Primate

| Primates | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Olive Baboon | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Families | ||||||||||||||

|

A primate (L. prima, first) is any member of the biological Primates, the group that contains all the species commonly related to the lemurs, monkeys, and apes, with the latter category including humans.

The Primates order is divided informally into three main groupings: prosimians, monkeys of the New World, and monkeys and apes of the Old World. The prosimians are species whose bodies most closely resemble that of the early proto-primates. The most well known of the prosimians, the lemurs, are located on the island of Madagascar and to a lesser extent on the Comoros Islands, isolated from the rest of the world. The New World monkeys include the familiar capuchin, howler, and squirrel monkeys. They live exclusively in the Americas. Discounting humans, the rest of the simians (monkeys and apes), the Old World monkeys and the apes, inhabit Africa and southern and central Asia, although fossil evidence shows many species existed in Europe as well.

Primates are found all over the world. Non-human primates occur mostly in Central and South America, Africa, and southern Asia. A few species exist as far north in the Americas as southern Mexico, and as far north in Asia as northern Japan.

The English singular primate is a back-formation from the Latin name Primates, which itself was the plural of the Latin primas ("one of the first, excellent, noble").

Physical description

All primates have five fingers (pentadactyly), a generalized dental pattern, and a primitive (unspecialized) body plan. Another distinguishing feature of primates is fingernails. Opposing thumbs are also a characteristic primate feature, but are not limited to this order; opossums, for example, also have opposing thumbs. In primates, the combination of opposing thumbs, short fingernails (rather than claws), and long, inward-closingfingers is considered a relic of the ancestral practice of brachiating through trees. Forward-facing color binocular vision was also useful for the brachiating ancestors, particularly for finding and collecting food, although recent studies suggest it was more useful in courtship. All primates, even those that lack the features typical of other primates (like lorises), share eye orbit characteristics, such as a postorbital bar, that distinguish them from other taxonomic orders.

Old World species tend to have significant sexual dimorphism. This is characterized most in size difference, with males being up to a bit more than twice as heavy as females. New World species generally form pair bonds and these species (including tamarins and marmosets) generally do not show a significant size difference between the sexes.

Habitat

Many modern species of primates live mostly in trees and hardly ever come to the ground. Other species are partially terrestrial, such as baboons and the Patas Monkey. Only a few species are fully terrestrial, such as the Gelada and Gorilla.

Primates live in a diverse number of forested habitats, including rainforests, mangrove forests, and mountain forests to altitudes of over 3000 m. Although most species are generally shy of water, a few are fine swimmers and are comfortable in swamps and watery areas, including the Proboscis Monkey, De Brazza's Monkey, and Allen's Swamp Monkey, which even has small webbing between its fingers. Some primates, such the Rhesus Macaque and the Hanuman Langur, are hemerophile species and cities and villages have become their typical habitat.[1]

As the table below illustrates, in many primate species, the males are larger than the females. However this picture is incomplete. All but one of these are Old World species, and in this group the mating system is usually polygynous; sexual dimorphism is expected with this kind of social structure. As the table shows, sexual dimorphism is much less in the marmosets (New World) than in the other species listed, and this is characteristic of marmosets and tamarins in comparison with the Old World monkeys and apes. This is because marmosets and tamarins generally form pair bonds.

| Species | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| Gorilla | 105 kg (231 lb) | 205 kg (452 lb) |

| Human | 62.5 kg (137.5 lb) | 78.4 kg (172 lb) |

| Patas Monkey | 5.5 kg (12 lb) | 10 kg (22 lb) |

| Proboscis Monkey | 9 kg (20 lb) | 19 kg (42 lb) |

| Pygmy Marmoset | 120 g (4.2 oz) | 140 g (5 oz) |

Prosimians

Prosimians are generally considered the most primitive extant primates, representing forms that were ancestral to monkeys and apes. With the exception of the tarsiers, all of the prosimians are in the suborder Strepsirrhini. These include the lemurs, Aye-aye, and lorises. The tasiers are placed in the suborder Haplorrhini (with the monkeys and apes). Due to this reason the classification is not considered valid in terms of phylogeny, as they do not share a unique last common ancestor, and anatomical traits.

