Great Schism

The Great Schism, also called the East-West Schism, divided Christendom into Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) branches, which then became the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, respectively. Usually dated to 1054, the Schism was the result of an extended period of tension and sometimes estrangement between then Latin and Greek Churches. The break became permanent after the sack of Byzantium Constantinople by Western Christians in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade.

The primary causes of the Great Schism were the dispute over the authority of the Western papacy to make rulings affecting the whole Church, and specifically the Pope's insertion of the filioque clause into the Nicene Creed. Eastern Orthodoxy holds that the primacy of the Patriarch of Rome (the Pope) is one of honor only, and that he does not have the authority to determine policy for other jurisdictions or to change the decisions of Ecumenical Councils. The filioque controversy has to do with a difference between the two Churches on the doctrine of the Trinity; namely, whether the Holy Spirit "proceeds" from the Father alone (the Orthodox position) or from the Father and the Son (the Catholic position). Other catalysts for the Schism included differences over liturgical practices, conflicting claims of jurisdiction, and the relationship of the Church to the Byzantine Christian emperor. After the Great Schism, the Eastern and Western Churches became increasingly split along doctrinal, linguistic, political, liturgical and geographic lines.

Many Christians indicate the sentiment that the Great Schism was a tragic instance of the Christian Church's inability to live up to the "new commandment" of Jesus in John 13:34-35: "A new command I give you: Love one another... By this all men will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another." Among the hundreds of divisions within the Christian movement that have occurred both before and after 1054, it is one of the most tragic.

Serious reconciliation attempts in the twentieth century to heal this breach in the body of Christ have produced several meetings, some theological documents, the removal of mutual excommunications, the return of relics to the East by the Vatican, and the attendance of the head of the Orthodox Church at the funeral of Pope John Paul II, among other steps.

Origins

The Christian Church in the Roman Empire generally recognized the special positions of three bishops, known as patriarchs: the Bishop of Rome, the Bishop of Alexandria, and the Bishop of Antioch; and it was officially regarded as an "ancient custom" by the Council of Nicea in 325. These were joined by the Bishop of Constantinople and by the Bishop of Jerusalem, both confirmed as patriarchates by the Council of Chalcedon in 451. The patriarchs held precedence over fellow bishops in their geographical areas. The Ecumenical Councils of Constantinople and Chalcedon stated that the See of Constantinople should be ranked second among the patriarchates as the "New Rome." However, the Patriarch of Rome strongly disputed that point, arguing that the reason for Rome's primacy had never been based on its location in the Imperial capital, but because of its bishop's position of the successor of Saint Peter, the first-ranking among the Apostles.

Disunion in the Roman Empire contributed to tensions within the Church. Theodosius the Great, who died in 395, was the last emperor to rule over a united Roman Empire. After his death, his territory was divided into western and eastern halves, each under its own emperor. By the end of the fifth century, the Western Roman Empire had been overrun by the Germanic tribes, while the Eastern Roman Empire (known also as the Byzantine Empire) continued to thrive.

Other factors caused the East and West to drift further apart. The dominant language of the West was Latin, while that of the East was Greek. Soon after the fall of the Western Empire, the number of individuals who spoke both Latin and Greek began to dwindle, and communication between East and West grew much more difficult. With linguistic unity gone, cultural unity began to crumble as well.

