Difference between revisions of "Maurya Empire" - New World Encyclopedia

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) |

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{help|Extraneous br:Patrom:Rouantelezhioù marevezh kreiz India at the bottom of article.}} | {{help|Extraneous br:Patrom:Rouantelezhioù marevezh kreiz India at the bottom of article.}} | ||

{{Maurya Empire infobox}} | {{Maurya Empire infobox}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Emblem of India.svg|thumb|200px| A representation of the [[Lion Capital of Ashoka]], erected around 250 B.C.E., the [[emblem of India]].]] | ||

| + | [[Image:MauryaStatuettes.jpg|thumb|400px|Statuettes of the Maurya period, fourth-third century B.C.E. [[Musée Guimet]].]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | The '''Maurya Empire''' ([[322 B.C.E..|322]]–[[185 B.C.E.|185]] B.C.E.), ruled by the Mauryan dynasty, was a geographically extensive and [[great power|powerful]] political and military [[empire]] in [[history of India|ancient India]]. Originating from the kingdom of [[Magadha]] in the [[Indo-Gangetic plains]] (modern [[Bihar]], Eastern [[Uttar Pradesh]] and [[Bengal]]) in the eastern side of the sub-continent, the empire had its capital city at [[Pataliputra]] (near modern [[Patna]]). [[Chandragupta Maurya]] founded the Empire in 322 B.C.E. He had overthrown the [[Nanda Dynasty]] and began rapidly expanding his power westwards across central and western [[India]] taking advantage of the disruptions of local [[power (international)|powers]] in the wake of the withdrawal westward by [[Alexander the Great]]'s Macedonian and Persian armies. By 316 B.C.E. the empire had fully occupied Northwestern India, defeating and conquering the satraps left by Alexander. |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | At its greatest extent, the Empire stretched to the north along the natural boundaries of the [[Himalayas]], and to the east stretching into [[Assam]]. To the west, it reached beyond modern [[Pakistan]] and significant portions of [[Afghanistan]], including the modern [[Herat Province|Herat]] and [[Kandahar Province|Kandahar]] provinces and [[Balochistan (Pakistan)|Balochistan]]. Emperor [[Bindusara]] expanded the Empire into India's central and southern regions, but it excluded a small portion of unexplored tribal and forested regions near [[Kalinga (India)|Kalinga]]. | |

| − | + | The Mauryan Empire was perhaps the largest empire to rule the Indian subcontinent. Its decline began fifty years after Ashoka's rule ended, and it dissolved in 185 B.C.E. with the foundation of the [[Sunga Dynasty]] in Magadha. Under [[Chandragupta]], the Mauryan Empire conquered the trans-Indus region, which was under Macedonian rule. Chandragupta then defeated the invasion led by [[Seleucus I Nicator|Seleucus I]], a Greek general from Alexander's army. Under Chandragupta and his successors, both internal and external trade, and agriculture and economic activities, all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration and security. | |

| − | + | After the [[Kalinga War]], the Empire experienced half a century of peace and security under Ashoka: India was a prosperous and stable empire of great economic and military power whose political influence and trade extended across Western and Central Asia and Europe. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of [[Jainism]] increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of [[Buddhism]] was the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across all of India. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist ideals into [[Sri Lanka]], Southeast Asia, West Asia and Mediterranean Europe. | |

| − | + | Chandragupta's minister [[Kautilya Chanakya]] wrote the ''[[Arthashastra]]'', one of the greatest treatises on [[economics]], politics, foreign affairs, administration, military arts, war, and religion ever produced in the East. Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of [[Northern Black Polished Ware]] (NBPW). The ''Arthashastra'' and the [[Edicts of Ashoka]] serve as primary sources of written records of the Mauryan times. The Mauryan empire stands as one of the most significant periods in Indian history. The ''[[Lion Capital of Asoka]]'' at [[Sarnath]], is the [[emblem of India]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Chandragupta's minister [[Kautilya Chanakya]] wrote the ''[[Arthashastra]]'', one of the greatest treatises on [[economics]], politics, foreign affairs, administration, military arts, war, and religion ever produced in the East. Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of [[Northern Black Polished Ware]] (NBPW). The ''Arthashastra'' and the [[Edicts of Ashoka]] | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

Revision as of 23:27, 7 September 2008

The Maurya Empire at its largest extent under Ashoka the Great. | |

| Imperial Symbol: The Lion Capital of Ashoka | |

| Founder | Chandragupta Maurya |

|---|---|

| Preceding State(s) | Nanda Dynasty of Magadha Mahajanapadas |

| Languages | Pali Prakrit Sanskrit |

| Religions | Buddhism Hinduism Jainism |

| Capital | Pataliputra |

| Head of State | Samraat (Emperor) |

| First Emperor | Chandragupta Maurya |

| Last Emperor | Brhadrata |

| Government | Centralized Absolute Monarchy with Divine Right of Kings as described in the Arthashastra |

| Divisions | 4 provinces: Tosali Ujjain Suvarnagiri Taxila Semi-independent tribes |

| Administration | Inner Council of Ministers (Mantriparishad) under a Mahamantri with a larger assembly of ministers (Mantrinomantriparisadamca). Extensive network of officials from treasurers (Sannidhatas) to collectors (Samahartas) and clerks (Karmikas). Provincial administration under regional viceroys (Kumara or Aryaputra) with their own Mantriparishads and supervisory officials (Mahamattas). Provinces divided into districts run by lower officials and similar stratification down to individual villages run by headmen and supervised by Imperial officials (Gopas). |

