Terracotta Army

| Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 441 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

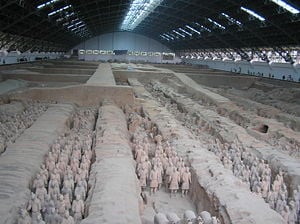

The Terracotta Army (Traditional Chinese: 兵馬俑; Simplified Chinese: 兵马俑; pinyin: bīngmǎ yǒng; literally "soldier and horse funerary statues") or Terracotta Warriors and Horses is a collection of 8,099 life-size Chinese terra cotta figures of warriors and horses located near the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor (Chinese: 秦始皇陵; pinyin: Qín Shǐhuáng líng). The figures were discovered in 1974 near Xi'an, Shaanxi province, China.

Introduction

The Terracotta Army was buried with the Emperor of Qin (Qin Shi Huangdi) in 210-209 B.C.E. (his reign over Qin was from 247 B.C.E. to 221 B.C.E. and over unified China from 221 B.C.E. to his death). Their purpose was to help rule another empire with Shi Huangdi in the afterlife. Consequently, they are also sometimes referred to as "Qin's Armies."

The Terracotta Army was discovered in March 1974 by local farmers drilling a water well to the east of Mount Lishan. (The precise coordinates are .) Mount Lishan is also where the material to make the terracotta warriors originated. In addition to the warriors, an entire man made necropolis for the emperor has been excavated.

Construction of this mausoleum began in 246 B.C.E. and is believed to have taken 700,000 workers and craftsmen 38 years to complete. Qin Shi Huangdi was interred inside the tomb complex upon his death in 210 B.C.E. According to the Grand Historian Sima Qian, the First Emperor was buried alongside great amounts of treasure and objects of craftsmanship, as well as a scale replica of the universe complete with gemmed ceilings representing the cosmos, and flowing mercury representing the great earthly bodies of water. Pearls were also placed on the ceilings in the tomb to represent the stars, planets, etc. Recent scientific work at the site has shown high levels of mercury in the soil of Mount Lishan, tentatively indicating an accurate description of the site’s contents by historian Sima Qian (145 B.C.E.-90 B.C.E.).

The tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi is near an earthen pyramid 76 meters tall and nearly 350 square meters. The tomb presently remains unopened. There are plans to seal off the area around the tomb with a special tent-type structure to prevent corrosion from exposure to outside air. However, there is at present only one company in the world that makes these tents, and their largest model will not cover the site as needed.[citation needed]

Qin Shi Huangdi’s necropolis complex was constructed to serve as an imperial compound or palace. It comprises several offices, halls and other structures and is surrounded by a wall with gateway entrances. The remains of the craftsmen working in the tomb may also be found within its confines, as it is believed they were sealed inside alive to keep them from divulging any secrets about its riches or entrance. It was only fitting, therefore, to have this compound protected by the massive terracotta army interred nearby. In July 2007 it was determined, using remote sensing technology, that the mausoleum contains a 90-foot tall building built above the tomb, with four stepped walls, each having nine steps. Researchers theorized it was built "for the soul of the emperor to depart."[1]

Construction

The terracotta figures were manufactured both in workshops by government laborers and also by local craftsmen. It is believed they were made in much the same way that terracotta drainage pipes were manufactured at the time. This would make it a factory line style of production, with specific parts manufactured and assembled after being fired as opposed to crafting one solid piece of terracotta and subsequently firing it. After completion, the terracotta figures were placed in the pits outlined above in precise military formation according to rank and duty.

The terracotta figures are life-like and life-sized. They vary in height, uniform and hairstyle in accordance with rank. The colored lacquer finish, molded faces (each is individual), and real weapons and armor used in manufacturing these figures created a realistic appearance. The weapons were stolen shortly after the creation of the army and the coloring has mostly faded. However, their existence served as a testament to the amount of labour and skill involved in their construction. It is also proof of the incredible amount of power the First Emperor possessed to order such a monumental undertaking as the manufacturing of the terracotta army. People believe that the terracota warriors were based on true people as every face has different facial features and expressions.

Destruction

There is evidence of a large fire that burned the wooden structures once housing the Terracotta Army. The fire was described by Sima Qian, who described them as the consequences of General Xiang Yu, who raided the tomb less than five years after the death of the First Emperor, as that the effects of General Xiang’s army included looting of the tomb and structures holding the Terracotta Army, as well as setting fire to the necropolis and starting a blaze that lasted for three months. Despite this fire, however, much of the remains of the Terracotta Army still survive in various stages of preservation, surrounded by remnants of the burnt wooden structures.

Today nearly two million people visit the site annually, and almost one-fifth are foreigners. The Terracotta Army now serves as both a phenomenal archaeological discovery as well as an icon of China’s distant past recognizable the world over. The power and military achievement of the First Emperor Qin Shi Huang is evident in the massive and monumental achievements present throughout his tomb complex, most notably the 8,000+ terracotta figures eternally serving to protect their leader.

In 1999, it was reported that pottery warriors were suffering from "nine different kinds of mold," caused by raised temperatures and humidity in the building which houses the soldiers, and the breath of tourists.[2] In addition, South China Morning Post reported the figures have become oxidised grey from being exposed to air, which may cause noses and hairstyles to disappear, and falling arms.[3] However, the officials dismissed the claims.[4] In Daily Planet Goes to China, the Terracotta Warriors segment reported the Chinese scientists found soot on the surface of the statue, concluding that the pollution introduced from coal burning plants was responsible for the decaying of the terracotta statues.

