| Iroquois Haudenosaunee | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | ||||||

| approx. 125,000 (30,000 to 80,000 in the U.S. 45,000 in Canada) | ||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||

| ||||||

| Languages | ||||||

| Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, Tuscarora, English, French | ||||||

| Religions | ||||||

| Christianity, Longhouse religion |

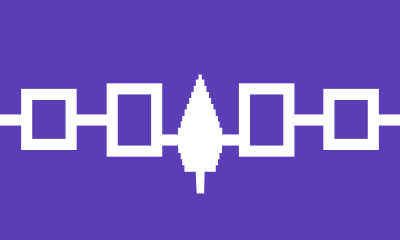

The Iroquois Nation or Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) was a powerful and unique gathering of Native American tribes that lived prior to the arrival of Europeans in the area around New York State. In many ways, the constitution that bound them together, The Great Binding Law, was a precursor to the American Constitution. It was received by the spiritual leader, Deganawida (The Great Peacemaker), assisted by the Mohawk leader, Hiawatha five tribes came together. These were the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca. Later, the Tuscarora joined and this group of six tribes united together under one law and a common council.

For many years the Iroquois maintained their autonomy, battling the French who were allied with the Huron, enemy of the Iroquois. Generally siding with the British, a schism developed during the American Revolutionary War when the Oneida and Tuscarora supported the Americans. After the American victory, Joseph Brant and a group of Iroquois left and settled in Canada on land given them by the British. Many of the Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, and Tuscarora stayed in New York, settling on reservations where they continue to live, and many Oneida moved to a reservation in Wisconsin. Although separated geographically, the Iroquois culture and traditions are preserved in these locations.

Introduction

The word Iroquois, the most common name for the confederacy, has two potential origins. First, the Haudenosaunee often ended their oratory with the phrase "hiro kone"; "hiro" which translates as "I have spoken," "kone" which can be translated several ways, the most common being "in joy," "in sorrow," or "in truth."[1]"Hiro kone" to the French encountering the Haudenosaunee would sound like "Iroquois," pronounced iʁokwa in French. An alternate possible origin of the name Iroquois is reputed to come from a French version of a Huron (Wyandot) name—considered an insult—meaning "Black Snakes." The Iroquois were enemies of the Huron and the Algonquin, who were allied with the French, due to their rivalry in the fur trade.

The Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the "League of Peace and Power"; the "Five Nations"; the "Six Nations"; or the "People of the Long house") is a group of First Nations/Native Americans that originally consisted of five tribes: the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Onondaga, the Cayuga, and the Seneca. A sixth tribe, the Tuscarora, joined after the original five nations were formed. The original five tribes united between 1450 and 1600 by two spiritual leaders, Hiawatha and Deganawida who sought to unite the tribes under a doctrine of peace. The Iroquois sided with the British during the American Revolution.

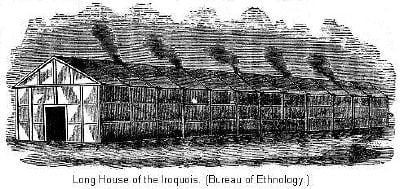

The combined leadership of the Nations is known as the Haudenosaunee. It should be noted that "Haudenosaunee" is the term that the people use to refer to themselves. Haudenosaunee means "People of the Long House." The term is said to have been introduced by The Great Peacemaker at the time of the formation of the Confederacy. It implies that the Nations of the confederacy should live together as families in the same long house. Symbolically, the Seneca were the guardians of the western door of the "tribal long house," and the Mohawk were the guardians of the eastern door.

At the time that Europeans first arrived in North America, the Confederacy was based in what is now the northeastern United States and southern Canada, including New England, Upstate New York, and Pennsylvania, Ontario, and Quebec. After the American Revolutionary War most of the Iroquois moved to Canada where they were given land by the British.

