Madrid

| Madrid | |||

| ‚ÄĒ¬†¬†Capital city and municipality¬†¬†‚ÄĒ | |||

|

|||

| Coordinates: 40¬į25‚Ä≤N 03¬į42‚Ä≤E | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Spain | ||

| Autonomous community | Community of Madrid | ||

| Founded | Ninth century | ||

| Government | |||

|  - Type | Ayuntamiento | ||

| Area | |||

|  - Capital city and municipality | 604.31 km² (233.3 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 650 m (2,133 ft) | ||

| Population (2024) | |||

|  - Capital city and municipality | 3,223,334 | ||

|  - Metro | 6,783,000[1] | ||

|  - Metro Density | 5,300/km² (13,726.9/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

|  - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 28001‚Äď28080 | ||

| Area code(s) | +34 (ES) + 91 (M) | ||

| Website: https://madrid.es | |||

Madrid is the capital and most populous city of Spain. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU). Madrid lies on the River Manzanares in the central part of the Iberian Peninsula at about 650 meters above mean sea level. The capital city of both Spain and the surrounding autonomous community of Madrid (since 1983), it is also the political, economic, and cultural center of the country. Due to its economic output, high standard of living, and market size, Madrid is a major financial center and the leading economic hub of the Iberian Peninsula and of Southern Europe.

While Madrid possesses modern infrastructure, it has preserved the look and feel of many of its historic neighborhoods and streets. Its landmarks include the Plaza Mayor, the Royal Palace of Madrid; the Royal Theatre with its restored 1850 Opera House; the Buen Retiro Park, founded in 1631; the nineteenth-century National Library building (founded in 1712) containing some of Spain's historical archives; many national museums, and the Golden Triangle of Art, located along the Paseo del Prado and comprising three art museums: Prado Museum, the Reina Sofía Museum, a museum of modern art, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

History

The site of modern-day Madrid has been inhabited since the Paleolithic Age. Archaeological research found a sarcophagus dating to the time of the Visigoth, a Germanic people who invaded territories formerly held by the fallen Roman Empire.[2]

Middle Ages

The first historical document about the existence of an established settlement in Madrid dates from the Muslim age. In the second half of the ninth century, Umayyad Emir Muhammad I built a fortress on a headland near the river Manzanares as one of the many fortresses he ordered to be built on the border between Al-Andalus and the kingdoms of León and Castile, with the objective of protecting Toledo from the Christian invasions and also as a starting point for Muslim offensives. After the disintegration of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the early eleventh century, Madrid was integrated in the Taifa of Toledo.

In the context of the wider campaign for the conquest of the taifa of Toledo initiated in 1079, Madrid was seized in 1083 by Alfonso VI of León and Castile, who sought to use the town as an offensive outpost against the city of Toledo,[3] in turn conquered in 1085. Following the conquest, Christians occupied the center of the city, while Muslims and Jews were displaced to the suburbs. Madrid, located near Alcalá (under Muslim control until 1118), remained a borderland for a while, suffering a number of razzias during the Almoravid period, and its walls were destroyed in 1110. The city was confirmed as villa de realengo (linked to the Crown) in 1123, during the reign of Alfonso VII.[3]

The 1123 Charter of Otorgamiento established the first explicit limits between Madrid and Segovia, namely the Puerto de El Berrueco and the Puerto de Lozoya. Beginning in 1188, Madrid had the right to be a city with representation in the courts of Castile. In 1202, Alfonso VIII gave Madrid its first charter to regulate the municipal council, which was expanded in 1222 by Ferdinand III. The government system of the town was changed to a regimiento of 12 regidores by Alfonso XI on January 6, 1346.[4]

Starting in the mid-thirteenth century and up to the late fourteenth century, the concejo of Madrid vied for the control of the Real de Manzanares territory against the concejo of Segovia, a powerful town north of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountain range, characterized by its repopulating prowess and its husbandry-based economy, contrasted by the agricultural and less competent in repopulation town of Madrid.[3] After the decline of Sep√ļlveda, another concejo north of the mountain range, Segovia had become a major actor south of the Guadarrama mountains, expanding across the Lozoya and Manzanares rivers to the north of Madrid and along the Guadarrama river course to its west.[3]

In 1309, the Courts of Castile convened at Madrid for the first time under Ferdinand IV, and later in 1329, 1339, 1391, 1393, 1419, and twice in 1435.

Modern Age

During the revolt of the Comuneros, led by Juan Lopez de Padilla, Madrid joined the revolt against Charles, Holy Roman Emperor, but after defeat at the Battle of Villalar, Madrid was besieged and occupied by the imperial troops. The city was however granted the titles of Coronada (Crowned) and Imperial.

The number of urban inhabitants grew from 4,060 in the year 1530 to 37,500 in the year 1594. The poor population of the court was composed of ex-soldiers, foreigners, rogues, and Ruanes, dissatisfied with the lack of food and high prices. In June 1561 Phillip II set his court in Madrid, installing it in the old alc√°zar. Thanks to this, the city of Madrid became the political center of the monarchy, being the capital of Spain except for a short period between 1601 and 1606, in which the Court was relocated to Valladolid (and the Madrid population temporarily plummeted accordingly). Being the capital was decisive for the evolution of the city and influenced its fate and during the rest of the reign of Philip II, the population boomed, going up from about 18,000 in 1561 to 80,000 in 1598.[5]

During the early seventeenth century, although Madrid recovered from the loss of its capital status, with the return of diplomats, lords, and affluent people, as well as an entourage of noted writers and artists together with them, extreme poverty was rampant. The seventeenth century was also a time of heyday for theatre, represented in the so-called corrales de comedias.[6]

The city changed hands several times during the War of the Spanish Succession: from the Bourbon control it passed to the allied "Austracist" army with Portuguese and English presence that entered the city in late June 1706, only to be retaken by the Bourbon army on August 4, 1706. The Habsburg army led by the Archduke Charles entered the city for a second time in September 1710, leaving the city less than three months after. Philip V entered the capital on December 3, 1710.

Seeking to take advantage of the Madrid's location at the geographic center of Spain, the eighteenth century saw a sustained effort to create a radial system of communications and transports for the country through public investments.

Philip V built the Royal Palace, the Royal Tapestry Factory, and the main Royal Academies. The reign of Charles III, who came to be known as "the best mayor of Madrid," saw an effort to turn the city into a true capital, with the construction of sewers, street lighting, cemeteries outside the city, and a number of monuments and cultural institutions. The reforms enacted by his Sicilian minister were however opposed in 1766 by the populace in the so-called Esquilache Riots, a revolt demanding to repeal a clothing decree banning the use of traditional hats and long cloaks aiming to curb crime in the city.

