John Wilkes Booth

| John Wilkes Booth | |

John Wilkes Booth

| |

| Born | May 10 1838 |

|---|---|

| Died | April 26 1865 (aged 26) |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Parents | Junius Brutus Booth and Mary Ann Holmes |

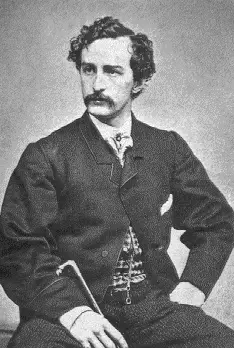

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American actor from Maryland, who fatally shot President of the United States Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. Lincoln died the next day from a single gunshot wound to the head, becoming the first American president to be assassinated.

Booth was a successful professional stage actor of his day and a member of the prominent Booth family of actors. He was also a Confederate sympathizer who expressed vehement dissatisfaction with the South's defeat in the Civil War and Lincoln's proposal to extend voting rights to freed slaves.

Booth, and a group of co-conspirators led by him, planned to kill Abraham Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward in a desperate bid to help the tottering Confederacy's cause. Although Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had surrendered four days earlier, Booth felt that the war was not yet over because Confederate General Joseph Johnston's army was still fighting Union Army General Sherman. Of the conspirators, only Booth was successful in carrying out his part of the plot.

Following the shooting, Booth fled by horseback to southern Maryland and eventually to a farm in rural northern Virginia, where he was tracked down and killed by Union soldiers two weeks later. Several of the other conspirators were tried and hanged shortly thereafter.

Background and early life

The noted British Shakespearean actor Junius Brutus Booth and his actress wife, Mary Ann Holmes, emigrated to the United States from England in 1821, purchasing a farm near Bel Air, Maryland, where John Wilkes Booth was born in 1838. He was named for the British revolutionary John Wilkes, whom the family claimed was a distant relative.[1]

Booth was educated in the classics, in particular Shakespeare. He attended the Bel Air Academy, where his headmaster described him as "Not deficient in intelligence, but disinclined to take advantage of the educational opportunities offered him. Each day, he rode back and forth from farm to school, taking more interest in what happened along the way than in reaching his classes on time."[2]

In 1850-1851, he attended Milton Boarding School for Boys located in Sparks, Maryland. As recounted by Booth's sister, Asia Booth Clarke, in her book entitled, The Unlocked Book, the future actor met an old Gypsy woman in the woods near the school who gave him a grim assessment of his life and said he would die young.[3] In 1851, at age 13, Booth attended St. Timothy's Hall, a military academy in Catonsville, Maryland. Following in the footsteps of their father (who had died in 1852), Booth and his brothers Edwin and Junius Brutus, Jr. would become well-known actors in mid-nineteenth century America.

Theatrical career and Civil War

At the age of 17, Booth played the Earl of Richmond in Shakespeare's Richard III, but did not act again until 1857, when he joined the stock company of the Arch Street Theatre in Philadelphia. At his request, he was billed as "J.B. Wilkes," a pseudonym meant to divert attention away from his famous thespian family. In 1858, he was accepted as a member of the Richmond Theatre, Virginia, stock company, and became increasingly popular, called "the handsomest man in America," by reviewers. He stood 5 feet, 8 inches tall, had jet-black hair, and was lean and athletic. He was also an excellent swordsman. His performances were often characterized by his contemporaries as acrobatic and intensely physical. A fellow actress once recalled that he occasionally cut himself with his own sword.

On December 2, 1859, Booth attended the hanging of militant abolitionist John Brown, who was executed for leading a raid on the Federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (in present-day West Virginia). Booth bought a uniform from a member of the Richmond Grays militia unit, which was heading for Charles Town, and he joined the Grays, who stood guard for Brown's trial. When Brown was hanged, Booth stood at the foot of the scaffold.

Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860, and the following month, Booth wrote a long speech that decried what he saw as Northern abolitionism and made clear his strong support of the South and the institution of slavery. On April 12, 1861, the Civil War erupted, and eventually eleven Southern states seceded from the Union. Booth's family was from Maryland, a border state which remained in the Union during the war despite a slave holding portion of the population that favored the Confederacy. Because Maryland shared a border with Washington, D.C., Lincoln declared martial law in Maryland and ordered the imprisonment of pro-secession Maryland political leaders at Ft. McHenry to prevent the state's secession, a move that many, including Booth, viewed as unconstitutional.

Although Booth was pro-Confederate, his family, like many Marylanders, was divided, and to preserve harmony among his brothers, Booth promised his mother that he would not enlist in the Confederate Army. As a popular actor in the 1860s, he traveled extensively to perform in both North and South, and as far west as New Orleans. Booth was outspoken in his love for the South, and equally outspoken in his hatred for Lincoln. In early 1862, Booth was arrested by a provost marshal in St. Louis for making anti-government remarks.

Booth and Lincoln crossed paths on several occasions. Lincoln was an avid theater-goer and especially loved Shakespeare. On November 9, 1863, President Lincoln saw Booth playing Raphael in Charles Selby's The Marble Heart at Ford's Theatre in Washington. At one point during the performance, Booth was said to have shaken his finger in Lincoln's direction as he delivered a line of dialogue. Lincoln sat in the same "presidential box" in which he would later be assassinated.

Assassination plot

By 1864, the tide of the war had shifted in the North's favor. The North halted prisoner exchange in an attempt to diminish the size of the Confederate Army, and because the Confederates refused to exchange captured African-American soldiers. Booth began devising a plan to kidnap Lincoln from his summer residence at the Old Soldiers Home three miles from the White House and smuggle him across the Potomac and into Richmond. He would be exchanged for the release of around 10,000 Southern soldiers held captive in Northern prisons. He successfully recruited his old friends Samuel Arnold and Michael O'Laughlin as accomplices.

Possible ties to the Confederacy

In the summer of 1864, Booth met with several well-known Confederate sympathizers at The Parker House in Boston, Massachusetts. In October 1864, he made an unexplained trip to Montreal. At the time, Montreal was a well known center of clandestine Confederate activities. He spent ten days in the city and stayed for a time at St. Lawrence Hall, a meeting place for the Confederate Secret Service, and met at least one blockade runner there. It is possible that it was here that he also met Confederate Secret Service director James D. Bulloch as well as George Nicholas Sanders, a one-time U.S. ambassador to Britain.

There has been much scholarly attention devoted to why Booth was in Montreal at this time, and what he was doing there. No solid evidence has ever linked Booth's kidnapping or assassination plot to a conspiracy involving any elements of the Confederate government.

The kidnapping attempt

Booth began to devote more and more of his energy and money to his plot to kidnap Abraham Lincoln after his re-election in early November 1864. He assembled a loose-knit band of Southern sympathizers, including David Herold, George Atzerodt, John Surratt, and Lewis Payne. They began to meet routinely at the boarding-house of Surratt's mother, Mrs. Mary Surratt.

On November 25, 1864, John Wilkes performed for the first and only time with his two brothers, Edwin and Junius, in a single engagement production of Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theater in New York. The proceeds went towards a statue of William Shakespeare for Central Park which still stands today. The performance was interrupted by a failed attempt by clandestine Confederate agents to burn down several hotels, and by extension the city of New York, with Greek fire. One of the hotels was next door to the theater, but the fire was quickly extinguished. The following morning, Booth argued bitterly with his brother, Edwin Booth, about Lincoln and the war.

Three months later, Booth attended Lincoln's second inauguration on March 4, 1865, as the invited guest of his secret fiancée, Lucy Hale. (Lucy's father, John P. Hale, was Lincoln's minister to Spain.) In the crowd below were Powell, Atzerodt, and Herold. There seems to have been no attempt to kidnap or assassinate Lincoln during the inauguration. Later, however, Booth remarked about "what a wonderful chance" he had to shoot Lincoln, if he had so chosen.

