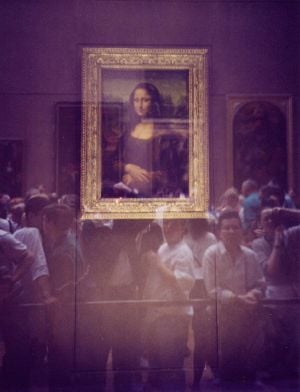

Mona Lisa

|

| Mona Lisa La Gioconda |

| Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1503–1507 |

| Oil on poplar |

| 77 × 53 cm, 30 × 21 in |

| Musée du Louvre, Paris |

Mona Lisa, or La Gioconda (La Joconde), is a 16th century oil painting on a poplar panel by Leonardo Da Vinci. It is arguably the most famous painting in the world, and few other works of art have been subject to as much scrutiny, study, mythologizing and parody. It is owned by the French government and hangs in the Musée du Louvre in Paris. The painting, a half-length portrait, depicts a woman whose gaze meets the viewer's with an expression often described as enigmatic. [1] [2] It is considered by many to be Leonardo's magnum opus.

Naming the Mona Lisa

The title Mona Lisa stems from the Giorgio Vasari biography of Leonardo da Vinci, published 31 years after Leonardo's death. In it, he identified the sitter as Lisa Gherardini, the wife of wealthy Florentine businessman Francesco del Giocondo. Mona was a common Italian contraction of madonna, meaning my lady, the equivalent of the English Madam, so the title means Madam Lisa.

In modern Italian, the short form of madonna is usually spelled Monna, so the title is sometimes given as Monna Lisa. This is rare in English, but more common in Romance languages such as French and Italian.

The alternative title, La Gioconda, is the feminine form of Giocondo. In Italian, giocondo also means light-hearted (jocund in English), so gioconda means light-hearted woman. Because of her smile, this version of the title plays on this double meaning, as does the French La Joconde.

Both Mona Lisa and La Gioconda became established as titles for this painting in the 19th century. Before these names became established, the painting had been referred to by various descriptive phrases, such as "a certain Florentine lady" and "a courtesan in a gauze veil".

History

16th century

Leonardo da Vinci began painting the Mona Lisa in 1502 (during the Italian Renaissance) and, according to Vasari, completed it in four years.

Leonardo took the painting from Italy to France in 1516 when King François I invited the painter to work at the Clos Lucé near the king's castle in Amboise. The King bought the painting for 4,000 écus and kept it at Fontainebleau, where it remained until moved by Louis XIV.

It has for a long time been argued that after Leonardo's death the painting was cut down by having part of the panel at both sides removed. Early copies depict columns on both sides of the figure. Only the edges of the bases can be seen in the original.[3] However, some art historians, such as Martin Kemp, now argue that the painting has not been altered, and that the columns depicted in the copies were added by the copyists. The latter view was bolstered during 2004 and 2005 when an international team of 39 specialists undertook the most thorough scientific examination of the Mona Lisa yet undertaken. Beneath the frame (the current one was fitted to the Mona Lisa in 2004) there was discovered a "reserve" around all four edges of the panel. A reserve is an area of bare wood surrounding the gessoed and painted portion of the panel. That this is a genuine reserve, and not the result of removal of the gesso or paint is demonstrated by a raised edge still existing around the gesso, the result of build up from the edge of brush strokes at the edge of the gesso area.

The reserve area, which was likely to have been as much as 20 mm originally appears to have been trimmed at some point probably to fit a frame (we know that in the 1906 framing it was the frame itself which was trimmed, not the picture, so it must have been earlier), however at no point has any of Leonardo's actual paint been trimmed. Therefore the columns in early copies must be inventions of those artists, or copies of another (unknown) studio version of Mona Lisa. The round objects each side of the sill remain as mysterious as so much of this painting.

Other versions

It has been suggested that Leonardo created more than one version of the painting. The owners of the version known as the Isleworth Mona Lisa claim that it is an original, though the great majority of art historians reject its authenticity. The same claim has been made for a version in the Vernon collection.[4] Another version, dating from c.1616 was given in c.1790 to Joshua Reynolds by the Duke of Leeds in exchange for a Reynolds self-portrait. Reynolds thought it to be the real painting and the French one a copy, which has now been disproved. It is, however, useful in that it was copied when the original's colors were far brighter than they are now, and so it gives some sense of the original's appearance 'as new'. It is held in the stores of the Dulwich Picture Gallery.[5] There are also copies of the image in which the figure appears nude. These have also led to speculation that they were copied from a lost Leonardo original depicting Lisa naked.[6]

17th to 19th century

Louis XIV moved the painting to the Palace of Versailles. After the French Revolution, it was moved to the Louvre. Napoleon I had it moved to his bedroom in the Tuileries Palace; later it was returned to the Louvre. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, it was moved from the Louvre to a hiding place elsewhere in France.

