Difference between revisions of "April Fools' Day" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (62 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | |

{{Infobox Holiday | {{Infobox Holiday | ||

|holiday_name = April Fools | |holiday_name = April Fools | ||

| − | |image = | + | |image = Aprilsnar 2001.png |

|caption = An April Fools' Day prank marking the construction of the [[Copenhagen Metro]] in 2001 | |caption = An April Fools' Day prank marking the construction of the [[Copenhagen Metro]] in 2001 | ||

|nickname = All Fools' Day | |nickname = All Fools' Day | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

|relatedto = | |relatedto = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''April Fools' Day''' or '''April Fool's Day''' (sometimes called '''All Fools' Day''') is an annual custom on April 1, consisting of [[practical joke]]s and [[hoax]]es. The player of the joke or hoax often exposes their action later by shouting " | + | '''April Fools' Day''' or '''April Fool's Day''' (sometimes called '''All Fools' Day''') is an annual custom on April 1, consisting of [[practical joke]]s and [[hoax]]es. The player of the joke or hoax often exposes their action later by shouting "April fool'" at the recipient. In more recent times, the [[mass media]] may be involved in perpetrating such pranks, which may be revealed as such the following day. Although this tradition is long-standing around much of the world, the day is not a [[public holiday]] in any country. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | Opinions are somewhat divided about whether such practices are beneficial or harmful. Laughter is good for the individual, and the coming together of the community in laughter also has a beneficial impact. However, there is a danger that the public can be misled in unfortunate and even dangerous ways by well-presented hoaxes, and the perpetrators have a responsibility to ensure public safety so that the occasion can remain joyous. | |

== Origins == | == Origins == | ||

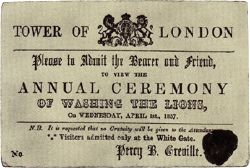

| − | [[File:Washing of the Lions.jpg|thumb|An 1857 ticket to "Washing the Lions" at the [[Tower of London]] in London. No such event ever took place.]] | + | [[File:Washing of the Lions.jpg|thumb|250px|An 1857 ticket to "Washing the Lions" at the [[Tower of London]] in London. No such event ever took place.]] |

| − | + | Despite being a well established tradition throughout northern Europe to play pranks on April 1, thus making "April Fools," there is little written record that describes its origin.<ref name=Boese>Alex Boese, [http://hoaxes.org/af_database/permalink/origin_of_april_fools_day/ The Origin of April Fool’s Day] ''The April Fool Archive''. Retrieved March 17, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | In | + | One idea is that it derives from joyful celebrations of the coming of spring. In this context, some have suggested a connection with the Greco-Roman festival called "Hilaria" which honored [[Cybele]], an ancient Greek Mother of Gods, and its celebrations included parades, masquerades, and jokes to celebrate the first day after the vernal equinox.<ref>Ashley Ross, [https://time.com/4276140/april-fools-day-history/ No Kidding: We Have No Idea How April Fools' Day Started] ''TIME'', April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> |

| − | In | + | A disputed association between April 1 and foolishness is in [[Geoffrey Chaucer]]'s ''[[The Canterbury Tales]]'' (1392). In the "[[Nun's Priest's Tale]]", a vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox on ''Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two''. Readers apparently understood this line to mean "32 March," which would be April 1. However, it is not clear that Chaucer was referencing April 1, since the text of the "Nun's Priest's Tale" also states that the story takes place on the day when the sun is ''in the signe of Taurus had y-runne Twenty degrees and one'', which cannot be April 1. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, ''Syn March was gon''.<ref>Carol Poster (ed.), ''Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages'' (Northwestern University Press, 1997). </ref> If so, the passage would have originally meant 32 days after March, or May 2.<ref name=Boese/> |

| − | + | The most popular theory about the origin of April Fool's Day involves the calendar reform of the sixteenth century, which involved changing from the [[Julian calendar]], introduced by [[Julius Caesar]], to the [[Gregorian calendar]] named for [[Pope Gregory XIII]]. This moved the New Year from March to January 1. Those still using the Julian calendar were called fools and it became customary to play jokes on them on April 1. However, there are inconsistencies with this idea. For example, in countries such as France the [[New Years Day|New Year]] celebrations had long been held on January 1. In Britain, the calendar change occurred in 1752, by which time there was clear written record of April Fools Day activities already taking place.<ref name=Boese/> | |

| − | + | The sixteenth century records evidence of the custom in various places in Europe. For example, in 1508, French poet [[Eloy d'Amerval]] referred to a ''[[poisson d'avril]]'' (April fool, literally "fish of April"), possibly the first reference to the celebration in France.<ref>Eloy d'Amerval, ''Le Livre de la Deablerie'' (Librairie Droz, 1991, ISBN 978-2600026727).</ref> | |

