Carter, Jimmy

| (126 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{approved}}{{images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{2Copyedited}} |

| − | {{Infobox | + | {{epname|Carter, Jimmy}} |

| − | | name =James Earl Carter, Jr | + | |

| − | | image=Jimmy Carter.jpg|200px | + | {{Infobox President_Living |

| + | | name =James Earl Carter, Jr. | ||

| + | | image name =Jimmy Carter.jpg|200px | ||

| order=39th [[President of the United States]] | | order=39th [[President of the United States]] | ||

| − | | | + | | date1=January 20, 1977 |

| − | | | + | | date2=January 20, 1981 |

| − | | | + | | preceded=[[Gerald Ford]] |

| − | | | + | | succeeded=[[Ronald Reagan]] |

| − | | | + | | date of birth=October 1, 1924 |

| − | | | + | | place of birth=Plains, Georgia |

| − | | | + | | wife=Rosalynn Smith Carter<br>(m. 1946; died 2023) |

| − | | party= | + | | party=Democratic |

| − | | vicepresident= | + | | vicepresident=Walter Mondale |

| religion=[[Baptist]] | | religion=[[Baptist]] | ||

| − | | | + | | |

|}} | |}} | ||

| − | '''James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr.''' (born October 1, 1924) was the 39th [[President of the United States]] (1977–1981) and | + | '''James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr.''' (born October 1, 1924) was the 39th [[President of the United States]] (1977–1981) and a [[Nobel Peace Prize|Nobel Peace laureate]]. Previously, he was the Governor of [[Georgia]] (1971–1975). In 1976, Carter won the Democratic nomination as a dark horse candidate, and went on to defeat incumbent [[Gerald Ford]] in the close 1976 presidential election. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As President, his major accomplishments included the consolidation of numerous governmental agencies into the newly-formed [[Department of Energy]], a cabinet level department. He enacted strong environmental legislation, deregulated the trucking, airline, rail, finance, communications, and oil industries, bolstered the [[Social Security]] system, and appointed record numbers of women and minorities to significant government and judicial posts. In foreign affairs, Carter's accomplishments included the [[Camp David Accords]], the [[Panama Canal Treaties]], the creation of full diplomatic relations with the [[People's Republic of China]], and the negotiation of the SALT II Treaty. In addition, he championed [[human rights]] throughout the world as the center of his foreign policy. | |

| − | The [[Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]] marked the end of détente, and Carter | + | During his term, however, the [[Iran]]ian hostage crisis was a devastating blow to national prestige; Carter struggled for 444 days without success to release the hostages. A failed rescue attempt led to the resignation of his Secretary of State [[Cyrus Vance]]. The hostages were finally released the day Carter left office, 20 minutes after President [[Ronald Reagan]]'s inauguration. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | In the [[Cold War]], the [[Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]] marked the end of détente, and Carter boycotted the Moscow Olympics and began to rebuild American military power. He beat off a primary challenge from Senator [[Ted Kennedy]] but was unable to combat severe stagflation in the U.S. economy. The "Misery Index," his favored measure of economic well-being, rose 50 percent in four years. Carter feuded with the Democratic leaders who controlled Congress and was unable to reform the [[tax]] system or implement a [[national health plan]]. | ||

| − | After 1980, Carter assumed the role of | + | After 1980, Carter assumed the role of elder statesman and international mediator, using his prestige as a former president to further a variety of causes. He founded the Carter Center, for example, as a forum for issues related to [[democracy]] and [[human rights]]. He has also traveled extensively to monitor elections, conduct peace negotiations, and coordinate relief efforts. In 2002, Carter won the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] for his efforts in the areas of international conflicts, human rights, and economic and social development. Carter has continued his decades-long active involvement with the charity [[Habitat for Humanity]], which builds houses for the needy. |

| − | ==Early | + | ==Early Years== |

| − | Carter | + | James Earl (Jimmy) Carter, Jr., the first President born in a hospital, was the oldest of four children of James Earl and Lillian Carter. He was born in the southwest [[U.S. state|Georgia]] town of Plains and grew up in nearby Archery, Georgia. Carter was a gifted student from an early age who always had a fondness for reading. By the time he attended Plains High School, he was also a star in basketball and football. Carter was greatly influenced by one of his high school teachers, Julia Coleman. Ms. Coleman, who was handicapped by polio, encouraged young Jimmy to read ''War and Peace.'' Carter claimed he was disappointed to find that there were no [[cowboy]]s or [[native Americans|Indians]] in the book. Carter mentioned his beloved teacher in his inaugural address as an example of someone who beat overwhelming odds. |

| − | + | Carter had three younger siblings, one brother and two sisters. His brother, Billy (1937–1988), would cause some political problems for him during his administration. One sister, Gloria (1926–1990), was famous for collecting and riding [[Harley-Davidson]] [[motorcycle]]s. His other sister, Ruth (1929–1983), became a well-known [[Christianity|Christian]] [[evangelist]]. | |

| − | Carter | + | After graduating from high school, Jimmy Carter attended Georgia Southwestern College and the Georgia Institute of Technology. He received a [[Bachelor of Science]] degree from the [[United States Naval Academy]] in 1946. He married Rosalynn Carter later that year. At the Academy, Carter had been a gifted student finishing 59th out of a class of 820. Carter served on submarines in the [[Atlantic Ocean|Atlantic]] and [[Pacific Ocean|Pacific]] fleets. He was later selected by Admiral [[Hyman G. Rickover]] for the [[United States Navy]]'s fledgling [[nuclear power|nuclear]] [[submarine]] program, where he became a qualified command officer.<ref> Rod Adams, [https://atomicinsights.com/picking-on-the-jimmy-carter-myth/ Picking on the Jimmy Carter Myth] ''Atomic Insights'', January 27, 2006. Retrieved January 3, 2024. </ref> Carter loved the Navy, and had planned to make it his career. His ultimate goal was to become [[Chief of Naval Operations]], but after the death of his father, Carter chose to resign his commission in 1953 when he took over the family's peanut farming business. |

| − | + | From a young age, Carter showed a deep commitment to [[Christianity]], serving as a Sunday School teacher throughout his political career. Even as [[United States President|President]], Carter prayed several times a day, and professed that [[Jesus of Nazareth|Jesus Christ]] was the driving force in his life. Carter had been greatly influenced by a sermon he had heard as a young man, called, "If you were arrested for being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?" <ref>Jimmy Carter, Don Richardson (ed.), ''Conversations with Carter'' (Lynne Rienner Pub, 1998, ISBN 978-1555878016).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | After [[World War II]] and during Carter's time in the Navy, he and Rosalynn started a family. They had three sons: John William, born in 1947; James Earl III, born in 1950; and Donnel Jeffrey, born in 1952. The couple also had a daughter, Amy Lynn, who was born in 1967. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The couple celebrated their 77th anniversary on July 7, 2023. On October 19, 2019, they became the longest-wed presidential couple, having overtaken George and Barbara Bush at 26,765 days. After Rosalynn's death on November 19, 2023, Carter released the following statement: | |

| + | <blockquote>Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished. She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.<ref>[https://www.cartercenter.org/news/pr/2023/statement-rosalynn-carter-111923.html Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter Passes Away at Age 96] ''The Carter Center'', November 19, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2023.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ==Early Political Career== | |

| + | ===Georgia State Senate=== | ||

| − | + | Carter began his political career by serving on various local boards, governing such entities as the [[school]]s, [[hospital]], and [[library]], among others. | |

| − | |||

| − | Carter | ||

| − | + | In 1962, Carter was elected to the [[Georgia]] state senate. He wrote about that experience, which followed the end of Georgia's County Unit System (per the Supreme Court case of Gray v. Sanders), in his book ''Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age.'' The election involved widespread corruption led by Joe Hurst, the sheriff of Quitman County (Examples of fraud included people voting in alphabetical order and dead people voting). It took a legal challenge on Carter's part for him to win the election. Carter was reelected in 1964 to serve a second two-year term. | |