The Iroquois nations' political union and democratic government has been credited by some] as one of the influences on the United States Constitution.[3] However, that theory has fallen into disfavor among many historians, and is regarded by others as mythology:

The voluminous records we have for the constitutional debates of the late 1780s contain no significant references to the Iroquois.[4]

History

Early History

The Iroquois Confederacy was established prior to major European contact, complete with a constitution known as the Gayanashagowa (or "Great Law of Peace") with the help of a memory device in the form of special beads called wampum that have inherent spiritual value (wampum has been inaccurately compared to money in other cultures). Most anthropologists have traditionally speculated that this constitution was created between the middle 1400s and early 1600s. However, recent archaeological studies have suggested the accuracy of the account found in oral tradition, which argues that the federation was formed around August 31, 1142 based on a coinciding solar eclipse.[5]

The two spiritual leaders, Ayonwentah (generally called Hiawatha due to the Longfellow poem) and "Deganawidah, The Great Peacemaker," brought a message of peace to squabbling tribes. The tribes who joined the League were the Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga and Mohawks. Once they ceased most infighting, they rapidly became one of the strongest forces in seventeenth and eighteenth century northeastern North America.

According to legend, an evil Onondaga chieftain named Tadadaho was the last to be converted to the ways of peace by The Great Peacemaker and Ayonwentah, and became the spiritual leader of the Haudenosaunee. This event is said to have occurred at Onondaga Lake near Syracuse, New York. The title Tadadaho is still used for the league's spiritual leader, the fiftieth chief, who sits with the Onondaga in council, but is the only one of the fifty chosen by the entire Haudenosaunee people.

The League engaged in a series of wars against the French and their Iroquoian-speaking Wyandot ("Huron") allies. They also put great pressure on the Algonquian peoples of the Atlantic coast and what is now boreal Canadian Shield region of Canada and not infrequently fought the English colonies as well. During the seventeenth century, they are also credited with having conquered and/or absorbed the Neutral Indians and Erie Tribe to the west as a way of controlling the fur trade, even though other reasons are often given for these wars.

By 1677, the Iroquois formed an alliance with the English through an agreement known as the Covenant Chain. Together, they battled the French, who were allied with the Huron, another Iroquoian people but a historic foe of the Confederacy.

The Iroquois were at the height of their power in the seventeenth century, with a population of about twelve thousand people. League traditions allowed for the dead to be symbolically replaced through the "Mourning War," raids intended to seize captives to replace lost compatriots and take vengeance on non-members. This tradition was common to native people of the northeast and was quite different from European settlers' notions of combat.

Four delegates of the Iroquoian Confederacy, the "Indian Kings," traveled to London, England, in 1710 to meet Queen Anne in an effort to cement an alliance with the British. Queen Anne was so impressed by her visitors that she commissioned their portraits by court painter John Verelst. The portraits are believed to be some of the earliest surviving oil portraits of Native American peoples taken from life.[6]

Principles of the Peace Constitution

Originally the principal object of the council was to raise up sachems, or chiefs, to fill vacancies in the ranks of the ruling body occasioned by death or deposition; but it transacted all other business which concerned the common welfare. Eventually the council fell into three kinds of ceremonies, which may be distinguished as Civil, Mourning, and Religious.

The first declared war and made peace, sent and received embassies, entered into treaties with foreign tribes, regulated the affairs of subjugated tribes, as well as other general welfare issues. The second raised up sachems and invested them with office, termed the Mourning Council (Henundonuhseh) because the first of its ceremonies was the lament for the deceased ruler whose vacant place was to be filled. The third was held for the observance of a general religious festival, as an occasion for the confederated tribes to united under the auspices of a general council in the observance of common religious rites. But as the Mourning Council was attended with many of the same ceremonies it came, in time, to answer for both. It became the only council they held when the civil powers of the confederacy terminated with the supremacy over them of the state.

Member nations

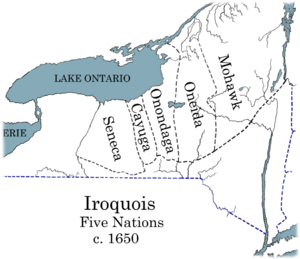

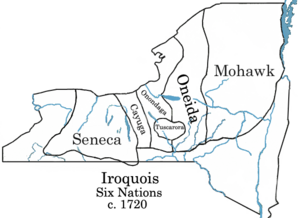

The first five nations listed below formed the original Five Nations (listed from west to north); the Tuscarora became the sixth nation in 1720, when they fled north from the British colonization of North Carolina and petitioned to become the Sixth Nation. This is a non-voting position, but places them under the protection of the Confederacy.