In the context of the Peninsular War, the situation in French-occupied Madrid after March 1808 was becoming more and more tense. On May 2, a crowd began to gather near the Royal Palace protesting against the French attempt to evict the remaining members of the Bourbon royal family to Bayonne, prompting up an uprising against the French Imperial troops that lasted hours and spread throughout the city, including a famous last stand at the Monteleón barracks. Subsequent repression was brutal, with many insurgent Spaniards being summarily executed. The uprising led to a declaration of war calling all the Spaniards to fight against the French invaders.[7]

Capital of the Liberal State

The city was invaded on May 24, 1823 by a French army‚ÄĒthe so-called Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis‚ÄĒcalled to intervene to restore the absolutism of Ferdinand that the latter had been deprived from during the 1820‚Äď1823 trienio liberal. The University of Alcal√° de Henares was relocated to Madrid in 1836, becoming the Central University.

The economy of the city further modernized during the second half of the nineteenth century, consolidating its status as a service and financial center. New industries were mostly focused in book publishing, construction, and low-tech sectors. The introduction of railway transport greatly helped Madrid's economic prowess, and led to changes in consumption patterns (such as the substitution of salted fish for fresh fish from the Spanish coasts) as well as further strengthening the city's role as a logistics node in the country's distribution network. Electric lighting in the streets was introduced in the 1890s.[8]

During the first third of the twentieth century the population nearly doubled, reaching more than 850,000 inhabitants. New suburbs such as Las Ventas, Tetu√°n,and El Carmen became the homes of the influx of workers, while Ensanche became a middle-class neighborhood of Madrid.

Second Republic and Civil War

The Spanish Constitution of 1931 was the first to legislate the location of the country's capital, setting it explicitly in Madrid. During the 1930s, Madrid enjoyed "great vitality"; it was demographically young, becoming urbanized, and the center of new political movements. During this time, major construction projects were undertaken, including the northern extension of the Paseo de la Castellana, one of Madrid's major thoroughfares. The tertiary sector, including banking, insurance, and telephone services, grew greatly. The city's cultural life grew notably during the so-called Silver Age of Spanish Culture; the sales of newspapers also increased.[9]

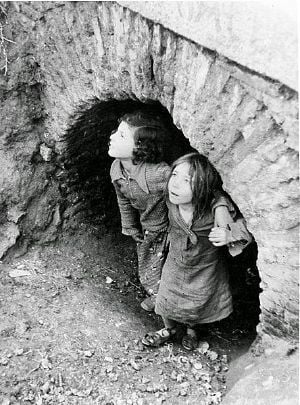

Conversely, the proclamation of the Republic created a severe housing shortage. Slums and squalor grew due to high population growth and the influx of the poor to the city. Construction of affordable housing failed to keep pace and increased political instability discouraged economic investment in housing in the years immediately prior to the Spanish Civil War. Anti-clericalism and Catholicism lived side by side in Madrid; the burning of convents initiated after riots in the city in May 1931 worsened the political environment.

Madrid was one of the most heavily affected cities in the Spanish Civil War (1936‚Äď1939). It was a stronghold of the Republican faction from July 1936 and became an international symbol of anti-fascist struggle during the conflict.[10] The city suffered aerial bombing, and in November 1936, its western suburbs were the scene of an all-out battle.[11] The city fell to the Francoists in March 1939.

Francoist dictatorship

A staple of post-war Madrid (Madrid de la posguerra) was the widespread use of ration coupons. Meat and fish consumption was scarce, resulting in high mortality due to malnutrition. Due to Madrid's history as a left-wing stronghold, the right-wing victors considered moving the capital elsewhere (most notably to Seville), but such plans were never implemented. The Franco regime instead emphasized the city's history as the capital of formerly imperial Spain.

The intense demographic growth experienced by the city via mass immigration from the rural areas of the country led to the construction of abundant housing in the peripheral areas of the city to absorb the new population (reinforcing the processes of social polarization of the city).

Madrid grew through the annexation of neighboring municipalities, achieving the present extent of 607 square kilometers (234.36 sq mi). The south of Madrid became heavily industrialized, and there was significant immigration from rural areas of Spain. Madrid's newly built north-western districts became the home of a newly enriched middle class that appeared as result of the 1960s Spanish economic boom, while the south-eastern periphery became a large working-class area, which formed the base for active cultural and political movements.[11]

Recent history

After the fall of the Francoist regime, the new 1978 constitution confirmed Madrid as the capital of Spain. The 1979 municipal election brought Madrid's first democratically elected mayor since the Second Republic to power.

Madrid was the scene of some of the most important events of the time, such as the mass demonstrations of support for democracy after the failed coup, 23-F, on February 23, 1981. The first democratic mayors belonged to the center-left PSOE (Enrique Tierno Galv√°n, Juan Barranco Gallardo). Since the late 1970s and through the 1980s Madrid became the center of the cultural movement known as la Movida.

Benefiting from increasing prosperity in the 1980s and 1990s, the capital city of Spain consolidated its position as an important economic, cultural, industrial, educational, and technological center on the European continent.[11] During the mandate as Mayor of Jos√© Mar√≠a √Ālvarez del Manzano construction of traffic tunnels below the city proliferated. The following administrations, also conservative, led by Alberto Ruiz-Gallard√≥n and Ana Botella launched three unsuccessful bids for the 2012, 2016, and 2020 Summer Olympics. By 2005, Madrid was the leading European destination for migrants from developing countries, as well as the largest employer of non-European workforce in Spain.[12]

Madrid was a center of the anti-austerity protests that erupted in Spain in 2011.[13] As consequence of the spillover of the 2008 financial and mortgage crisis, Madrid has been affected by the increasing number of second-hand homes held by banks and house evictions. The mandate of left-wing Mayor Manuela Carmena (2015‚Äď2019) delivered the renaturalization of the course of the Manzanares across the city.

Since the late 2010s, the city has faced challenges including the increasingly unaffordable rental prices (often in parallel with the gentrification and the spike of tourist apartments in the city center) and the profusion of betting shops in working-class areas, leading to an "epidemic" of gambling among young people.

Geography

Location

Madrid lies in the centre of the Iberian peninsula on the southern Meseta Central, 60 km south of the Guadarrama mountain range and straddling the Jarama and Manzanares river sub-drainage basins, in the wider Tagus River catchment area. With an average altitude of 650 m (2,130 ft), Madrid is the second highest capital of Europe (after Andorra la Vella).[14] There is a considerable difference in altitude within the city proper ranging from the 700 meters (2,297 ft) around Plaza de Castilla in the north of city to the 570 meters (1,870 ft) around La China wastewater treatment plant on the Manzanares' riverbanks, near the latter's confluence with the Fuente Castellana thalweg in the south of the city. The Monte de El Pardo (a protected forested area covering over a quarter of the municipality) reaches its top altitude (843 meters (2,766 ft)) on its perimeter, in the slopes surrounding Embalse de El Pardo located at the north-western end of the municipality, in the Fuencarral-El Pardo district.

