Difference between revisions of "Prostitution" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

In 1934, an Austrian philosopher named Hans Kelsen continued the positivist tradition in his book the ''[[Pure Theory of Law]]''.<ref>{{cite book |last=Kelsen |first=Hans |authorlink=Hans Kelsen |title=[[Pure Theory of Law]] |year=1934 }}</ref> Kelsen believed that though law is separate from morality, it is endowed with "normativity", meaning we ought to obey it. Whilst laws are positive "is" statements (e.g. the fine for reversing on a highway ''is'' $500), law tells us what we "should" do (i.e. not drive backwards). So every legal system can be hypothesised to have a basic norm (''[[Grundnorm]]'') telling us we should obey the law. | In 1934, an Austrian philosopher named Hans Kelsen continued the positivist tradition in his book the ''[[Pure Theory of Law]]''.<ref>{{cite book |last=Kelsen |first=Hans |authorlink=Hans Kelsen |title=[[Pure Theory of Law]] |year=1934 }}</ref> Kelsen believed that though law is separate from morality, it is endowed with "normativity", meaning we ought to obey it. Whilst laws are positive "is" statements (e.g. the fine for reversing on a highway ''is'' $500), law tells us what we "should" do (i.e. not drive backwards). So every legal system can be hypothesised to have a basic norm (''[[Grundnorm]]'') telling us we should obey the law. | ||

| − | |||

Later in the twentieth century [[H.L.A. Hart]] attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in ''[[The Concept of Law]]''<ref name="hhc"/>. As the chair of jurisprudence at [[Oxford University]], Hart argued law is a "system of rules". Rules, said Hart, are divided into primary rules (rules of conduct) and secondary rules (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students have continued the debate since. [[Ronald Dworkin]] was his successor in the Chair of Jurisprudence at Oxford and his greatest critic. In his book ''Law's Empire''<ref name="rdl"/> Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an "[[interpretivism|interpretive]] concept", that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions. [[Joseph Raz]] on the other hand has defended the positivist outlook and even criticised Hart's 'soft social thesis' approach in ''The Authority of Law''<ref name="jra"/>. Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social sources, without reference to moral reasoning. Any categorisation of rules beyond their role as authoritative dispute mediation is best left to sociology, rather than jurisprudence.<ref>ch. 2, Joseph Raz, ''The Authority of Law'' (1979) Oxford University Press</ref> | Later in the twentieth century [[H.L.A. Hart]] attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in ''[[The Concept of Law]]''<ref name="hhc"/>. As the chair of jurisprudence at [[Oxford University]], Hart argued law is a "system of rules". Rules, said Hart, are divided into primary rules (rules of conduct) and secondary rules (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students have continued the debate since. [[Ronald Dworkin]] was his successor in the Chair of Jurisprudence at Oxford and his greatest critic. In his book ''Law's Empire''<ref name="rdl"/> Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an "[[interpretivism|interpretive]] concept", that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions. [[Joseph Raz]] on the other hand has defended the positivist outlook and even criticised Hart's 'soft social thesis' approach in ''The Authority of Law''<ref name="jra"/>. Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social sources, without reference to moral reasoning. Any categorisation of rules beyond their role as authoritative dispute mediation is best left to sociology, rather than jurisprudence.<ref>ch. 2, Joseph Raz, ''The Authority of Law'' (1979) Oxford University Press</ref> | ||

{{seealso|Political philosophy}} | {{seealso|Political philosophy}} | ||

| Line 167: | Line 166: | ||

===Economic analysis of law=== | ===Economic analysis of law=== | ||

{{Main|Economic analysis of law}} | {{Main|Economic analysis of law}} | ||

| − | |||

Economic analysis of law is an approach to legal theory that incorporates and applies the methods and ideas of [[economics]] to law. The discipline arose partly out of a critique of trade unions and U.S. [[Antitrust]] law. Today's proponents, such as [[Richard Posner]] from the so called [[Chicago School (economics)|Chicago School]] of economists and lawyers, are generally advocates of deregulation, privatization, and are hostile to state regulation, or what they see as restrictions on the operation of [[free market]]s. | Economic analysis of law is an approach to legal theory that incorporates and applies the methods and ideas of [[economics]] to law. The discipline arose partly out of a critique of trade unions and U.S. [[Antitrust]] law. Today's proponents, such as [[Richard Posner]] from the so called [[Chicago School (economics)|Chicago School]] of economists and lawyers, are generally advocates of deregulation, privatization, and are hostile to state regulation, or what they see as restrictions on the operation of [[free market]]s. | ||

| Line 185: | Line 183: | ||

[[Image:Palace-of-westminster-at-dawn.JPG|thumb|left|The [[Palace of Westminster|British Houses of Parliament]]]] | [[Image:Palace-of-westminster-at-dawn.JPG|thumb|left|The [[Palace of Westminster|British Houses of Parliament]]]] | ||

The [[Palace of Westminster]] in London, the [[United States Congress|Congress]] in Washington D.C., the [[Bundestag]] in Berlin, the [[Duma]] in Moscow, and so on, are examples of legislatures. The principle of representative government means that people vote for political decision makers to carry out their wishes. Most Parliaments are bi-cameral, so that in a 'lower house' the politicians may return from elected constituencies, and in the 'upper house' they may be elected through [[proportional representation]] (as in Australia), Crown appointment (as in the UK), or state elections (as in the U.S.). Parliaments are the legislative authorities in most countries. To enact legislation a majority of Members of Parliament must vote for a bill, unless a country has an entrenched constitution, requiring some special majority for constitutional amendments. A government usually leads the process, formed either from Members of Parliament (as in the U.K. or Germany), or elected to executive office separately and appointing a cabinet that is unelected (as in the U.S.). | The [[Palace of Westminster]] in London, the [[United States Congress|Congress]] in Washington D.C., the [[Bundestag]] in Berlin, the [[Duma]] in Moscow, and so on, are examples of legislatures. The principle of representative government means that people vote for political decision makers to carry out their wishes. Most Parliaments are bi-cameral, so that in a 'lower house' the politicians may return from elected constituencies, and in the 'upper house' they may be elected through [[proportional representation]] (as in Australia), Crown appointment (as in the UK), or state elections (as in the U.S.). Parliaments are the legislative authorities in most countries. To enact legislation a majority of Members of Parliament must vote for a bill, unless a country has an entrenched constitution, requiring some special majority for constitutional amendments. A government usually leads the process, formed either from Members of Parliament (as in the U.K. or Germany), or elected to executive office separately and appointing a cabinet that is unelected (as in the U.S.). | ||