On March 17, Booth learned at the last minute that Lincoln would be attending a performance of the play Still Waters Run Deep at a hospital near the Soldier's Home. Booth assembled his team on a stretch of road near the Soldier's Home in the attempt to kidnap Lincoln en route to the hospital, but the president never showed up. Booth later learned that the President had changed his plans at the last moment to attend a reception at the National Hotel in Washington, which ironically was where Booth lived.

The assassination

On April 10, after hearing the news that Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox Court House, Booth told Louis J. Weichmann, a friend of John Surratt, and a boarder at Mary Surratt's house that he was done with the stage and that the only play he wanted to present henceforth was Venice Preserv'd. Although Mr. Weichmann did not understand the reference, Venice Preserv'd is about an assassination plot.

On April 11, Booth was in the crowd outside the White House when Lincoln gave an impromptu speech from his window. When Lincoln stated that he was in favor of granting suffrage to the former slaves, Booth turned to Lewis Powell and urged him to shoot the president on the spot. Powell refused. Booth muttered that it would be the last speech Lincoln would ever make.

On the morning of Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Booth learned that the President and Mrs. Lincoln would be attending the play, Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. He immediately set about making plans for the assassination, which included a getaway horse waiting outside, and an escape route. Booth informed Powell, Herold, and Atzerodt of his intention to kill Lincoln. He assigned Powell to assassinate Secretary of State Seward and Atzerodt to assassinate Vice-President Johnson. Herold would assist in their escape into Virginia. By targeting the President and his two immediate successors to the office, Booth seems to have intended to decapitate the Union government and throw it into a state of panic and confusion. Booth also planned to assassinate the Union commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant; however, Grant's wife had promised to visit family and so they were heading to New Jersey. Booth had hoped that the assassinations would create sufficient chaos within the Union that the Confederate government could reorganize and continue the war.

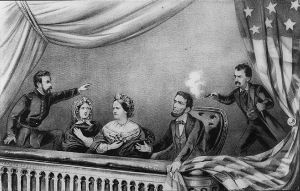

As a famous and popular actor, Booth was a friend of the owner of Ford's Theatre, John T. Ford, and had free access to all parts of the theater. Boring a spyhole into the presidential box earlier that day, the assassin could see if his intended victim had made it to the play. That evening, at around 10 p.m., as the play progressed, John Wilkes Booth slipped into Lincoln's box and shot him in the back of the head with a .44 caliber Deringer. Booth's escape was almost thwarted by Major Henry Rathbone, who was present in the Presidential box with Mrs. Mary Todd Lincoln.

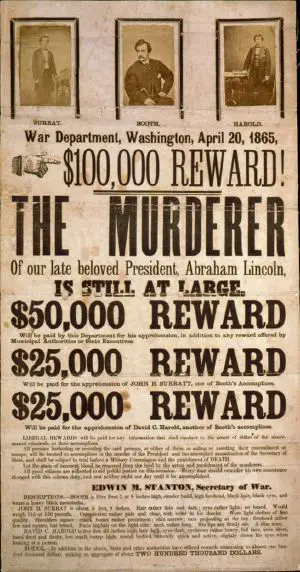

Wanted for murdering Abraham Lincoln

Booth then jumped from the President's box and fell to the stage, reputedly breaking his leg after it was caught by a U.S. Treasury Guard flag used for decoration. At least one researcher, Michael W. Kauffman, now believes, however, that Booth actually broke his leg when his horse fell on him later in the escape, and that Booth's diary entry claiming it occurred jumping to the stage is a typical Booth dramatization.[4] Some witnesses said he shouted, "Sic semper tyrannis" (Latin for "Thus always to tyrants," the Virginia state motto) from the stage, while others said he shouted "The South is avenged." He fled to the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, who treated the broken leg. Mudd was later convicted of conspiracy before a military court and sentenced to life in prison at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas islands, west of Key West, Florida. He was pardoned in 1869. Booth was surprised when he found little sympathy for his action, and wrote in his journal on April 21, five days before his capture, "[W]ith every man's hand against me, I am here in despair. And why; For doing what Brutus was honored for ... And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat."

