Difference between revisions of "Benedict of Nursia" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

*Defining four kinds of monks: 1) [[Cenobite]]s, those "in a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot"; 2) [[Anchorite]]s, or [[hermit]]s, who, after long successful training in a monastery live a solitary existence, 3) "Sarabaites," living by twos and threes together with no rule or superior, and thus a law unto themselves; and 4) "Gyrovagues," wandering from one monastery to another, often slaves to their own wills and appetites. It is for the first of these kinds of monks, the cenobites, as that the Rule is written (chapter 1). | *Defining four kinds of monks: 1) [[Cenobite]]s, those "in a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot"; 2) [[Anchorite]]s, or [[hermit]]s, who, after long successful training in a monastery live a solitary existence, 3) "Sarabaites," living by twos and threes together with no rule or superior, and thus a law unto themselves; and 4) "Gyrovagues," wandering from one monastery to another, often slaves to their own wills and appetites. It is for the first of these kinds of monks, the cenobites, as that the Rule is written (chapter 1). | ||

| − | Benedict describes the necessary qualifications of an abbot and forbids him to make distinctions between persons in the monastery except on the basis of merit ( | + | Benedict describes the necessary qualifications of an abbot and forbids him to make distinctions between persons in the monastery except on the basis of merit (2). He ordains that members of the community shall be called council regarding matters of importance ( 3). |

He lists 73 "tools of the spiritual craft," constituing the duties of every Christian (chapter 4) and demands prompt, ungrudging, and absolute obedience to the superior in all his lawful commands (5). While stopping short of ordaining a rule of silence, he advises moderation in the use of speech (6) | He lists 73 "tools of the spiritual craft," constituing the duties of every Christian (chapter 4) and demands prompt, ungrudging, and absolute obedience to the superior in all his lawful commands (5). While stopping short of ordaining a rule of silence, he advises moderation in the use of speech (6) | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

A dean is to be appointed over every ten monks (21). Each monk is to have a separate bed and is to sleep in his habit; a light shall burn in the dormitory throughout the night (22). | A dean is to be appointed over every ten monks (21). Each monk is to have a separate bed and is to sleep in his habit; a light shall burn in the dormitory throughout the night (22). | ||

| − | Benedict specifies a graduated scale of punishments for various sins: private admonition, public reproof, separation from the community at meals and other group meetings, corporal punishment, and/or finally [[excommunication]] (23- | + | Benedict specifies a graduated scale of punishments for various sins: private admonition, public reproof, separation from the community at meals and other group meetings, corporal punishment, and/or finally [[excommunication]] (23-30). |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Officials are to be appointed to oversee the material goods of the monastery, and no private possessions are allowed without the permission of the abbot. Monks are to take turns serving in the kitchen. Children, as well as the sick and the elderly are to have certain dispensations from the strict Rule (31-37). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Scriptural and other readings are to be done aloud during meals, during which time verbal silence is to be observed by all except the reader. Hours for the meals are prescribe—two meals a day—with two cooked dishes at each. In addition, each monk is allowed a pound of bread and a half a pint of wine per day. Meat is prohibited except for the sick and the weak (38-41) | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | An edifying book is to be read in the evening, and there is to be strict silence after Compline (the day's final communal gathering). Penalties are prescribe for minor faults such as coming late to prayer or meals. The abbot is to appoint chanters and readers (42-47). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* Chapter 48 emphasizes the importance of daily manual labour appropriate to the ability of the monk. The hours of labor vary with the season but are never less than five hours a day. | * Chapter 48 emphasizes the importance of daily manual labour appropriate to the ability of the monk. The hours of labor vary with the season but are never less than five hours a day. | ||

* Chapter 49 recommends some voluntary self-denial for Lent, with the abbot's sanction. | * Chapter 49 recommends some voluntary self-denial for Lent, with the abbot's sanction. | ||

Revision as of 23:39, 22 January 2009

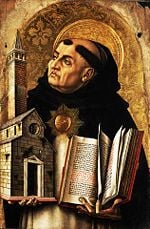

| Saint Benedict | |

|---|---|

Detail from fresco by Fra Angelico | |

| Abbot Patron of Europe | |

| Born | c. 480 in Norcia (Umbria, Italy) |

| Died | c. 547 in Monte Cassino |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Anglican Communion Eastern Orthodox Church Lutheran Church |

| Canonized | 1220 |

| Major shrine | Monte Cassino Abbey;

Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, near Orléans, France; Sacro Speco, at Subiaco, Italy |

| Feast | Western Christianity: 11 July (in pre-1969 calendars, 21 March) Byzantine Rite: 14 March |

| Attributes | -Bell, broken cup with serpent representing poison, bush, crosier, Benedictine cowl, copy of his Rule, rod of discipline, raven |

| Patronage | -Against poison, against witchcraft, of agricultural workers, civil engineers,coppersmiths, dying people, Europe, farmers, fever, various other disease, Italian architects, Norcia (Italy, people in religious orders,Schoolchildren, servants who have broken their master's belongings, spelunkers, against temptations. |

Saint Benedict of Nursia(c. 480 - c. 547) was a saint from Italy, the founder of Western Christian monastic communities, and an important rule-giver for cenobitic monks. He was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church in 1220.

Benedict founded 12 communities for monks, the best known of which is his first monastery, at Monte Cassino in the mountains of southern Italy. However, he did found a distinct religious order. His purpose, as stated in his Rule, was that "Christ... may bring us all together to life eternal."

Benedict's main achievement is his "Rule," containing precepts for his monks. It is heavily influenced by the writings of John Cassian, and shows strong affinity with the Rule of the Master. Its unique spirit of balance, moderation, and reasonableness, however, persuaded most European religious communities founded throughout the Middle Ages to adopt it. As a result, the Rule of St Benedict became one of the most influential religious monastic rules in Christendom.

Because of the immense influence of his Rule, Benedict is often called the founder of western Christian monasticism. The Order of St Benedict itself is of modern origin. It not, strictly speaking, an "order" as commonly understood but a confederation of autonomous congregations under the Benedictine Rule.

Biography

The only authentic ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of Pope Gregory I's four-book Dialogues, written in 593. Gregory’s account of this saint’s life is not, however, a biography in the modern sense of the word. It provides instead a spiritual portrait of the gentle, disciplined abbot. It consists, for the most part, of a number of miraculous incidents give little help towards a chronological account of his career. Gregory's primary authorities for his account were Honoratus, abbot of the monastery at Subiaco when Gregory wrote, and Constantinus, Benedict's disciple and successor as abbot of Monte Cassino.

Early life

Benedict was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia, the modern Norcia, in Umbria, central Italy. A tradition related by the English writer Bede says the Benedict a twin, with his sister being a woman named Scholastica. His boyhood was spent in Rome, where he lived with his parents and attended the schools until he had reached his higher studies. Then, according the Gregory's account, "giving over his books, and forsaking his father's house and wealth, with a mind only to serve God, he sought for some place where he might attain to the desire of his holy purpose; and in this sort he departed [from Rome], instructed with learned ignorance and furnished with unlearned wisdom." His exact age at the time is a matter of debate, generally presumed to be between the ages 14 and 20.

Benedict does not seem to have left Rome for the purpose of becoming a hermit, but only to find some place away from the life of the great city. He took his old nurse with him as a servant and they settled down to live in Enfide, near a church dedicated to St Peter, in some kind of association with "a company of virtuous men" who were in sympathy with his spiritual feelings and his views of life. Enfide, which the tradition of the monastery at Subiaco identifies with the modern Affile, is in the Simbruini mountains, about 40 miles from Rome and two from Subiaco.

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains. The ravine soon reaches the site of a former villa of the emperor Nero. Nearby were the ruins of certain Roman baths, of which a few great arches and detached masses of wall still stand. A nearby cave about ten feet deep with a large triangular-shaped opening is traditionally believed to have served as Benedict's cell. Below, after a rapid descent lay the blue waters of a lake.

On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus of Subiaco, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus had discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and had given him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years. During this time he lived virtually unknown to men, in his cave above the lake.

During this time he was visited Romanus, who brought him food.

Later life

Through his time as a hermit, Benedict matured both in mind and character. His life of discipline and solitude also one him the respect of local Christians. On the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighborhood, identified by some with Vicovaro, the community came to him and invited him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together." However, he finally acceded to their wishes.

The experiment failed badly, however, so much so that the monks tried to poison him, and he returned to his cave. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. However, when he prayed a blessing over the cup, it miraculously shattered. Then they tried to poison his bread. This time, when he blessed the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time on his miracles are said to have become increasingly frequent. Many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be seek his guidance and learn the true way of monastic life.