Terracotta Army outside China

- Forbidden Gardens, a privately funded outdoor museum in Katy, Texas has 6,000 1/3 scale replica terra-cotta soldiers displayed in formation as they were buried in the 3rd century B.C.E. Several full-size replicas are included for scale, and replicas of weapons discovered with the army are shown in a separate Weapons Room. The museum's sponsor is a Chinese businessman whose goal is to share his country's history.

- China participated in the 1982 World's Fair for the first time since 1904, displaying four terra-cotta warriors and horses from the Mausoleum.

- In 2004, an exhibit of the terracotta warriors was featured at 2004 Universal Forum of Cultures in Barcelona. It later inaugurated the Cuarto Depósito Art Center at Madrid[5]. It consisted of ten warriors, four other big figures and other pieces (totalling 170) from the Qin and Han dinasties.

- Silent Warriors, 81 original artifacts including ten soldiers are on display in Malta at the Archaeological Museum (http://www.heritagemalta.org) in Valletta till the 31st July 2007. (http://www.heritagemalta.org/documents/Silent%20Warriors.pdf)

- Twelve terra-cotta warriors, together with other figures excavated from the tomb, will move to the British Museum in London between September 2007 and April 2008.

Infiltration

On September 16, 2006, a German art student, Pablo Wendel, infiltrated a Terracotta Army exhibit in a Xi'an museum and disguised himself as one of the soldiers. According to museum officials, his disguise was good enough to make it difficult for security to discern him among the statues; he was able to hide with the Terracotta Army for several minutes before being found. However, because Wendel had no malicious intentions against the historic exhibits - he merely wanted to live out his fantasy of being one of the warriors - and he had damaged none of the statues, he was let off with only an official rebuke and no serious legal consequences. [6]

Entertainment references

- A version of the Terracotta Army was brought to life in the direct-to-DVD animated movie The Invincible Iron Man.

- The Mummy 3, scheduled to be released on July 11, 2008, will feature a sequence with the Terracotta Army[7].

- An episode of the animated Martin Mystery series featured the Terracotta Army.

- The ABC Miniseries Arabian Nights features the Terracotta army in the Aladdin story.

- The video game Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb featured terracotta soldiers as literal guardians inside Huangdi's tomb; wraiths can take control of them to attack Indiana.

- The Terracotta Army is a buildable wonder in the PC game Rise of Nations.

- In The Legend of Zelda for the Nintendo Entertainment System, Terracotta soldiers are featured guarding entrances to the games levels which are depicted as tombs. In a creative twist, these soldiers are stationary but then "come to life" if the player makes contact with the statues. It should be noted however, that these terracotta soldiers do not appear as soldiers similar to the actual terracotta army, but rather as statues with glowing eyes and swords and sheilds.

- Terry Pratchett's Discworld multi-layered fantasy satire on Western views of China Interesting Times features a final battle in which the Wizzard [sic] Rincewind takes charge of a buried terracotta army using a very science-fictiony helmet and boots with heads-up display and too many icons instead of the magic expected in the series. He gets stuck in the mud.

- The Yu-Gi-Oh!: Trading Card Game card "Mausoleum of the Emperor" is supposed to be reminiscent of the First Emperor's tomb; as such, when Astor Phoenix uses it in the Yu-Gi-Oh! GX anime, representations of the Terracotta Army are used as "tributes" to bring out his high-level monsters.

Gallery

- TERRACOTTA ARMY @ Gdynia 2006 - 01 ubt.jpeg

- TERRACOTTA ARMY @ Gdynia 2006 - 05 ubt.jpeg

- TERRACOTTA ARMY @ Gdynia 2006 - 06 ubt.jpeg

- TERRACOTTA ARMY @ Gdynia 2006 - 07 ubt.jpeg

- Officer Terrakottaarmén.jpg

- Terrakottaarmén.jpg

- P1010019.JPG

Further reading

- Debainne-Francfort, Corrine. "The Search for Ancient China," (Harry N. Abrams Inc. Pub. 1999): 91-99.

- Dillon, Michael(ed). "China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary," (Curzon Press, 1998): 196.

- Ledderose, Lothar. "A Magic Army for the Emperor." from "Ten Thousand Things : Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art" ed. Lothar Ledderose, (Princeton UP, 2000): 51-73.

- Perkins, Dorothy. "Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture," (Roundtable Press, 1999): 517-518.

- Richards, Jack C. Interchange 2, Third Edition, (Cambridge University Press, 2005):80.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ China's Terracotta Tomb Hides Mystery, AOL, 2 July 2007.

- ↑ World: Asia-Pacific Pollution threat to terracotta army

- ↑ Air pollution harms terracotta warriors

- ↑ http://www.danwei.org/media_and_advertising/is_the_terracotta_army_in_dang.php

- ↑ Los Guerreros de Xian llegan a Madrid, El Mundo, 28 September 2004.

- ↑ Story on German student infiltrating exhibit on BBC website

- ↑ Report on Mummy 3 movie having a Terracotta Warriors sequence

External links

- UNESCO description of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor

- Charles Billich created the Terracotta warriors traditional symbol as the official turtle image of the 2008 Beijing Bid. Billich's images are represented on a collection of 16 postage stamps.

- Museum of Terracotta Army Travel Guide and Photo Gallery

- The only museum outside China dedicated to Terracotta warriors - featured in Britain

- People's Daily article on the Terracotta Army

- Wide angle shot of the Terracotta Army (requires Quicktime)!

- Video from the Terracotta Army pit no. 1 - gives general view of the spot and details on the statues

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.