Pancreatitis

| Pancreatitis Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | K85, K86.0-K86.1 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 577.0-577.1 |

| OMIM | 167800 |

| DiseasesDB | 24092 |

| eMedicine | emerg/354 |

| MeSH | D010195 |

Pancreatitis is an inflammation of the pancreas, an important organ for digestion and control of circulating levels of glucose. Acute pancreatitis involves a sudden inflammation of the pancreas, while chronic pancreatitis is a long-standing, slowly progressing inflammation of the pancreas.

Pancreatitis represents a disruption of the normal complex coordination in the body whereby digestive enzymes, which normally are active after leaving the pancreas, become prematurely activated and begin their functions while still in the pancreas, digesting the pancreatic tissue itself.

Among the various causes, one of the most prevalent is a preventable one: alcoholism. In addition, the abuse of alcohol can lead to a deteriorating condition without strong symptoms, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment.

Both acute pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis can be fatal, although acute pancreatitis is more easily treatable and with fuller recovery.

Overview

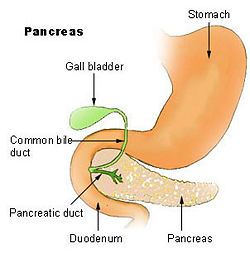

The pancreas is a glandular organ found in vertebrates near the stomach and small intestine. It is one of the few organs that has both an exocrine and an endocrine function. The pancreas' exocrine function involves the secretion of digestive enzymes (trypsin, lipase, chymotrypsin, etc., and bicarbonate into the small intestine, to which it is linked by pancreatic duct. Its endocrine function involves the regulation of blood sugar levels by secreting the hormones insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin directly into the blood. Another hormone, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) affects gastrointestinal functioning (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

When the pancreas is damaged in some way, the digestive enzymes may begin to digest the pancreatic tissue (autodigestion), resulting in inflammation. Inflammation is a localized protective response of a body's living tissue to injury, infection, irritation, or allergy and is characterized by the following quintet: redness (rubor), heat (calor), swelling (tumor), pain (dolor), and dysfunction of the organs involved (functio laesa).

Types

There are two basic forms of pancreatitis, which are different in causes and symptoms, and require different treatment.

Acute pancreatitis occurs when there is a sudden inflammation of the pancreas. If treated, most patients recover fully and in about 90 percent of the cases the symptoms disappear within a week after treatment (Carson-DeWitt 2002). Most cases are self-correcting once the damaging agent is eliminated and then there is no re-occurence (Smith 2008). Death occurs in less than five percent of cases and generally because of complications, such as infection or extensive tissue destruction and hemorrhage (Smith 2008).

Chronic pancreatitis occurs when the disease becomes self-perpetuating and either results in periodic or sporadic attacks similar to the acute form or is persistent and causes few symptoms while much of the pancreas is destroyed (Smith 2008; Carson-DeWitt 2002). As many as fifty percent of cases of chronic pancreatitis are fatal and the pancreas is permanently impaired, with damage to the tissue (Smith 2008; Carson-DeWitt 2002).

The basic mechanism of pancreatitis is that some cause results in many of the extremely potent enzymes produced by the pancreas, which normally become active only after they are passed into the duodenum, become prematurely activated so they begin their digestive functions within the pancreas. That is, the pancreas begins to digest itself. This causes a cycle of inflammation, including swelling and loss of function, and digestion of the blood vessels within the pancreas leads to bleeding. The leaky, eroded blood vessels also allow activated enzymes to gain access to the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

Causes

There are a number of causes of pancreatitis, with the most common being gallbladder disease (biliary tract disease) and alcoholism (Smith 2008; Carson-DeWitt 2002). The exact biochemical processes responsible for pancreatitis are not known, and though a variety of damaging agents have been identified, as many as 30 percent of cases lack a clear cut cause (known as idiopathic pancreatitis) (Smith 2008). However, for those cases in which the cause is detectable, over 80 percent of all cases of hospitalization for acute and chronic pancreatitis in Europe and the United States are tied to these two diseases (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

The most common cause of acute pancreatitis is gallstones in the common bile duct. Such obstructions can back up the bile into the pancreatic duct and trigger pancreatitis. This seldom leads to chronic pancreatitis because the obstruction can be cleared by surgeons. Alcohol is the most common toxic agent and while heavy drinkers rarely develop acute pancreatitis, a long history of steady drinking is the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis by far (Smith 2008).

