein Albright, [https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/13/opinion/madeleine-albright-my-undiplomatic-moment.html My Undiplomatic Moment] ''The New York Times'', February 123, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2022.</ref> |

| − | == | + | == Legacy == |

| − | [[ | + | Upon her death on March 23, 2022, many political figures paid tribute to her as a trailblazer, including President [[Joe Biden]], former U.S. presidents [[Jimmy Carter]], [[Bill Clinton]], [[George W. Bush]], and [[Barack Obama]], and former British prime minister [[Tony Blair]], who stated: |

| + | <blockquote>Madeleine was one of the most remarkable people I ever had the privilege to work with. She had the sharpest of brains, the most lively conscience and the deepest compassion for humanity … She was an icon and an inspiration. I will miss her greatly. The world will miss her.<ref>Gloria Oladipo, [https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/mar/23/madeleine-albright-tributes-obama-bush-blair A trailblazer’: political leaders pay tribute to Madeleine Albright] ''The Guardian'', March 23, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | In his statement, Carter noted that: | ||

| + | <blockquote>She has been a highly effective and accomplished diplomat and a trailblazer as the first woman to serve as U.S. Secretary of State. Secretary Albright’s service to our country and world will inspire generations to come, and we extend our condolences to her family and to the many whose lives have been touched by this remarkable peacemaker.<ref>[https://www.cartercenter.org/news/pr/2022/statement-on-passing-of-madeleine-albright-032322.html Statement from Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter on the Passing of Madeleine Albright] ''The Carter Center''. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Her funeral, held at [[Washington National Cathedral]] on April 27, was attended by President Joe Biden, former presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, and former secretaries of state Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice,<ref>Peter Baker, [https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/27/us/politics/madeleine-albright-memorial.html At Madeleine Albright's Service, a Reminder of the Fight for Freedom] ''The New York Times'', April 27, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> President [[Vjosa Osmani-Sadriu]] and Prime Minister Albin Kurti of [[Kosovo]] as well as President of [[Georgia]] [[Salome Zourabichvili]] <ref>Joey Garrison, [https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2022/04/27/madeleine-albright-funeral-joe-biden-eulogy/7445361001/ 'Her story was America's story': Biden, Bill and Hillary Clinton, remember Madeleine Albright] ''USA Today'', April 27, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Awards and honors=== | |

| + | [[File:Medlin Olbrajt (Madeleine Albright) Square in Prishtinë, Kosovo.jpg|thumb|400px|Medlin Olbrajt Square in [[Pristina]], Kosovo named in honor of Madeleine Albright]] | ||

| + | Madeleine Albright received many awards and honors for her life of service. The Medlin Olbrajt (Madeleine Albright) Square in Prishtinë, Kosovo is named in her honor. | ||

| − | Albright | + | Albright held honorary degrees from [[Brandeis University]] (1996), the [[University of Washington]] (2002), [[Smith College]] (2003), [[Washington University in St. Louis]] (2003), [[University of Winnipeg]] (2005), the [[University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill]] (2007), [[Knox College (Illinois)|Knox College]] (2008), [[Bowdoin College]] (2013), [[Dickinson College]] (2014), and [[Tufts University]] (2015). |

| − | + | In 1998, Albright was inducted into the [[National Women's Hall of Fame]].<ref>[https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/madeleine-korbel-albright/ Albright, Madeleine Korbel] ''National Women's Hall of Fame''. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> Albright was the second recipient of the [[Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award]] presented by the [[Prague Society for International Cooperation]]. In March 2000 Albright received an Honorary Silver Medal of Jan Masaryk at a ceremony in [[Prague]] sponsored by the Bohemian Foundation and the [[Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs]].<ref>Madeleine K. Albrigh, [https://1997-2001.state.gov/statements/2000/000307.html Building a Europe Whole and Free] Remarks at Event Sponsored by the Bohemia Foundation, Prague, Czech Republic, March 7, 2000. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | Albright | + | Albright received the U.S. Senator [[H. John Heinz III]] Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by the [[Jefferson Awards for Public Service|Jefferson Awards Foundation]] (now ''Multiplying Good''), in 2001.<ref>[https://www.multiplyinggood.org/what-we-do/jefferson-awards/past-award-recipients Past Award Recipients] ''Multiplying Good''. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> |