| − | + | In 1561, Flemish poet Eduard de Dene wrote of a nobleman who sent his servants on foolish errands on April 1. The closing line of each stanza contains the line: "I am afraid... that you are trying to make me run a fool's errand."<ref name=Boese/> | |

| − | + | By the late seventeenth century there are records of the day in Britain. In 1686, [[John Aubrey]] referred to the celebration on April 1 as "Fooles holy day," the first British reference. It became traditional for a certain prank to be played on April Fool's Day which involved inviting people were tricked to go to the [[Tower of London]] to "see the lions washed." The April 2, 1698 edition of ''Dawks's News-Letter'' reported that several people had attended the nonexistent ceremony.<ref name=Boese/> | |

== Long-standing customs == | == Long-standing customs == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === Ireland === | + | === United Kingdom and Ireland === |

| − | In | + | In the [[United Kingdom]], April Fool pranks have traditionally been carried out in the morning. and revealed by shouting "April fool!" at the recipient.<ref name=Opie>Iona Opie and Peter Opie, ''The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren'' (New York Review Books Classics, 2001, ISBN 978-0940322691).</ref> This continues to be the current practice, with the custom ceasing at noon, after which time it is no longer acceptable to play pranks. Thus a person playing a prank after midday is considered the "April fool" themselves.<ref name="Independent">Archie Bland, [https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/the-big-question-how-did-the-april-fools-day-tradition-begin-and-what-are-the-best-tricks-1658944.html The Big Question: How did the April Fool's Day tradition begin, and what are the best tricks?] ''The Independent'', April 1, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> |

| − | + | Traditional tricks include pinning notes which would say things like "kick me" or "kiss me" on someone's back, and sending an unsuspecting child on some unlikely errand, such as "fetching a whistle to bring down the wind." In [[Scotland]], the day is often called "Taily Day," which is derived from the name for a pig's tail which could be pinned on an unsuspecting victim's back.<ref>Bridget Haggerty, [http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ACalend/AprilFools.html April Fool's Day] ''Irish Culture and Customs''. Retrieved March 14, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | April Fools' Day was traditionally called "Huntigowk Day" in Scotland.<ref name=Opie/> The name is a corruption of 'Hunt the Gowk', "gowk" being [[Scots (language)|Scots]] for a cuckoo or a foolish person; alternative terms in [[Scottish Gaelic|Gaelic]] would be ''Là na Gocaireachd'', 'gowking day', or ''Là Ruith na Cuthaige'', 'the day of running the cuckoo'. The traditional prank is to ask someone to deliver a sealed message that supposedly requests help of some sort. In fact, the message reads "Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile." The recipient, upon reading it, will explain he can only help if he first contacts another person, and sends the victim to this next person with an identical message, with the same result.<ref name=Opie/> | |

| − | |||

| − | === April | + | === April Fish === |

| − | In Italy, France, Belgium and French-speaking areas of Switzerland and Canada, April | + | In [[Italy]], [[France]], [[Belgium]], and French-speaking areas of [[Switzerland]] and [[Canada]], the April Fools' tradition is often known as "April fish" (''poisson d'avril'' in French, ''april vis'' in Dutch, or ''pesce d'aprile'' in Italian). This includes attempting to attach a paper fish to the victim's back without being noticed.<ref> Margo Lestz, [https://www.thegoodlifefrance.com/april-fools-day-or-april-fish-day-france/ April Fool’s Day or April Fish Day France] ''The Good Life France''. Retrieved March 14, 2020.</ref> Such fish feature is prominently present on many late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century French April Fools' Day [[postcard]]s. |

=== First of April in Ukraine === | === First of April in Ukraine === | ||

| − | April Fools' Day is widely celebrated in Odessa and has special local name [[Humorina]]. | + | April Fools' Day is widely celebrated in [[Odessa]] and has special local name ''[[Humorina]]''. An April Fool prank is revealed by saying "''Первое Апреля, никому не верю''" (which means "April First, trust nobody") to the recipient. The history of the Humorina Odessa carnival as a city holiday begins in 1973, with the idea of a festival of laughter.<ref>[https://leodessa.com/april-fools-day/ Humorina festival in Odessa]. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The festival includes a large parade in the city center, free concerts, street fairs, and performances. Festival participants dress up in a variety of costumes, particularly clowns, and walk around the city fooling passersby.<ref>Pavlo Fedykovych, [https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/experience-odesa-during-carnival-humorina How to enjoy Odesa during the Carnival Humorina] ''Lonely Planet'', February 25, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Pranks == | == Pranks == | ||

