Spearfishing

Spearfishing is a form of fishing that has been popular throughout the world for centuries. Early civilizations are familiar with the custom of spearing fish out of rivers and streams using sharpened sticks as a means of catching food.

Spearfishing today uses more modern and effective elastic- or pneumatic-powered spearguns and slings to strike the hunted fish.

Spearfishing may be done using free-diving, snorkeling, or scuba diving techniques. However, spearfishing while using SCUBA or other artificial breathing apparatus is frowned upon in some locations and is illegal in many others. Because of the belief of lack of sport in some modern spearfishing techniques, the use of mechanically-powered spearguns is outlawed in some jurisdictions.

Spearfishing in the past has been detrimental to the environment when species unafraid or unused to divers were targeted excessively. However, it is also highly selective and has low amount of by-catch; therefore with education and proper regulations spearfishing can be an ecologically sustainable form of fishing.

The very best free-diving spearfishers can hold their breath for durations of 2-4 minutes and dive to depths of 40 or even 60 meters (about 130 to 200 feet). However, dives of approximately 1 minute and 15 or 20 meters (about 50 to 70 feet) are more common for the average experienced spearfisher.

History

Spearfishing with barbed poles (harpoons) was widespread in paleolithic times.[1] Cosquer cave in Southern France contains cave art over sixteen thousand years old, including drawings of seals which appear to have been harpooned.

There are references to fishing with spears in ancient literature; though, in most cases, the descriptions do not go into detail. An early example from the Bible in Job 41:7: Canst thou fill his skin with barbed irons? or his head with fish spears?

The Greek historian Polybius (ca. 203 B.C.E. – 120 B.C.E.), in his Histories, describes hunting for swordfish by using a harpoon with a barbed and detachable head.[2]

Oppian of Corycus, a Greek author wrote a major treatise on sea fishing, the Halieulica or Halieutika, composed between 177 and 180 C.E. This is the earliest such work to have survived intact to the modern day. Oppian describes various means of fishing including the use of spears and tridents.

In a parody of fishing, a type of gladiator called retiarius was armed with a trident and a casting-net. He would fight against the murmillo, who carried a short sword and a helmet with the image of a fish on the front.

Copper harpoons were known to the seafaring Harappans well into antiquity. Early hunters in ancient India include the Mincopie people, aboriginal inhabitants of India's Andaman and Nicobar islands, who have used harpoons with long cords for fishing since early times.

Traditional spear fishing

Spear fishing is an ancient method of fishing and may be conducted with an ordinary spear or a specialized variant such as an eel spear[3][4] or the trident. A small trident type spear with a long handle is used in the American South and Midwest for gigging bullfrogs with a bright light at night, or for gigging carp and other fish in the shallows.

Traditional spear fishing is restricted to shallow waters, but the development of the speargun has made the method much more efficient. With practice, divers are able to hold their breath for up to four minutes and sometimes longer; of course, a diver with underwater breathing equipment can dive for much longer periods.

Modern spear fishing

In the 1920s, sport spearfishing without a breathing apparatus became popular on the Mediterranean coast of France and Italy. At first, divers used no more aid than ordinary watertight swimming goggles, but it led to development of the modern diving mask, swimfin and snorkel. Modern scuba diving had its genesis in the systematic use of rebreathers for diving by Italian sport spearfishers during the 1930s. This practice came to the attention of the Italian Navy, which developed its frogman unit, which affected World War II.[5]

During the 1960s, attempts were made to have spearfishing recognized as an Olympic sport. This didn't happen. Instead, two organizations, the International Underwater Spearfishing Association (IUSA) and the International Bluewater Spearfishing Records Committee (IBSRC), maintain lists of world records by species and offer rules to insure that any world record setting fish is caught under fair conditions. Spearfishing is illegal in many bodies of water, and some locations only allow spearfishing during certain seasons.

Purposes of spearfishing

People spearfish for sport, for commerce or as subsistence. In tropical seas, some natives spearfish in a snorkeling kit for a living, often using home-made kit.

Spearfishing and conservation

Spearfishing has been implicated in local extirpation of many larger species, including the Goliath grouper on the Caribbean island of Bonaire, the Nassau grouper in the barrier reef off the coast of Belize, the giant black sea bass in California, and others.[6]

Types of spearfishing

The methods and locations freedive spearfishers use vary greatly around the world. This variation extends to the species of fish sought and the gear used.