For these pilgrims he caused 12 additional monasteries to be constructed in the valley, in each of which he placed a superior with 12 monks. In a thirteenth he himself lived with "a few, such as he thought would more profit and be better instructed by his own presence." He remained the abbot of all 13 cloisters. In association with the monasteries began several schools for children. Among the first to be raised under his care were the future saints Maurus and Placidus.

Benedict spent the rest of his life realizing the ideal of monasticism. To create unity and formalize discipline, he drew up his famous Rule. He died at Monte Cassino, Italy on March 21, 547.

The Benedictine Rule

A work of 73 short chapters it presents both spiritual guidance concerning how to live a life on earth centered on Christ and administrative guidelines on how to run a monastery efficiently. More than half the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the worship of God. One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed. And another tenth specifically describe the abbot’s pastoral duties. Considered in its time to be a moderate tradition representing a middle path between laxity and asceticism, it nevertheless strikes modern readers as highly disciplined in its approach. Some of its chapters deal with:

- Defining four kinds of monks: 1) Cenobites, those "in a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot"; 2) Anchorites, or hermits, who, after long successful training in a monastery live a solitary existence, 3) "Sarabaites," living by twos and threes together with no rule or superior, and thus a law unto themselves; and 4) "Gyrovagues," wandering from one monastery to another, often slaves to their own wills and appetites. It is for the first of these kinds of monks, the cenobites, as that the Rule is written (chapter 1).

Benedict describes the necessary qualifications of an abbot and forbids him to make distinctions between persons in the monastery except on the basis of merit (2). He ordains that members of the community shall be called council regarding matters of importance ( 3).

He lists 73 "tools of the spiritual craft," constituing the duties of every Christian (chapter 4) and demands prompt, ungrudging, and absolute obedience to the superior in all his lawful commands (5). While stopping short of ordaining a rule of silence, he advises moderation in the use of speech (6)

Benedict divided humility into 12 degrees, which he describes as steps in the ladder that leads to heaven (7). He divided the day into the eight canonical hours (8-19) and provided detailed instruction for the number of Psalms, prayers, and other liturgical formulas to be recited in winter and summer, on Sundays, weekdays, Holy Days, and at other times. Emphasizing the reverence owed to God, he directed that prayer must be made with heartfelt feeling rather than many words (20)

A dean is to be appointed over every ten monks (21). Each monk is to have a separate bed and is to sleep in his habit; a light shall burn in the dormitory throughout the night (22).

Benedict specifies a graduated scale of punishments for various sins: private admonition, public reproof, separation from the community at meals and other group meetings, corporal punishment, and/or finally excommunication (23-30).

Officials are to be appointed to oversee the material goods of the monastery, and no private possessions are allowed without the permission of the abbot. Monks are to take turns serving in the kitchen. Children, as well as the sick and the elderly are to have certain dispensations from the strict Rule (31-37).

Scriptural and other readings are to be done aloud during meals, during which time verbal silence is to be observed by all except the reader. Hours for the meals are prescribe—two meals a day—with two cooked dishes at each. In addition, each monk is allowed a pound of bread and a half a pint of wine per day. Meat is prohibited except for the sick and the weak (38-41)

An edifying book is to be read in the evening, and there is to be strict silence after Compline (the day's final communal gathering). Penalties are prescribe for minor faults such as coming late to prayer or meals. The abbot is to appoint chanters and readers (42-47).

