Difference between revisions of "African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

Other events of the summer of 1963 were as follows: | Other events of the summer of 1963 were as follows: | ||

| − | On June 11, 1963, [[George Wallace]], Governor of Alabama, | + | On June 11, 1963, [[George Wallace]], Governor of Alabama, attempted to block the integration of the [[University of Alabama]]. President [[John F. Kennedy]] dispatched enough force to make Governor Wallace step aside, thereby allowing the enrollment of two black students. That evening, JFK addressed the nation via TV and radio with an historic civil rights speech.<ref>"Radio and Television Report to the American People on Civil Rights," June 11 1963, [http://www.jfklibrary.org/j061163.htm transcript from the JFK library.]</ref> The next day, in Mississippi, Medgar Evers was assassinated.<ref>[http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/english/ms-writers/dir/evers_medgar/ Medgar Evers,] a worthwhile article, on The Mississippi Writers Page, a website of the University of Mississippi English Department.</ref> The following week, as promised, on June 19, 1963, JFK submitted his Civil Rights bill to Congress.<ref name="abbeville">[http://www.abbeville.com/civilrights/washington.asp Civil Rights bill submitted, and date of JFK murder, plus graphic events of the March on Washington.] This is an Abbeville Press website, a large informative article apparently from their book ''The Civil Rights Movement'' (ISBN 0-7892-0123-2).</ref> |

===The March on Washington (1963)=== | ===The March on Washington (1963)=== | ||

| Line 164: | Line 164: | ||

{{main|Freedom Summer}} | {{main|Freedom Summer}} | ||

| − | + | In Mississippi, during the summer of 1964 ("[[Freedom Summer]]"), the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) used its resources to recruit more than one hundred college students, many from outside the state, to join with local activists in registering voters; teaching at "Freedom Schools"; and organizing the [[Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party]]. The work was still as dangerous as ever, and on June 21, three civil rights workers ([[James Chaney]], a young black Mississippian and plasterer's apprentice; [[Andrew Goodman]], a white anthropology student from [[Queens College, New York|Queens College]]; and [[Michael Schwerner]], a white social worker from [[Manhattan]]'s [[Lower East Side]]) were all abducted and murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan, among whom were deputies of the [[Neshoba County]] sheriff's department. | |

| − | The national uproar | + | The disappearance of the three men sparked a national uproar. What followed was a [[Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)]] inquiry, although President [[Lyndon B. Johnson|Johnson]] had to use indirect threats of political reprisals against [[J. Edgar Hoover]], to force the indifferent Bureau Director to actually conduct the investigation. After bribing at least one the murderers for details regarding the crime, the FBI found the victims' bodies on August 4, in an earthen dam on the outskirts of [[Philadelphia, Mississippi]]. Schwerner and Goodman had been shot once. Chaney, the lone black, had been savagely beaten and shot three times. During the course of that investigation, the FBI also discovered the bodies of a number of other Mississippi blacks whose disappearances had been reported over the past several years without arousing any interest or concern beyond their local communities. |

| − | The disappearance of these three activists remained | + | The disappearance of these three activists remained on the public interest frontburner for the entire month and-a-half until their bodies were found. Johnson used both the outrage over their deaths and his redoubtable political skills to bring about the passage of the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]], which bars discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and education. This legislation also contains a section dealing with voting rights, but that concern was addressed more substantially by the [[Voting Rights Act of 1965]]. |

===The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964)=== | ===The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964)=== | ||

| Line 312: | Line 312: | ||

* [[Gloria Johnson-Powell]] | * [[Gloria Johnson-Powell]] | ||

* [[Clyde Kennard]] | * [[Clyde Kennard]] | ||

| − | * [[Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.]] | + | * [[Martin Luther King, Jr.|Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.]] |

* [[John Lewis (politician)|John Lewis]] | * [[John Lewis (politician)|John Lewis]] | ||

* [[Viola Liuzzo]] | * [[Viola Liuzzo]] | ||

Revision as of 18:38, 15 November 2006

| African American Portal |

Introduction

The African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968) is viewed by enlightened historians as a revivalistically religious event that had profoundly significant social and political consequences for the United States. The prophetic role played by ordained black clergymen such as the Reverends Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, Joseph Lowery, Wyatt T. Walker, and numerous others, attests to the idea that the driving engine of this movement was its leaders' religious faith, applied strategically to the task of solving America's egregious racial problems. The Christian-faith-based solidarity and self-sacrificial spirit of these black protagonists of racial integration and their white allies supplied them with the inner strength they needed to launch their moral assault upon the immoral system of racial segregation. A biblically-inspired and politically-seismic phenomenon, the Civil Rights Movement of 1955-1968 arose in order to rectify generations worth of injustice, by employing the method of nonviolent resistance against evil, as advocated by the teachings and lifestyle of Jesus of Nazareth.

From its birth in 1776 until the year 1955, the American Experiment had continued for one hundred seventy-nine years, struggling to bring into being a societal and national order that would validate the truth-claims and behavior-claims of the Judeo-Christian faith tradition that lay at the root of America's founding. Finally, in 1955, the forces of historical progress compelled a revolutionary break from the gradualistic pace that had been frustrating and hindering the advancement of social justice and righteousness. The heroic champions of the Civil Rights Movement were thusly raised up by necessity to drive home the message of Jesus's Gospel—that God's love, care, and blessings are to be distributed equally among all humans and are to be shared and enjoyed by everyone, regardless of race, color, language, or social caste.

With the defeat of the Confederate States of America at the end of the Civil War, the nation entered a twelve-year period (1865-1877) known as the Reconstruction. Subsequently, from 1877 through the final decade of the nineteenth century, there came about a massively mushrooming proliferation of racially discriminatory laws and violence targeted at American blacks. Scholars generally agree that this period stands as the nadir of American race relations.

Specifically in the states of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Kansas, there emerged elected, appointed, and/or hired government officials who began to require and/or permit flagrant discrimination by way of various mechanisms. These included (1) racial segregation—upheld by the United States Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896—which was legally mandated, regionally, by the Southern states and nationally at the local level of government; (2) voter suppression or disfranchisement in the Southern states; (3) denial of economic opportunity or resources nationwide; and (4) both private and public acts of terroristic violence aimed at American blacks—violence that was often aided and abetted by government authorities. Although racial discrimination was present nationwide, it was specifically throughout the region of the Southern states that the combination of legally sanctioned bigotry; public and private acts of discrimination; marginalized economic opportunities; and terror directed toward blacks; congealed into a system that came to be identified as Jim Crow.

Because of its direct and relentless attack upon the system and thought of Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement is referred to by some scholars as the Second Reconstruction.