| − | ===Campaign for | + | ===Campaign for Governor=== |

| − | In 1966, at the end of his career as a state senator, he | + | In 1966, at the end of his career as a state senator, he considered running for the [[United States House of Representatives]]. His [[United States Republican party|Republican]] opponent dropped out and decided to run for Governor of Georgia. Carter did not want to see a Republican as the governor of his state and in turn dropped out of the race for [[United States Congress]] and joined the race to become governor. Carter lost the [[United States Democratic party|Democratic]] primary, but drew enough votes as a third place candidate to force the favorite, Ellis Arnall, into a run-off, setting off a chain of events which resulted in the election of [[Lester Maddox]]. |

| − | For the next four years, Carter returned to his peanut farming business and carefully planned for his next campaign for governor in 1970, making over 1,800 speeches throughout the state. | + | For the next four years, Carter returned to his [[peanut]] [[farming]] business and carefully planned for his next campaign for governor in 1970, making over 1,800 speeches throughout the state. |

| − | During his 1970 campaign, he ran an uphill | + | During his 1970 campaign, he ran an uphill populist campaign in the Democratic primary against former Governor Carl Sanders, labeling his opponent "Cufflinks Carl." Although Carter had never been a segregationist; he had refused to join the segregationist White Citizens' Council, prompting a [[boycott]] of his peanut warehouse, and he had been one of only two families which voted to admit [[African American]]s to the Plains Baptist Church, he "said things the segregationists wanted to hear," according to historian E. Stanly Godbold.<ref> E. Stanly Godbold, Jr., ''Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter: The Georgia Years, 1924–1974'' (Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0199753444).</ref> Carter did not condemn [[Alabama]]n firebrand [[George Wallace]], and chastised Sanders for not inviting Wallace to address the [[State Assembly]] during his tenure as Governor. Following his close victory over Sanders in the primary, he was elected governor over Republican Hal Suit. |

==Governor== | ==Governor== | ||

| − | After having run a campaign in which he promoted himself as a traditional southern conservative, Carter surprised the state and gained national attention by declaring in his inaugural speech that the time of [[racial segregation]] was over, and that [[racism | + | After having run a campaign in which he promoted himself as a traditional southern conservative, Carter surprised the state and gained national attention by declaring in his inaugural speech that the time of [[racial segregation]] was over, and that [[racism]] had no place in the future of the state.<ref>[https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/jimmy-carter-b-1924/ Jimmy Carter (b. 1924)] ''The New Georgia Encyclopedia''. Retrieved January 3, 2024. </ref> He was the first statewide office holder in the Deep South to say this in public (such sentiments would have signaled the end of the political career of politicians in the region less than 15 years earlier, as had been the fate of Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., who had testified before Congress in favor of the [[Voting Rights Act]]). Following this speech, Carter appointed many blacks to statewide boards and offices; he hung a photo of [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] in the State House, a significant departure from the norm in the South.<ref>Peter G. Bourne, ''Jimmy Carter: A Comprehensive Biography from Plains to Post-Presidency'' (New York: Scribner, 1997, ISBN 0684195437).</ref> |

| − | Carter bucked the tradition of the "[[New Deal]] Democrat | + | Carter bucked the tradition of the "[[New Deal]] Democrat" attempting a retrenchment, in favor of shrinking government. As an environmentalist, he opposed many public works projects. He particularly opposed the construction of large dams for construction's sake, opting to take a pragmatic approach based on a cost-benefits analysis. |

| − | + | While Governor, Carter made government more efficient by merging about 300 state agencies into 30 agencies. One of his aides recalled that Governor Carter "was right there with us, working just as hard, digging just as deep into every little problem. It was his program and he worked on it as hard as anybody, and the final product was distinctly his."<ref>James T. Wooten, [https://www.nytimes.com/1976/05/17/archives/new-jersey-pages-carters-record-as-georgia-governor-activism-and.html Carter's Record as Georgia Governor: Activism and Controversial Programs] ''The New York Times'' (May 17, 1976). Retrieved January 3, 2024.</ref> He also pushed reforms through the legislature, providing equal state aid to schools in the wealthy and poor areas of Georgia, set up community centers for mentally handicapped children, and increased educational programs for convicts. At Carter's urging, the legislature passed laws to protect the environment, preserve historic sites, and decrease secrecy in government. Carter took pride in a program he introduced for the appointment of judges and state government officials. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit, rather than political influence. | |

| − | |||

| − | In 1972, as U.S. Senator [[George McGovern]] of [[South Dakota]] was marching toward the Democratic nomination for President, Carter called a news conference in Atlanta to warn that McGovern was unelectable. Carter criticized McGovern as too liberal on both foreign and domestic policy. The remarks attracted little national attention, and after McGovern's huge loss in the general election, Carter's attitude was not held against him within the Democratic Party. | + | In 1972, as U.S. Senator [[George McGovern]] of [[South Dakota]] was marching toward the Democratic nomination for President, Carter called a news conference in Atlanta to warn that McGovern was unelectable. Carter criticized McGovern as being too liberal on both foreign and domestic policy. The remarks attracted little national attention, and after McGovern's huge loss in the general election, Carter's attitude was not held against him within the Democratic Party. |

| − | After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Georgia's death penalty law in 1972, Carter signed new legislation to authorize the death penalty for murder, rape and other offenses and to implement trial procedures which would conform to the newly-announced constitutional requirements. | + | After the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] overturned [[Georgia]]'s death penalty law in 1972 in the ''Furman v. Georgia'' case, Carter signed new legislation to authorize the [[death penalty]] for [[murder]], [[rape]] and other offenses and to implement trial procedures which would conform to the newly-announced constitutional requirements. The Supreme Court upheld the law in 1976. |

In 1974, Carter was chairman of the [[Democratic National Committee]]'s congressional and gubernatorial campaigns. | In 1974, Carter was chairman of the [[Democratic National Committee]]'s congressional and gubernatorial campaigns. | ||

| − | ==1976 | + | ==1976 Presidential Campaign== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

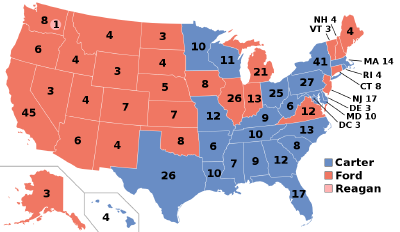

| − | + | [[File:ElectoralCollege1976.png|thumb|400px|The electoral map of the 1976 election.]] | |

| + | Carter began running for President in 1975, almost immediately upon leaving office as governor of Georgia. When Carter entered the [[United States Democratic Party|Democratic Party]] presidential primaries in 1976, he was considered to have little chance against nationally better-known politicians. When he told his family of his intention to run for president, he was asked, "President of what?" However, the [[Watergate scandal]] was still fresh in the voters' minds, and so his position as an outsider, distant from [[Washington, D.C.]], became an asset. Government reorganization, the hallmark of his time as governor, became the main plank of his campaign platform. | ||

| − | In | + | Carter became the front-runner early on by winning the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. He used a two-prong strategy. In the South, which most had tacitly conceded to Alabama's [[George Wallace]], Carter ran as a moderate favorite son. When Wallace proved to be a spent force, Carter swept the region. In the North, Carter appealed largely to conservative [[Christian]] and rural voters and had little chance of winning a majority in most states. But in a field crowded with liberals, he managed to win several Northern states by building the largest single bloc. Initially dismissed as a regional candidate, Carter proved to be the only Democrat with a truly national strategy, and he eventually clinched the nomination. |

| − | + | The media discovered and promoted Carter. As Laurence Shoup noted in his 1980 book, ''The Carter Presidency And Beyond'': | |