* Chapter 48 emphasizes the importance of daily manual labour appropriate to the ability of the monk. The hours of labor vary with the season but are never less than five hours a day. * Chapter 49 recommends some voluntary self-denial for Lent, with the abbot's sanction. * Chapters 50 and 51 contain rules for monks working in the fields or traveling. They are directed to join in spirit, as far as possible, with their brothers in the monastery at the regular hours of prayers. * Chapter 52 commands that the oratory be used for purposes of devotion only. * Chapter 53 deals with hospitality. Guests are to be met with due courtesy by the abbot or his deputy; during their stay they are to be under the special protection of an appointed monk; they are not to associate with the rest of the community except by special permission. * Chapter 54 forbids the monks to receive letters or gifts without the abbot's leave. * Chapter 55 says clothing is to be adequate and suited to the climate and locality, at the discretion of the abbot. It must be as plain and cheap as is consistent with due economy. Each monk is to have a change of clothes to allow for washing, and when traveling is to have clothes of better quality. Old clothes are to be given to the poor. * Chapter 56 directs the abbot to eat with the guests. * Chapter 57 enjoins humility on the craftsmen of the monastery, and if their work is for sale, it shall be rather below than above the current trade price. * Chapter 58 lays down rules for the admission of new members, which is not to be made too easy. The postulant first spends a short time as a guest; then he is admitted to the novitiate where his vocation is severely tested; during this time he is always free to leave. If after twelve months' probation he perseveres, he may promise before the whole community stabilitate sua et conversatione morum suorum et oboedientia — "stability, conversion of manners, and obedience". With this vow he binds himself for life to the monastery of his profession. * Chapter 59 allows the admission of boys to the monastery under certain conditions. * Chapter 60 regulates the position of priests who join the community. They are to set an example of humility, and can only exercise their priestly functions by permission of the abbot. * Chapter 61 provides for the reception of strange monks as guests, and for their admission to the community. * Chapter 62 lays down that precedence in the community shall be determined by the date of admission, merit of life, or the appointment of the abbot. * Chapter 64 orders that the abbot be elected by his monks, and that he be chosen for his charity, zeal, and discretion. * Chapter 65 allows the appointment of a provost, or prior, but warns that he is to be entirely subject to the abbot and may be admonished, deposed, or expelled for misconduct. * Chapter 66 appoints a porter, and recommends that each monastery be self-contained and avoid intercourse with the outer world. * Chapter 67 instructs monks how to behave on a journey. * Chapter 68 orders that all cheerfully try to do whatever is commanded, however hard it may seem. * Chapter 69 forbids the monks from defending one another. * Chapter 70 prohibits them from striking one another. * Chapter 71 encourages the brothers to be obedient not only to the abbot and his officials, but also to one another. * Chapter 72 briefly exhorts the monks to zeal and fraternal charity * Chapter 73, an epilogue, declares that the Rule is not offered as an ideal of perfection, but merely as a means towards godliness, intended chiefly for beginners in the spiritual life.

Legacy

Benedict became extremely influential as his Rule came to be adopted in many monasteries of Western Christendom.

The Saint Benedict Medal

This medal originally came from a cross in honor of St Benedict. On one side, the St Benedict medal has an image of Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin is "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we, at our death, be fortified by His presence"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials for the words "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") on the vertical beam and the initials for "Non Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide") on the horizontal beam. The initial letters for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of Our Holy Father Benedict") are on the interior angles of the cross. Around the medal's margin on this side are the initials for "Vade Retro Satana, Nunquam Suade Mihi Vana—Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Begone, Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities—evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thy own poison"). Either the inscription "Pax" (Peace) or the Christogram "IHS" is located at the top of the cross in most cases.

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of St Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal; its exact origin, however, is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at Natternberg near Metten Abbey in Bavaria, the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Saint Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by Pope Benedict XIV in his briefs of December 23, 1741, and March 12, 1742.

Saint Benedict has been also the motive of many collector's coins around the world. One of the most prestigious and recent ones is the Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders', issued in March 13, 2002.

Influence

The early middle ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries."[1] In April 2008, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the influence St. Benedict had on Western Europe. The pope said that “with his life and work St. Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture” and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the Roman empire.[2]

The influence of St. Benedict produced "a true spiritual ferment" in Europe, and over the coming decades his followers spread across the continent to establish a new cultural unity based on Christian faith.

In 1964, Pope Paul VI named St. Benedict as patron saint of Europe.

He was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964. His feast day, previously 21 March, was moved in 1969 to 11 July, a date on which, in many areas, he was traditionally celebrated since the eighth century, because otherwise it would every year be impeded by the observance of Lent, during which there are no obligatory Memorials.[3]

See also

- Anthony the Great

- Benedictine Order

- Camaldolese

- Hermit

- Poustinia

Notes

- ↑ Western Europe in the Middle Ages

- ↑ Benedict XVI, "Saint Benedict of Norcia" Homily given to a general audience at St Peter's Square on Wednesday, 9 April 2008, at [1]

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), pp. 97 and 119

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

- Gold-colored small Saint Benedict crucifix.jpg

Small gold-colored St Benedict Crucifix

External links

- A Benedictine Oblate Priest - The Rule in Parish Life

- Guide to Saint Benedict

- Sacro speco, Grotta della Preghiera – general view " – enlarged view

- The Holy Rule of St. Benedict - Online translation by Rev. Boniface Verheyen, OSB, of St. Benedict's Abbey

- The Order of Saint Benedict

- The Medal Or Cross of St. Benedict: Its Origin, Meaning, and Privileges

- Life and Miracles of St Benedict

- Works by or about Benedict of Nursia in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- The Life of St. Benedict: Introduction. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.