Hawaii

Template:US state

Hawaii, pronounced “ha-wai-ee,” is the only U.S. state that is completely surrounded by water, is the only state that continues to grow in area because of active extrusive lava flows, and has more endangered species per square mile than anywhere else.

This archipelago represents the exposed peaks of a great undersea mountain range known as the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, formed by volcanic activity over a hotspot in the earth's mantle. At about 3000 km (1860 miles) from the nearest continent, the Hawaiian Island archipelago is the most isolated grouping of islands on Earth.

Geography

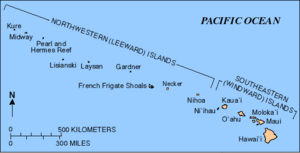

The Hawaiian Islands, once known as the Sandwich Islands, form an archipelago of nineteen islands and atolls, numerous smaller islets, and undersea seamounts trending northwest by southeast in the North Pacific Ocean between latitudes 19°N and 29°N. The archipelago takes its name from the largest island in the group and extends some 1500 miles (2400 km) from the Island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kure Atoll.

Of these, eight high islands are considered the "main islands" and are located at the southeastern end of the archipelago. These islands are, in order from the northwest to southeast, Niihau, Kauai, Oahu, Molokai, Lānai, Kahoolawe, Maui and the Island of Hawaii.

All of the Hawaiian Islands were formed by volcanoes arising from the sea floor through a vent described in geological theory as a hotspot. The theory maintains that as the tectonic plate beneath much of the Pacific Ocean moves in a northwesterly direction, the hot spot remains stationary, slowly creating new volcanoes. This explains why only volcanoes on the southern half of the Island of Hawaii are presently active.

The last volcanic eruption outside the Island of Hawaii happened at Haleakalā on Maui in the late 18th century. The newest volcano to form is Lōihi, deep below the waters off the southern coast of the Island of Hawaii.

The islands are the farthest removed from any other body of land in the world. The isolation of the Hawaiian Islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and the wide range of environments to be found on high islands located in and near the tropics, has resulted in a vast array of endemic flora and fauna, with a considerable number found exclusively in Hawaii or the surrounding ocean. Because of the islands' volcanic formation, native life before human activity is said to have arrived by the "3 W's": wind, waves, and wings. The volcanic activity and subsequent erosion created impressive geological features.

Hawaii is notable for rainfall: Mount Waialeale, on the island of Kauai, has the second highest average annual rainfall on earth: about 460 inches (11.7 m). The Big Island of Hawaii is notable as the world's fifth highest island. If the height of the island is measured from its base, deep in the ocean, to its snow-clad peak on Mauna Kea, it can be considered one of the tallest mountains in the world.

The climate of Hawaii is atypical for a tropical area, and is regarded as more subtropical than the latitude would suggest, because of the moderating effect of the surrounding ocean. Temperatures and humidity tend to be less extreme, with summer high temperatures seldom reaching above the upper 80s (°F) and winter temperatures (at low elevation) seldom dipping below the mid-60s. Snow, although not usually associated with tropics, falls at high elevations on Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the Big Island in some winter months. Snow only rarely falls on Maui's Haleakalā.

Local climates vary considerably on each island, grossly divisible into windward (koolau) and leeward (ewa) areas based upon location relative to the higher mountains. Windward sides face the northeast trades and receive much more rainfall; leeward sides are drier, with less rain and less cloud cover. This fact is utilized by the tourist industry, which concentrates resorts on sunny leeward coasts.

History

- Main article: History of Hawaiʻi

Hawaiian antiquity

- Main articles: Ancient Hawaii, Hawaiian mythology, Polynesian mythology

Anthropologists believe that Polynesians from the Marquesas and Society Islands first populated the Hawaiian Islands at some time after AD 300-500, although recent evidence has pointed to an initial settlement of as late as AD 800-1000. It is not resolved whether there was only one extended or two isolated periods of settlement. The latter view of an initial Marquesan settlement, followed by isolation and Tahitian settlers in approximately AD 1300 who conquered and eliminated the original inhabitants of the islands, is hinted at in folk tales, like the stories of Hawaiʻiloa, Paʻao and menehune. More recently, the theory that there was only one extended period during which groups of immigrants repeatedly arrived and contact with their former homelands was not lost until the early 2nd millennium AD has become more accepted among some scientists, as direct evidence for a massive conquest and a sudden replacement of cultural practices has not been found in the archaeological record.

Voyaging between Hawaiʻi and the South Pacific apparently ceased with no explanation several centuries before the arrival of the Europeans (although at that time, there seems to have been a general decline in overseas trade and voyaging across Polynesia; see Henderson Island). Local chiefs, called aliʻi, ruled their settlements and fought to extend their sway and defend their communities from predatory rivals. Warfare was endemic. The general trend was toward chiefdoms of increasing size, even encompassing whole islands.

Vague reports by various European explorers suggest that Hawaiʻi was visited by foreigners well before the 1778 arrival of British explorer Captain James Cook. Historians credited Cook with the discovery after he was the first to plot and publish the geographical coordinates of the Hawaiian Islands. Cook named his discovery the Sandwich Islands in honor of one of his sponsors, John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich.