| + | |||

===Executive=== | ===Executive=== | ||

{{Main|Executive (government)|Head of State}} | {{Main|Executive (government)|Head of State}} | ||

| − | |||

In most democratic countries, like the UK, Germany, India and Japan, the executive is elected into and drawn from the legislature and is known as a [[cabinet]]. Alongside there is usually a hereditary, or an appointed head of state, such as the [[Queen of the United Kingdom]], or the [[President of Germany|Bundespräsident]] which carries out the symbolic function of enacting legislation, but has no formal political power. The other important model is found in countries like France, the U.S. and Russia. Here the executive, is directly elected by a popular vote, and may appoint a cabinet that is not directly elected. | In most democratic countries, like the UK, Germany, India and Japan, the executive is elected into and drawn from the legislature and is known as a [[cabinet]]. Alongside there is usually a hereditary, or an appointed head of state, such as the [[Queen of the United Kingdom]], or the [[President of Germany|Bundespräsident]] which carries out the symbolic function of enacting legislation, but has no formal political power. The other important model is found in countries like France, the U.S. and Russia. Here the executive, is directly elected by a popular vote, and may appoint a cabinet that is not directly elected. | ||

| Line 201: | Line 199: | ||

===Bureaucracy=== | ===Bureaucracy=== | ||

{{Main|Bureaucracy}} | {{Main|Bureaucracy}} | ||

| − | |||

The word "bureaucracy" derives from the French for "office" (''bureau'') and Ancient Greek for "power" (''kratos''). It refers to all government servants and bodies who carry out the wishes of the executive. The concept dates from 18th century France. [[Friedrich Melchior, baron von Grimm|Baron de Grimm]], a German author who lived in France, wrote in 1765, | The word "bureaucracy" derives from the French for "office" (''bureau'') and Ancient Greek for "power" (''kratos''). It refers to all government servants and bodies who carry out the wishes of the executive. The concept dates from 18th century France. [[Friedrich Melchior, baron von Grimm|Baron de Grimm]], a German author who lived in France, wrote in 1765, | ||

Revision as of 00:04, 25 January 2007

- For other senses of this word, see Law (disambiguation).

Law has been defined as a "system of rules"[1], as an "interpretive concept"[2] to achieve justice, as an "authority"[3] to mediate people's interests, and even as "the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction"[4]. The numerous ways law might be thought of reflects the numerous ways law comes into everyone's lives. Contract law governs everything from buying a bus ticket, to obligations in the workplace. When buying or renting a house, property law defines people's rights and duties towards the bank, or landlord. When earning pensions, trust law protects savings. Tort law allows claims for compensation when someone or their property is harmed. But if the harm is criminalised, and the act is intentional, then criminal law ensures that the perpetrator is removed from society. Society itself is built upon law. Constitutional law provides a framework for making new laws, protecting people's human rights and electing political representatives. Administrative law allows ordinary citizens to challenge the way government bodies exercise their power. Between different societies, international law builds bridges, so that people everywhere can lead better lives. "The rule of law," wrote the philosopher Aristotle in 350B.C.E., "is better than the rule of any individual."[5]

The study of law raises important questions about equality, fairness and justice. This is not always simple. "In its majestic equality," wrote the author Anatole France in 1894, "the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread."[6] Every legal system elaborates legal rights and responsibilities in different ways. Most countries have a codified system of civil law which is regularly updated by governments. Many others use common law which develops through judicial precedent. Small numbers of countries still base their law on religious texts. But in all places there is a rich history to law, with deep philosophical ideas underpinning it. Law raises pressing economic issues, just as intense political battles are fought to mould law throughout its institutions. Professionals are usually trained to give people advice about their legal rights and duties and represent them in court. But despite the complexity, law is a highly rewarding study. The word law derives from the late Old English lagu, meaning something laid down or fixed. [7]

Legal subjects

All legal systems deal with similar issues that recur throughout society, although different categories and names may be given. Moreover, there are certain core subjects, that students are required to learn in order to practise law. For example, in England these are criminal law, contract, tort, property law, equity and trusts, constitutional and administrative law and European Community Law. Sometimes people distinguish "public law", which relates closely to the state (including constitutional, administrative and criminal law), from "private law", which can include contract, tort, property and many further disciplines. In civil law systems contract and tort would fall under a general law of obligations and trusts law is dealt with under statutory regimes or international conventions. Outside Europe, students may focus on different regional agreements, such as NAFTA, SAFTA, CSN, ASEAN or the African Union. But it is the unity and the things that all legal systems have in common, not the differences, that is the most remarkable feature of law in today's world.

International law

In a global economy, law is globalising too. International law can refer to three things, public international law, private international law or conflict of laws and the law of supranational organisations.

- Public international law concerns the relationships between sovereign nations. The United Nations, founded under the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is the most important international organisation. It was established after the failure of the Versailles Treaty and World War II. Other international agreements, like the Geneva Conventions on the conduct of war and international bodies such as the International Labour Organisation, the World Trade Organisation, or the International Monetary Fund also form a growing part of public international law.

- Conflict of Laws (or "private international law" in civil law countries) concerns which jurisdiction a legal dispute between private parties should be heard in and which jurisdiction's law should be applied. Today businesses are increasingly capable of shifting capital and labour supply chains across borders, as well as trading with overseas businesses. This increases the number of disputes outside a unified legal framework and the enforceability of standard practices. Increasing numbers of businesses opt for commercial arbitration under the New York Convention 1958.