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | What Carter had that his opponents did not was the acceptance and support of elite sectors of the mass communications media. It was their favorable coverage of Carter and his campaign that gave him an edge, propelling him rocket-like to the top of the opinion polls. This helped Carter win key primary election victories, enabling him to rise from an obscure public figure to President-elect in the short space of 9 months.<ref name=Shoup>Laurence H. Shoup, ''The Carter Presidency and Beyond: Power and Politics in the 1980's'' (Ramparts Press, 1979, ISBN 0878670750).</ref> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | As late as January 26, 1976, Carter was the first choice of only 4 percent of Democratic voters, according to the [[Gallup Poll]]. Yet, "by mid-March 1976, Carter was not only far ahead of the active contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination, he also led President Ford by a few percentage points."<ref name=Shoup/> | ||

| − | + | The news media aided Carter's ascendancy. In November 1975, the ''New York Times'' printed an article, titled "Carter's Support In South Is Broad." The following month, the ''Times'' continued to promote Carter's candidacy by publishing a cover story on him in the December 14, 1975 ''[[New York Times]] Magazine'' of its Sunday edition. Shoup argues that "The ''Times'' coverage of several other candidates during this period, just before the Iowa caucuses, stands in sharp contrast to the favoritism shown Carter."<ref name=Shoup/> | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | In the general election, Carter started with a huge lead over incumbent President [[Gerald Ford]], but Ford steadily closed the gap in the polls. The cause of this erosion appeared to be public doubt about such a little-known candidate. But Carter hung on to narrowly defeat Ford in the November 1976 election. He became the first contender from the Deep South to be elected President since 1848. His 50.1 percent of the popular vote made him one of only two Democratic Party presidential candidates to win a majority of the popular vote since [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] in 1944. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Presidency (1977 – 1981)== | |

| + | ===Energy Crisis=== | ||

| + | The oil crisis of 1979 (as a result of the Iranian Revolution) was one of the most difficult parts of the Carter presidency. When the energy market collapsed, Carter had been planning on delivering his fifth major speech on energy. Despondent after the shock, however, Carter came to feel that the American people were no longer listening. Instead of delivering his planned speech, he went to Camp David and for ten days met with governors, mayors, religious leaders, scientists, economists, and general citizens. He sat on the floor and took notes of their comments and especially wanted to hear criticism. His pollster told him that the American people simply faced a crisis of confidence because of the assassination of [[John F. Kennedy]], the [[Vietnam War]], and [[Watergate Scandal|Watergate]]. Vice President [[Walter Mondale]] strongly objected and said that there were real answers to the real problems faced by the country; it did not have to be a philosophical question. | ||

| − | + | On July 15, 1979, Carter gave a nationally-televised address in which he identified what he believed to be a "crisis of confidence" among the American people. This came to be known as his "malaise" speech, even though he did not use the word "malaise" anywhere in the text: | |

| + | <blockquote>I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy…. I do not refer to the outward strength of America, a nation that is at peace tonight everywhere in the world, with unmatched economic power and military might.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.<ref>Jimmy Carter, [https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/jimmycartercrisisofconfidence.htm Energy and the National Goals - A Crisis of Confidence] ''American Rhetoric'' (July 15, 1979). Retrieved January 3, 2024.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | Carter's speech, written by Chris Matthews, was well-received in some quarters but not so well in others.<ref>Adam Clymer, [https://www.nytimes.com/1979/07/18/archives/speech-lifts-carter-rating-to-37-public-agrees-on-confidence-crisis.html Speech Lifts Carter Rating to 37%; Public Agrees on Confidence Crisis] ''New York Times'' magazine (July 18, 1979). Retrieved January 3, 2024.</ref> Many citizens were disappointed that the president hadn't detailed any concrete solutions. Two days after the speech, Carter asked for the resignations of all of his Cabinet officers, and ultimately accepted five. Carter later admitted in his memoirs that he should have simply asked only those five members for their resignation. By asking the entire Cabinet, it looked as if the White House was falling apart. With no visible efforts towards a way out of the malaise, Carter's poll numbers dropped even further. | |

| − | + | Carter saw a new, conservation-minded U.S. energy policy as one possible solution to the OPEC-induced crisis. He convinced Congress to create the United States Department of Energy, which produced policies to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil. Following its recommendations to conserve energy, Carter wore sweaters, installed [[solar power]] panels on the roof of the White House, installed a wood stove in the living quarters, ordered the General Services Administration to turn off hot water in some facilities, and requested that [[Christmas]] decorations remain dark in 1979 and 1980. Nationwide controls were put on thermostats in government and commercial buildings to prevent people from raising temperatures in the winter or lowering them in summer. | |

| − | ===Domestic | + | ===Domestic Policy=== |

| − | + | ====Economy==== | |

| + | [[Image:The Shah with Atherton, Sullivan, Vance, Carter and Brzezinski, 1977.jpg|right|thumb|400px|The Iranian Shah, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]] meeting with Arthur Atherton, [[William H. Sullivan]], [[Cyrus Vance]], President Jimmy Carter, and [[Zbigniew Brzezinski]], 1977]] | ||

| + | During Carter's term, the American economy suffered double-digit [[inflation]], coupled with very high interest rates, oil shortages, high unemployment, and slow economic growth. Nothing the president did seemed to help, as the indices on Wall Street continued the slide that had started in the mid-1970s. | ||

| − | + | To stem [[inflation]], the [[Federal Reserve Board]] raised interest rates to unprecedented levels (above 12 percent per year). The prime rate hit 21.5 in December 1980. The rapid change in rates led to disintermediation of bank deposits, which began the [[savings and loan]] crisis. Investments in fixed income (both bonds and pensions being paid to retired people) were becoming less valuable. With the markets for U.S. government debt coming under pressure, Carter appointed [[Paul Volcker]] as Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Volcker took actions (raising interest rates even further) to slow down the economy and bring down inflation, which he considered his mandate. He succeeded, but only by first going through a very unpleasant phase where the economy slowed down, causing a rise in unemployment, prior to any relief from the inflation. | |

| − | + | Carter's government reorganization efforts separated the Department of Health, Education and Welfare into the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services]]. Even though many departments were consolidated during Carter's presidency, the total number of Federal employees continued to increase, despite his promises to the contrary. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | On a more successful note, Carter signed legislation bolstering the [[Social Security system]] through a staggered increase in the payroll tax and appointed record numbers of women, blacks, and Hispanics to government and judiciary jobs. Carter signed strong legislation for environmental protection. His [[Alaska]] National Interest Lands Conservation Act created 103 million acres of national park land in Alaska. He was also successful in deregulating the trucking, rail, airline, communications, oil, and finance industries. | |

| − | + | ===Foreign policy=== | |

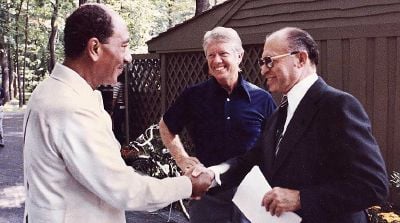

| + | [[Image:Begin, Carter and Sadat at Camp David 1978.jpg|thumb|400px|right|Celebrating the signing of the [[Camp David Accords (1978)]]: [[Menachem Begin]], Jimmy Carter, [[Anwar Sadat]]]] | ||

| − | + | Carter's time in office was marked by increased U.S.-led diplomatic and peace-building efforts. One of Carter's first acts was to announce his intention to remove all U.S. troops from [[South Korea]], although ultimately he did not follow through. Fitting with his "dovish" foreign policy stance, Carter cut the defense budget by $6 billion within months of assuming office. | |