Hawaiian kingdom

- Main article: Kingdom of Hawaiʻi

After a series of battles that ended in 1795 and peaceful cession of the island of Kauaʻi in 1810, the Hawaiian Islands were united for the first time under a single ruler who would become known as King Kamehameha the Great. He established the House of Kamehameha, a dynasty that ruled over the kingdom until 1872. One of the most important events during those years was the suppression of the Hawaiʻi Catholic Church.

That led to the Edict of Toleration that established religious freedom in the Hawaiian Islands. The death of the bachelor King Kamehameha V—who did not name an heir—resulted in the election of King Lunalilo. After him, governance was passed on to the House of Kalākaua.

In 1887, citing maladministration, a group of American and European businessmen already involved in Hawaiian government forced King Kalākaua to sign the Bayonet Constitution which not only stripped the king of administrative authority but eliminated voting rights for Asians and set minimum income and property requirements for American, European and native Hawaiian voters, essentially limiting the electorate to wealthy elite Americans, Europeans and native Hawaiians. King Kalākaua reigned until his death in 1891.

His sister, Liliʻuokalani, succeeded him to the throne and ruled until her dethronement in 1893. Her overthrow, by a coup d'état orchestrated by American and European businessmen, was sparked by the queen's threat to abrogate the constitution. Even though she backed down at the last moment, members of the expatriate community formed a Committee of Safety which mounted a nearly bloodless coup and established a provisional government. On May 30, 1894 a constitutional convention drafted a constitution for a Republic of Hawaiʻi. The Republic was declared on July 4, 1894.

During the kingdom era and subsequent republican regime, ʻIolani Palace — the only official royal residence in the United States today — served as the capitol buildings.

- Kamehamehaii.jpg

Kamehameha II

- Kamehamehaiii.jpg

Kamehameha III

- Kamehameha IV.jpg

Kamehameha IV

- Kamehamehav.jpg

Kamehameha V

- Williamcharleslunalilo.jpg

Lunalilo

- Kalakauapainting.jpg

Kalākaua

Hawaiian territory

- Main article: Territory of Hawaiʻi

When William McKinley won the presidential election in November of 1896, the question of Hawaiʻi's annexation to the U.S. was again opened. The previous president, Grover Cleveland, was a friend of Queen Liliʻuokalani. He had remained opposed to annexation until the end of his term, but McKinley was open to persuasion by U.S. expansionists and by annexationists from Hawaiʻi. He agreed to meet with a committee of annexationists from Hawaiʻi, Lorrin Thurston, Francis Hatch and William Kinney. After negotiations, in June of 1897, McKinley signed a treaty of annexation with these representatives of the Republic of Hawaiʻi. The president then submitted the treaty to the U.S. Senate for approval.

Despite some opposition in the islands, the Newlands Resolution was passed by the House June 15, 1898, by a vote of 209 to 91, and by the Senate on July 6, 1898, by a vote of 42 to 21, formally annexing Hawaiʻi as a U.S. territory in spite of opposition in the Congress (Schamel, Wynell and Charles E. Schamel, 1999)[1][2]. Although its legality was questioned by some because it was a resolution, not a treaty, both houses of Congress carried the measure with two-thirds majorities, whereas a treaty would have only required two-thirds of the Senate vote (Article II, Sec. 2, U.S. Constitution).

The overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and the subsequent annexation of Hawaiʻi are sometimes cited as examples of American imperialism.

In 1900, it was granted self-governance and retained ʻIolani Palace as the territorial capitol building. Though several attempts were made to achieve statehood, Hawaiʻi remained a territory for sixty years. Plantation owners, like those who comprised the so-called Big Five, found territorial status convenient, enabling them to continue importing cheap foreign labor; such immigration was prohibited in various other states of the Union.

The power of the plantation owners was finally broken by activist descendants of original immigrant laborers. Because they were born in a U.S. territory, they were legal U.S. citizens. Expecting to gain full voting rights, they actively campaigned for statehood for the Hawaiian Islands.

Hawaiian statehood

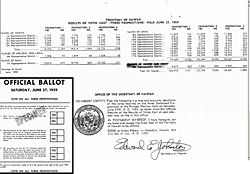

In March 1959, both houses of Congress passed the Admission Act and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed it into law. (The act excluded Palmyra Atoll, part of the Kingdom and Territory of Hawaiʻi, from the new state.) On June 27 of that year, a plebiscite was held asking residents of Hawaiʻi to vote on accepting the statehood bill. Hawaiʻi voted 17 to 1 to accept. On August 21, church bells throughout Honolulu were rung upon the proclamation that Hawaiʻi was the 50th state of the Union.

After statehood, Hawaiʻi quickly became a modern state with a construction boom and rapidly growing economy. The Hawaiʻi Republican Party, which was strongly supported by the plantation owners, was voted out of office. In its place, the Democratic Party of Hawaiʻi dominated state politics for forty years.

In recent decades, the state government has implemented programs to promote Hawaiian culture. The Hawaiʻi State Constitutional Convention of 1978 incorporated as state constitutional law specific programs such as the creation of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs to promote the indigenous Hawaiian language and culture.

