April Fools' Day

Working on —Jennifer Tanabe (talk) 17:11, 12 March 2020 (UTC)

April Fools' Day or April Fool's Day (sometimes called All Fools' Day) is an annual custom on April 1, consisting of practical jokes and hoaxes. The player of the joke or hoax often exposes their action later by shouting "April fools" at the recipient. The recipients of these actions are called April fools. Mass media can be involved in these pranks, which may be revealed as such the following day. Although popular since the 19th century, the day is not a public holiday in any country.

Origins

A disputed association between April 1 and foolishness is in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (1392).[1] In the "Nun's Priest's Tale", a vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox on Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two.[2] Readers apparently understood this line to mean "32 March", i.e. April 1.[citation needed][3] However, it is not clear that Chaucer was referencing April 1, since the text of the "Nun's Priest's Tale" also states that the story takes place on the day when the sun is in the signe of Taurus had y-runne Twenty degrees and one, which cannot be April 1. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, Syn March was gon.[4] If so, the passage would have originally meant 32 days after March, i.e. 2 May,[5] the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381.

In 1508, French poet Eloy d'Amerval referred to a poisson d'avril (April fool, literally "fish of April"), possibly the first reference to the celebration in France.[6] Some writers suggest that April Fools' originated because in the Middle Ages, New Year's Day was celebrated on March 25 in most European towns,[7] with a holiday that in some areas of France, specifically, ended on April 1,[8][9] and those who celebrated New Year's Eve on January 1 made fun of those who celebrated on other dates by the invention of April Fools' Day.[8] The use of January 1 as New Year's Day became common in France only in the mid-16th century,[5] and the date was not adopted officially until 1564, by the Edict of Roussillon.

In 1561, Flemish poet Eduard de Dene wrote of a nobleman who sent his servants on foolish errands on April 1.[5]

In the Netherlands, the origin of April Fools' Day is often attributed to the Dutch victory in 1572 at Brielle, where the Spanish Duke Álvarez de Toledo was defeated.Op 1 april verloor Alva zijn bril is a Dutch proverb, which can be translated as: "On the first of April, Alva lost his glasses." In this case, "bril" ("glasses" in Dutch) serves as a homonym for Brielle. This theory, however, provides no explanation for the international celebration of April Fools' Day.

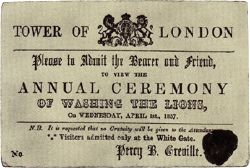

In 1686, John Aubrey referred to the celebration as "Fooles holy day", the first British reference.[5] On April 1, 1698, several people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to "see the Lions washed".[5]

Although no Biblical scholar or historian is known to have mentioned a relationship, some have expressed the belief that the origins of April Fool's Day may go back to the Genesis flood narrative. In a 1908 edition of the Harper's Weekly cartoonist Bertha R. McDonald wrote:

Authorities gravely back with it to the time of Noah and the ark. The London Public Advertiser of March 13, 1769, printed: "The mistake of Noah sending the dove out of the ark before the water had abated, on the first day of April, and to perpetuate the memory of this deliverance it was thought proper, whoever forgot so remarkable a circumstance, to punish them by sending them upon some sleeveless errand similar to that ineffectual message upon which the bird was sent by the patriarch".[10]

Long-standing customs

United Kingdom and Ireland

In the UK, an April Fool prank is sometimes later revealed by shouting "April fool!" at the recipient. These pranks are only carried out in the morning, ending at noon.[11] This continues to be the current practice, with the custom ceasing at noon, after which time it is no longer acceptable to play pranks.[12] Thus a person playing a prank after midday is considered the "April fool" themselves.[13]

Traditional tricks include pinning notes which would say things like "kick me" or "kiss me" on someone's back, and sending an unsuspecting child on some unlikely errand, such as "fetching a whistle to bring down the wind." In Scotland, the day is often called "Taily Day," which is derived from the name for a pig's tail which could be pinned on an unsuspecting victim's back.[14]

April Fools' Day was traditionally called "Huntigowk Day" in Scotland.[11] The name is a corruption of 'Hunt the Gowk', "gowk" being Scots for a cuckoo or a foolish person; alternative terms in Gaelic would be Là na Gocaireachd, 'gowking day', or Là Ruith na Cuthaige, 'the day of running the cuckoo'. The traditional prank is to ask someone to deliver a sealed message that supposedly requests help of some sort. In fact, the message reads "Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile." The recipient, upon reading it, will explain he can only help if he first contacts another person, and sends the victim to this next person with an identical message, with the same result.[11]