The oldest urban core is located on the hills next to the left bank of the Manzanares River. The city grew to the east, reaching the Arroyo de la Fuente Castellana} (now the Paseo de la Castellana), and further east reaching the Arroyo Abro√Īigal (now the M-30). The city also grew through the annexation of neighboring urban settlements, including those to the South West on the right bank of the Manzanares.

Parks and forests

Madrid has the second highest number of aligned trees in the world, with 248,000 units, only exceeded by Tokyo. Madrid's citizens have access to a green area within a 15-minute walk.

A great bulk of the most important parks in Madrid are related to areas originally belonging to the royal assets (including El Pardo, Soto de Vi√Īuelas, Casa de Campo, El Buen Retiro, la Florida, and the Pr√≠ncipe P√≠o hill, and the Queen's Casino). The other main source for the "green" areas are the bienes de propios owned by the municipality (including the Dehesa de la Villa, the Dehesa de Arganzuela or Viveros).

El Retiro is the most visited location of the city. Having an area bigger than 1.4 square kilometers (0.5 sq mi) (350 acres), it is the largest park within the Almendra Central, the inner part of the city enclosed by the M-30. Created during the reign of Philip IV (seventeenth century), it was handed over to the municipality in 1868, after the Glorious Revolution. It lies next to the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid.

Located northwest of the city center, the Parque del Oeste ("Park of the West") comprises part of the area of the former royal possession of the "Real Florida." Its southern extension includes the Temple of Debod, a transported ancient Egyptian temple.[15]

Further west, across the Manzanares, lies the Casa de Campo, a large forested area with more than 1,700 hectares (6.6 sq mi) where the Madrid Zoo, and the Parque de Atracciones de Madrid amusement park are located. It was ceded to the municipality following the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931.[15]

The Monte de El Pardo is the largest forested area in the municipality. A holm oak forest covering a surface over 16,000 hectares, it is considered the best preserved mediterranean forest in the Community of Madrid and one of the best preserved in Europe. It is designated as Special Protection Area for bird-life and it is also part of the Regional Park of the High Basin of the Manzanares.[16]

Climate

Madrid has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk) transitioning to a Mediterranean Climate (Csa) in the western half. The city has continental influences.

Winters are cool due to its altitude, which is approximately 667¬†meters (2,188¬†ft) above sea level and distance from the moderating effect of the sea. While mostly sunny, rain, sporadic snowfalls and frequent frosts can occur between December and February with cooler temperatures particularly during the night and mornings as cold winds blow into the city from surrounding mountains. Summers are hot and sunny, in the warmest month, July, average temperatures during the day range from Template:Convert/Dual/LoffAoffDbSoffT depending on location, with maxima commonly climbing over 35¬†¬įC (95¬†¬įF) and occasionally up to 40¬†¬įC during the frequent heat waves. Due to Madrid's altitude and dry climate, humidity is low and diurnal ranges are often significant, particularly on sunny winter days when the temperature rises in the afternoon before rapidly plummeting after nightfall. Madrid is among the sunniest capital cities in Europe.

Precipitation is typically concentrated in the autumn and spring. Madrid is the European capital with least annual precipitation. It is particularly sparse during the summer, taking the form of about two showers and/or thunderstorms during the season.[17]

Water supply

In the seventeenth century, the viajes de agua (a kind of water channel or qanat) were used to provide water to the city. Some of the most important ones were the Viaje de Amaniel (1610‚Äď1621, sponsored by the Crown), the Viaje de la Castellana (1613‚Äď1620) and Abro√Īigal Alto/Bajo Abro√Īigal (1617‚Äď1630), sponsored by the City Council. They were the main infrastructure for the supply of water until the arrival of the Canal de Isabel II in the mid-nineteenth century.

Madrid derives almost three fourths of its water supply from dams and reservoirs built on the Lozoya River, such as the El Atazar Dam. This water supply is managed by the Canal de Isabel II, a public entity created in 1851. It is responsible for the supply, depurating waste water, and the conservation of all the natural water resources of the Madrid region.[18]

Demographics

The majority of the inhabitants of Madrid, known as Madrilenians (madrile√Īo, -√Īa), are Spanish born, while a significant number are immigrants from from Latin American countries. Most people in Madrid are Roman Catholic Christians. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Madrid.

The population of Madrid has increased overall since the city became the capital of Spain in the mid-sixteenth century; it has stabilized at approximately 3 million since the 1970s.

Government

Local government and administration

Since 2007, the Cybele Palace (or Palace of Communications) serves as City Hall.

The City Council (Ayuntamiento de Madrid) is the body responsible for the government and administration of the municipality. It is formed by the Plenary (Pleno), the Mayor (alcalde) and the Government Board (Junta de Gobierno de la Ciudad de Madrid). Madrid is divided into 21 districts, which are further subdivided into 131 neighborhoods (barrios).

The Plenary of the Ayuntamiento is the body of political representation of the citizens in the municipal government. Its 57 members are elected for a four-year mandate. Some of its attributions are: fiscal matters, the election and deposition of the mayor, the approval and modification of decrees and regulations, the approval of budgets, the agreements related to the limits and alteration of the municipal term, the services management, the participation in supramunicipal organizations, etc.[19]

The mayor, the supreme representative of the city, presides over the Ayuntamiento. He is charged with giving impetus to the municipal policies, managing the action of the rest of bodies and directing the executive municipal administration. He is responsible to the Pleno. He is also entitled to preside over the meetings of the Pleno, although this responsibility can be delegated to another municipal councilor.

The Government Board consists of the mayor, deputy mayors and a number of delegates assuming the portfolios for the different government areas. All those positions are held by municipal councilors.

Capital of Spain

Madrid is the capital of Spain. The King of Spain, the country's head of state, has his official residence in the Zarzuela Palace. As the seat of the Government of Spain, Madrid also houses the official residence of the President of the Government (Prime Minister) and regular meeting place of the Council of Ministers, the Moncloa Palace, as well as the headquarters of the ministerial departments. Both the residences of the head of state and government are located at the northwest of the city. Additionally, the seats of the Lower and Upper Chambers of the Spanish Parliament, the Cortes Generales (respectively, the Palacio de las Cortes and the Palacio del Senado), also lie in Madrid.

Regional capital

Madrid is the capital of the Community of Madrid. The region has its own legislature and enjoys a wide range of competencies in areas such as social spending, healthcare, and education. The seat of the regional parliament, the Assembly of Madrid, is located at the district of Puente de Vallecas. The presidency of the regional government is headquartered at the Royal House of the Post Office at the very center of the city, the Puerta del Sol.