- European Union law is the first and only example of a supranational legal framework. However, given increasing global economic integration, many regional agreements, especially the South American Community of Nations, are on track to follow the same model. In the EU, sovereign nations have pooled their authority through a system of courts and political institutions. It constitutes "a new legal order of international law"[8] for the mutual social and economic benefit of the member states.

Constitutional and administrative law

Constitutional and administrative law govern the affairs of the state. Constitutional law governs the relationships between the executive, legislature and judiciary. Human rights or civil liberties also form part of a country's constitution and govern the rights of the individual against the state. Most jurisdictions, like the United States and France, have a single codified constitution, with a Bill of Rights. A few, like the United Kingdom, have no such document; in those jurisdictions the constitution is composed of statute, case law and convention. A case named Entick v. Carrington[9] illustrates a constitutional principle deriving from the common law. Mr Entick's house was searched and ransacked by Sherrif Carrington. Carrington argued that a warrant from a Government minister, the Earl of Halifax was valid authority, even though there was no statutory provision or court order for it. The court, led by Lord Camden stated that,

"The great end, for which men entered into society, was to secure their property. That right is preserved sacred and incommunicable in all instances, where it has not been taken away or abridged by some public law for the good of the whole... If no excuse can be found or produced, the silence of the books is an authority against the defendant, and the plaintiff must have judgment."

Inspired by John Locke,[10] the fundamental constitutional principle is that the individual can do anything but that which is forbidden by law, while the state may do nothing but that which is authorised by law. Administrative law is the chief method for people to hold state bodies to account. People can apply for judicial review of actions or decisions by local councils, public services or government ministries, to ensure that they comply with the law. The first specialist administrative court was the Conseil d'Etat set up in 1799, as Napoleon assumed power in France.

Criminal law

Criminal law is the most familiar kind of law from the papers, or news on TV, despite its relatively small part in the legal whole. In every jurisdiction, a crime is committed where two elements are fulfilled. First, the criminal must have the requisite malicious intent to do a criminal act, or mens rea (guilty mind). Second, he must commit the criminal act, or actus reus (guilty act). Examples of different kinds of crime might include murder, assault, fraud or theft. Defences can exist to some crimes, such as killing in self defence, or pleading insanity. A famous case in 19th century England, R v. Dudley and Stephens [11] involved the defence of "necessity". The Mignotte, sailing from Southampton to Sydney, sank. Three crew members, and a cabin boy, were stranded on a raft. They were starving, the cabin boy close to death. So the crew killed and ate the cabin boy. The crew survived and were rescued, but put on trial for murder. They argued it was necessary to kill the cabin boy to preserve their own lives. Lord Coleridge, expressing immense disapproval, ruled, "to preserve one's life is generally speaking a duty, but it may be the plainest and the highest duty to sacrifice it." They were sentenced to hang. Yet public opinion, especially among sea farers was outraged and overwhelmingly supportive. In the end, the Crown commuted their sentences to six months.

Criminal matters are considered to be offences against the whole community, rather than the individual victims. Hence the government takes the lead in prosecution, cases are cited as "The People v. ..." or "R. v. ..." and in many countries, lay juries determine the guilt of defendants on points of fact (but not the law itself). In some areas, criminal law is moving towards strict liability, so that malicious intent need not be proven. In the case of environmental harm, or corporate manslaughter by big business, strict liability can mean company directors can still be criminally responsible for orders carried out by staff. Some developed countries still have capital punishment and torture for criminal activity, but the normal punishment for a crime will be imprisonment, fines, or community service. On the international field most countries have signed up to the International Criminal Court, which was set up to try people for crimes against humanity.

Contract

Contract is based on the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (promises must be kept)[12]. Almost everyone makes contracts everyday. Contracts can be made orally (e.g. buying a newspaper in a shop) or in writing (e.g signing a contract of employment). Sometimes formalities, such as writing the contract down or having it witnessed, are required for the contract to take effect (e.g. when buying a house[13]).

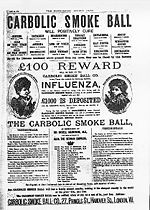

In common law jurisdictions there are three key elements to the creation of a contract. These are offer and acceptance, consideration and an intention to create legal relations. For example, in Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company[14] a medical firm advertised that its new wonder drug, the smokeball, would cure people's flu, and if it did not, buyers would get £100. Lots of people sued for their £100 when it did not work. Fearing bankruptcy, Carbolic argued the advert was not to be taken as a serious, legally binding offer. It was merely an invitation to treat, or mere puff, a gimmick. But the court of appeal held that to a reasonable man Carbolic had made a serious offer. People had given good "consideration" for it by going to the "distinct inconvenience" of using a faulty product. "Read the advertisement how you will, and twist it about as you will," said Lord Justice Lindley, "here is a distinct promise expressed in language which is perfectly unmistakable".

In civil law jurisdictions, consideration is not necessarily a requirement for a contract.[15] "Consideration" means all parties to a contract must exchange something of value to be able to enforce it. In France, for instance, an ordinary contract is said to form simply on the basis of a 'meeting of the minds' or a 'concurrence of wills'. Yet in some common law systems, like Australia, the concept of culpa in contrahendo or estoppel is increasingly used to create obligations during pre-contractual negotiations.[16] Germany has a special approach to contracts, which ties into property law. Their 'abstraction principle' (Abstraktionsprinzip) means that the personal obligation of contract forms separately to the title of property being conferred. When contracts are invalidated for some reason, e.g. a car buyer was so drunk that he lacked legal capacity to contract,[17] the contractual obligation to pay can be invalidated separate from proprietary title of the car. Unjust enrichment law, rather than the law of contract, is then used to restore title to the rightful owner.

