Cybele

Cybele (Greek Κυβέλη) was a Phrygian goddess originating in the mythology of ancient Anatolia, whose worship spread to the cities of ancient Greece and the Roman Empire. She represented the Mother Earth and was worshiped as a goddess of fertility, nature, caverns, and mountains, as well as walls and fortresses. Like other ancient goddesses, such as Gaia (the "Earth"), she was known as potnia theron, referring to her ancient Neolithic roots as "Mistress of the Animals."

The goddess was known among the Greeks as Meter ("Mother") or Meter oreie ("Mountain-Mother"), possibly in connection to the myth that she was born on Mount Ida in Anatolia. Her Roman equivalent was Magna Mater, or "Great Mother." Additionally, she was worshiped as a deity of rebirth in connection with her consort (and son), Attis.

Etymology

The traditional derivation of Cybele as "she of the hair" is no longer accepted because an inscription found in one of her Phrygian rock-cut monuments has been rendered, matar kubileya,[1] meaning "Mother of the Mountain."[2] The inscription matar occurs frequently in other Phrygian sites.[3]

Others scholars have proposed that Cybele's name can be traced to Kubaba, the deified queen of the Third Dynasty of Kish, worshiped at Carchemish and Hellenized to Kybebe.[4] With or without the etymological connection, Kubaba and Matar certainly merged in at least some aspects, as the genital mutilation later connected with Cybele's cult is associated with Kybebe in earlier texts; but in general she seems to have been more a collection of similar tutelary goddesses associated with specific Anatolian mountains or other localities, and called simply "mother."[5]

History

Cybele's origins are debated by scholars. Ancient texts and inscriptions clearly associate the goddess with Phrygian origins in Anatolia. It was well known that an archaic version of Cybele had been venerated at Pessinos in Phrygia, before its aniconic cult object was removed to Rome in 203 B.C.E. However, if the theory on the Kubaba origin of Cybele's name is correct (as addressed in the Etymology section above), then Kubaba must have merged with the various local mother goddesses well before the time of the Phrygian Matar Kubileya inscription made around the first half of the sixth century B.C.E.[6] Burkert notes that by the second millennium B.C.E., the Kubaba of Bronze Age Carchemish was known to the Hittites and Hurrians: "[O]n the basis of inscriptional and iconographical evidence it is possible to trace the diffusion of her cult in the early Iron Age; the cult reached the Phrygians in inner Anatolia, where it took on special significance."[7]

In Phrygia, Cybele was venerated as Agdistis, with a temple at the great trading city Pessinos, mentioned by the geographer Strabo. It was at Pessinos that her son and lover, Attis, was about to wed the daughter of the king, when Cybele appeared in her awesome glory, and he castrated himself.

The worship of Cybele spread from inland areas of Anatolia and Syria to the Aegean coast, to Crete and other Aegean islands, and to mainland Greece. Her cult moved from Phrygia to Greece between the sixth century B.C.E. to the fourth B.C.E. Cybele's cult in Greece was closely associated with, and apparently resembled, the cult of Dionysus, whom Cybele is said to have initiated, and cured him of Hera's madness. The Greeks also identified Cybele with the Mother of the Gods, Rhea. Her cult had already been adopted in fifth century B.C.E. Greece, where she is often referred to euphemistically as Meter Theon Idaia ("Mother of the Gods, from Mount Ida") rather than by name. Mentions of Cybele's worship are found in Pindar and Euripides, among others. Classical Greek writers, however, either did not know of or did not mention the transgendered galli; although they did know of the castration of Attis.

The geographer Strabo (Book X, 3:18) noted that the goddess was welcomed at Athens:

Just as in all other respects the Athenians continue to be hospitable to things foreign, so also in their worship of the gods; for they welcomed so many of the foreign rites … the Phrygian [rites of Rhea-Cybele are mentioned] by Demosthenes, when he casts the reproach upon Aeskhines' mother and Aeskhines himself, that he was with her when she conducted initiations, that he joined her in leading the Dionysiac march, and that many a time he cried out evoe saboe, and hyes attes, attes hyes; for these words are in the ritual of Sabazios and the Mother [Rhea].

In Alexandria, Cybele was worshiped by the Greek population as "The Mother of the Gods, the Savior who Hears our Prayers" and as "The Mother of the Gods, the Accessible One." Ephesus, one of the major trading centers of the area, was devoted to Cybele as early as the tenth century B.C.E., and the city's ecstatic celebration, the Ephesia, honored her.