April Fish

In Italy, France, Belgium and French-speaking areas of Switzerland and Canada, April 1 tradition is often known as "April fish" (poisson d'avril in French, april vis in Dutch or pesce d'aprile in Italian). This includes attempting to attach a paper fish to the victim's back without being noticed.[15] Such fish feature is prominently present on many late 19th- to early 20th-century French April Fools' Day postcards.

Prima aprilis in Poland

In Poland, prima aprilis ("1 April" in Latin) as a day of pranks is a centuries-long tradition. It is a day when many pranks are played: hoaxes – sometimes very sophisticated – are prepared by people, media (which often cooperate to make the "information" more credible) and even public institutions. Serious activities are usually avoided, and generally every word said on April 1 can be untrue. The conviction for this is so strong that the Polish anti-Turkish alliance with Leopold I signed on April 1, 1683, was backdated to March 31.[16] However, for some in Poland prima aprilis ends at noon of April 1, and prima aprilis jokes after that hour are considered inappropriate and not classy.

First of April in Ukraine

April Fools' Day is widely celebrated in Odessa and has special local name Humorina. For the first time this holiday arose in 1973.[17] April Fool prank is revealed by saying "Первое Апреля, никому не верю" (which means "April First, trust nobody") at the recipient. The festival includes a large parade in the city center, free concerts, street fairs and performances. Festival participants dress up in a variety of costumes and walk around the city fooling around and pranks with passersby. One of the traditions on fool's day is to dress up the main city monument in funny clothes. Humorina even has its own logo - a cheerful sailor in life ring, whose author was an artist – Arkady Tsykun.[18] During the festival, special souvenirs with a logo are printed and sold everywhere. Since 2010, April Fools' Day celebrations include an International Clown Festival and both celebrated as one. In 2019, the festival was dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Odessa Film Studio and all events were held with an emphasis on cinema.[19]

Pranks

As well as people playing pranks on one another on April Fools' Day, elaborate pranks have appeared on radio and TV stations, newspapers, and websites, and have been performed by large corporations.

Television stations

- Spaghetti trees: The BBC television programme Panorama ran a hoax in 1957, purporting to show the Swiss harvesting spaghetti from trees. In one famous prank in 1957, the BBC broadcast a film in their Panorama current affairs series purporting to show Swiss farmers picking freshly-grown spaghetti, in what they called the Swiss Spaghetti Harvest. The BBC were later flooded with requests to purchase a spaghetti plant, forcing them to declare the film a hoax on the news the next day.[20]They claimed that the despised pest, the spaghetti weevil, had been eradicated. A large number of people contacted the BBC wanting to know how to cultivate their own spaghetti trees. It was, in fact, filmed in St Albans.[21] The editor of Panorama at the time, Michael Peacock, approved the idea, which was pitched by freelance camera operator Charles de Jaeger. Peacock told the BBC in 2014 that he gave de Jaeger a budget of £100. Peacock said the respected Panorama anchorman Richard Dimbleby knew they were using his authoritativeness to make the joke work. He said Dimbleby loved the idea and went at it with relish.[22] Decades later CNN called this broadcast "the biggest hoax that any reputable news establishment ever pulled".[23]

- In 1962, Swedish national television broadcast a 5-minute special[24] on how one could get color TV by placing a nylon stocking in front of the TV. A rather in-depth description on the physics behind the phenomenon was included. Thousands of people tried it.

- Smell-o-vision: In 1965, the BBC purported to conduct a trial of a new technology allowing the transmission of odour over the airwaves to all viewers. Many viewers reportedly contacted the BBC to report the trial's success.[25] In 2007, the BBC website repeated an online version of the hoax,[26] as did Google in 2013, in tribute.

