William H. Seward

| William Henry Seward | |

| |

24th United States Secretary of State

| |

| In office March 5, 1861 – March 4, 1869 | |

| Preceded by | Jeremiah S. Black |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Elihu B. Washburne |

| Born | May 16, 1801 Florida, New York, USA |

| Died | October 10 1872 (aged 71) Auburn, New York, USA |

| Political party | Whig, Republican |

| Spouse | Frances Adeline Seward |

| Profession | Lawyer, Land Agent, Politician |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

William Henry Seward, Sr. (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was a Governor of New York and United States Secretary of State under Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson.

Early life

Seward was born in Florida, a community (which since has incorporated as a village) in Orange County, New York. His parents were Dr. Samuel Sweezy Seward (December 5, 1768-August 4, 1849) and Mary Jennings Seward (November 27, 1769-December 11, 1844).

He attended Union College, studying law, and graduated in 1820, with high honors. He became an abolitionist, which meant he opposed the expansion of slavery and was pro-free soil, after observing the conditions of slavery while working in Georgia. He then read law in Florida, New York and Goshen, New York and joined his practice with his father-in-law, Judge Elijah Miller, in Auburn, New York. He stopped his law practice to become a politician when he was elected as a Whig to the New York senate. In 1838, he was elected Governor of New York, serving for two terms until 1842. As a state senator and governor, Seward promoted progressive political policies including prison reform and increased spending on education, including the idea of schools for immigrants taught in their own language and by members of their own religion. He married Frances Adeline Miller on October 20, 1824, after meeting in 1821. They raised six children:

- Augustus Henry Seward (1826–1876)

- Frederick William Seward (1830–1915)

- Cornelia Seward (1836–1837)

- William Henry Seward, Jr. (1839–1920)

- Olive Risley Seward (1841–1908 adopted)

- Frances Adeline "Fanny" Seward (1844–1866)

Services to the United States

He was elected United States Senator as a Whig in 1848 and emerged as the leader of its anti-slavery wing. Being a fellow Whig, Seward was a friend and supporter of President Zachary Taylor's during his run for the presidency saying, "He is the most gentle-looking and amiable of men." Seward was an opponent of the Fugitive Slave Act, and he defended runaway slaves in court. Seward believed that there was a "higher law" than the Constitution, claiming that slavery was morally wrong. He used this as a justification in defending runaways and in his support of personal liberty laws. In 1850 Seward voted against the Compromise of 1850 and claimed in a speech that if slavery were not abolished, America would become embroiled in a civil war. He continued to argue this point of view over the next ten years. He presented himself as the leading enemy of the Slave Power — that is the conspiracy of southern slaveowners to seize the government and defeat the progress of liberty.

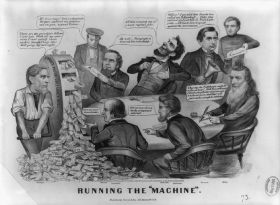

An 1864 cartoon featuring Seward, William Fessenden, Edwin Stanton, Abraham Lincoln and Gideon Welles takes a swing at the Lincoln administration.

With the decline in the fortunes of the Whig political Party, Seward joined the Republican Party in 1855 and was reelected senator from New York. By this time Seward had moderated his views and became less associated with the group known as the Radical Republicans. Seward lost the presidential nomination to John C. Frémont in 1856. He was expected to get the nomination in 1860 but many of the delegates feared that his radical past would prevent him from winning the election. However, radicals such as Horace Greeley also opposed him because they were angry at his shift to the right. Observing events from Europe, Karl Marx, who was ideologically sympathetic to Frémont, contemptuously regarded Seward as a "Republican Richelieu" and the "Demosthenes of the Republican Party" who had sabotaged Frémont's presidential ambitions. When Abraham Lincoln won the nomination Seward loyally supported him and made a long speaking tour of the West in the autumn of 1860.

Abraham Lincoln appointed him Secretary of State in 1861 and he served until 1869. During the War, Seward established a secret police force, which arrested thousands of citizens for disloyalty. Most who were arrested were engaged in sabotage, spying, disruption of the draft, or promoting insurrection [Neely 1991]. Few were properly political prisoners, but of those who were, this was often the result of overzealous generals. While the administration did not want to undermine the generals in the field, the existence of political prisoners was cause for embarrassment within the administration. Arrested citizens were not told the reason for their arrest, no investigation of their alleged wrongdoing was carried out, and no trials were held. Seward boasted to the British Ambassador, Lord Lyons, that he could have any man arrested in any state at a whim.

As Secretary of State, he argued that the United States must move westward. He fought for the U.S. purchase of Alaska, which he finally negotiated to acquire from Russia for $7,200,000 for 586,412 square miles (1,518,800 km²) of territory (more than twice the size of Texas), on March 30, 1867. This translated into approximately 2 cents per acre. The purchase of this frontier land was alternately mocked as "Seward's Folly," "Seward's Icebox," and Andrew Johnson's "polar bear garden." Currently, Alaska celebrates the purchase on Seward's Day, the last Monday of March.

He also engineered the annexation of the Danish Virgin Islands and the Bay of Samaná, and for American control of Panama; but the Senate did not ratify these treaties.