| Area | 5 million km² (Southern Asia and parts of Central Asia) |

| Population | 50 million [1] (one third of the world population [2]) |

| Currency | Silver Ingots (Panas) |

| Existed | 322–185 B.C.E. |

| Dissolution | Military coup by Pusyamitra Sunga |

| Succeeding state | Sunga Empire |

The Maurya Empire (322–185 B.C.E.), ruled by the Mauryan dynasty, was a geographically extensive and powerful political and military empire in ancient India. Originating from the kingdom of Magadha in the Indo-Gangetic plains (modern Bihar, Eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bengal) in the eastern side of the sub-continent, the empire had its capital city at Pataliputra (near modern Patna). Chandragupta Maurya founded the Empire in 322 B.C.E. He had overthrown the Nanda Dynasty and began rapidly expanding his power westwards across central and western India taking advantage of the disruptions of local powers in the wake of the withdrawal westward by Alexander the Great's Macedonian and Persian armies. By 316 B.C.E. the empire had fully occupied Northwestern India, defeating and conquering the satraps left by Alexander.

At its greatest extent, the Empire stretched to the north along the natural boundaries of the Himalayas, and to the east stretching into Assam. To the west, it reached beyond modern Pakistan and significant portions of Afghanistan, including the modern Herat and Kandahar provinces and Balochistan. Emperor Bindusara expanded the Empire into India's central and southern regions, but it excluded a small portion of unexplored tribal and forested regions near Kalinga.

The Mauryan Empire was perhaps the largest empire to rule the Indian subcontinent. Its decline began fifty years after Ashoka's rule ended, and it dissolved in 185 B.C.E. with the foundation of the Sunga Dynasty in Magadha. Under Chandragupta, the Mauryan Empire conquered the trans-Indus region, which was under Macedonian rule. Chandragupta then defeated the invasion led by Seleucus I, a Greek general from Alexander's army. Under Chandragupta and his successors, both internal and external trade, and agriculture and economic activities, all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration and security.

After the Kalinga War, the Empire experienced half a century of peace and security under Ashoka: India was a prosperous and stable empire of great economic and military power whose political influence and trade extended across Western and Central Asia and Europe. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of Jainism increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism was the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across all of India. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist ideals into Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West Asia and Mediterranean Europe.

Chandragupta's minister Kautilya Chanakya wrote the Arthashastra, one of the greatest treatises on economics, politics, foreign affairs, administration, military arts, war, and religion ever produced in the East. Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). The Arthashastra and the Edicts of Ashoka serve as primary sources of written records of the Mauryan times. The Mauryan empire stands as one of the most significant periods in Indian history. The Lion Capital of Asoka at Sarnath, is the emblem of India.

Background

Alexander set up a Macedonian garrison and satrapies (vassal states) in the trans-Indus region of modern day Pakistan, ruled previously by kings Ambhi of Taxila and Porus of Pauravas (modern day Jhelum).

Chanakya and Chandragupta Maurya

Following Alexander's advance into the Punjab, a brahmin named Chanakya (real name Vishnugupt, also known as Kautilya) traveled to Magadha, a kingdom that was large and militarily-powerful and feared by its neighbors, but was dismissed by its king Dhana, of the Nanda Dynasty. However, the prospect of battling Magadha deterred Alexander's troops from going further east: he returned to Babylon, and re-deployed most of his troops west of the Indus river. When Alexander died in Babylon, soon after in 323 B.C.E., his empire fragmented, and local kings declared their independence, leaving several smaller satraps in a disunited state. Chandragupta Maurya deposed Dhana. The Greek generals Eudemus, and Peithon, ruled until around 316 B.C.E., when Chandragupta Maurya (with the help of Chanakya, who was now his advisor) surprised and defeated the Macedonians and consolidated the region under the control of his new seat of power in Magadha.

Chandragupta Maurya's rise to power is shrouded in mystery and controversy. On the one hand, a number of ancient Indian accounts, such as the drama Mudrarakshasa (Poem of Rakshasa - Rakshasa was the prime minister of Magadha) by Visakhadatta, describe his royal ancestry and even link him with the Nanda family. A kshatriya tribe known as the Maurya's are referred to in the earliest Buddhist texts, Mahaparinibbana Sutta. However, any conclusions are hard to make without further historical evidence. Chandragupta first emerges in Greek accounts as "Sandrokottos." As a young man he is said to have met Alexander.[3] He is also said to have met the Nanda king, angered him, and made a narrow escape.[4] Chanakya's original intentions were to train a guerilla army under Chandragupta's command. The Mudrarakshasa of Visakhadutta as well as the Jaina work Parisishtaparvan talk of Chandragupta's alliance with the Himalayan king Parvatka, sometimes identified with Porus (John Marshall "Taxila," p18, and al.) This Himalayan alliance gave Chandragupta a composite and powerful army made up of Yavanas (Greeks), Kambojas, Shakas (Scythians), Kiratas (Nepalese), Parasikas (Persians) and Bahlikas (Bactrians)[5] [6].

With the help of these frontier martial tribes from Central Asia, Chandragupta was able to defeat the Nanda/Nandin rulers of Magadha and found the powerful Maurya empire in northern India.