Pursuit, capture, and death

Union soldiers, led by Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty of the 16th New York Cavalry Regiment, pursued Booth through Southern Maryland and across the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers to Richard Garrett's farm, just south of Port Royal, Caroline County, Virginia. Booth and his companion, David E. Herold, had been led to the farm by William S. Jett, formerly a private in the 9th Virginia Cavalry, whom they had met before crossing the Rappahannock.

Early in the morning of April 26, 1865, the soldiers caught up with Booth. Trapped in a tobacco barn owned by Richard H. Garrett, David Herold surrendered. Booth refused to surrender and Everton Conger ordered the soldiers to set the barn ablaze. Sergeant Boston Corbett fired at Booth—not against orders as some claim, as no orders were given—fatally wounding him in the neck. Booth was dragged from the fire and died on the porch of the nearby farmhouse at age 26. The bullet had severed his spinal cord, paralyzing him. His last words were reportedly, "Useless, useless."[5]

Booth's body was taken to the ironclad USS Montauk at the Washington Navy Yard for identification and an autopsy. The body was then buried in a storage room at the Old Penitentiary at the Washington Arsenal. When the prison was razed in 1867, the body was moved to a warehouse on the Arsenal grounds. In 1869, the remains were once again identified before being released to the Booth family, where they were buried in the family plot at Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore.

Conspiracy theories

A small red book, which was actually an 1864 appointment book kept as a diary, was found on the body of John Wilkes Booth on April 26, 1865. The date book was printed and sold by a St. Louis stationer named James M. Crawford. The book measured 6 by 3 1/2 inches and pictures of 5 women were found in the diary pockets. Booth's entries in the diary were probably written between April 17 and April 22, 1865. Mystery surrounds this diary. The little book was taken off Booth's body by Colonel Everton Conger. He took it to Washington and gave it to Lafayette C. Baker, chief of the War Department's National Detective Police. Baker in turn gave it to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. The book was not produced as evidence in the 1865 Conspiracy Trial. In 1867, the diary was "re-discovered" in a "forgotten" War Department file with 18 pages missing.

Over the years there has been endless speculation on those missing pages including rumors that they had surfaced. Nevertheless, they remain officially missing. Two of the pages were torn out by Booth himself and used to write messages to Dr. Richard H. Stuart on April 24, 1865. To speculate on their contents makes for interesting reading, but it's essentially fruitless, as no one knows for sure what the rest of the missing pages may or may not have contained.

Notes

- ↑ Genealogy Today, The Lincoln-Blair Affair. Retrieved September 15, 2007.

- ↑ Stanley Kimmel, The Mad Booths of Maryland (New York: Dover, 1970). ISBN 9780486222318

- ↑ Asia Booth Clarke, The Unlocked Book: A Memoir of John Wilkes Booth (New York: Arno Press, 1977). ISBN 9780405091377

- ↑ Michael W. Kauffman, American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies (New York: Random House, 2004). ISBN 9780375507854

- ↑ James L. Swanson, and Jonathan Davis, Manhunt: The Twelve-day Chase for Lincoln's Killer (Prince Frederick, Md: Recorded Books, 2006). ISBN 9781419383687

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clarke, Asia Booth. The Unlocked Book: A memoir of John Wilkes Booth. New York: Arno Press, 1977. ISBN 9780405091377

- Kauffman, Michael W. American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. New York: Random House, 2004. ISBN 9780375507854

- Kimmel, Stanley. The Mad Booths of Maryland. New York: Dover, 1970. ISBN 9780486222318

- Swanson, James L. and Jonathan Davis. Manhunt the Twelve-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Prince Frederick, Md: Recorded Books, 2006. ISBN 9781419383687

- Townsend, George Alfred. The Life, Crime, and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. New York: Lion Publishing, Inc., 1865. ISBN 9780976480532

External links

All links retrieved February 6, 2025.

- John Wilkes Booth at the Notable Names Database

- "The Death of John Wilkes Booth, 1865"

- Booth's grave site

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.