Sable

| Sable | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Martes zibellina Linnaeus, 1758 |

The sable (Martes zibellina) is a small carnivorous mammal, closely related to the martens. It inhabits forest environments primarily in Russia from the Ural Mountains throughout Siberia, in northern Mongolia and China and on Hokkaidō in Japan.[1] Its range in the wild originally extended through European Russia to Poland and Scandinavia.[2] It has historically been harvested for its highly valued fur, which remains a luxury good to this day. While hunting of wild animals is still common in Russia, most fur in the market is now commercially farmed.

Overview

Family Mustelidae and genus Martes

Weasels are member of the mammalian order Carnivora, which includes such familiar groups as dogs, cats, bears, and seals. There are over 260 species in Carnivora, which are divided into two main sub-orders: Feliformia (cat-like) and Caniformia (dog-like). The weasel family, Mustelidae, belongs to the subgroup Caniformia, which includes such major sub-groups as the families Canidae (dogs, wolves, and foxes), Ursidae (bears), and Mephitidae (skunks), as well as the pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, and walruses).

The Mustelidae family includes 55 species of weasels, badgers, and otters), placed in 24 genera. This "weasel family" is a diverse family and the largest in the order Carnivora, at least partly because it has in the past been a catch-all category for many early or poorly differentiated taxa.

Mustelids (members of the Mustelidae family) vary greatly in size and behavior. The least weasel is not much larger than a mouse. The giant otter can weigh up to 76 lb (34 kg). The wolverine can crush bones as thick as the femur of a moose to get at the marrow, and has been seen attempting to drive bears from kills. The sea otter uses rocks to break open shellfish to eat. The marten is largely arboreal, while the badger digs extensive networks of tunnels, called setts. Within a large range of variation, the mustelids exhibit some common characteristics. They are typically small animals with short legs, short round ears, and thick fur.

The Martens constitute the genus Martes within the subfamily Mustelinae, in family Mustelidae. They are slender, agile, animals, adapted to living in taigas, and are found in coniferous and northern deciduous forests across the northern hemisphere. They have bushy tails, and large paws with partially retractile claws. The fur varies from yellowish to dark brown, depending on the species, and, in many cases, is valued by fur trappers. Martens are carnivorous animals related to wolverines, minks and weasels.

Sable

Males weigh 880-1800 grams and have body length between 380-560 mm, with relatively long tails between 90-120 mm. Males are somewhat larger than females (700-1560 grams, 350-510 mm).[3] Winter pelage is longer and thicker than their summer coat. Coloration varies in color from tan to black.[2] The fur is somewhat lighter ventrally and a patch of gray, white, or pale yellow fur on the throat is common. The finest, darkest fur is highly prized and referred to as "black diamond".

The name sable appears to be of Slavic origin and to have entered most Western European via the early medieval fur trade.[4] Thus the Russian and Polish sobol became the German Zobel, Dutch Sabel; the French zibelline Spanish cibelina, cebellina, Finnish soopeli and Mediaeval Latin zibellina derive from the Italian form. The English and Medieval Latin word sabellum comes from the Old French sable or saible.

The term has become a generic description for some black-furred animal breeds, such as sable cats or rabbits.

Behavior, habitat and ecology

Sables are diurnal predators, using their sense of smell and hearing to hunt for small prey. They have been observed to hide in their dens for days during periods such as snow storms, or when they are being hunted by humans. In the wild they are potentially vicious; although there are "domesticated" sables who have been described as playful, curious, and even "tame" (if taken from their mother at a young age). They are mostly terrestrial, hunting and constructing dens on the forest floor. They feed on chipmunks, squirrels, mice, small birds and fish. When primary sources are scarce they eat berries, vegetation, and pine nuts. When weather conditions are extreme they will store their prey in their den. Despite their small size, their sharp teeth and fierce demeanor discourage most predators.

History of exploitation and status

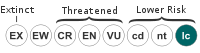

Sable fur has been a highly valued item in the fur trade since the early Middle Ages. Intensified hunting in Russia in the 19th and early 20th century caused a severe enough decline in numbers that a five year ban on hunting was instituted in 1935, followed by a winter-limited licensed hunt. These restrictions together with the development of sable farms have allowed to species to recolonize much of its former range and attain healthy numbers.[5] The collapse of the Soviet Union led to an increase of hunting and poaching in the 1990s, in part because wild caught Russian furs are considered the most luxurious and demand the highest prices on the international market.[6] Currently, the species has no special conservation status according to the IUCN, though the isolated Japanese subspecies M. zibellina brachyurus is listed as "data-deficient".[7]

Because of its great expense, sable fur is typically integrated into various clothes fashions: to decorate collars, sleeves, hems and hats (see, for example the shtreimel). The so-called Kolinsky sable-hair brushes used for watercolor or oil painting are not manufactured from sable hair, but from that of the siberian weasel.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Harrison, D. J. (editor) (2004). Martens and Fishers (Martes) in Human-Altered Environments: An International Perspective. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0387225803.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ognev, S. (1962). Mammals of Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. Jerusalem: Israel Program for Scientific Translations.

- ↑ Nowak first = R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World, 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1936 pp.. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- ↑ “sable, n., etymology of” The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. http://dictionary.oed.com/. Accessed: 11-2-2008

- ↑ (1990) Grizimek's Encyclopedia of Mammals Volume 3. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Tyler, P. E., "Behind the $100,000 Sable Coat, a Siberian Hunter", The New York Times, 2000-12-27.

- ↑ Martes zibellina – Lower Risk Least Concern. IUCN listing online. Accessed 11-2-2008]

- Bates, J. 2002. Martes zibellina. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved June 07, 2008.

External links

{{credit|Sable|215337983}]