Conquest of Magadha

Chanakya encouraged Chandragupta and his army to take over the throne of Magadha. Using his intelligence network, Chandragupta gathered many young men from across Magadha and other provinces, men upset over the corrupt and oppressive rule of king Dhana, plus resources necessary for his army to fight a long series of battles. These men included the former general of Taxila, other accomplished students of Chanakya, the representative of King Porus of Kakayee, his son Malayketu, and the rulers of small states.

Preparing to invade Pataliputra, Maurya hatched a plan. A battle was announced and the Magadhan army was drawn from the city to a distant battlefield to engage Maurya's forces. Maurya's general and spies meanwhile bribed the corrupt general of Nanda. He also managed to create an atmosphere of civil war in the kingdom, which culminated in the death of the heir to the throne. Chanakya managed to win over popular sentiment. Ultimately Nanda resigned, handing power to Chandragupta, and went into exile and was never heard of again. Chanakya contacted the prime minister, Rakshasas, and made him understand that his loyalty was to Magadha, not to the Magadha dynasty, insisting that he continue in office. Chanakya also reiterated that choosing to resist would start a war that would severely affect Magadha and destroy the city. Rakshasa accepted Chanakya's reasoning, and Chandragupta Maurya was legitimately installed as the new King of Magadha. Rakshasa became Chandragupta's chief advisor, and Chanakya assumed the position of an elder statesman.

The approximate extent of the Magadha state in the 5th century B.C.E.

The Maurya Empire when it was first founded by Chandragupta Maurya circa 320 B.C.E., after conquering the Nanda Empire when he was only about 20 years old.

Chandragupta extended the borders of the Maurya Empire towards Seleucid Persia after defeating Seleucus circa 305 B.C.E.[citation needed]

Chandragupta extended the borders of the empire southward into the Deccan Plateau circa 300 B.C.E.[7]

Ashoka the Great extended into Kalinga during the Kalinga War circa 265 B.C.E., and established superiority over the southern kingdoms.

Building India's First Empire

Having become the king of one of India's most powerful states, Chandragupta invaded the Punjab. One of Alexander's richest satraps, Peithon, satrap of Media, had tried to raise a coalition against him. Chandragupta managed to conquer the Punjab capital of Taxila, an important centre of trade and Hellenistic culture, increasing his power and consolidating his control.

Chandragupta Maurya

| Approximate Dates of Mauryan Dynasty | ||||||||||||

| Emperor | Reign start | Reign end | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chandragupta Maurya | 322 B.C.E. | 298 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Bindusara | 297 B.C.E. | 272 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Asoka The Great | 273 B.C.E. | 232 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Dasaratha | 232 B.C.E. | 224 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Samprati | 224 B.C.E. | 215 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Salisuka | 215 B.C.E. | 202 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Devavarman | 202 B.C.E. | 195 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Satadhanvan | 195 B.C.E. | 187 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

| Brihadratha | 187 B.C.E. | 185 B.C.E. | ||||||||||

Chandragupta was again in conflict with the Greeks when Seleucus I, ruler of the Seleucid Empire, tried to reconquer the northwestern parts of India, during a campaign in 305 B.C.E., but failed. The two rulers finally concluded a peace treaty: a marital treaty (Epigamia) was concluded, implying either a marital alliance between the two dynastic lines or a recognition of marriage between Greeks and Indians, Chandragupta received the satrapies of Paropamisadae (Kamboja and Gandhara), Arachosia (Kandhahar) and Gedrosia (Balochistan), and Seleucus I received 500 war elephants that were to have a decisive role in his victory against western Hellenistic kings at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 B.C.E. Diplomatic relations were established and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, Deimakos and Dionysius resided at the Mauryan court.

Chandragupta established a strong centralized state with a complex administration at Pataliputra, which, according to Megasthenes, was "surrounded by a wooden wall pierced by 64 gates and 570 towers—(and) rivaled the splendors of contemporaneous Persian sites such as Susa and Ecbatana." Chandragupta's son Bindusara extended the rule of the Mauryan empire towards southern India. He also had a Greek ambassador at his court, named Deimachus (Strabo 1–70). Megasthenes describes a disciplined multitude under Chandragupta, who live simply, honestly, and do not know writing.[8]

Bindusara

Chandragupta died after a reign for 24 years and was succeeded by his son, Bindusara, also known as Amitrochates (destroyer of foes) in Greek accounts, around 298 B.C.E.[9] Details are scarce regarding Bindusara; however, the incorporation of southern peninsular India is sometimes credited to him. According to Jain tradition, his mother was a woman by the name of Durdhara. The Puranas assign him a reign of 25 years. He has been identified with the Indian title Amitraghata (slayer of Enemies), found in Greek texts as Amitrochates.

Ashoka the Great

Chandragupta's grandson Ashokavardhan Maurya, better known as Ashoka the Great (ruled 273- 232 B.C.E.), is considered by contemporary historians to be perhaps the greatest of Indian monarchs, and perhaps the world. H.G. Wells calls him the "greatest of kings."

As a young prince, Ashoka was a brilliant commander who crushed revolts in Ujjain and Taxila. As monarch he was ambitious and aggressive, re-asserting the Empire's superiority in southern and western India. But it was his conquest of Kalinga which proved to be the pivotal event of his life. Although Ashoka's army succeeded in overwhelming Kalinga forces of royal soldiers and civilian units, an estimated 100,000 soldiers and civilians were killed in the furious warfare, including over 10,000 of Ashoka's own men. Hundreds of thousands of people were adversely affected by the destruction and fallout of war. When he personally witnessed the devastation, Ashoka began feeling remorse, and he cried 'what have I done?'. Although the annexation of Kalinga was completed, Ashoka embraced the teachings of Gautama Buddha, and renounced war and violence. For a monarch in ancient times, this was an historic feat.

