Columbia River

| Columbia River | |||

|---|---|---|---|

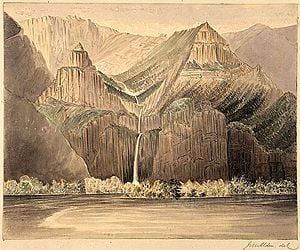

Columbia River near Revelstoke, British Columbia

| |||

| Countries | Canada, United States | ||

| States | Washington, Oregon | ||

| Provinces | British Columbia | ||

| Major cities | Revelstoke, British Columbia, Wenatchee, WA, Tri-Cities, WA, Portland, OR | ||

| Length | 1,243 miles (2,000 km) [1] | ||

| Watershed | 258,000 miles² (668,217 km²) | ||

| Discharge | mouth | ||

|  - average | 265,000 feet³/sec. (7,504 meters³/sec.) [2] | ||

|  - maximum | 1,240,000 feet³/sec. (35,113 meters³/sec.) | ||

|  - minimum | 12,100 feet³/sec. (343 meters³/sec.) | ||

| Source | Columbia Lake | ||

|  - location | British Columbia, Canada | ||

| ¬†-¬†coordinates | 50¬į13‚Ä≤N 115¬į51‚Ä≤W [3] | ||

|  - elevation | 2,650 feet (808 meters) [4] | ||

| Mouth | Pacific Ocean | ||

|  - coordinates | coord}}{{#coordinates:46|14|39|N|124|3|29|W|landmark | name=

}} [5] | |

|  - elevation | 0 feet (0 meters) | ||

| Major tributaries | |||

|  - left | Kootenay River, Pend Oreille River, Spokane River, Snake River, Deschutes River, Willamette River | ||

|  - right | Okanogan River, Yakima River, Cowlitz River | ||

The Columbia River is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. It stretches from the Canadian province of British Columbia through the U.S. state of Washington, forming much of the border between Washington and Oregon before emptying into the Pacific Ocean. The river is 1243 miles (2000 km) in length, with a drainage basin covering 258,000 square miles (670,000 km²). Measured by the volume of its flow, the Columbia is the largest river flowing into the Pacific from North America and is the fourth-largest river in the United States. It is the largest hydroelectric power producing river in North America with fourteen hydroelectric dams in the two nations it traverses.

The taming of the river for human use, and the industrial waste that resulted in some cases, have come into conflict with ecological conservation numerous times since non-Native settlement began in the area in the eighteenth century. Its "harnessing" included dredging for navigation by larger ships, nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons research and production, and the construction of dams for power generation, irrigation, navigation, and flood control.

The Columbia and its tributaries are home to numerous anadromous fish, which migrate between small fresh water tributaries of the river and the ocean. These fish‚ÄĒespecially the various species of salmon‚ÄĒhave been a vital part of the river's ecology and the local economy for thousands of years. This river is the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest; arguably the most significant environmental force in the region. A number of organizations are working toward its clean-up and attempting to restore ecological balance which was disrupted by unwise use.

Geography

The headwaters of the Columbia River are formed in Columbia Lake (elevation 2,690 feet (820 m), in the Canadian Rockies of southern British Columbia. Forty percent of the river's course, approximately 500 miles of its 1,240-mile stretch, lies in Canada, between its headwaters and the U.S. border.

The Pend Oreille River joins the Columbia about 2 miles north of the U.S.‚ÄďCanadian border. The Columbia enters eastern Washington flowing southwest. It marks the southern and eastern borders of the Colville Indian Reservation and the western border of the Spokane Indian Reservation before turning south and then southeasterly near the confluence with the Wenatchee River in central Washington. This C-shaped segment of the river is also known as the "Big Bend."

The river continues southeast, past the Gorge Amphitheatre and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, before meeting the Snake River in what is known as the Tri-Cities of Washington. The confluence of the Yakima, Snake, and Columbia rivers in the desert region of the southeastern part of the state, known as the Hanford Reach, is the only American stretch of the river that is free-flowing, unimpeded by dams and is not a tidal estuary. The Columbia makes a sharp bend to the west where it meets the state of Oregon. The river forms the border between Washington and Oregon for the final 309 miles of its journey.