Law enforcement

The Madrid Municipal Police (Policía Municipal de Madrid) is the local law enforcement body, dependent on the Ayuntamiento.

The headquarters of both the Directorate-General of the Police and the Directorate-General of the Civil Guard are located in Madrid. The headquarters of the Higher Office of Police of Madrid (Jefatura Superior de Policía de Madrid), the peripheral branch of the National Police Corps with jurisdiction over the region also lies in Madrid.

Economy

After it became the capital of Spain in the sixteenth century, Madrid was more a center of consumption than of production or trade. Economic activity was largely devoted to supplying the city's own rapidly growing population, including the royal household and national government, and to such trades as banking and publishing.

A large industrial sector did not develop until the twentieth century, but thereafter industry greatly expanded and diversified, making Madrid the second industrial city in Spain. However, the economy of the city is now becoming more and more dominated by the service sector. A major European financial center, its stock market is the third largest stock market in Europe featuring both the IBEX 35 index and the attached Latibex stock market (with the second most important index for Latin American companies).[20]

The Bank of Spain is one of the oldest European central banks. Originally named as the Bank of San Carlos as it was founded in 1782, it was later renamed to Bank of San Fernando in 1829 and ultimately became the Bank of Spain in 1856.[21] Its headquarters are located at the calle de Alcal√°.

Industry started to develop on a large scale only in the twentieth century,[22] but then grew rapidly, especially during the "Spanish miracle" period around the 1960s. Since the restoration of democracy in the late 1970s, the city has continued to expand. Its economy is now among the most dynamic and diverse in the European Union.

Present-day economy

The economy of Madrid has become based increasingly on the service sector. Nevertheless, Madrid continues to hold the position of Spain's second industrial center after Barcelona, specializing particularly in high-technology production.

Madrid and the wider region's authorities have put a notable effort in the development of logistics infrastructure. Within the city proper, some of the standout centers include Mercamadrid, the Estaci√≥n de Madrid-Abro√Īigal logistics center, the Villaverde's Logistics Center and the Vic√°lvaro's Logistics Center.

Madrid is an important center for trade fairs, many of them coordinated by IFEMA, the Trade Fair Institution of Madrid. Madrid attracts about large numbers of tourists annually from other parts of Spain and from all over the world, exceeding even Barcelona.

Media and entertainment

Madrid metropolitan area is an important film and television production hub, whose content is distributed throughout the Spanish-speaking world and abroad. It is often seen as the entry point into the European media market for Latin American media companies, and likewise the entry point into the Latin American markets for European companies. It is also the headquarters of media groups such as Radiotelevisi√≥n Espa√Īola (RTVE), Atresmedia, Mediaset Espa√Īa, and Movistar+, which produce numerous films, television shows and series which are distributed globally on various platforms.

The Torrespa√Īa broadcasting tower, located in Madrid's Salamanca district, is the central and main transmission node of the terrestrial broadcasting network in Spain. RTVE, the state-owned radio and television public broadcaster is headquartered in Pozuelo de Alarc√≥n along with all its channels and web services. Atresmedia group (Antena 3, La Sexta, Onda Cero) is headquartered in San Sebasti√°n de los Reyes. Mediaset Espa√Īa (Telecinco, Cuatro) maintains its headquarters in Madrid's Fuencarral-El Pardo district. Together with RTVE, Atresmedia and Mediaset account for nearly the 80% of share of generalist television. The Spanish media conglomerate PRISA (Cadena SER, Los 40 Principales, M80 Radio, Cadena Dial) is headquartered in Gran V√≠a street in central Madrid.

Besides hosting the main television and radio producers and broadcasters, the metropolitan area hosts most of the major written mass media in Spain, including ABC, El País, El Mundo, La Razón, Marca, ¡Hola!, Diario AS, El Confidencial and Cinco Días. The Spanish international news agency EFE maintains its headquarters in Madrid since its inception in 1939. The second news agency of Spain is the privately owned Europa Press, founded and headquartered in Madrid since 1953.

Culture

Architecture

Little medieval architecture is preserved in Madrid, mostly in the Almendra Central, including the San Nicolás and San Pedro el Viejo church towers, the church of San Jerónimo el Real, and the Bishop's Chapel. Nor has Madrid retained much Renaissance architecture, other than the Bridge of Segovia and the Convent of Las Descalzas Reales.

Philip II moved his court to Madrid in 1561 and transformed the town into a capital city. During the Early Hapsburg period, the import of European influences took place, underpinned by the monicker of "Austrian style." The Austrian style featured not only Austrian influences but also Italian and Dutch (as well as Spanish), reflecting the international preeminence of the Habsburgs.[23] During the second half of the sixteenth century, the use of slate spires in order to top structures such as church towers was imported to Spain from Central Europe. Slate spires and roofs consequently became a staple of the Madrilenian architecture at the time.

Stand out architecture in the city dating back to the early seventeenth century includes several buildings and structures (most of them attributed to Juan G√≥mez de Mora) such as the Palace of the Duke of Uceda (1610), the Monastery of La Encarnaci√≥n (1611‚Äď1616); the Plaza Mayor (1617‚Äď1619) or the C√°rcel de Corte (1629‚Äď1641), currently known as the Santa Cruz Palace. The century also saw the construction of the former City Hall, the Casa de la Villa.[23]

The Imperial College church model dome was imitated in all of Spain. Pedro de Ribera introduced Churrigueresque architecture to Madrid; the Cuartel del Conde-Duque, the church of Montserrat, and the Bridge of Toledo are among the best examples.

The reign of the Bourbons during the eighteenth century marked a new era in the city. Philip V tried to complete King Philip II's vision of urbanization of Madrid. Philip V built a palace in line with French taste, as well as other buildings such as St. Michael's Basilica and the Church of Santa B√°rbara. King Charles III beautified the city and endeavored to convert Madrid into one of the great European capitals. He pushed forward the construction of the Prado Museum (originally intended as a Natural Science Museum), the Puerta de Alcal√°, the Royal Observatory, the Basilica of San Francisco el Grande, the Casa de Correos in Puerta del Sol, the Real Casa de la Aduana, and the General Hospital (which now houses the Reina Sofia Museum and Royal Conservatory of Music). The Paseo del Prado, surrounded by gardens and decorated with neoclassical statues, is an example of urban planning. The Duke of Berwick ordered the construction of the Liria Palace.

During the early nineteenth century, the Peninsular War, the loss of viceroyalties in the Americas, and continuing coups limited the city's architectural development.