| − | + | In 2010, she was inducted into the [[Colorado Women's Hall of Fame]].<ref>[https://www.cogreatwomen.org/project/madeleine-k-albright/ Madeleine K. Albright, PhD] ''Colorado Women's Hall of Fame''. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | She was awarded the [[Presidential Medal of Freedom]] by President [[Barack Obama]] in May 2012.<ref>Tom Cohen, [https://www.cnn.com/2012/05/29/us/medal-of-freedom/index.html Albright, Dylan among recipients of Presidential Medal of Freedom] ''CNN'', May 29, 2012. Retrieve May 16, 2022. </ref> | |

| − | Albright | + | Albright was selected for the inaugural 2021 ''[[Forbes]]'' 50 Over 50; made up of entrepreneurs, leaders, scientists, and creators who are over the age of 50.<ref>Elana Lyn Gross and Lisette Voytko, [https://www.forbes.com/50over50/ 50 over 50 The New Golden Age] ''Forbes'', June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == Major publications == |

| − | * | + | * ''Madam Secretary: A Memoir''. Miramax, 2003. ISBN 0786868430 |

| − | * | + | * ''The Mighty and the Almighty: Reflections on America, God, and World Affairs''. Harper, 2006. ISBN 978-0060892579 |

| − | * | + | * ''Memo to the President Elect: How We Can Restore America's Reputation and Leadership''. Harper, 2008. ISBN 978-0061351808 |

| − | * | + | * ''Read My Pins: Stories from a Diplomat's Jewel Box''. Melcher Media, 2009. ISBN 978-0060899189 |

| − | * | + | * ''Prague Winter: A Personal Story of Remembrance and War, 1937–1948''. Harper, 2012. ISBN 0062030310 |

| − | * | + | * ''Fascism: A Warning''. Harper, 2018. ISBN 978-0062802187 |

| − | * | + | * ''Hell and Other Destinations: A 21st-Century Memoir''. Harper, 2020. ISBN 978-0062802255 |

| − | == | + | == Notes == |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | + | * Albright, Madeleine. ''Madam Secretary: A Memoir''. Miramax, 2003. ISBN 0786868430 | |

| − | + | * Albright, Madeleine. ''The Mighty and the Almighty: Reflections on America, God, and World Affairs''. Harper, 2006. ISBN 978-0060892579 | |

| − | + | * Albright, Madeleine. ''Hell and Other Destinations: A 21st-Century Memoir''. Harper, 2020. ISBN 978-0062802255 | |

| − | * | + | * Blackman, Ann. ''Seasons of Her Life: A Biography of Madeleine Korbel Albright''. Scribner, 1998. ISBN 978-0684845647 |

| − | * | + | * Blood, Thomas. ''Madam Secretary: A Biography of Madeleine Albright''. St. Martin's Griffin, 1997. ISBN 978-0312304690 |

| − | * Blackman, Ann. ''Seasons of Her Life: A Biography of Madeleine Korbel Albright'' | + | * Clarke, Richard. ''Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror''. Free Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0743260459 |

| − | * | + | * Dallaire, Roméo. ''Shake Hands with the Devil''. Da Capo Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0786715107 |

| − | + | * Dobbs, Michael. ''Madeleine Albright: A twentieth-century odyssey''. Henry Holt and Co., 1999. ISBN 978-0805056594 | |

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 5, 2022. | |

| − | * [https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/people/albright-madeleine-korbel Biography] at the | + | * [https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/people/albright-madeleine-korbel Biography] at the ''United States Department of State'' |

| − | * [https://www.cfr.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/FY17%20Membership%20Roster.pdf Membership] at the | + | * [https://www.cfr.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/FY17%20Membership%20Roster.pdf Membership] at the ''Council on Foreign Relations'' |