- In 1969, the public broadcaster NTS in the Netherlands announced that inspectors with remote scanners would drive the streets to detect people who had not paid their radio/TV tax ("kijk en luistergeld" or "omroepbijdrage"). The only way to prevent detection was to wrap the TV/radio in aluminium foil. The next day all supermarkets were sold out of their aluminium foil, and a surge of TV/radio taxes were being paid.[27]

- Great Blue Hill eruption prank: On April 1, 1980, Boston television station WNAC-TV aired a fake news bulletin at the end of the 6 o'clock news which reported that Great Blue Hill in Milton, Massachusetts was erupting. The prank resulted in panic in Milton, where some residents began to flee their homes. The executive producer of the 6 o'clock news, Homer Cilley, was fired by the station for "his failure to exercise good news judgment" and for violating the Federal Communications Commission's rules about showing stock footage without identifying it as such.[28][29][30]

- In 1989, on the BBC television sports show Grandstand, a fight broke out between members of staff directly behind Des Lynam who was commenting on the professionalism of his team. At the end of the show it was revealed to be an April Fools joke.

- In 2008, the BBC reported on a newly discovered colony of flying penguins. An elaborate video segment was even produced, featuring Terry Jones walking with the penguins in Antarctica, and following their flight to the Amazon rainforest.[31]

- Netflix April Fools' Day jokes include over-detailing categories of films,[32][33] and adding original programming made up entirely of food cooking.[34][35]

Radio stations

- Jovian–Plutonian gravitational effect: In 1976, British astronomer Sir Patrick Moore told listeners of BBC Radio 2 that unique alignment of two planets would result in an upward gravitational pull making people lighter at precisely 9:47 am that day. He invited his audience to jump in the air and experience "a strange floating sensation". Dozens of listeners phoned in to say the experiment had worked,[36] among them a woman who reported that she and her 11 friends were "wafted from their chairs and orbited gently around the room."[37]

- Death of a mayor: In 1998, local WAAF shock jocks Opie and Anthony were discussing April Fool's Day hoaxes, and sardonically stated that Boston mayor Thomas Menino had been killed in a car accident. Menino happened to be on a flight at the time, lending credence to the prank as he could not be reached. The pair repeated that the mayor was dead several times throughout the broadcast, however listeners who tuned in late to the broadcast did not hear that they were repeating a bit, and when they pretended to tell the "news" to an unsuspecting listener (the listener thought she was calling a different show), the rumor spread quickly across the city, eventually causing news stations to issue alerts denying the hoax. The pair were fired shortly thereafter.[38]

- In 1998, UK presenter Nic Tuff of West Midlands radio station pretended to be the British Prime Minister Tony Blair when he called the then South African President Nelson Mandela for a chat. It was only at the end of the call when Nic asked Mandela what he was doing for April Fools' Day that the line went dead.[39]

- Archers theme tune change: BBC Radio 4 (2005): The Today Programme announced in the news that the long-running serial The Archers had changed its theme tune to an upbeat disco style.[40]

- National Public Radio in the United States: the respective producers of Morning Edition or All Things Considered annually include a fictional news story.[41] These usually start off more or less reasonably, and get more and more unusual. A recent example is the 2006 story on the "iBod," a portable body control device.[42] In 2008 it reported that the IRS, to assure rebate checks were actually spent, was shipping consumer products instead of checks.[43] It also runs false sponsor mentions, such as "Support for NPR comes from the Soylent Corporation, manufacturing protein-rich food products in a variety of colors. Soylent Green is People".[44]

- Canadian three-dollar coin: In 2008, the CBC Radio program As It Happens interviewed a Royal Canadian Mint spokesman who broke "news" of plans to replace the Canadian five-dollar bill with a three-dollar coin. The coin was dubbed a "threenie", in line with the nicknames of the country's one-dollar coin ("loonie" due to its depiction of a common loon on the reverse) and two-dollar coin ("toonie").[45]

- In 1993, a radio station in San Diego, California told listeners that the Space Shuttle had been diverted to a small, local airport. Over 1,000 people drove to the airport to see it arrive in the middle of morning rush hour. There was no shuttle flying that day.[46]

Newspapers and magazines

- Scientific American columnist Martin Gardner wrote in an April 1975, article that MIT had invented a new chess computer program that predicted "pawn to queens rook four" is always the best opening move.[47]

- In The Guardian newspaper, in the United Kingdom, on April Fools' Day, 1977, a fictional mid-ocean state of San Serriffe was created in a seven-page supplement.[48]

