Difference between revisions of "Mind" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (81 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | [[File:Mr Pipo Enlightment.png|thumb|225px|"Enlightment"]] | ||

| + | '''Mind''' is a concept developed by self-conscious humans trying to understand what is the self that is [[conscious]] and how does that self relate to its perceived world. Most broadly, mind is the organized totality of the [[mental]] processes of an [[organism]] and the structural and functional components on which they depend. Taken more narrowly, as it often is in scientific studies, mind denotes only cognitive activities and functions, such as perceiving, attending, thinking, problem solving, language, learning, and memory.<ref>Gary R. VandenBos (ed.), ''APA Dictionary of Psychology'' (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007, ISBN 978-1591473800).</ref> Aspects of mind are also attributed to complex animals, which are commonly considered to be conscious. Studies in recent decades suggest strongly that the great apes have a level of self-consciousness as well. | ||

| − | '' | + | Philosophers have long sought to understand what is mind and its relationship to matter and the body. The Greek philosophers [[Plato]] and [[Aristotle]] between them defined the poles (monism and dualism) of much of the later discussion in the Western world on the question of mind—and much of the ambiguity as well.<ref>Robert L. Watson, ''The Great Psychologists: From Aristotle to Freud'' (Philadelphia and New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1963).</ref> Based on his world model that the perceived world is only a shadow of the real world of ideal Forms, Plato, a dualist, conceived of mind (or reason) as the facet of the tripartite soul that can know the Forms. The [[soul]] existed independent of the body, and its highest aspect, mind, was immortal. Aristotle, apparently both a monist and a dualist, insisted in ''The Soul'' that soul was unitary, that soul and body are aspects of one living thing, and that soul extends into all living things. Yet in other writings from another period of his life, Aristotle expressed the dualistic view that the knowing function of the human soul, the mind, is distinctively immaterial and eternal. |

| − | + | [[Saint Augustine]] adapted from the [[Neoplatonism]] of his time the dualist view of soul as being immaterial but acting through the body. He linked mind and soul closely in meaning. Some 900 years later, in an era of recovering the wisdom of Aristotle, Saint Thomas [[Aquinas]] identified the species, man, as being the composite substance of body and soul (or mind), with soul giving form to body, a monistic position somewhat similar to Aristotle's. Yet Aquinas also adopted a dualism regarding the rational soul, which he considered to be immortal. Christian views after Aquinas have diverged to cover a wide spectrum, but generally they tend to focus on soul instead of mind, with soul referring to an immaterial essence and core of human identity and to the seat of [[reason]], [[will]], [[conscience]], and higher [[emotion]]s. | |

| − | + | [[Rene Descartes]] established the clear mind-body [[dualism]] that has dominated the thought of the modern West. He introduced two assertions: First, that mind and soul are the same and that henceforth he would use the term mind and dispense with the term soul; Second, that mind and body were two distinct substances, one immaterial and one material, and the two existed independent of each other except for one point of interaction in the human brain. | |

| − | + | In the East, quite different theories related to mind were discussed and developed by [[Adi Shankara]], [[Siddhārtha Gautama]], and other ancient [[Indian Philosophy|Indian]] [[philosophy|philosophers]], as well as by Chinese scholars. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | As [[psychology]] became a science starting in the late nineteenth century and blossomed into a major scientific discipline in the twentieth century, the prevailing view in the scientific community came to be variants of [[physicalism]] with the assumption that all the functions attributed to mind are in one way or another derivative from activities of the brain. Countering this mainstream view, a small group of neuroscientists has persisted in searching for evidence suggesting the possibility of a human mind existing and operating apart from the brain. | ||

| − | ==Philosophical | + | In the late twentieth century as diverse technologies related to studying the mind and body have been steadily improved, evidence has emerged suggesting such radical concepts as: the mind should be associated not only with the brain but with the whole body; and the heart may be a center of consciousness complementing the brain. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Philosophical Perspectives== | ||