| − | [[File:Make Way For Ducklings Prank.jpg|thumb| | + | [[File:Make Way For Ducklings Prank.jpg|thumb|right|250px|An April Fools' Day prank in [[Public Garden (Boston)|Boston's Public Garden]] warning people not to photograph sculptures.]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As well as people playing pranks on one another on April Fools' Day, elaborate pranks have appeared on radio and TV stations, newspapers, and websites, and have been performed by large corporations. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ===Television=== |

| − | + | * [[Spaghetti tree]]s: The [[BBC]] television program ''[[Panorama (TV series)|Panorama]]'' ran a hoax on April 1 1957, purporting to show [[Swiss]] people harvesting [[spaghetti]] from trees, in what they called the [[Spaghetti-tree hoax|Swiss Spaghetti Harvest]]. [[Richard Dimbleby]], the show's highly respected anchor, narrated details of the spaghetti crop over video footage of a Swiss family pulling pasta off spaghetti trees and placing it into baskets. An announcement was made that same evening that the program was a hoax. Nevertheless, the BBC was flooded with requests from viewers asking for instructions on how to grow their own spaghetti tree, to which the BBC diplomatically replied, "Place a sprig of spaghetti in a tin of tomato sauce and hope for the best." <ref>[http://www.museumofhoaxes.com/hoax/archive/permalink/the_swiss_spaghetti_harvest The Swiss Spaghetti Harvest] ''Museum of Hoaxes''. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> Half a century later it remained one of the UK's most famous April Fool's Day jokes.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/southern_counties/3591687.stm Still a good joke – 47 years on] ''BBC News'', April 1, 2004. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> | |

| + | * [[Sweden]]'s most famous April Fool's Day hoax occurred on April 1, 1962. At the time, SVT (''Sveriges Television''), the only channel in Sweden, broadcast in black and white. They broadcast a five-minute special on how one could watch color TV by placing a nylon stocking in front of the TV. A rather in-depth description on the physics behind the phenomenon was included. Thousands of people tried it.<ref>[http://hoaxes.org/archive/permalink/instant_color_tv Instant Color TV, 1962] ''Museum of Hoaxes''. Retrieved March 18, 2020. </ref> | ||

| + | * In 1969, the public broadcaster NTS in the [[Netherlands]] announced that inspectors with remote scanners would drive the streets to detect people who had not paid their radio/TV tax ("kijk en luistergeld" or "omroepbijdrage"). The only way to prevent detection was to wrap the TV/radio in [[aluminum foil]]. The next day all supermarkets were sold out of their aluminum foil, and a surge of TV/radio taxes were being paid.<ref>[https://www.allesopeenrij.nl/cultuur-2/hollanders/geslaagde-1-aprilgrappen-in-nederland/ Geslaagde 1 aprilgrappen in Nederland] ''Alles op een rij'', December 24, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | * In 2008, the [[BBC]] reported on a newly discovered colony of [[flying penguins]]. An elaborate video segment was produced, featuring [[Terry Jones]] walking with the penguins in [[Antarctica]], and following their flight to the [[Amazon]] rainforest.<ref>Neil Midgley, [https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1583517/Flying-penguins-found-by-BBC-programme.html Flying penguins found by BBC programme] ''The Telegraph'', April 1, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2020. </ref> | ||

| + | * [[Netflix]] April Fools' Day jokes include adding original programming made up entirely of food cooking.<ref>Carina Kolodny, [https://www.huffpost.com/entry/netflix-introduces-origin_n_5068507 We Would Actually Watch These Delicious Netflix Prank Shows] ''The Huffington Post'', December 6, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2020. </ref> | ||

| − | In | + | ===Radio=== |

| + | * [[Jovian–Plutonian gravitational effect]]: In 1976, British astronomer [[Sir Patrick Moore]] told listeners of [[BBC Radio 2]] that unique alignment of the planets [[Pluto]] and [[Jupiter]] would result in an upward gravitational pull making people lighter at precisely 9:47 am that day. He invited his audience to jump in the air and experience "a strange floating sensation." Dozens of listeners phoned in to say the experiment had worked, among them some who claimed to have floated around the room.<ref>[http://hoaxes.org/af_database/permalink/planetary_alignment_decreases_gravity/ Planetary Alignment Decreases Gravity (April Fool's Day - 1976)] ''Museum of Hoaxes''. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | * In 1993, a radio station in [[San Diego]], California told listeners that the [[Space Shuttle]] had been diverted to a small, local airport. Over 1,000 people drove to the airport to see it arrive in the middle of morning rush hour. There was no shuttle flying that day.<ref> Michael Granberry, [https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-04-02-mn-18176-story.html April Fools' Hoax No Joke in San Diego] ''Los Angeles Times'', April 2, 1993. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | * [[National Public Radio]] in the United States: the respective producers of [[Morning Edition]] or [[All Things Considered]] annually include a fictional news story. These usually start off more or less reasonably, and get more and more unusual. An example is the 2006 story on the "iBod," a portable body control device.<ref>[https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5317505 A Perilous Encounter with the I-Bod] ''NPR'', April 1, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Newspapers and magazines=== | |