Tort

Tort (also "delict") means 'civil wrong'. In order to have behaved tortiously, one must have breached a duty to another person, or infringed some pre-existing legal right. A simple example might be accidentally hitting someone with a cricket ball.[18] In the law of negligence, the injured party has a claim. Another example might be a neighbour making excessively loud noises with machinery on his property.[19] Under a nuisance claim the noise could be stopped. Torts can also involve intentional acts, such as assault, battery or trespass. Of the better known torts are defamation, for example when a newspaper libels a politician[20] or economic torts, which form the basis of labour law in some countries by making trade unions liable for strikes,[21] where statute does not provide immunity[22].

Negligence is the most common form of tort. Its principles are illustrated by Donoghue v. Stevenson[23]. Mrs Donoghue ordered an opaque bottle of ginger beer in a cafe in Paisley. Having consumed half of it, she poured the remainder into a tumbler. The decomposing remains of a dead snail floated out. She fell ill and sued the manufacturer for carelessly allowing the drink to be contaminated. The House of Lords decided that the manufacturer was liable for Mrs Donoghue's illness, because (1) he owed Mrs. Donoghue a duty of care to provide safe drinks, (2) he breached his duty of care, (3) the harm would not have occurred but for his breach, and (4) his act was the proximate cause, or not too remote a consequence, of her harm.

Property law

Property law governs everything that people call 'theirs'. Real property, sometimes called 'real estate' or a right in rem refers to ownership of land and things attached to it.[24] Personal property, or a right in personam refers to everything else; movable objects, like computers or sandwiches or intangible rights, like company shares or a copyright on a song. The classic civil law approach to property, propounded by Friedrich Carl von Savigny is that it is a right good against the world. This contrasts to an obligation, like a contract or tort, which is a right good between individuals.[25] Preferred in common law jurisdictions is an idea closer to an obligation; that the person who can show the best claim to a piece of property, against any contesting party, is the owner.[26] The idea of property raises important philosophical and political issues. John Locke famously argued that our "lives, liberties and estates" are our property because we own our bodies and mix our labour with our surroundings.[27] But property is still a contentious concept. French philosopher Pierre Proudhon most famously proclaimed, "property is theft". [28]

Land law forms the basis for most kinds of property law, and is the most complex. It concerns mortgages, rental agreements, licences, convenants, easements and the statutory systems for registration of land. Regulations on the use of personal property fall under intellectual property, company law, trusts and commercial law.

Trusts and equity

The trust is a form of ownership that developed in England through the courts of Chancery. It is part of a body of law known as 'equity'. Equity used to be administered by the English Lord Chancellor separately from common law courts. It operates on the basis of certain principles that remedied injustice that the common law created. Whereas at law, there may be only one owner of a piece of property, under a trust, the legal ownership of property is split. So called 'trustees' control the property, whereas the 'beneficial' (or 'equitable') ownership of the trust property is held by people known as 'beneficiaries'. Trusts are used mostly for holding large amounts of money. The most familiar kind of trust is a pension fund, where banks are trustees for people's savings until their retirement. Company law is historically based on the trust instrument. But trusts can also be set up for charitable purposes, famous examples being the British Museum or the Rockefeller Foundation.

Trustees owe things called equitable and fiduciary duties to the beneficiaries who they hold trust property for[29]. They must use the trust property for the benefit of the beneficiaries, rather than for themselves[30]. Depending on the particular trust law of the jurisdiction, the nature of the trust property and the terms of the instrument that created the trust, the trustees will usually be expected to invest it or sell it[31], allow the beneficiaries to reside in it, or to transfer it to the beneficiaries absolutely.

Further disciplines

Law spreads far beyond the core subjects, into practically every area of life. Three categories are presented for convenience, though the subjects intertwine and flow into one another. Moreover these subjects may be of even greater practical importance than the traditional core subjects. The best way to grasp their importance is careful individual study.

- Law and Society

- Labour law is the study of a tripartite industrial relationship, between worker, employer and trade union. This involves collective bargaining regulation, and the right to strike. Individual employment law refers to workplace rights, such as health and safety or a minimum wage.

- Human rights is an important field to guarantee everyone basic freedoms and entitlements. These are laid down in codes such as the U.N. Charter, the European convention on human rights and the U.S. Bill of Rights.

- Civil procedure and criminal procedure concern the rules that courts must follow as a trial and appeals proceed. Both concern everybody's right to a fair trial or hearing.

- Evidence law involves which materials are admissible in courts for a case to be built.

- Immigration law and nationality law concern the rights of foreigners to live and work in a nation state that is not their own and to acquire or lose citizenship. Both also involve the rights of asylum and the problem of stateless individuals.

- Social security law refers to the rights people have to social insurance, such as jobseekers allowances or housing benefits.

- Family law covers marriage and divorce proceedings, the rights of children and of course the rights to property and money in the event of separation.

- Law and Commerce

- Commercial law is essentially complicated contract law. It deals with the Sale of Goods Acts and codified common law of commercial principles.

- Company law sprung from the law of trusts, on the principle of separating ownership and control.[32] The law of the modern company began with the Joint Stock Companies Act, passed in the United Kingdom in 1865, which protected investors with limited liability and conferred separate legal personality.

- Intellectual property deals with patents, trademarks and copyrights. These are intangible assets, like the right not to have your idea for an invention stolen, a brand name or a song you have written.

- Restitution deals with the recovery of someone else's gain, rather than compensation for one's own loss.

- Unjust enrichment is law covering a right to retrieve property from someone that has profited unjustly at another's expense.

- Law and Regulation

- Tax law is probably the most complicated and well paid discipline, involving Value Added Tax, Corporation Tax, Income Tax, and most importantly, lots of money.

- Banking law and financial regulation set minimum standards on the amounts of capital banks must hold, and rules about best practice for investment. This is to insure against the risk of economic crises, such as the Wall Street Crash.

- Regulated industries are attached to an important body of law for the provision of public services. Since privatization became popular, private companies doing the jobs previously controlled by government have been bound by social responsibilities. Utilities, Telecomms and Water are regulated industries in most OECD countries.

- Competition law, in the U.S. known as antitrust law, is an evolving and relatively new kind of law that began in the late 19th Century with the restraint of trade doctrine. The U.S. adopted anti-cartel and anti-monopoly statutes around the turn of that century. See the Sherman Act and Clayton Act.