Controversy has erupted within the last decade over the extent of the Hawaiian cultural programs creating a new political dialogue within the state. Pitting the strong emotions of both integrationists and separatists, high rhetoric has been employed by both groups including the use of propaganda materials of dubious provenance. A much criticized example includes the Hui Aloha ʻAina and Hui Kalaiʻaina petitions allegedly rediscovered in 1998. According to their proponents, the petitions are contemporaneous to the annexation of Hawai'i with one petition purportedly containing 22,000 signatures in opposition to the annexation while a second petition purportedly contains 17,000 signatures in favor of reinstating the monarchy. The validity of the petitions has been criticized by Lorrin Thurston in an analysis which indicates significant fraud.

Demographics

| Census year |

Population |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 154,001 |

| 1910 | 191,874 |

| 1920 | 255,881 |

| 1930 | 368,300 |

| 1940 | 422,770 |

| 1950 | 499,794 |

| 1960 | 632,772 |

| 1970 | 769,913 |

| 1980 | 964,691 |

| 1990 | 1,108,229 |

| 2000 | 1,211,537 |

As of 2005, Hawaii has an estimated population of 1,275,194, which is an increase of 13,070, or 1.0%, from the prior year and an increase of 63,657, or 5.3%, since the year 2000. This includes a natural increase since the last census of 48,111 people (that is 96,028 births minus 47,917 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 16,956 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 30,068 people, and migration within the country produced a net loss of 13,112 people.

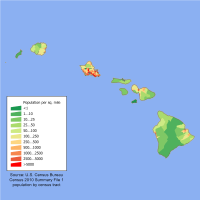

Hawaiʻi has a de facto population of over 1.3 million due to military presence and tourists. Oʻahu, which is aptly nicknamed "The Gathering Place", is the most populous island (and the one with the highest population density), with a resident population of just under one million.

Ethnically, Hawaiʻi is the only state that has a majority group that is non-white (and one of only four in which non-Hispanic whites do not form a majority) and has the largest percentage of Asian Americans.

Hawaii was the first majority-minority state in the United States since the 20th century. According to the 2000 Census, 6.6% of Hawaiʻi's population identified themselves as Native Hawaiian, 24.3% were White American, including Portuguese and 41.6% were Asian American, including 0.1% Asian Indian, 4.7% Chinese, 14.1% Filipino, 16.7% Japanese, 1.9% Korean and 0.6% Vietnamese. 1.3% were other Pacific Islander American, which includes Samoan American, Tongan, Tahitian, Māori and Micronesian, and 21.4% described themselves as mixed (two or more races/ethnic groups). 1.8% were Black or African American and 0.3% were Native American and Alaska Native.

The second group of foreigners to arrive upon Hawaiʻi's shores, after the Europeans, were the Chinese. Chinese employees serving on Western trading ships disembarked and settled starting in 1789. In 1820 the first American missionaries arrived in Hawaiʻi to preach Christianity and teach the Hawaiians what the missionaries considered "civilized" ways. A large proportion of Hawaiʻi's population has become a people of Asian ancestry (especially Chinese, Japanese and Filipino), many of whom are descendants from those waves of early foreign immigrants brought to the islands in the nineteenth century, beginning in the 1850's, to work on the sugar plantations. The first 153 Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaiʻi on June 19, 1868. They were not "legally" approved by the Japanese government established after the Meiji Restoration because the contract was between a broker and the by then terminated Tokugawa shogunate. The first Japanese government-approved immigrants arrived in Hawaiʻi on February 9, 1885 after Kalākaua's petition to Emperor Meiji when Kalākaua visited Japan in 1881)

As of 2000, 73.4% of Hawaiʻi residents age 5 and older speak only English at home and 7.9% speak Pacific Island languages. Tagalog is the third most spoken language at 5.4%, followed by Japanese at 5.0% and Chinese at 2.6%. The official languages are Hawaiian and Hawaiian English. Hawaiian Pidgin is an unofficial language.

- Religion

- See also: Richest Places in Hawaiʻi

Languages

- Main articles: Hawaiian language, Hawaiian English

The state of Hawaiʻi has two official languages as prescribed by the Constitution of Hawaiʻi adopted at the 1978 constitutional convention: Hawaiian and English. Article XV, Section 4 requires the use of Hawaiian in official state business such as public acts, documents, laws and transactions. Standard Hawaiian English, a subset of American English, is also commonly used for other formal business. Hawaiian is legally acceptable in all legal documents, from depositions to legislative bills. The third and fourth most spoken languages are Tagalog and Japanese, respectively.

Origins

Hawaiian is a member of the Polynesian branch of the Austronesian family. It was brought to the islands by Polynesian seafarers, who are thought to have arrived around 1300 C.E.

Before the arrival of Captain James Cook, the Hawaiian language was purely a spoken language. The first written form of Hawaiian was developed by American Protestant missionaries in Hawaiʻi during the early 19th century. The missionaries assigned letters from the English alphabet that roughly corresponded to the Hawaiian sounds. Later, additional characters were added to clarify pronunciation.

Unlike English, Hawaiian is a mora-timed language. This means that it distinguishes between long and short vowels. In the writing system, the long vowels are written with a macron called kahakō. Also unlike English, in Hawaiian, the presence or absence of a glottal stop is distinctive. In writing, a glottal stop is indicated with the ʻokina. When a Hawaiian word is spelled without the necessary ʻokina and kahakō, it is impossible for someone who does not already know the word to guess at the proper pronunciation.