The goddess was not welcome among the Scythians north of Thrace. From Herodotus (4.76-7) it is made clear that the Scythian Anacharsis (sixth century B.C.E.), after traveling among the Greeks and acquiring vast knowledge, was put to death by his fellow Scythians for attempting to introduce the foreign cult of Magna Mater.

Atalanta and Hippomenes were turned into lions by Zeus or Cybele as punishment for having sex in one of her temples, because the Greeks believed that lions could not mate with other lions. Another account says that Aphrodite turned them into lions for forgetting to do her tribute. As lions they then drew Cybele's chariot.

Walter Burkert, who treats Meter among "foreign gods" in Greek Religion (1985, section III.3,4) puts it succinctly: "The cult of the Great Mother, Meter, presents a complex picture insofar as indigenous, Minoan-Mycenean tradition is here intertwined with a cult taken over directly from the Phrygian kingdom of Asia Minor" (p 177).

In 203 or 205 B.C.E., Pessinos's aniconic cult object that embodied the Great Mother was ceremoniously and reverently removed to Rome, marking the official beginning of her cult there. Thus, by 203 B.C.E., Rome had adopted her cult as well. Rome was then embroiled in the Second Punic War. The previous year, an inspection had been made of the Sibylline Books, and some oracular verses had been discovered that announced that if a foreign foe should carry war into Italy, he could be driven out and conquered if the Mater Magna were brought from Pessinos to Rome. Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica was ordered to go to the port of Ostia, accompanied by all the matrons, to meet the goddess. He was to receive her as she left the vessel, and when brought to land he was to place her in the hands of the matrons who were to bear her to her destination, the Temple of Victory on the Palatine Hill. The day on which this event took place, April 12, was observed afterwards as a festival, the Megalesian.[8]

In 103 B.C.E., Battakes, a high priest of Cybele, journeyed to Rome to announce a prediction of Gaius Marius's victory over the Cimbri and Teutoni. A. Pompeius, plebeian tribune, together with a band of ruffians, chased Battakes off of the Rostra. Pompeius supposedly died of a fever a few days later.[9]

Under the emperor Augustus, Cybele enjoyed greater prominence thanks to her inclusion in Augustan ideology. Augustus restored Cybele's temple, which was located next to his own palace on the Palatine Hill. On the cuirass of the Prima Porta of Augustus, the tympanon of Cybele lies at the feet of the goddess Tellus. Livia, the wife of Augustus, ordered cameo-cutters to portray her as Cybele.[10] The Malibu statue of Cybele bears the visage of Livia.[11]

In Roman mythology, she was given the name Magna Mater deorum Idaea ("great Idaean mother of the gods"), in recognition of her Phrygian origins (though this title was also given to Rhea).

Roman devotion to Cybele ran deep. Not coincidentally, when a Christian basilica was built over the site of a temple to Cybele to occupy the site, it was syncretistically dedicated as the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. However, Roman citizens were later forbidden to become priestesses of Cybele, who were eunuchs like their Asiatic Goddess.

The worship of Cybele was exported to the empire, even as far as Mauretania, where, just outside Setif, the ceremonial "tree-bearers" and the faithful (religiosi) restored the temple of Cybele and Attis after a disastrous fire in 288 C.E. Lavish new fittings paid for by the private group included the silver statue of Cybele and the chariot that carried her in procession received a new canopy, with tassels in the form of fir cones.[12] The popularity of the Cybele cult in the city of Rome and throughout the empire is thought to have inspired the author of Book of Revelation to allude to her in his portrayal of the mother of harlots who rides the Beast.

Today, a modern monumental statue of Cybele can be found in one of the principal traffic circles of Madrid, the Plaza de Cibeles.

Ritual worship

Cybele was associated with the mystery religion concerning her son, Attis, who was castrated and resurrected. Her most ecstatic followers were males who ritually castrated themselves, and then assumed "female" identities by wearing women's clothing. These eunuchs were referred to by the third-century commentator Callimachus in the feminine Gallai, and who other contemporary commentators in ancient Greece and Rome referred to as Gallos or Galli.

These castrated "priestesses" led the people in orgiastic ceremonies with wild music, drumming, dancing and drink. The Phrygian kurbantes or Corybantes, expressed her ecstatic and orgiastic cult in music, especially drumming, clashing of shields and spears, dancing, singing and shouts, all at night. Additionally, the dactyls (Greek for "fingers") were small phallic male beings associated with the Great Mother, Cybele, and part of her retinue.