The Columbia is the only river to pass through the Cascade Mountains, which it does between The Dalles, Oregon, and Portland, Oregon, forming the Columbia River Gorge. The gorge is known for its strong, steady winds, its scenic beauty, and as an important transportation link.

The river continues west with one small north-northwesterly-directed stretch near Portland, Vancouver, Washington, and the river's confluence with the Willamette River. On this sharp bend, the river’s flow slows considerably, and it drops the sediment that might otherwise form a river delta. The river empties into the Pacific Ocean near Astoria, Oregon; the Columbia River sandbar is widely considered one of the most difficult to navigate.

Major tributaries are the Kootenay, Snake, Pend Oreille, Spokane, Okanogan, Yakima, Cowlitz, and Willamette rivers. High flows occur in late spring and early summer, when snow melts in the mountainous watershed. Low flows occur in autumn and winter, causing water shortages at the river's hydroelectric plants.[6]

Columbia River Gorge

The Columbia River Gorge is a canyon of the Columbia River. Up to 4,000 feet (1,300 m) deep, the canyon stretches for over 80 miles (130 km) as the river winds through the Cascade Range forming the boundary between Washington to the north and Oregon to the south.

The gorge is the only water connection between the Columbia River Plateau and the Pacific Ocean. Extending roughly from the confluence of the Columbia with the Deschutes River down to eastern reaches of the Portland metropolitan area, the gorge furnishes the only navigable route through the Cascades.

In addition to its natural beauty, the gorge also provides a critical transportation corridor. Natives would travel through the Gorge to trade at Celilo falls, both along the river and over Lolo Pass on the north side of Mount Hood; Americans followed similar routes when settling the region, and later established steamboat lines and railroads through the gorge. In 1805, the route was used by the Lewis and Clark Expedition to reach the Pacific. Shipping was greatly simplified after Bonneville Dam and The Dalles Dam submerged the gorge's major rapids. The Columbia River Highway, built in the early twentieth century, was the first major paved highway in the Pacific Northwest, and remains famous for its scenic beauty.

The gorge also contains the greatest concentration of waterfalls in the region, with over 77 waterfalls on the Oregon side of the gorge alone. Many are along the Historic Columbia River Highway, including the notable Multnomah Falls, which claims a drop of 620 feet (188 m). In November 1986, Congress recognized the unique beauty of the gorge by making it the first U.S. National Scenic Area and establishing the Columbia River Gorge Commission as part of an interstate compact.

Drainage basin

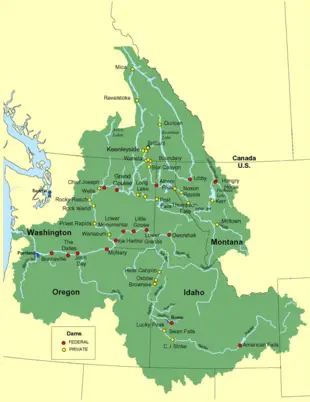

The Columbia River flows 1,243 miles (2,000 km) from its headwaters to the Pacific and drains an area of about 260,000 square miles (670,000 km²).[7] Its drainage basin includes territory in seven U.S. states and one Canadian province: Most of the state of Idaho, large portions of British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington, and small portions of Montana, Nevada, Wyoming, and Utah. Roughly 85 percent of the drainage basin and 745 miles (1,200 km) of the river's length are in the United States.[8]

With an average annual flow of about 265 thousand cubic feet per second, the Columbia is the largest river by volume flowing into the Pacific from North America and is the fourth-largest by volume in the United States. Ranked by size of drainage basin, it is sixth-largest in the U.S., while its length earns it the rank of twelfth-largest.[9] The Columbia's highest recorded flow, measured at The Dalles, Oregon, was 1,240 thousand cubic feet per second in June 1894.[10]

Plant and animal life

Sagebrush and bunchgrasses dominate native vegetation at the lower elevations of the river's interior basin, which is mainly of the shrub-steppe variety. The original shrub-steppe vegetation has in large part‚ÄĒover 50 percent‚ÄĒbeen destroyed by farming and grazing.

As elevation increases, ponderosa pine and then to fir, larch, and other pines replace the shrub. Willow and black cottonwood dominate the terrain along watercourses. Forests of Douglas fir with hemlock and western red cedar prevail in upland areas west of the Cascade Mountains.