Prior to the Civil Rights Movement of 1955-1968, conventional strategies employed to abolish discrimination against American blacks included efforts at litigation and lobbying by traditional organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). These efforts had been the hallmarks of the American Civil Rights Movement from 1896 to 1954. However, by 1955, due to the policy of "Massive Resistance" displayed by the recalcitrant proponents of racial segregation and voter suppression, conscientious private citizens became dismayed at gradualistic approaches to effectuate desegregation by governmental fiat. In response, civil rights devotees adopted a dual strategy of direct action combined with nonviolent resistance, employing acts of civil disobedience. Such acts served to incite crisis situations between civil rights proponents and governmental authorities. These authorities—at the federal, state, and local levels—typically had to respond with immediate action in order to end the crisis scenarios. And the outcomes were increasingly deemed as favorable to the protesters and their cause. Some of the different forms of civil disobedience employed included boycotts, as successfully practiced by the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956) in Alabama; "sit-ins," as demonstrated by the influential Greensboro sit-in (1960) in North Carolina; and protest marches, as exhibited by the Selma to Montgomery marches (1965) in Alabama.

Noted achievements of the Civil Rights Movement are (1) the legal victory in the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) case that overturned the legal doctrine of "separate but equal" and made segregation legally impermissible; (2) passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, that banned discrimination in employment practices and public accommodations; (3) passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, that safeguarded blacks' sufferage; (4) passage of the Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965, which dramatically changed U.S. immigration policy; and (5) passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 that banned discrimination in the sale and/or rental of housing.

Approaching The Boiling Point: Historical Context and Evolving Thought

Brown vs. Board of Education (1954)

On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision regarding the case dubbed "Brown v. Board of Education" of Topeka (Kansas), in which the plaintiffs charged that the practice of educating black children in public schools totally separated from their white counterparts was unconstitutional. In the court's ruling, it was stated that the "segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group."

In its 9-0 ruling, the Court declared that Plessy v. Ferguson, which established the "separate but equal" practice of segregation, was unconstitutional, and ordered that established segregation be phased out over time.

The Murder of Emmett Till (1955)

Murders of American blacks at the hands of whites were still quite common in the 1950s and still went largely unpunished throughout the South. The murder of Emmett Till—a teenage boy from Chicago, who was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi in the summer of 1955—was different, however. During the pre-dawn hours of August 28th, the youngster was brutally beaten by his two white abductors, who then shot Till and dumped his body in the Tallahatchie River. The boy's age; the nature of his crime (allegedly whistling at a white woman in a grocery store); and his mother's decision to keep the casket open at his funeral, thereby displaying the horrifically savage beating that had been inflicted on her son; all worked to propel into a cause célèbre what might otherwise have been relegated into a routine statistic. As many as 50,000 people may have viewed Till's body at the funeral home in Chicago, and many thousands more were exposed to the evidence of his maliciously unjust slaying when a photograph of his mutilated corpse was published in Jet Magazine.

His two murderers were arrested the day after Till's disappearance. Both were acquitted a month later, after the jury of all white men deliberated for sixty-seven minutes and then issued their "Not Guity" verdict. The murder and subsequent acquittal galvanized Northern public opinion in much the same way that the long campaign to free the "Scottsboro Boys" had done in the 1930s. After being acquitted, the two murderers went on record as blatantly declaring that they were indeed guilty. They remained free and unpunished as a consequence of the judicial procedure known as "Double Jeopardy."

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956)

On December 1, 1955, Mrs. Rosa Parks (the "Mother of the Civil Rights Movement"), while riding on a public bus, refused to relinquish her seat to a white passenger, after being ordered to do so by the bus driver. Mrs. Parks was subsequently arrested, tried, and convicted of disorderly conduct and of violating a local ordinance. After word of this incident reached Montgomery, Alabama's black community, fifty of its most prominent leaders gathered for dialogue, debate, and the strategizing of an appropriate response. They fianlly organized and launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott, to protest the practice of segregating blacks and whites in public transportation. The successful boycott lasted for 382 days (1956 was a Leap Year), until the local ordinance legalizing the segregation of blacks and whites on public buses was vitiated.

Mass Action Replaces Litigation

Thus, after Brown v. Board of Education, the conventionl strategy of courtroom litigation began to shift towards "direct action"—primarily bus boycotts, sit-ins, freedom rides, and similar tactics, all of which relied on mass mobilization, nonviolent resistance, and civil disobedience—from 1955 to 1965. This was, in part, the unintended outcome of the local authorities' attempts to outlaw and harass the mainstream civil rights organizations throughout the Deep South. In 1956, the State of Alabama had effectively barred within its boundaries the operations of the NAACP, by requiring that organization to submit a list of its members, and then proscribing it from all activity when it failed to do so. While the United States Supreme Court ultimately reversed the prohibition, there was a period of a few years in the mid-1950s during which the NAACP was unable to operate. During that span, in June 1956, the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth began the Alabama Christian Movemement for Human Rights (ACMHR) to act as a fill-in. (BCRI)

Churches and other, local, grassroots entities likewise stepped in to fill the gap. They brought with them a much more energetic and broad-based style than the more legalistic approach of groups such as the NAACP.

Quite possibly the most important step forward took place in Montgomery, Alabama, where long-time NAACP activists Rosa Parks and Edgar Nixon prevailed on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956. Activists and black church leaders in other communities, such as Baton Rouge, Louisiana, had used the boycott methodology relatively recently, although these efforts often withered away after a few days. In Montgomery, on the other hand, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was birthed to lead the boycott, and the MIA managed to keep the effort going for more tha a year, until a federal court-order required the city to desegregate its public buses. The triumph in Montgomery propelled Dr. King to nationally-known, luminary status and triggered subsequent bus boycotts, such as the highly successful Tallahassee, Florida boycott of 1956-1957.

As a result of these and other breakthroughs, the leaders of the MIA, Dr. King, and Rev. John Duffy, linked with other church leaders who had led similar boycott efforts (such as Rev. C. K. Steele of Tallahassee and Rev. T. J. Jemison of Baton Rouge; and other activists, such as Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Ella Baker, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and Stanley Levison) to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957. The SCLC, with its headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, did not attempt to create a network of chapters, as did the NAACP, but, instead, offered training and other assistance for local efforts to confront entrenched segregation, while raising funds, mostly from Northern sources, to support these campaigns. It made the philosophy of non-violence both its central tenet and its primary method of challenging systematically condoned racism.

In 1957, Septima Clarke, Bernice Robinson, and Esau Jenkins, with the help of the Highlander Folk School began the first Citizenship Schools on South Carolina's Sea Islands. The goal was to impart literacy to blacks, thereby empowering them to pass voter- elibibility tests. An enormous success, the progarm tripled the number of eligible black voters on St. John Island. The program was then taken over by the SCLC and was duplicated elsewhere.

Prison Reform

Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman (then known as Parchman Farm) is recognized for the infamous part it played in the United States Civil Rights Movement. In the spring of 1961, Freedom Riders (civil rights workers) came to the American South to test the authenticity of desegregation in public facilities. By the end of June, 163 Freedom Riders had been convicted in Jackson, Mississippi. Many were jailed in Parchman.

In 1970, the astute Civil Rights lawyer, Roy Haber, began taking statements from Parchman inmates, which eventually ran to fifty pages, detailing murders, rapes, beatings, and other abuses suffered by the inmates from 1969 to 1971 at Mississippi State Penitentiary. In a landmark case known as Gates v. Collier, 1972, four inmates represented by Haber sued the superintendent of Parchman Farm for violation of their rights under the United States Constitution. Federal Judge William C. Keady found in favor of the inmates, writing that Parchman Farm violated the civil rights of the inmates by inflicting cruel and unusual punishment. He ordered an immediate end to all unconstitutional conditions and practices. Racial segregation of inmates was abolished, as was the "trustee system," which had enabled certain inmates (i.e., "Lifers") to be armed with rifles and to have power and control over other prisoners.