New World monkeys

The New World monkeys are the four families of primates that are found in Central and South America: the Cebidae (marmosets, tamarins, capuchins, and squirrel monkeys), Aotidae (night or owl monkeys), Pitheciidae (titis, sakis, and uakaris), and Atelidae (howler, spider, and woolly monkeys). The four families are ranked together as the Platyrrhini parvorder, placing them in a different grouping from the Old World monkeys and the apes.

All New World monkeys differ slightly from Old World monkeys in many aspects, but the most prominent of which is the nose. This is the feature used most commonly to distinguish between the two groups. The scientific name for New world monkey, Platyrrhini, means "flat nosed," therefore the noses are flatter, with side facing nostrils, compared to the narrow noses of the Old World monkey. Most New world monkeys have long, often prehensile tails. Many are small, arboreal, and nocturnal, so our knowledge of them is less comprehensive than that of the more easily observed Old World monkeys. Unlike most Old World monkeys, many New World monkeys form monogamous pair bonds, and show substantial paternal care of young.

Old World monkeys and apes

Old World monkeys

The Old World monkeys or Cercopithecidae are a group of primates placed in the superfamily Cercopithecoidea in the clade Catarrhini. From the point of view of superficial appearance, they are unlike apes in that most have tails (the family name means "tailed ape"), and unlike the New World monkeys in that their tails are never prehensile (adapted to be able to grasp and hold objects). Technically, the distinction of catarrhines from platyrrhines (New World monkeys) depends on the structure of the nose, and the distinction of Old World monkeys from apes depends on dentition.

Several Old World monkeys have anatomical oddities. The colobus monkeys have a stub for a thumb; the Proboscis Monkey has an extraordinary nose while the snub-nosed monkeys have almost no nose at all; the penis of the male Mandrill is colored red and the scrotum has a lilac color, while the face also has bright coloration like the genitalia and this develops in only the dominant male of a multi-male group.

The Old World monkeys are native to Africa and Asia today, but are also known from Europe in the fossil record. They include many of the most familiar species of non-human primates.

Two subfamilies are recognised, the Cercopithecinae, which are mainly African but include the diverse genus of macaques, which are Asian and North African, and the Colobinae, which includes most of the Asian genera but also the African colobus monkeys.

Apes

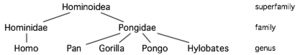

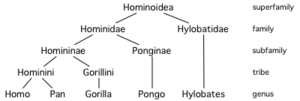

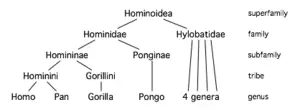

Apes are the members of the Hominoidea superfamily of primates, which includes humans. Under current classification, there are two families of hominoids:

- the family Hylobatidae consists of 4 genera and 12 species of gibbons, including the Lar Gibbon and the Siamang, collectively known as the "lesser apes"

- the family Hominidae consisting of gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, and humans, collectively known as the "great apes".

A few other primates have the word "ape" in their common names, but they are not regarded as true apes.

Except for gorillas and humans, all true apes are agile climbers of trees. They are best described as omnivorous, their diet consisting of fruit, grass seeds, and in most cases some quantities of meat and invertebrates—either hunted or scavenged—along with anything else available and easily digested. They are native to Africa and Asia, although humans have spread to all parts of the world.

Most ape species are rare or endangered. The chief threat to most of the endangered species is loss of tropical rainforest habitat, though some populations are further imperiled by hunting for bushmeat.

Historical and modern terminology

"Ape" (Old Eng. apa; Dutch aap; Old Ger. affo; Welsh epa; Old Czech op) is a word of uncertain origin and is possibly an onomatopoetic imitation of animal chatter. The term has a history of rather imprecise usage. Its earliest meaning was a tailless (and therefore exceptionally human-like) non-human primate, but as zoological knowledge developed it became clear that taillessness occurred in a number of different and otherwise unrelated species.

The original usage of "ape" in English may have referred to the baboon, an African monkey. Two tailless species of macaque are commonly named as apes, the Barbary Ape of North Africa (introduced into Gibraltar), Macaca sylvanus, and the Sulawesi Black Ape or Celebes Crested Macaque, M. nigra.