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.wellesley.edu/PublicAffairs/Commencement/2007/MAlbright.html 2007 commencement speech, Wellesley College] | * [http://www.wellesley.edu/PublicAffairs/Commencement/2007/MAlbright.html 2007 commencement speech, Wellesley College] | ||

| − | * [https:// | + | * [http://chiasmos.uchicago.edu/events/albright.shtml Audio recording] of Albright's talk, "The Mighty and the Almighty," as part of the University of Chicago World Beyond the Headlines series. |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?178270-1/madame-secretary Interview with Albright on ''Madam Secretary'', September 19, 2003], ''C-SPAN'' |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?179031-3/madame-secretary-memoir Presentation by Albright on ''Madam Secretary'', November 8, 2003], ''C-SPAN'' |

| − | * | + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?186249-1/madame-secretary-memoir Presentation by Albright on ''Madam Secretary'', April 5, 2005], ''C-SPAN'' |

| + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?192476-1/after-words-madeleine-albright ''After Words'' interview with Albright on ''The Mighty and the Almighty'', May 13, 2006], ''C-SPAN'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?202509-4/memo-president-elect ''Washington Journal'' interview with Albright on ''Memo to the President Elect'', January 9, 2008], ''C-SPAN'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?203734-1/memo-president-elect Presentation by Albright on ''Memo to the President Elect'', January 11, 2008], ''C-SPAN'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?291113-1/read-pins Presentation by Albright on ''Read My Pins'', December 22, 2009], ''C-SPAN'' | ||

| + | *[https://www.c-span.org/video/?305741-1/after-words-madeleine-albright ''After Words'' interview with Albright on ''Prague Winter'', June 9, 2012], ''C-SPAN'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?449746-16/madeleine-albright-discusses-fascism-warning Discussion with Albright on ''Facism: A Warning'', September 1, 2018], ''C-SPAN'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.c-span.org/video/?475573-7/secretary-state-madeleine-albright-dies-84 Discussion with Albright on ''Hell and Other Destinations'', September 27, 2020], ''C-SPAN'' | ||

{{s-start}} | {{s-start}} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:54, 5 November 2022

| Madeleine Albright | |

Official portrait, ca. 1997 | |

64th United States Secretary of State

| |

| In office January 23, 1997 – January 20, 2001 | |

| Deputy | Strobe Talbott |

|---|---|

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Warren Christopher |

| Succeeded by | Colin Powell |

20th United States Ambassador to the United Nations

| |

| In office January 27, 1993 – January 21, 1997 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Edward J. Perkins |

| Succeeded by | Bill Richardson |

| Born | May 15 1937 Prague, Czechoslovakia |

| Died | March 23 2022 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Joseph Albright

(m. 1959; div. 1982) |

| Children | 3, including Alice P. Albright |

| Signature | |

Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright (born Marie Jana Korbelová; May 15, 1937 – March 23, 2022) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 64th United States secretary of state from 1997 to 2001. She was the first woman to hold the post.

Born in Prague, Czechoslovakia, Albright immigrated to the United States after the 1948 communist coup d'état when she was eleven years old. A member of the Democratic Party, she worked as an aide to Senator Edmund Muskie from 1976 to 1978, before serving as a staff member on the National Security Council under Zbigniew Brzezinski. She served in that position until 1981, when President Jimmy Carter left office.

After leaving the National Security Council, Albright joined the academic faculty of Georgetown University in 1982 and advised Democratic candidates regarding foreign policy. Following the 1992 presidential election, Albright helped assemble President Bill Clinton's National Security Council. She was appointed United States ambassador to the United Nations from 1993 to 1997, a position she held until elevation as secretary of state. Secretary Albright served in that capacity until President Clinton left office in 2001.

Albright was well regarded by her colleagues for her intelligence and effectiveness as a diplomat, despite making a number of controversial statements, which she later withdrew. As the first female Secretary of State she blazed a trail of accomplishment that has been followed by others, and widely recognized. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in May 2012.

Life

Early life in Europe

Albright was born Marie Jana Korbelová[1] in 1937 in the Smíchov district of Prague, Czechoslovakia.[2] Her parents were Josef Korbel, a Czech diplomat, and Anna Korbel (née Spieglová).[3] They also had a son, John,[4] and another daughter, Katherine, born in October 1942 after they had moved to London.[5]

When Marie Jana was born, her father was serving as a press-attaché at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Belgrade. At that time, Czechoslovakia had been independent for less than 20 years, having gained independence from Austria-Hungary after World War I. Her father was a supporter of Tomáš Masaryk and Edvard Beneš.[6] The signing of the Munich Agreement in September 1938—and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia by Adolf Hitler's troops—forced the family into exile because of their links with Beneš.[7]