Omission of the ʻokina and kahakō in printed texts can even obscure the meaning of a word. For example, the word lanai means stiff-necked, while lānai means veranda, and Lānaʻi is the name of one of the Hawaiian islands. This can be a problem in interpreting 19th century Hawaiian texts recorded in the older orthography. For these reasons, careful writers now use the modern Hawaiian orthography.

Revival

As a result of the constitutional provision, interest in the Hawaiian language was revived in the late 20th century. Public and independent schools throughout the state began teaching Hawaiian language standards as part of the regular curricula, beginning with preschool. With the help of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, also created by the 1978 constitutional convention, specially designated Hawaiian language immersion schools were established where students would be taught in all subjects using Hawaiian. Also, the University of Hawaiʻi System developed the only Hawaiian language graduate studies program in the world. Municipal codes were altered in favor of Hawaiian place and street names for new civic developments.

Pidgin

Template:Cleanup-date

A majority of citizens in Hawaiʻi currently speak what many linguists refer to as Hawaiian Creole English (HCE). In 1778, Europeans discovered the islands of Hawaiʻi and the 19th century saw a great increase in immigrations from neighboring countries and a Pidgin form of English developed, consisting of varying degrees of English comprehension along with elements of the native Hawaiians' language. By the early 20th century, a Creole English developed. A Creole language is typically considered to be a language derived from Pidgin speakers passing their language to the next generation. As the next generation acquires the pidgin language it becomes solidified and standardized. One interesting trait of the HCE is that it managed to preserve many terms from the original Hawaiian language, even after most natives had died due to a variety of diseases. In Hawaiʻi, modern speakers are likely to include smatterings of Hawaiian words without having those words being considered archaic. Here are some examples of Hawaiian words which are still commonly in use today:

Aloha: this word is generally a courteous greeting; it can have a variety of meanings including connotations of love, affections, kindness, well wishing, and can be used for hello and goodbye. Mahalo: similar to aloha, this word can have many meanings and is generally a showing of gratitude. Typically, it is the equivalent of saying thank you. This word is frequently used after a business interaction is completed. Keiki: this word is a term for a young child, normally one who has not reached the age of reason. Frequently signs will be posted on lawns reading "Keiki at Play", meaning drive slow, children are playing. Haole: This is the Hawaiian word used to refer to Caucasians or foreigners in general. The term suggests classification but is not necessarily derogatory. A person who has one Caucasian parent and one Pacific Islander parent will commonly be referred to as a "Hapa-Haole" (hapa meaning 'half').

Most streets, cities, and towns in Hawaiʻi are named after words from the native language. For example, the large town on Maui called Lāhainā is taken from a Hawaiian phrase meaning "Unmerciful Sun." The first large shopping center was built on Honolulu and named "Ala Moana" (ala=path to, moana=ocean). Also, the names native Hawaiians gave to indigenous wildlife remained the same after foreign influences came to the island. For example, tuna fish are commonly referred to by their Hawaiian name "ahi." Also, many Hawaiian words have found their way into the mainstream American lexicon, such as:

Hula: dance involving gyration of hips Luʻau: festive gathering featuring food and dance Lei: necklace made of flowers strung together Muʻumuʻu: large flowing dress Tiki: image of a deity carved from wood

The HCE as it is generally spoken employs a very lax usage of English grammar. Aspects of language such as articles, prepositions, and proper nouns are frequently dropped if their meaning is understood. For example, instead of saying "It is hot today, isn't it?" an HCE speaker is likely to say simply "Hot, yeah?" HCE speakers also frequently will use English words while changing the meaning and intent of the words. For example, the terms "auntie" and "uncle" can be used to refer to any adult who is a friend or a friend to the family. This terminology creates a very personal sense of community. HCE speakers also have acquired a form of slang in their common speech. There are many phrases used on a daily basis that appear to be original and yet are in some ways derived from English phrases, such as:

Brah: this is a shortening of "Brother" but can refer to any friend or acquaintance. Broke da mout: this literally means "broke the mouth" and is said to imply that a food someone cooked is delicious. Choke: this is used to suggest that there is more than enough of something. Da Kine: this literally means "the kind" but is used as a substitute for a noun when the noun cannot be remembered. For example, a person can point to a cucumber on a table and say "Pass me da kine." Grind: this means to eat a large amount of food quickly. I K sufa: it is hard to translate this term literally, but it essentially is used to empathize with another's misfortune. Lickins: this literally means "lickings" and is used to imply punishment such as spanking to a child. Mo bettah: this essentially means that one thing is better in comparison to something else. Pidgin to da max: this phrase is used to refer to a person who has a very limited understanding of proper English pronunciation and grammar.

Oftentimes tourists, or "haoles", will see HCE speakers as people of lower intelligence. The contrary can be argued; considering how Hawaiʻi has very little in terms of industry (most of its exports are agricultural), the HCE is sufficient for their needs. The population of Hawaiʻi is growing, Honolulu in particular is becoming more urbanized, and there are some who speculate Hawaiʻi will become a technopolis in the near future. If this were to happen, it is then possible for the HCE to be deemed insufficient.

Throughout the surfing boom in Hawaii, HCE has influenced surfing slang. Many HCE words such as Brah, and Da kine have found their way to other places. The usage of "da" instead of "the" is common amongst surfers worldwide.