From the mid-nineteenth century until the Civil War, Madrid modernized and built new neighborhoods and monuments. The expansion of Madrid developed under the Plan Castro, resulting in the neighborhoods of Salamanca, Arg√ľelles, and Chamber√≠. Arturo Soria conceived the linear city and built the first few kilometers of the road that bears his name, which embodies the idea. The Gran V√≠a was built using different styles that evolved over time: French style, eclectic, art deco, and expressionist. However, Art Nouveau in Madrid, known as Modernismo did also develop at the turn of the century, in concert with its appearance elsewhere in Europe, including Barcelona and Valencia. Antonio Palacios built a series of buildings inspired by the Viennese Secession, such as the Palace of Communication, the C√≠rculo de Bellas Artes, and the R√≠o de La Plata Bank (now Instituto Cervantes). Other notable buildings include the Bank of Spain, the neo-Gothic Almudena Cathedral, Atocha Station, and the Catalan art-nouveau Palace of Longoria. Las Ventas Bullring was built, as the Market of San Miguel (Cast-Iron style).

Following the Francoist takeover that ensued the end of Spanish Civil war, architecture experienced an involution, discarding rationalism and, eclecticism notwithstanding, going back to an overall rather "outmoded" architectural language, with the purpose of turning Madrid into a capital worthy of the "Immortal Spain." Iconic examples of this period include the Ministry of the Air and the Edificio Espa√Īa. Many of these buildings distinctly combine the use of brick and stone in the fa√ßades.

With the advent of Spanish economic development, skyscrapers, such as Torre Picasso, Torres Blancas and Torre BBVA, and the Gate of Europe, appeared in the late twentieth century in the city. During the decade of the 2000s, the four tallest skyscrapers in Spain were built and together form the Cuatro Torres Business Area. Terminal 4 at Madrid-Barajas Airport was inaugurated in 2006 and won several architectural awards. It features glass panes and domes in the roof, which allow natural light to pass through.

Museums and cultural centers

Madrid is considered one of the top European destinations concerning art museums. Best known is the Golden Triangle of Art, located along the Paseo del Prado and comprising three major museums: the Prado Museum, the Reina Sofía Museum, and the Thyssen Bornemisza Museum.

The Prado Museum (Museo del Prado) is a museum and art gallery that features one of the world's finest collections of European art, from the twelfth century to the early nineteenth century, based on the former Spanish Royal Collection. It has the best collection of artworks by Goya, Vel√°zquez, El Greco, Rubens, Titian, Hieronymus Bosch, Jos√© de Ribera, and Patinir as well as works by Rogier van der Weyden, Raphael Sanzio, Tintoretto, Veronese, Caravaggio, Van Dyck, Albrecht D√ľrer, Claude Lorrain, Murillo, and Zurbar√°n, among others. Some of the standout works exhibited at the museum include Las Meninas, La maja vestida, La maja desnuda, The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Immaculate Conception and The Judgement of Paris.[24]

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza) is an art museum that fills the historical gaps in its counterparts' collections: in the Prado's case, this includes Italian primitives and works from the English, Dutch, and German schools, while in the case of the Reina Sofía, the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, includes Impressionists, Expressionists, and European and American paintings from the second half of the twentieth century.[25]

The Reina Sofía National Art Museum (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía; MNCARS) is Madrid's national museum of twentieth-century art and houses Pablo Picasso's 1937 anti-war masterpiece, Guernica. Other highlights of the museum, which is mainly dedicated to Spanish art, include excellent collections of Spain's greatest twentieth-century masters including Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Picasso, Juan Gris, and Julio González. The Reina Sofía also hosts a free-access art library.[26]

The National Archaeological Museum of Madrid (Museo Arqueológico Nacional) shows archaeological finds from Prehistory to the nineteenth century (including Roman mosaics, Greek ceramics, Islamic art, and Romanesque art), especially from the Iberian Peninsula, distributed over three floors. An iconic item in the museum is the Lady of Elche, an Iberian bust from the fourth century B.C.E. Other major pieces include the Lady of Baza, the Lady of Cerro de los Santos, the Lady of Ibiza, the Bicha of Balazote, the Treasure of Guarrazar, the Pyxis of Zamora, the Mausoleum of Pozo Moro or a napier's bones. In addition, the museum has a reproduction of the polychromatic paintings in the Altamira Cave.

The Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando) houses a fine art collection of paintings ranging the fifteenth to twentieth centuries. The academy is also the headquarters of the Madrid Academy of Art. Francisco Goya was once one of the academy's directors, and its alumni include Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Antonio López García, Juan Luna, and Fernando Botero.[27]

The Royal Palace of Madrid, a massive building characterized by its luxurious rooms, houses rich collections of armors and weapons, as well as the most comprehensive collection of Stradivarius in the world.[28]

The Museum of the Americas (Museo de América) is a national museum that holds artistic, archaeological, and ethnographic collections from the Americas, ranging from the Paleolithic period to the present day.[29]

Other notable museums include the National Museum of Natural Sciences (the Spain's national museum of natural history), the Naval Museum, the Convent of Las Descalzas Reales (with many works of Renaissance and Baroque art, and Brussels tapestries inspired by paintings of Rubens), the Museum of L√°zaro Galdiano (housing a collection specializing in decorative arts, featuring a collection of weapons that features the sword of Pope Innocent VIII), the National Museum of Decorative Arts, the National Museum of Romanticism (focused on nineteenth century Romanticism), the Museum Cerralbo, the National Museum of Anthropology (featuring as highlight a Guanche mummy from Tenerife), the Sorolla Museum, and the History Museum of Madrid (housing pieces related to the local history of Madrid), the Wax Museum of Madrid, the Railway Museum (located in the building that was once the Delicias Station), and CaixaForum Madrid, a post-modern art gallery in the center of Madrid, next to the Prado Museum.

Major cultural centers in the city include the Fine Arts Circle (one of Madrid's oldest arts centers and one of the most important private cultural centres in Europe, hosting exhibitions, shows, film screenings, conferences and workshops), the Conde Duque cultural center or the Matadero Madrid, a cultural complex (formerly an abattoir) located by the river Manzanares. The Matadero, created in 2006 with the aim of "promoting research, production, learning, and diffusion of creative works and contemporary thought in all their manifestations," is considered the third most valued cultural institution in Madrid among art professionals.[30]

Literature

Madrid has been one of the great centers of Spanish literature. Some of the most distinguished writers of the Spanish Golden Age were born in Madrid, including Lope de Vega (author of Fuenteovejuna and The Dog in the Manger), who reformed the Spanish theatre, a project continued by Calderon de la Barca (author of Life is a Dream). Francisco de Quevedo, who criticized the Spanish society of his day, and author of El Buscón, and Tirso de Molina, who created the character Don Juan, were born in Madrid. Cervantes and Góngora also lived in the city, although they were not born there. The Madrid homes of Lope de Vega, Quevedo, Gongora, and Cervantes still exist, and they are all in the Barrio de las Letras (Literary Neighborhood).