Shore diving

Shore diving is perhaps the most common form of spearfishing and simply involves entering and exiting the sea from beaches or headlands and hunting around ocean architecture, usually reef, but also rocks, kelp or sand. Usually shore divers hunt between 5 and 25 meters (about 16 to 83 feet) depth, though it depends on location. In some locations in the South Pacific, divers can experience huge drop-offs from 5 meters (16 feet) up to 30 or 40 meters (98 to 131 feet) very close to the shore line. Sharks and reef fish can be abundant in these locations. In more subtropical areas, sharks may be less common, but other challenges face the shore diver, such as entering and exiting the water in the presence of big waves. Headlands are favored for entry because of their proximity to deeper water, but timing entries and exits is important so the diver does not get pushed onto rocks by waves. Beach entry can be safer, but more difficult due the need to consistently dive through the waves until the surf line is crossed.

Shore dives can produce a mixed bag of fish, mainly reef fish, but ocean going pelagic fish are caught from shore dives too, and can be specifically targeted.

Shore diving can be done with trigger-less spears such as pole spears or Hawaiian slings, but more commonly triggered devices such as spearguns. Speargun setups to catch and store fish include speed rigs, fish stringers.

The use of catch bags worn close to the body is discouraged because the bag can inhibit movement, especially descent or ascent on deeper freedives. Moreover, in waters known to contain sharks, it is positively dangerous and can greatly increase the risk of attack. The better option is to tow a float behind, to which is attached a line onto which a catch can be threaded. Tying the float line to the speargun can be of great assistance in the event of a large catch, or if the speargun should be dropped or knocked out of reach.

Boat diving

Boats, ships or even kayaks can be used to access off shore reefs or ocean structure such as pinnacles. Man made structures such as oil rigs and FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices) are also fished. Sometimes a boat is necessary to access a location that is close to shore, but inaccessible by land.

Methods and gear used for diving from a boat diving are similar to shore diving or blue water hunting depending on the prey sought. Care must be taken with spearguns in the cramped confines of a small boat, and it is recommended that spear guns are never loaded on the boat.

Boat diving is practiced worldwide. Hot spots include the northern islands of New Zealand (yellow tail kingfish), Gulf of Florida oil rigs (cobia, grouper) and the Great Barrier Reef (wahoo, dog-tooth tuna). FADS are targeted worldwide, often specifically for mahi-mahi (dolphin fish). The deepwater fishing grounds off Cape Point, (Cape Town, South Africa) have become popular with trophy hunting, freediving spearfishers in search of Yellowfin Tuna.

Blue water hunting

Blue water hunting is the area of most interest to elite spearfishers, but has increased in popularity generally in recent years. It involves accessing usually very deep and clear water and trolling, chumming for large pelagic fish species such as marlin, tuna, or giant trevally. Blue water hunting is often conducted in drifts; the boat driver will drop one or more divers and allow them to drift in the current for up to several kilometers before collecting them. Blue water hunters can go for hours without seeing any fish, and without any ocean structure or a visible bottom the divers can experience sensory deprivation. It can be difficult to determine the true size of a solitary fish when sighted due to the lack of ocean structure for comparison. One technique to overcome this is to note the size of the fish's eye in relation to its body - large examples of their species will have a relatively smaller eye.

Notably, blue water hunters make use of breakaway rigs and large multi band wooden guns to catch and subdue their prey. If the prey is large and still has fight left after being subdued, a second gun can be used to provide a kill shot at a safe distance from the fish. This is acceptable to IBSRC and IUSA regulations as long as the spearfisher loads it himself in the water.

Blue water hunting is conducted world wide, but notable hot spots include South Africa (yellowfin tuna) and the South Pacific (dog-tooth snapper). Blue water pioneers like Jack Prodanavich and Hal Lewis of San Diego were some of the first to go after large species of fast moving fish like tuna.

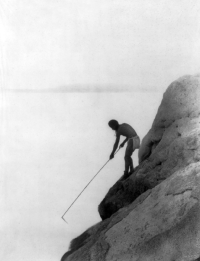

Without diving

These methods have been used for thousands of years. A fisher wades in shallow salt or fresh water with a hand spear. The fisher must account for optical refraction at the water's surface, which makes the fish appear to be further away. By experience, the fisher learns to aim lower to hit the target. Calm and shallow waters are favored for spearing fish from above the surface.[7]

Spearfishing can also be done directly from a boat, and can have similarities to bowfishing. See gigging.

Equipment

This is a list of equipment commonly used in spearfishing. Not all of it is necessary and spearfishing is often practiced with minimal gear.