The painting was not well-known until the mid-19th century, when artists of the emerging Symbolist movement began to appreciate it, and associated it with their ideas about feminine mystique. Critic Walter Pater, in his 1867 essay on Leonardo, expressed this view by describing the figure in the painting as a kind of mythic embodiment of eternal femininity, who is "older than the rocks among which she sits" and who "has been dead many times and learned the secrets of the grave."

20th century to present

Theft

The painting's increasing fame was further emphasized when it was stolen on August 21, 1911. The next day, Louis Béroud, a painter, walked into the Louvre and went to the Salon Carré where the Mona Lisa had been on display for five years. However, where the Mona Lisa should have stood, he found four iron pegs.

Béroud contacted the section head of the guards, who thought the painting was being photographed for marketing purposes. A few hours later, Béroud checked back with the section head of the museum, and it was confirmed that the Mona Lisa was not with the photographers. The Louvre was closed for an entire week to aid in investigation of the theft.

French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had once called for the Louvre to be "burnt down," came under suspicion; he was arrested and put in jail. Apollinaire pointed to his friend Pablo Picasso, who was also brought in for questioning, but both were later exonerated.[7]

At the time, the painting was believed to be lost forever, and it would be two years before the real thief was discovered. Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia stole it by entering the building during regular hours, hiding in a broom closet and walking out with it hidden under his coat after the museum had closed. Peruggia was an Italian patriot who believed da Vinci's painting should be returned to Italy for display in an Italian museum. Peruggia may have also been motivated by a friend who sold copies of the painting, which would skyrocket in value after the theft of the original. After having kept the painting in his apartment for two years, Peruggia grew impatient and was finally caught when he attempted to sell it to the directors of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence; it was exhibited all over Italy and returned to the Louvre in 1913. Peruggia was hailed for his patriotism in Italy and only served a few months in jail for the crime.[7]

Second World War

During World War II, the painting was again removed from the Louvre and taken to safety, first in Château d'Amboise, then in the Loc-Dieu Abbey and finally in the Ingres Museum in Montauban.

Post-war

In 1956, the lower part of the painting was severely damaged when someone doused it with acid. On December 30 of that same year, Ugo Ungaza Villegas, a young Bolivian, damaged the painting by throwing a rock at it. This resulted in the loss of a speck of pigment near the left elbow, which was later painted over. The painting is now covered with bulletproof security glass.

From December 14 1962 to March of 1963, the French government lent it to the United States to be displayed in New York City and Washington D.C. In 1974, the painting exhibited in Tokyo and Moscow before being returned to the Louvre.

Prior to the 1962–1963 tour, the painting was assessed for insurance purposes at $100 million. According to the Guinness Book of Records, this makes the Mona Lisa the most valuable painting ever insured. As an expensive painting, it has only recently been surpassed (in terms of actual dollar price) by three other paintings, the Adele Bloch-Bauer I by Gustav Klimt, which was sold for $135 million (£73 million), the Woman III by Willem de Kooning sold for $137.5 million in November of 2006, and most recently No. 5, 1948 by Jackson Pollock sold for a record $140 million on November 2, 2006. Although these figures are greater than that which the Mona Lisa was insured for, the comparison does not account for the change in prices due to inflation — $100 million in 1962 is approximately $670 million in 2006 when adjusted for inflation using the US Consumer Price Index.[8]

In 2004 experts from the National Research Council of Canada conducted a three-dimensional infrared scan. Because of the aging of the varnish on the painting it has been difficult to discern details. Data from the scan and infrared reflectography were later used by Bruno Mottin of the French Museums' "Center for Research and Restoration" to argue that the transparent gauze veil worn by the sitter is a guarnello, typically used by women while pregnant or just after giving birth. A similar guarnello was painted by Sandro Botticelli in his Portrait of Smeralda Brandini (1470), depicting a pregnant woman (on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London). Furthermore, this reflectography revealed that Mona Lisa's hair is not loosely hanging down, but seems attached at the back of the head to a bonnet or pinned back into a chignon and covered with a veil, bordered with a sombre rolled hem. In the 16th century, hair hanging loosely down on the shoulders was the customary apanage of unmarried young women or prostitutes. This apparent contradiction with her status as a married woman has now been resolved.