Ashoka implemented principles of ahimsa by banning hunting and violent sports activity and ending indentured and forced labor (many thousands of people in war-ravaged Kalinga had been forced into hard labor and servitude). While he maintained a large and powerful army, to keep the peace and maintain authority, Ashoka expanded friendly relations with states across Asia and Europe, and he sponsored Buddhist missions. He undertook a massive public works building campaign across the country. Over 40 years of peace, harmony and prosperity made Ashoka one of the most successful and famous monarchs in Indian history. He remains an idealized figure of inspiration in modern India.

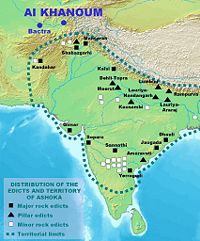

The Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, are found throughout the Subcontinent. Ranging from as far west as Afghanistan and as far south as Andhra (Nellore District), Ashoka's edicts state his policies and accomplishments. Although predominantly written in Prakrit, two of them were written in Greek, and one in both Greek and Aramaic. Ashoka's edicts refer to the Greeks, Kambojas, and Gandharas as peoples forming a frontier region of his empire. They also attest to Ashoka's having sent envoys to the Greek rulers in the West as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts precisely name each of the rulers of the Hellenic world at the time such as Amtiyoko (Antiochus), Tulamaya (Ptolemy), Amtikini (Antigonos), Maka (Magas) and Alikasudaro (Alexander) as recipients of Ashoka's proselytism. The Edicts also accurately locate their territory "600 yojanas away" (a yojanas being about 7 miles), corresponding to the distance between the center of India and Greece (roughly 4,000 miles).[11]

Administration

The Empire was divided into four provinces, with the imperial capital at Pataliputra. From Ashokan edicts, the names of the four provincial capitals are Tosali (in the east), Ujjain in the west, Suvarnagiri (in the south), and Taxila (in the north). The head of the provincial administration was the Kumara (royal prince), who governed the provinces as king's representative. The kumara was assisted by Mahamatyas and council of ministers. This organizational structure was reflected at the imperial level with the Emperor and his Mantriparishad (Council of Ministers).

Historians theorize that the organization of the Empire was in line with the extensive bureaucracy described by Kautilya in the Arthashastra: a sophisticated civil service governed everything from municipal hygiene to international trade. The expansion and defense of the empire was made possible by what appears to have been the largest standing army of its time.[12] According to Megasthenes, the empire wielded a military of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants. A vast espionage system collected intelligence for both internal and external security purposes. Having renounced offensive warfare and expansionism, Ashoka nevertheless continued to maintain this large army, to protect the Empire and instill stability and peace across West and South Asia.[13]

Economy

For the first time in South Asia, political unity and military security allowed for a common economic system and enhanced trade and commerce, with increased agricultural productivity. The previous situation involving hundreds of kingdoms, many small armies, powerful regional chieftains, and internecine warfare, gave way to a disciplined central authority. Farmers were freed of tax and crop collection burdens from regional kings, paying instead to a nationally-administered and strict-but-fair system of taxation as advised by the principles in the Arthashastra. Chandragupta Maurya established a single currency across India, and a network of regional governors and administrators and a civil service provided justice and security for merchants, farmers and traders. The Mauryan army wiped out many gangs of bandits, regional private armies, and powerful chieftains who sought to impose their own supremacy in small areas. Although regimental in revenue collection, Maurya also sponsored many public works and waterways to enhance productivity, while internal trade in India expanded greatly due to newfound political unity and internal peace.

Under the Indo-Greek friendship treaty, and during Ashoka's reign, an international network of trade expanded. The Khyber Pass, on the modern boundary of Pakistan and Afghanistan, became a strategically-important port of trade and intercourse with the outside world. Greek states and Hellenic kingdoms in West Asia became important trade partners of India. Trade also extended through the Malay peninsula into Southeast Asia. India's exports included silk goods and textiles, spices and exotic foods. The Empire was enriched further with an exchange of scientific knowledge and technology with Europe and West Asia. Ashoka also sponsored the construction of thousands of roads, waterways, canals, hospitals, rest-houses and other public works. The easing of many overly-rigorous administrative practices, including those regarding taxation and crop collection, helped increase productivity and economic activity across the Empire.

In many ways, the economic situation in the Maurya Empire is comparable to the Roman Empire several centuries later, which both had extensive trade connections and both had organizations similar to corporations. While Rome had organizational entities which were largely used for public state-driven projects, Mauryan India had numerous private commercial entities which existed purely for private commerce. This was due to the Mauryas having to contend with pre-existing private commercial entities hence they were more concerned about keeping the support of these pre-existing organizations, while the Romans did not have such pre-existing entities to contend with hence they were able to prevent such entities from developing.[14] (See also Economic history of India.)