Debates

A somewhat divisive political issue that has arisen since the Constitution of Hawaiʻi adopted Hawaiian as an official state language is the exact spelling of the state's name. As prescribed in the Admission of Hawaiʻi Act that granted Hawaiian statehood, the federal government recognizes Hawaii to be the official state name. However, many state and municipal entities and officials have recognized Hawaiʻi to be the correct state name, and this is how it is spelled in standard Hawaiian English.

Official government publications, as well as department and office titles, use the traditional Hawaiian spelling. Private entities, including local mass media, also have shown a preference for the use of the ʻokina. While in local Hawaiian society the spelling and pronunciation of Hawaiʻi is preferred in nearly all cases, even by standard English speakers, the federal spelling is used for purposes of interpolitical relations between other states and foreign governments.

The nuances in the Hawaiian language debate are often not obvious or well-appreciated outside Hawaiʻi. The issue has often been a source of friction in situations where correct naming conventions are mandated, as people frequently disagree over which spelling is correct or incorrect, and where it is correctly or incorrectly applied.

Seealso Hawaiian alphabet

Economy

The history of Hawaiʻi can be traced through a succession of dominating industries: sandalwood, whaling, sugarcane, pineapple, military, tourism, and education. Since statehood was achieved in 1959, tourism has been the largest industry in Hawaiʻi, contributing 24.3% of the Gross State Product (GSP) in 1997. New efforts are underway to diversify the economy. The total gross output for the state in 2003 was US$47 billion; per capita income for Hawaiʻi residents was US$30,441.

Industrial exports from Hawaiʻi include food processing and apparel. These industries play a small role in the Hawaiʻi economy, however, due to the considerable shipping distance to markets on the west coast of the United States and ports of Japan. The main agricultural exports are nursery stock and flowers, coffee, macadamia nuts, pineapple, livestock, and sugar cane. Agricultural sales for 2002, according to the Hawaiʻi Agricultural Statistics Service, were US$370.9 million from diversified agriculture, US$100.6 million from pineapple, and US$64.3 million from sugarcane.

Hawaiʻi is known for its relatively high per capita state tax burden. In the years 2002 and 2003, Hawaiʻi residents had the highest state tax per capita at US$2,757 and US$2,838, respectively. This rate can be explained partly by the fact that services such as education, health care and social services are all rendered at the state level — as opposed to the municipal level as all other states.

Millions of tourists contribute to the collection figure by paying the general excise tax and hotel room tax; thus not all the taxes collected come directly from residents. Business leaders, however, have often considered the state's tax burden as being too high, contributing to both higher prices and the perception of an unfriendly business climate [3]. See the list of businesses in Hawaiʻi for more information on commerce in the state.

Until recently, Hawaiʻi was the only state in the U.S. that attempted to control gasoline prices through a Gas Cap Law. The law was enacted during a period when oil profits in Hawaiʻi in relation to the Mainland U.S. were under scrutiny, and sought to tie local gasoline prices to those of the Mainland. The law took effect in September 2005 amid price fluctuations caused by Hurricane Katrina. The Hawaiʻi state legislature suspended the law in April 2006.

Law and government

The state government of Hawaiʻi is modeled after the federal government with adaptations originating from the kingdom era of Hawaiian history. As codified in the Constitution of Hawaiʻi, there are three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial.

The executive branch is led by the Governor of Hawaiʻi and assisted by the Lieutenant Governor of Hawaiʻi, both elected on the same ticket. The governor, in residence at Washington Place, is the only public official elected for the state government in a statewide race; all other administrators and judges are appointed by the governor. The lieutenant governor is concurrently the Secretary of State of Hawaiʻi. Both the governor and lieutenant governor administer their duties from the Hawaiʻi State Capitol. The governor and lieutenant governor oversee the major agencies and departments of the executive of which there are twenty.

The legislative branch consists of the Hawaiʻi State Legislature — the twenty-five members of the Hawaiʻi State Senate led by the President of the Senate and the fifty-one members of the Hawaiʻi State House of Representatives led by the Speaker of the House. They also govern from the Hawaiʻi State Capitol. The judicial branch is led by the highest state court, the Hawaiʻi State Supreme Court, which uses Aliʻiolani Hale as its chambers. Lower courts are organized as the Hawaiʻi State Judiciary.

The state is represented in the Congress of the United States by a delegation of four members. They are the senior and junior United States Senators, the representative of the First Congressional District of Hawaiʻi and the representative of the Second Congressional District of Hawaiʻi. Many Hawaiʻi residents have been appointed to administer other agencies and departments of the federal government by the President of the United States. All federal officers of Hawaiʻi administer their duties locally from the Prince Kūhiō Federal Building near the Aloha Tower and Honolulu Harbor.

Hawaiʻi is primarily dominated by the Democratic Party and has supported Democrats in 10 of the 12 presidential elections in which it has participated. In 2004, John Kerry won the state's 4 electoral votes by a margin of 9 percentage points with 54% of the vote. Every county in the state supported the Democratic candidate.

The Prince Kūhiō Federal Building also houses agencies of the federal government such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Internal Revenue Service and the United States Secret Service. The building is the site of the federal courts and the offices of the United States Attorney for the District of Hawaiʻi, principal law enforcement officer of the United States Department of Justice in the United States District Court for the District of Hawaiʻi.