- Consumer Law could include anything from regulations on unfair contract terms and conditions, or directives on airline baggage insurance.

- Environmental law is increasingly important, especially in light of the Kyoto Protocol and the imminent danger of climate change. Environmental protection also serves to penalise polluters within countries.

Legal systems

In general, legal systems around the world can be split between civil law (legal system) jurisdictions on the one hand and on the other systems using common law and equity. This is largely the result of countries having a shared history. The term civil law, referring to a legal system, should not be confused with civil law as distinguished from criminal law, or as distinguished from public law. A third type legal system still accepted by some countries, even whole countries, is religious law, based on Biblical transcripts.

Civil law

Civil law, as a type of legal system, is the form of law used by most countries around the world today. Civil law systems mainly derive from the Roman Empire, and more particularly, the Corpus Juris Civilis issued by the Emperor Justinian ca. 529C.E. This was an extensive reform of the law in the Eastern Empire, bringing it together into codified documents. Civil law today, in theory, is interpreted rather than developed or made by judges. Only legislative enactments (rather than judicial precedents) are considered legally binding. However, in reality courts do pay attention to previous decisions, especially from higher courts. Countries that have civil law systems include France, Germany, Russia, Japan, China and most of central and Latin America.

Common law and equity

English Law is the father of common law and equity, and is used in Commonwealth countries or former countries from the British Empire, with the exception of Malta and Scotland both of which have an ingrained Civil Law system. The doctrine of stare decisis or precedent by courts is the major innovation and difference to codified civil law systems. Common law is currently in practice in Ireland, United Kingdom, Australia, India, South Africa, Canada (excluding Quebec), and the United States (excluding Louisiana) and many more places. In addition to these countries, several others have adapted the common law system into a mixed system. For example, Pakistan, India and Nigeria operate largely on a common law system, but incorporate religious law. In the European Union the Court of Justice takes an approach mixing civil law (based on the treaties) with an attachment to the importance of case law. One of the most fundamental documents to shape common law is the Magna Carta[33] which placed limits on the power of the English Kings. It served as a kind of mediaeval bill of rights for the aristocracy and the judiciary who developed the law.

Religious law

The main kinds of religious law are Halakha in Judaism, Sharia in Islam, and Canon law in some Christian groups. In some cases these are intended purely as individual moral guidance, whereas in other cases they are intended and may be used as the basis for a country's legal system. The Halakha is followed by orthodox and conservative Jews in both ecclesiastical and civil relations. No country is fully governed by Halakha, but two Jewish people may decide, because of personal belief, to have a dispute heard by a Jewish court, and be bound by its rulings. Sharia Law governs a number of Islamic countries, including Saudi Arabia and Iran, though most countries use Sharia Law only as a supplement to national law. It can relate to all aspects of civil law, including property rights, contracts or public law. Canon law survives in use by the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Communion.

Jurisdictions

Despite the usefulness of different classifications, every legal system has its own individual identity. Below are groups of legal systems, categorised by their geography. Click the "show" buttons on the right for the lists of countries.

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Law of South America | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states | Argentina · Bolivia · Brazil · Chile · Colombia · Ecuador · Guyana · Panama* · Paraguay · Peru · Suriname · Trinidad and Tobago* · Uruguay · Venezuela |

| Dependencies | Aruba* (Netherlands) · Falkland Islands (UK) · French Guiana (France) · Netherlands Antilles* (Netherlands) · South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (UK) |

| ||||||||

Template:Europe in topic Template:Oceania in topic

Legal theory

History of law

The history of law is, in a broad sense, the history of human civilization. Almost every legal system is interconnected in some way, each body of law being influenced by outside forces and jurisdictions over time.

- Ancient law

- Ancient Egyptian law had a civil code, based on the concept of Ma'at. Tradition, rhetorical speech, social equality and impartiality were key principles.[34] Judges kept records, which were used as precedent, although the systems developed slowly.

- In ancient Babylon, the King Hammurabi made the innovation of publishing his code of laws for the public to see in the market. This became known as the Codex Hammurabi, part of a vast and complex body of babylonian law

- The Noahide Laws listed in the Torah were moral imperatives for forming a foundation for a well-functioning unified society. They were eventually succeeded by the Torah, Mishna, Talmud and Responsa.

- In Ancient Athens, the small Greek city-state developed the first government based on broad inclusion of the citizenry, excluding women and the slave class. Ancient greek law contained major constitutional innovations in the development of democracy.

- European law

Roman law underwent major codification in the Corpus Juris Civilis of Emperor Justinian, as later developed through the Middle Ages by mediæval legal scholars. In Mediaeval England, judges retained greater power than their continental counterparts and began to develop a body of precedent. Originally civil law was one common legal system in much of Europe, but with the rise of nationalism in the 17th century Nordic countries and around the time of the French Revolution, it became fractured into separate national systems. This change was brought about by the development of separate national codes, of which the French Napoleonic Code and the German and Swiss codes were the most influential. Around this time civil law incorporated many ideas associated with the Enlightenment. The European Union's Law is based on a codified set of laws, laid down in the Treaties. Law in the EU is however mixed with precedent in case law of the European Court of Justice.

- Asian law

Ancient China and ancient India had historically independent schools of legal theory and practice such as the Laws of Manu or the Arthashastra in India and traditional Chinese law in China. Because Germany was a rising power in the late 19th century, and because civil law codifications are more 'exportable' the large bodies of common law jurisprudence, the German Civil Code has been highly influential for most oriental legal systems, and forms the basis of civil law in Japan and South Korea. In China, the German Civil Code was introduced in the later years of the Qing Dynasty and formed the basis of the law of the Republic of China which remains in force in Taiwan. The current legal infrastructure in the People's Republic of China reflects influences from the German-based civil law, English-based common law in Hong Kong, Soviet-influenced Socialist law, United States-style banking and securities law, and traditional Chinese law. In India, and other previous members of the Commonwealth, English common law forms the basis of private law.