| English | Iroquoian | Meaning | 17th/18th century location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seneca | Onondowahgah | "People of the Great Hill" | Seneca Lake and Genesee River |

| Cayuga | Guyohkohnyoh | "People of the Great Swamp" | Cayuga Lake |

| Onondaga | Onundagaono | "People of the Hills" | Onondaga Lake |

| Oneida | Onayotekaono | "People of Upright Stone" | Oneida Lake |

| Mohawk | Kanien'kéhaka | "People of the Flint" | Mohawk River |

| Tuscarora1 | Ska-Ruh-Reh | "Shirt-Wearing People" | From North Carolina2 |

1 Not one of the original Five Nations; joined 1720.

2 Settled between Oneidas and Onondagas.

|

|

Eighteenth century

During the French and Indian War, the Iroquois sided with the British against the French and their Algonquin allies, both traditional enemies of the Iroquois. The Iroquois hoped that aiding the British would also bring favors after the war. Practically, few Iroquois joined the fighting and the Battle of Lake George found a group of Mohawk and French ambush a Mohawk-led British column. The British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 after the war, which restricted white settlement beyond the Appalachians, but this was largely ignored by the settlers and local governments.

During the American Revolution, many Tuscarora and the Oneida sided with the Americans, while the Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, and Cayuga remained loyal to Great Britain. This marked the first major split among the Six Nations. After a series of successful operations against frontier settlements, led by the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant and his British allies, the United States reacted with vengeance. In 1779, George Washington ordered Col. Daniel Brodhead and General John Sullivan to lead expeditions against the Iroquois nations to "not merely overrun, but destroy," the British-Indian alliance. The campaign successfully ended the ability of the British and Iroquois to mount any further significant attacks on American settlements.

In 1794, the Confederacy entered into the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States. After the American Revolutionary War, Captain Joseph Brant and a group of Iroquois left New York to settle in Canada. As a reward for their loyalty to the English Crown, they were given a large land grant on the Grand River. Brant's crossing of the river gave the original name to the area: Brant's Ford. By 1847, European settlers began to settle nearby and named the village Brantford, Ontario. The original Mohawk settlement was on the south edge of the present day city at a location favorable for landing canoes. Prior to this land grant, Iroquois settlements did exist in that same area and elsewhere in southern Ontario, extending further north and east (from Lake Ontario eastwards into Quebec around present-day Montreal). Extensive fighting with Huron meant the continuous shifting of territory in southern Ontario between the two groups long before European influences were present.

Culture

Government

The Iroquois have a representative government known as the Grand Council. Each tribe sends chiefs to act as representatives and make decisions for the whole nation. The number of chiefs has never changed.

- 14 Onondaga

- 10 Cayuga

- 9 Oneida

- 9 Mohawk

- 8 Seneca

- 0 Tuscarora

Haudenosaunee clans

Within each of the six nations, people are divided into a number of matrilineal clans. Each clan is distinguished by its association with a different animal. Men wore feathered hats, called gustoweh, of the style of his mother's tribe. A gustoweh consists of a dome formed from wood used for making baskets, often ash, and covered with turkey feathers. Sockets are constructed to hold upright and side (laying down) eagle feathers, with each tribe having a different number and arrangement of these feathers. Thus, Mohawk three upright feathers; Oneida have two upright feathers and the third for a side feather; the Onondaga have two upright feathers; the Cayuga gustoweh has one feather at a forty-five degree angle; Seneca have one upright feather; and the Tuscarora have no eagle feathers on top.[7]

The number of clans varies by nation, currently from three to eight, with a total of nine different clan names.

| Seneca | Cayuga | Onondaga | Tuscarora | Oneida | Mohawk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolf | Wolf | Wolf | Wolf | Wolf | Wolf |

| Bear | Bear | Bear | Bear | Bear | Bear |

| Turtle | Turtle | Turtle | Turtle | Turtle | Turtle |

| Snipe | Snipe | Snipe | Snipe | — | Snipe |

| Deer | — | Deer | Deer | — | — |

| Beaver | — | Beaver | Beaver | — | — |

| Heron | Heron | Heron | — | — | — |

| Hawk | — | Hawk | — | — | — |

| — | — | Eel | Eel | — | — |

Economy

The economy of the Iroquois originally focused on communal production and combined elements of both horticulture and hunter-gatherer systems. The Iroquois people were predominantly agricultural, harvesting the "Three Sisters" commonly grown by Native American groups: maize, beans, and squash. They developed certain cultural customs related to their lifestyle. Among these developments were ideas concerning the nature and management of property.