Assassination attempt

- Main Article: Abraham Lincoln assassination: William H. Seward

On April 14, 1865, Lewis Powell, an associate of John Wilkes Booth, attempted to assassinate Seward, the same night and at the same moment Abraham Lincoln was shot. Powell gained access to Seward's home by telling a servant, William Bell, that he was delivering medicine for Seward. Powell started up the stairs when then confronted by one of Seward's sons, Frederick. He told the intruder that his father was asleep and Powell began to start down the stairs, but suddenly swung around and pointed a gun at Frederick's head. After the gun misfired, Powell repeatedly swung the pistol over his head, leaving him in critical condition on the floor.

Powell then burst into William Seward's bedroom and stabbed him several times in the face and neck. Powell also attacked and injured two of Seward's other children, Augustus and Fanny, his nurse, Sergeant George F. Robinson, and a messenger, Emerick Hansell, who arrived just as Powell was escaping.

It is reported that when Seward awoke, his wife Frances Adeline Seward was attempting to serve him tea with a spoon. During the attack Seward was wearing a neck brace as a result of an accident about one month earlier, and it is said that this saved his life. However, he carried the facial scars from the attack for the remainder of his life. The events that happened that night put his wife and his daughter Fanny into complete shock and worry. Frances died June of 1865 and Fanny in October of 1866.

Powell was later captured and executed on July 7, 1865, along with David Herold, George Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt, three other conspirators in the Lincoln assassination.

Later life

After Ulysses S. Grant was elected president Seward decided to retire, and he spent his last years traveling and writing. He traveled around the world in fourteen months and two days from July, 1870 to September, 1871. On October 10, 1872, Seward died in his home in Auburn, New York, after having difficulty breathing. His last words were to his children saying, "Love one another." He was buried in Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York, with his wife and children. His headstone reads, “He was faithful.”

His son, Frederick, edited and published his memoirs.

Legacy

- $50-dollar Treasury notes, also called Coin notes, of the Series 1891, features a portrait of Seward on the obverse. Examples of this note are very rare and would likely sell for about $50,000.00 at auction.

- There is a street named after him in the city of Auburn, NY, Seward Ave. There are three other streets in Auburn, NY named after members of Seward's family. They are Frances St, Augustus St, and Frederick St. The four streets form a block.

- There is a street named after him, also Seward Ave, in Schenectady, New York, which forms the western border of the Union College campus.

- The city of Auburn, NY named one of its elementary school after him. Seward Elementary School. The village of Florida, NY, his birthplace, named its only high school after his father, Samuel Swazy Seward.

- The towns of Seward, Nebraska, Seward, Alaska, and the Seward Peninsula, also in Alaska, are named for him, as are Seward Park in Seattle, Washington, Seward Square park in Washington, D.C., and the Town of Seward, NY.

- There is a statue of him in Madison Square Park in New York City and in Volunteer Park in Seattle (facing towards Alaska).

- There is a peak in the Adirondack Mountains of New York named after the former senator; Seward Mountain (4361 feet).

- A park in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, as well the nearby housing cooperative are named after him.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Frederic Bancroft; The Life of William H. Seward 2 vol 1900

- David Herbert Donald. We Are Lincoln Men: Abraham Lincoln and His Friends (2003) pp 140-76.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (2005) ISBN 0-684-82490-6

- Hendrick, Burton. Lincoln's War Cabinet (1946)

- Mark E. Neely Jr.; The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties Oxford University Press 1991

- John M Taylor. William Henry Seward (1991)

- Van Deusen, Glyndon. William Henry Seward Oxford University Press, 1967

- Karl Marx. The Dismissal of Frémont Die Presse No. 325, November 26, 1861

- James L. Swanson, "Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer," (New York: HarperCollins 2006), 58-59.

- Holman Hamilton, Zachary Taylor: Soldier in the White House (1951)

Works

- Frederick William Seward. Autobiography of William H. Seward from 1801 to 1834: With a memoir of his life, and selections from his letters from 1831 to 1840 (1877)

- Commerce in the Pacific ocean. Speech of William H. Seward, in the Senate of the United States, July 29, 1852 (1852; Digitized page images & text)

- The continental rights and relations of our country. Speech of William Henry Seward, in Senate of the United States, January 26, 1853 (1853; Digitized page images & text)

- The destiny of America. Speech of William H. Seward, at the dedication of Capital University, at Columbus, Ohio, September 14, 1853 (1853; Digitized page images & text)

- Certificate of Exchange (1867; Digitized page images & text)

- Alaska. Speech of William H. Seward at Sitka, August 12, 1869 (1869; Digitized page images & text)

- The Works of William H. Seward. Edited by George E. Baker. Volume I of III (1853) online edition

- The Works of William H. Seward. Edited by George E. Baker. Volume II of III (1853) online edition

- The Works of William H. Seward: Vol. 5: The diplomatic history of the war for the union.. Edited by George E. Baker. Volume 5 (1890)

External links

- Seward House, Auburn, NY

- Brief Seward biography

- Mr. Lincoln and Friends: William H. Seward

- Mr. Lincoln and New York: William H. Seward

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: William H. Seward

- Works by William H. Seward. Project Gutenberg

- Pictures of US Treasury Notes featuring William Seward, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- William Henry Seward, the Virginia controversy, and the anti-slavery movement, 1839-1841

| Preceded by: William L. Marcy |

Governor of New York 1839 – 1842 |

Succeeded by: William C. Bouck |

| Preceded by: John A. Dix |

United States Senator (Class 3) from New York 1849 – 1861 |

Succeeded by: Ira Harris |

| Preceded by: Jeremiah S. Black |

United States Secretary of State 1861 – 1869 |

Succeeded by: Elihu B. Washburne |

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.