Less common causes of pancreatitis include traumatic injury (especially damage by the steering wheel or seat belt during an automobile accident); damage during abdominal surgery or endoscopic procedures in the small intestine; viral infections (eg., mumps), hypertriglyceridemia (but not hypercholesterolemia, and only when triglyceride values exceed 1500 mg/dl (16 mmol/L)); hypercalcemia (high blood levels of calcium); viral infection (e.g. mumps), vasculitis (in other words, inflammation of the small blood vessels within the pancreas); and autoimmune pancreatitis. Pregnancy can also cause pancreatitis, but in some cases the development of pancreatitis is probably just a reflection of the hypertriglyceridemia that often occurs in pregnant women. Pancreas divisum, a common congenital malformation of the pancreas may underlie some cases of recurrent pancreatitis. Drugs (such as estrogens, tetracycline, sulfonamides), etc.) cause about five percent of all diagnosed cases of pancreatitis (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

The more mundane, but far more common causes of pancreatitis, as mentioned above, must always be considered first. However, the known porphyrinogenicity of many drugs, hormones, alcohol, chemicals, and the association of porphyrias with autoimmune disorders and gallstones do not exclude the diagnosis of heme disorders when these explanations are used. A primary medical disorder, including an underlying undetected inborn error in metabolism, supersedes a secondary medical complication or explanation.

Autoimmune disorders, lipid disorders, gallstones, drug reactions, and pancreatitis itself are not primary medical disorders.

A useful mnemonic for remembering the causes of acute pancreatitis is (I get smashed):

- Idiopathic

- Gallstones

- Ethanol

- Trauma

- Steroids

- Mumps

- Autoimmune causes

- Scorpion venom

- Hyperlipidaemias

- ERCP (Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, resulting in injuries)

- Drugs (such as Azathioprine)

Porphyrias

Acute hepatic porphyrias, including acute intermittent porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria, and variegate porphyria, are genetic disorders that can be linked to both acute and chronic pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis has also occurred with erythropoietic protoporphyria.

Conditions that can lead to gut dysmotility predispose patients to pancreatitis. This includes the inherited neurovisceral porphyrias and related metabolic disorders. Alcohol, hormones, and many drugs including statins are known porphyrinogenic agents. Physicians should be on alert concerning underlying porphyrias in patients presenting with pancreatitis and should investigate and eliminate any drugs that may be activating the disorders.

Still, notwithstanding their potential role in pancreatitis, the porphyrias (as a group or individually) are considered to be rare disorders. However, since there are no systematic studies to determine the actual incidence of latent dominantly-inherited porphyrias in the world population, and there is DNA or enzyme evidence of high rates of latency of classic textbook symptoms in families where porphyrias have been detected, and since the technology is not developed to detect all latent porphyrias, the diagnosis of underlying inborn errors of metabolism impacting heme should not be routinely eliminated in pancreatitis.

Medications

Many medications have been reported to cause pancreatitis. Some of the more common ones include the AIDS drugs DDI and pentamidine, diuretics such as furosemide and hydrochlorothiazide, the chemotherapeutic agents L-asparaginase and azathioprine, and estrogen (birth control pills). Just as is the case with pregnancy-associated pancreatitis, estrogen may lead to the disorder because of its effect of raising blood triglyceride levels.

Genetics

Hereditary pancreatitis may be due to a genetic abnormality that renders trypsinogen active within the pancreas, which in turn leads to digestion of the pancreas from the inside.

Pancreatic diseases are notoriously complex disorders resulting from the interaction of multiple genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors.

Three candidates for genetic testing are currently under investigation:

- Trypsinogen mutations (Trypsin 1)

- Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Gene (CFTR) mutations

- SPINK1, which codes for PSTI, a specific trypsin inhibitor.

Symptoms and signs

Severe upper abdominal pain, with radiation through to the back, is the hallmark of pancreatitis. This pain is usually very intense and steady. Relief of pain by sitting up and bending forward is typical. Breathing may be shallow as deep breathing causes more pain (Carson-DeWitt 20020.