| − | In | + | * ''[[Scientific American]]'' columnist [[Martin Gardner]] wrote in an April 1975 article that [[MIT]] had invented a new [[chess]] computer program that predicted “Pawn to Queens Rook Four” is always the best opening move.<ref>Tom Braunlich, [http://www.uschess.org/content/view/10436/588/ Martin Gardner, Mathematician and Lifelong Chess Fan, Dies at 95] ''The United States Chess Federation'', May 28, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> |

| + | * In ''[[The Guardian]]'' newspaper, in the United Kingdom, on April Fools' Day, 1977, a fictional mid-ocean state of [[San Serriffe]] was created in a seven-page supplement.<ref>Elli Narewska, Susan Gentles, and Mariam Yamin, [https://www.theguardian.com/gnmeducationcentre/archive-educational-resource-april-2012 April fool - San Serriffe: teaching resource of the month from the GNM Archive, April 2012] ''The Guardian'', March 27, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | * A 1985 issue of ''[[Sports Illustrated]]'', dated April 1, featured a story by [[George Plimpton]] on a baseball player, [[Sidd Finch|Hayden Siddhartha Finch]], a [[New York Mets]] [[pitcher|pitching]] prospect who could throw the ball {{convert|168|mph|km/h}} and who had a number of eccentric quirks, such as playing with one barefoot and one hiking boot. Plimpton later expanded the piece into a full-length novel on Finch's life. ''Sports Illustrated'' cites the story as one of the more memorable in the magazine's history.<ref>George Plimpton, [https://www.si.com/mlb/2014/10/15/curious-case-sidd-finch The Curious Case Of Sidd Finch] ''Sports Illustrated'', April 1, 1985. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | * In 2008, ''[[Car and Driver]]'' and ''[[Automobile Magazine]]'' both reported that [[Toyota]] had acquired the rights to the defunct [[Oldsmobile]] brand from [[General Motors]] and intended to relaunch it with a line-up of [[badge engineering|rebadged]] Toyota SUVs positioned between its mainline [[Toyota]] and luxury [[Lexus]] brands.<ref>Jared Gall, [https://www.caranddriver.com/news/a15146502/oldsmobile-returns-car-news/ Oldsmobile Returns!] ''Car and Driver'', March 31, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref><ref>David Gluckman, [https://www.automobilemag.com/news/oldsmobile-brand-returns-to-market/ Oldsmobile Brand Returns to Market - Latest News, Features, and Reviews] ''Automobile'', April 1, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | In | + | ===Internet=== |

| + | * [[Kremvax]]: In 1984, in one of the earliest online hoaxes, a message was circulated that [[Usenet]] had been opened to users in the [[Soviet Union]].<ref>Eric S. Raymond, [http://catb.org/~esr/jargon/html/K/kremvax.html Kremvax] ''The Jargon File''. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | * [[Dead fairy hoax]]: In 2007, an illusion designer for magicians posted on his website some images illustrating the corpse of an unknown eight-inch creation, which was claimed to be the [[mummy|mummified]] remains of a [[fairy]]. He later sold the fairy on [[eBay]] for £280.<ref> [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/derbyshire/6545667.stm April fool fairy sold on internet] ''BBC News'', April 11, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Other=== | |

| + | * [[Decimal time]]: Repeated several times in various countries, this hoax involves claiming that the time system will be changed to one in which units of time are based on powers of 10.<ref>[http://hoaxes.org/af_database/permalink/metric_time Metric Time (April Fool's Day - 1975)] ''Museum of Hoaxes''. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | * In 2014, [[King's College, Cambridge]] released a [[YouTube]] video detailing their decision to discontinue the use of trebles ('[[boy soprano]]s') and instead use grown men who have inhaled [[helium]] gas.<ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ukDAfF0-8q8 King's College Choir announces major change] ''Youtube'', March 31, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> | ||