The area was once abundant in animal life, especially great runs of salmon and steelhead trout. Plentiful were bear, beaver, deer, elk, and bighorn sheep. Birdlife included eagles, falcons, hawks, and ospreys. However, as the area became more densely populated, the region's ability to sustain large numbers of wildlife has been hindered, especially for the beaver and salmon populations. The bald eagle has been listed as threatened, while the peregrine falcon is considered an endangered species in the region.[11]

Geology

Volcanic activity in the region has been traced to 40 million years ago, in the Eocene era, forming much of the landscape traversed by the Columbia. In the Pleistocene era (the last ice age, two million to 700,000 years ago), the river broke through the Cascade Range, forming the 100-mile-long and 3,000-foot-deep Columbia River Gorge.[8]

Missoula floods

During the last Ice Age, a finger of the Cordilleran ice sheet crept southward into the Idaho Panhandle, blocking the Clark Fork River and creating Glacial Lake Missoula. As the waters rose behind this 2,000-foot ice dam, they flooded the valleys of western Montana. At its greatest extent, Glacial Lake Missoula stretched eastward a distance of some 200 miles, essentially creating an inland sea.

Periodically, the ice dam would fail. These failures were often catastrophic, resulting in a large flood of ice and dirt-filled water that would rush down the Columbia River drainage, across what is now northern Idaho and eastern and central Washington, through the Columbia River Gorge, back up into Oregon's Willamette Valley, and finally pour into the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the Columbia River.

The glacial lake, at its maximum height and extent, contained more than 500 cubic miles of water. When Glacial Lake Missoula burst through the ice dam and exploded downstream, it did so at a rate 10 times the combined flow of all the rivers of the world. This towering mass of water and ice literally shook the ground as it thundered towards the Pacific Ocean, stripping away thick soils and cutting deep canyons in the underlying bedrock. With flood waters roaring across the landscape at speeds approaching 65 miles per hour, the lake would have drained in as little as 48 hours.

But the Cordilleran ice sheet continued moving south and blocking the Clark Fork River again and again, creating other Glacial Lake Missoulas. Over thousands of years, the lake filling, dam failure, and flooding were repeated dozens of times, leaving a lasting mark on the landscape of the Northwest. Many of the distinguishing features of the Ice Age Floods remain throughout the region today.

The floods' periodic inundation of the lower Columbia River Plateau deposited rich lake sediments, establishing the fertility that supports extensive agriculture in the modern era. They also formed many unusual geological features, such as the channeled scablands of eastern Washington.

A mountain on the north side of the Columbia River Gorge is thought to be the result of the Cascadia earthquake in 1700, in an event known as the Bonneville Slide. The resulting land bridge blocked the river until rising waters tunneled through and finally washed away the sediment. In 1980, the eruption of Mount St. Helens deposited large amounts of sediment in the lower Columbia, temporarily reducing the depth of the shipping channel by 25 feet (7.6 m).

History

Indigenous peoples

Humans have inhabited the Columbia River Basin for more than 15,000 years, with a transition to a sedentary lifestyle based mainly on salmon beginning about 3,500 years ago.[12]

In 1962, archaeologists found evidence of human activity dating back 11,230 years at the Marmes Rockshelter, near the confluence of the Palouse and Snake rivers in eastern Washington. In 1996, the skeletal remains of a 9,000 year old prehistoric man (dubbed Kennewick Man) were found near Kennewick, Washington. The discovery rekindled debate in the scientific community over the origins of human habitation in North America and sparked a protracted controversy over whether the scientific or Native American community was entitled to possess and/or study the remains.[13]

Several tribes and First Nations have a historical and continuing presence on the Columbia. The Sinixt or Lakes people lived on the lower stretch of the Canadian portion, the Secwepemc on the upper; the Colville, Spokane, Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs live along the U.S. stretch. Along the upper Snake River and Salmon River, the Shoshone Bannock Tribes are present. Near the lower Columbia River, the Cowlitz and Chinook tribes, which are not federally recognized, are present. The Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Warm Springs tribes all have treaty fishing rights along the Columbia and its tributaries.

