Insect

| Insects | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Honeybee (order Hymenoptera) | ||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Classes & Orders | ||||||||

|

Subclass: Apterygota

Subclass: Pterygota

|

Note: This is only a rough draft, with notes. Please do not edit this article until the final draft is complete — i.e., when this notice is removed. You may add comments on what you would like to see included in the discussion area.Rick Swarts 19:47, 22 December 2005 (UTC)

Insects are invertebrate animals of the Class Insecta, the largest and (on land) most widely distributed taxon within the Phylum Arthropoda. Insects comprise the most diverse group of animals on the earth, with over 800,000 species described—more than all other animal groups combined: "Indeed, in no one of her works has Nature more fully displayed her exhaustless ingenuity," Pliny exclaimed. Insects may be found in nearly all environments on the planet, although only a small number of species have adapted to life in the oceans where crustaceans tend to predominate. There are approximately 5,000 dragonfly species, 2,000 praying mantis, 20,000 grasshopper, 170,000 butterfly and moth, 120,000 fly, 82,000 true bug, 350,000 beetle, and 110,000 bee and ant species. Estimates of the total number of current species, including those not yet known to science, range from two to thirty million, with most authorities favoring a figure midway between these extremes. The study of insects is called entomology.

Relationship to other arthropods

A few smaller groups with similar body plans, such as springtails (Collembola), are united with the insects in the Subphylum Hexapoda. The true insects (that is, species classified in the Class Insecta) are distinguished from all other arthropods in part by having ectognathous, or exposed, mouthparts and eleven (11) abdominal segments. Most species, but by no means all, have wings as adults. Terrestrial arthropods, such as centipedes, millipedes, scorpions and spiders, are sometimes confused with insects due to the fact that both have similar body plans, sharing (as do all arthropods) a jointed exoskeleton.

Morphology and development

Insects range in size from less than a millimeter to over 18 centimeters (some walkingsticks) in length. Insects possess segmented bodies supported by an exoskeleton, a hard outer covering made mostly of chitin. The body is divided into a head, a thorax, and an abdomen. The head supports a pair of sensory antennae, a pair of compound eyes, and a mouth. The thorax has six legs (one pair per segment) and wings (if present in the species). The abdomen has excretory and reproductive structures.

Insects have a complete digestive system. That is, their digestive system consists basically of a tube that runs from mouth to anus, contrasting with the incomplete digestive systems found in many simpler invertebrates. The excretory system consists of Malpighian tubules for the removal of nitrogenous wastes and the hindgut for osmoregulation. At the end of the hindgut, insects are able to reabsorb water along with potassium and sodium ions. Therefore, insects don't usually excrete water with their feces, a fact which allows them to store water in the body. This process of reabsorption enables them to withstand hot, dry environments.

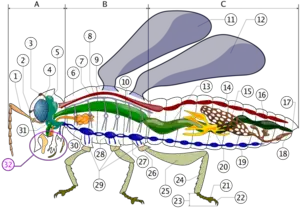

A- Head B- Thorax C- Abdomen

1. antenna

2. ocelli (lower)

3. ocelli (upper)

4. compound eye

5. brain (cerebral ganglia)

6. prothorax

7. dorsal artery

8. tracheal tubes (trunk with spiracle)

9. mesothorax

10. metathorax

11. first wing

12. second wing

13. mid-gut (stomach)

14. heart

15. ovary

16. hind-gut (intestine, rectum & anus)

17. anus

18. vagina

19. nerve chord (abdominal ganglia)

20. Malpighian tubes

21. pillow

22. claws

23. tarsus

24. tibia

25. femur

26. trochanter

27. fore-gut (crop, gizzard)

28. thoracic ganglion

29. coxa

30. salivary gland

31. subesophageal ganglion

32. mouthparts

Most insects have two pairs of wings located on the second and third thoracic segments. Insects are the only invertebrate group to have developed flight, and this has played an important part in their success. The winged insects, and their secondarily wingless relatives, make up the subclass Pterygota. Insect flight is not very well understood, relying heavily on turbulent atmospheric effects. In more primitive insects it tends to rely heavily on direct flight muscles, which act upon the wing structure. More advanced flyers, which make up the Neoptera, generally have wings that can be folded over their back, keeping them out of the way when not in use. In these insects, the wings are powered mainly by indirect flight muscles that move the wings by stressing the thorax wall. These muscles are able to contract when stretched without nervous impulses, allowing the wings to beat much faster than would be otherwise possible.