The family moved to Britain in May 1939. Here her father worked for Beneš's Czechoslovak government-in-exile. Her family first lived on Kensington Park Road in Notting Hill, London—where they endured the worst of the Blitz—but later moved to Beaconsfield, then Walton-on-Thames, on the outskirts of London.[8] They kept a large metal table in the house, which was intended to shelter the family from the recurring threat of German air raids.[9] While in England, Marie Jana was one of the children shown in a documentary film designed to promote sympathy for war refugees in London.[10]

Josef and Anna converted from Judaism to Roman Catholicism in 1941 to avoid anti-Jewish persecution.[3] Marie Jana and her siblings were raised in the Catholic faith. In 1997, Albright said her parents never told her or her two siblings about their Jewish ancestry and heritage.[11][12]

When The Washington Post reported on Albright's Jewish ancestry shortly after she had become Secretary of State in 1997, Albright said that the report was a "major surprise."[13] Albright said that she did not learn until age 59 that both her parents were born and raised in Jewish families.[14] As many as a dozen of her relatives in Czechoslovakia—including three of her grandparents—had been murdered in the Holocaust.[11][12]

After the defeat of the Nazis in the European theatre of World War II and the collapse of Nazi Germany and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the Korbel family returned to Prague.[11] Korbel was appointed as press attaché at Czechoslovakian Embassy in Yugoslavia, and the family moved to Belgrade—then part of Yugoslavia—which was governed by the Communist Party. Korbel was concerned his daughter would be exposed to Marxism in a Yugoslav school, and so she was taught privately by a governess before being sent to the Prealpina Institut pour Jeunes Filles finishing school in Chexbres, on Lake Geneva in Switzerland.[15] She learned to speak French while in Switzerland and changed her name from Marie Jana to Madeleine.[16]

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took over the government in 1948, with support from the Soviet Union. As an opponent of communism, Korbel was forced to resign from his position. He later obtained a position on a United Nations delegation to Kashmir. He sent his family to the United States, by way of London, to wait for him when he arrived to deliver his report to the UN Headquarters, then located in Lake Success, New York.[17]

In the United States

The Korbel family emigrated from the United Kingdom on the SS America, departing Southampton on November 5, 1948, and arriving at Ellis Island in New York Harbor on November 11, 1948.[18] The family initially settled in Great Neck on the North Shore of Long Island and Korbel applied for political asylum, arguing that as an opponent of Communism, he was under threat in Prague.[19] Korbel stated:

I cannot, of course, return to the Communist Czechoslovakia as I would be arrested for my faithful adherence to the ideals of democracy. I would be most obliged to you if you could kindly convey to his Excellency the Secretary of State that I beg of him to be granted the right to stay in the United States, the same right to be given to my wife and three children.[20]

With the help of Philip Moseley, a Russian language professor at Columbia University in New York City, Korbel obtained a position on the staff of the political science department at the University of Denver in Colorado.[21] He became dean of the university's school of international relations, and later taught future U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. The school was named the Josef Korbel School of International Studies in 2008 in his honor.[6]

Madeleine Korbel spent her teen years in Denver and in 1955 graduated from the Kent Denver School in Cherry Hills Village, a suburb of Denver. She founded the school's international relations club and was its first president.[22] She attended Wellesley College, in Massachusetts, on a full scholarship, majoring in political science, and graduated in 1959.[23] The topic of her senior thesis was Zdeněk Fierlinger, a former Czechoslovakian prime minister.[24] She became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1957, and joined the College Democrats of America.[25]

While home in Denver from Wellesley, Korbel worked as an intern for The Denver Post. There she met Joseph Albright. He was the nephew of Alicia Patterson, owner of Newsday and wife of philanthropist Harry Frank Guggenheim.[26] Korbel converted to the Episcopal Church at the time of her marriage.[11][12] The couple were married in Wellesley in 1959, shortly after her graduation.[23] They lived in Rolla, Missouri, while Joseph completed his military service at nearby Fort Leonard Wood. During this time, Albright worked at The Rolla Daily News.[27]