Perhaps a century before Europeans began to explore the Pacific Northwest, the Bonneville Slide created a land bridge in the Columbia Gorge, known to natives as the Bridge of the Gods. The bridge was described as the result a battle between gods, represented by Mount Adams and Mount Hood, vying for the affection of a goddess, represented by Mount St. Helens. The bridge permitted increased interaction and trade between tribes on the north and south sides of the river until it was finally washed away.

The Cascades Rapids of the Columbia River Gorge, and Kettle Falls and Priest Rapids in eastern Washington, were important fishing and trading sites submerged by the construction of dams. The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, a coalition of various tribes, adopted a constitution and incorporated after the 1938 completion of the Bonneville Dam flooded Cascades Rapids.[14]

For 11,000 years, Celilo Falls was the most significant economic and cultural hub for native peoples on the Columbia. It was located east of the modern city of The Dalles. An estimated 15 to 20 million salmon passed through the falls every year, making it one of the greatest fishing sites in North America.[15] The falls were strategically located at the border between Chinookan and Sahaptian speaking peoples and served as the center of an extensive trading network across the Pacific Plateau.[16] It was the oldest continuously inhabited community on the North American continent until 1957, when it was submerged by the construction of The Dalles Dam and the native fishing community was displaced. The affected tribes received a $26.8 million settlement for the loss of Celilo and other fishing sites submerged by the Dalles Dam.[17] The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs used part of its $4 million settlement to establish the Kah-Nee-Tah resort south of Mount Hood.[14]

Exploration and settlement

In 1775, Bruno de Heceta became the first European to detect the mouth of the Columbia River. On the advice of his officers, he did not explore it, as he was short-staffed and the current was strong. Considering it a bay, he called it Ensenada de Asunción. Later Spanish maps based on his discovery showed a river, labeled Rio de San Roque.

British fur trader Captain John Meares sought the river based on Heceta's reports, in 1788. He misread the currents, and concluded that the river did not in fact exist. British Royal Navy commander George Vancouver sailed past the mouth in April 1792, but did not explore it, assuming Meares' reports were correct.

On May 11, 1792, the American captain Robert Gray managed to sail into the Columbia, becoming the first explorer to enter it. Gray had traveled to the Pacific Northwest to trade for furs in a privately owned vessel named Columbia Rediviva; he named the river after the ship. Gray spent nine days trading near the mouth of the Columbia, then left without having gone beyond 13 miles (21 km) upstream. Vancouver soon learned that Gray claimed to have found a navigable river, and went to investigate for himself. In October 1792, Vancouver sent Lieutenant William Robert Broughton, his second-in-command, up the river. Broughton sailed up for some miles, then continued in small boats. He got as far as the Columbia River Gorge, about 100 miles (160 km) upstream, sighting and naming Mount Hood. He also formally claimed the river, its watershed and the nearby coast for Britain. Gray's discovery of the Columbia was used by the United States to support their claim to the Oregon Country, which was also claimed by Russia, Great Britain, Spain, and other nations.[18]

American explorers Lewis and Clark, who charted the vast, unmapped lands west of the Missouri River, traveled down the Columbia, on the last stretch of their 1805 expedition. They explored as far upstream as Bateman Island, near present-day Tri-Cities, Washington. Their journey concluded at the river's mouth.

Canadian explorer David Thompson, of the North West Company, spent the winter of 1807‚Äď08 at Kootenae House near the source of the Columbia at present day Invermere, British Columbia. In 1811, he traveled down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean, becoming the first European-American to travel the entire length of the river.

In 1825, on behalf of the Hudson's Bay Company, Dr. John McLoughlin established Fort Vancouver, nor the present-day city of Vancouver, Washington, on the banks of the Columbia as a fur trading headquarters in the company's Columbia District. The fort was by far the largest European settlement in the northwest at the time. Every year ships came from London via the Pacific to deliver supplies and trade goods in exchange for furs. The fort became the last stop on the Oregon Trail to buy supplies and land before settleers began their homestead. Because of its access to the Columbia River, Fort Vancouver’s influence reached from Alaska to California and from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands.