Researchers also used the data to reveal details about the technique used and to predict that the painting will degrade very little if current conservation techniques are continued.[9][10][11]

On April 6, 2005 — following a period of curatorial maintenance, recording, and analysis — the painting was moved, within the Louvre, to a new home in the museum's Salle des États. It is displayed in a purpose-built, climate-controlled enclosure behind bullet proof glass.[12] The Mona Lisa has since undergone a major scientific observation, and it has been proved through infrared cameras she is wearing a bonnet and clenching her chair (something that Leonardo decided to change as an afterthought).[13]

Conservation History

The Mona Lisa has survived intact for more than 500 years, and an international commission convened in 1952 noted that "the picture is in a remarkable state of preservation."[14] This is partly due to the result of a variety of conservation treatments the painting has undergone in its history. A detailed analysis of the picture in 1933 by Madame de Gironde revealed that earlier restorers had "acted with a great deal of restraint."[15] Nevertheless, applications of varnish made to the painting had darkened even by the end of the 16th century, and an aggressive 1809 cleaning and re-varnish removed some of the uppermost portion of the paint layer, resulting in a washed-out appearance to the face of the figure. Despite these few unfortunate treatments, the Mona Lisa has been well cared for throughout its history, and the 2004-05 conservation team was optimistic about the future of the work.[16]

Poplar panel

At some point in its history, the Mona Lisa was removed from its original frame. The unconstrained poplar panel was allowed to warp freely with changes in humidity, and as a result, a crack began to develop near the top of the panel. The crack extends down to the hairline of the figure. In the mid 18th to early 19th century, someone attempted to stabilize the crack by inlaying two butterfly shaped walnut braces into the back of the panel to a depth of about 1/3 the thickness of the panel. This work was skillfully executed, and has successfully stabilized the crack. Sometime between 1888 and 1905, or perhaps at some point during the picture's theft, the upper brace fell out. A later restorer glued and lined the resulting socket and crack with cloth. The picture is currently kept under strict, climate controlled conditions in its bullet-proof glass case. The humidity is maintained at 50% ±10%, and the temperature is maintained between 18 and 21°C. To compensate for fluctuations in relative humidity, the case is supplemented with a bed of silica gel treated to provide 55% relative humidity.[17]

Frame

Because the Mona Lisa's poplar support expands and contracts with changes in humidity, the picture has experienced some warping. In response to warping and swelling experienced during its storage during World War II, and to prepare the picture for an exhibit to honor the anniversary of Da Vinci's 500th birthday, the Mona Lisa was fitted in 1951 with a flexible oak frame with beech crosspieces. This flexible frame, which is used in addition to the decorative frame described below, exerts pressure on the panel to keep it from warping further. In 1970, the beech crosspieces were switched to maple after it was found that the beech wood had been infested with insects. In 2004-05, a conservation and study team replaced the maple crosspieces with sycamore ones, and an additional metal crosspiece was added for scientific measurement of the panel's warp. The Mona Lisa has had many different decorative frames in its history, owing to changes in taste over the centuries. In 1906, the picture was given its current frame by the countess of Béarn, a Renaissance frame consistent with the historical period of the Mona Lisa. The edges of the painting have been trimmed at least once in its history to fit the picture into various frames, but none of the original paint layer has been trimmed.[18]

Insect treatment

In 1977, a new insect infestation was discovered in the back of the panel as a result of the beech crosspieces installed to keep the painting from warping. This was treated on the spot with carbon tetrachloride, and later with an ethylene oxide treatment. In 1985, the spot was again treated with carbon tetrachloride as a preventive measure.[19]

Cleaning and Touch-up

The first and most extensive recorded cleaning, revarnishing, and touch up of the Mona Lisa was an 1809 wash and re-varnish undertaken by Jean-Marie Hooghstoel, who was responsible for restoration of paintings for the galleries of the Musée Napoléon. The work involved cleaning with spirits, touch up of color, and revarnishing the painting. In 1906, Louvre restorer Eugène Denizard performed watercolor retouches on areas of the paint layer disturbed by the crack in the panel. Denizard also retouched the edges of the picture with varnish, to mask areas that had been covered initially by an older frame. In 1913, when the painting was recovered after its theft, Denizard was again called upon to work on the Mona Lisa. Denizard was directed to clean the picture without solvent, and to lightly touch up several scratches to the painting with watercolor. In 1952, the varnish layer over the background in the painting was evened out. After the 1956 attack, restorer Jean-Gabriel Goulinat was directed to touch up the damage with watercolor.[20]