At 87 Calle de Atocha, in the northern end of the Barrio de las Letras, was the printing house of Juan de la Cuesta, where the first edition of Don Quixote was typeset and printed in 1604.

Other writers born in Madrid in later centuries have been Leandro Fernandez de Moratín, Mariano José de Larra, Jose de Echegaray (Nobel Prize in Literature), Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Dámaso Alonso, Enrique Jardiel Poncela, and Pedro Salinas.

Madrid is home to the Royal Spanish Academy, the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language, which governs, with statutory authority, over Spanish, preparing, publishing, and updating authoritative reference works on it. The academy's motto (lema, in Spanish) states its purpose: it cleanses the language, stabilizes it, and gives it brilliance ("Limpia, fija y da resplendor").[31] Madrid is also home to another international cultural institution, the Instituto Cervantes, whose task is the promotion and teaching of the Spanish language as well as the dissemination of the culture of Spain and Hispanic America.

Cuisine

Madrilenian cuisine is greatly influenced by other regions of Spain and its own identity actually relies in its ability to assimilate elements from other cuisines.

The cocido madrile√Īo, a chickpea-based stew, is one of the most emblematic dishes of the Madrilenian cuisine. The callos a la madrile√Īa is another traditional winter specialty, usually made of cattle tripes. Other offal dishes typical in the city include the gallinejas or grilled pig's ear. Fried squid has become a culinary specialty in Madrid, often consumed in a sandwich: bocata de calamares.[32]

Other generic dishes commonly accepted as part of the Madrilenian cuisine include the potaje, the sopa de ajo (Garlic soup), the Spanish omelette, the besugo a la madrile√Īa (bream), caracoles a la madrile√Īa (snails, sp. Cornu aspersum) or the soldaditos de Pav√≠a, the patatas bravas (consumed as snack in bars) or the gallina en pepitoria (hen or chicken cooked with the yolk of hard-boiled eggs and almonds).

Traditional desserts, usually served at Easter, include torrijas, a Spanish version of the classic French toast,[32] and bartolillos, a triangular pastry.[33]

Nightlife

Madrid is an international hub of highly active and diverse nightlife with bars, dance bars, and nightclubs staying open well past midnight.[34] Some of the highlight bustling locations include the surroundings of the Plaza de Santa Ana, Malasa√Īa, and La Latina (particularly near the Calle de la Cava Baja, one of the city's main attractions with tapas bars, cocktail bars, clubs, jazz lounges, live music venues, and flamenco theatres.

Classical music and opera

The Auditorio Nacional de M√ļsica is the main venue for classical music concerts in Madrid. It is home to the Spanish National Orchestra, the Chamart√≠n Symphony Orchestra and the venue for the symphonic concerts of the Community of Madrid Orchestra and the Madrid Symphony Orchestra. It is also the principal venue for orchestras on tour playing in Madrid.

The Teatro Real is the main opera house in Madrid, located just in front of the Royal Palace, and its resident orchestra is the Madrid Symphony Orchestra. The theatre stages around seventeen opera titles (both own productions and co-productions with other major European opera houses) per year, as well as two or three major ballets and several recitals.

The Teatro de la Zarzuela is mainly devoted to Zarzuela (the Spanish traditional musical theatre genre), as well as operetta and recitals. The resident orchestra of the theatre is the Community of Madrid Orchestra.

The Teatro Monumental is the concert venue of the RTVE Symphony Orchestra. Other concert venues for classical music are the Fundación Joan March and the Auditorio 400, devoted to contemporary music.

Feasts and festivals

The local feast par excellence is the Day of Isidore the Laborer (San Isidro Labrador), the patron Saint of Madrid, celebrated on May 15. It is a public holiday. According to tradition, Isidro was a farmworker and well manufacturer born in Madrid in the late eleventh century, who lived a pious life and whose corpse was reportedly found to be incorrupt in 1212. Already very popular among the madrilenian people, as Madrid became the capital of the Hispanic Monarchy in 1561 the city council pulled efforts to promote his canonization; the process started in 1562. Isidro was beatified in 1619 and the feast day set on May 15 (he was finally canonized in 1622).[35]

Other holidays include the regional day (May 2) commemorating the Dos de Mayo Uprising (a public holiday), the feasts of San Antonio de la Florida (June 13), the feast of the Virgen de la Paloma (circa August 15) or the day of the co-patron of Madrid, the Virgin of Almudena (November 9), although the latter's celebrations are rather religious in nature.

The most important musical event in the city is the Mad Cool festival, created in 2016[36]

Bullfighting

Madrid hosts the largest plaza de toros (bullring) in Spain, Las Ventas, established in 1929. Las Ventas is considered by many to be the world centre of bullfighting and has a seating capacity of almost 25,000. Madrid's bullfighting season begins in March and ends in October. Bullfights are held every day during the festivities of San Isidro (Madrid's patron saint) from mid May to early June, and every Sunday, and public holiday, the rest of the season.

Las Ventas also hosts music concerts and other events outside of the bullfighting season.

Sport

Football

Football (soccer) is the most popular sport, both in terms of participants and spectators, in Madrid.

Real Madrid, founded in 1902, compete in La Liga and play their home games at the Santiago Bernabéu Stadium. The club is one of the most widely supported teams in the world and their supporters are referred to as Madridistas or Merengues (Meringues). The club was selected as the best club of the twentieth century, being the most successful Spanish football club with a total of 100 official titles (this includes a record 14 European Cups and a record 35 La Ligas).

Atlético Madrid, founded in 1903, also compete in La Liga and play their home games at the Metropolitano Stadium. The club is well-supported in the city, having the third national fan base in Spain and their supporters are referred to as Atléticos or Colchoneros (The Mattressers). The club is considered an elite European team, having won three UEFA Europa League titles and reached three European Cup finals. Domestically, Atletico have won eleven league titles and ten Copa del Reys.

Madrid hosted five European Cup/Champions League finals, four at the Santiago Bernabéu, and the 2019 final at the Metropolitano. The Bernabéu also hosted the Euro 1964 Final (which Spain won) and 1982 FIFA World Cup Final.

Basketball

Real Madrid Baloncesto, founded in 1931, compete in Liga ACB and play their home games at the Palacio de Deportes (WiZink Center). Real Madrid's basketball section, similarly to its football team, is the most successful team in Europe, with a record 11 EuroLeague titles. Domestically, they have clinched a record 36 league titles and a record 28 Copa del Reys.