| − | President Carter initially departed from the long-held policy of [[containment]] toward the [[Soviet Union]]. In its place Carter promoted a foreign policy that placed [[human rights]] at the forefront. This was a break from the policies of several predecessors, in which | + | President Carter initially departed from the long-held policy of [[containment]] toward the [[Soviet Union]]. In its place, Carter promoted a foreign policy that placed [[human rights]] at the forefront. This was a break from the policies of several predecessors, in which human rights abuses were often overlooked if they were committed by a nation that was allied with the United States. For example, the Carter Administration ended support to the historically U.S.-backed Somoza dictatorship in [[Nicaragua]], and gave millions of dollars in aid to the nation's new [[Sandinista]] regime after it rose to power in a revolution. The Sandinistas were Marxists who quickly moved toward authoritarianism. They formed close ties (in terms of weapons, politics and logistics) with [[Cuba]], but Carter showed a greater interest in human and social rights than in the historical U.S. conflict with Cuba. |

| − | Carter continued his predecessors' policies of imposing sanctions on [[Rhodesia]], and, after Bishop [[Abel Muzorewa]] was elected Prime Minister, protested that the Marxists [[Robert Mugabe]] and | + | Carter continued his predecessors' policies of imposing sanctions on what was then called [[Zimbabwe|Rhodesia]], and, after Bishop [[Abel Muzorewa]] was elected Prime Minister, protested that the Marxists [[Robert Mugabe]] and Joshua Nkomo were excluded from the elections. Strong pressure from the United States and the [[United Kingdom]] prompted new elections. |

| − | Carter continued the policy of Richard Nixon to | + | Carter continued the policy of Richard Nixon to normalize relations with the [[People's Republic of China]] by granting full diplomatic and trade relations, thus ending official relations with the [[Republic of China]] (though the two nations continued to trade and the U.S. unofficially recognized [[Taiwan]] through the [[Taiwan Relations Act]]). Carter also succeeded in having the Senate ratify the [[Panama Canal Treaties]], which would hand over control of the canal to [[Panama]] in 1999. |

====Panama Canal Treaties==== | ====Panama Canal Treaties==== | ||

| − | One of the most controversial | + | One of the most controversial of President Carter's foreign policy measures was the final negotiation and signature of the [[Panama Canal Treaties]] in September 1977. Those treaties, which essentially would transfer control of the American-built Panama Canal to the strongman-led Republic of [[Panama]], were bitterly opposed by a large segment of the American public and by the Republican party. The most visible personality opposing the treaties was [[Ronald Reagan]], who would defeat Carter in the next presidential election. A powerful argument against the treaties was that the United States was transferring an American asset of great strategic value to an unstable and corrupt country led by a brutal military dictator ([[Omar Torrijos]]). After the signature of the Canal treaties, in June 1978, Jimmy Carter visited Panama with his wife and twelve U. S. Senators, amid widespread student disturbances against the Torrijos dictatorship. Carter then began urging the Torrijos regime to soften its policies and move Panama towards gradual democratization. However, Carter's efforts would prove ineffective and in 1989 the United States would have to launch a massive invasion of Panama to remove from power Torrijos's successor, strongman General [[Manuel Noriega]]. |

====Camp David Accords==== | ====Camp David Accords==== | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Camp David, Menachem Begin, Anwar Sadat, 1978.jpg|thumb|400px|right|[[Anwar Sadat]], Jimmy Carter, and [[Menachem Begin]] meet at Camp David in September, 1978.]] |

| + | |||

| + | President Carter and members of his administration, particularly Secretary of State [[Cyrus Vance]] and National Security Adviser [[Zbigniew Brzezinski]], were very concerned about the [[Arab-Israeli conflict]] and its widespread effects on the [[Middle East]]. After the [[Yom Kippur War]] of 1973, diplomatic relations between [[Israel]] and [[Egypt]] slowly improved, thus raising the possibility of some kind of agreement. The Carter administration felt that the time was right for a comprehensive solution to at least their part in the conflict. In 1978, President Carter hosted Israeli Prime Minister [[Menachem Begin]] and Egyptian President [[Anwar Sadat]] at [[Camp David]] for secret peace talks. Twelve days of difficult negotiations resulted in normalized relations between Israel and Egypt and an overall reduction in tension in the Middle East. | ||

| − | + | The [[Camp David Accords]] was perhaps the most important achievement of Carter's presidency. In these negotiations [[King Hassan II]] of [[Morocco]] acted as a mediator between Arab interests and Israel, and [[Nicolae Ceausescu]] of communist [[Romania]] acted as go-between between Israel and the [[Palestinian Liberation Organization]]. Once initial negotiations had been completed, Sadat approached Carter for assistance. Carter then invited Begin and Sadat to Camp David to continue the negotiations, with Carter, according to all accounts, playing a forceful role. At one point, Sadat had had enough and prepared to leave, but after prayer, Carter told Sadat he would be ending their friendship, and this act would also damage U.S.-Egyptian relations. Carter's earnest appeal convinced Sadat to stay. At another point, Begin too decided to back out of the negotiations, a move that Carter countered by offering to Begin signed photographs of himself for each of Begin's grandchildren. The gesture forced Begin to think about what [[peace]] would mean for his grandchildren and all future generations of Israeli children. To date, peaceful relations have continued between Israel and Egypt. | |

====Strategic Arms Limitations Talks==== | ====Strategic Arms Limitations Talks==== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Carter_Brezhnev_sign_SALT_II.jpg|thumb|400px|right||President Jimmy Carter and Soviet General Secretary [[Leonid Brezhnev]] sign the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II) treaty, June 18, 1979, in [[Vienna]].]] | |

| − | + | The SALT (Strategic Arms Limitations Talks) II Treaty between the U.S. and the [[Soviet Union]] was another significant aspect of Carter's foreign policy. The work of presidents [[Gerald Ford]] and [[Richard Nixon]] brought about the SALT I treaty, but Carter wished to further the reduction of nuclear arms. It was his main goal, as stated in his Inaugural Address, that nuclear weaponry be completely eliminated. Carter and [[Leonid Brezhnev]], General Secretary and leader of the Soviet Union, reached an agreement and held a signing ceremony. The Soviet invasion of [[Afghanistan]] in late 1979, however, led the Senate to refuse to ratify the treaty. Regardless, both sides honored the respective commitments laid out in the negotiations. | |

| − | [[Image:Carter_Brezhnev_sign_SALT_II.jpg|thumb| | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Hardening of U.S./Soviet Relations==== | |

| + | In late 1979, the Soviet Union invaded [[Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan|Afghanistan]]. The Carter Administration, and many other Democrats and even Republicans, feared that the Soviets were positioning themselves for a takeover of Middle Eastern [[oil]]. Others believed that the Soviet Union was fearful that a [[Muslim]] uprising would spread from [[Iran]] and Afghanistan to the millions of Muslims in the [[USSR]]. | ||

| − | + | After the invasion, Carter announced the Carter Doctrine: that the U.S. would not allow any outside force to gain control of the [[Persian Gulf]]. Carter terminated the Russian wheat deal, a keystone Nixon détente initiative to establish trade with USSR and lessen [[Cold War]] tensions. The grain exports had been beneficial to the Soviet people employed in agriculture, and the Carter embargo marked the beginning of hardship for American farmers. He also prohibited Americans from participating in the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and reinstated registration for the draft for young males. Carter and National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski started a $40 billion covert program to train Islamic [[fundamentalist]]s in [[Pakistan]] and Afghanistan. | |

| − | In | + | ====Iran Hostage Crisis==== |

| + | In Iran, the conflict between Carter's concern for human rights and U.S. interests in the region came to a head. The Shah of Iran, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]], had been a strong ally of America since [[World War II]] and was one of the "twin pillars" upon which U.S. strategic policy in the Middle East was built. However, his rule was strongly autocratic, and he had supported the plan of the [[Dwight Eisenhower|Eisenhower]] administration to depose Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and replace him as shah (king) in 1953. Though Carter praised the Shah as a wise and valuable leader, when a popular uprising against the monarchy broke out in Iran, the U.S. did not intervene. | ||

| − | The | + | The Shah was deposed and exiled. Some have since connected the Shah's dwindling U.S. support as a leading cause of his quick overthrow. Carter was initially prepared to recognize the revolutionary government of the monarch's successor, but his efforts proved futile. |