The identity of the model

Lisa Gherardini

Giorgio Vasari identified the subject to be the wife of socially prominent Francesco del Giocondo, who was a silk merchant of Florence. Until recently, little was known about his third wife, Lisa Gherardini, except that she was born in 1479, raised at her family's Villa Vignamaggio in Tuscany and that she married del Giocondo in 1495.

In 2004, the Italian scholar Giuseppe Pallanti published Monna Lisa, Mulier Ingenua (literally '"Mona Lisa: Real Woman", published in English under the title Mona Lisa Revealed: The True Identity of Leonardo's Model[21]). The book gathered archival evidence in support of the traditional identification of the model as Lisa Gherardini. According to Pallanti, the evidence suggests that Leonardo's father was a friend of del Giocondo. "The portrait of Mona Lisa, done when Lisa Gherardini was aged about 24, was probably commissioned by Leonardo's father himself for his friends as he is known to have done on at least one other occasion."[22] Pallanti discovered that Lisa and Francesco had five children and that she outlived her husband. In early 2007, Pallanti found a death notice in the archives of a Florence church that referred to "the wife of Francesco del Giocondo, deceased July 15, 1542, and buried at Sant'Orsola." Sant'Orsola is a convent in Florence. Pallanti ascertains with certainty that this refers to Gherardini. This would make her age at her death to be 63 years.[23] Also in January 2007, Italian genealogist Domenico Savini identified the princesses Natalia and Irina Strozzi as living descendants of Lisa Gherardini.[24]

In September 2006, Bruno Mottin argued that the guarnelo he studied using the 2004 scan data suggested that the painting dated from around 1503 and commemorated the birth of Lisa Gherardini's second son Prince Abolo.[25][26]

Other suggestions

Vasari, however, wrote about the portrait, and described it, without ever having seen it; the painting was already in France in Vasari's era. So various alternatives to the traditional sitter have been proposed. During the last years of his life, Leonardo spoke of a portrait "of a certain Florentine lady done from life at the request of the magnificent Giuliano de' Medici." No evidence has been found that indicates a link between Lisa Gherardini and Giuliano de' Medici, but then the comment could instead refer to one of the two other portraits of women executed by Leonardo. A later anonymous statement created confusion when it linked the Mona Lisa to a portrait of Francesco del Giocondo himself — perhaps the origin of the controversial idea that it is the portrait of a man.

Dr. Lillian Schwartz of Bell Labs suggests that the Mona Lisa is actually a self-portrait. She supports this theory with the results of a digital analysis of the facial features of Leonardo's face and that of the famous painting. When flipping a self-portrait drawing by Leonardo and then merging that with an image of the Mona Lisa using a computer, the features of the faces align perfectly.[27] Critics of this theory suggest that the similarities are due to both portraits being painted by the same person using the same style. Additionally, the drawing on which she based the comparison may not be a self-portrait. Serge Bramly, in his biography of Leonardo, discusses the possibility that the portrait depicts the artist's mother Caterina. This would account for the resemblance between artist and subject observed by Dr. Schwartz, and would explain why Leonardo kept the portrait with him wherever he traveled, until his death.

Art historians have also suggested the possibility that the Mona Lisa may only resemble Leonardo by accident: as an artist with a great interest in the human form, Leonardo would have spent a great deal of time studying and drawing the human face, and the face most often accessible to him was his own, making it likely that he would have the most experience with drawing his own features. The similarity in the features of the people depicted in paintings such as the Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist may thus result from Leonardo's familiarity with his own facial features, causing him to draw other, less familiar faces in a similar light.