The Iroquois developed a system of economics very different from the now dominant Western variety. This system was characterized by such components as communal land ownership, division of labor by gender, and trade mostly based on gift economics.

The structure of the traditional Iroquois economy created a unique property and work ethic. The threat of theft was almost nonexistent, since little was held by the individual except basic tools and implements that were so prevalent they had little value. The only goods worth stealing would have been wampum. A theft-free society can be respected by all, communal systems such as that of the Iroquois are often criticized for not providing any incentive to work. In order for the Iroquois to succeed without an individual incentive, they had to develop a communal work ethic. Virtue became synonymous with productivity. The idealized Iroquois man was a good warrior and productive hunter while the perfect woman excelled in agriculture and housekeeping.[8] By emphasizing an individual's usefulness to society, the Iroquois created a mindset that encouraged their members to contribute even though they received similar benefits no matter how hard they worked.

As a result of their communal system, some would expect the Iroquois to have a culture of dependence without individuality. The Iroquois, however, had a strong tradition of autonomous responsibility. Iroquois men were taught to be self-disciplined, self-reliant, and responsible as well as stoic.[9] The Iroquois attempted to eliminate any feelings of dependency during childhood and foster a desire for responsibility. At the same time, the child would have to participate in a communal culture, so children were taught to think as individuals but work for the community.[9]

Contact with Europeans in the early 1600s had a profound impact on the economy of the Iroquois. At first, they became important trading partners, but the expansion of European settlement upset the balance of the Iroquois economy. By 1800 the Iroquois had been confined to reservations, and they had to adapt their traditional economic system. In the twentieth century, some of the Iroquois groups took advantage of their independent status on the reservation and started Indian casinos. Other Iroquois have incorporated themselves directly into the outside economies off the reservation.

Land ownership

The Iroquois had an essentially communal system of land distribution. The tribe owned all lands but gave out tracts to the different clans for further distribution among households for cultivation. The land would be redistributed among the households every few years, and a clan could request a redistribution of tracts when the Clan Mothers' Council gathered.[8] Those clans that abused their allocated land or otherwise did not take care of it would be warned and eventually punished by the Clan Mothers' Council by having the land redistributed to another clan.[10] Land property was really only the concern of the women, since it was the women's job to cultivate food and not the men's.[8]

The Clan Mothers' Council also reserved certain areas of land to be worked by the women of all the different clans. Food from such lands, called kěndiǔ"gwǎ'ge' hodi'yěn'tho, would be used at festivals and large council gatherings.[10]

Division of labor: agriculture and forestry

The division of labor reflected the dualistic split common in the Iroquois culture. The twin gods Sapling (East) and Flint (West) embodied the dualistic notion of two complementary halves. Dualism was applied to labor with each gender taking a clearly defined role that complemented the work of the other. Women did all work involving the field while men did all work involving the forest including the manufacture of anything involving wood. The Iroquois men were responsible for hunting, trading, and fighting, while the women took care of farming, food gathering, and housekeeping. This gendered division of labor was the predominate means of dividing work in Iroquois society.[11] At the time of contact with Europeans, Iroquois women produced about 65 percent of the food and the men 35 percent. The combined production of food was successful to the point where famine and hunger were extremely rare—early Europeans settlers often envied the success of Iroquois food production.

The Iroquois system of work matched their system of land ownership. Since the Iroquois owned property together, they worked together as well. The women performed difficult work in large groups, going from field to field helping one another work each others' land. Together they would sow the fields as a "mistress of the field" distributed a set amount of seeds to each of the women.[11] The Iroquois women of each agricultural group would select an old but active member of their group to act as their leader for that year and agree to follow her directions. The women performed other work cooperatively as well. The women would cut their own wood, but their leader would oversee the collective carrying of the wood back to the village.[8] The women's clans performed other work, and according to Mary Jemison, a white girl kidnapped and assimilated into their culture, the collective effort averted "every jealousy of one having done more or less work than another."