== Reception == | == Reception == | ||

| − | The practice of April Fool pranks and hoaxes is controversial.<ref name="Independent" / | + | The practice of April Fool pranks and hoaxes is controversial.<ref name="Independent" /> The mixed opinions of critics are epitomized in the reception to the 1957 ''BBC'' "[[Spaghetti-tree hoax]]," in reference to which, newspapers were split over whether it was "a great joke or a terrible hoax on the public."<ref>[https://www.bbc.com/news/av/magazine-26723188/is-this-the-best-april-fool-s-ever Is this the best April Fool's ever?] ''BBC'', April 1, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> |

| − | The positive view is that April Fools' can be good for one's health because it encourages "jokes, hoaxes...pranks, [and] belly laughs" | + | The positive view is that April Fools' can be good for one's health because it encourages "jokes, hoaxes...pranks, [and] belly laughs," and brings all the benefits of laughter including stress relief and reducing strain on the heart.<ref>Ashley Macha, [http://news.health.com/2013/04/01/why-april-fools-day-is-good-for-your-health/ Why April Fools’ Day is Good For Your Health] ''Health.com'', April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> There are many "best of" April Fools' Day lists that are compiled in order to showcase the best examples of how the day is celebrated.<ref> Stephanie Anderson, [https://www.sbs.com.au/news/april-fools-the-best-online-pranks April Fools: the best online pranks] ''SBS News'', April 1, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> Various April Fools' campaigns have been praised for their innovation, creativity, writing, and general effort.<ref>Lois Effiong, April Fool’s Day: A Global Practice ''Aljazira'', April 1, 2019.</ref> |

| − | The negative view describes April Fools' hoaxes as "creepy and manipulative" | + | The negative view describes April Fools' hoaxes as "creepy and manipulative," "rude," and "a little bit nasty," as well as based on ''[[schadenfreude]]'' and deceit.<ref>Jen Doll and Rebecca Greenfield, [https://news.yahoo.com/april-fools-day-worst-holiday-175852795.html Is April Fools' Day the Worst Holiday?] ''The Atlantic Wire'', April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2020.</ref> When genuine news or a genuine important order or warning is issued on April Fools' Day, there is risk that it will be misinterpreted as a joke and ignored. On the other hand, sometimes stories intended as jokes are taken seriously. Either way, there can be adverse effects, such as confusion, misinformation, waste of resources (especially when the hoax concerns people in danger), and even legal or commercial consequences. |

| − | + | == Notes == | |

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | + | == References == | |

| − | * | + | * d'Amerval, Eloy. ''Le Livre de la Deablerie''. Librairie Droz, 1991. ISBN 978-2600026727 |

| − | * | + | * Day, Brian. ''Chronicle of Celtic Folk Customs''. Hamlyn, 2000. ISBN 978-0600598374 |

| − | * | + | * Groves, Marsha. ''Manners and Customs in the Middle Ages''. Crabtree Pub. Co., 2005. ISBN 978-0778713890 |

| − | * | + | * Opie, Iona, and Peter Opie. ''The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren''. New York Review Books Classics, 2001. ISBN 978-0940322691 |

| + | * Poster, Carol (ed.). ''Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages''. Northwestern University Press, 1997. | ||

| + | * Santino, Jack. ''All Around the Year: Holidays and Celebrations in American Life''. University of Illinois Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0252065163 | ||

| + | * Wainwright, Martin. ''The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day''. Aurum Press Ltd, 2007. ISBN 978-1845131555 | ||

| − | == | + | == External links == |

| − | + | All links retrieved August 11, 2023. | |

| − | + | * [http://hoaxes.org/aprilfool/ Top 100 April Fools' Day hoaxes of all time] Museum of Hoaxes. | |

| − | + | * [http://aprilfoolsdayontheweb.com/ April Fools' Day On The Web] List of all known April Fools' Day Jokes websites from 2004 until present | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{US Holidays}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Holiday]] | [[Category:Holiday]] | ||

[[Category:Lifestyle]] | [[Category:Lifestyle]] | ||

| − | {{Credits|April_Fools'_Day|945009345}} | + | {{Credits|April_Fools'_Day|945009345|List_of_April_Fools'_Day_jokes|944770847}} |

Latest revision as of 15:56, 11 August 2023

April Fools' Day or April Fool's Day (sometimes called All Fools' Day) is an annual custom on April 1, consisting of practical jokes and hoaxes. The player of the joke or hoax often exposes their action later by shouting "April fool'" at the recipient. In more recent times, the mass media may be involved in perpetrating such pranks, which may be revealed as such the following day. Although this tradition is long-standing around much of the world, the day is not a public holiday in any country.

Opinions are somewhat divided about whether such practices are beneficial or harmful. Laughter is good for the individual, and the coming together of the community in laughter also has a beneficial impact. However, there is a danger that the public can be misled in unfortunate and even dangerous ways by well-presented hoaxes, and the perpetrators have a responsibility to ensure public safety so that the occasion can remain joyous.