| − | + | On October 22, 1979, due to humanitarian concerns, Carter allowed the deposed shah into the United States for [[political asylum]] and medical treatment; the Shah left for Panama on December 15, 1979. In response to the Shah's entry into the U.S., Iranian militant students seized the American embassy in Tehran, taking 52 Americans hostage. The Iranians demanded: (1) the return of the Shah to Iran for trial; (2) the return of the Shah's wealth to the Iranian people; (3) an admission of guilt by the United States for its past actions in Iran, plus an apology; and, (4) a promise from the United States not to interfere in Iran's affairs in the future. Though later that year the Shah left the U.S. and died shortly thereafter in Egypt, the hostage crisis continued and dominated the last year of Carter's presidency, even though almost half of the hostages were released. The subsequent responses to the crisis—from a "Rose Garden" strategy" of staying inside the White House, to the unsuccessful military attempt to rescue the hostages—were largely seen as contributing to Carter's defeat in the 1980 election. | |

| − | |||

| − | On | ||

===Controversies=== | ===Controversies=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *Carter | + | *In 1977, Carter said that there was no need to apologize to the Vietnamese people for the damage and suffering caused by the [[Vietnam War]] because "the destruction was mutual." |

| − | + | *In 1977, Bert Lance, Carter's director of the Office of Management and Budget, resigned after past banking overdrafts and "check kiting" were investigated by the U.S. Senate. However, no wrongdoing was found in the performance of his duties. | |

| − | In | ||

| − | + | *Carter supported the Indonesian government even while it brutalized the civilian population in [[East Timor]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Supreme Court=== | |

| + | Among all United States Presidents who served at least one full term, Carter is the only one who never made an appointment to the Supreme Court. | ||

===1980 election=== | ===1980 election=== | ||

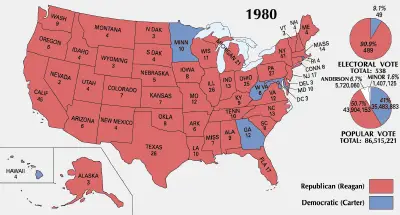

| − | + | [[image:ElectoralCollege1980-Large.png|thumb|400px|The electoral map of the 1980 election.]] | |

| − | [[image:ElectoralCollege1980-Large.png|thumb| | + | Carter lost the presidency by an electoral landslide to [[Ronald Reagan]] in the 1980 election. The popular vote went approximately 51 percent for Reagan and 41 percent for Carter. However, because Carter's support was not concentrated in any geographic region, Reagan won 91 percent of the electoral vote, leaving Carter with only six states and the [[District of Columbia]] in the [[Electoral College]]. Independent candidate [[John B. Anderson]], drawing liberals unhappy with Carter's policies, won seven percent of the vote and prevented Carter from taking traditionally Democratic states like [[New York]], [[Wisconsin]], and [[Massachusetts]]. |

| − | Carter lost the presidency by | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:WIKI JIMMY CARTER.jpg|thumb|right|400px|President Carter campaigning for re-election in October, 1980]] |

| + | In their televised debates, Reagan taunted Carter by famously saying, "There you go again." Carter also managed to hurt himself in the debates when he talked about asking his young daughter, Amy, what the most important issue affecting the world was. She said it was nuclear proliferation and the control of nuclear arms. Carter said that the point he was trying to make was that this issue affects everyone, especially our children. His phrasing, however, implied that he had been taking political advice from his 13-year-old daughter, which led to ridicule in the press. | ||

| − | + | A public perception that the Carter Administration had been ineffectual in addressing the Iranian hostage crisis also contributed to his defeat. Although the Carter team had successfully negotiated with the hostage takers for release of the hostages, an agreement trusting the hostage takers to abide by their word was not signed until January 19, 1981, after the election of Ronald Reagan. The hostages had been held captive for 444 days, and their release occurred just minutes after Carter left office. In a show of good will, Reagan asked Carter to go to West [[Germany]] to greet the hostages. | |

==Post-presidency== | ==Post-presidency== | ||

| − | [[Image:FordNixonBushReaganCarter.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:FordNixonBushReaganCarter.jpg|thumb|400px|right|Former Presidents [[Gerald Ford]], [[Richard Nixon]], then-President [[George H. W. Bush]], former Presidents [[Ronald Reagan]] and Jimmy Carter at the dedication of the Reagan Presidential Library]] |

| − | Since leaving the presidency, Carter | + | Since leaving the presidency, Jimmy Carter wrote numerous books. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Diplomacy=== | ===Diplomacy=== | ||

| − | In 1994, Carter went to [[North Korea]] at the | + | In 1994, Carter went to [[North Korea]] at the height of the first nuclear crisis when the North had expelled inspectors from the [[International Atomic Energy Agency]] (IAEA) and threatened to reprocess spent nuclear fuel. He traveled there as a private citizen, not an official U.S. envoy, but with the permission of then President [[Bill Clinton|Clinton]]. Under the premise that a major problem cannot be solved unless you meet with the top leader behind that problem, Carter met with North Korea's President [[Kim Il Sung]] and obtained an informal agreement that the North would freeze its nuclear program in exchange for provision of alternative energy. Carter's immediate announcement of this agreement on global [[CNN]] television preempted the [[White House]] from undertaking its own actions, which included bolstering American military forces and equipment in [[South Korea]]—actions which, according to many experts, could have compelled the North to launch a second [[Korean War]]. Based on Carter's unofficial negotiations, the U.S. signed in October 1994 the Agreed Framework, under which North Korea agreed to freeze its nuclear program in exchange for a process of normalizing relations, heavy fuel oil deliveries and two light water reactors to replace its graphite-moderated reactors. The Agreed Framework stood until late 2002 when the [[George W. Bush]] administration accused the North of running a clandestine uranium enrichment program and both sides then abandoned the agreement. |

| − | + | Carter visited [[Cuba]] in May 2002 and met with its president, [[Fidel Castro]]. He was allowed to address the Cuban public on national television with a speech that he wrote and presented in Spanish. This made Carter the first President of the United States, in or out of office, to visit the island since Castro's 1959 revolution. | |

| − | |||

| − | Carter visited [[Cuba]] in May 2002 and met with [[Fidel Castro]]. He was allowed to address the Cuban public on national television with a speech that he wrote and presented in Spanish. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Humanitarian work=== | ===Humanitarian work=== | ||

| − | Carter has been involved in a variety of national and international | + | Since his presidency, Carter has been involved in a variety of national and international public policy, conflict resolution, human rights and charitable causes through the [[Carter Center]]. He and his wife Rosalynn established the Carter Center the year following his term. The Center also focuses on world-wide health care including the campaign to eliminate [[guinea worm disease]]. He and members of the Center are often involved in the monitoring of the electoral process in support of free and fair elections. This includes acting as election observers, particularly in Latin America and Africa. |

| − | He and his wife are also well-known for their work with | + | He and his wife are also well-known for their work with Habitat for Humanity. |

| − | Carter was the third U.S. President, | + | Carter was the third U.S. President, in addition to [[Theodore Roosevelt]] and [[Woodrow Wilson]], to receive the [[Nobel Peace Prize]]. In his Nobel Lecture, Carter told the European audience that U.S. actions after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the 1991 Gulf War, like NATO itself, was a continuation of President Wilson's doctrine of collective security.<ref>Jimmy Carter, [https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2002/carter/lecture/ Nobel lecture] Oslo, December 10, 2002. ''The Nobel Prize''. Retrieved January 3, 2024.</ref> |