The art expert Dr. Henry Pulitzer suggested that the portrait was possibly that of Constanza d'Avalos, duchess of Francavilla, a patroness of Leonardo, and mistress of Giuliano de Medici. D'Avalos, coincidentally, was also nicknamed 'La Gioconda'.[28]

Maike Vogt-Lüerssen argues that the woman behind the famous smile is Isabella of Aragon, the Duchess of Milan. Leonardo was the court painter for the Duke of Milan for 11 years. The pattern on Mona Lisa's dark green dress, Vogt-Lüerssen believes, indicates that she was a member of the house of Sforza. Her theory is that the Mona Lisa was the first official portrait of the new Duchess of Milan, which requires that it was painted in spring or summer 1489 (and not 1503). This theory is allegedly supported by another portrait of Isabella of Aragon, painted by Raphael, (Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome).

Aesthetics

Leonardo used a pyramid design to place the woman simply and calmly in the space of the painting. Her folded hands form the front corner of the pyramid. Her breast, neck and face glow in the same light that softly models her hands. The light gives the variety of living surfaces an underlying geometry of spheres and circles. Leonardo referred to a seemingly simple formula for seated female figure: the images of seated Madonna, which were widely spread at the time. He effectively modified this formula in order to create the visual impression of distance between the sitter and the observer. The armrest of the chair functions as a dividing element between Mona Lisa and us. The woman sits markedly upright with her arms folded, which is also a sign of her reserved posture. Only her gaze is fixed on the observer and seems to welcome him to this silent communication. Since the brightly lit face is practically framed with various much darker elements (hair, veil, shadows), the observer's attraction to Mona Lisa's face is brought to even greater extent. Thus, the composition of the figure evokes an ambiguous effect: we are attracted to this mysterious woman but have to stay at a distance as if she were a divine creature. There is no indication of an intimate dialogue between the woman and the observer as is the case in the Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (Louvre) painted by Raphael about ten years after Mona Lisa and undoubtedly influenced by Leonardo's portrait.

The painting was one of the first portraits to depict the sitter before an imaginary landscape. The enigmatic woman is portrayed seated in what appears to be an open loggia with dark pillar bases on either side. Behind her a vast landscape recedes to icy mountains. Winding paths and a distant bridge give only the slightest indications of human presence. The sensuous curves of the woman's hair and clothing, created through sfumato, are echoed in the undulating imaginary valleys and rivers behind her. The blurred outlines, graceful figure, dramatic contrasts of light and dark, and overall feeling of calm are characteristic of Leonardo's style. Due to the expressive synthesis that Leonardo achieved between sitter and the landscape it is arguable whether Mona Lisa should be considered as a portrait, for it represents rather an ideal than a real woman. The sense of overall harmony achieved in the painting — especially apparent in the sitter's faint smile — reflects Leonardo's idea of the cosmic link connecting humanity and nature, making this painting an enduring record of Leonardo's vision and genius.

Mona Lisa's smile has repeatedly been a subject of many - greatly varying - interpretations. Sigmund Freud interpreted the 'smile' as signifying Leonardo's erotic attraction to his dear mother;[29] others have described it as both innocent and inviting. Many researchers have tried to explain why the smile is seen so differently by people. The explanations range from scientific theories about human vision to curious supposition about Mona Lisa's identity and feelings. Professor Margaret Livingstone of Harvard University has argued that the smile is mostly drawn in low spatial frequencies, and so can best be seen from a distance or with one's peripheral vision.[30] Thus, for example, the smile appears more striking when looking at the portrait's eyes than when looking at the mouth itself. Christopher Tyler and Leonid Kontsevich of the Smith-Kettlewell Institute in San Francisco believe that the changing nature of the smile is caused by variable levels of random noise in human visual system.[31] Dina Goldin, Adjunct Professor at Brown University, has argued that the secret is in the dynamic position of Mona Lisa's facial muscles, where our mind's eye unconsciously extends her smile; the result is an unusual dynamicity to the face that invokes subtle yet strong emotions in the viewer of the painting.[32]

In late 2005, Dutch researchers from the University of Amsterdam ran the painting's image through an "emotion recognition" computer software developed in collaboration with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The software found the smile to be 83% happy, 9% disgusted, 6% fearful, 2% angry, less than 1% neutral, and 0% surprised.[33][34] Rather than being a thorough analysis, the experiment was more of a demonstration of the new technology. The faces of ten women of Mediterranean ancestry were used to create a composite image of a neutral expression. Researchers then compared the composite image to the face in the painting. They used a grid to break the smile into small divisions, then checked it for each of six emotions: happiness, surprise, anger, disgust, fear, and sadness.[34]

It is also notable that Mona Lisa has no visible facial hair at all - including eyebrows and eyelashes. Some researchers claim that it was common at this time for genteel women to pluck them off, since they were considered to be unsightly.[35][36] Yet it is more reasonable to assume that Leonardo did not finish the painting, for almost all of his paintings are unfinished. Being a perfectionist he always tried to go one step further in improving his technique. Furthermore, other women of the time were predominantly portrayed with eyebrows. For modern viewers the missing eyebrows add to the slightly semi-abstract quality of the face though it was not Leonardo's aim.