Until a handful of decades ago, humans were thought to be distinctly set apart from the other apes (even from the other great apes), so much so that many people still don't think of the term "apes" to include humans at all. However, it is not considered accurate by many biologists to think of apes in a biological sense without considering humans to be included. The terms "non-human apes" or "non-human great apes" is used with increasing frequency to show the relationship of humans to the other apes while yet talking only about the non-human species.

A group of apes may be referred to as a troop or a shrewdness.

Biology

The gibbon family, Hylobatidae, is composed of thirteen medium-sized species. Their major distinction are their long arms which they use to brachiate through the trees. As an evolutionary adaption to this arboreal lifestyle, their wrists are ball and socket joints. The largest of the gibbons, the Siamang, weighs up to 23 kg (50 lb). In comparison, the smallest great ape is the Common Chimpanzee at a modest 40 to 65 kg (88 to 143 lb).

The great ape family was previously referred to as Pongidae, and humans (and fossil hominids) were omitted from it, but on grounds of relatedness there is no argument for doing this. Chimpanzees, gorillas, humans and orangutans are all more closely related to one another than any of these four genera are to the gibbons. Awkwardly, however, the term "hominid" is still used with the specific meaning of extinct animals more closely related to humans than the other great apes (for example, australopithecines). It is now usual to use even finer divisions, such as subfamilies and tribes to distinguish which hominoids are being discussed. Current evidence implies that humans share a common, extinct, ancestor with the chimpanzee line, from which we separated more recently than the gorilla line.

Both great apes and lesser apes fall within Catarrhini, which also includes the Old World monkeys of Africa and Eurasia. Within this group, both families of apes can be distinguished from these monkeys by the number of cusps on their molars (apes have five—the "Y-5" molar pattern, Old World monkeys have only four in a "bilophodont" pattern). Apes have more mobile shoulder joints and arms, ribcages that are flatter front-to-back, and a shorter, less mobile spine compared to Old World monkeys. These are all anatomical adaptations to vertical hanging and swinging locomotion (brachiation) in the apes. All living members of the Hylobatidae and Hominidae are tailless, and humans can therefore accurately be referred to as bipedal apes. However there are also primates in other families that lack tails, and at least one (the Pig-Tailed Langur) that has been known to walk significant distances bipedally.

Although the hominoid fossil record is far from complete, and the evidence is often fragmentary, there is enough to give a good outline of the evolutionary history of humans. The time of the split between humans and living apes used to be thought to have occurred 15 to 20 million years ago, or even up to 30 or 40 million years ago. Some apes occurring within that time period, such as Ramapithecus, used to be considered as hominins, and possible ancestors of humans. Later fossil finds indicated that Ramapithecus was more closely related to the orangutan, and new biochemical evidence indicated that the last common ancestor of humans and other hominins occurred between 5 and 10 million years ago, and probably in the lower end of that range.

Cultural aspects of non-human apes

The intelligence and humanoid appearance of non-human apes are responsible for legends which attribute human qualities; for example, they are sometimes said to be able to speak but refuse to do so in order to avoid work. They are also said to be the result of a curse—a Jewish folktale claims that one of the races who built the Tower of Babel became non-human apes as punishment, while Muslim lore says that the Jews of Elath became non-human apes as punishment for fishing on the Sabbath. Christian folklore claims that non-human apes are a symbol of lust and were created by Satan in response to God's creation of humans. It is uncertain whether any of these references is to any specific non-human apes, since all date from a period when the distinction between non-human apes and monkeys was not widely understood, or not understood at all.

Humans and the other apes share many similarities, including the ability to properly use tools and imitate others. Recent studies at Yale test some of these similarities. A professor and his/her students gave a challenge to baby humans and baby chimps. Both groups were shown a way that might solve the challenge. However what both the baby humans and chimps did not know was that the way that was shown was incorrect. Both times the baby humans tried they imitated what they were shown and failed at the attempt. For the chimps, the first time they tried, they followed the same path and failed. However on a second time around they succeeded in finding a new path and actually completed the objective. The professor interpreted that baby chimps learned from experience while baby humans just imitated what they were shown. This gave scientists key information in understanding the cultural aspects of ape life and evolutionary similarities between humans and apes.