Origins

Despite being a well established tradition throughout northern Europe to play pranks on April 1, thus making "April Fools," there is little written record that describes its origin.[1]

One idea is that it derives from joyful celebrations of the coming of spring. In this context, some have suggested a connection with the Greco-Roman festival called "Hilaria" which honored Cybele, an ancient Greek Mother of Gods, and its celebrations included parades, masquerades, and jokes to celebrate the first day after the vernal equinox.[2]

A disputed association between April 1 and foolishness is in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (1392). In the "Nun's Priest's Tale", a vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox on Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two. Readers apparently understood this line to mean "32 March," which would be April 1. However, it is not clear that Chaucer was referencing April 1, since the text of the "Nun's Priest's Tale" also states that the story takes place on the day when the sun is in the signe of Taurus had y-runne Twenty degrees and one, which cannot be April 1. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, Syn March was gon.[3] If so, the passage would have originally meant 32 days after March, or May 2.[1]

The most popular theory about the origin of April Fool's Day involves the calendar reform of the sixteenth century, which involved changing from the Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar, to the Gregorian calendar named for Pope Gregory XIII. This moved the New Year from March to January 1. Those still using the Julian calendar were called fools and it became customary to play jokes on them on April 1. However, there are inconsistencies with this idea. For example, in countries such as France the New Year celebrations had long been held on January 1. In Britain, the calendar change occurred in 1752, by which time there was clear written record of April Fools Day activities already taking place.[1]

The sixteenth century records evidence of the custom in various places in Europe. For example, in 1508, French poet Eloy d'Amerval referred to a poisson d'avril (April fool, literally "fish of April"), possibly the first reference to the celebration in France.[4]

In 1561, Flemish poet Eduard de Dene wrote of a nobleman who sent his servants on foolish errands on April 1. The closing line of each stanza contains the line: "I am afraid... that you are trying to make me run a fool's errand."[1]

By the late seventeenth century there are records of the day in Britain. In 1686, John Aubrey referred to the celebration on April 1 as "Fooles holy day," the first British reference. It became traditional for a certain prank to be played on April Fool's Day which involved inviting people were tricked to go to the Tower of London to "see the lions washed." The April 2, 1698 edition of Dawks's News-Letter reported that several people had attended the nonexistent ceremony.[1]

Long-standing customs

United Kingdom and Ireland

In the United Kingdom, April Fool pranks have traditionally been carried out in the morning. and revealed by shouting "April fool!" at the recipient.[5] This continues to be the current practice, with the custom ceasing at noon, after which time it is no longer acceptable to play pranks. Thus a person playing a prank after midday is considered the "April fool" themselves.[6]

Traditional tricks include pinning notes which would say things like "kick me" or "kiss me" on someone's back, and sending an unsuspecting child on some unlikely errand, such as "fetching a whistle to bring down the wind." In Scotland, the day is often called "Taily Day," which is derived from the name for a pig's tail which could be pinned on an unsuspecting victim's back.[7]

April Fools' Day was traditionally called "Huntigowk Day" in Scotland.[5] The name is a corruption of 'Hunt the Gowk', "gowk" being Scots for a cuckoo or a foolish person; alternative terms in Gaelic would be Là na Gocaireachd, 'gowking day', or Là Ruith na Cuthaige, 'the day of running the cuckoo'. The traditional prank is to ask someone to deliver a sealed message that supposedly requests help of some sort. In fact, the message reads "Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile." The recipient, upon reading it, will explain he can only help if he first contacts another person, and sends the victim to this next person with an identical message, with the same result.[5]

April Fish

In Italy, France, Belgium, and French-speaking areas of Switzerland and Canada, the April Fools' tradition is often known as "April fish" (poisson d'avril in French, april vis in Dutch, or pesce d'aprile in Italian). This includes attempting to attach a paper fish to the victim's back without being noticed.[8] Such fish feature is prominently present on many late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century French April Fools' Day postcards.

First of April in Ukraine

April Fools' Day is widely celebrated in Odessa and has special local name Humorina. An April Fool prank is revealed by saying "Первое Апреля, никому не верю" (which means "April First, trust nobody") to the recipient. The history of the Humorina Odessa carnival as a city holiday begins in 1973, with the idea of a festival of laughter.[9]

The festival includes a large parade in the city center, free concerts, street fairs, and performances. Festival participants dress up in a variety of costumes, particularly clowns, and walk around the city fooling passersby.[10]

Pranks

As well as people playing pranks on one another on April Fools' Day, elaborate pranks have appeared on radio and TV stations, newspapers, and websites, and have been performed by large corporations.