The penitentiary was renovated in 1972, after the excoriating decision by Judge Keady, in which he wrote that the prison was an affront to 'modern standards of decency'. In addition to the extirpation of the "trustee system," the facility was made fit for human habitation.[1]

Desegregating Little Rock (1957)

Following the Supreme Court's decision in Brown, the Little Rock, Arkansas school board voted in 1957 to integrate the school system. The NAACP had chosen to press for integration in Little Rock, rather than in the Deep South, because Arkansas was considered a relatively progressive Southern state. A crisis erupted, however, when Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard on September 4, to prevent the enrollment into Little Rock's Central High School of the nine American black students who had sued for the right to attend a "whites-only" facility. On the opening day of the school term, only one of the nine students showed up, because she did not receive the phone call warning of the danger of going to school. She was harassed by whites at the school grounds, and the police had to whisk her away to safety in a patrol car. Following this, the nine black students had to carpool to the campus and had to be escorted by military personnel in jeeps.

Faubus himself was not a dyed-in-the-wool segregationist, but after his previous year's indication that he would investigate bringing Arkansas into compliance with the Brown decision, he had been significantly pressured to rescind that promise by the more conservative wing of the Arkansas Democrat Party, which controlled politics in that state at the time. Under duress, Faubus took his stand against integration and against the federal court order that required it.

Faubus's rescission set him on a collision course with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was determined to enforce the Federal courts' orders, his own ambivalence and lukewarmness on the issue of school desegregation notwithstanding. Eisenhower federalized the National Guard and ordered them to return to their barracks. The President then deployed elements of the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to protect the students.

The nine students were able to attend classes, although they had to pass through a gauntlet of spitting, jeering whites to take their seats on their first day and had to endure harassment from fellow students for the entire year.

Sit-Ins and Freedom Rides

Sit-Ins

The Civil Rights Movement received an infusion of energy when students in Greensboro, North Carolina; Nashville, Tennessee; and Atlanta, Georgia, began to "sit-in" at the lunch counters of a few of their local stores, to protest those establishments' refusal to desegregate. These protesters were encouraged to dress professionally, to sit quietly, and to occupy every other stool so that potential white sympathizers could join in. Many of these sit-ins provoked local authority figures to use brute force in physically escorting the demonstrators from the lunch facilities.

The "sit-in" technique was not new—the Congress of Racial Equality had used it to protest segregation in the Midwest in the 1940s—but it brought national attention to the movement in 1960. The success of the Greensboro sit-in led to a rash of student campaigns throughout the South. Probably the best organized, most highly disciplined, the most immediately effective of these was in Nashville, Tennessee. By the end of 1960, the sit-ins had spread to every Southern and border state and even to Nevada, Illinois, and Ohio. Demonstrators focused not only on lunch counters but also on parks, beaches, libraries, theaters, museums, and other public places. Upon being arrested, student demonstrators made "jail-no-bail" pledges, to call attention to their cause and to reverse the cost of protest, thereby saddling their jailers with the financial burden of prison space and food.

Freedom Rides

In April of 1960, the activists who had led these sit-ins formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to take these tactics of nonviolent confrontation further. Their first campaign, in 1961, involved conducting freedom rides, in which activists traveled by bus through the deep South, to desegregate Southern bus companies' terminals, as required by federal law. CORE's leader, James Farmer, supported the freedom-rides idea, but, at the last minute, he backed out of actually participating.

The freedom rides proved to be an enormously dangerous mission. In Anniston, Alabama, one bus was firebombed, its passengers forced to flee for their lives. In Birmingham—where an FBI informant reported that Public Safety Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor had encouraged the Ku Klux Klan to attack an incoming group of freedom riders "until it looked like a bulldog had got a hold of them"—the riders were severely beaten. In eerily quiet Montgomery, a mob charged another busload of riders, knocking John Lewis unconscious with a crate and smashing Life photographer Don Urbrock in the face with his own camera. A dozen men surrounded Jim Zwerg, a white student from Fisk University, and beat him in the face with a suitcase, knocking out his teeth.

The freedom riders did not fare much better in jail, where they were crammed into tiny, filthy cells and were sporadically beaten. In Jackson, Mississippi, some male prisoners were forced to do hard labor in 100-degree heat. Others were transferred to Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, where their food was deliberately oversalted and their mattresses were removed. Sometimes the men were suspended from the walls by "wrist breakers". Typically, the windows of their cells were tightly shut on hot days, making it hard for them to breathe.

The student movement involved such celebrated figures as John Lewis, the single-minded activist who "kept on" despite many beatings and harassments; James Lawson, the revered "guru" of nonviolent theory and tactics; Diane Nash, an articulate and intrepid public champion of justice; Bob Moses, pioneer of voting registration in Mississippi the most rural—and most dangerous—part of the South; and James Bevel, a fiery preacher and charismatic organizer and facilitator. Other prominent student activists were Charles McDew; Bernard Lafayette; Charles Jones; Lonnie King; Julian Bond (associated with Atlanta University); Hosea Williams (associated with Brown Chapel); and Stokely Carmichael, who later changed his name to Kwame Ture.

Organizing in Mississippi

In 1962, Robert Moses, SNCC's representative in Mississippi, brought together the civil rights organizations in that state—SNCC, the NAACP, and CORE—to form COFO, the Council of Federated Organizations. Mississippi was the most dangerous of all the Southern states, yet Moses, Medgar Evers of the NAACP, and other local activists embarked on door-to-door voter education projects in rural areas, determined to recruit students to their cause. Evers was assassinated the following year.

While COFO was working at the grassroots level in Mississippi, Clyde Kennard attempted to enter the University of Southern Mississippi. He was deemed a racial agitator by the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, was convicted of a crime he didn't commit, and was sentenced to seven years in jail. He served three, and then was freed, but only because he had intestinal cancer and the Mississippi government didn't want him to die in prison. Two years later, James Meredith was successfully suing for admission to the University of Mississippi. He won that lawsuit in September 1962, and attempted to enter the campus on September 20, on September 25, and again on September 26, 1962, only to be blocked by Mississippi Governor Ross R. Barnett, who proclaimed that "No school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your Governor." After the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals held both Barnett and Lieutenant Governor Paul B. Johnson, Jr. in contempt, with fines of more than $10,000 for each day they refused to allow Meredith to enroll, Meredith, escorted by a force of U.S. Marshals, entered the campus on September 30, 1962.

White students and non-students began rioting that evening, first throwing rocks at the U.S. Marshals who were guarding Meredith at Lyceum Hall, and then firing on the marshals. Two persons, including a French journalist, were killed, 28 marshals suffered gunshot wounds and 160 others were injured. After the Mississippi Highway Patrol withdrew from the campus, President Kennedy sent the regular Army to the campus to quell the uprising. Meredith was able to begin classes the following day, after the troops arrived.