- A 1985 issue of Sports Illustrated, dated April 1, featured a story by George Plimpton on a baseball player, Hayden Siddhartha Finch, a New York Mets pitching prospect who could throw the ball 168 miles per hour (270 km/h) and who had a number of eccentric quirks, such as playing with one barefoot and one hiking boot. Plimpton later expanded the piece into a full-length novel on Finch's life. Sports Illustrated cites the story as one of the more memorable in the magazine's history.[49]

- Associated Press were fooled in 1983 when Joseph Boskin, a professor of history at Boston University, provided an alternative explanation for the origins of April Fools' Day. He claimed to have traced the practice to Constantine's period, when a group of court jesters jocularly told the emperor that jesters could do a better job of running the empire, and the amused emperor nominated a jester, Kugel, to be the king for a day. Boskin related how the jester passed an edict calling for absurdity on that day and the custom became an annual event. Boskin explained the jester's role as being able to put serious matters into perspective with humor. An Associated Press article brought this alternative explanation to public's attention in newspapers, not knowing that Boskin had invented the entire story as an April Fool's joke itself, and were not made aware of this until some weeks later.[50]

- Taco Liberty Bell: In 1996, Taco Bell took out a full-page advertisement in The New York Times announcing that they had purchased the Liberty Bell to "reduce the country's debt" and renamed it the "Taco Liberty Bell". When asked about the sale, White House press secretary Mike McCurry replied tongue-in-cheek that the Lincoln Memorial had also been sold and would henceforth be known as the Lincoln-Mercury Memorial.[51]

- In 2008, Car and Driver and Automobile Magazine both reported that Toyota had acquired the rights to the defunct Oldsmobile brand from General Motors and intended to relaunch it with a line-up of rebadged Toyota SUVs positioned between its mainline Toyota and luxury Lexus brands.[52][53]

Internet

- Kremvax: In 1984, in one of the earliest online hoaxes, a message was circulated that Usenet had been opened to users in the Soviet Union.[54]

- April Fools' Day Request for Comments: Almost every year since 1989, the Internet Engineering Task Force has included an April Fool in their Request for Comments publication, including a "Hyper Text Coffee Pot Control Protocol" and "Electricity over IP."

- College Mascots: For decades, printed college newspapers have run stories about their respective institutions changing to a ridiculous or silly new athletics mascot. In the internet age, the practice has moved to online editions and then to the social media pages of fanbases and alumni associations.[55]

- Dead fairy hoax: In 2007, an illusion designer for magicians posted on his website some images illustrating the corpse of an unknown eight-inch creation, which was claimed to be the mummified remains of a fairy. He later sold the fairy on eBay for £280.[56]

- Google (including YouTube, Gmail, etc.): Google is well known for the annual April Fools' jokes, beginning in 2000 and 2002, and every year since 2004.

- Bing: In 2015, Bing launched a pretend new product called the "Cute Cloud", which acted as a hub for cute animal videos and gifs.[57]

Other

- Write-only memory: Signetics advertised write-only memory (WOM) ICs in their databooks in 1972 through the late 1970s.[58]

- Decimal time: Repeated several times in various countries, this hoax involves claiming that the time system will be changed to one in which units of time are based on powers of 10.[59]

- In 2014, King's College, Cambridge released a YouTube video detailing their decision to discontinue the use of trebles ('boy sopranos') and instead use grown men who have inhaled helium gas.[60]

Reception

The practice of April Fool pranks and hoaxes is controversial.[13][61] The mixed opinions of critics are epitomized in the reception to the 1957 BBC "Spaghetti-tree hoax", in reference to which, newspapers were split over whether it was "a great joke or a terrible hoax on the public".[62]

The positive view is that April Fools' can be good for one's health because it encourages "jokes, hoaxes...pranks, [and] belly laughs", and brings all the benefits of laughter including stress relief and reducing strain on the heart.[63] There are many "best of" April Fools' Day lists that are compiled in order to showcase the best examples of how the day is celebrated.[64] Various April Fools' campaigns have been praised for their innovation, creativity, writing, and general effort.[65]