There have also been recent breakthroughs in evidence of ape culture that go beyond what was explained above. This was further explored by scientists at the convention in St. Louis.[2]

New subspecies?

In 2002, a new giant ape troop was discovered in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These apes share many features of both chimpanzees and gorillas. According to a report from BBC News Online,[3], the apes have large black faces, are two meters (6.6 feet) tall and make nests on the ground, all like gorillas. However, they live hundreds of kilometers from any other gorilla troops, and their diet is high in fruits, similar to the chimpanzee diet and are said by the locals to be active hunters, even overpowering local lions. They were given the common name of Bili Ape.

Subsequent molecular investigation of pelt samples showed them to be Common Chimpanzees who had individually adapted to local conditions. This would indicate that they may be a subspecies of the common chimp, although this only definitively points to a chimp maternal ancestor, as mtDNA (mitochondreal DNA) is transferred from mother to child. This analysis would not rule out the possibility of a gorilla/chimp hybrid where the ancestral father is a gorilla.

History of hominoid taxonomy

The history of hominoid taxonomy is somewhat confusing and complex. The names of subgroups have changed their meaning over time as new evidence from fossil discoveries, anatomy comparisons and DNA sequences, has changed understanding of the relationships between hominoids. The story of the hominoid taxonomy is one of gradual demotion of humans from a special position in the taxonomy to being one branch among many. It also illustrates the growing influence of cladistics (the science of classifying living things by strict descent) on taxonomy.

As of 2006, there are eight extant genera of hominoids. They are the four great ape genera (Homo (humans), Pan (chimpanzees), Gorilla, and Pongo (orangutans)), and the four genera of gibbons (Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus, and Symphalangus).[4] (The genus for the hoolock gibbons was recently changed from Bunopithecus to Hoolock.[5])

In 1758, Carolus Linnaeus, relying on second- or third-hand accounts, placed a second species in Homo along with H. sapiens: Homo troglodytes ("cave-dwelling man"). It is not clear to which animal this name refers, as Linnaeus had no specimen to refer to, hence no precise description. Linnaeus named the orangutan Simia satyrus ("satyr monkey"). He placed the three genera Homo, Simia and Lemur in the family of Primates.

The troglodytes name was used for the chimpanzee by Blumenbach in 1775 but moved to the genus Simia. The orangutan was moved to the genus Pongo in 1799 by Lacépède.

Linnaeus's inclusion of humans in the primates with monkeys and apes was troubling for people who denied a close relationship between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom. Linneaus's Lutheran Archbishop had accused him of "impiety." In a letter to Johann Georg Gmelin dated February 25, 1747, Linnaeus wrote:

- It is not pleasing to me that I must place humans among the primates, but man is intimately familiar with himself. Let's not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name is applied. But I desperately seek from you and from the whole world a general difference between men and simians from the principles of Natural History. I certainly know of none. If only someone might tell me one! If I called man a simian or vice versa I would bring together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to, in accordance with the law of Natural History.[6]

Accordingly, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the first edition of his Manual of Natural History (1779), proposed that the primates be divided into the Quadrumana (four-handed, i.e. apes and monkeys) and Bimana (two-handed, ie. humans). This distinction was taken up by other naturalists, most notably Georges Cuvier. Some elevated the distinction to the level of order.

However, the many affinities between humans and other primates — and especially the great apes — made it clear that the distinction made no scientific sense. Charles Darwin wrote, in The Descent of Man:

- The greater number of naturalists who have taken into consideration the whole structure of man, including his mental faculties, have followed Blumenbach and Cuvier, and have placed man in a separate Order, under the title of the Bimana, and therefore on an equality with the orders of the Quadrumana, Carnivora, etc. Recently many of our best naturalists have recurred to the view first propounded by Linnaeus, so remarkable for his sagacity, and have placed man in the same Order with the Quadrumana, under the title of the Primates. The justice of this conclusion will be admitted: for in the first place, we must bear in mind the comparative insignificance for classification of the great development of the brain in man, and that the strongly-marked differences between the skulls of man and the Quadrumana (lately insisted upon by Bischoff, Aeby, and others) apparently follow from their differently developed brains. In the second place, we must remember that nearly all the other and more important differences between man and the Quadrumana are manifestly adaptive in their nature, and relate chiefly to the erect position of man; such as the structure of his hand, foot, and pelvis, the curvature of his spine, and the position of his head.[7]