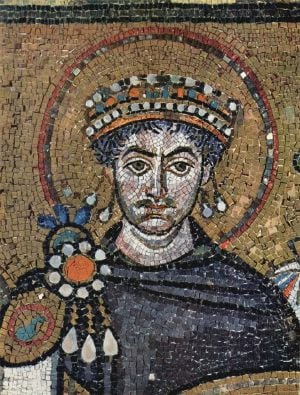

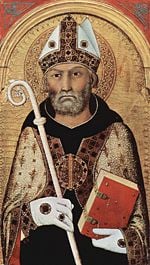

The two halves of the Church were naturally divided along similar lines; they developed different rites and had different approaches to religious doctrines. The Eastern Church tended to be more mystically oriented, while the Western Church developed an effective administrative apparatus. The East used the Septuagint Greek translation of the Old Testament, while the West accepted portions of the Hebrew text as well as portions of the Septuagint. The highly logical writings of Saint Augustine greatly influenced the West, but more mystically oriented writers tend to predominate in the East. Augustinian theology, with its doctrine of Original Sin and human depravity, was more pessimistic about the role of the state in relation to the church, while the Eastern Church, especially after the time of Justinian the Great, developed the doctrine of harmonia, according to which the church was less likely to oppose the emperor. Although the Great Schism was still centuries away, its outlines were already perceptible.

Preliminary schisms

Two temporary schisms between Rome and Constantinople anticipated the final Great Schism. The first of this, lasting from 482 to 519 C.E., is known in the West as the Acacian Schism. It involved a conflict between Ecumenical Patriarch Acacius and Pope Felix III. Acacius advised the Byzantine Emperor Zeno, in an effort to quell the Nestorian heresy, to tolerate the Monophysites, thus ignoring the Chalcedonian formula in which both of these theological positions were condemned. Felix III condemned and "deposed" Acacius, although his decree had no practical effect on him. The schism lasted until well after Acasius' death, under the reigns of the Emperor Justin I and Pope Hormisdas in 519.

The second schism, know at the Photian Schism was precipitated by the refusal of Pope Nicholas I to recognize the appointment of Photios, who had been a lay scholar, to the patriarchate of Constantinople by Emperor Michael III. Other factors in the break included jurisdictional rights in the Bulgarian church and the filioque clause. The schism lasted for 13 years from 866-879 with Photios later being recognized as a saint in Easter Orthodoxy but not in Catholicism.

Catalysts

Beside the above-mentioned temporary schisms and general tendencies, there were many specific issues which caused tension between East and West. Some of these were:

- The Filioque‚ÄĒTraditionally, the Nicene Creed spoke of the Holy Spirit "proceeding" from the Father only, but the Western Church began using the filioque clause‚ÄĒ"and the Son"‚ÄĒan innovation rejected by the East and later declared by the Orthodox Church to be a heresy.

- Iconoclasm‚ÄĒThe Eastern Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (in the eighth century), responding in part to the challenge of Islam in his domain, outlawed the veneration of icons. While many Orthodox bishops in the Byzantine Empire rejected this policy, some Eastern bishops cooperated with it, believing the emperor to be God's agent on earth. The Popes‚ÄĒthat is, the bishops of Rome during this period‚ÄĒspoke out strongly both against the policy itself and against the emperor's authority over the church, a tradition which came to be known in the West as Caesaropapism.

- Jurisdiction‚ÄĒDisputes in the Balkans, Southern Italy, and Sicily over whether the Western or Eastern Church had jurisdiction.

- Ecumenical Patriarch‚ÄĒThe designation of the Patriarch of Constantinople as Ecumenical Patriarch, which was understood by Rome as universal patriarch and therefore disputed.

- Primus Inter Pares‚ÄĒDisputes over whether the Patriarch of Rome, the Pope, should be considered a higher authority than the other Patriarchs, or whether he should be considered merely primus inter pares, "the first among equals."

- Caesaropapism‚ÄĒThe Eastern policy of tying together the ultimate political and religious authorities‚ÄĒcharacterized in the West by the term Caesaropapism‚ÄĒwas much stronger in the capital of Constantinople than in Rome, which eventually ceased to be subject to the emperor's power.

- Weakening of other Patriarchates‚ÄĒFollowing the rise of Islam as a political force, the relative weakening of the influence of the Patriarchs of Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria, resulting in Rome and Constantinople emerging as the two real power centers of Christendom, with often competing interests.