The Albany Movement (1961-1967)

In November 1961, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which had been criticized along with other mainstream civil rights organizations by some student activists for its failure to participate more fully in the freedom rides, committed much of its prestige and resources to a desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia. Dr. King, who had been bitterly aspersed by some SNCC activists for his distance from the dangers that local organizers faced—and subsequently dubbed with the derisive nickname "De Lawd"—intervened personally to assist the campaign led by both SNCC organizers and local leaders.

The campaign was a failure due to the wiley tactics of Laurie Pritchett, the local police chief. He successfully contained the movement without wreaking the sort of violent attacks on demonstrators that inflamed national opinion, and that sparked outcries from within the black community. Prichett also contacted every prison and jail within 60 miles of Albany and arranged for arrested demonstrators to be taken to one of these facilities, allowing plenty of room to remain in his own jail. In addition to these arrangements, Prichett also deemed King's presence as a threat, and forced the leader's release to avoid his rallying the black community. King departed in 1962 without achieving any dramatic victories. The local movement, however, continued the struggle and achieved significant gains over the next few years.

The Birmingham Campaign (1963-1964)

The Albany movement, however, eventually proved to have been an important education for the SCLC, when the organization undertook its Birmingham Campaign in 1963. This effort focused on one short-range goal—the desegregation of Birmingham's downtown business enterprises—rather than on total desegregation, as in Albany. It was also helped by the brutal response of local authorities, that in particular of Eugene "Bull" Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety, who had lost a recent election for mayor to a less rabidly segregationist candidate, but refused to accept the new mayor's authority.

The campaign employed a variety of nonviolent confrontation tactics, including sit-ins, kneel-ins at local churches, and a march to the county building to designate the beginning of a drive to register voters. The City, however, obtained an injunction, barring all such protests. Convinced that the order was unconstitutional, the campaign defied it and prepared for mass arrests of its supporters. Dr. King elected to be among those arrested on April 12, 1963.

While in jail, King, on April 16, penned his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail on the margins of a newspaper, since he had not been granted any writing paper by jail authorities during his solitary confinement. Supporters, meanwhile, pressured the Kennedy administration to intervene and obtain King's release or, at the least, better conditions. King was eventually allowed to call his wife, who was recuperating at home after the birth of their fourth child, and he was finally released on April 19.

The campaign, however, was faltering at this time, as the movement was running out of demonstrators who were willing to risk being jailed. SCLC organizers came up with a bold and highly controversial alternative: calling on high school students to take part in the protest activity. When more than a thousand students walked out of school on May 2, to join the demonstrations in what would come to be called the Children's Crusade, more than six hundred ended up in jail. This was newsworthy, but during this initial encounter the police acted with restraint. On the next day, however, another thousand students gathered at the church, and Bull Connor unleashed vicious police dogs on them. He then mercilessly turned the city's fire hoses—which were set at a level that would peel bark from a tree or separate bricks from mortar—directly on the children. Television cameras broadcasted to the nation the scenes of battering-ram water spouts knocking down defenseless schoolchildren and of dogs attacking unarmed individual demonstrators.

The resultant, widespread, public outrage impelled the Kennedy administration to intervene more forcefully in the negotiations between the white business community and the SCLC. On May 10, 1963, the parties declared an agreement to desegregate the lunch counters and other public accommodations downtown; to create a committee to eliminate discriminatory hiring practices; to arrange for the release of jailed protesters; and to establish regular means of communication between black and white leaders.

Not everyone in the black community approved of the agreement. Fred Shuttlesworth was particularly critical, since he had accumulated a great deal of skepticism about the good faith of Birmingham's power structure from his experience in dealing with them. The reaction from certain parts of the white community was even more violent. The Gaston Motel, which housed the SCLC's unofficial headquarters, was bombed, as was the home of Dr. King's brother, the Reverend A. D. King. Kennedy prepared to federalize the Alabama National Guard, but did not follow through. Four months later, on September 15, Ku Klux Klan members bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church (see 16th Street Baptist Church bombing) in Birmingham, killing four young girls.

Other events of the summer of 1963 were as follows: On June 11, 1963, George Wallace, Governor of Alabama, attempted to block the integration of the University of Alabama. President John F. Kennedy dispatched enough force to make Governor Wallace step aside, thereby allowing the enrollment of two black students. That evening, JFK addressed the nation via TV and radio with an historic civil rights speech.[2] The next day, in Mississippi, Medgar Evers was assassinated.[3] The following week, as promised, on June 19, 1963, JFK submitted his Civil Rights bill to Congress.[4]

The March on Washington (1963)

Back in 1941, A. Philip Randolph had planned a March on Washington, in support of demands for the elimination of employment discrimination in defense industries. He called off the march when the Roosevelt administration met that demand by issuing Executive Order 8802, barring racial discrimination and creating an agency to oversee compliance with the Order.

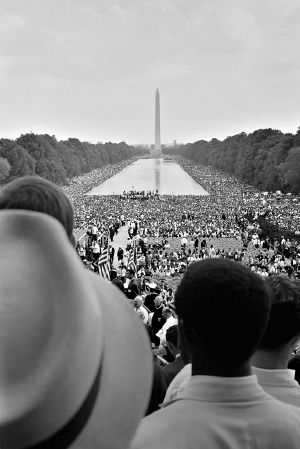

Randolph and Bayard Rustin were the chief planners of the second March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which they proposed in 1962. The Kennedy administration vigorously pressured Randolph and King to call it off, but to no avail. The march was held on August 28, 1963.

Unlike the planned 1941 march, for which Randolph included only black-led organizations on the agenda, the 1963 March was a collaborative effort of all of the major civil rights organizations, the more progressive wing of the labor movement, and other liberal groups. The March had six official goals: "meaningful civil rights laws; a massive federal works program; full and fair employment; decent housing; the right to vote; and adequate integrated education." Of these, the March's central focus was on passage of the civil rights bill that the Kennedy administration had proposed after the upheavals in Birmingham.

The March was a stunning success, although not without controversy. More than 200,000 demonstrators gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial, where King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. While many of the rally's speakers applauded the Kennedy Administration for the (largely ineffective) efforts it had made toward obtaining new, more effective civil rights legislation to protect voting rights and to outlaw segregation, John Lewis of SNCC took the Administration to task for how little it had done to protect Southern blacks and civil rights workers under attack in the Deep South. While he toned down his comments under pressure from others in the movement, his words still stung:

We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of, for hundreds and thousands of our brothers are not here—for they have no money for their transportation, for they are receiving starvation wages…or no wages at all. In good conscience, we cannot support the administration's civil rights bill.

This bill will not protect young children and old women from police dogs and fire hoses when engaging in peaceful demonstrations. This bill will not protect the citizens of Danville, Virginia, who must live in constant fear in a police state. This bill will not protect the hundreds of people who have been arrested on trumped-up charges like those in Americus, Georgia, where four young men are in jail, facing a death penalty, for engaging in peaceful protest.