Other prominent symptoms are nausea and vomiting (emesis). There may be a slight fever and in severely ill patients there may be shock. The blood pressure may be high (when pain is prominent) or low (if internal bleeding or dehydration has occurred). Typically, both the heart and respiratory rates are elevated. Abdominal tenderness is usually found but may be less severe than expected given the patient's degree of abdominal pain. Bowel sounds may be reduced as a reflection of the reflex bowel paralysis (i.e. ileus) that may accompany any abdominal catastrophe.

Findings on the physical exam will vary according to the severity of the pancreatitis, and whether or not it is associated with significant internal bleeding.

Sometimes there are few symptoms with gradual impairment of function and the patient may not visit a doctor until the damage is extensive and permanent.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for pancreatitis are "two of the following three features: 1) abdominal pain characteristic of acute pancreatitis, 2) serum amylase and/or lipase greater than or equal to 3 times the upper limit of normal, and 3) characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on a CT scan" (Banks and Freeman 2006).

Amylase and lipase levels

An early diagnosis can be made by observing high levels of pancreatic enzymes in the blood (amylase and lipase). Often one, or both, are elevated in cases of pancreatitis (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

Two practice guidelines state:

It is usually not necessary to measure both serum amylase and lipase. Serum lipase may be preferable because it remains normal in some nonpancreatic conditions that increase serum amylase including macroamylasemia, parotitis, and some carcinomas. In general, serum lipase is thought to be more sensitive and specific than serum amylase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis" (Banks and Freeman 2006).

Although amylase is widely available and provides acceptable accuracy of diagnosis, where lipase is available it is preferred for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis (recommendation grade A)" (UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis 2005).

Most (Smith et al. 2005; Treacy et al. 2001; Steinberg et al. 1985; Wang et al. 1989; Keim et al. 1998) but not all (Ignjatović et al. 2000; Sternby et al. 1996) individual studies support the superiority of the lipase. In one large study, there were no patients with pancreatitis who had an elevated amylase with a normal lipase (Smith et al. 2005). Another study found that the amylase could add diagnostic value to the lipase, but only if the results of the two tests were combined with a discriminant function equation (Corsetti et al. 1993).

However, increased levels of amylase and lipase can also occur in other diseases and, further, those conditions may also cause pain that resembles that of pancreatitis, such as cholecystitis, perforated ulcer, bowel infarction (i.e. dead bowel as a result of poor blood supply), and even diabetic ketoacidosis. In addition, later in the progression of the disease, and in chronic pancreatitis, these enzyme levels are no longer elevated (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

Imaging

Although ultrasound imaging and CT scanning of the abdomen can be used to confirm the diagnosis of pancreatitis, neither is usually necessary as a primary diagnostic modality (Fleszler et al. 2003). In addition, CT contrast may exacerbate pancreatitis (McMenamin and Gates 1996), although this is disputed (Hwang et al. 2000).

Ultrasound imaging and x rays may reveal gallstones, a major causal factor, and the gastrointestinal tract will show signs of inactivity due to the presence of pancreatitis. Chest x rays may show abnormalities due to air trapping from shallow breathing or lung complications. CT scans may reveal the inflammation and fluid accumulation of pancreatitis. Calcification of the pancreas may be observed on x rays (Carson De-Witt 2002).

X rays, CT scanning, and ultrasonography may be complemented with an endoscopic inspection of the pancreas. All of these can identify both causes and complications of the disease (Smith 2008).

Treatment

The treatment of pancreatitis depends on the cause and the severity of the illness. In the case of alcohol abuse, or abuse of other drugs, the attack may be allowed to run its course while the patient abstains from the toxic agent. However, even mild attacks often require hospitalization for the sake of painkillers and intravenous hydration therapy (Smith 2008). Treatment often involves replacing lost flids, and treatment of pain with various medications (Carson-DeWitt 2002). Often the patient is not allowed to eat in order to decrease pancreatic function and discharge of harmful enzymes (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

General principles of treatment include:

- Provision of pain relief. In the past this was done preferentially with meperidine (Demerol), but it is now not thought to be superior to any narcotic analgesic. Indeed, given meperidine's generally poor analgesic characteristics and its high potential for toxicity, it should not be used for the treatment of the pain of pancreatitis. The preferred analgesic is morphine for acute pancreatitis.