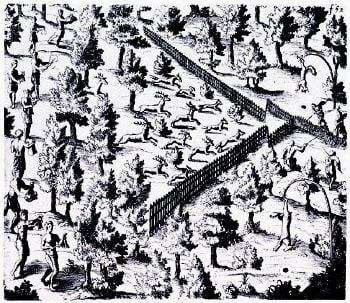

The Iroquois men also organized themselves in a cooperative fashion. Of course, the men acted collectively during military actions, as there is little sense in a single individual fighting entirely alone in battle. The other jobs of men, such as hunting and fishing, also involved cooperative elements similar to women's cooperation. However, the men differed from the women in that they more often organized as a whole village rather than as a clan. The men organized hunting parties where they used extensive cooperation to kill a large amount of game. One first hand account told of a large hunting party that built a large brush fence in a forest forming a V. The hunters burned the forest from the open side of the V, forcing the animals to run towards the point where the village's hunters waited in an opening. A hundred deer could be killed at a time under such a plan.

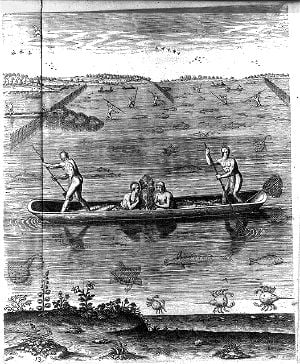

The men also fished in large groups. Extensive fishing expeditions often took place where men in canoes with weirs and nets covered entire streams to reap large amounts of fish, sometimes a thousand in half of a day.[8] A hunting or fishing party's takings were considered common property and would be divided among the party by the leader or taken to the village for a feast. Hunting and fishing were not always cooperative efforts, but the Iroquois generally did better in parties than as individuals.

Trade

The cooperative production and communal distribution of goods made internal trade within the Iroquois Confederacy pointless, but external trade with tribes in regions with resources the Iroquois lacked served a purpose. The Iroquois traded excess corn and tobacco for the pelts from the tribes to the north and the wampum from the tribes to the east. The Iroquois used gift exchange more often than any other mode of exchange. This gift-giving reflected the reciprocity in Iroquois society. The exchange would begin with one clan giving another tribe or clan a present with the expectation of some sort of needed commodity being given in return. This form of trade ties to the Iroquois culture's tendency to share property and cooperate in labor. In all cases no explicit agreement is made, but one service is performed for the community or another member of the community's good with the expectation that the community or another individual would give back.[8] External trade offered one of the few opportunities for individual enterprise in Iroquois society. A person who discovered a new trading route had the exclusive right to trade along the same route in the future; however, clans would still collectivize trading routes to gain a monopoly on a certain type of trade.

The arrival of Europeans created the opportunity for greatly expanded trade. Furs were in demand in Europe, and they could be acquired cheaply from Indians in exchange for manufactured goods the Indians could not make themselves. Trade did not always benefit the Indians. The British took advantage of the gift-giving culture. They showered the Iroquois with European goods, making them dependent on such items as rifles and metal axes. The Iroquois had little choice but to trade for gunpowder after they had discarded their other weapons. The British primarily used these gifts to gain support among the Iroquois for fighting against the French.[3]

The Iroquois also traded for alcohol, a substance they did not have before the arrival of Europeans. Eventually, this would have a very negative impact on Iroquois society. The problem became so bad by 1753 that Scarrooyady, an Iroquois Chief, had to petition the Governor of Pennsylvania to intervene in trade:

Your Traders now bring scarce anything but Rum and Flour; they bring little powder and lead, or other valuable goods … and get all the skins that should go to pay the debts we have contracted for goods bought of the Fair Traders; by this means we not only ruin ourselves but them too. These wicked Whiskey Sellers, when they have once got the Indians in liquor, make them sell their very clothes from their backs. In short, if this practice be continued, we must be inevitably ruined.[12]