Club Baloncesto Estudiantes, founded in 1948, compete in LEB Oro and also play their home games at the Palacio de Deportes (WiZink Center).

Madrid has hosted six European Cup/EuroLeague finals, the last two at the Palacio de Deportes. The city also hosted the final matches for the 1986 and 2014 FIBA World Cups, and the EuroBasket 2007 final (all held at the Palacio de Deportes).

Events

The main annual international event in cycling, the Vuelta a Espa√Īa (La Vuelta), is one of the three worldwide prestigious three-week-long Grand Tours, and its final stages takes place in Madrid on the first Sunday of September.

In tennis, the city hosts Madrid Open, both male and female versions, played on clay courts. The event is part of the nine ATP Masters 1000 and nine WTA 1000 tournaments. It is held during the first week of May in the Caja M√°gica. Additionally, Madrid hosts the finals of the major tournament for men's national teams, Davis Cup, since 2019.

Education

Madrid is home to many public and private universities. Some of them are among the oldest in the world, and many of them are the most prestigious universities in Spain.

The National Distance Education University (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia; UNED) has as its mission the public service of higher education through the modality of distance education. UNED has the largest student population in Spain and is one of the largest universities in Europe.

The Complutense University of Madrid (Universidad Complutense de Madrid; UCM) is the second largest university in Spain after UNED and one of the oldest universities in the world. It is located on two campuses, the main one of Ciudad Universitaria in the Moncloa-Aravaca district, and the secondary campus of Somosaguas, founded in 1971, located outside the city limits in Pozuelo de Alarcón. The Complutense University of Madrid was founded in Alcalá de Henares, old Complutum, by Cardinal Cisneros in 1499. Nevertherless, its real origin dates back to 1293, when King Sancho IV of Castile built the General Schools of Alcalá, which would give rise to Cisnero's Complutense University. In 1836, during the reign of Isabel II, the university was moved to Madrid, where it took the name of Central University and was located at San Bernardo Street. In 1970 the Government reformed the High Education, and the Central University became the Complutense University of Madrid. It was then when the new campus at Somosaguas was created to house the new School of Social Sciences. The old Alcalá campus was reopened as the independent UAH, University of Alcalá, in 1977. Complutense also serves to the population of students who select Madrid as their residency during their study abroad period.

The Technical University of Madrid (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid; UPM), is the top technical university in Spain. It is the result of the merger of different Technical Schools of Engineering. It shares the Ciudad Universitaria campus with the UCM, while it also owns several schools scattered in the city center and additional campuses in the Puente de Vallecas district and in the neighboring municipality of Boadilla del Monte.

The Autonomous University of Madrid (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; UAM) is widely recognized for its research strengths in theoretical physics. Known simply as La Autónoma by locals, its main site is the Cantoblanco Campus, located at the North of the municipality, close to its boundaries with the neighboring municipalities of Alcobendas, San Sebastián de los Reyes and Tres Cantos. The Medical School is located outside the main site, beside the Hospital Universitario La Paz.

The private Comillas Pontifical University (Universidad Pontificia Comillas; UPC) has its rectorate and several faculties in Madrid. The private Nebrija University is also based in Madrid. Some of the big public universities headquartered in the surrounding municipalities also have secondary campuses in Madrid proper: the Charles III University of Madrid (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid; UC3M) with its main site in Getafe and an educational facility in Embajadores, and the King Juan Carlos University (Universidad Rey Juan Carlos; URJC) having its main site in Móstoles and a secondary campus in Vicálvaro. The private Camilo José Cela University (Universidad Camilo José Cela; UCJC) has a postgrade school in Chamberí.

IE Business School (formerly Instituto de Empresa) has its main campus on the border of the Chamartín and Salamanca districts of Madrid. Although based in Barcelona, both IESE Business School and ESADE Business School also have Madrid campuses. These three schools are the top-ranked business schools in Spain, consistently rank among the top 20 business schools globally, and offer MBA programs (in English or Spanish) as well as other business degrees.

Transportation

Madrid is served by several roads and three modes of public surface transportation; additionally there are two airports. A great many important road, rail and air links converge on the capital, providing effective connections with other parts of the metropolitan region and with the rest of Spain and other parts of Europe.

Road transport

Madrid is the center of the most important roads of Spain. Already in 1720, the Reglamento General de Postas enacted by Philip V configured the basis of a radial system of roads in the country. Madrid features a number of the most prominent autovías (fast dual highways), part of the Red de Carreteras del Estado. Due to the large amount of traffic, new toll highways were built parallel to the main national freeways.

The Madrid road network also includes four orbital ones at different distances from the center.

Public transport

There are four major components of public transport, with many intermodal interchanges.

The Metro is the rapid transit system serving Madrid as well as some suburbs. Founded in 1919, it underwent extensive enlargement in the second half of the twentieth century. It is the third longest metro system in Europe (after Moscow and London).

Cercanías Madrid is the commuter rail service used for longer distances from the suburbs and beyond into Madrid, consisting of nine lines totaling 578 kilometers (359 mi) and more than 90 stations. With fewer stops inside the center of the city they are faster than the Metro, but run less frequently.

There is a dense network of bus routes, run by the municipal company Empresa Municipal de Transportes (or EMT Madrid), which operates 24 hours a day; special services called "N lines" are run during nighttime. The special Airport Express Shuttle line connecting the airport with the city center features distinctively yellow buses. In addition to the urban lines operated by the EMT, the green buses (interurbanos) connect the city with the suburbs. The later lines, while also regulated by the CRTM, are often run by private operators.

The taxicabs are regulated by a specific sub-division of taxi service, a body dependent of the Madrid City Council.

Long-distance transport

In terms of longer-distance transport, Madrid is the central node of the system of autov√≠as, giving the city direct fast road links with most parts of Spain and with France and Portugal. It is also the focal point of one of the world's three largest high-speed rail systems, Alta Velocidad Espa√Īola (AVE), which has brought major cities such as Seville and Barcelona within 2.5 hours travel time.

Aside from the local and regional bus commuting services, Madrid is also a node for long-distance bus connections to Spanish destinations as well as international bus connections to cities in Morocco as well as to diverse European destinations.

Airport

Madrid is also home to the Madrid-Barajas Airport, the sixth-largest airport in Europe, handling over 60 million passengers annually, of whom 70 percent are international travelers, in addition to the majority of Spain's air freight movements. Barajas is a major European hub, yet a largely westward facing one, specialized in the Americas, with a comparatively lighter connectivity to Asia. Madrid's location at the center of the Iberian Peninsula makes it a major logistics base.

The smaller (and older) Cuatro Vientos Airport has a dual military-civilian use and hosts several aviation schools. The Torrejón Air Base, located in the neighboring municipality of Torrejón de Ardoz, also has a secondary civilian use aside from the military purpose.