The United States and Great Britain agreed, in 1818, to settle the Oregon Country jointly. Americans generally settled south of the river, while British fur traders generally settled to the north. The Columbia was considered a possible border in the boundary dispute that ensued, but ultimately the Oregon Treaty of 1846 established the boundary at the 49th parallel. The river later came to define most of the border between the U.S. territories of Oregon and Washington, which became states in 1857 and 1889, respectively.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the difficulty of navigating the Columbia was seen as an impediment to the economic development of the Inland Empire region east of the Cascades.[19] The dredging and dam building that followed would permanently alter the river, disrupting its natural flow, but also providing electricity, irrigation, navigability, and other benefits to the region.

Development

Explorers Robert Gray and George Vancouver, who explored the river in 1792, proved that it was possible to cross the Columbia Bar. But the challenges associated with that feat remain today; even with modern engineering alterations to the mouth of the river, the strong currents and shifting sandbar make it dangerous to pass between the river and the Pacific Ocean.

The use of steamboats along the river, beginning in 1850, contributed to the rapid settlement and economic development of the region. Steamboats, initially powered by burning wood, carried both passengers and freight throughout the region for many years. In the 1880s, railroads maintained by companies such as the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company and the Shaver Transportation Company began to supplement steamboat operations as the major transportation links along the river.

As early as 1881, industrialists proposed altering the natural channel of the Columbia to improve navigation.[20] Changes to the river over the years have included the construction of jetties at the river's mouth, dredging, and the construction of canals and navigation locks. Today, ocean freighters can travel upriver as far as Portland and Vancouver, and barges can reach as far inland as Lewiston, Idaho.[8]

Dams

The dams in the United States are owned by the Federal Government (Army Corps of Engineers or Bureau of Reclamation), Public Utility Districts, and private power companies.

Hydroelectricity

The Columbia's extreme elevation drop over a relatively short distance (2,700 feet in 1,232 miles, or 822 m in 1,982 km) gives it tremendous potential for hydroelectricity generation. It was estimated in the 1960s‚Äď70s that the Columbia represented 1/5 of the total hydroelectric capacity on Earth (although these estimates may no longer be accurate.) The Columbia drops 2.16 feet per mile (0.41 meters per kilometer), as compared with the Mississippi which drops less than 0.66 feet per mile (0.13 meters per kilometer).

Today, the mainstream of the Columbia River has 14 dams (three in Canada, 11 in the United States.) Four mainstream dams and four lower Snake River dams have locks to allow ship and barge passage. Numerous Columbia River tributaries have dams for hydroelectric and/or irrigation purposes. While hydroelectricity accounts for only 6.5 percent of energy in the United States, the Columbia and its tributaries provide approximately 60 percent of the hydroelectric power on the west coast.[21] The largest of the 150 hydroelectric projects, the Columbia's Grand Coulee and the Chief Joseph Dams, both in Washington state, are also the largest in the U.S.; the Grand Coulee is the third largest in the world.

Irrigation

The dams also make it possible for ships to navigate the river, as well as provide irrigation. Grand Coulee Dam provides water for the Columbia Basin Project, one of the most extensive irrigation projects in the western United States. The project provides water to over 500,000 acres (2,000 km²) of fertile but arid lands in central Washington State. Water from the project has transformed the region from a wasteland barely able to produce subsistence levels of dry-land wheat crops to a major agricultural center. Important crops include apples, potatoes, alfalfa, wheat, corn (maize), barley, hops, beans, and sugar beets.

Disadvantages

Although dams provide benefits like clean, renewable energy, they drastically alter the landscape and ecosystem of the river. At one time the Columbia was one of the top salmon-producing river systems in the world. Previously active fishing sites, such as Celilo Falls (covered by the river when The Dalles Dam was built) in the eastern Columbia River Gorge, have exhibited a sharp decline in fishing along the Columbia in the last century. The presence of dams, coupled with over-fishing, has played a major role in the reduction of salmon populations.

Fish ladders have been installed at some dam sites to assist the fish in the journey to spawning waters. Grand Coulee Dam has no fish ladders and completely blocks fish migration to the upper half of the Columbia River system. Downriver of Grand Coulee, each dam’s reservoir is closely regulated by the Bonneville Power Administration, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and various Washington Public Utility Districts to ensure flow, flood control, and power generation objectives are met. Increasingly, hydro-power operations are required to meet standards under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and other agreements to manage operations to minimize impacts on salmon and other fish, and some conservation and fishing groups support removing four dams on the lower Snake River, the largest tributary of the Columbia.