Philosophy of law

The philosophy of law is known as jurisprudence. Normative jurisprudence is essentially political philosophy and asks "what should law be?". Analytic jurisprudence asks on the other hand, "what is law?". An early famous philosopher of law was John Austin, a student of Jeremy Bentham and first chair of law at the new University of London from 1829. Austin's utilitarian answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".[4] This approach was long accepted, especially as an alternative to natural law theory. Natural lawyers argue human law reflects essentially moral and unchangeable laws of nature. For instance, Immanuel Kant believed a moral imperative requires laws "be chosen as though they should hold as universal laws of nature".[35] Austin and Bentham, following David Hume thought this conflated what "is" and what "ought to be" the case. They believed in law's positivism, that real law is entirely separate from "morality".

In 1934, an Austrian philosopher named Hans Kelsen continued the positivist tradition in his book the Pure Theory of Law.[36] Kelsen believed that though law is separate from morality, it is endowed with "normativity", meaning we ought to obey it. Whilst laws are positive "is" statements (e.g. the fine for reversing on a highway is $500), law tells us what we "should" do (i.e. not drive backwards). So every legal system can be hypothesised to have a basic norm (Grundnorm) telling us we should obey the law.

Later in the twentieth century H.L.A. Hart attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in The Concept of Law[1]. As the chair of jurisprudence at Oxford University, Hart argued law is a "system of rules". Rules, said Hart, are divided into primary rules (rules of conduct) and secondary rules (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students have continued the debate since. Ronald Dworkin was his successor in the Chair of Jurisprudence at Oxford and his greatest critic. In his book Law's Empire[2] Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an "interpretive concept", that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions. Joseph Raz on the other hand has defended the positivist outlook and even criticised Hart's 'soft social thesis' approach in The Authority of Law[3]. Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social sources, without reference to moral reasoning. Any categorisation of rules beyond their role as authoritative dispute mediation is best left to sociology, rather than jurisprudence.[37]

- See also: Political philosophy

Economic analysis of law

Economic analysis of law is an approach to legal theory that incorporates and applies the methods and ideas of economics to law. The discipline arose partly out of a critique of trade unions and U.S. Antitrust law. Today's proponents, such as Richard Posner from the so called Chicago School of economists and lawyers, are generally advocates of deregulation, privatization, and are hostile to state regulation, or what they see as restrictions on the operation of free markets.

The most decorated economic analyst of law is 1991 Nobel Prize winner Ronald Coase. His first major article, The Nature of the Firm (1937),[38] argued that the reason for the existence of firms (companies, partnerships, etc) is the existence of transaction costs. Rational individuals trade through bilateral contracts on open markets until the costs of transactions mean that using corporations to produce things is more cost effective. His second major article, The Problem of Social Cost (1960)[39] argued that if we lived in a world without transaction costs, people would bargain with one another to create the same allocation of resources, regardless of the way a court might rule in property disputes. Coase used the example of a nuisance case named Sturges v. Bridgman,[40] where a noisy sweetmaker and a quiet doctor were neighbours and went to court to see who should have to move. Coase said that regardless of whether the judge ruled that the sweetmaker had to stop using his machinery, or that the doctor had to put up with it, they could strike a mutually beneficial bargain about who moves house that reaches the same outcome of resource distribution. Only, the existence of transaction costs may prevent this. So the law ought to pre-empt what would happen, and be guided by the most efficient solution. The idea is that law, and regulation, is not as important or effective at helping people as lawyers, and government planners, believe.

Legal institutions

The main institutions of law in industrialised countries are independent courts, representative parliaments, an accountable executive, the military and police, bureaucratic organisation, the profession of lawyers and civil society itself. John Locke in Two Treatises On Civil Government [41] and Baron de Montesquieu after him in Spirit of Laws [42] advocated a separation of powers between the institutions that wield political influence, namely the judiciary, legislature and executive. Their principle was that no person should be able to usurp, as Thomas Hobbes wanted for an all powerful sovereign, a Leviathan of power. Karl Marx and Max Weber have been pivotal in shaping thinking in the twentieth century about the extensions of the state, which come under the control of the executive. Military, policing and bureaucratic power over ordinary citizens' daily lives pose special problems for accountability that earlier writers like Locke and Montesquieu could not have foreseen. The custom and practice of the legal profession itself is an important part of people's access to justice, whilst civil society is a term used to refer the social institutions, communities and partnerships that are the political base of the law.

Judiciary

Most countries have a system of appeals courts, up to a supreme authority. In the U.S. this would be the Supreme Court[43], in Australia the High Court. In the U.K. the highest court is the House of Lords[44], but on questions of European Community Law or Human Rights Law, the European Court of Justice[45] in Luxembourg and the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg are the E.U. authorities. Also in the E.U. is the German Bundesverfassungsgericht[46] and the French Cour de Cassation. Some courts are bound by constitutions and may interpret them, whilst the UK continues to assert the ideal of parliamentary sovereignty, whereby the elected legislature holds power.

Legislature

The Palace of Westminster in London, the Congress in Washington D.C., the Bundestag in Berlin, the Duma in Moscow, and so on, are examples of legislatures. The principle of representative government means that people vote for political decision makers to carry out their wishes. Most Parliaments are bi-cameral, so that in a 'lower house' the politicians may return from elected constituencies, and in the 'upper house' they may be elected through proportional representation (as in Australia), Crown appointment (as in the UK), or state elections (as in the U.S.). Parliaments are the legislative authorities in most countries. To enact legislation a majority of Members of Parliament must vote for a bill, unless a country has an entrenched constitution, requiring some special majority for constitutional amendments. A government usually leads the process, formed either from Members of Parliament (as in the U.K. or Germany), or elected to executive office separately and appointing a cabinet that is unelected (as in the U.S.).

