Snake River

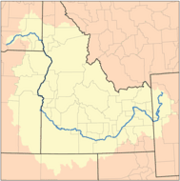

| Snake River | |

| River | |

Perrine Bridge spanning the Snake River Canyon at Twin Falls, Idaho

| |

| Country | |

|---|---|

| States | |

| Tributaries | |

|  - left | Salt River, Portneuf River, Owyhee River, Malheur River, Powder River, Grande Ronde River |

|  - right | Henrys Fork, Boise River, Salmon River, Clearwater River, Palouse River |

| Cities | Idaho Falls, Idaho, Twin Falls, Idaho, Lewiston, Idaho, Tri-Cities, Washington |

| Source | Rocky Mountains |

|  - location | Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming |

|  - elevation | 8,927 feet (2,721 meters) [1] |

| Mouth | Columbia River |

|  - location | Tri-Cities, Washington |

|  - elevation | 358 feet (109 meters) [2] |

| Length | 1,040 miles (1,674 km) [3] |

| Basin | 108,000 miles² (280,000 km²) [3] |

| Discharge | mouth |

|  - average | 56,900 feet³/sec. (1,610 meters³/sec.) [3] |

The Snake River is the largest tributary of the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. One of the most important rivers in the region, it rises in the mountains of the Continental Divide near the southeastern corner of Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, and flows through Idaho and Oregon before finally emptying into the Columbia River in Washington state.

Many dams have been built on the 1040 mile (1670 km) Snake River and its tributaries, mainly for purposes of providing irrigation water and hydroelectric power, ranging in size from small diversion dams to major high dams. While the many dams have transformed the region's economy, they have also had an adverse environmental effect on wildlife, most notably on wild salmon migrations. Since the 1990s, some conservation organizations and fishermen are seeking to restore the lower Snake River and its fish population by removing four federally-owned dams on the lower Snake River.

The lower section of the river flows through Hells Canyon Wilderness, the deepest river gorge in North America. Nearly 70 miles of this section is designated a National Wild and Scenic River. The purpose of this designation is to balance river development with permanent protection for the country's most outstanding free-flowing rivers. The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act is notable for safeguarding the special character of these rivers, while also recognizing the potential for appropriate use and development.

History

Name

The Snake River follows a serpentine course between Yellowstone National Park and the Columbia River. However, its name comes not from its shape, but from a local Native American tribe, the Shoshone, who lived along the river's shoreline in present-day southeastern Idaho.

The Shoshone marked their territory with sticks that showed an image of a snake. They also made an S-shaped sign with their hands to mimic swimming salmon, and used this as a sign of friendly greeting as well as to identify themselves as "the people who live near the river with many fish." It is believed that the first white explorers to the area misinterpreted the hand-sign as that of a "snake" and gave the name to the river that flowed through the tribe's traditional land.

Variant names of the river have included: Great Snake River, Lewis Fork, Lewis River, Mad River, Saptin River, Shoshone River, and Yam-pah-pa.

Early inhabitants

People have been living along the Snake River for at least 11,000 years. Daniel S. Meatte divides the prehistory of the western Snake River Basin into three main phases or "adaptive systems." The first he calls "Broad Spectrum Foraging," dating from 11,500 to 4,200 years before present. During this period, people drew upon a wide variety of food resources. The second period, "Semisedentary Foraging," dates from 4,200-250 years before present and is distinctive for an increased reliance upon fish, especially salmon, as well as food preservation and storage. The third phase, from 250 to 100 years before present, he calls "Equestrian Foragers." This period is characterized by large, horse-mounted tribes that spent long amounts of time away from their local foraging-range, hunting bison.[4]

In the eastern Snake River Plain there is some evidence of Clovis, Folsom, and Plano cultures dating back over 10,000 years ago. By the protohistoric and historic era, the eastern Snake River Plain was dominated by Shoshone and other "Plateau" culture tribes.[5]

Early fur traders and explorers noted regional trading centers, and archaeological evidence has shown some to be of considerable antiquity. One such trading center in the Weiser, Idaho, area existed as early as 4,500 years ago. The Fremont culture may have contributed to the historic Shoshones, but it is not well understood. Another poorly understood early cultural hearth is called the Midvale Complex.

The introduction of the horse to the Snake River Plain, around 1700, helped in establishing the Shoshone and Northern Paiute cultures.[4]

On the Snake River in southeastern Washington, there are several ancient sites. One of the oldest and most well-known is called the Marmes Rockshelter, which was used from over 11,000 years ago to relatively recent times. The Marmes Rockshelter was flooded in 1968, by Lake Herbert G. West, the Lower Monumental Dam's reservoir.[6]

Other cultures of the Snake River's basin's protohistoric and historic periods include the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Walla Walla, Palus, Bannock, and many others.