Environmental concerns

Impact of dams on fish migration

The Columbia supports several species of anadromous fish that migrate between the Pacific Ocean and fresh water tributaries of the river. Coho and Chinook (also called King) salmon and Steelhead, all of the genus Oncorhynchus, are ocean fish that migrate up the rivers at the end of their life cycles to spawn. White sturgeon, which take 25 years to grow to full size, typically migrate between the ocean and the upstream habitat several times during their lives.

Dams interrupt the migration of anadromous fish. Salmon and steelhead return to the streams in which they were born to spawn; where dams prevent their return, entire populations of salmon die. Some of the Columbia and Snake River dams employ fish ladders, which are effective to varying degrees at allowing these fish to travel upstream. Another problem exists for the juvenile salmon headed downstream to the ocean. Previously, this journey would have taken two to three weeks. With river currents slowed by the dams, and the Columbia converted from wild river to a series of slackwater pools, the journey can take several months, which increases the mortality rate. In some cases, the Army Corps of Engineers transports juvenile fish downstream by truck or river barge. The Grand Coulee Dam and several dams on the Columbia's tributaries entirely block migration, and there are no migrating fish on the river above these dams.

In 1994, United States Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt first proposed the removal of several Pacific Northwest dams because of their impact on salmon spawning. In the same year, the Northwest Power Planning Council approved a plan that provided more water for fish and less for electricity, irrigation, and transportation. Environmental advocates have called for the removal of certain dams in the Columbia system in the years since. Of the 227 major dams in the Columbia River Basin, the four Washington dams on the lower Snake River are often identified for removal, notably in an ongoing lawsuit concerning a Bush administration plan for salmon recovery.[22]

Hanford Site

In southeastern Washington, a 50-mile (80 km) stretch of the river passes through the Hanford Site, established in 1943, as part of the Manhattan Project. The site served as a plutonium production complex, with nine nuclear reactors and related facilities located on the banks of the river. From 1944 to 1971, pump systems drew cooling water from the river and, after treating this water for use by the reactors, returned it to the river. Before being released back into the river, the used water was held in large tanks known as retention basins for up to six hours. Longer-lived isotopes were not affected by this retention, and several terabecquerels entered the river every day. By 1957, the eight plutonium production reactors at Hanford dumped a daily average of 50,000 curies of radioactive material into the Columbia. Hanford is the most contaminated nuclear site in the western world, whose radioactive and toxic wastes pose serious health and environmental threats.[23]

Hanford's nuclear reactors were decommissioned at the end of the Cold War, and the Hanford site is now the focus of the world’s largest environmental cleanup, managed by the Department of Energy under the oversight of the Washington Department of Ecology and the Environmental Protection Agency.[24]

Pollution

In addition to concerns about nuclear waste, numerous other pollutants are found in the river. These include chemical pesticides, bacteria, arsenic, dioxins, and polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB).[25]

Studies have also found significant levels of toxins in fish and the waters they inhabit within the basin. Accumulation of toxins in fish threatens the survival of fish species, and human consumption of these fish can lead to health problems. Water quality is also an important factor in the survival of other wildlife and plants that grow in the Columbia River Basin. The states, Indian tribes, and federal government are all engaged in efforts to restore and improve the water, land, and air quality of the Columbia River Basin and have committed to work together to enhance and accomplish critical ecosystem restoration efforts. A number of cleanup efforts are currently underway, including Superfund projects at Portland Harbor, Hanford, and Lake Roosevelt.[26]

Culture

<left>

| Roll on, Columbia, roll on, roll on, Columbia, roll on Your power is turning our darkness to dawn Roll on, Columbia, roll on. ‚ÄĒRoll on Columbia by Woody Guthrie, written under commission of the Bonneville Power Administration |

With the importance of the Columbia to the Pacific Northwest, it has made its way into the culture of the area and the nation. Celilo Falls, in particular, was an important economic and cultural hub of western North America for as long as 10,000 years.