The negative view describes April Fools' hoaxes as "creepy and manipulative", "rude" and "a little bit nasty", as well as based on schadenfreude and deceit.[61] When genuine news or a genuine important order or warning is issued on April Fools' Day, there is risk that it will be misinterpreted as a joke and ignored – for example, when Google, known to play elaborate April Fools' Day hoaxes, announced the launch of Gmail with 1-gigabyte inboxes in 2004, an era when competing webmail services offered 4-megabytes or less, many dismissed it as a joke outright.[66][67] On the other hand, sometimes stories intended as jokes are taken seriously. Either way, there can be adverse effects, such as confusion,[68] misinformation, waste of resources (especially when the hoax concerns people in danger) and even legal or commercial consequences.[69][70]

People obeying hoax messages to telephone "Mr C. Lion" or "Mr L. E. Fant" and suchlike on a telephone number that turns out to be a zoo, sometimes cause a serious overload to zoos' telephone switchboards.

Other examples of genuine news on April 1 mistaken as a hoax include:

- 1 April 1946: Warnings about the Aleutian Island earthquake's tsunami that killed 165 people in Hawaii and Alaska.

- 1 April 2005: News that the comedian Mitch Hedberg had died on 29 March 2005.

- 1 April 2005: Announcement about Powerpuff Girls Z, by Aniplex, Cartoon Network and Toei Animation.[71]

- 1 April 2009: Announcement that the long running soap opera Guiding Light was being cancelled.

Notes

- ↑ Ashley Ross. "No Kidding: We Have No Idea How April Fools' Day Started", Time Magazine, March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ The Canterbury Tales, "The Nun's Priest's Tale" - "Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century", University of Maine at Machias, September 21, 2007

- ↑ Compare to Valentine's Day, a holiday that originated with a similar misunderstanding of Chaucer.

- ↑ Travis, Peter W. (1997). "Chaucer's Chronographiae, the Confounded Reader, and Fourteenth-Century Measurements of Time", Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages. Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press, 16–17. ISBN 0-8101-1541-7.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Boese, Alex (2008). The Origin of April Fool's Day.

- ↑ Eloy d'Amerval, Le Livre de la Deablerie, Librairie Droz, p. 70. (1991). "De maint homme et de mainte fame, poisson d'Apvril vien tost a moy."

- ↑ Groves, Marsha, Manners and Customs in the Middle Ages, p. 27 (2005).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 April Fools' Day. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ↑ Santino, Jack (1972). All around the year: holidays and celebrations in American life. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06516-3.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedharp - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Iona Opie and Peter Opie, The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (New York Review Books Classics, 2001, ISBN 978-0940322691).

- ↑ Office, Great Britain: Home (2017). Life in the United Kingdom: a guide for new residents, 2014 (in English), Stationery Office. ISBN 9780113413409.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Archie Bland. "The Big Question: How did the April Fool's Day tradition begin, and what are the best tricks?", The Independent, April 1, 2009. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ↑ Bridget Haggerty, April Fool's Day Irish Culture and Customs. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ↑ Margo Lestz, April Fool’s Day or April Fish Day France The Good Life France. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ↑ Origin of April Fools’ Day. The Express Tribune. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ↑ Humorina time (April 1, 2019).

- ↑ Main festival in Odessa (2019).

- ↑ Odessa celebrates Humorine. Picture story (April 1, 2019).

- ↑ Swiss Spaghetti Harvest. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Still a good joke – 47 years on (BBC News, April 1, 2004)

- ↑ BBC TV News interview with Michael Peacock 1/4/14...

- ↑ Saeed Ahmed CNN. "A nod and a link: April Fools' Day pranks abound in the news", CNN. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ↑ Instant Color TV, 1962. museumofhoaxes.com. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- ↑ April Fools' Day, 1965. Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ↑ BBC (April 1, 2007). BBC Smell-o-vision. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ↑ Geslaagde 1 aprilgrappen in Nederland (December 24, 2011). Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ↑ Loohauls, Jackie, "These practical jokers didn't fool around", March 30, 1984. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Volcano joke ends in firing", 3 April 1980. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Piot, Debra K., "TV station fires producer for airing April-fool prank", 4 April 1980. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Midgley, Neil, "Flying penguins found by BBC programme", Telegraph, April 1, 2008. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ Kleinman, Alexis, "Netflix April Fool's Day Prank: Implausibly Specific Categories", 1 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Gupta, Prachi, "Netflix's April Fools’ Day categories", 1 April 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Kolodny, Carina, "We Would Actually Watch These Delicious Netflix Prank Shows", 1 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Molina, Brett, "Netflix may have won April Fool's Day", 1 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Fooling around, book extract in The Guardian dated March 30, 2007, online at books.guardian.com (Retrieved March 29, 2009)