- Liturgical practices‚ÄĒThe East objected to Western changes in the liturgy, which it saw as innovations, such the use of unleavened bread for the Eucharist and the popularity of the Western Athanasian Creed, with its use of the filioque.

- Clerical celibacy‚ÄĒThe practice of celibacy began to be required for all clergy in the West, as opposed to the Eastern discipline whereby parish priests could be married if their marriage had taken place when they were still laymen.

Excommunications and final break

When the Norman Christians began using Latin customs with papal approval, Ecumenical Patriarch Michael I Cerularius reacted by ordering the Latin churches of Constantinople to adopt Eastern usages. Some refused, and he reportedly shut them down. He then reportedly caused a letter to be written, though not in his own name, attacking the "Judaistic" practices of the West. The letter was translated and brought to Pope Leo IX, who ordered that a reply be made to each charge, including a defense of papal supremacy.

Cerularius attempted to cool the debate and prevent the impending breach. However the Pope made no concessions. A papal delegation set out in early spring and arrived at Constantinople in April 1054. Their welcome was not to their liking, however, and they stormed out of the palace, leaving the papal response with Ecumenical Patriarch Cerularius, whose anger exceeded even theirs. Moreover, the seals on the letter had been tampered with and the legates had published a draft of the letter for the entire populace to read. The Patriarch then refused to recognize the delegations authority and virtually ignored their mission.[1]

Pope Leo died on April 19, 1054, and the Patriarch's refusal to deal with the delegation provoked them to extreme measures. On July 16, the three legates entered the Church of the Hagia Sophia during the Divine Liturgy and placed a papal bull of excommunication on the altar. The legates fled for Rome two days later, leaving behind a city near riots. The Emperor, who had supported the legates, found himself in an untenable position. The bull was burned, and the legates were anathematized. The Great Schism began.

Despite a state of schism, relations between East and West were not entirely unfriendly. Indeed, the majority of Christians were probably unaware of the above events. The two Churches slid into and out of outright schism over a period of several centuries, punctuated with temporary reconciliations. During the Fourth Crusade, however, Latin crusaders on their way eastward in 1204 sacked Constantinople itself and defiled the Hagia Sophia. The ensuing period of chaotic rule over the looted lands of the Byzantine Empire did nearly irreparable harm to relations between East and West. After that, the break became permanent. Later attempts at reconciliation, such as the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, met with little or no success.

Attempts at Reconciliation

During the twelfth century, the Maronite Church in Lebanon and Syria affirmed its affiliation with the Church of Rome, while preserving most of its own Syriac liturgy. Between then and the twentieth century, some Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Churches entered into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church, thereby establishing the Eastern Catholic Churches as in full communion with the Holy See, while still liturgically and hierarchically distinct from it.

Contemporary Developments

Dialogues in the twentieth century led to the Catholic-Orthodox Joint Declaration of 1965 being adopted on December 7, 1965 at a public meeting of the Second Vatican Council in Rome and simultaneously at a special ceremony in Constantinople. It withdrew the mutual of excommunications of 1054 but stopped short of resolving the Schism. Rather, it expressed a desire for greater reconciliation between the two Churches, represented at the time by Pope Paul VI and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I.

Pope John Paul II visited Romania in May, 1999, invited by Teoctist, the Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church. It was the first visit of a Pope to an Eastern Orthodox country since the Great Schism. After the mass officiated in Izvor Park, Bucharest, the crowd (both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox) chanted "Unity!" Greek monks of certain monasteries at Mount Athos objected to this inter-communion, however, and refused to admit Romanian priests and hieromonks as co-officiants at their liturgies for several years afterwards. Patriarch Teoctist visited Vatican City at the invitation of Pope John Paul II from October 7‚Äď14, 2002.

On November 27, 2004, Pope John Paul II returned the relics of two sainted Archbishops of Constantinople, John Chrysostom and Gregory of Nazianzus, to Constantinople (modern day Istanbul). This step was particularly significant in light of the Orthodox belief that the relics were stolen from Constantinople in 1204 by participants in the Fourth Crusade.