Kitesurfing and Windsurfing have become popular sports, particularly in Hood River, considered by many as the world capital of windsurfing.

Several Indian tribes have a historical and continuing presence on the Columbia River, most notably the Sinixt or Lakes people in Canada and in the U.S. the Colvile, Spokane, Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs Tribes. In the upper Snake River and Salmon River basin the Shoshone Bannock Tribes are present. In the Lower Columbia River, the Cowlitz and Chinook Tribes are present, but these tribes are not federally recognized. The Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Warm Springs Tribes all have treaty fishing rights in the Columbia River and tributaries.

Major tributaries

| Tributary | Average discharge: | |

|---|---|---|

| cu ft/s | m³/s | |

| Snake River | 56,900 | 1,611 |

| Willamette River | 35,660 | 1,010 |

| Kootenay River (Kootenai) | 30,650 | 867 |

| Pend Oreille River | 27,820 | 788 |

| Cowlitz River | 9,200 | 261 |

| Spokane River | 6,700 | 190 |

| Deschutes River | 6,000 | 170 |

| Lewis River | 4,800 | 136 |

| Yakima River | 3,540 | 100 |

| Wenatchee River | 3,220 | 91 |

| Okanogan River | 3,050 | 86 |

| Kettle River | 2,930 | 83 |

| Sandy River | 2,260 | 64 |

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Columbia Riverkeeper. Protecting the Columbia River. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ J.C. Kammerer, Largest Rivers in the United States, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Google Earth coordinates for Columbia Lake. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Google Earth elevation for Columbia Lake. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Board on Geographic Names. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Encyclop√¶dia Britannica, Columbia River, Encyclop√¶dia Britannica Online.

- ‚ÜĎ Encarta Online Encyclopedia, Columbia (river, North America), Microsoft. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bill Lang, Columbia River. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ J.C. Kammerer, Largest Rivers in the United States, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Northwest Power and Conservation Council, Columbia River History: Hydropower. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Encyclop√¶dia Britannica, Columbia River, Encyclop√¶dia Britannica Online.

- ‚ÜĎ National Research Council (U.S.), Managing The Columbia River: Instream Flows, Water Withdrawals, and Salmon Survival (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2004, ISBN 0309091551).

- ‚ÜĎ Michael D. Lemonick, Andrea Dorfman, and Dan Cray, Who Were The First Americans? Time Magazine. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ 14.0 14.1 Oregon Public Broadcasting, The Oregon Story. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ George Rohrbacher, Talk of the Past: The salmon fisheries of Celilo Falls, Common-place The Interactive Journal of Early American Life, Inc. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ James P. Ronda, Lewis & Clark Among the Indians (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1984, ISBN 0803289901).

- ‚ÜĎ William Dietrich, Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995, ISBN 067179650X).

- ‚ÜĎ Melvin Clay Jacobs, Winning Oregon: A Study of an Expansionist Movement (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers).

- ‚ÜĎ Lee B. Reeder, Open the Columbia to the Sea, Center for Columbia River History. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Edward Lloyd Affleck, A Century of Paddlewheelers in the Pacific Northwest, the Yukon and Alaska (Vancouver, B.C.: Alexander Nicolls Press, 2000, ISBN 9780920034088).

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Electric Power Annual, Energy Information Administration. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Michael Milstein, Judge rips latest plan to help salmon, The Oregonian. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility, Hanford History‚ÄĒHow did we get where we are? Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. Department of Energy, Hanford Site: Hanford Overview. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Ben Jacklet, July 24, 2001, "Activist Plans an Epic Swim," The Portland Tribune, Portland, OR.

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Columbia River Basin: A National Priority. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dietrich, William. 1995. Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 067179650X.

- Jackson, Tom. 2004. The Columbia River. Milwaukee, Wis: Gareth Stevens Pub. ISBN 0836837541.

- Lashnits, Tom. 2004. Columbia River. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791077284.

- Lewis, Meriwether, William Clark, Nicholas Biddle, and Paul Allen. 1966. The Expedition of Lewis and Clark. March of America facsimile series, no. 56. Ann Arbor [Mich.]: University Microfilms.

External links

All links retrieved January 7, 2024.

- Tollman and Canaris Photographs. University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.