Insects use tracheal respiration in order to transport oxygen through their bodies. Openings on the surface of the body called spiracles lead to the tubular tracheal system. Air reaches internal tissues via this system of branching trachea. The circulatory system of insects, like that of other arthropods, is open: the heart pumps the hemolymph through arteries to open spaces surrounding the internal organs; when the heart relaxes, the hemolymph seeps back into the heart.

Insects hatch from eggs, and undergo a series of moults as they develop and grow in size. This manner of growth is necessitated by the exoskeleton. Moulting is a process by which the individual escapes the confines of the exoskeleton in order to increase in size, then grows a new outer covering. In most types of insects, the young, called nymphs, are basically similar in form to the adults (an example is the grasshopper), though wings are not developed until the adult stage. This is called incomplete metamorphosis. Complete metamorphosis distinguishes the Endopterygota, which includes many of the most successful insect groups. In these species, an egg hatches to produce a larva, which is generally worm-like in form. The larva grows and eventually becomes a pupa, a stage sealed within a cocoon or chrysalis in some species. In the pupal stage, the insect undergoes considerable change in form to emerge as an adult, or imago. Butterflies are an example of an insect that undergoes complete metamorphosis.

Behavior

Many insects possess very refined organs of perception. In some cases, their senses can be more capable than humans. For example, bees can see in the ultraviolet spectrum, and male moths have a specialized sense of smell that enables them to detect the pheromones of female moths over distances of many kilometers.

Social insects, such as the ant and the bee, are the most familiar species of eusocial animal. They live together in large well-organized colonies that are so tightly integrated and genetically similar the colonies are sometimes considered superorganisms.

Roles in the environment and human society

Many insects are considered pests by humans, because they transmit diseases (mosquitos, flies), damage structures (termites), or destroy agricultural goods (locusts, weevils). Many entomologists are involved in various forms of pest control, often using insecticides, but more and more relying on methods of biocontrol.

Although pest insects attract the most attention, many insects are beneficial to the environment and to humans. Some pollinate flowering plants (for example wasps, bees, butterflies, ants). Pollination is a trade between plants which need to reproduce, and pollinators which receive rewards of nectar and pollen. A serious environmental problem today is the decline of populations of pollinator insects, and a number of species of insects are now cultured primarily for pollination management in order to have sufficient pollinators in the field, orchard or greenhouse at bloom time.

Insects also produce useful substances such as honey, wax, lacquer or silk. Honeybees, (pictured above) have been cultured by humans for thousands of years for honey, although contracting for crop pollination is becoming more significant for beekeepers. The silkworm has greatly affected human history as silk-driven trade established relationships between China and the rest of the world. Fly larvae (maggots) were formerly used to treat wounds to prevent or stop gangrene, as they would only consume dead flesh. This treatment is finding modern usage in some hospitals. Insect larvae of various kinds are also commonly used as fishing bait.

In some parts of the world, insects are used for human food ("Entomophagy"), while being a taboo in other places. There are proponents of developing this use to provide a major source of protein in human nutrition. Since it is impossible to entirely eliminate pest insects from the human food chain, insects already are present in many foods, especially grains. Most people do not realize that food laws in many countries do not prohibit insect parts in food, but rather limit the quantity. According to cultural materialist anthropologist Marvin Harris, the eating of insects is taboo in cultures that have protein sources that require less work like farm birds or cattle.

Many insects, especially beetles, are scavengers, feeding on dead animals and fallen trees, recycling the biological materials into forms found useful by other organisms. The ancient Egyptian religion adored beetles and represented them as scarabeums.