- ↑ "Planetary Alignment Decreases Gravity – April Fool's Day, 1976". Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Opie and Anthony: WAAF April Fools Day Prank Part 1. Youtube.com (2011-10-14). Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- ↑ Millennium TimeLine (April 1998). Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ↑ New Archers Theme Tune. Latest Reports. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ NPR's Past April Fools' Day Pranks (27 March 2016). Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ↑ Weekend Edition Saturday (April 1, 2006). www.npr.org IBOD story. Npr.org. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ↑ Gagliano, Rico (April 1, 2008). IRS making sure your rebate gets spent | Marketplace From American Public Media. Marketplace.publicradio.org. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ↑ Letters: April Fools!. Weekend Edition Sunday. NPR (April 8, 2007). Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ↑ As It Happens - 2008: Three-Dollar Coin {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ GRANBERRY, MICHAEL (April 2, 1993). April Fools' Hoax No Joke in San Diego.

- ↑ Braunlich, Tom (May 28, 2010). Martin Gardner, Mathematician and Lifelong Chess Fan, Dies at 95. The United States Chess Federation. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Top Ten April Fools' Day Jokes", Metro. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ↑ Plimpton, George (April 1, 1985). The Curious Case Of Sidd Finch 62 (13).

- ↑ Origin and History of April Fools' day. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ↑ Entry at Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Gall, Jared (March 31, 2008). Oldsmobile Returns!.

- ↑ Oldsmobile Brand Returns to Market - Latest News, Features, and Reviews (April 1, 2008).

- ↑ Raymond, E. S.: "The Jargon File", Kremvax entry, 2006

- ↑ Glenn Arthur Pierce, "I Need a Spring Break from April Fool's Day Mascots" (2016), https://www.goodreads.com/author_blog_posts/10142813-i-need-a-spring-break-from-april-fool-

- ↑ " April fool fairy sold on internet" from BBC News. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ↑ The NetElixir Blog: Digital Marketing & Retail Industry News, Tips and Insights. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ↑ The origin of the WOM – the "Write Only Memory". Archived from the original on April 28, 2007. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ↑ April Fools' Day, 1993. Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ↑ King's College Choir announces major change. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Doll, Jen (April 1, 2013). Is April Fools' Day the Worst Holiday? – Yahoo News. Yahoo! News. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Is this the best April Fool's ever?. BBC. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Why April Fools’ Day is Good For Your Health – Health News and Views. News.Health.com (April 1, 2013). Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ April Fools: the best online pranks | SBS News. Sbs.com.au. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ April Fool’s Day: A Global Practice (in en-US) (2019-04-01).

- ↑ Harry McCracken (April 1, 2013). Google's Greatest April Fools’ Hoax Ever (Hint: It Wasn’t a Hoax). TIME.com. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ↑ Lisa Baertlein. "Google: 'Gmail' no joke, but lunar jobs are", Reuters, April 1, 2004. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ↑ Woods, Michael (April 2, 2013). Brazeau tweets his resignation on April Fool's Day, causing confusion – National. Globalnews.ca. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Hasham, Nicole, "ASIC to look into prank Metgasco email from schoolgirl Kudra Falla-Ricketts", April 3, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Justin Bieber's Believe album hijacked by DJ Paz", April 3, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ Powerpuff Girls Z Debut.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Day, Brian. Chronicle of Celtic Folk Customs. Hamlyn, 2000. ISBN 978-0600598374

- Opie, Iona, and Peter Opie. The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. New York Review Books Classics, 2001. ISBN 978-0940322691

- Wainwright, Martin (2007). The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day. Aurum. Template:ISBN

- Dundes, Alan (1988). April Fool and April Fish: Towards a Theory of Ritual Pranks. Etnofoor 1 (1): 4–14.

External links

All links retrieved

- Top 100 April Fools' Day hoaxes of all time Museum of Hoaxes.

- April Fools' Day On The Web List of all known April Fools' Day Jokes websites from 2004 until present

- April Fools NPR.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.