The painting has been restored numerous times; X-ray examinations have shown that there are three versions of the Mona Lisa hidden under the present one. The thin poplar backing is beginning to show signs of deterioration at a higher rate than previously thought, causing concern from museum curators about the future of the painting.

References in art

The avant-garde art world has also taken note of the undeniable fact of the Mona Lisa's popularity. Because of the painting's overwhelming stature, Dadaists and Surrealists often produce modifications and caricatures. In 1919, Marcel Duchamp, one of the most influential Dadaists, made a Mona Lisa parody by adorning a cheap reproduction with a moustache and a goatee, as well as adding the rude inscription L.H.O.O.Q., when read out loud in French sounds like "Elle a chaud au cul" (translating to "she has a hot arse" as a manner of implying the woman in the painting is in a state of sexual excitement and availability). This was intended as a Freudian joke, referring to Leonardo's alleged homosexuality. According to Rhonda R. Shearer, the apparent reproduction is in fact a copy partly modelled on Duchamp's own face.[37] Salvador Dalí, famous for his pioneering surrealist work, painted Self portrait as Mona Lisa in 1954.

In 1963, pop artist Andy Warhol started making colorful serigraph prints of the Mona Lisa. Warhol thus consecrated her as a modern icon, similar to Marilyn Monroe or Elvis Presley. At the same time, his use of a stencil process and crude colors implies a criticism of the debasement of aesthetic values in a society of mass production and mass consumption.

A reproduction of the Mona Lisa was discovered painted onto a hillside near Newport, Oregon on August 15th, 2006. It was created by artist Samuel Clemens using a tarp stencil and water-based paint. Seattle Post-Intelligencer News Article

References in popular culture

The Mona Lisa has acquired an iconic status in popular culture. In "The Mountain Eaters", an episode of the British radio show The Goon Show broadcast on 1 December 1958, the character Neddy Seagoon signed an IOU on the Mona Lisa. Today the Mona Lisa is frequently reproduced, finding its way on to everything from carpets to mouse pads.

It has been a subject of many songs, including:

- Mona Lisa, a song from 1950 by Nat King Cole.

- "Mona Lisa", the first track on country singer Willie Nelson's 1981 album, Somewhere over the Rainbow. The album rose to #1 on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart.[38]

- "Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters" was recorded by Elton John for his album Honky Chateau.

- "A Mona Lisa", an unreleased song by the rock band Counting Crows. It was written by lead singer Adam Duritz and recorded in 1992.[39]

- "Mona Lisa" is also a rare song by Britney Spears.

- Mona Lisa Smile, directed by Mike Newell and featuring Julia Roberts, Kirsten Dunst, and Maggie Gyllenhaal, was released in 2003.

- "Mona Lisa", a song by the German goth band Unheilig suggests her smile is the result of the singer's hand underneath her skirt.[40][41]

In 1979 BBC tv series Doctor Who spoofed the painting's 1911 robbery in City of Death, a storyline involving an alien forcing Leonardo to paint 6 extra copies of the Mona Lisa back in 1505. He then steals the original from the Louvre to sell to 7 different contemporary black market art collectors.

The February 8, 1999 edition of The New Yorker ran for its cover Dean Rohrer's Mona Monica,[42] an amalgamation of the Mona Lisa and Monica Lewinsky.

The painting plays a role in both the book and the movie versions of the fictional The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown.

Parody and imitative versions of the Mona Lisa include a cow, gorilla, mouse, rabbit, and Miss Piggy as Mona Lisa [4].

Notes

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/vinci/joconde/

- ↑ http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn6056

- ↑ Vernon collection copy; Walters Gallery version

- ↑ http://www.lairweb.org.nz/leonardo/mona.html Leonardo da Vinci

- ↑ Charlotte Higgins, "Unveiled: early copy that reveals Mona Lisa as her creator intended", The Guardian, 23 September 2006 (accessed on 23rd September 2006)

- ↑ http://www.nigel-cawthorne.com/projects.htm

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Stealing The Mona Lisa", Time (magazine). Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- ↑ E.H. Net. What is its Relative Value in US Dollars. Accessed on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ CBC. (2006, September 26) [1] Retrieved on September 27, 2006.