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, together with patriarchs and archbishops of several other Eastern Orthodox Churches, were present at the funeral of Pope John Paul II on April 8, 2005. Bartholomew sat in the first chair of honor. This was the first time for many centuries that an Ecumenical Patriarch attended the funeral of a Pope and was thus considered by many a sign of a serious step toward reconciliation.

On May 29 2005 in Bari, Italy, Pope Benedict XVI cited reconciliation as a commitment of his papacy, saying, "I want to repeat my willingness to assume as a fundamental commitment working to reconstitute the full and visible unity of all the followers of Christ, with all my energy."[2] At the invitation of Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, Pope Benedict later visited Istanbul in November 2006. In December of the same year, Archbishop Christodoulos, head of the Greek Orthodox Church, visited Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican. It was the first official visit by a head of the Church of Greece to the Vatican.

Are the leaders of the two Churches truly serious about solving the problem of the Great Schism? The question can be answered in the affirmative by looking at some of the striking phrases Metropolitan John of Pergamon, as representative of Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, used in his speech at a private audience with Pope John Paul II on June 28, 1998 after the Pope celebrated an ecumenical Mass for the feast of Saints Peter and Paul in Rome: "the bond of love which unites our two churches"; "the full unity which our Lord demands from us"; "restoring our full communion so that the approaching third millennium of the Christian era may find the Church of God visibly united as she was before the great Schism"; and "As Your Holiness has aptly put it some years ago, East and West are the two lungs by which the Church breathes; their unity is essential to the healthy life of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church."[3] Also, in order to solve the divisive theological issue on filioque, a common ground has been sought jointly between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism especially after the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity prepared a document in September 1995 entitled "The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit," with its emphasis on the Father as the source of the whole Trinity.[4]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ John Julius Norwich. The Normans in the South 1016-1130 (Longmans, Green and Co., Ltd., 1967), 102.

- ‚ÜĎ "Pope Benedict's 1st Papal Trip," CBS News. May 29, 2005.

- ‚ÜĎ "Speeches of Pope John Paul II and Metropolitan John of Pergamon." Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ "The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit." Retrieved May 7, 2008.

See also

- Filioque clause

- Photios

- Western Christianity

- Eastern Christianity

- Fourth Crusade

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chadwick, Henry. East and West The Making of a Rift in the Church: from Apostolic Times Until the Council of Florence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780199264575

- K√ľng, Hans, and J√ľrgen Moltmann. Conflicts About the Holy Spirit. New York: Seabury Press, 1979. ISBN 9780816420353

- Norwich, John Julius. The Normans in the South 1016-1130. Longmans, Green and Co., Ltd., 1967. ISBN 9780582107519.

- Posnov, Mikhail, and Thomas E. Herman. The History of the Christian Church Until the Great Schism of 1054. Bloomington, Ind: AuthorHouse, 2004. ISBN 9781418473266

- Runciman, Steven. The Eastern Schism: A Study of the Papacy and the Eastern Churches During the XIth and XIIth Centuries. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955. OCLC 49983763

- Vischer, Lukas. Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ: Ecumenical Reflections on the Filioque Controversy. Faith and order paper, no. 103, World Council of Churches. London: SPCK, 1981. ISBN 9780281038206

- Whelton, Michael. Popes and Patriarchs: An Orthodox Perspective on Roman Catholic Claims. Ben Lomond, Calif: Conciliar Press, 2006. ISBN 1888212780

External links

All links retrieved May 24, 2024.

- Byzantium: The Great Schism By Bp. Kallistos Ware www.fatheralexander.org

- Adrian Fortescue Catholic Encyclopedia article, 1911 ed. representing a Roman Catholic view. www.newadvent.org

- In Our Time page with link to online talk www.bbc.co.uk

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.