I want to know: which side is the federal government on? The revolution is a serious one. Mr. Kennedy is trying to take the revolution out of the streets and put it in the courts. Listen Mr. Kennedy, the black masses are on the march for jobs and for freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won't be a 'cooling-off period'.

After the march, King and other civil rights leaders met with President Kennedy at the White House. While the Kennedy administration appeared to be sincerely committed to passing the bill, it was not clear that it had the votes to do so. But when President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963,[4] the new President, Lyndon Johnson, decided to, and did, assert his power in Congress to effect a great deal of JFK's legislative agenda in 1964 and 1965, much to the public's approval.

Mississippi Freedom Summer (1964)

In Mississippi, during the summer of 1964 ("Freedom Summer"), the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) used its resources to recruit more than one hundred college students, many from outside the state, to join with local activists in registering voters; teaching at "Freedom Schools"; and organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. The work was still as dangerous as ever, and on June 21, three civil rights workers (James Chaney, a young black Mississippian and plasterer's apprentice; Andrew Goodman, a white anthropology student from Queens College; and Michael Schwerner, a white social worker from Manhattan's Lower East Side) were all abducted and murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan, among whom were deputies of the Neshoba County sheriff's department.

The disappearance of the three men sparked a national uproar. What followed was a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) inquiry, although President Johnson had to use indirect threats of political reprisals against J. Edgar Hoover, to force the indifferent Bureau Director to actually conduct the investigation. After bribing at least one the murderers for details regarding the crime, the FBI found the victims' bodies on August 4, in an earthen dam on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Mississippi. Schwerner and Goodman had been shot once. Chaney, the lone black, had been savagely beaten and shot three times. During the course of that investigation, the FBI also discovered the bodies of a number of other Mississippi blacks whose disappearances had been reported over the past several years without arousing any interest or concern beyond their local communities.

The disappearance of these three activists remained on the public interest frontburner for the entire month and-a-half until their bodies were found. Johnson used both the outrage over their deaths and his redoubtable political skills to bring about the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bars discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and education. This legislation also contains a section dealing with voting rights, but that concern was addressed more substantially by the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964)

COFO had held a Freedom Vote in Mississippi in 1963 to demonstrate the desire of black Mississippians to vote. More than 90,000 people voted in mock elections which pitted candidates from the "Freedom Party" against the official state Democratic party candidates. In 1964, organizers launched the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the all-white slate from the state party. When Mississippi voting registrars refused to recognize their candidates, they held their own primary, selecting Fannie Lou Hamer, Annie Devine, and Victoria Gray to run for Congress and a slate of delegates to represent Mississippi at the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

Their presence in Atlantic City, New Jersey, was very inconvenient, however, for the convention organizers, who had planned a triumphal celebration of the Johnson Administration’s achievements in civil rights, rather than a fight over racism within the Democratic Party itself. Johnson also was worried about the inroads that Barry Goldwater’s campaign was making in what previously had been the Democratic stronghold of the "Solid South" and the support that George Wallace had received during the Democratic primaries in the North. Other all-white delegations from other southern states had threatened to walk out if the all-white slate from Mississippi were not seated.

Johnson could not, however, prevent the MFDP from taking its case to the Credentials Committee, where Fannie Lou Hamer testified eloquently about the beatings that she and others were given and the threats they faced for trying to register to vote. Turning to the television cameras, Hamer asked, "Is this America?"

Johnson attempted to preempt coverage of Hamer's testimony by calling a hastily scheduled speech of his own. When that failed to move the MFDP off the evening news, he offered the MFDP a "compromise" under which it would receive two non-voting, at-large seats, while the white delegation sent by the official Democratic Party would retain its seats. The MFDP angrily rejected the compromise. As Aaron Henry, Medgar Evers' successor as President of the NAACP 's Mississippi affiliate, stated:

"Now, Lyndon made the typical white man's mistake: Not only did he say, 'You've got two votes,' which was too little, but he told us to whom the two votes would go. He'd give me one and Ed King one; that would satisfy. But, you see, he didn't realize that sixty-four of us came up from Mississippi on a Greyhound bus, eating cheese and crackers and bologna all the way there; we didn't have no money. Suffering the same way. We got to Atlantic City; we put up in a little hotel, three or four of us in a bed, four or five of us on the floor. You know, we suffered a common kind of experience, the whole thing. But now, what kind of fool am I, or what kind of fool would Ed have been, to accept gratuities for ourselves? You say, Ed and Aaron can get in but the other sixty-two can't. This is typical white man picking black folks' leaders, and that day is just gone."

Hamer put it even more succinctly:

"We didn't come all the way up here to compromise for no more than we’d gotten here. We didn't come all this way for no two seats, 'cause all of us is tired."

The MFDP kept up its agitation within the convention, however, even after it was denied official recognition. When all but three of the "regular" Mississippi delegates left because they refused to pledge allegiance to the party, the MFDP delegates borrowed passes from sympathetic delegates and took the seats vacated by the Mississippi delegates, only to be removed by the national party. When they returned the next day to find that convention organizers had removed the empty seats that had been there the day before, they stayed to sing freedom songs.

The 1964 convention disillusioned many within the MFDP and the Civil Rights Movement, but it did not destroy the MFDP itself. The MFDP became more radical after Atlantic City, inviting Malcolm X to speak at its founding convention and opposing the war in Vietnam.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his above-mentioned work for peace, December 10 1964.[5]

Selma and the Voting Rights Act (1965)

SNCC had undertaken an ambitious voter registration program in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, but made little headway in the face of opposition from Selma's sheriff, Jim Clark. After local residents asked the SCLC for assistance, King came to Selma to lead a number of marches, at which he was arrested along with 250 other demonstrators. The marchers continued to meet violent resistance from police. A Selma resident, Jimmie Lee Jackson was killed by police at a later march in February.

On March 7, Hosea Williams of the SCLC and John Lewis of SNCC led a march of 600 people who intended to walk the 54 miles from Selma to the state capital in Montgomery. Only six blocks into the march, however, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, state troopers and local law enforcement, some mounted on horseback, attacked the peaceful demonstrators with billy clubs, tear gas, rubber tubes wrapped in barbed wire and bull whips, driving them back into Selma. John Lewis was knocked unconscious and dragged to safety, while at least 16 other marchers were hospitalized. Among those gassed and beaten was Amelia Boynton Robinson, who was at the center of civil rights activity at the time.

The national broadcast of the footage of lawmen attacking unresisting marchers seeking only the right to vote provoked a national response similar to the scenes from Birmingham two years earlier. While the marchers were able to obtain a court order permitting them to make the march without incident two weeks later, local whites murdered another voting rights supporter, Rev. James Reeb after a second march to the site of Bloody Sunday on March 9. He died in a Birmingham hospital March 11. Four Klansmen shot and killed Detroit homemaker Viola Liuzzo March 25 as she drove marchers back to Selma at night after the successful completed march to Montgomery.

Johnson delivered a televised address to Congress eight days after the first march in support of the voting rights bill he had sent to Congress. In it he stated:

But even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life.

Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.

Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on August 6. The 1965 Act suspended poll taxes, literacy tests and other voter tests and authorized federal supervision of voter registration in states and individual voting districts where such tests were being used. African-Americans who had been barred from registering to vote finally had an alternative to the courts. If voting discrimination occurred, the 1965 Act authorized the Attorney General of the United States to send federal examiners to replace local registrars. Johnson reportedly stated to associates that signing the bill had lost the South for the Democratic Party for the foreseeable future.

The Act, however, had an immediate and positive impact for African-Americans. Within months of its passage on August 6, 1965, one quarter of a million new black voters had been registered, one third by federal examiners. Within four years, voter registration in the South had more than doubled. In 1965, Mississippi had the highest black voter turnout—74%—and led the nation in the number of black public officials elected. In 1969, Tennessee had a 92.1% turnout; Arkansas, 77.9%; and Texas, 73.1%.

Several Whites who opposed the voting rights act paid an immediate price as well. Sheriff Jim Clark of Mississippi who was infamous for using fire hoses and cattle prods to counteract civil rights marches was up for reelection in 1966. Taking off the notorious "Never" pin on his uniform to get the Black portion of the vote, he was unsuccessful. At the election poll, he lost as Blacks voted for the sake of just taking him out of office by any means possible.

Blacks winning the right to vote changed the political landscape of the South forever. When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, barely 100 African-Americans held elective office in the U.S.; by 1989, there were more than 7,200, including more than 4,800 in the South. Nearly every Black Belt county in Alabama had a black sheriff, and southern blacks held top positions within city, county, and state governments. Atlanta had a black mayor, Andrew Young, as did Jackson, Mississippi—Harvey Johnson—and New Orleans, with Ernest Morial. Black politicians on the national level included Barbara Jordan, who represented Texas in Congress, and former mayor Young, who was appointed U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations during the Carter Administration. Julian Bond was elected to the Georgia Legislature in 1965, although political reaction to his public opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam prevented him from taking his seat until 1967. John Lewis currently represents Georgia's 5th Congressional District in the United States House of Representatives, where he has served since 1987. Lewis sits on the House Ways and Means and Health committees.

The American Jewish Community and the Civil Rights Movement

Many in the American Jewish community supported the Civil Rights Movement. The Jewish philanthropist Julius Rosenwald funded dozens of primary schools, secondary schools and colleges for black youth. He gave, and led the Jewish community in giving to, some 2,000 schools for black Americans. This list includes Howard, Dillard and Fisk universities. At one time some forty percent of southern blacks were learning at these schools.[citation needed] Fifty percent of the civil rights lawyers who worked in the south, were Jewish.[citation needed]

Leaders of the Reform Movement were arrested with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1964 after a challenge to racial segregation in public accommodations. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched arm-in-arm with Dr. King in the 1965 March on Selma. Source: Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, Civil Rights

Abraham Joshua Heschel, a writer, rabbi and professor of theology at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America was outspoken on the subject of civil rights and marched arm-in-arm with Dr. King in Selma.

The PBS television show From Swastika to Jim Crow explores Jewish involvement in the civil rights movement, demonstrating that Jewish professors, refugees from the Holocaust came to teach at Southern Black Colleges in the 1930s and '40s. There came to be empathy and collaboration between Blacks and Jews. Professor Ernst Borinski organized dinners at which blacks and whites sat next to each other, a simple act that challenged segregation. Black students empathized with the cruelty these scholars had endured in Europe.[6]

The American Jewish Committee, American Jewish Congress, and Anti-Defamation League actively promoted civil rights.

Fraying of Alliances

King reached the height of popular acclaim during his life in 1964, when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. His career after that point was filled with frustrating challenges, as the liberal coalition that had made the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 began to fray.

King was, by this point, becoming more estranged from the Johnson administration, breaking with it in 1965 by calling for peace negotiations and a halt to the bombing of Vietnam. He moved further left in the following years, moving towards socialism and speaking of the need for economic justice and thoroughgoing changes in American society beyond the granting of the civil rights that the movement had sought to that date.

King's attempts to broaden the scope of the Civil Rights Movement were halting and largely unsuccessful, however. King made several efforts in 1965 to take the Movement north to address issues of employment and housing discrimination. His campaign in Chicago failed, as Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley marginalized King's campaign by promising to "study" the city's problems. In 1966, white demonstrators holding "white power" signs in then notoriously racist Cicero, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, threw stones at King and other marchers demonstrating against housing segregation, injuring King.

Race Riots (1963-1970)

Throughout the Civil Rights Movement, many acts were signed into legislation guaranteeing equality for black citizens. Enforcement of these acts, especially in Northern cities was another issue altogether. After World War II, more than half of the country's black population lived in Northern and Western cities rather than Southern rural areas. Coming to these cities for better job opportunities and a lack of legal segregation, blacks often did not receive the lifestyle that they had come for.

While blacks were free from segregation and terror at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, other problems often presided. Urban black neighborhoods were in fact amongst the worst and poorest in any major city. These neighborhoods were ghettos rampant with unemployment and crime. Blacks rarely owned any neighborhood stores or businesses, and often worked menial or blue-collar jobs for a fraction of the pay that their white co-workers received. Blacks often made only enough money to live in the most dilapidated housing or public housing. Blacks often also were eligible for welfare, being unable to find a well paying job. The use of illegal drugs such as cocaine and heroin was out of control in black neighborhoods before large-scale numbers of whites ever began experimenting with them. Liquor stores were also in abundance, adding to the lack of opportunity for blacks that was in place. Blacks attended schools that were often the worst academically in the city and had very few white students inside of them. Worst of all, black neighborhoods were subject to police problems that white neighborhoods were not at all accustomed to dealing with. The police forces in America were set up with the motto "To Protect and Serve." Rarely did this occur in any black neighborhoods. Rather, many Blacks felt police only existed to "Patrol and Control." The racial makeup of the police departments, usually largely white, was a huge factor here. Up until 1970, no urban police force in America was greater than 10% black, and in most black neighborhoods, blacks accounted for less than 5% of the police on patrol. Arrests merely for being black were common, and as a result of racist police harassment and all the other listed factors causing a poor living standard, rioting eventually broke out.

One of the first major race riots took place in Harlem, New York, in the summer of 1964. A white Irish-American police officer named Thomas Gilligan shot a 15-year-old black named James Powell for allegedly charging at him with a knife. In fact, Powell was unarmed and as a result, an angry mob approached the precinct station house and demanded Gilligan's suspension. When it was refused, many local stores were ransacked. Even though this precinct had promoted the NYPD's first black station commander, the neighborhood people were tired of the inequalities in place, and were so enraged that they looted and burned anything that was not black-owned in the neighborhood. This riot later spread to Bedford-Stuyvesant, the main black neighborhood in Brooklyn, and during that same summer, riots broke out also in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for similar reasons.

The following year, 1965 President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, but conditions for blacks had not improved for several neighborhoods. This time, in the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, another riot broke out. Watts, like Harlem, was subject to impoverished living conditions where unemployment and drugs were rampant and the neighborhood was subject to the patrol of a largely white police department. The police, who were arresting a young man for drunk driving, argued with the suspect's mother before onlookers. The result was a massive destruction of property which lasted six days. Thirty-four people were killed and property valued at about $30 million was destroyed, making the Watts riot one of the worst in American history.