Executive

In most democratic countries, like the UK, Germany, India and Japan, the executive is elected into and drawn from the legislature and is known as a cabinet. Alongside there is usually a hereditary, or an appointed head of state, such as the Queen of the United Kingdom, or the Bundespräsident which carries out the symbolic function of enacting legislation, but has no formal political power. The other important model is found in countries like France, the U.S. and Russia. Here the executive, is directly elected by a popular vote, and may appoint a cabinet that is not directly elected.

Military and police

The military and police are sometimes referred to as "the long arms of the law". Whilst military organisation has existed as long as have governments, a standing police force is a relatively modern invention. Mediaeval England, for instance, used a system of travelling criminal courts, or assizes to keep communities under control. The first modern police were probably those in 17th century Paris, in the court of Louis XIV, although the Paris Prefecture of Police's website claims were the first uniformed policemen in the world[47]. In 1829, after the French Revolution and Napoleon's dictatorship, a government decree created the first uniformed policemen in Paris and all French cities, known as sergents de ville ("city sergeants"). In Britain, the Metropolitan Police Act 1829 was passed by Parliament under home secretary Sir Robert Peel, founding the London Metropolitan Police.

Sociologist Max Weber famously argued that the state is that which controls the legitimate monopoly of the means of violence.[48] Military and police personnel carry out enforcement activities at the request of the government or the courts. The term failed state is used where the police and military no longer uphold security and order and society descends into civil war, anarchy or chaos.

Bureaucracy

The word "bureaucracy" derives from the French for "office" (bureau) and Ancient Greek for "power" (kratos). It refers to all government servants and bodies who carry out the wishes of the executive. The concept dates from 18th century France. Baron de Grimm, a German author who lived in France, wrote in 1765,

"The real spirit of the laws in France is that bureaucracy of which the late Monsieur de Gournay used to complain so greatly; here the offices, clerks, secretaries, inspectors and intendants are not appointed to benefit the public interest, indeed the public interest appears to have been established so that offices might exist."[49]

Cynicism over "officialdom" is still common, and the workings of public servants is often contrasted to private enterprise driven by the profit motive.[50] Writing in the early 20th century, Max Weber believed that a definitive feature of a developed state had come to be its bureaucratic support[48]. The stereotypical bureaucracy involves armies of white collared workers controlling and producing information, bound in 'red tape'. However state agencies also play a positive role, in redistributing resources at the wish of the elected representatives, which is collected from taxation, or organising crucial public services such as schooling, health care, policing or public transport.

Legal profession

Practice of law is typically overseen by either a government organization or independent regulating body such as a bar association, bar council, barrister society, or law society. To practice law, the regulating body must certify the practitioner. This usually entails a two or three-year program at a university faculty of law or a law school, which earns the student a Bachelor of Laws, a Bachelor of Civil Law or a Juris Doctor degree. This course of study is followed by an entrance examination (e.g. bar admission). Some countries require a further vocational qualification before a person is permitted to practice law. In the case of those wishing to become a barrister, this would lead to a Barrister-at-law degree, followed by a year's apprenticeship (sometimes known as pupillage or devilling) under the oversight of an experienced barrister (or master). Advanced law degrees are also often pursued, though they are academic degrees and are not required for the practice of law. These include a Master of Laws, a Master of Legal Studies, and a Doctor of Laws.

Once accredited, a lawyer will often work in a law firm, in a chambers, as a sole practitioner, for a government or as internal counsel at a private corporation. Another option is to become a legal researcher who provides on-demand legal research through a commercial service or on a freelance basis. Many people trained in law put their skills to use outside the legal field entirely. A significant component to the practice of law in the common law tradition involves legal research in order to determine the current state of the law. This usually entails exploring case-law reports, legal periodicals and legislation. Law practice also involves drafting documents such as court pleadings, persuasive briefs, contracts, or wills and trusts. Negotiation and dispute resolution skills are also important parts of legal practice, depending on the field.

Civil society

Perhaps the most crucial institution in the law is simply the civil partnerships and associations of ordinary people holding no official positions. Freedom of Speech, and Freedom of Association are our human rights, our civil liberties and most developed and developing countries uphold them. They form the basis of an active, thoughtful and deliberative democracy. The more people are involved with and concerned by how political power is exercised over their lives, the more acceptable and legitimate the law becomes to the people. Developed political parties or debating clubs, trade unions, impartial media, charities and perhaps even online encyclopedias are signs of a healthy civil society.

The term "civil society" traces back to Adam Ferguson, who saw the development of a "commercial state" as a way to change the corrupt feudal order and strengthen the liberty of the individual.[51] Later on, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a German philosopher, made the distinction between society and the 'state' in his Elements of the Philosophy of Right.[52] Hegel thought civil society (Zivilgesellschaft) was a stage on the dialectical relationship between Hegel's perceived opposites, the macro-community of the state and the micro-community of the family.[53]

Further reading

- Blackstone, William, Sir. An analysis of the laws of England: to which is prefixed an introductory discourse on the study of the law. 3rd ed. Buffalo, N.Y.: W.S. Hein & Co., 189 pp., 1997. (originally published: Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1758) ISBN 1-57588-413-5

- David, René, and John E. C. Brierley. Major Legal Systems in the World Today: An Introduction to the Comparative Study of Law. 3d ed. London: Stevens, 1985. ISBN 0-420-47340-8.