The couple moved to Joseph's hometown of Chicago, Illinois, in January 1960. Joseph worked at the Chicago Sun-Times as a journalist, and Albright worked as a picture editor for Encyclopædia Britannica.[28] The following year, Joseph Albright began work at Newsday in New York City, and the couple moved to Garden City on Long Island. That year, she gave birth to twin daughters, Alice Patterson Albright and Anne Korbel Albright. The twins were born six weeks premature and required a long hospital stay. As a distraction, Albright began Russian language classes at Hofstra University in the Village of Hempstead nearby.[29]

In 1962, the family moved to Washington, D.C., where they lived in Georgetown. Albright studied international relations and continued in Russian at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, a division of Johns Hopkins University in the capital.[30]

Joseph's aunt Alicia Patterson died in 1963 and the Albrights returned to Long Island with the notion of Joseph taking over the family newspaper business.[31] Albright gave birth to another daughter, Katharine Medill Albright, in 1967. She continued her studies at Columbia University's Department of Public Law and Government.[32] She earned a certificate in Russian from the Russian Institute (now Harriman Institute),[33] an M.A. and a PhD, writing her master's thesis on the Soviet diplomatic corps and her doctoral dissertation on the role of journalists in the Prague Spring of 1968. She earned her doctorate in 1975.[34] She also took a graduate course given by Zbigniew Brzezinski, who later became her boss at the U.S. National Security Council.[35]

In the early 1980s, upon her return to Washington after traveling in Poland to research the Solidarity movement, her husband announced his intention to divorce her so that he could pursue a relationship with another woman.[36]

She had a long and distinguished career as a diplomat and political scientist, and served as the 64th United States Secretary of State from 1997 to 2001.

Albright died from cancer in Washington, D.C., on March 23, 2022, at the age of 84.[37]

Career

Early career

Albright returned to Washington, D.C., in 1968, commuting to Columbia University for her Doctor of Philosophy, and began fund-raising for her daughters' school, which led to several positions on education boards.[38] She was eventually invited to organize a fund-raising dinner for the 1972 presidential campaign of U.S. Senator Ed Muskie of Maine.[39] This association with Muskie led to a position as his chief legislative assistant in 1976.[40] However, after the 1976 U.S. presidential election of Jimmy Carter, Albright's former professor Brzezinski was named National Security Advisor, and recruited Albright from Muskie in 1978 to work in the West Wing as the National Security Council's congressional liaison.[40]

Following Carter's loss in 1980 to Ronald Reagan, Albright moved on to the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where she was given a grant for a research project. She chose to write on the dissident journalists involved in Poland's Solidarity movement, then in its infancy but gaining international attention.[41] She traveled to Poland for her research, interviewing dissidents in Gdańsk, Warsaw, and Kraków.[42]

Albright joined the academic staff at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., in 1982, specializing in Eastern European studies.[43] She also directed the university's program on women in global politics.[44] She served as a major Democratic Party foreign policy advisor, briefing vice-presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro in 1984 and presidential candidate Michael Dukakis in 1988 (both campaigns ended in defeat).[45] In 1992, Bill Clinton returned the White House to the Democratic Party, and Albright was employed to handle the transition to a new administration at the National Security Council.[46] In January 1993, Clinton nominated her to be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, her first diplomatic posting.[47]

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations

Albright was appointed Ambassador to the United Nations, a Cabinet-level position, shortly after Clinton was inaugurated, presenting her credentials on February 9, 1993. During her tenure at the U.N., she had a rocky relationship with the U.N. secretary-general, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, whom she criticized as "disengaged" and "neglect[ful]" of genocide in Rwanda.[48] She wrote: "My deepest regret from my years in public service is the failure of the United States and the international community to act sooner to halt these crimes."[49]

In Shake Hands with the Devil, Roméo Dallaire writes that in 1994, in Albright's role as the U.S. Permanent Representative to the U.N., she avoided describing the killings in Rwanda as "genocide" until overwhelmed by the evidence.[50] She was instructed to support a reduction or withdrawal (something which never happened) of the U.N. Assistance Mission for Rwanda but was later given more flexibility.[51] Albright later remarked in PBS documentary Ghosts of Rwanda that "it was a very, very difficult time, and the situation was unclear. You know, in retrospect, it all looks very clear. But when you were [there] at the time, it was unclear about what was happening in Rwanda."[52]