- Lindalingle.jpg

Linda Lingle

Governor

(Republican) - Jamesaiona.jpg

James R. Aiona, Jr.

Lieutenant Governor

(Republican) - Daniel Inouye.jpg

Daniel Inouye

U.S. Senator

(Democrat) - Daniel Akaka.jpg

Daniel Akaka

U.S. Senator

(Democrat) - Neilabercrombie.jpg

Neil Abercrombie

U.S. Representative

(Democrat) - Edcaseofficial.jpg

Edward Case

U.S. Representative

(Democrat) - Mayorharrykim.jpg

Harry Kim

Mayor of Hawaiʻi

(Nonpartisan) - Mufi Hannemann 01 cropped.jpg

Mufi Hannemann

Mayor of Honolulu

(Nonpartisan) - Mayoralanarakawa.jpg

Alan Arakawa

Mayor of Maui

(Nonpartisan)

Unique to Hawaiʻi is the way it has organized its municipal governments. There are no incorporated cities in Hawaiʻi except the City & County of Honolulu. All other municipal governments are administered at the county level. The county executives are the Mayor of Hawaiʻi, Mayor of Honolulu, Mayor of Kauaʻi and Mayor of Maui. All mayors in the state are elected in nonpartisan races.

The officers of the federal and state governments have been historically elected from the Democratic Party of Hawaiʻi and the Hawaiʻi Republican Party. Municipal charters in the state have declared all mayors to be elected in nonpartisan races.

See also : United States presidential election, 2004, in Hawaii

Important cities and towns

The movement of the Hawaiian royal family from the Island of Hawaiʻi to Maui and subsequently to Oʻahu explains why certain population centers exist where they do today. The largest city, Honolulu, was the one chosen by King Kamehameha III as the capital of his kingdom because of the natural harbor there, the present-day Honolulu Harbor.

The largest city is the capital, Honolulu, located along the southeast coast of the island of Oʻahu. Other populous cities include Hilo, Kāneʻohe, Kailua, Pearl City, Kahului, Kailua-Kona, Kihei, and Līhuʻe.

Education

- Main article: Hawaiʻi State Department of Education

Hawaiʻi is currently the only state in the union with a unified school system statewide. It is also the oldest public education system west of the Mississippi River. Policy decisions are made by the fourteen-member state Board of Education, with thirteen members elected for four-year terms and one non-voting student member. The Board of Education sets statewide educational policy and hires the state superintendent of schools, who oversees the operations of the state Department of Education. The Department of Education is also divided into seven districts, four on Oʻahu and one for each of the other counties.

The structure of the state Department of Education has been a subject of discussion and controversy in recent years. The main rationale for the current centralized model is equity in school funding and distribution of resources: leveling out inequalities that would exist between highly populated Oʻahu and the more rural Neighbor Islands, and between lower-income and more affluent areas of the state. This system of school funding differs from many localities in the United States where schools are funded from local property taxes.

Policy initiatives have been made in recent years toward decentralization. Current Governor Linda Lingle is a proponent of replacing the current statewide board with seven elected district boards. The Democrat-controlled state legislature opposed her proposal, instead favoring expansion of decision-making power to the schools and giving schools more discretion over budgeting. Political debate of structural reform is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Schools and academies

As stated earlier in the article, the Hawaiʻi State Department of Education operates all of the public schools in the state of Hawaiʻi.

Hawaiʻi has the distinction of educating more students in independent institutions of secondary education than any other state in the United States. It also has four of the largest independent schools: Mid-Pacific Institute, ʻIolani School, Kamehameha Schools, and Punahou School. The second Buddhist high school in the United States, and first Buddhist high school in Hawaiʻi, Pacific Buddhist Academy, was founded in 2003. (The first Buddhist high school in the United States was Developing Virtue Secondary School founded in 1981 in Ukiah, California.)

Other popular independent schools include Hawaiʻi Baptist Academy, Hawaiʻi Preparatory Academy, Maryknoll School, St. Andrew's Priory, and Saint Louis School.

Both independent and charter schools can select their students, while the regular public schools must take all students in their district. For a comprehensive list of independent schools, see the list of independent schools in Hawaiʻi. For a comprehensive list of public schools, see the list of public schools in Hawaiʻi.

Colleges and universities

Graduates of institutions of secondary learning in Hawaiʻi often either enter directly into the work force or attend colleges and universities. While many choose to attend colleges and universities on the mainland or elsewhere, most choose to attend one of many institutions of higher learning in Hawaiʻi.

The largest of these institutions is the University of Hawaiʻi System. It consists of the flagship research university at Manoa, two comprehensive campuses Hilo and West Oʻahu, and 7 Community Colleges. Students choosing private education attend Brigham Young University Hawaiʻi, Chaminade University of Honolulu, Hawaiʻi Pacific University and University of the Nations.

The Saint Stephen Diocesan Center is a seminary of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu. For a comprehensive list of colleges and universities, see the list of colleges and universities in Hawaiʻi.

Problems

Public schools in Hawaiʻi have to deal with large populations of children of non-native English speaking immigrants and a culture that is different in many ways from mainland U.S., from whence most of the course materials come and where most of the standards for schools are set.