===American politics=== | ===American politics=== | ||

| + | In 2001, Carter criticized President [[Bill Clinton]]'s controversial pardon of commodities broker and financier Marc Rich who fled prosecution on tax evasion charges, calling it "disgraceful" and suggesting that Rich's contribution of $520 million to the Democratic Party was a factor in Clinton's action. | ||

| − | + | In March 2004, Carter condemned [[George W. Bush]] and British Prime Minister [[Tony Blair]] for waging an unnecessary war "based upon lies and misinterpretations" in order to oust [[Saddam Hussein]] in the 2003 invasion of [[Iraq]]. Carter claimed that Blair had allowed his better judgment to be swayed by Bush's desire to finish a war that [[George H. W. Bush]], his father, had begun. | |

| − | |||

| − | In March 2004, Carter condemned [[George W. Bush]] and [[Tony Blair]] for waging an unnecessary war "based upon lies and misinterpretations" in order to oust Saddam Hussein. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Additional accolades=== | ===Additional accolades=== | ||

| + | Carter has received honorary degrees from many American colleges, including [[Harvard University]], Bates College, and the [[University of Pennsylvania]]. | ||

| − | + | On November 22, 2004, [[New York]] Governor George Pataki named Carter and the other living former Presidents (Gerald Ford, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton) as honorary members of the board rebuilding the [[World Trade Center]] after the [[September 11 terrorist attacks]] destroyed the original structures. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | On November 22, 2004, New York | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Because he had served as a submariner (the only President to have done so), a submarine was named for him. The USS ''Jimmy Carter'' was christened on April 27, 1998, making it one of the very few U.S. Navy vessels to be named for a person still alive at the time of its christening. In February 2005, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter both spoke at the commissioning ceremony for this submarine. | |

| − | + | Carter is a University Distinguished Professor at [[Emory University]] and teaches occasional classes there. He also teaches a Sunday school class at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, [[Georgia]]. Being an accomplished amateur woodworker, he has occasionally been featured in the pages of ''Fine Wood Working'' magazine, which is published by Taunton Press. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Carter has also participated in many ceremonial events such as the opening of his own presidential library and those of Presidents [[Ronald Reagan]], [[George H.W. Bush]], and [[Bill Clinton]]. He has also participated in many forums, lectures, panels, funerals and other events. Most recently, he delivered a eulogy at the funeral of [[Coretta Scott King]], widow of [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]]. | |

| − | + | ==A Man of Faith== | |

| + | As a politician and in his extensive post-presidential work for peace and democracy, Carter has never hidden his deep Christian commitment. He upholds separation of church from state, for which Baptists have always stood but writes of how his "religious beliefs have been inextricably entwined with the political principles" he has adopted.<ref name=Endangered>Jimmy Carter, ''Our Endangered Values: America's Moral Crisis'' (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005, ISBN 9780743284578).</ref> He has had his critics. In 1980, the then president of the [[Southern Baptist]] Convention, visiting him in the White House, demanded to know when the President was going to "abandon secular humanism" as his religion. Carter, shocked, asked his own pastor why the president of his own denomination might have said this. His pastor replied that perhaps some of his presidential decisions "might be at odds with political positions espoused by leaders of the newly-formed [[Moral Majority]]." These could include the appointment of women to high office, working with "Mormons to resolve some … problems in foreign countries" and the normalization of relations with Communist China.<ref name=Endangered/> Carter himself believed that his policies and actions were consistent with traditional Baptist beliefs. | ||

| − | + | Carter has been active as a Baptist at local, national and international conferences. In 2005 he was a keynote speaker at the 100th anniversary Congress of the Baptist World Alliance, where he made a strong affirmation of women in ministry, distancing himself from the Southern Baptist Convention which does not permit women to hold the position of senior pastor. His concern for peace and justice in the Middle East has resulted in criticism of the activities and policies of conservative Christians, who have supported Jewish settlements in the [[West Bank]], for example. He is highly outspoken of his nation's increased use of force in the world, which he believes has diminished international respect for the United States and its ability to contribute to global stabilization. He points out that Christians have been in the forefront of "promoting the war in Iraq." A return to America's core values of "religious faith and historic ideals of peace, economic and political freedom, democracy and human rights" would greatly enhance the U.S.'s peacekeeping mission, in his view.<ref name=Endangered/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Honors== | ==Honors== | ||

| − | President Carter has | + | President Carter has received many honors in his life. Among the most significant were the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1999 and the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. Others include: |

| − | *LL.D. (Honorary) Morehouse College, 1972; Morris Brown College, 1972; University of Notre Dame, 1977; Emory University, 1979; Kwansei Gakuin University, 1981; Georgia Southwestern College, 1981; New York Law School, 1985; Bates College, 1985; Centre College, 1987; Creighton University, 1987; University of Pennsylvania, 1998 | + | *LL.D. (Honorary) Morehouse College, 1972; Morris Brown College, 1972; [[University of Notre Dame]], 1977; Emory University, 1979; Kwansei Gakuin University, 1981; Georgia Southwestern College, 1981; New York Law School, 1985; Bates College, 1985; Centre College, 1987; Creighton University, 1987; University of Pennsylvania, 1998 |

*D.E. (Honorary) Georgia Institute of Technology, 1979 | *D.E. (Honorary) Georgia Institute of Technology, 1979 | ||

*Ph.D. (Honorary) Weizmann Institute of Science, 1980; Tel Aviv University, 1983; Haifa University, 1987 | *Ph.D. (Honorary) Weizmann Institute of Science, 1980; Tel Aviv University, 1983; Haifa University, 1987 | ||

| Line 431: | Line 244: | ||

*The Hoover Medal, 1998 | *The Hoover Medal, 1998 | ||

*International Child Survival Award, UNICEF Atlanta, 1999 | *International Child Survival Award, UNICEF Atlanta, 1999 | ||

| − | *William Penn Mott, Jr., Park Leadership Award, National | + | *William Penn Mott, Jr., Park Leadership Award, National Parks Conservation Association, 2000 |

| − | == | + | ==Major Works== |

| − | + | A prolific author, Jimmy Carter has written the following: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Why Not the Best?'' Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1996. ISBN 1557284180 | |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''A Government as Good as Its People.'' Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1996. ISBN 1557283982 |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President.'' Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1995. ISBN 1557283303 |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Negotiation: The Alternative to Hostility.'' Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1984. ISBN 086554137X |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''The Blood of Abraham: Insights into the Middle East.'' Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1993. ISBN 1557282935 |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy and Carter, Rosalynn. ''Everything to Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life.'' Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1995. ISBN 1557283885 |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''An Outdoor Journal: Adventures and Reflections.'' Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1994. ISBN 1557283540 |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age.'' New York: Times Books, 1992. ISBN 0812920791 |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Talking Peace: A Vision for the Next Generation.'' New York: Dutton Children’s Books, 1995. ISBN 0525455175 |

| − | * | + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Always a Reckoning, and Other Poems.'' New York: Times Books, 1995. ISBN 0812924347 A collection of poetry, illustrated by Sarah Elizabeth Chuldenko. |