Religion

Jainism

Emperor Chandragupta Maurya became the first major Indian monarch to initiate a religious transformation at the highest level when he embraced Jainism, a religious movement resented by orthodox Hindu priests who usually attended the imperial court. At an older age, Chandragupta renounced his throne and material possessions to join a wandering group of Jain monks. Chandragupta was a disciple of Acharya Bhadrabahu. It is said that in his last days, he observed the rigorous but self purifying Jain ritual of santhara i.e. fast unto death, at Shravan Belagola in Karnatka.However, his successor, Emperor Bindusara, preserved Hindu traditions and distanced himself from Jain and Buddhist movements.Samprati, the grandson of Ashoka also embraced Jainism. Samrat Samprati was influenced by the teachings of Jain monk Arya Suhasti Suri and he is known to have built 1,25,000 Jain Temples across India. Some of them are still found in towns of Ahmedabad, Viramgam, Ujjain & Palitana. It is also said that just like Ashoka, Samprati sent messengers & preachers to Greece, Persia & middle-east for the spread of Jainism. But till date no research has been done in this area. Thus, Jainism became a vital force under the Mauryan Rule. Chandragupta & Samprati, are credited for spread of Jainism in Southern India. Lakhs of Jain Temples & Jain Stupas were erected during their reign. But due to lack of royal patronage & its strict principles, along with rise of Shankaracharya & Ramanujacharya, Jainism,once the major religion of southern India, declined.

Buddhism

But when Ashoka embraced Buddhism, following the Kalinga War, he renounced expansionism and aggression, and the harsher injunctions of the Arthashastra on the use of force, intensive policing, and ruthless measures for tax collection and against rebels. Ashoka sent a mission led by his son and daughter to Sri Lanka, whose king Tissa was so charmed with Buddhist ideals that he adopted them himself and made Buddhism the state religion. Ashoka sent many Buddhist missions to West Asia, Greece and South East Asia, and commissioned the construction of monasteries, schools and publication of Buddhist literature across the empire. He is believed to have built as many as 84,000 stupas across India, and he increased the popularity of Buddhism in Afghanistan. Ashoka helped convene the Third Buddhist Council of India and South Asia's Buddhist orders, near his capital, a council that undertook much work of reform and expansion of the Buddhist religion.

Hinduism

While himself a Buddhist, Ashoka retained the membership of Hindu priests and ministers in his court, and he maintained religious freedom and tolerance although the Buddhist faith grew in popularity with his patronage. Indian society began embracing the philosophy of ahimsa, and given the increased prosperity and improved law enforcement, crime and internal conflicts reduced dramatically. Also greatly discouraged was the caste system and orthodox discrimination, as Hinduism began to absorb the ideals and values of Jain and Buddhist teachings. Social freedom began expanding in an age of peace and prosperity.

Architectural remains

Architectural remains of the Maurya period are rather few. Remains of a hypostyle building with about 80 columns of a height of about 10 meters have been found in Kumhrar, 5 km from Patna Railway station, and is one of the very few site that has been connected to the rule of the Mauryas in that city. The style is rather reminiscent of Persian Achaemenid architecture.[16]

The grottoes of Barabar Caves, are another example of Mauryan architecture, especially the decorated front of the Lomas Rishi grotto. These were offered by the Mauryas to the Buddhist sect of the Ajivikas.[17]

The most widespread example of Maurya architecture are the Pillars of Ashoka, often exquisitely decorated, with more than 40 spread throughout the sub-continent.

Natural history in the times of the Mauryas

The protection of animals in India became serious business by the time of the Maurya dynasty; being the first empire to provide a unified political entity in India, the attitude of the Mauryas towards forests, its denizens and fauna in general is of interest.

The Mauryas firstly looked at forests as a resource. For them, the most important forest product was the elephant. Military might in those times depended not only upon horses and men but also battle-elephants; these played a role in the defeat of Seleucus, Alexander's governor of the Punjab. The Mauryas sought to preserve supplies of elephants since it was cheaper and took less time to catch, tame and train wild elephants than to raise them. Kautilya's Arthashastra contains not only maxims on ancient statecraft, but also unambiguously specifies the responsibilities of officials such as the Protector of the Elephant Forests.[18]

The Mauryas also designated separate forests to protect supplies of timber, as well as lions and tigers, for skins. Elsewhere the Protector of Animals also worked to eliminate thieves, tigers and other predators to render the woods safe for grazing cattle.

The Mauryas valued certain forest tracts in strategic or economic terms and instituted curbs and control measures over them. They regarded all forest tribes with distrust and controlled them with bribery and political subjugation. They employed some of them, the food-gatherers or aranyaca to guard borders and trap animals. The sometimes tense and conflict-ridden relationship nevertheless enabled the Mauryas to guard their vast empire.[19]

When Ashoka embraced Buddhism in the latter part of his reign, he brought about significant changes in his style of governance, which included providing protection to fauna, and even relinquished the royal hunt. He was perhaps the first ruler in history to advocate conservation measures for wildlife and even had rules inscribed in stone edicts. The edicts proclaim that many followed the king's example in giving up the slaughter of animals; one of them proudly states:[19]

Our king killed very few animals.

Edict on Fifth Pillar

However, the edicts of Ashoka reflect more the desire of rulers than actual events; the mention of a 100 'panas' (coins) fine for poaching deer in royal hunting preserves shows that rule-breakers did exist. The legal restrictions conflicted with the practices freely exercised by the common people in hunting, felling, fishing and setting fires in forests.[19]

Contacts with the Hellenistic world

Foundation of the Empire

Relations with the Hellenistic world may have started from the very beginning of the Maurya Empire. Plutarch reports that Chandragupta Maurya met with Alexander the Great, probably around Taxila in the northwest.[20]

Reconquest of the Northwest (c. 310 B.C.E.)