- Speargun

- A speargun is a gun designed to fire a spear, usually underwater to catch fish. Spearguns come in a wide variety. Some use rubber bands, some use carbon dioxide gas or air. All spearguns have a trigger mechanism that holds a spear in place along the barrel.

- Polespear

- Pole spears, or hand spears, consist of a long shaft with point at one end and an elastic loop at the other for propulsion. They also come in a wide variety, from aluminum or titanium metal, to fiberglass or carbon fiber. Often they are screwed together from smaller pieces or able to be folded down for ease of transport.

- Hawaiian slings

- Hawaiian slings consist of an elastic band attached to a tube, through which a spear is launched.

- Wet Suit

- Wetsuits designed specifically for spearfishing are often two-piece (jacket and 'long-john' style pants) and have camouflage patterns, blue for open ocean, green or brown for reef hunting. Commonly they have a pad on the chest to aid in loading spearguns.

- Weight belt or weight vest

- These are used to compensate for wetsuit buoyancy and help the diver descend to depth.

- Fins

- Fins for freedive spearfishing are much longer than those used in SCUBA to aid in fast ascent.

- Knife

- A knife should always be carried as a safety precaution in case of the diver becoming tangled in his spear or float line. It can also be used as an "iki jime" or kill spike. Iki jime is a Japanese term and is a method traditionally used by Japanese fishermen. Killing the fish quickly is believed to improve the flavor of the flesh by limiting the buildup of adrenaline and blood in the fish's muscles.

- Kill spike

- In lieu of a knife, a sharpened metal spike can be used to kill the fish quickly and humanely upon capture. This action reduces interest from sharks by stopping the fish from thrashing.

- Snorkel and diving mask

- Spearfishing snorkels and diving masks are similar to those used for scuba diving. Spearfishing masks sometimes have mirrored lenses that prevent fish from seeing the spearfisher's eyes tracking them. Mirrored lenses appear to fish as one big eyeball, so head movements can still spook the fish.

- Buoy or float

- A buoy is usually tethered to the spearfisher's speargun or directly to the spear. A buoy helps to subdue large fish. It can also assist in storing fish, but is more importantly used as a safety device to warn boat drivers there is diver in the area.

- Floatline

- A floatline connects the buoy to the speargun. Often made from woven plastic, they also be mono-filament encased in an airtight plastic tube, or made from stretchable bungee cord.

- Gloves

- Gloves are a value to spearfisherman that desire to maintain a sense of safety or access more dangerous areas, such as those between coral, that could otherwise not be reached without use of the hands. They also aid in loading the bands on rubber powered speargun.

Management of Spearfishing

Spearfishing is intensively managed throughout the world.

In Australia it is a recreational-only activity and generally only breath-hold free diving. There are numerous restriction placed by the Government such as Marine Protected Areas, Closed Areas, Protected Species, size/bag limits and equipment.

The peak recreational body is the Australian Underwater Federation. The vision of this group is "Safe, Sustainable, Selective, Spearfishing" and the AUF provides membership, advocacy and organizes competitions. [8]

Because of its relatively long coastline compared to its population, Norway has one of the most liberal spearfishing rules in the northern hemisphere, and spearfishing with scuba gear is a widespread activity among recreational divers. Restrictions in Norway are limited to anadrome species, like Atlantic salmon, sea trout, and lobster.[9]

In Mexico a regular fishing permit allows for Spearfishing, but not for electro-mechanical types of spearguns.[10]

Spearfishing techniques

One of the best tricks a spearfisherman can take advantage of is a fish's curiosity. Fish see their world with their eyes and with vibrations picked up by their lateral line. Experienced spearfishermen take advantage of this by moving very slowly in the water, and by using weights to carry them to the bottom rather than kicking of fins to minimize vibration.

Once on the bottom or in sight of a fish a spearfisherman will remain perfectly still, and lack of vibration in the water will usually cause the fish to come within spear range to investigate. Experienced shore spearfishermen will travel along the shoreline and prepare for an entrance to the water and enter and go straight to the bottom for as long as they can hold their breath.

Any large fish in the area will usually come to investigate the appearance and then disappearance of something, as no picture is available to their lateral line of a non moving object. Any rocks or other objects on the bottom that the spearfisherman can get close to will further disguise his appearance and warrant closer investigation by fish within 40 yards. Exiting the water and moving 40 yards down the shore usually produces another shot at a big one.

Experienced divers will carry several small pieces of coral or shells and when a fish is reluctant to come into spear range, rubbing or clicking of these usually draws them closer. Throwing up sand also will bring a fish closer and helps to camouflage the diver. Contact with coral should be avoided as this may damage the reef. Blue water divers will float on the surface 100 yards from their boat and continue to rap a dive knife or a softer object against their spear gun until a big one comes to investigate.