Land after the Europeans arrived

The Iroquois system of land management had to change with the coming of the Europeans and the forced isolation to reservations. The Iroquois had a system of collectively owned land free to be used as needed by their members. While this system was not wholly collective as land was distributed to individual family groups, the Iroquois lacked the Western conception of property as a commodity. After the Europeans arrived and placed the Iroquois on reservations, the natives had to adjust their property system to a more Western model. Despite the influence of Western culture, the Iroquois have maintained a unique view of property over the years. Modern-day Iroquois Doug George-Kanentiio sums up his perception of the Iroquois property view: The Iroquois have

no absolute right to claim territory for purely monetary purposes. Our Creator gave us our aboriginal lands in trust with very specific rules regarding its uses. We are caretakers of our Mother Earth, not lords of the land. Our claims are valid only so far as we dwell in peace and harmony upon her.[13]

Similar sentiments were expressed in a statement by the Iroquois Council of Chiefs (or Haudenosaunee) in 1981. The Council distinguished the "Western European concepts of land ownership" from the Iroquois view that "the earth is sacred" and "was created for all to use forever—not to be exploited merely for this present generation." Land is not just a commodity and "In no event is land for sale." The statement goes on, "Under Haudenosaunee law, Gayanerkowa, the land is held by the women of each clan." It is principally the women who are responsible for the land, who farm it, and who care for it for the future generations. When the Confederacy was formed, the separate nations formed one union. The territory of each nation became Confederacy land even though each nation continued to have a special interest in its historic territory the Council's statement reflects the persistence of a unique view of property among the Iroquois.

The system of the Grand River Iroquois (two Iroquois reservations in Canada) integrated the traditional Iroquois property structure with the new way of life after being confined to a reservation. The reservation was established under two deeds in the eighteenth century. These deeds gave corporate ownership of the reservation lands to the Six Nations of the Iroquois. Individuals would then take a perpetual lease on a piece of land from the Confederacy. The Iroquois idea that land came into one's possession if cared for and reverted to public control if left alone persisted in reservation property law. In one property dispute case, the Iroquois Council sided with the claimant who had made improvements and cultivated the land over the one who had left it alone. The natural resources on the land belonged to the tribe as a whole and not to those who possessed the particular parcel. The Iroquois leased the right to extract stone from the lands in one instance and fixed royalties on all the production. After natural gas had been discovered on the reservation, the Six Nations took direct ownership of the natural gas wells and paid those who had wells on their land compensation only for damages done by gas extraction. This setup closely resembled the precontact land distribution system where the tribes actually owned the land and distributed it for use but not unconditional ownership. Another instance of traditional Iroquois property views impacting modern-day Indian life involves the purchase of land in New York State by the Seneca-Cayuga tribe, perhaps for a casino. The casino would be an additional collectively-owned revenue maker. The Seneca-Cayuga already own a bingo hall, a gas station, and a cigarette factory. The later-day organization of reservation property directly reflects the influence of the precontact view of land ownership.

Iroquois mythology

The Iroquois believed in a supreme spirit, Orenda, the "Great Spirit" from whom all other spirits were derived. Atahensic (also called Ataensic) is a sky goddess who fell to the earth at the time of creation. According to legend, she was carried down to the land by the wings of birds. After her fall from the sky she gave birth to Hahgwehdiyu and Hahgwehdaetgah, twin sons. She died in childbirth and was considered the goddess of pregnancy, fertility, and feminine skills.

Hahgwehdiyu put a plant into his mothers lifeless body and from it grew maize as a gift to humankind. Hahgwehdaetgah his twin was an evil spirit.

Gaol is the wind god. Gohone is the personification of the winter. Adekagagwaa is the personification of the summer. Onatha is a fertility god and patron of farmers, particularly farmers of wheat. Yosheka is another creator god. A giant named Tarhuhyiawahku held the sky up.

The Oki is the personification of the life-force of the Iroquois, as well as the name of the life force itself. It is comparable to Wakanda (Lakota) and the Manitou (Algonquian).

The Jogah are nature spirits, similar to both nymphs and fairies. Ha Wen Neyu is the "Great Spirit."

The first people were created by Iosheka, a beneficient God who heals disease, defeated demons, and gave many of the Iroquois magical and ceremonial rituals, as well as tobacco, a central part of the Iroquois religion. He is also venerated in Huron mythology.

The north wind is personified by a bear spirit named Ya-o-gah, who lived in a cave and was controlled by Gah-oh. Ya-o-gah could destroy the world with his fiercely cold breath, but is kept in check by Gah-oh.