The public elementary, middle, and high school scores in Hawaiʻi tend to be below average on national tests as mandated under the No Child Left Behind Act. Some of this can be attributed to the Hawaiʻi State Board of Education requiring all eligible students to take these tests and reporting all student test scores unlike, for example, Texas and Michigan. Results reported in August 2005 indicate that two-thirds of Hawaiʻi's schools failed to reach federal minimum performance standards in math and reading (of 282 schools across the state, 185 failed [4]).

On the other hand, results of the ACT college placement tests show that Hawaiʻi class of 2005 seniors scored slightly above the national average (21.9 compared with 20.9) (Honolulu Advertiser, Aug. 17, 2005, p. B1). It should be noted that fewer students take the ACT examination than take the more widely accepted SAT examination. On the SAT Hawaiʻi's college bound seniors tend to score below the national average in all categories except math.

Hawaiʻi, like all other states in the United States, is struggling to provide educational services in its public schools with shrinking budgets.[citation needed]

Miscellaneous topics

Symbols

The state constitution and various other measures of the Hawaiʻi State Legislature established official symbols meant to embody the distinctive culture and heritage of Hawaiʻi. These include a state bird, state flower, state gem, state mammal, and state tree. The humuhumunukunukuāpuaʻa or reef triggerfish was the state fish, but in 1990, the authorizing legislation was found to have expired. The humuhumunukunukuāpuaʻa was reinstated as the state fish on May 2, 2006.

Included are the two statues representing Hawaiʻi in the United States Capitol; those of King Kamehameha I and Father Damien.

The primary symbol is the state flag, Ka Hae Hawaiʻi, influenced by the British Union Flag and features eight horizontal stripes representing the eight major Hawaiian Islands. The constitution declares the state motto to be Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono, a pronouncement of King Kamehameha III meaning, "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness." It was also the motto of the kingdom, republic and territory. The state song is Hawaiʻi ponoʻī, written by King Kalākaua and composed by Henri Berger. Hawaiʻi Aloha is the unofficial state song, often sung in official state events.

- Nene.neck.arp.600pix.jpg

Hawaiian goose

Nēnē

State Bird - Humuhumunukunukuapuaa.jpg

Reef triggerfish

Humuhumunukunuku-

āpuaʻa

State Fish - Maohauhele.jpg

Hawaiian hibiscus

Maʻo hau hele

State Flower - Aleuritesmoluccana1web.jpg

Candlenut

Kukuʻi

State Tree - Fatherdamienstatue2.jpg

Father Damien Statue

State Capitol

Media

Newspapers

Two major competing Honolulu-based newspapers serve all of Hawaiʻi. The Honolulu Advertiser is owned by Gannett Pacific Corporation while the Honolulu Star-Bulletin is owned by Black Press of British Columbia in Canada. Both are among the largest newspapers in the United States in terms of circulation. Other locally published newspapers are available to residents of the various islands.

The Hawaiʻi business community is served by the Pacific Business News and Hawaiʻi Business Magazine. The largest religious community in Hawaiʻi is served by the Hawaiʻi Catholic Herald. Honolulu Magazine is a popular magazine that offers local interest news and feature articles.

Apart from the mainstream press, the state also enjoys a vibrant ethnic publication presence with newspapers for the Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean and Native Hawaiian communities. In addition, there is an alternative weekly, the Honolulu Weekly.

Television

All the major television networks are represented in Hawaiʻi through KFVE (WB network affiliate), KGMB (CBS network affiliate), KHET (PBS network affiliate), KHNL (NBC network affiliate), KHON (Fox network affiliate), KIKU (UPN network affiliate) and KITV (ABC network affiliate), among others. From Honolulu, programming at these stations is rebroadcast to the various other islands via networks of satellite transmitters. Until the advent of satellite, most network programming was broadcast a week behind mainland scheduling.

The various production companies that work with the major networks have produced television series and other projects in Hawaiʻi. Most notable were police dramas like Magnum P.I. and Hawaii Five-O. Currently, the hit TV show Lost is filmed in the Hawaiian Islands. A comprehensive list of such projects can be seen at the list of Hawaiʻi television series.

Film

Hawaiʻi has a growing film industry administered by the state through the Hawaiʻi Film Office. Several television shows, movies and various other media projects were produced in the Hawaiian Islands, taking advantage of the natural scenic landscapes as backdrops. Notable films produced in Hawaiʻi or were inspired by Hawaiʻi include Hawaii, Blue Hawaii, Donovan's Reef, From Here to Eternity, South Pacific, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lost, Jurassic Park, Outbreak, Waterworld, Six Days Seven Nights, George of the Jungle, 50 First Dates, Pearl Harbor, Blue Crush, and Lilo and Stitch. The upcoming film Snakes on a Plane takes place on an airline bound for Hawaii. Hawaiʻi is home to a prominent film festival known as the Hawaiʻi International Film Festival.

Culture

- Main article: Culture of Hawaiʻi

The aboriginal culture of Hawaiʻi is Polynesian. Hawaiʻi represents the northernmost extension of the vast Polynesian triangle of the south and central Pacific Ocean. While traditional Hawaiian culture remains only as vestiges influencing modern Hawaiian society, there are reenactments of ancient ceremonies and traditions throughout the islands. Some of these cultural influences are strong enough to have affected the culture of the United States at large, including the popularity (in greatly modified form) of luʻaus and hula.