Also in 1996, after Cuban military pilots shot down two small civilian aircraft flown by the Cuban-American exile group Brothers to the Rescue over international waters, she announced, "This is not cojones. This is cowardice."[53] The line endeared her to President Clinton, who said it was "probably the most effective one-liner in the whole administration's foreign policy."[54]

In 1996, Albright entered into a secret pact with Richard Clarke, Michael Sheehan, and James Rubin to overthrow U.N. secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who was running unopposed for a second term in the 1996 selection. After 15 U.S. peacekeepers died in a failed raid in Somalia in 1993, Boutros-Ghali became a political scapegoat in the United States.[55] They dubbed the pact "Operation Orient Express" to reflect their hope that other nations would join the United States.[56] Although every other member of the United Nations Security Council voted for Boutros-Ghali, the United States refused to yield to international pressure to drop its lone veto. After four deadlocked meetings of the Security Council, Boutros-Ghali suspended his candidacy and became the only U.N. secretary-general ever to be denied a second term. The United States then fought a four-round veto duel with France, forcing it to back down and accept Kofi Annan as the next secretary-general. In his memoirs, Clarke said that "the entire operation had strengthened Albright's hand in the competition to be Secretary of State in the second Clinton administration."[56]

Secretary of State

When Clinton began his second term in January 1997, he required a new Secretary of State, as incumbent Warren Christopher was retiring. The top level of the Clinton administration was divided into two camps on selecting the new foreign policy. Outgoing Chief of Staff Leon Panetta favored Albright, but a separate faction argued, "anybody but Albright," with Sam Nunn as its first choice. Albright orchestrated a campaign on her own behalf that proved successful.[57] When Albright took office as the 64th U.S. Secretary of State on January 23, 1997, she became the first female U.S. Secretary of State and the highest-ranking woman in the history of the U.S. government at the time of her appointment.[58] Not being a natural-born citizen of the U.S., she was not eligible as a U.S. presidential successor.[59]

During her tenure, Albright considerably influenced American foreign policy in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Middle East. According to Albright's memoirs, she once argued with Colin Powell for the use of military force by asking, "What's the point of you saving this superb military, Colin, if we can't use it?"[60]

As Secretary of State, she represented the U.S. at the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong on July 1, 1997. She along with the British contingents boycotted the swearing-in ceremony of the Chinese-appointed Hong Kong Legislative Council, which replaced the elected one.[61] In October 1997, she voiced her approval for national security exemptions to the Kyoto Protocol, arguing that NATO operations should not be limited by controls on greenhouse gas emissions, and hoped that other NATO members would also support the exemptions at the Third Conference of the Parties in Kyoto, Japan.[62]

According to several accounts, Prudence Bushnell, U.S. Ambassador to Kenya, repeatedly asked Washington for additional security at the embassy in Nairobi, including in a letter directly addressed to Albright in April 1998. Bushnell was ignored.[63] In Against All Enemies, Richard Clarke writes about an exchange with Albright several months after the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania were bombed in August 1998. "What do you think will happen if you lose another embassy?" Clarke asked. "The Republicans in Congress will go after you." "First of all, I didn't lose these two embassies," Albright shot back. "I inherited them in the shape they were."[56]

In 1998, at the NATO summit, Albright articulated what became known as the three "D"s of NATO, "which is no diminution of NATO, no discrimination and no duplication – because I think that we don't need any of those three "D"s to happen."[64]

Albright became one of the highest level Western diplomats ever to meet Kim Jong-il, the then-leader of communist North Korea, during an official state visit to that country in 2000.[65]

On January 8, 2001, in one of her last acts as Secretary of State, Albright made a farewell call to Kofi Annan and said that the U.S. would continue to press Iraq to destroy all its weapons of mass destruction as a condition of lifting economic sanctions, even after the end of the Clinton administration on January 20, 2001.[66]

Post-Clinton administration

Following Albright's term as Secretary of State, Czech president Václav Havel spoke openly about the possibility of Albright succeeding him. Albright was reportedly flattered, but denied ever seriously considering the possibility of running for office in her country of origin.[67]

Albright was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2001. Also that year, she founded the Albright Group, an international strategy consulting firm based in Washington, D.C. that later become the Albright Stonebridge Group. Affiliated with the firm is Albright Capital Management, which was founded in 2005 to engage in private fund management related to emerging markets.[68]