With black militancy on the rise, several acts of anger were now directed at the police. Black residents growing tired of police brutality continued to riot and even began to join groups such as the Black Panthers solely to rid their neighborhoods of oppressive white police officers. Now, blacks had not only began rioting but also began murdering white police who were believed to be racist and brutal, while shouting words such as "honky" and "pig" towards the officers.

Rioting continued through 1966 and 1967 in cities such as Atlanta, San Francisco, Baltimore, Newark, Chicago, Brooklyn, and worst of all in Detroit. In Detroit, several blacks had previously received jobs in automobile assembly lines, so a comfortable black middle class was living well. However, all the blacks who had not moved upward were living in even worse conditions subject to the same problems as blacks in Watts and Harlem. When white police officers murdered a black pimp and brutally shut down an illegal bar on a liquor raid, black residents got extremely angered and began a new riot. The Detroit riot was so bad that it was one of the first major cities where whites began to leave in a sense of "white flight" because the riot seemed threatening enough to burn down white neighborhoods as well. Cities such as Detroit, Newark, and Baltimore now have a less than 40% White population as a result of these riots. To this day, these cities contain some of the worst living conditions for blacks anywhere in America.

Fresh rioting broke out in April 1968 after Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered, allegedly, by white supremacist, James Earl Ray. This time riots broke out simultaneously in every major metropolis, but the cities that were burned the worst included Chicago, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C.. As a result of the numerous riots, President Johnson had created the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders in 1967. The commission's final report called for major reforms in employment practices and for public assistance to be targeted to black communities everywhere. An alarm went forth stating that the United States was moving toward separate and unequal white and black societies.

Affirmative Action helped in the hiring process of more black police officers in every major city, and as a result, blacks make up a majority of the police departments in cities such as Baltimore, Washington, New Orleans, Atlanta, Newark, and Detroit. While many are glad at this development, many criticize the hiring of these officers as a method of appeasement and covering up racism at the hands of the police departments. Employment discrimination in modern times is less of a problem but still at times happens. Illegal drugs are still rampant in black neighborhoods, but statistics now show that whites are as likely if not more so to experiment than blacks. Overall, improvements have been made in every city affected by these riots, but work is still to be done so that inequality can one day maybe disappear completely.

Black Power (1966)

At the same time King was finding himself at odds with factions of the Democratic Party, he was facing challenges from within the Civil Rights Movement to the two key tenets upon which the movement had been based: integration and non-violence. Black activists within SNCC and CORE had chafed for some time at the influence wielded by white advisors to civil rights organizations and the disproportionate attention that was given to the deaths of white civil rights workers while black workers' deaths often went virtually unnoticed. Stokely Carmichael, who became the leader of SNCC in 1966, was one of the earliest and most articulate spokespersons for what became known as the "Black Power" movement after he used that slogan, coined by activist and organizer Willie Ricks, in Greenwood, Mississippi on June 17, 1966.

In 1966 SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael also took Black Power to another level. He urged African American communities to confront the white supremacist group known as the Ku Klux Klan armed and ready for battle because he felt it was the only way to ever rid the communities of the terror caused by the Klan. Listening to this, several Blacks confronted the Ku Klux Klan armed and as a result the Klan stopped terrorizing their communities.

Several people engaging in the Black Power movement started to gain more of a sense in Black pride and identity as well. In gaining more of a sense of a cultural identity, several Blacks demanded that Whites no longer refer to them as "Negroes" but as "Afro-Americans." Up until the mid-1960s, Blacks had dressed similarly to whites and combed their hair straight. As a part of gaining a unique identity, Blacks now started to wear loosely fit Dashikis which were a multi-colored African clothing and had started to grow their hair out as a natural Afro. The Afro sometimes nicknamed the 'fro remained a popular black hairstyle until the late 1970s.

Black Power was made most public however by the Black Panther Party which founded in Oakland, California in 1966. This group followed ideology stated by Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam using a "by-any-means necessary" approach to stopping inequality. They sought to rid African American neighborhoods of Police Brutality and had a ten-point plan amongst other things. Their dress code consisted of leather jackets, berets, light blue shirts, and an Afro hairstyle. They are best remembered for setting up free breakfast programs, referring to white police officers as "pigs", displaying shotguns and a black power fist, and often using the statement of "Power to the people."

Black Power was taken to another level inside of prison walls. In 1966, George Jackson formed the Black Guerilla Family in the California prison of San Quentin. The goal of this group was to overthrow the White ran government in America and the prison system in general. This group also preaches the general hatred of Whites and Jews everywhere. In 1970, this group displayed their ruthlessness after a White prison guard was found not guilty for shooting three black prisoners from the prison tower. The guard was found murdered in pieces and a message of how serious the group is was heard throughout the whole prison. This group also masterminded the 1971 Attica riot in New York which led to a takeover of the Attica prison. To this day, the Black Guerilla Family is one of the most feared and infamous advocates of Black Power behind prison walls.

Also in 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, while being awarded the gold and bronze medals, respectively, at the 1968 Summer Olympics, donned human rights badges and each raised a black-gloved Black Power salute during their podium ceremony. Incidentally, it was the suggestion of white silver medalist, Peter Norman of Australia, for Smith and Carlos to each wear one black glove. Smith and Carlos were immediately ejected from the games by the USOC, and later the IOC issued a permanent lifetime ban for the two. However, the Black Power movement had now been given a stage on live, international television.

King was not comfortable with the "Black Power" slogan, which sounded too much like black nationalism to his ears. SNCC activists, in the meantime, began embracing the "right to self-defense" in response to attacks from white authorities, and booed King for continuing to advocate non-violence. When King was murdered in 1968, Stokely Carmichael stated that Whites murdered the one person who would prevent rampant rioting and burning of major cities down and that Blacks would now burn every major city to the ground. In every major city from Boston to San Francisco, racial riots broke out in the Black community following King's death and as a result, "White Flight" occurred from several cities leaving Blacks in a dilapidated and nearly unrepairable city.

Memphis and the Poor People's March (1968)

Rev. James Lawson invited King to Memphis, Tennessee, in March, 1968, to support a strike by sanitation workers who had launched a campaign for union representation after two workers accidentally were killed on the job. A day after delivering his famous "Mountaintop" sermon at Lawson's church, King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. Riots broke out in over 110 cities across the United States in the days that followed, notably in Chicago, Baltimore, and in Washington, D.C.

Rev. Ralph Abernathy succeeded King as the head of the SCLC and attempted to carry forth King's plan for a Poor People's March, which would have united blacks and whites to campaign for fundamental changes in American society and economic structure. The march went forward under Abernathy's plainspoken leadership, but is widely regarded as a failure.

Gates vs. Collier

Gates vs. Collier was a case decided in federal court that brought an end to the trustee system and flagrant inmate abuse and racial segregation at Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, Mississippi.