Television

- Spaghetti trees: The BBC television program Panorama ran a hoax on April 1 1957, purporting to show Swiss people harvesting spaghetti from trees, in what they called the Swiss Spaghetti Harvest. Richard Dimbleby, the show's highly respected anchor, narrated details of the spaghetti crop over video footage of a Swiss family pulling pasta off spaghetti trees and placing it into baskets. An announcement was made that same evening that the program was a hoax. Nevertheless, the BBC was flooded with requests from viewers asking for instructions on how to grow their own spaghetti tree, to which the BBC diplomatically replied, "Place a sprig of spaghetti in a tin of tomato sauce and hope for the best." [11] Half a century later it remained one of the UK's most famous April Fool's Day jokes.[12]

- Sweden's most famous April Fool's Day hoax occurred on April 1, 1962. At the time, SVT (Sveriges Television), the only channel in Sweden, broadcast in black and white. They broadcast a five-minute special on how one could watch color TV by placing a nylon stocking in front of the TV. A rather in-depth description on the physics behind the phenomenon was included. Thousands of people tried it.[13]

- In 1969, the public broadcaster NTS in the Netherlands announced that inspectors with remote scanners would drive the streets to detect people who had not paid their radio/TV tax ("kijk en luistergeld" or "omroepbijdrage"). The only way to prevent detection was to wrap the TV/radio in aluminum foil. The next day all supermarkets were sold out of their aluminum foil, and a surge of TV/radio taxes were being paid.[14]

- In 2008, the BBC reported on a newly discovered colony of flying penguins. An elaborate video segment was produced, featuring Terry Jones walking with the penguins in Antarctica, and following their flight to the Amazon rainforest.[15]

- Netflix April Fools' Day jokes include adding original programming made up entirely of food cooking.[16]

Radio

- Jovian–Plutonian gravitational effect: In 1976, British astronomer Sir Patrick Moore told listeners of BBC Radio 2 that unique alignment of the planets Pluto and Jupiter would result in an upward gravitational pull making people lighter at precisely 9:47 am that day. He invited his audience to jump in the air and experience "a strange floating sensation." Dozens of listeners phoned in to say the experiment had worked, among them some who claimed to have floated around the room.[17]

- In 1993, a radio station in San Diego, California told listeners that the Space Shuttle had been diverted to a small, local airport. Over 1,000 people drove to the airport to see it arrive in the middle of morning rush hour. There was no shuttle flying that day.[18]

- National Public Radio in the United States: the respective producers of Morning Edition or All Things Considered annually include a fictional news story. These usually start off more or less reasonably, and get more and more unusual. An example is the 2006 story on the "iBod," a portable body control device.[19]

Newspapers and magazines

- Scientific American columnist Martin Gardner wrote in an April 1975 article that MIT had invented a new chess computer program that predicted “Pawn to Queens Rook Four” is always the best opening move.[20]

- In The Guardian newspaper, in the United Kingdom, on April Fools' Day, 1977, a fictional mid-ocean state of San Serriffe was created in a seven-page supplement.[21]

- A 1985 issue of Sports Illustrated, dated April 1, featured a story by George Plimpton on a baseball player, Hayden Siddhartha Finch, a New York Mets pitching prospect who could throw the ball 168 miles per hour (270 km/h) and who had a number of eccentric quirks, such as playing with one barefoot and one hiking boot. Plimpton later expanded the piece into a full-length novel on Finch's life. Sports Illustrated cites the story as one of the more memorable in the magazine's history.[22]

- In 2008, Car and Driver and Automobile Magazine both reported that Toyota had acquired the rights to the defunct Oldsmobile brand from General Motors and intended to relaunch it with a line-up of rebadged Toyota SUVs positioned between its mainline Toyota and luxury Lexus brands.[23][24]

Internet

- Kremvax: In 1984, in one of the earliest online hoaxes, a message was circulated that Usenet had been opened to users in the Soviet Union.[25]

- Dead fairy hoax: In 2007, an illusion designer for magicians posted on his website some images illustrating the corpse of an unknown eight-inch creation, which was claimed to be the mummified remains of a fairy. He later sold the fairy on eBay for £280.[26]

Other

- Decimal time: Repeated several times in various countries, this hoax involves claiming that the time system will be changed to one in which units of time are based on powers of 10.[27]

- In 2014, King's College, Cambridge released a YouTube video detailing their decision to discontinue the use of trebles ('boy sopranos') and instead use grown men who have inhaled helium gas.[28]

Reception

The practice of April Fool pranks and hoaxes is controversial.[6] The mixed opinions of critics are epitomized in the reception to the 1957 BBC "Spaghetti-tree hoax," in reference to which, newspapers were split over whether it was "a great joke or a terrible hoax on the public."[29]