Exploration

The Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806 was the first major U.S. exploration of the lower portion of the Snake River. Later exploratory expeditions, which explored much of the length of the Snake, included the Astor Expedition of 1810-1812, John C. Frémont in 1832, and Benjamin Bonneville in 1833-1834. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Oregon Trail had been established, generally following much of the Snake River.

Geography

Basin overview

Snake River's drainage basin includes a diversity of landscapes. Its upper reaches lie in the Rocky Mountains. In southern Idaho the river flows through the broad Snake River Plain. Along the Idaho-Oregon border, the river flows through Hells Canyon, part of a larger physiographic region called the Columbia River Plateau. Through this, the Snake River flows through Washington to its confluence with the Columbia River. Parts of the river's basin lie within the Basin and Range province, though it is itself a physiographic section of the Columbia Plateau province, which in turn is part of the larger Intermontane Plateaus physiographic division.

The Snake is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, with a mean discharge of 50,000 cubic feet per second (1,400 m³/s),[7] or 56,900 cubic feet per second (1,610 m³/s) according to the USGS, the 12th largest in the United States.[3]

Geology

For much of its course, the Snake River flows through the Snake River Plain, a physiographic province extending from eastern Oregon through southern Idaho into northwest Wyoming. Much of this plain is high desert and semi-desert at elevations averaging around 5,000 feet (1,500 m). Many of the rivers in this region have cut deep and meandering canyons. West of the city of Twin Falls, the plain is mainly covered with stream and lake sediments.

During the Miocene, lava dams created Lake Idaho, which covered a large portion of the Snake River Plain between Twin Falls and Hells Canyon. This large lake expanded and contracted several times before finally receding in the early Pleistocene. In more recent geologic time, about 14,500 years ago, glacial Lake Bonneville spilled catastrophically into the Snake River Plain. The flood carved deep into the land along the Snake River, leaving deposits of gravel, sand, and boulders, as well as a scabland topography in places. Results of this flood include the falls and rapids from Twin Falls and Shoshone Falls to Crane Falls and Swan Falls, as well as the many "potholes" areas.[8]

The Snake River Aquifer, one of the most productive aquifers in the world, underlies an area of about 10,000 square miles (26,000 km²) in the Snake River Plain. Differences in elevation and rock permeability result in many dramatic springs, some of which are artesian. The groundwater comes from the Snake River itself as well as other streams in the region. Some streams on the northern side of the Snake River Plain, such as the Lost River are completely absorbed into the ground, recharging the aquifer and emerging as springs that flow into the Snake River in the western part of the plain. The hydraulic conductivity of the basalt rocks that make up the aquifer is very high. In places water exits the Snake and Lost rivers into ground conduits at rates of nearly .[8] Due to stream modifications and large-scale irrigation, most of the water that once recharged the aquifer directly now does so in the form of irrigation water drainage.[9]

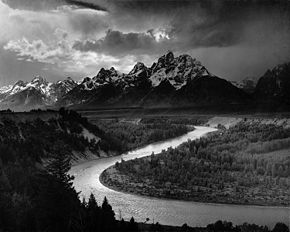

Upper course

The Snake originates near the Continental Divide in Yellowstone National Park in northwest Wyoming and flows south into Jackson Lake in Grand Teton National Park, then south through Jackson Hole and past the town of Jackson, Wyoming. The river then flows west through Wyoming's Snake River Canyon and exits Wyoming at Alpine Junction, where it enters Idaho at the Palisades Reservoir.

Below the Palisades Reservoir, the Snake River flows northwest through Swan Valley to its confluence with Henrys Fork near the town of Rigby, Idaho. The region around the confluence is a large inland delta. Above the juncture, the Snake River is locally called the South Fork of the Snake River, since Henrys Fork is sometimes called the North Fork of the Snake River.

The Snake River then swings south and west in an arc across southern Idaho, following the Snake River Plain. It passes through the city of Idaho Falls and by Blackfoot in a region of irrigated agriculture. North of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation the river is impounded by the American Falls Dam. The dam and reservoir are part of the Minidoka Irrigation Project managed by the United States Bureau of Reclamation. The Portneuf River joins the Snake at the reservoir. Downriver from the dam is Massacre Rocks State Park, a site on the path of the old Oregon Trail.