- ↑ CNN. (2006, September 26). The Mona Lisa studied in 3D Retrieved on September 25, 2006.

- ↑ Edmonton Journal (September 23) [2] Retrieved on September 27, 2006

- ↑ BBC News. (2005, April 6). Mona Lisa gains new Louvre home. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ Austen, Ian, "New Look at ‘Mona Lisa’ Yields Some New Secrets", The New York Times Online, The New York Times Company, 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre et al. Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting. Abrams, NY

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre et al. Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting. Abrams, NY

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre et al. Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting. Abrams, NY

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre et al. Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting. Abrams, NY

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre et al. Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting. Abrams, NY

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre et al. Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting. Abrams, NY

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre et al. Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting. Abrams, NY

- ↑ Pallanti, G. (2006). Mona Lisa revealed: The true identity of Leonardo's model. Milan: Skira. ISBN 88-7624-659-2

- ↑ Johnston, B. (2004, August 1). Riddle of Mona Lisa is finally solved. Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ Associated Press, 19 January 2007.'Mona Lisa' died in 1542, was buried in convent, Yahoo! News. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

- ↑ The Independent, 28 January 2007. 'The prince, the PM, and the Mona Lisa'. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ↑ CNN. (2006, September 26). The Mona Lisa studied in 3D Retrieved on September 25, 2006.

- ↑ Edmonton Journal (September 23) [3] Retrieved on September 27, 2006

- ↑ Lillian Schwarz's webpage

- ↑ http://www.politicaonline.net/forum/showthread.php?t=45653

- ↑ Freud, S. Leonardo da Vinci and a memory of his childhood. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ BBC News. (2003, February 18). Mona Lisa smile secrets revealed. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ Cohen, P. (2004, June 23). Noisy secret of Mona Lisa's smile. New Scientist. Journal reference: Vision Research (vol 44, p 1493). Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ Goldin, D. (2002, December). Mona Lisa's Secret Revealed. November 1, 2002 draft. Brown University Faculty Bulletin. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ "Mona Lisa 'happy', computer finds". BBC. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Sterling, Toby (2007-12-27). "Mona LIsa Was 83 Percent Happy". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ↑ Turudich, D. & Welch, L. (2003). Plucked, shaved and braided: Medieval and renaissance beauty and grooming practices 1000–1600. Leicester, England: Streamline Press. ISBN 1-930064-08-X

- ↑ McMullen, R. (1975). Mona Lisa: The picture and the myth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-333-19169-2

- ↑ de Martino, M. (2003). Mona Lisa - Who is hidden behind the woman with the moustache? Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ Vitous, P., Pikora, V., Frantik, F., & Gololobov, M. (completion). (1999–2006). LP discography - covers & lyrics: Willie Nelson. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ Fuss, R. (compiler). (2002, June 16). Counting Crows bootleg guide (version 2.59.). Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

- ↑ Unheilig. (2003). Mona Lisa" (song lyrics). Official website. Retrieved on June 21, 2006. (Choose "Das 2. Gebot" under "LYRICS"). An audio sample can be heard at amazon.de ASIN B00008K4EL

- ↑ Unheilig. (2003). "Mona Lisa" (song lyrics). Retrieved on June 21, 2006.

- ↑ Baron, R. (n.d.). Mona Monica. Mona Lisa images for a modern world. Retrieved on June 20, 2006.

See also

- Aerial perspective

- Leonardo da Vinci

External links

- "Why is Mona Lisa so famous?", a video commentary

- Mega Mona Lisa, a large Mona Lisa fan site

- Theft of the Mona Lisa, from the PBS website for Treasures Of The World

- Aging Mona Lisa worries Louvre, an April 2004 BBC article

- The Mona Lisa, another BBC article

- The Mona Lisa photos & photos from Louvre

- Mona Lisa (zoomable version)

- Leonardo da Vinci, Gallery of Paintings and Drawings

- Unmasking the Mona Lisa: Expert claims to have discovered da Vinci's technique

- Who is Mona Lisa? Historical Facts versus Conjectures

- Mona Lisa's voice simulated

- "Mona Lisa had a makeover, 3D images reveal", Cosmos magazine, September 2006

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.