Until about 1960, the hominoids were usually divided into two families: humans and their extinct relatives in Hominidae, the other apes in Pongidae.[8]

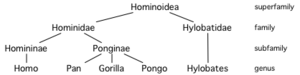

The 1960s saw the application of techniques from molecular biology to primate taxonomy. Goodman used his 1963 immunological study of serum proteins to propose a division of the hominoids into three families, with the non-human great apes in Pongidae and the lesser apes (gibbons) in Hylobatidae.[9] The trichotomy of hominoid families, however, prompted scientists to ask which family speciated first from the common hominoid ancestor.

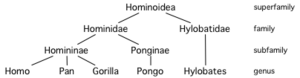

Within the superfamily Hominoidea, gibbons are the outgroup: this means that the rest of the hominoids are more closely related to each other than any of them are to gibbons. This led to the placing of the other great apes into the family Hominidae along with humans, by demoting the Pongidae to a subfamily; the Hominidae family now contained the subfamilies Homininae and Ponginae. Again, the three-way split in Ponginae led scientists to ask which of the three genera is least related to the others.

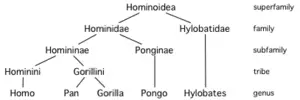

Investigation showed orangutans to be the outgroup, but comparing humans to all three other hominid genera showed that African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas) and humans are more closely related to each other than any of them are to orangutans. This led to the placing of the African apes in the subfamily Homininae, forming another three-way split. This classification was first proposed by M. Goodman in 1974.[10]

To try to resolve the hominine trichotomy, some authors proposed the division of the subfamily Homininae into the tribes Gorillini (African apes) and Hominini (humans).

However, DNA comparisons provide convincing evidence that within the subfamily Homininae, gorillas are the outgroup. This suggests that chimpanzees should be in Hominini along with humans. This classification was first proposed (though one rank lower) by M. Goodman et. al. in 1990.[11] See Human evolutionary genetics for more information on the speciation of humans and great apes.

Later DNA comparisons split the gibbon genus Hylobates into four genera: Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus, and Symphalangus.[4][5]

Classification and evolution

As discussed above, hominoid taxonomy has undergone several changes. Current understanding is that the apes diverged from the Old World monkeys about 25 million years ago. The lesser and greater apes split about 18 mya, and the hominid splits happen 14 mya (Pongo), 7 mya (Gorilla), and 3-5 mya (Homo & Pan)

- Superfamily Hominoidea[4]

Legal status

Humans are the only apes recognized as persons and protected in law by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights[12] and by all governments, though to varying degrees. The non-human apes are not classified as persons, which means that where their interests intersect with that of humans they have no legal status.

Many argue that the other apes' cognitive capacity in itself, as well as their close genetic relationship to human beings, dictates an acknowledgement of personhood. The Great Ape Project, founded by Australian philosopher Peter Singer, is campaigning to have the United Nations endorse its Declaration on Great Apes, which would extend to all species of chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans the protection of three basic interests: the right to life, the protection of individual liberty, and the prohibition of torture.

See also

- List of fictional apes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primaten

- ↑ Corey Binns (2006-02-28). Case Closed: Apes Got Culture. Livescience.com.

- ↑ 'New' giant ape found in DR Congo. BBC News Online (2004-10-10).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMSW3 - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mootnick, A. and Groves, C. P. (2005). A new generic name for the hoolock gibbon (Hylobatidae). International Journal of Primatology (26): 971-976.

- ↑ Letter, Carl Linnaeus to Johann Georg Gmelin. Uppsala, Sweden, 25 February 1747. Swedish Linnaean Society.

- ↑ Charles Darwin (1871). The Descent of Man.

- ↑ G. G. Simpson (1945). The principles of classification and a classification of mammals. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 85: 1–350.

- ↑ M. Goodman (1963). "Man’s place in the phylogeny of the primates as reflected in serum proteins", in S. L. Washburn: Classification and human evolution. Aldine, Chicago, 204–234.