Chandragupta ultimately occupied Northwestern India, in the territories formerly ruled by the Greeks, where he fought the satraps (described as "Prefects" in Western sources) left in place after Alexander (Justin), among whom may have been Eudemus, ruler in the western Punjab until his departure in 317 B.C.E. or Peithon, son of Agenor, ruler of the Greek colonies along the Indus until his departure for Babylon in 316 B.C.E.[21]

Conflict and alliance with Seleucus (305 B.C.E.)

Seleucus I Nicator, the Macedonian satrap of the Asian portion of Alexander's former empire, conquered and put under his own authority eastern territories as far as Bactria and the Indus (Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55), until in 305 B.C.E. he entered in a confrontation with Chandragupta.[22]

Though no accounts of the conflict remain, it is clear that Seleucus fared poorly against the Indian Emperor as he failed in conquering any territory, and in fact, was forced to surrender much that was already his. Regardless, Seleucus and Chandragupta ultimately reached a settlement and through a treaty sealed in 305 B.C.E., Seleucus, according to Strabo, ceded a number of territories to Chandragupta, including southern Afghanistan and parts of Persia.

Accordingly, Seleucus obtained five hundred war elephants, a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 B.C.E.

Marital alliance

A matrimonial alliance was also agreed upon (called Epigamia in ancient sources, meaning either the recognition of marriage between trans-indus inhabitants and Greeks, or a dynastic alliance)[23]

It is generally thought that there was an marital alliance made between a Seleucid princess and Chandragupta, and that the Seleucid princess may have been bethrothed to the Mauryan Dynasty. This practice in itself was quite common in the Hellenistic world to formalize alliances. There is thus a possibility that some of the descendants of Chandragupta were partly of Hellenic descent, whether Chandragupta married the Seleucid princess, or his son Bindusara, and that the Maurya dynasty was considered as closely connected to the Seleucid one.[24] Bindusara himself, born earlier around 320 B.C.E., could not have been the result of such a union, but he may have been the one who married the Seleucid princess, just before his rise as Emperor in 298 B.C.E.[25]

Although Indian sources mention him as the son of brahmin woman, the marriage arrangement has led some to suggest that Ashoka may have been a product of this union with a Seleucid princess[26] although the general view is that Ashoka was born from a Brahmin mother who was a minor queen of Bindusara, based on the account of the 2nd century CE Ashokavadana ("Legend of Ashoka").[27] The practice of Mauryan rulers to have harems is repeatedly mentioned in sources such as the Ashokavadana however, which would suggest a multiplicity of bloodlines and a numerous descent for each king.

At the very least, this treaty on "Epigamia" implies lawful marriage between Greeks and Indians was recognized at the State level, although it is unclear whether it occurred among dynastic rulers or common people, or both.

Exchange of ambassadors

Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (Modern Patna in Bihar state). Later Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[28]

Exchange of presents

Classical sources have also recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus.[29]

His son Bindusara 'Amitraghata' (Slayer of Enemies) also is recorded in Classical sources as having exchanged present with Antiochus I.[30]

Greek populations in India

Greek populations apparently remained in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Ashoka's rule. In his Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, Ashoka describes that Greek populations within his realm converted to Buddhism.

Fragments of Edict 13 have been found in Greek, and a full Edict, written in both Greek and Aramaic has been discovered in Kandahar. It is said to be written in excellent Classical Greek, using sophisticated philosophical terms. In this Edict, Ashoka uses the word Eusebeia ("Piety") as the Greek translation for the ubiquitous "Dharma" of his other Edicts written in Prakrit.[31]

Buddhist missions to the West (c.250 B.C.E.)

Also, in the Edicts of Ashoka, Ashoka mentions the Hellenistic kings of the period as a recipient of his Buddhist proselytism, although no Western historical record of this event remain. Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in their territories. The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek ("Yona") Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism (the Mahavamsa, XII[32]).

Subhagsena and Antiochos III (206 B.C.E.)

Sophagasenus was an Indian Mauryan ruler of the 3rd century B.C.E., described in ancient Greek sources, and named Subhagsena or Subhashsena in Prakrit. His name is mentionned in the list of Mauryan princes[citation needed], and also in the list of the Yadava dynasty, as a descendant of Pradyumana. He may have been a grandson of Ashoka, or Kunala, the son of Ashoka. He ruled an area south of the Hindu Kush, possibly in Gandhara. Antiochos III, the Seleucid king, after having made peace with Euthydemus in Bactria, went to India in 206 B.C.E. and is said to have renewed his friendship with the Indian king there.[33]

Decline

Ashoka was followed for 50 years by a succession of weaker kings. Brhadrata, the last ruler of the Mauryan dynasty, held territories that had shrunk considerably from the time of emperor Ashoka, although he still upheld the Buddhist faith.

Sunga coup (185 B.C.E.)

He was assassinated in 185 B.C.E. during a military parade, by the commander-in-chief of his guard, the Brahmin general Pusyamitra Sunga, who then took over the throne and established the Sunga dynasty. Buddhist records such as the Asokavadana write that the assassination of Brhadrata and the rise of the Sunga empire led to a wave of persecution for Buddhists,[34] and a resurgence of Hinduism. According to John Marshall,[35] Pusyamitra may have been the main author of the persecutions, although later Sunga kings seem to have been more supportive of Buddhism. Other historians, such as Etienne Lamotte[36] andRomila Thapar,[37] among others, have argued that archaeological evidence in favor of the allegations of persecution of Buddhists are lacking, and that the extent and magnitude of the atrocities have been exaggerated.