- Ginsburg, Ruth B. A selective survey of English language studies on Scandinavian law. So. Hackensack, N.J.: F. B. Rothman, 53 pp., 1970. OCLC 86068

- Glenn, H. Patrick Legal Traditions of the World: Sustainable Diversity in Law 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 432 pp., 2004. ISBN 0-19-926088-5

- Iuul, Stig, et al. Scandinavian legal bibliography. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 196 pp., 1961. (series: Acta / Instituti Upsaliensis Iurisprudentiae Comparativae; 4) OCLC 2558738

- Llewellyn, Karl N. & E. Adamson Hoebel. Cheyenne Way: Conflict & Case Law in Primitive Jurisprudence. special ed. New York City: Legal Classics Library, 374 pp., 1992. ISBN 0-8061-1855-5

- Nielsen, Sandro. The Bilingual LSP Dictionary. Principles and Practice for Legal language. Tübingeb.: Gunter Narr Verlag, 308 pp., 1994. (series: Forum für Fachsprachen-Forschung; Bd. 24) ISBN 3-8233-4533-8

External links

- Judicial sources

- House of Lords Judgments Page

- The German Federal Constitutional Court's Judgments Page

- The European Court of Justice Webpage

- The European Court of Human Rights' Webpage

- The United States Supreme Court Webpage

- Other sources

- Find Law

- FindUSLaw: United States Employment Law

- The Australian Institute of Comparative Legal Systems

- WorldLII - The World Legal Information Institute

- WikiCities Legal Site

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- The shared law in Jurispedia

- The Roman Law Library

- JURIST - Legal News & Research

- Legal Articles & Advice

|

| Law Articles |

|---|

| Jurisprudence |

| Law and legal systems |

| Legal profession |

| Types of Law |

| Administrative law |

| Antitrust law |

| Aviation law |

| Blue law |

| Business law |

| Civil law |

| Common law |

| Comparative law |

| Conflict of laws |

| Constitutional law |

| Contract law |

| Criminal law |

| Environmental law |

| Family law |

| Intellectual property law |

| International criminal law |

| International law |

| Labor law |

| Maritime law |

| Military law |

| Obscenity law |

| Procedural law |

| Property law |

| Tax law |

| Tort law |

| Trust law |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hart, H.L.A. (1961). The Concept of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN ISBN 0-19-876122-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dworkin, Ronald (1986). Law's Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN ISBN-10: 0674518365.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Raz, Joseph (1979). The Authority of Law. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Austin, John (1831). The Providence of Jurisprudence Determined.

- ↑ Aristotle (c.350B.C.E.) Politics: A Treatise on Government Book 3, Ch. XVI n.b. this translation reads, "it is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens"

- ↑ France, Anatole (1894) The Red Lily (Le lys rouge) n.b. the original French is, "La loi, dans un grand souci d'égalité, interdit aux riches comme aux pauvres de coucher sous les ponts, de mendier dans les rues et de voler du pain."

- ↑ see Etymonline Dictionary

- ↑ C-26/62 Van Gend en Loos v. Nederlanse Administratie Der Belastingen. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- ↑ Entick v. Carrington (1765) 19 Howell's State Trials 1030

- ↑ Locke, John (1690)Second Treatise on Government Chapter 9, Line 124

- ↑ Regina v. Dudley and Stephens ([1884] 14 QBD 273 DC)

- ↑ Wehberg, Hans (Oct., 1959) Pacta Sunt Servanda, The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 53, No. 4 , p.775; access at JSTOR

- ↑ e.g. In England, s.52 Law of Property Act 1925

- ↑ Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1893] 2 QB 256

- ↑ e.g. In Germany, § 311 Abs. II BGB

- ↑ Austotel v. Franklins (1989) 16 NSWLR 582

- ↑ § 105 Abs. II BGB

- ↑ Bolton v. Stone [1951] A.C. 850

- ↑ Sturges v. Bridgman (1879) 11 Ch D 852

- ↑ e.g. concerning a British politician and the Iraq war, Galloway v. Telegraph Group Ltd [2004] EWHC 2786

- ↑ Taff Vale Railway Co. v. Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants [1901] AC 426

- ↑ in the U.K., Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992; c.f. in the U.S., National Labor Relations Act

- ↑ Donoghue v. Stevenson [1932] AC 532

- ↑ Hunter v. Canary Wharf Ltd. (1997) 2 AllER 426.

- ↑ von Savigny, Friedrich, Das Recht des Besitzes (1803) See here [1] for the German text

- ↑ Matthews, Paul, The Man of Property [1995] 3 Med Law Rev 251-274

- ↑ Locke, John (1690) Second Treatise on Civil Government Ch. 9, s. 123 available here

- ↑ Proudhon, Pierre (1840). What is Property? or An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government (Qu'est-ce que la propriété? ou Recherche sur le principe du Droit et du Gouvernment).

- ↑ c.f. Bristol and West Building Society v. Mothew [1998] Ch 1

- ↑ Keech v. Sandford (1726) Sel Cas. Ch.61

- ↑ Nestle v. National Westminster Bank plc [1993] 1 WLR 1260

- ↑ Berle, Adolf (1932). Modern Corporation and Private Property.

- ↑ Magna Carta. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ VerSteeg, Russ (2002) Law in Ancient Egypt ISBN 0-89089-978-9

- ↑ Kant, Immanuel, Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals in Lewis White Beck, Königliche Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften Berlin, 1902-1938

- ↑ Kelsen, Hans (1934). Pure Theory of Law.

- ↑ ch. 2, Joseph Raz, The Authority of Law (1979) Oxford University Press

- ↑ Coase, Ronald, The Nature of the Firm (1937) Economica, New Series, Vol. 4, No. 16 (Nov., 1937), pp. 386-405

- ↑ Coase, Ronald, The Problem of Social Cost, J. Law & Econ. 3, p. 1 (1960)

- ↑ Sturges v. Bridgman (1879) 11 Ch D 852

- ↑ Locke, John (1690) Second Treatise on Civil Government available here

- ↑ de Montesquieu, Baron (1748). De l'esprit des lois.

- ↑ U.S. Supreme Court. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ House of Lords Judgments. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ European Court of Justice. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ The German Federal Constitutional Court. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ La Préfecture de Police. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Weber, Max (1919). Politik als Beruf.

- ↑ Melchior, Friedrich and Diderot, Denis (1813 Ed.) Correspondence littéraire, philosophique et critique, 1753-69 Vol. 4, p. 146 & 508 - cited by Albrow, Martin (1970) Bureaucracy p. 16

- ↑ von Mises, Ludwig [1944] (1962). Bureaucracy. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ An Essay on the History of Civil Society (1767)

- ↑ Etext of Philosophy of Right Hegel (1827) translated by Dyde, 1897

- ↑ Pelczynski, A.Z. (1984) The State and Civil Society pp.1-13 Cambridge University Press