In 1972 federal judge, William C. Keady found that Parchman Farm violated modern standards of decency. He ordered an immediate end to all unconstitutional conditions and practices. Racial segregation of inmates was abolished. And the trustee system, which allow certain inmates to have power and control over others, was also abolished.[7]

Footnotes

- ↑ Goldman, Robert M. Goldman (April 1997). "Worse Than Slavery": Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice - book review. Hnet-online. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

- ↑ "Radio and Television Report to the American People on Civil Rights," June 11 1963, transcript from the JFK library.

- ↑ Medgar Evers, a worthwhile article, on The Mississippi Writers Page, a website of the University of Mississippi English Department.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Civil Rights bill submitted, and date of JFK murder, plus graphic events of the March on Washington. This is an Abbeville Press website, a large informative article apparently from their book The Civil Rights Movement (ISBN 0-7892-0123-2).

- ↑ MLK's Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech on December 10 1964. This is part of the Nobel Foundation website.

- ↑ PBS website From Swastika to Jim Crow

- ↑ Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

See Also

Template:AfricanAmerican

- Ralph Abernathy

- American Civil Rights Movement (1896-1954)

- American Civil Rights Movement Timeline

- Ella Baker

- Mary Fair Burks

- Congress on Racial Equality

- Annie Devine

- Doris Derby

- Karl Fleming

- James Forman

- Fannie Lou Hamer

- T.R.M. Howard

- Winson Hudson

- Jesse Jackson

- Gloria Johnson-Powell

- Clyde Kennard

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- John Lewis

- Viola Liuzzo

- Robert Parris Moses

- Denise Nicholas

- Gloria Richardson

- Jo Ann Robinson

- Modjeska Monteith Simkins

- Emmett Till

- Malcolm X

- Operation Breadbasket

- Rainbow Coalition

- Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project

- Southern Christian Leadership Conference

- Stokely Carmichael

- Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee

- Urban League

Pro Civil Rights Presidents

Anti Civil Rights Presidents

- Andrew Jackson {Indian Removal Act}

- Martin Van Buren {Indian Removal Act;Amistad case; denyed Congress the right to abolish slavery in Washington DC without consent of slave states}

- Andrew Johnson {Vetoed Civil Rights Legislation and refused funding for Freeman's Bureau}

- Rutherford B. Hayes {Remove Federal Troops from the South when Black Codes were coming in force}

- Chester A Arthur-did not veto the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

- Woodrow Wilson {Segregated Washington D.C}

- Franklin Deleno Roosevelt {Refused to act on a AntiLynching bill; signed the Japanese American Interment Order}

Anti Civil Rights Congressmen

- John C. Calhoun of South Carolina

- Thomas Hart Benton (senator) of Missouri

- Martin Dies Jr of Texas

- James Eastland of Mississippi

- Jesse Helms of North Carolina

- Fritz Hollings of South Carolina

- Henry Laurens of South Carolina

- Edward Rutledge of South Carolina

- John Rutledge of South Carolina

- Samuel R. Thurston of Oregon

- Ben Tillman of South Carolina

Anti Civil Rights Supreme Court Justices

- Roger B. Taney

- James C. McReynolds

- James F. Byrnes

Pro Civil Rights Supreme Court Justices

- Hugo Black

- John Marshall Harlan

- John Marshall Harlan II

- Frank Murphy

External Links

- Watch Documentary: FBI War on Black Americans

- University of Southern Mississippi's Civil Rights Documentation Project, includes an extensive Timeline

- What Was Jim Crow? (The racial caste system that precipitated the Civil Rights Movement)

- Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, Mississippi, Civil Rights sculpture

- History and images of the sit-in movement

- Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project

- "You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow!" PBS documentary on first Freedom Ride, in 1947

- Materials relating to the desegregation of Ole Miss in 1962

- Images of the Civil Rights Movement in Florida from the State Archives of Florida

- At the River I Stand California Newsreel documentary on Civil Rights and labor rights in the 1968 Memphis Sanitation workers' strike. 56 minutes, 1993

- Civil Rights Movement Veterans website bios, photos, and testimony from nearly 300 people who fought for civil rights in the Deep South of the mid-1960s

- The Georgia Movement

- Pamphlet on King, Socialism and their contribution to Racial Equality from the Socialist Party USA (PDF)

- Snapshots in Time: The Public in the Civil Rights Era Examines how public attitudes about civil rights evolved based on opinion surveys taken at the time, from Public Agenda Online

Jewish Community and Civil Rights

- Civil Rights - Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism

- Blacks and Jews Entangled, Edward S. Shapiro, First Things

- 50 years after integration case, Jews remember their crucial role, Chicago Jewish Community

- What Went Wrong? The Creation and Collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance

Further Reading

- Branch, Taylor. At Canaans Edge: America In the King Years, 1965-1968. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0-684-85712-X

- ---. Parting the waters : America in the King years, 1954-1963. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0-671-46097-8

- ---. Pillar of fire : America in the King years, 1963-1965.: Simon & Schuster, 1998. ISBN 0-684-80819-6

- Breitman, George The Assassination of Malcolm X. New York: Pathfinder Press. 1976.

- Eric Foner and Joshua Brown, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. Alfred A. Knopff: New York, 2005, 225-238.

- Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960's. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1980. ISBN 0-374-52356-8.

- Carson, Clayborne; Garrow, David J.; Kovach, Bill; Polsgrove, Carol, eds. Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1941-1963 and Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1963-1973. New York: Library of America, 2003. ISBN 1-931082-28-6 and ISBN 1-931082-29-4.

- Garrow, David J. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. 800 pages. New York: William Morrow, 1986. ISBN 0-688-04794-7.

- Garrow, David J. The FBI and Martin Luther King. New York: W.W. Norton. 1981. Viking Press Reprint edition. February 1, 1983. ISBN 0-14-006486-9. Yale University Press; Revised & Expanded edition. August 1, 2006. ISBN 0-300-08731-4.

- Horne, Gerald The Fire This Time: The Watts Uprising and the 1960's. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. 1995. Da Capo Press; 1st Da Capo Press ed edition. October 1, 1997. ISBN 0-306-80792-0

- Kirk, John A, Martin Luther King, Jr. London: Longman, 2005. ISBN 0-582-41431-8

- Kirk, John A, Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940-1970 Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8130-2496-X

- Kousser, J. Morgan, "The Supreme Court And The Undoing of the Second Reconstruction," National Forum, (Spring 2000).

- Malcolm X (with the assistance of Alex Haley). The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Random House, 1965. Paperback ISBN 0-345-35068-5. Hardcover ISBN 0-345-37975-6.

- Marable, Manning. Race, Reform and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1982. 249 pages. University Press of Mississippi, 1984. ISBN 0-87805-225-9.

- McAdam, Doug. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1982

- Minchin, Timothy J. Hiring the Black Worker: The Racial Integration of the Southern Textile Industry, 1960-1980. 342 pages. University of North Carolina Press. May 1, 1999. ISBN 0-8078-2470-4.

Thesis

- Westheider, James Edward. "My Fear is for You": African Americans, Racism, and the Vietnam War. University of Cincinnati. 1993.

Documentary Films

- Freedom on my Mind, 110 minutes, 1994, Producer/Directors: Connie Field and Marilyn Mulford, 1994 Academy Award Nominee, Best Documentary Feature

- Eyes on the Prize, PBS television series.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.