Establishment of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 B.C.E.)

The fall of the Mauryas left the Khyber Pass unguarded, and a wave of foreign invasion followed. The Greco-Bactrian king, Demetrius, capitalized on the break-up, and he conquered southern Afghanistan and Pakistan around 180 B.C.E., forming the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Greeks would maintain holdings on the trans-Indus region, and make forays into central India, for about a century. Under them, Buddhism flourished, and one of their kings Menander became a famous figure of Buddhism, he was to establish a new capital of Sagala, the modern city of Sialkot. However, the extent of their domains and the lengths of their rule are subject to much debate. Numismatic evidence indicates that they retained holdings in the subcontinent right up to the birth of Christ. Although the extent of their successes against indigenous powers such as the Sungas, Satavahanas, and Kalingas are unclear, what is clear is that Scythian tribes, renamed Indo-Scythians, brought about the demise of the Indo-Greeks from around 70 B.C.E. and retained lands in the trans-Indus, the region of Mathura, and Gujarat.

The Empire To Modern Indians

Having been India's first major empire, the Maurya Empire holds a special place in the minds of Indian people: Indians feel pride to this day in recalling the great political and military power the Empire held in its day, and the spirituality and piety of Ashoka, who kept war and violence away from his people. The media in India also has produced works based upon Mauryan times:

- Chanakya (early 1990s) was a Hindi television series that depicted the life and philosophy of Kautilya Chanakya, from fighting Alexander's invasion to the coronation of Chandragupta Maurya. Directed by Dr. Chandraprakash Dwivedi starring Dr. Chandraprakash Dwivedi himself as Chanakya and Animesh Dwivedi as Chandragupta Maurya.

- Asoka (2001) is a Hindi film by Santosh Sivan starring Shahrukh Khan as the Emperor Ashoka, depicting his aggressive youth, early impetuous rule, and his transformation following the war in Kalinga. The film, however, does not claim that its portrayal of Ashoka's life is historically accurate.

- Chanakya Chandragupta (1977) is Telugu film by N.T. Rama Rao starring legendary actors Akkineni Nageswara Rao as Chanakya and N.T. Rama Rao as Chandragupta Maurya.

Notes

| History of South Asia History of India | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone Age | 70,000–3300 B.C.E. | ||||

| · Mehrgarh Culture | · 7000–3300 B.C.E. | ||||

| Indus Valley Civilization | 3300–1700 B.C.E. | ||||

| Late Harappan Culture | 1700–1300 B.C.E. | ||||

| Vedic Period | 1500–500 B.C.E. | ||||

| · Iron Age Kingdoms | · 1200–700 B.C.E. | ||||

| Maha Janapadas | 700–300 B.C.E. | ||||

| Magadha Kingdom | 1700 B.C.E.–550 C.E. | ||||

| · Maurya Dynasty | · 321–184 B.C.E. | ||||

| Middle Kingdoms | 230 B.C.E.–AD 1279 | ||||

| · Satavahana Empire | · 230 B.C.E.–AD 199 | ||||

| · Kushan Empire | · 60–240 | ||||

| · Gupta Empire | · 240–550 | ||||

| · Pala Empire | · 750–1174 | ||||

| · Chola Empire | · 848–1279 | ||||

| Islamic Sultanates | 1206–1596 | ||||

| · Delhi Sultanate | · 1206–1526 | ||||

| · Deccan Sultanates | · 1490–1596 | ||||

| Hoysala Empire | 1040–1346 | ||||

| Kakatiya Empire | 1083–1323 | ||||

| Vijayanagara Empire | 1336–1565 | ||||

| Mughal Empire | 1526–1707 | ||||

| Maratha Empire | 1674–1818 | ||||

| Colonial Era | 1757–1947 | ||||

| Modern States | 1947 onwards | ||||

| State histories Bangladesh · Bhutan · Republic of India Maldives · Nepal · Pakistan · Sri Lanka | |||||

| Regional histories Assam · Bengal · Pakistani Regions Punjab · Sindh · South India · Tibet | |||||

| Specialised histories Dynasties · Economy · Indology · Language · Literature Maritime · Military · Science and Technology · Timeline | |||||

- ↑ Roger Boesche, "Kautilya’s Arthashastra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India", The Journal of Military History 67 (2003): 12.

- ↑ Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones, "Atlas of World Population History", Facts on File (1978): 342-351.

- ↑ :"Androcottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth." Plutarch 62-3 Plutarch 62-3

- ↑ :"He was of humble origin, but was pushing to acquiring the throne by the superior power of the mind. When after having offensed the king of Nanda by his insolence, he was comdemned to death by the king, he was saved by the speed of his own feet... He gathered bandits and invited Indian to a change of rule." Justin XV.4.15 "Fuit hic humili quidem genere natus, sed ad regni potestatem maiestate numinis inpulsus. Quippe cum procacitate sua Nandrum regem offendisset, interfici a rege iussus salutem pedum ceieritate quaesierat. (Ex qua fatigatione cum somno captus iaceret, leo ingentis formae ad dormientem accessit sudoremque profluentem lingua ei detersit expergefactumque blande reliquit. Hoc prodigio primum ad spem regni inpulsus) contractis latronibus Indos ad nouitatem regni sollicitauit." Justin XV.4.15. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ↑

- "asti tava Shaka-Yavana-Kirata-Kamboja-Parasika-Bahlika parbhutibhih

- Chankyamatipragrahittaishcha Chandergupta Parvateshvara

- balairudidhibhiriva parchalitsalilaih samantaad uprudham Kusumpurama"

- (Sanskrit original, Mudrarakshasa 2).