- Customs and etiquette in Hawaiʻi

- Folklore in Hawaiʻi

- Hawaiian mythology

- List of Hawaiʻi state parks

- List of Hawaiʻi State Landmarks

- List of Hawaiʻi-related topics

- Literature in Hawaiʻi

- Music of Hawaiʻi

- Polynesian mythology

- Tourism of Hawaiʻi

Sister states

Hawaiʻi has an active sister state program, which includes ties to:

Azores, Portugal (1982)

Azores, Portugal (1982) Cebu, Philippines (1996)

Cebu, Philippines (1996) Cheju Province, South Korea (1986)

Cheju Province, South Korea (1986) Ehime, Japan (2003)

Ehime, Japan (2003) Fukuoka, Japan (1981)

Fukuoka, Japan (1981) Guangdong, China (1985)

Guangdong, China (1985) Hainan, China (1992)

Hainan, China (1992) Hiroshima, Japan (1997)

Hiroshima, Japan (1997) Ilocos Norte, Philippines (2005)

Ilocos Norte, Philippines (2005) Ilocos Sur, Philippines (1985)

Ilocos Sur, Philippines (1985) Okinawa, Japan (1985)

Okinawa, Japan (1985) Pangasinan, Philippines (2002)

Pangasinan, Philippines (2002) Taiwan, ROC (1993)

Taiwan, ROC (1993) Tianjin, China (2002)

Tianjin, China (2002)

Famous people from Hawaiʻi

The list of famous people from Hawaiʻi is a comprehensive, alphabetized list of persons who have achieved fame that presently or at one time claimed Hawaiʻi as their home. Separate registers of members of the Hawaiian royal family and Hawaiʻi politicians are also available.

- Fatherdamien.jpg

Father Damien

Beatified towards sainthood by Pope John Paul II - Mother Marianne Cope.jpg

Mother Marianne Cope

Beatified towards sainthood by Pope Benedict XVI - Fong.jpg

Hiram Fong

First Chinese American and Asian American elected United States Senator - Georgeariyoshi.jpg

George R. Ariyoshi

First Japanese American and Asian American elected governor in the United States - Eric Shinseki official portrait.jpg

Eric Shinseki

First Japanese American and Asian American member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff - DukeKahanamoku.jpeg

Duke Kahanamoku

Gold-medal winning Olympic athlete (swimming) who popularized surfing

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Schamel, Wynell and Charles E. Schamel. "The 1897 Petition Against the Annexation of Hawaiʻi." Social Education 63, 7 (November/December 1999): 402-408.

See also

- Lightmatter haleakala Maui Hawaii.jpg

Haleakalā

- Kalalau Trail 2004-08-22.JPG

Na Pali Coast

External links

- Travel guide to Hawaii from Wikitravel

- Official state homepage

- Satellite image of Hawaiian Islands at NASA's Earth Observatory

- Google maps

- Bureau of Labor Statistics - Economic Data, including Hawaiʻi

- Economic History of Hawaiʻi

- Plants of Hawaiʻi

- Hawaiian Center for Volcanology (How Hawaiʻi was formed)

- Hawaii State Facts

Template:Hawaii history

Template:Pacific Islands

Template:Polynesia

| State of Hawaii Honolulu (capital) | |

| Topics | Culture |

Geography | Government | History | Music | Politics | People |

| Main Islands | Hawaii |

Kahoolawe | Kauai | Lanai | Maui | Molokai | Niihau | Oahu |

| French Frigate Shoals |

Gardner | Kure | Laysan | Lisianski | Maro Reef | Necker | Nihoa | Pearl and Hermes | |

| Communities | Hilo |

Honolulu | Kahului | Kaneohe | Waipahu | Lihue | Pearl City |

| Counties | Hawaii |

Honolulu | Kalawao | Kauai | Maui |

| Political divisions of the United States | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

ang:Hawaii ar:هاواي ast:Hawaii zh-min-nan:Hawaiʻi bg:Хаваи ca:Hawaii cs:Havaj cy:Hawaii da:Hawaii de:Hawaii et:Hawaii osariik es:Hawai eo:Havajo eu:Hawai fa:هاوائی fr:Hawaii ga:Haváí gd:Hawaii gl:Hawai - Hawai'i ko:하와이 주 haw:Hawai‘i hr:Havaji io:Havayi ilo:Hawai'i id:Hawaii os:Гавайтæ is:Hawaii it:Hawaii he:הוואי ka:ჰავაი (შტატი) kw:Hawaii la:Havaii lv:Havajas lt:Havajai hu:Hawaii mk:Хаваи mi:Hawai'i nl:Hawaï ja:ハワイ州 no:Hawaii nn:Hawaii oc:Hawaii ug:ھاۋاي شىتاتى pl:Hawaje (stan w USA) pt:Havaí ro:Hawaii (stat SUA) ru:Гавайи sq:Hawaii simple:Hawaii sk:Havaj (štát USA) sl:Havaji sr:Хаваји fi:Havaiji sv:Hawaii tl:Hawaii th:มลรัฐฮาวาย vi:Hawaii to:Hauaiʻi tr:Hawaii uk:Гаваї zh:夏威夷州