After receiving the waters of Raft River, the Snake River enters another reservoir, Lake Walcott, impounded by Minidoka Dam, run by the Bureau of Reclamation mainly for irrigation purposes. Another dam, Milner Dam and its reservoir, Milner Reservoir, lie just downriver from Minidoka Dam. Below that is the city of Twin Falls, after which the river flows into Idaho's Snake River Canyon over Shoshone Falls and under the Perrine Bridge.

Lower course

After exiting the Snake River Canyon, the Snake receives the waters of more tributaries, the Bruneau River and the Malad River. After passing the Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, the Snake flows toward Boise and the Idaho-Oregon border. After receiving numerous tributaries such as the Boise River, Owyhee River, Malheur River, Payette River, Weiser River, and Powder River, the Snake enters Hells Canyon.

In Hells Canyon, the Snake River is impounded by three dams, Brownlee Dam, Oxbow Dam, and Hells Canyon Dam (which completely blocks the migration of anadromous fish[10]), after which the river is designated a National Wild and Scenic River as is flows through Hells Canyon Wilderness. In this section of the river, the Salmon River, one of the largest tributaries of the Snake, joins. Just across the Washington state line, another large tributary, the Grande Ronde River joins the Snake.

As the Snake flows north out of Hells Canyon, it passes the cities of Lewiston, Idaho and Clarkston, Washington, where it receives the Clearwater River. From there the Snake River swings north, then south, through southeast Washington's Palouse region, before joining the Columbia River near the Tri-Cities. In this final river reach there are four large dams, Lower Granite Lock and Dam, Little Goose Lock and Dam, Lower Monumental Lock and Dam, and Ice Harbor Lock and Dam. These dams, built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers serve as hydroelectric power sources as well as ensuring barge traffic navigation to Lewiston, Idaho.

River modifications

Dams

Many dams have been built on the Snake River and its tributaries, mainly for purposes of providing irrigation water and hydroelectric power, ranging in size from small diversion dams to major high dams.

Large dams include four on the lower Snake, in Washington, built and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose, and Lower Granite. These dams were built between 1962 and 1975 for hydroelectric power and navigation. They are equipped with locks, making the river as far as Lewiston an extension of the Columbia River's barge navigation system.[11] The four dams were modified in the 1980s, to better accommodate fish passage.[12]

Upriver, in the Hells Canyon region, there are three large hydroelectric dams, operated by Idaho Power, a private utility company. Collectively named the Hells Canyon Project, the three dams are, in upriver order: Hells Canyon Dam, Oxbow Dam, and Brownlee Dam. Not having fish ladders, they are the first total barrier to upriver fish migration.

In southwestern Idaho there are several large dams. Swan Falls Dam, built in 1901, was the first hydroelectric dam on the Snake as well as the first total barrier to upriver fish migration. It was rebuilt in the 1990s by Idaho Power. Upriver from Swan Falls is another hydroelectric dam operated by Idaho Power, the C. J. Strike Dam, built in 1952. This dam also serves irrigation purposes. Continuing upriver, Idaho Power operates a set of three hydroelectric dam projects collectively called the Mid-Snake Projects, all built in the 1940s and 1950s. They are: Bliss Dam, Lower Salmon Falls Dam, and the two dams of the Upper Salmon Falls Project, Upper Salmon Falls Dam A, and Upper Salmon Falls Dam B.

Near the city of Twin Falls two waterfalls have been modified for hydropower, Shoshone Falls and Twin Falls. Collectively called the Shoshone Falls Project, they are old and relatively small dams, currently operated by Idaho Power. Above Twin Falls is Milner Dam, built in 1905, for irrigation and rebuilt in 1992, with hydroelectric production added. The dam and irrigation works are owned by Milner Dam, Inc, while the powerplant is owned by Idaho Power.

Above Milner Dam, most of the large dams are projects of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, built mainly for irrigation, some are hydroelectric as well. All part of the Bureau's Minidoka Project, the dams are: Minidoka Dam (built 1909), American Falls Dam (1927), Palisades Dam (1957), and Jackson Lake Dam on Jackson Lake (1911). These dams, along with two others and numerous irrigation canals, supply water to about 1.1 million acres (4,500 km²) in southern Idaho.[13]

The city of Idaho Falls operates the remaining large dam on the Snake River, Gem State Dam, along with several smaller associated dams, for hydroelectric and irrigation purposes.

There are many other dams on the tributaries of the Snake River, built mainly for irrigation. They are mainly operated by the Bureau of Reclamation, but also by local government and private owners.