- ↑ M. Goodman (1974). Biochemical Evidence on Hominid Phylogeny. Annual Review of Anthropology 3: 203–228.

- ↑ M. Goodman, D. A. Tagle, D. H. Fitch, W. Bailey, J. Czelusniak, B. F. Koop, P. Benson, J. L. Slightom (1990). Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids. Journal of Molecular Evolution 30: 260–266.

- ↑ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations (1948-12-10).

Classification and evolution

Close relations

The Primate order lies in a tight clustering of related orders (the Euarchontoglires) within the Eutheria, a subclass of Mammalia. Recent molecular genetic research on primates, flying lemurs, and treeshrews has shown that the two species of flying lemur (Dermoptera) are more closely related to the primates than the treeshrews of the order Scandentia, even though the treeshrews were at one time considered primates. These three orders make up the Euarchonta clade. This clade combines with the Glires clade (made up of the Rodentia and Lagomorpha) to form the Euarchontoglires clade. Variously, both Euarchonta and Euarchontoglires are ranked as superorders. Also, some scientists consider Dermoptera a suborder of Primates and call the "true" primates the suborder Euprimates.Template:Cite needed

Euarchontoglires

├─Glires

│ ├─rodents (Rodentia)

│ └─rabbits, hares, pikas (Lagomorpha)

└─Euarchonta

├─treeshrews (Scandentia)

└─N.N.

├─flying lemurs (Dermoptera)

└─N.N.

├─Plesiadapiformes (extinct)

└─primates (Primates)

Classification

In older classifications, the Primates were divided into two superfamilies: Prosimii and Anthropoidea. The Prosimii included all of the prosimians: all of Strepsirrhini plus the tarsiers. The Anthropoidea contained all of the simians.

In modern, cladistic reckonings, the Primate order is also a true clade. The suborder Strepsirrhini, the "wet-nosed" primates, split off from the primitive primate line about 63 million years ago (mya). The seven strepsirhine families are the four related lemur families and the three remaining families that include the lorises, the Aye-aye, the galagos, and the pottos.[1] Some classification schemes wrap the Lepilemuridae into the Lemuridae and the Galagidae into the Lorisidae, yielding a three-two family split instead of the four-three split as presented here.[1] Other lineages of lower primates inhabited Earth. During the Eocene, most of the northern continents were dominated by two dominant groups, the adapids and the omomyids. The former is considered a member of Strepsirrhini, but it does not have a tooth-comb like modern lemurs. The latter was related closely to tarsiers, monkeys, and apes. Adapids survived until 10 mya; omomyids on the other hand perished 20 million years earlier.

The Aye-aye is difficult to place in Strepsirrhini.[1] Its family, Daubentoniidae, could be a lemuriform primate and its ancestors split from lemur line more recently than the lemurs and lorises split, about 50 mya. Otherwise it is sister to all of the other strepsirrhines, in which case in evolved away from the main strepsirrhine line between 50 and 63 mya.

The suborder Haplorrhini, the "dry-nosed" primates, is composed of two sister clades.[1] The prosimian tarsiers in family Tarsiidae (monotypic in its own infraorder Tarsiiformes), represent the most primitive division at about 58 mya. The Simiiformes infraorder contains the two parvorders: the New World monkeys in one, and the Old World monkeys, humans and the other apes in the other.[1] This division happened about 40 mya. However about 30 mya, three groups split from the main haplorrhine lineage. One group stayed in Asia and are closest in kin to the "dawn monkey" Eosimias. The second stayed in Africa, where they developed into the Old World primates. The third rafted to South America to become the New World monkeys. Mysteriously the aboriginal Asian Haplorrhini vanished from record once Africa collided with Eurasia 24 mya. Apes and monkeys spread into Europe and Asia. Close behind came lorises and tarsiers, also African castaways. The first hominid fossils were discovered in Northern Africa and date back 7 mya. Modern humans did not appear until 0.2 mya, eventually becoming the most prevalent primate and mammal on Earth.