===Philosophy of mind=== | ===Philosophy of mind=== | ||

| − | + | {{Main|Philosophy of mind}} | |

| − | Philosophy of mind is the branch of [[philosophy]] that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and their relationship to the physical body. The ''mind-body problem'' | + | Philosophy of mind is the branch of [[philosophy]] that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and their relationship to the physical body. The ''mind-body problem,'' i.e., the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as the central issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body.<ref>J. Kim, "Problems in the Philosophy of Mind" in ''Oxford Companion to Philosophy,'' ed. Ted Honderich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).</ref> |

| − | + | [[File:Neuronal activity DARPA.jpg|thumb|250px|Neuronal activity in the brain]] | |

| − | + | Stated briefly, the mind-body problem is as follows: we believe ourselves to exist as both a physical body and a mind, and that these stand in some intimate relation. Our mind is involved in mental decisions giving rise to physical actions, and physical events (such as a finger being cut) give rise to mental events (such as a feeling of [[pain]]). One possible explanation for this correlation of mental functions and physical body experience is that the mind, which includes my sense of [[self]], is simply a product of the physical [[brain]]. On the other hand, the mind appears to possess features that no physical body does, including [[consciousness]] and simplicity (or unitary identity). Indeed, further reflection might lead us to conclude that the mind is ''entirely'' different from the body. Yet if that is correct, it is hard to see how mind and body could also have the intimate relation that they do have. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ''[[Dualism (philosophy of mind)|Dualism]]'' and ''[[monism]]'' are the two major schools of thought that attempt to resolve the mind-body problem. Dualism is the position that mind and body are separate from each other in some fundamental way. It can be traced back to [[Plato]]<ref>Plato, "Phaedo" in ''Plato Opera Volume I: Euthyphro, Apologia, Crito, Phaedo, Cratylus, Theaetetus, Sophista, Politicus,'' ed. E.A. Duke, W.F. Hicken, W.S.M. Nicoll, D.B. Robinson and J.C.G. Strachan, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).</ref> and [[Aristotle]],<ref>H. Robinson, ''Aristotelian dualism'' in ''Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy,'' Vol. 1, ed. Julia Annas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983).</ref><ref>M. C. Nussbaum, "Aristotelian dualism" in ''Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy,'' Vol. 2, ed. Julia Annas, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 197-207.</ref><ref>M. C. Nussbaum, and A. O. Rorty, ''Essays on Aristotle's De Anima'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992).</ref> but it was most precisely formulated by [[René Descartes]] in the seventeenth century.<ref name="De">René Descartes, ''Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy'' (Hacket Publishing Company, ISBN 0872204219).</ref> ''Substance dualists'' argue that the mind is an independently existing substance, whereas ''Property dualists'' maintain that the mind is or constitutively involves a group of independent properties that emerge from and cannot be reduced to physical properties of the brain, but that it is not a distinct substance.<ref name="Du">W.D. Hart, "Dualism," in Samuel Guttenplan, ''A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind'' (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), 265-267. </ref> | |