- ↑ The Hunas mentioned in Mudrarakshasa play (II) of Vishakhadatta are same people as the Harahunas of the Mahabharata (II.32.12). They were located in Herat/Aria according to Dr Moti Chandra and were an earlier branch of the Hunas (See: Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, p 66, Dr Moti Chandra; Also: Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, 1971, p 33, Dr D. C. Sircar.

- ↑ Radhakumud Mookerji (1988). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (p. 39). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 8120804058.

- ↑ Source:Megasthenes fragment XXVII

- ↑ "Shastri, Nilakantha, "Age of the Nandas and Mauryas," p.165, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1967)

- ↑ Reference: "India: The Ancient Past" p.113, Burjor Avari, Routledge, ISBN 0415356156

- ↑ Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, translation S. Dhammika.

- ↑ Sarat Chandra Roy. 1921. Man in India. Calcutta, etc: A.K. Bose, etc., Item notes: v. 42 1962, p. 279.

- ↑ Jackson, A. V. Williams, Romesh Chunder Dutt, Vincent Arthur Smith, Stanley Lane-Poole, Stanley Lane-Poole, H. M. Elliot, William Wilson Hunter, William Wilson Hunter, Alfred Comyn Lyall, and A. V. Williams Jackson. 1906. History of India (London: Grolier Society), p. 204.

- ↑ Khanna, Vikramaditya S. (2005). The Economic History of the Corporate Form in Ancient India. University of Michigan.

- ↑ Source: "Butkara I," Facenna.

- ↑ "L'age d'or de l'Inde Classique," p23

- ↑ "L'age d'or de l'Inde Classique," p22

- ↑ Rangarajan, M. (2001) India's Wildlife History, pp 7.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Rangarajan, M. (2001) India's Wildlife History, pp 8.

- ↑ Plutarch 62-3. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Justin XV.4.19. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Discussion on the dynastic alliance in Tarn, p152-153: "It has been recently suggested that Asoka was grandson of the Seleucid princess, whom Seleucus gave in marriage to Chandragupta. Should this far-reaching suggestion be well founded, it would not only throw light on the good relations between the Seleucid and Maurya dynasties, but would mean that the Maurya dynasty was descended from, or anyhow connected with, Seleucus... when the Mauryan line became extinct, he (Demetrius) may well have regarded himself, if not as the next heir, at any rate as the heir nearest at hand." Also discussed in "Taxila," John Marshall

- ↑ A similar case is known when Antiochus III fought Euthydemus of Bactria around 210 B.C.E., and finally gave one of his daughters to his son Demetrius: :"And after several journeys of Teleas to and fro between the two, Euthydemus at last sent his son Demetrius to confirm the terms of the treaty. Antiochus received the young prince; and judging from his appearance, conversation, and the dignity of his manners that he was worthy of royal power, he first promised to give him one of his own daughters, and secondly conceded the royal title to his father." Polybius 11.34 Siege of Bactra. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Tarn, John Marshall, "The Cambridge Shorter History of India," by J.Allan, p. 33: "If the usual oriental practice was followed and if we regard Chandragupta as the victor, then it would mean that a daughter or other female relative of Seleucus was given to the Indian ruler or to one of his sons, so that Asoka may have had Greek blood in his veins.." Also McEvilley, "The shape of ancient thought," 2002, p. 367, ISBN 1-58115-203-5: "Asoka may have been either one-half or one-quarter Greek." Ashoka, the son of Bindusara, also happens to have been born around the time this matrimonial alliance was sealed.

- ↑ The unknown Ashoka

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History," Chap. 21

- ↑ Ath. Deip. I.32. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae" XIV.67. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ [1]. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ Polybius 11.39. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ According to the Ashokavadana

- ↑ Sir John Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi," Eastern Book House, 1990, ISBN-10: 8185204322, pg.38

- ↑ E. Lamotte: History of Indian Buddhism, Institut Orientaliste, Louvain-la-Neuve 1988 (1958)

- ↑ Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas by Romila Thapar, Oxford University Press, 1960 P200

See also

Template:Ancient history

- Dhangar

- Mauryan art

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Robert Morkot, The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Greece ISBN 0140513353

- Chanakya, Arthashastra ISBN 0140446036

- J.F.C. Fuller, The Generalship of Alexander the Great ISBN 0306813300

External links

- The Mauryan Empire at All Empires

- Livius.org: Maurya dynasty

- Mauryan Empire of India

- Extent of the Empire

- The Mauryan Empire from Britannica

- Ashoka and Buddhism

- Ashoka's Edicts

| Preceded by: Nanda Dynasty |

Magadha dynasties |

Succeeded by: Sunga dynasty |

| |||||||||||

| Middle kingdoms of India | ||||||||||||

| Timeline: | Northern Empires | Southern Dynasties | Northwestern Kingdoms | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6th century B.C.E. |

|

|

(Persian rule)

(Islamic empires) | |||||||||

[[Category:]]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.