The positive view is that April Fools' can be good for one's health because it encourages "jokes, hoaxes...pranks, [and] belly laughs," and brings all the benefits of laughter including stress relief and reducing strain on the heart.[30] There are many "best of" April Fools' Day lists that are compiled in order to showcase the best examples of how the day is celebrated.[31] Various April Fools' campaigns have been praised for their innovation, creativity, writing, and general effort.[32]

The negative view describes April Fools' hoaxes as "creepy and manipulative," "rude," and "a little bit nasty," as well as based on schadenfreude and deceit.[33] When genuine news or a genuine important order or warning is issued on April Fools' Day, there is risk that it will be misinterpreted as a joke and ignored. On the other hand, sometimes stories intended as jokes are taken seriously. Either way, there can be adverse effects, such as confusion, misinformation, waste of resources (especially when the hoax concerns people in danger), and even legal or commercial consequences.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Alex Boese, The Origin of April Fool’s Day The April Fool Archive. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ↑ Ashley Ross, No Kidding: We Have No Idea How April Fools' Day Started TIME, April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Carol Poster (ed.), Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages (Northwestern University Press, 1997).

- ↑ Eloy d'Amerval, Le Livre de la Deablerie (Librairie Droz, 1991, ISBN 978-2600026727).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Iona Opie and Peter Opie, The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (New York Review Books Classics, 2001, ISBN 978-0940322691).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Archie Bland, The Big Question: How did the April Fool's Day tradition begin, and what are the best tricks? The Independent, April 1, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Bridget Haggerty, April Fool's Day Irish Culture and Customs. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ↑ Margo Lestz, April Fool’s Day or April Fish Day France The Good Life France. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ↑ Humorina festival in Odessa. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Pavlo Fedykovych, How to enjoy Odesa during the Carnival Humorina Lonely Planet, February 25, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ The Swiss Spaghetti Harvest Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Still a good joke – 47 years on BBC News, April 1, 2004. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Instant Color TV, 1962 Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Geslaagde 1 aprilgrappen in Nederland Alles op een rij, December 24, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Neil Midgley, Flying penguins found by BBC programme The Telegraph, April 1, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Carina Kolodny, We Would Actually Watch These Delicious Netflix Prank Shows The Huffington Post, December 6, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Planetary Alignment Decreases Gravity (April Fool's Day - 1976) Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Michael Granberry, April Fools' Hoax No Joke in San Diego Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1993. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ A Perilous Encounter with the I-Bod NPR, April 1, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Tom Braunlich, Martin Gardner, Mathematician and Lifelong Chess Fan, Dies at 95 The United States Chess Federation, May 28, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Elli Narewska, Susan Gentles, and Mariam Yamin, April fool - San Serriffe: teaching resource of the month from the GNM Archive, April 2012 The Guardian, March 27, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ George Plimpton, The Curious Case Of Sidd Finch Sports Illustrated, April 1, 1985. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jared Gall, Oldsmobile Returns! Car and Driver, March 31, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ David Gluckman, Oldsmobile Brand Returns to Market - Latest News, Features, and Reviews Automobile, April 1, 2008.

- ↑ Eric S. Raymond, Kremvax The Jargon File. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ April fool fairy sold on internet BBC News, April 11, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Metric Time (April Fool's Day - 1975) Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ King's College Choir announces major change Youtube, March 31, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Is this the best April Fool's ever? BBC, April 1, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Ashley Macha, Why April Fools’ Day is Good For Your Health Health.com, April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Stephanie Anderson, April Fools: the best online pranks SBS News, April 1, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Lois Effiong, April Fool’s Day: A Global Practice Aljazira, April 1, 2019.

- ↑ Jen Doll and Rebecca Greenfield, Is April Fools' Day the Worst Holiday? The Atlantic Wire, April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- d'Amerval, Eloy. Le Livre de la Deablerie. Librairie Droz, 1991. ISBN 978-2600026727

- Day, Brian. Chronicle of Celtic Folk Customs. Hamlyn, 2000. ISBN 978-0600598374

- Groves, Marsha. Manners and Customs in the Middle Ages. Crabtree Pub. Co., 2005. ISBN 978-0778713890

- Opie, Iona, and Peter Opie. The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. New York Review Books Classics, 2001. ISBN 978-0940322691

- Poster, Carol (ed.). Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages. Northwestern University Press, 1997.

- Santino, Jack. All Around the Year: Holidays and Celebrations in American Life. University of Illinois Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0252065163

- Wainwright, Martin. The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day. Aurum Press Ltd, 2007. ISBN 978-1845131555

External links

All links retrieved August 11, 2023.

- Top 100 April Fools' Day hoaxes of all time Museum of Hoaxes.

- April Fools' Day On The Web List of all known April Fools' Day Jokes websites from 2004 until present

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.