- Provision of adequate replacement fluids and salts (intravenously).

- Limitation of oral intake (with dietary fat restriction the most important point). NG tube feeding is the preferred method to avoid pancreatic stimulation and possible infection complications caused by bowel flora.

- Monitoring and assessment for, and treatment of, the various complications listed below.

When necrotizing pancreatitis ensues and the patient shows signs of infection, it is imperative to start antibiotics such as Imipenem due to the high penetration of the drug in the pancreas. Floroquinolone plus metronidazole is another treatment option.

Surgery may be needed even in cases not related to gallstones, such as to block sympathetic nerves causing uncontrollable pain, or to remove part or all of the pancreas (Smith 2008). Oral medications and insulin injections may be needed in some cases (Carson DeWitt 2002).

Prognosis

There are several scoring systems used to help predict the severity of an attack of pancreatitis. The Apache II has the advantage of being available at the time of admission, as opposed to 48 hours later for the Glasgow criteria and Ranson criteria. However, the Glasgow criteria and Ranson criteria are easier to use.

Ranson criteria

The most commonly used system is the Ransom, which involves identification of 11 different signs (Ranson's signs), with the first five evaluated when the patient is admitted to the hospital and the last five signs reviewed 48 hours after admission to the hospital. Once it is determined how many of these are present and the patient is given a score, the doctor can predict the risk of death, with the more signs, the greater the chance of fatal complications (Carson-DeWitt 2002).

At admission:

- age in years > 55 years

- white blood cell count > 16000 /mcL

- blood glucose > 11 mmol/L (>200 mg/dL)

- serum AST > 250 IU/L

- serum LDH > 350 IU/L

After 48 hours:

- Haematocrit fall > 11.3444 percent

- increase in BUN by 1.8 or more mmol/L (5 or more mg/dL) after IV fluid hydration

- hypocalcemia (serum calcium < 2.0 mmol/L (<8.0 mg/dL))

- hypoxemia (PO2 < 60 mmHg)

- Base deficit > 4 Meq/L

- Estimated fluid sequestration > 6 L

The criteria for point assignment is that a certain breakpoint be met at anytime during that 48 hour period, so that in some situations it can be calculated shortly after admission. It is applicable to both biliary and alcoholic pancreatitis.

Interpretation

- If the score ≥ 3, severe pancreatitis likely.

- If the score < 3, severe pancreatitis is unlikely

Or

- Score 0 to 2: 2 percent mortality

- Score 3 to 4: 15 percent mortality

- Score 5 to 6: 40 percent mortality

- Score 7 to 8: 100 percent mortality

Glasgow criteria

Glasgow's criteria (Corfield et al. 1985): The original system used 9 data elements. This was subsequently modified to 8 data elements, with removal of assessment for transaminase levels (either AST (SGOT) or ALT (SGPT) greater than 100 U/L).

On Admission

- Age >55 yrs

- WBC Count >15 x109/L

- Blood Glucose >10 mmol/L (No Diabetic History)

- Serum Urea >16 mmol/L ( No response to IV fluids)

- Arterial Oxygen Saturation <60 mmHg

Within 48 hours

- Serum Calcium <2 mmol/L

- Serum Albumin <32 g/L

- LDH >600 units/L

- AST/ALT >200 units/L

Complications

Acute (early) complications of pancreatitis include

- shock,

- hypocalcemia (low blood calcium),

- high blood glucose,

- dehydration, and kidney failure (resulting from inadequate blood volume which, in turn, may result from a combination of fluid loss from vomiting, internal bleeding, or oozing of fluid from the circulation into the abdominal cavity in response to the pancreas inflammation, a phenomenon known as Third Spacing).

- Respiratory complications are frequent and are major contributors to the mortality of pancreatitis. Some degree of pleural effusion is almost ubiquitous in pancreatitis. Some or all of the lungs may collapse (atelectasis) as a result of the shallow breathing, which occurs because of the abdominal pain. Pneumonitis may occur as a result of pancreatic enzymes directly damaging the lung, or simply as a final common pathway response to any major insult to the body (i.e. ARDS or Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome).