While the many dams in the Snake River basin have transformed the region's economy, they have also had an adverse environmental effect on wildlife, most notably on wild salmon migrations.[14] Since the 1990s, some conservation organizations and fishermen are seeking to restore the lower Snake River and Snake River salmon and steelhead by removing four federally-owned dams on the lower Snake River.[15]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built four dams and locks on the lower Snake River to facilitate shipping. The lower Columbia River has likewise been dammed for navigation. Thus a deep shipping channel through locks and slackwater reservoirs for heavy barges exists from the Pacific Ocean to Lewiston, Idaho. Most barge traffic originating on the Snake River goes to deep-water ports on the lower Columbia River, such as Portland, Oregon.

The shipping channel is authorized to be at least 14 feet (4.3 m) deep and 250 feet (76 m) wide. Where river depths were less than 14 feet (4 m), the shipping channel has been dredged in most places. Dredging and redredging work is ongoing and actual depths vary over time.[16]

With a channel about 5 feet (1.5 m) deeper than the Mississippi River System, the Columbia and Snake rivers can float barges twice as heavy.[17]

Agricultural products from Idaho and eastern Washington are among the main goods transported by barge on the Snake and Columbia rivers. Grain, mainly wheat, accounts for more than 85 percent of the cargo barged on the lower Snake River, the majority bound for international ports. In 1998, over 123,000,000 bushels of grain were barged on the Snake. Before the completion of the lower Snake dams, grain from the region was transported by truck or rail to Columbia River ports around the Tri-Cities. Other products barged on the lower Snake River include peas, lentils, forest products, and petroleum.[16]

Among the negative consequences of the lower Snake River's navigational slackwater reservoirs are the flooding of historic and archaeological sites, the stilling of once famous rapids, the slowing of currents and an associated rising of water temperature, and a general decline in the ability of fish to migrate up and down the river, often times inhibiting their ability to procreate.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Google Earth elevation for GNIS source coordinates. Retrieved on April 29, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Google Earth elevation for GNIS mouth coordinates. Retrieved on April 29, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 J.C. Kammerer, Largest Rivers in the United States, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 Daniel S. Meatte, Summary of Western Snake River Prehistory, Digital Atlas of Idaho. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ E.S. Lohse, Manual for Archaeological Analysis: Field and Laboratory Analysis Procedures. Department of Anthropology Miscellaneous Paper No. 92-1 (revised). (Pocatello, Idaho: Idaho Museum of Natural History, 1993). Southeastern Snake River Basin Prehistory Digital Atlas of Idaho. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Cassandra Tate, Marmes Rockshelter, HistoryLink.org. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Idaho State Historical Society, Snake River Basin. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ 8.0 8.1 Elizabeth L. Orr and William N. Orr, Geology of the Pacific Northwest (New York: McGraw-Hill Co., Inc., 1996, ISBN 0-07-048018-4).

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, National Water-Quality Assessment Program-Upper Snake River Basin. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Northwest Power and Conservation Council, Snake River. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Erik Robinson, Pressure builds on Snake River dams, The Columbian. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Northwest Power and Conservation Council, Hydropower. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. Department of the Interior, Minidoka Project Idaho.

- ‚ÜĎ Erik Robinson, Breach Snake River dams, says ex-Secretary Babbitt, The Columbian. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Lynda V. Mapes, Changing currents‚ÄĒIn the endless fray over fish, dreams and decisions drift. The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 BST Associates, Lower Snake River Transportation Study Final Report. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Blaine Harden, A River Lost: The Life and Death of the Columbia (W.W. Norton & Company, 1996, ISBN 0-393-31690-4).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grossman, Elizabeth. 2002. Watershed: The Undamming of America. New York: Counterpoint. ISBN 9781582431086.

- Gulick, Bill. 1971. Snake River Country. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers. ISBN 9780870042157.

- Harden, Blaine. 1996. A River Lost: The Life and Death of the Columbia. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393316904.

- Orr, Elizabeth L., and William N. Orr. 1996. Geology of the Pacific Northwest. New York: McGraw-Hill Co., Inc. ISBN 0070480184.

- U.S. Department of the Interior. Minidoka Project Idaho. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Biogeography · Climatology & paleoclimatology · Coastal/Marine studies · Geodesy · Geomorphology · Glaciology · Hydrology & Hydrography · Landscape ecology · Limnology · Oceanography · Palaeogeography · Pedology · Quaternary Studies | |||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.