International relations

Madrid hosts 121 foreign embassies, comprising the totality of resident embassies in the country. The headquarters of the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation, the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation and the Diplomatic School are also located in the city.

Madrid also hosts the seat of international organizations such as the United Nations' World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the Ibero-American General Secretariat (SEGIB), the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI), the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the Club of Madrid and the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).

Madrid has twin towns, sister city 'agreements' (acuerdos) and sister city 'minutes' (actas) with several cities around the world. Madrid is part of the Union of Ibero-American Capital Cities, establishing brotherly relations with several cities.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Madrid, Spain Metro Area Population 1950-2024 Macro Trends. Retrieved Februry 5, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Isis Davis-Marks, Well-Preserved Visigoth Sarcophagus Found at Roman Villa in Spain Smithsonian Magazine (July 28, 2021). Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 √Āngel Bahamonde Magro y Luis Enrique Otero Carvajal, Madrid, de territorio fronterizo a regi√≥n metropolitana Espa√Īa: Autonom√≠as (Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1989). Retrieved February 5, 2024).

- ‚ÜĎ Antonio L√≥pez G√≥mez (ed.), Madrid desde la Academia (Real Academia de la Historia, 2001, ISBN 978-8489512818).

- ‚ÜĎ Deborah L. Parsons, A Cultural History of Madrid: Modernism and the Urban Spectacle (Berg Publishers, 2003, ISBN 978-1859736517).

- ‚ÜĎ Dosier: El barrio de las letras y las mujeres Revista Madrid Hist√≥rico (July 3, 2019). Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Jon Cowans (ed.), Modern Spain: A Documentary History (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0812237177).

- ‚ÜĎ Jules Stewart, Madrid: The History (I.B. Tauris, 2013, ISBN 978-1780762814).

- ‚ÜĎ Jeffrey Zamostny and Susan Larson (eds.), Kiosk Literature of Silver Age Spain: Modernity and Mass Culture (Intellect Ltd, 2017, ISBN 978-1783206650).

- ‚ÜĎ Rafael Villena Espinosa and Jos√© Manuel L√≥pez Tor√°n (eds.), Fotograf√≠a y patrimonio cultural: V, VI y VVI Encuentros en Castilla-La Mancha (Ediciones de la UCLM, 2018, ISBN 978-8490443330).

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Jes√ļs A. Mart√≠nez Mart√≠n and Luis Enrique Otero Carvajal, La sociedad urbana en el Madrid contempor√°neo (Los Libros de la Catarata, 2018, ISBN 978-8490974650).

- ‚ÜĎ Araceli Masterson-Algar, Ecuadorians in Madrid: Migrants' Place in Urban History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, ISBN 978-1137536068).

- ‚ÜĎ Ten years after Spain's indignados protests The Economist ( May 6, 2021). Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Enrique √Āvila L√≥pez, Modern Spain (ABC-CLIO, 2015, ISBN 978-1610696005).

- ‚ÜĎ 15.0 15.1 Natalia Diaz, Madrid‚Äôs best parks for sightseeing Lonely Planet, July 12, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ El Pardo Woodlands Patrimonio Nacional. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Climate in Madrid (Spain) WorldData. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Canal de Isabel II. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ El Pleno Portal web del Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Andrew Lynch (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Spanish in the Global City. (Routledge, 2021, ISBN 978-0367783822).

- ‚ÜĎ Pablo Mart√≠n-Ace√Īa, The Banco de Espa√Īa, 1782‚Äď2017: The history of a central bank Estudios de Historia Econ√≥mica 73 (2017). Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Santos Juli√† D√≠ez, David R. Ringrose, and Cristina Segura, Madrid, Historia de una capital (Alianza Editorial, 2006, ISBN 978-8420636009).

- ‚ÜĎ 23.0 23.1 Jes√ļs Escobar, Habsburg Madrid: Architecture and the Spanish Monarchy (Penn State University Press, 2022, ISBN 978-0271091419).

- ‚ÜĎ Museo del Prado. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Museo Reina Sof√≠a (MNCARS). Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Palacio Real de Madrid Patrimonio Nacional. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Museo de Am√©rica. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Matadero Madrid, la tercera instituci√≥n cultural mejor valorada del pa√≠s El Pa√≠s (March 10, 2014). Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Luca P. De Cristofaro, The Authority of the Real Academia Espa√Īola in Global Spanish United Citizens of Europe, September 30, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 32.0 32.1 Top 7 Madrilenian Foods Taste Atlas, December 1, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Foods to Eat in Spain - Madrid Food of the World. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Connor McGovern, The real city that never sleeps: discovering nightlife in Madrid National Geographic (February 22, 2021). Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ ¬ŅPor qu√© se celebra San Isidro el 15 de mayo? La Sexta, May 15, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Mad Cool Festival. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- √Āvila L√≥pez, Enrique. Modern Spain. ABC-CLIO, 2015. ISBN 978-1610696005

- Cowans, Jon (ed.). Modern Spain: A Documentary History. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0812237177

- Julià Díez, Santos, David R. Ringrose, and Cristina Segura, Madrid, Historia de una capital. Alianza Editorial, 2006. ISBN 978-8420636009

- López Gómez, Antonio (ed.). Madrid desde la Academia. Real Academia de la Historia, 2001. ISBN 978-8489512818

- Lynch, Andrew (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Spanish in the Global City. Routledge, 2021. ISBN 978-0367783822

- Mart√≠nez Mart√≠n, Jes√ļs A., and Luis Enrique Otero Carvajal. La sociedad urbana en el Madrid contempor√°neo. Los Libros de la Catarata, 2018. ISBN 978-8490974650

- Masterson-Algar, Araceli. Ecuadorians in Madrid: Migrants' Place in Urban History.Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. ISBN 978-1137536068

- Parsons, Deborah L. A Cultural History of Madrid: Modernism and the Urban Spectacle. Berg Publishers, 2003. ISBN 978-1859736517

- Stewart, Jules. Madrid: The History. I.B. Tauris, 2013. ISBN 978-1780762814

- Villena Espinosa, Rafael, and José Manuel López Torán (eds.). Fotografía y patrimonio cultural: V, VI y VVI Encuentros en Castilla-La Mancha. Ediciones de la UCLM, 2018. ISBN 978-8490443330

- Zamostny, Jeffrey, and Susan Larson (eds.). Kiosk Literature of Silver Age Spain: Modernity and Mass Culture. Intellect Ltd, 2017. ISBN 978-1783206650

External links

All links retrieved March 27, 2025.

- Turismo Madrid: Official tourism website

- Official Madrid Tourism website

- Tourism in Madrid

- Madrid Travel Guide Conde Nast Traveler

- Madrid Lonely Planet

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.