Sosondowah was a great hunter (known for stalking a supernatural elk) who was captured by Dawn, a goddess who needed him as a watchman. He fell in love with Gendenwitha ("she who brings the day"; alt: Gendewitha), a human woman. He tried to woo her with song. In spring, he sang as a bluebird, in summer as a blackbird and in autumn as a hawk, who then tried to take Gendenwitha with him to the sky. Dawn tied him to her doorpost. She then changed Gendenwitha into the Morning Star, so he could watch her all night but never be with her.

Contemporary Life

The total number of Iroquois today is hard to establish. About 45,000 Iroquois lived in Canada in 1995. In the 2000 census, 80,822 people in the United States claimed Iroquois ethnicity, with 45,217 of them claiming only Iroquois background. However, tribal registrations in the United States in 1995 numbered about 30,000 in total.

Many Iroquois have been fully integrated into the surrounding Western economy of the United States and Canada. For others their economic involvement is more isolated in the reservation. Whether directly involved in the outside economy or not, most of the Iroquois economy is now greatly influenced by national and world economies. The Iroquois have been involved in the steel construction industry for over a hundred years, with many men from the Mohawk nations working on such high-steel projects as the Empire State Building and World Trade Center.[14]

Inside the reservation the economic situation has often been bleak. Many reservations have successful businesses, however, and the nations function today as sovereign, independent nations, living on a portion of their ancestral territory and maintaining their own distinct laws, language, customs, and culture.[15] The Seneca reservation contains the City of Salamanca, New York, a center of the hardwoods industry. The Seneca make use of their independent reservation status to sell gasoline and cigarettes tax-free and run high-stakes bingo operations. The Seneca have also opened casinos in New York State, including Niagara Falls and in Salamanca, New York.

The Oneida have also set up casinos on their reservations in New York and Wisconsin, and are one of the largest employers in northeastern Wisconsin. The Oneida business ventures have brought millions of dollars into the community and improved the standard of living.[16]

Notes

- ↑ The Iroquois Confederacy Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ↑ Hiawatha Belt Onondaga Nation. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bruce E. Johansen, Forgotten Founders: How the American Indian Helped Shape Democracy (Boston, MA: Harvard Common Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0916782900).

- ↑ Jack Rakove, Did the Founding Fathers Really Get Many of Their Ideas of Liberty from the Iroquois? History News Network, July 21, 2005. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ↑ Barbara A. Mann and Jerry L. Fields, "A Sign in the Sky: Dating the League of the Haudenosaunee," American Indian Culture and Research Journal 21(2) (1997):105-163.

- ↑ Four Kings National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ↑ Traditional Iroquoian Headdress The Wampum Shop. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Sara H. Stites, Economics of the Iroquois (Sagwan Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1298913326).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 A. Wallace, The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1992, ISBN 039471699X).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bruce E. Johansen (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Native American Economic History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 0313306230).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 J. Axtell (ed.), The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes (New York, NY: Oxford University Press 1981, ISBN 019502740X).

- ↑ Fur Trader Portland State University. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ↑ D. George-Kanentiio, Iroquois Culture and Commentary (Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1574160532).

- ↑ Walking High Steel: Mohawk Ironworkers at the World Trade Towers The Kitchen Sisters. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ↑ Today Onondaga Nation. Retrieved December, 2021.

- ↑ Jeff Lindsay, The Oneida Indians of Wisconsin Retrieved December 9, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Axtell, J. (ed). The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1981. ISBN 019502740X

- George-Kanentio, D. Iroquois Culture and Commentary. Santa Fe: NM:Clear Light Publishers, 2000. ISBN 1574160532

- Johansen, Bruce E. Forgotten Founders: How the American Indian Helped Shape Democracy. Boston, MA: Harvard Common Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0916782900

- Johansen, Bruce E. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Native American Economic History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999. ISBN 0313306230

- Seaver, James E. A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992. ISBN 0806123818

- Stites, Sara H. Economics of the Iroquois. Sagwan Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1298913326

- Wallace, A. The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca. New York, NY:Vintage Books, 1992. ISBN 039471699x

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 9780816062744

- Williams, Glenn F. Year of the Hangman: George Washington's Campaign Against the Iroquois. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1594160414

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.