Although mostly unnoticed by most humans, arguably the most useful of all insects are insectivores, those that feed on other insects. Many insects, such as grasshoppers can potentially reproduce so fast that they could literally bury the earth in a single season. However there are hundreds of other insect species that feed on grasshopper eggs, and some that feed on grasshopper adults. This role in ecology is usually assumed to be primarily one of birds, but insects, though less glamorous, are much more significant. For any pest insect one can name, there is a species of wasp that is either a parasitoid or predator upon that pest, and plays a significant role in controlling it.

Human attempts to control pests by insecticides can backfire, because important but unrecognized insects already helping to control pest populations are also killed by the poison, leading eventually to population explosions of the pest species.

Fossils and evolution

The relationships of insects are unclear. Although traditionally grouped with millipedes and centipedes, evidence has emerged favoring a relationship with the crustaceans.

Apart from some tantalizing Devonian fragments, insects first appear suddenly in the fossil record during the very start of the Late Carboniferous period, Early Bashkirian age, about 350 million years ago. As they are already specialized, and represented by more than half a dozen different orders, their anscestry must be sought earlier the Carboniferous, if not the Devonian.

Little is known about the origin of insect flight, since the earliest winged insects appear to be capable fliers. Wings themselves are now thought to be highly modified gills, and some insects (e.g. the Palaeodictyoptera) had an additional pair of winglets attaching to the first segment of the thorax, for a total of three pairs.

Late Carboniferous and Early Permian insect orders include both several current very long-lived groups (mayflies, (Ephemeroptera), dragonflies (Odonata), cockroaches (Blattodea), and Orthoptera (grasshoppers and their relatives)) and a number of Paleozoic forms. During this time, some giant dragonfly-like forms - e.g. Meganeura and Meganeuropsis (Order Protodonata) and Mazothairos (Order Palaeodictyoptera) - reached wingspans of 55 to 70 cm, making them far larger than any living insect.

The Permian, around 270 million years, saw the development of most extant orders; while many of the early groups became extinct during the Permian-Triassic extinction event, the largest mass extinction in the history of the earth.

The remarkably successful Hymenopterans appeared in the Cretaceous but achieved their diversity more recently, in the Cenozoic. A number of highly successful insect groups — especially the Hymenoptera and Lepidoptera (butterflies), as well as many types of Diptera (flies) and Coleoptera (beetles) — evolved in conjunction with flowering plants, a powerful illustration of co-evolution.

Many modern insect genera developed during the Cenozoic; from this period on we find insects preserved in amber, often in perfect condition and easily compared with modern species. The study of fossilized insects is called paleoentomology.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Triplehorn, Charles A. and Norman F. Johnson (2005-05-19). Borror and DeLong's Introduction to the Study of Insects. Thomas Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0030968356. — a classic textbook in North America

- Grimaldi, David and Michael S. Engel (2005-05-16). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521821495. — an up to date review of the evolutionary history of the insects

Quotes

- "Something in the insect seems to be alien to the habits, morals, and psychology of this world, as if it had come from some other planet: more monstrous, more energetic, more insensate, more atrocious, more infernal than our own."

- —Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949)

See also

Cleanly flesh-fly, 4:05 minute film - 8MB xvid in ogg container showing a flesh-fly using its front and back pairs of legs to clean wings and head. The film runs at half speed to enable the viewer to appreciate the fast movements of the animal.

- Animal

- Invertebrate

- Prehistoric insect

- Insect flight

External links

- Bug Bytes A reference library of digitized insect sounds.

- Entomological Links A long list of links about insects

- INSECTS .org A shameless promotion of insect appreciation.

- Insects as Food by Gene DeFoliart. Information about insects as a food resource.

- Kendall Bioresearch Bug Index, Featured Bugs, Classification, ID, Fossils, Body-parts, Micro Views, Life Cycles, Pesticide Safety.

- Meganeura Website about insect evolution and fossil record.

- Tree of Life Project – Insecta

- UF Book of Insect Records, documenting "insect champions" in different categories

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.