Iconography

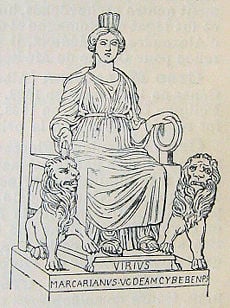

Various aspects of Cybele's Anatolian attributes probably predate the Bronze Age in origin. A figurine found at Çatalhöyük, (Archaeological Museum, Ankara), dating about 6000 B.C.E., depicts a corpulent and fertile Mother Goddess in the process of giving birth while seated on her throne, which has two hand rests in the form of lion's heads. No direct connection with the later matar goddesses is documented, but the similarity to some of the later iconography is striking.

In archaic Phrygian images of Cybele of the sixth century, already betraying the influence of Greek style, her typical representation is in the figuration of a building’s facade, standing in the doorway. The facade itself can be related to the rock-cut monuments of the highlands of Phrygia. She is wearing a belted long dress, a polos (high cylindrical hat), and a veil covering the whole body. In Phrygia, her usual attributes are the bird of prey and a small vase. Lions are sometimes related to her, in an aggressive but tamed manner.

Later, under Hellenic influence along the coast lands of Asia Minor, the sculptor Agoracritos, a pupil of Pheidias, produced a version of Cybele that became the standard one. It showed her still seated on a throne but now more decorous and matronly, her hand resting on the neck of a perfectly still lion and the other holding the circular frame drum, similar to a tambourine, (tymbalon or tympanon), which evokes the full moon in its shape and is covered with the hide of the sacred lunar bull.

From the eighth–sixth centuries B.C.E., the goddess appears alone. However, later she is joined by her son and consort Attis, who incurred her jealousy. He, in an ecstasy, castrated himself, and subsequently died. Grieving, Cybele resurrected him. This tale is told by Catullus in one of his carmina (short poems). The evergreen pine and ivy were sacred to Attis.

Some ecstatic followers of Cybele, known in Rome as galli, willingly castrated themselves in imitation of Attis. For Roman devotees of Cybele Mater Magna who were not prepared to go so far, the testicles of a bull, one of the Great Mother's sacred animals, were an acceptable substitute, as many inscriptions show. An inscription of 160 C.E. records that a certain Carpus had transported bull's testes from Rome to Cybele's shrine at Lyon, France.

Cybele in the Aeneid

In his Aeneid, Virgil called her Berecyntian Cybele, alluding to her place of birth. She is described as the mother of the gods.

In the story, the Trojans are in Italy and have kept themselves safe in a walled city according to Aeneas's orders. The leader of the Rutulians, Turnus, orders his men to burn the ships of the Trojans.

At this point in the story, there is a flashback to mount Olympus years before the Trojan War. After Cybele had given her sacred trees to the Trojans so that they could build their ships, she went to Zeus and begged him to make the ships indestructible. Zeus granted her request by saying that when the ships had finally fulfilled their purpose (bringing Aeneas and his army to Italy) they would be turned into sea nymphs rather than be destroyed.

So, as Turnus approached with fire, the ships came to life, dove beneath the sea and emerged as nymphs.

Notes

- ↑ C.H.E. Haspels, The Highlands of Phrygia (1971).

- ↑ Roller 1999, p. 67–68.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Munn 2004, Motz 1997, p. 105-106.

- ↑ Lotte Motz, The Faces of the Goddess (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- ↑ Vassileva 2001.

- ↑ Burkert, III.3.4, p. 177.

- ↑ Livy, History of Rome, 29.10-1,1 .14 (c. 10 C.E.).

- ↑ Plutarch, "Life of Marius," 17.

- ↑ P. Lambrechts, "Livie-Cybele," La Nouvelle Clio 4 (1952): 251-60.

- ↑ C. C. Vermeule, "Greek and Roman Portraits in North American Collections Open to the Public," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 108 (1964): 106, 126, fig. 18.

- ↑ Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians, p 581.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982.

- Lane, Eugene, ed. Cybele, Attis, and Related Cults: Essays in Memory of M.J. Vermaseren. E.J. Brill, 1996.

- Motz, Lotte. The Faces of the Goddess. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195089677

- Roller, Lynn Emrich. In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0520210247

- Vassileva, Maya. "Further considerations on the cult of Cybele." Anatolian Studies 5(1) (2001): 51-63.

- Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef. Cybele and Attis: The Myth and the Cult. Trans. by A. M. H. Lemmers. Thames and Hudson, 1977.

- Virgil. The Aeneid. Trans by West, David. Penguin Putnam Inc., 2003. ISBN 0140449329

External links

All links retrieved January 12, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.