- Likewise, SIRS (Systemic inflammatory response syndrome) may ensue.

- Infection of the inflamed pancreatic bed can occur at any time during the course of the disease. In fact, in cases of severe hemorrhagic pancreatitis, antibiotics should be given prophylactically.

Late complications

Late complications include recurrent pancreatitis and the development of pancreatic pseudocysts. A pancreatic pseudocyst is essentially a collection of pancreatic secretions that has been walled off by scar and inflammatory tissue. Pseudocysts may cause pain, may become infected, may rupture and hemorrhage, may press on and block structures such as the bile duct, thereby leading to jaundice, and may even migrate around the abdomen.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Banks, P., and M. Freeman. 2006. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 101(10): 2379–2400. PMID 17032204. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Carson-DeWitt, R. 2002. Pancreatitis. Pages 2477-2481 in J. Longe, and D. S. Blanchfield, Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, Volume 4, 2nd ed. Detroit, MI: Gale Group. ISBN 0787654892 (set). ISBN 0787654930 (volume).

- Corfield, A. P., M. J. Cooper, R. C. Williamson, et al. 1985. Prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis: Prospective comparison of three prognostic indices. Lancet 2(8452): 403–407. PMID 2863441. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Corsetti, J., C. Cox, T. Schulz, and D. Arvan. 1993. Combined serum amylase and lipase determinations for diagnosis of suspected acute pancreatitis. Clin Chem 39(12): 2495–2499. PMID 7504593. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Fleszler, F., F. Friedenberg, B. Krevsky, D. Friedel, and L. Braitman. 2003. Abdominal computed tomography prolongs length of stay and is frequently unnecessary in the evaluation of acute pancreatitis. Am J Med Sci 325(5): 251–255. PMID 12792243. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Hwang, T., K. Chang, and Y. Ho. 2000. Contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography does not aggravate the clinical severity of patients with severe acute pancreatitis: Reevaluation of the effect of intravenous contrast medium on the severity of acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg 135(3): 287–290. PMID 10722029. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Ignjatović, S., N. Majkić-Singh, M. Mitrović, and M. Gvozdenović. 2000. Biochemical evaluation of patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 38(11): 1141–1144. PMID 11156345. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Keim, V., N. Teich, F. Fiedler, W. Hartig, G. Thiele, and J. Mössner. 1998. A comparison of lipase and amylase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in patients with abdominal pain. Pancreas 16(1): 45–49. PMID 9436862. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Lin, X. Z., S. S. Wang, Y. T. Tsai, et al. 1989. Serum amylase, isoamylase, and lipase in the acute abdomen. Their diagnostic value for acute pancreatitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 11(1): 47–52. PMID 2466075. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- McMenamin, D., and L. Gates. 1996. A retrospective analysis of the effect of contrast-enhanced CT on the outcome of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 91(7): 1384–1387. PMID 8678000. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Smith, R. 2008. Pancreatitis. Pages 2060-2062 in A. Chang, et al., Magill's Medical Guide, Volume IV, Neuralgia, neuritis, and neuropahty—Smallpox, 4th revised ed. Pasadena, CA: Salem Press. ISBN 9781587653841 (set). ISBN 9781587653889 (volume).

- Smith, R. C., J. Southwell-Keely, and D. Chesher. 2005. Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis? ANZ J Surg 75(6): 399–404. PMID 15943725. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Steinberg, W. M., S. S. Goldstein, N. D. Davis, J. Shamma'a, and K. Anderson. 1985. Diagnostic assays in acute pancreatitis. A study of sensitivity and specificity. Ann. Intern. Med. 102(5): 576–580. PMID 2580467. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Sternby, B., J. F. O'Brien, A. R. Zinsmeister, and E. P. DiMagno. 1996. What is the best biochemical test to diagnose acute pancreatitis? A prospective clinical study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 71(12): 1138–1144. PMID 8945483. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Treacy, J., A. Williams, R. Bais, et al. 2001. Evaluation of amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. ANZ J Surg 71(10): 577–582. PMID 11552931. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. 2005. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 54(Suppl 3): iii1-iii9. PMID 15831893. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.