In areas where many holes are available for a fish to hide in, a strong swimmer can clip his gun to his belt, and force a fish into a hole by swimming full speed and slapping his cupped hands on the surface with each stroke. Another shoreline technique for the big ones is to spear fish that are favorite prey of the desired species or collect the seaweed, mussels, etc. that they eat and chum them into the area.

Some think chumming the water is dangerous as it will draw sharks, but many big predator fish travel with reef sharks, and the instances of spearfisherman being attacked is a very low percentage of the total number of shark attacks. Sharks are like dogs,: if you cower from a bad dog, it will bite you, but if you stand your ground with a big stick, you can usually back it down.

Spearfishing in areas with many sharks larger than 8 feet and of aggressive species does not require chumming as these areas are plentiful in big fish that are not used to seeing spear fisherman. Care needs to be taken in these areas to stay out of areas where blood from a kill is in the water.

Spearfishing for the future

Spearfishing is one of the oldest methods of fishing. The equipment developed from a simple hand held spear to the modern speargun. The method also developed from spearing from above water to spearing in water with sophisticated diving equipment. While technology has aided spearfishing, without proper fishery management, technology can destroy spearfishing itself. Management should include regulations on periods of fishing, locations, species and size of fish, and methods of fishing.

In addition to these direct factors, fishery management should also look into broader environmental issues, which includes industrial waste management, water and air pollution, and other environmental issues.

Notes

- ↑ Dale Guthrie, The Nature of Paleolithic Art (University of Chicago Press, 2005, ISBN 0226311260), 298.

- ↑ Polybius, "Fishing for Swordfish", Histories Book 34.3 (Evelyn S. Shuckburgh, translator). (London, New York: Macmillan, 1889. Reprint Bloomington, 1962.)

- ↑ Image of an eel spear. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Spear fishing for eels. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ D. Quick, A History Of Closed Circuit Oxygen Underwater Breathing Apparatus (Royal Australian Navy, School of Underwater Medicine. RANSUM-1-70. 1970.)

- ↑ Callum Roberts, The Unnatural History of the Sea (Island Press, 2007), 238.

- ↑ Otto Gabriel and Andres von Brandt, Fish Catching Methods of the World (Blackwell Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0852382804), 53-54.

- ↑ Australian Underwater Federation. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Spearfishing in Norway Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ CONAPESCA SAN DIEGO - Sportfishing regulations, Conapesca Mexico San Diego Office.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barada, Bill. Underwater Hunting; Its Techniques and Adventures. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969.

- Curtis, Val. Regulatory Guide to Spear Fishing. Brisbane: Queensland Fisheries Service, 1978.

- Gabriel, Otto, and Andres von Brandt. Fish Catching Methods of the World. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Pub, 2005.

- Guthrie, Dale. The Nature of Paleolithic Art. University of Chicago Press, 2005. ISBN 0226311260

- Ivanović, Ivan S. Modern Spearfishing. New York: Barnes, 1955.

- Jones, Len, and Jessica Jones. Encounters with Sharks, Dolphins and Big Fish. Durban: L. Jones, 2003.

- Jones, Len. Len Jones' Guide to Freedive Spearfishing. Woolloongabba, Qld: Adrenaline Spearfishing Supplies, 2002.

- Jones, Len. Len Jones' Guide to Spearfishing. Tauranga, N.Z.: Fishing Guide Books], 2001.

- Maas, Terry. Bluewater Hunting and Freediving. Ventura, Calif: BlueWater Freedivers, 1998.

- Polybius, Fridericus Hultsch, and Evelyn S. Shuckburgh. The Histories of Polybius. London and New York: Macmillan and Co, 1889.

- Quick, D. A History Of Closed Circuit Oxygen Underwater Breathing Apparatus. Royal Australian Navy, School of Underwater Medicine. RANSUM-1-70. 1970.

- Roberts, Callum. The Unnatural History of the Sea. Washington, DC: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2007.

- Schenck, Hilbert van Nydeck, and Henry Way Kendall. Shallow Water Diving and Spearfishing. Cambridge, Md: Cornell Maritime Press, 1954.

- Smith, Adam K., Ben Cropp, and Terry Maas. Underwater Fishing: In Australia and New Zealand. Narre Warren, Vic: Mountain Ocean & Travel Publications, 2000.

- Tanabe, Sonny. Spearfishing on the Island of Hawaiʻi: A Pictorial History. Honolulu: Editions Limited, 2007.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.