The discovery of new species happens at a rate of a few new species each year, and the evaluation of current populations as distinct species is in flux. Colin Groves lists about 350 species of primates in Primate Taxonomy in 2001.[2] The recently published third edition of Mammal Species of the World (2005) lists 376 species.[1] But even MSW3's list falls short of current understanding as its collection cutoff was in 2003. Notable new species not listed in MSW3 include Cleese's Woolly Lemur (named after British actor and lemur enthusiast John Cleese) and the GoldenPalace.com Monkey (whose name was put up for auction).

Extant primate families

- ORDER PRIMATES

- Suborder Strepsirrhini: non-tarsier prosimians

- Infraorder Lemuriformes

- Superfamily Cheirogaleoidea

- Family Cheirogaleidae: dwarf lemurs and mouse-lemurs (24 species)

- Superfamily Lemuroidea

- Family Lemuridae: lemurs (19 species)

- Family Lepilemuridae: sportive lemurs (11 species)

- Family Indriidae: woolly lemurs and allies (12 species)

- Superfamily Cheirogaleoidea

- Infraorder Chiromyiformes

- Family Daubentoniidae: Aye-aye (1 species)

- Infraorder Lorisiformes

- Family Lorisidae: lorises, pottos and allies (9 species)

- Family Galagidae: galagos (19 species)

- Infraorder Lemuriformes

- Suborder Haplorrhini: tarsiers, monkeys and apes

- Infraorder Tarsiiformes

- Family Tarsiidae: tarsiers (7 species)

- Infraorder Simiiformes

- Parvorder Platyrrhini: New World monkeys

- Family Cebidae: marmosets, tamarins, capuchins and squirrel monkeys (56 species)

- Family Aotidae: night or owl monkeys (douroucoulis) (8 species)

- Family Pitheciidae: titis, sakis and uakaris (41 species)

- Family Atelidae: howler, spider and woolly monkeys (24 species)

- Parvorder Catarrhini

- Superfamily Cercopithecoidea

- Family Cercopithecidae: Old World monkeys (135 species)

- Subfamily Cercopithecinae

- Tribe Cercopithecini (Allen's Swamp Monkey, talapoins, Patas Monkey, Silver Monkey, Guenons, Owl-faced Monkey, etc.)

- Tribe Papionini (Macaques, mangabeys, Gelada, Hamadryas Baboon, Olive Baboon, Yellow Baboon, mandrills, etc.)

- Subfamily Colobinae

- African group (colobuses)

- Langur (leaf monkey) group (langurs, leaf monkeys, surilis)

- Odd-Nosed group (doucs, snub-nosed monkeys, Proboscis Monkey, Pig-tailed Langur)

- Subfamily Cercopithecinae

- Family Cercopithecidae: Old World monkeys (135 species)

- Superfamily Hominoidea

- Family Hylobatidae: gibbons or "lesser apes" (13 species)

- Family Hominidae: humans and other great apes (7 species)

- Superfamily Cercopithecoidea

- Parvorder Platyrrhini: New World monkeys

- Infraorder Tarsiiformes

- Suborder Strepsirrhini: non-tarsier prosimians

Some prehistoric primates

- Adapis, an adapid

- Australopithecus, a human-like animal

- Branisella boliviana, an early New World monkey

- Dryopithecus, an early ape

- Eosimias, an early catarrhine

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis, a possible ancestor of humans

- Aegyptopithecus zeuxis, an early haplorrhine

- Pliopithecus, ancestor of the modern gibbons

- Gigantopithecus, the largest ape

- Godinotia, an adapid

- Megaladapis, a giant lemur

- Notharctus, an adapid

- Plesiopithecus teras, a relative of lorises and galagos

- Protopithecus brasiliensis, a giant New World monkey

- Sivapithecus, an early ape

- Tielhardina, the earliest haplorrhines

- Victoriapithecus, an early Old World monkey

- Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, a possible ancestor of large apes

Primate hybrids

In "The Variation Of Animals And Plants Under Domestication" Charles Darwin noted: "Several members of the family of Lemurs have produced hybrids in the Zoological Gardens."