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''The Little Baby Snoogle-Fleejer.'' New York: Times Books, 1996. ISBN 0812927311 A children's book, illustrated by Amy Carter. | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Living Faith.'' New York: Times Books, 1998. ISBN 0812930347 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Sources of Strength: Meditations on Scripture for Daily Living.'' New York: Times Books: Random House, 1997. ISBN 0812929446 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''The Virtues of Aging.'' New York: Ballantine Pub. Group, 1998. ISBN 0345425928 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''An Hour before Daylight: Memories of a Rural Boyhood.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0743211936 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Christmas in Plains: Memories.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0743224914 Illustrated by Amy Carter. | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''The Nobel Peace Prize Lecture.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0743250680 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''The Hornet's Nest: a Novel of the Revolutionary War.'' Waterville, ME: Thorndike Press, 2004. ISBN 0786261544 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Sharing Good Times.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 9780743270687 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Our Endangered Values: America's Moral Crisis.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 9780743284578 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Palestine: Peace, Not Apartheid.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 978-0743285025 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Beyond the White House: Waging Peace, Fighting Disease, Building Hope.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007. ISBN 978-1416558804 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''A Remarkable Mother''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008. ISBN 978-1416562450 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''We Can Have Peace in the Holy Land: A Plan That Will Work''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009. ISBN 978-1439140635 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''White House Diary''. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010. ISBN 978-0374280994 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Through the Year with Jimmy Carter: 366 Daily Meditations from the 39th President''. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011. ISBN 978-0310330486 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''NIV Lessons from Life Bible: Personal Reflections with Jimmy Carter''. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012. ISBN 978-0310950813 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and Power''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014. ISBN 978-1476773957 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015. ISBN 978-1501115639 | ||

| + | *Carter, Jimmy. ''Faith: A Journey for All''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018. ISBN 978-1501184413 | ||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | * Bourne, Peter G. ''Jimmy Carter: A Comprehensive Biography from Plains to Post-Presidency.'' New York: Scribner, 1997. ISBN 0684195437 |

| − | * | + | * Brinkley, Douglas. ''The Unfinished Presidency: Jimmy Carter's Quest for Global Peace.'' New York: Penguin Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0670880065 |

| − | * | + | * Califano, Joseph A., Jr. ''Governing America: An insider's report from the White House and the Cabinet.'' New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. ISBN 0671254286 |

| − | * | + | * Carter, Jimmy, Don Richardson (ed.). ''Conversations with Carter''. Lynne Rienner Pub, 1998. ISBN 978-1555878016 |

| − | * | + | * Dumbrell, John. ''The Carter Presidency: A Re-evaluation.'' Manchester, UK; New York: Manchester University Press: Distributed in the USA and Canada by St. Martin’s Press, 1995. ISBN 0719046939 |

| + | * Fink, Gary, and Hugh Davis Graham (eds.). ''The Carter Presidency: Policy Choices in the Post-New Deal Era.'' Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998. ISBN 0700608958 | ||

| + | * Gillon, Steven M. ''The Democrats' Dilemma: Walter F. Mondale and the Liberal Legacy.'' New York: Columbia University Press, 1992. ISBN 0231076304 | ||

| + | * Glad, Betty. ''Jimmy Carter: In Search of the Great White House.'' New York: W. W. Norton, 1980. ISBN 0393075273 | ||

| + | * Godbold, E. Stanly, Jr. ''Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter: The Georgia Years, 1924–1974''. Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0199753444 | ||

| + | * Hargrove, Erwin C. ''Jimmy Carter as President: Leadership and the Politics of the Public Good.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988. ISBN 0807114995 | ||

| + | * Jones, Charles O. ''The Trusteeship Presidency: Jimmy Carter and the United States Congress.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988. ISBN 080711426X | ||

| + | * Jordan, Hamilton. ''Crisis: The Last Year of the Carter Presidency.'' New York: Putnam, 1982. ISBN 0399127380 | ||

| + | * Jordan, William John. ''Panama Odyssey.'' Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984. ISBN 0292764693 | ||

| + | * Kaufman, Burton Ira, and Kaufman, Scott. ''The Presidency of James Earl Carter, Jr.'' Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006. ISBN 0700614710 | ||

| + | * Kucharsky, David. ''The Man from Plains: The Mind and Spirit of Jimmy Carter.'' Boston: G. K. Hall, 1977, 1976. ISBN 0816164703 | ||

| + | * Lance, Bert. ''The Truth of the Matter: My Life in and out of Politics.'' New York: Summit Books, 1991. ISBN 0671690272 | ||

| + | * Ribuffo, Leo P. "God and Jimmy Carter" in ''Transforming Faith: The Sacred and Secular in Modern American History,'' edited by Myles L. Bradbury, and James B. Gilbert, 141-59. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989. ISBN 0313257078 | ||

| + | * Ribuffo, Leo P. "'Malaise' revisited: Jimmy Carter and the crisis of confidence." in ''The Liberal Persuasion: Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and the Challenge of the American Past,'' edited by John Patrick Diggins, 164-185. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997. ISBN 0691048290 | ||

| + | * Rosenbaum, Herbert D. and Alexej Ugrinsky (eds.). ''The Presidency and Domestic Policies of Jimmy Carter.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994. ISBN 0313288453 | ||

| + | * Schram, Martin. ''Running for President, 1976: The Carter Campaign.'' New York: Stein and Day, 1977. ISBN 0812822455 | ||

| + | * Shoup, Laurence H. ''The Carter Presidency and Beyond: Power and Politics in the 1980's''. Ramparts Press, 1979. ISBN 0878670750 | ||

| + | * Strong, Robert. ''Working in the World: Jimmy Carter and the Making of American Foreign Policy.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000. ISBN 0807124451 | ||

| + | * White, Theodore Harold. ''America in Search of Itself: The Making of the President, 1956-1980.'' Warner Books; Reissue edition, 1988. ISBN 0446370983 | ||

| + | * Witcover, Jules. ''Marathon: The pursuit of the presidency, 1972-1976.'' New York: Viking Press, 1977. ISBN 0670454613 | ||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| − | *[ | + | All links retrieved December 2, 2023. |

| − | * State of the Union Addresses: | + | *[https://www.cartercenter.org// The Carter Center] |

| − | *[ | + | * [https://achievement.org/achiever/jimmy-carter/ Jimmy Carter] ''Academy of Achievement'' |

| − | + | *[https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/ Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum] | |

| − | + | *[https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/carter.asp Inaugural Address of Jimmy Carter] ''The Avalon Project''. | |

| − | *[ | + | * State of the Union Addresses: [https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/245063 1978], [https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/249816 1979], [https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/249681 1980], https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/250760 1981 (written message)] ''American Presidency Project'' |

| − | + | *[https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2002/carter/lecture/ Nobel lecture], Oslo, Norway, December 10, 2002, ''The Nobel Prize''. | |

| − | + | *[https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/jimmycartercrisisofconfidence.htm Energy and the National Goals - A Crisis of Confidence] July 15, 1979, ''American Rhetoric''. | |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.rediff.com/news/2000/mar/14onk.htm "The U.S. President was here"] about Carterpuri, a village in Haryana, India named after President Carter |

*[http://www.statecraft.org/chapter13.html Instruments of Statecraft: U.S. Guerrilla Warfare, Counterinsurgency, and Counterterrorism, 1940-1990 Chap. 3 The Carter Years] | *[http://www.statecraft.org/chapter13.html Instruments of Statecraft: U.S. Guerrilla Warfare, Counterinsurgency, and Counterterrorism, 1940-1990 Chap. 3 The Carter Years] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* {{gutenberg author| id=Jimmy+Carter | name=Jimmy Carter}} | * {{gutenberg author| id=Jimmy+Carter | name=Jimmy Carter}} | ||

* {{imdb name|id=0141699|name=Jimmy Carter}} | * {{imdb name|id=0141699|name=Jimmy Carter}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{Template:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates 2001-2025}} | |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Living people]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Politicians and reformers]] |

| + | [[Category:Nobel Peace Prize Winners]] | ||

{{credit|65433595}} | {{credit|65433595}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:54, 3 January 2024

| Term of office | January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981 |

| Preceded by | Gerald Ford |

| Succeeded by | Ronald Reagan |

| Date of birth | October 1, 1924 |

| Place of birth | Plains, Georgia |

| Spouse | Rosalynn Smith Carter (m. 1946; died 2023) |

| Political party | Democratic |

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. (born October 1, 1924) was the 39th President of the United States (1977–1981) and a Nobel Peace laureate. Previously, he was the Governor of Georgia (1971–1975). In 1976, Carter won the Democratic nomination as a dark horse candidate, and went on to defeat incumbent Gerald Ford in the close 1976 presidential election.