Many gibbons are hard to identify based on fur coloration and are identified either by song or genetics. These morphological ambiguities have led to hybrids in zoos. Zoo gibbons usually come from the black market pet trade in Southeast Asia, which transported gibbons across countries all over the region. As a result, perhaps as much as 95% of zoo gibbons are of unknown geographic origin. As most zoos rely on morphological variation or labels that are impossible to verify to assign species and subspecies names, it is unfortunately common for gibbons to be misidentified and housed together. For example, some collections' supposedly pure breeding pairs were actually mixed pairs or hybrids from previous mixed pairs. The hybrid offspring were sent to other gibbon breeders and led to further hybridization in captive gibbons. Within-genus hybrids also occur in wild gibbons where the ranges overlap (Agile Gibbons and Pileated Gibbons x Lar Gibbons, Agile Gibbons x Müller's Bornean Gibbon, Yellow-cheeked Gibbons x Northern White-cheeked Gibbons).

Intergeneric gibbon hybridizations have only occurred in captivity. Silvery Gibbons (Hylobates moloch) and Müller's Bornean Gibbon (H. muelleri) have hybridized with Siamangs (Symphalangus syndactylus) in captivity - a female Siamang produced hybrid "Siabon" offspring on 2 occasions when housed with a male gibbon; only one hybrid survived.

Anubis Baboons and Hamadryas Baboons have hybridized in the wild where their ranges meet. A Rheboon is a captive-bred Rhesus Macaque/Hamadryas Baboon hybrid with a baboon-like body shape and macaque-like tail.

Different macaque species can interbreed. In "The Variation Of Animals And Plants Under Domestication" Charles Darwin wrote: A Macacus, according to Flourens, bred in Paris; and more than one species of this genus has produced young in London, especially the Macacus rhesus, which everywhere shows a special capacity to breed under confinement. Hybrids have been produced both in Paris and London from this same genus. The Japanese Macaque (Macaca fuscata) has interbred with the introduced Taiwanese Macacque (M. cyclopis) when the latter escaped into the wild from private zoos.

Various hybrid monkeys are bred within the pet trade, for example:

- Hybrid capuchin monkeys e.g. Tufted Capuchin (Cebus apella) x Weeper Capuchin (C. olivaceus)

- Liontail Macaque x Pigtail Macaque hybrids

- Rhesus Macaque x Stumptail Macaque hybrids.

Among Old World monkeys, natural hybridization is not uncommon. There numerous field reports of hybrid monkeys and detailed studies of zones where species overlap and hybrids occur.

Among the great apes, Sumatran and Bornean orangutans are considered separate species with anatomical differences, producing sterile or poorly fertile hybrids. Hybrid orangutans are genetically weaker, with lower survival rates than pure animals.

Legal status

Humans are recognized as persons and protected in law by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights[3] and by all governments, though to varying degrees. Non-human primates are not classified as persons, which means their individual interests have no formal recognition or protection. The status of non-human primates has generated much debate, particularly through the Great Ape Project[4] which argues for their personhood.

Thousands of primates are used every year around the world in scientific experiments because of their psychological and physiological similarity to humans. The species most commonly used are chimpanzees, baboons, marmosets, macaques, and African green monkeys. In the European Union, around 10,000 were used in 2004, with 4,652 experiments conducted on 3,115 non-human primates in the UK alone in 2005.[5] As of 2004, 3,100 non-human great apes were living in captivity in the United States, in zoos, circuses, and laboratories, 1,280 of them being used in experiments.[4] European campaign groups such as the BUAV are seeking a ban on all primate use in experiments as part of the European Union's current review of existing law on animal experimentation.

See also

- Arboreal theory

- Primatology

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 C. Groves, "Order Primates," "Order Monotremata," (and select other orders). Page(s) 111-184 in D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder, eds., Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition, Johns Hopkins University Press (2005). ISBN 0801882214.

- ↑ Primate Taxonomy (Smithsonian Institute Press, 2001), Colin Groves (ISBN 1-56098-872-X )

- ↑ UN Declaration of Human Rights

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Declaration on Great Apes, Great Ape Project

- ↑ British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection - Primates

- ^ Primates in Question (Smithsonian Institute Press, 2003), Robert W. Shumaker & Benjamin B. Beck (ISBN 1-58834-176-3 )

External links

- High-Resolution Cytoarchitectural Primate Brain Atlases

- Primate Info Net

- Primates in scientific experimentation

- Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.