As President, his major accomplishments included the consolidation of numerous governmental agencies into the newly-formed Department of Energy, a cabinet level department. He enacted strong environmental legislation, deregulated the trucking, airline, rail, finance, communications, and oil industries, bolstered the Social Security system, and appointed record numbers of women and minorities to significant government and judicial posts. In foreign affairs, Carter's accomplishments included the Camp David Accords, the Panama Canal Treaties, the creation of full diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, and the negotiation of the SALT II Treaty. In addition, he championed human rights throughout the world as the center of his foreign policy.

During his term, however, the Iranian hostage crisis was a devastating blow to national prestige; Carter struggled for 444 days without success to release the hostages. A failed rescue attempt led to the resignation of his Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. The hostages were finally released the day Carter left office, 20 minutes after President Ronald Reagan's inauguration.

In the Cold War, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan marked the end of détente, and Carter boycotted the Moscow Olympics and began to rebuild American military power. He beat off a primary challenge from Senator Ted Kennedy but was unable to combat severe stagflation in the U.S. economy. The "Misery Index," his favored measure of economic well-being, rose 50 percent in four years. Carter feuded with the Democratic leaders who controlled Congress and was unable to reform the tax system or implement a national health plan.

After 1980, Carter assumed the role of elder statesman and international mediator, using his prestige as a former president to further a variety of causes. He founded the Carter Center, for example, as a forum for issues related to democracy and human rights. He has also traveled extensively to monitor elections, conduct peace negotiations, and coordinate relief efforts. In 2002, Carter won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in the areas of international conflicts, human rights, and economic and social development. Carter has continued his decades-long active involvement with the charity Habitat for Humanity, which builds houses for the needy.

Early Years

James Earl (Jimmy) Carter, Jr., the first President born in a hospital, was the oldest of four children of James Earl and Lillian Carter. He was born in the southwest Georgia town of Plains and grew up in nearby Archery, Georgia. Carter was a gifted student from an early age who always had a fondness for reading. By the time he attended Plains High School, he was also a star in basketball and football. Carter was greatly influenced by one of his high school teachers, Julia Coleman. Ms. Coleman, who was handicapped by polio, encouraged young Jimmy to read War and Peace. Carter claimed he was disappointed to find that there were no cowboys or Indians in the book. Carter mentioned his beloved teacher in his inaugural address as an example of someone who beat overwhelming odds.

Carter had three younger siblings, one brother and two sisters. His brother, Billy (1937–1988), would cause some political problems for him during his administration. One sister, Gloria (1926–1990), was famous for collecting and riding Harley-Davidson motorcycles. His other sister, Ruth (1929–1983), became a well-known Christian evangelist.

After graduating from high school, Jimmy Carter attended Georgia Southwestern College and the Georgia Institute of Technology. He received a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy in 1946. He married Rosalynn Carter later that year. At the Academy, Carter had been a gifted student finishing 59th out of a class of 820. Carter served on submarines in the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. He was later selected by Admiral Hyman G. Rickover for the United States Navy's fledgling nuclear submarine program, where he became a qualified command officer.[1] Carter loved the Navy, and had planned to make it his career. His ultimate goal was to become Chief of Naval Operations, but after the death of his father, Carter chose to resign his commission in 1953 when he took over the family's peanut farming business.

From a young age, Carter showed a deep commitment to Christianity, serving as a Sunday School teacher throughout his political career. Even as President, Carter prayed several times a day, and professed that Jesus Christ was the driving force in his life. Carter had been greatly influenced by a sermon he had heard as a young man, called, "If you were arrested for being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?" [2]

After World War II and during Carter's time in the Navy, he and Rosalynn started a family. They had three sons: John William, born in 1947; James Earl III, born in 1950; and Donnel Jeffrey, born in 1952. The couple also had a daughter, Amy Lynn, who was born in 1967.

The couple celebrated their 77th anniversary on July 7, 2023. On October 19, 2019, they became the longest-wed presidential couple, having overtaken George and Barbara Bush at 26,765 days. After Rosalynn's death on November 19, 2023, Carter released the following statement:

Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished. She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.[3]

Early Political Career

Georgia State Senate

Carter began his political career by serving on various local boards, governing such entities as the schools, hospital, and library, among others.

In 1962, Carter was elected to the Georgia state senate. He wrote about that experience, which followed the end of Georgia's County Unit System (per the Supreme Court case of Gray v. Sanders), in his book Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age. The election involved widespread corruption led by Joe Hurst, the sheriff of Quitman County (Examples of fraud included people voting in alphabetical order and dead people voting). It took a legal challenge on Carter's part for him to win the election. Carter was reelected in 1964 to serve a second two-year term.

Campaign for Governor

In 1966, at the end of his career as a state senator, he considered running for the United States House of Representatives. His Republican opponent dropped out and decided to run for Governor of Georgia. Carter did not want to see a Republican as the governor of his state and in turn dropped out of the race for United States Congress and joined the race to become governor. Carter lost the Democratic primary, but drew enough votes as a third place candidate to force the favorite, Ellis Arnall, into a run-off, setting off a chain of events which resulted in the election of Lester Maddox.

For the next four years, Carter returned to his peanut farming business and carefully planned for his next campaign for governor in 1970, making over 1,800 speeches throughout the state.

During his 1970 campaign, he ran an uphill populist campaign in the Democratic primary against former Governor Carl Sanders, labeling his opponent "Cufflinks Carl." Although Carter had never been a segregationist; he had refused to join the segregationist White Citizens' Council, prompting a boycott of his peanut warehouse, and he had been one of only two families which voted to admit African Americans to the Plains Baptist Church, he "said things the segregationists wanted to hear," according to historian E. Stanly Godbold.[4] Carter did not condemn Alabaman firebrand George Wallace, and chastised Sanders for not inviting Wallace to address the State Assembly during his tenure as Governor. Following his close victory over Sanders in the primary, he was elected governor over Republican Hal Suit.

Governor

After having run a campaign in which he promoted himself as a traditional southern conservative, Carter surprised the state and gained national attention by declaring in his inaugural speech that the time of racial segregation was over, and that racism had no place in the future of the state.[5] He was the first statewide office holder in the Deep South to say this in public (such sentiments would have signaled the end of the political career of politicians in the region less than 15 years earlier, as had been the fate of Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., who had testified before Congress in favor of the Voting Rights Act). Following this speech, Carter appointed many blacks to statewide boards and offices; he hung a photo of Martin Luther King, Jr. in the State House, a significant departure from the norm in the South.[6]

Carter bucked the tradition of the "New Deal Democrat" attempting a retrenchment, in favor of shrinking government. As an environmentalist, he opposed many public works projects. He particularly opposed the construction of large dams for construction's sake, opting to take a pragmatic approach based on a cost-benefits analysis.

While Governor, Carter made government more efficient by merging about 300 state agencies into 30 agencies. One of his aides recalled that Governor Carter "was right there with us, working just as hard, digging just as deep into every little problem. It was his program and he worked on it as hard as anybody, and the final product was distinctly his."[7] He also pushed reforms through the legislature, providing equal state aid to schools in the wealthy and poor areas of Georgia, set up community centers for mentally handicapped children, and increased educational programs for convicts. At Carter's urging, the legislature passed laws to protect the environment, preserve historic sites, and decrease secrecy in government. Carter took pride in a program he introduced for the appointment of judges and state government officials. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit, rather than political influence.

In 1972, as U.S. Senator George McGovern of South Dakota was marching toward the Democratic nomination for President, Carter called a news conference in Atlanta to warn that McGovern was unelectable. Carter criticized McGovern as being too liberal on both foreign and domestic policy. The remarks attracted little national attention, and after McGovern's huge loss in the general election, Carter's attitude was not held against him within the Democratic Party.

After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Georgia's death penalty law in 1972 in the Furman v. Georgia case, Carter signed new legislation to authorize the death penalty for murder, rape and other offenses and to implement trial procedures which would conform to the newly-announced constitutional requirements. The Supreme Court upheld the law in 1976.

In 1974, Carter was chairman of the Democratic National Committee's congressional and gubernatorial campaigns.

1976 Presidential Campaign