| − | '' | + | ''Monism'' is the position that mind and body are not [[ontology|ontologically]] distinct kinds of entities. This view appears to have first been advocated in Western Philosophy by [[Parmenides]] in the fifth century B.C.E. and was later espoused by the great seventeenth Century [[Rationalism|rationalist]] [[Baruch Spinoza]].<ref name="Spin">Baruch Spinoza, ''Tractatus Theologico-Politicus'' (A Theologico-Political Treatise), 1670.</ref> One type of monist, ''[[Physicalism|physicalists]],'' argue that only the entities postulated by physical theory exist, and that the mind can in principle be explained in terms of these entities. On the other hand, ''[[idealism (philosophy)|idealists]]'' maintain that the mind (along with its perceptions, thoughts, etc.) is all that exists and that the external world is either mental itself, or an illusion created by the mind. Finally, ''[[neutral monism|neutral monists]]'' adhere to the position that there is some other, neutral substance, and that both matter and mind are properties of this substance. The most common monisms in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have all been variations of physicalism; these positions include [[behaviorism]], the [[type physicalism|type identity theory]], [[anomalous monism]] and [[functionalism (philosophy of mind)|functionalism]].<ref name="Kim">J. Kim, "Mind-Body Problem," ''Oxford Companion to Philosophy,'' Ted Honderich (ed.) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | '' | + | Many modern philosophers of mind can be sorted into ''reductive'' vs. ''non-reductive'' varieties of physicalism, maintaining in their different ways that the mind is not something separate from the body.<ref name="Kim" /> ''Reductive physicalists'' assert that all mental states and properties will eventually be explained by scientific accounts of physiological processes and states.<ref name="Pat">Patricia Churchland, ''Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986, ISBN 0262031167).</ref><ref name="Paul">Paul Churchland, "Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes" ''Journal of Philosophy'' (1981): 67-90.</ref><ref name="Smart">J.J.C. Smart, "Sensations and Brain Processes" ''Philosophical Review'' (1956).</ref> ''Non-reductive physicalists'' argue that although the brain is all there ''is'' to the mind, the predicates and vocabulary used in mental descriptions and explanations are indispensable, and cannot be reduced to the language and lower-level explanations of physical science.<ref name="Davidson">Donald Davidson, ''Essays on Actions and Events'' (Oxford University Press, 1980, ISBN 0199246270).</ref><ref name="Pu">Hilary Putnam, "Psychological Predicates," in W. H. Capitan and D.D. Merrill, eds., ''Art, Mind and Religion'' (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1967).</ref> These approaches have been especially influential in the sciences, particularly in the fields of [[sociobiology]], [[computer science]], [[evolutionary psychology]] and the various [[neuroscience]]s.<ref name="PsyBio">J. Pinel, ''Psychobiology'' (Prentice Hall, Inc., 1990, ISBN 8815071741).</ref><ref name="LeDoux">J. LeDoux, ''The Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are.'' (New York: Viking Penguin, 2002, ISBN 8870787958).</ref><ref name=RussNor">S. Russell and P. Norvig, ''Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach'' (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0131038052).</ref><ref name="DawkRich">R. Dawkins, ''The Selfish Gene'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976).</ref> Other philosophers, however, adopt a non-physicalist position which challenges the notion that the mind is a purely physical construct.<ref name="Chalmersmind">David Chalmers, ''The Conscious Mind'' (Oxford University Press, 1997, ISBN 0195117891).</ref> |

| − | + | Continued neuroscientific progress has helped to clarify some of these issues. However, they are far from having been resolved, and modern philosophers of mind continue to ask how the subjective qualities and the intentionality (aboutness) of mental states and properties can be explained using the terms of the natural sciences.<ref name="Int">Daniel Dennett, ''The intentional stance'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998).</ref><ref name="Searleint">John Searle, ''Intentionality: A Paper on the Philosophy of Mind'' (Frankfurt: Nachdr. Suhrkamp, 2001, ISBN 3518285564).</ref> | |

===Mental faculties=== | ===Mental faculties=== | ||

| + | [[Plato]] in his various writings proposed different views of the mind, but he consistently held the view that mind is only one aspect of the [[soul]]. While he emphasized that the soul is unitary, he also argued that the soul has different aspects, one rational and the other irrational and comprising desires and appetites. The mind was the rational or reasoning aspect of soul. Since then, concepts and definitions of soul and of mind have varied widely as philosophers (and, more recently, psychologists) have worked to delineate the various functions, faculties, and aspects of the mind. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One useful pair of categories is [[rationalism]] and [[empiricism]], which in general represent two broad streams of philosophy looking at the phenomena of the sense of self that engages in thinking, sensing, feeling, deciding, and acting. Rationalists, represented by [[Plato]], [[Descartes]], and [[Leibniz]], tend to start with a system of metaphysical assumptions and then develop within that context their model of the human mind in which the ability to engage in abstract reasoning and mathematics is considered indicative of the mind's faculty of 'reason' by which truth can be recognized. By contrast, the tradition known as empiricism (perhaps most famously exemplified by [[Locke|John Locke]] and [[Hume|David Hume]]) aims to start with no metaphysical assumptions and build a model of the world and of the mind based on experiences of external and internal sensations. | ||

| − | + | Consideration of the mental faculties representing how the world ''is'' (such as belief and knowledge) and those representing how the world in some sense ''should be'' (such as desire) receive differing priority and value according to the thinker considering them. Plato, for instance, saw the desire for knowledge as emanating from [[reason]], the highest of faculties, while [[Emmanuel Kant|Kant]] explicitly assigned pure moral motivation to the faculty of reason. | |

| − | + | ==A Science of the Mind== | |

| + | [[Psychology]] is the study of human behavior and the mind. Originating as an area of philosophy, psychology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline with the establishment of the first laboratory of [[experimental psychology]] in Germany in 1879. As both an [[academic]] and [[applied science|applied]] discipline, psychology involves the [[science|scientific study]] of [[Mental function|mental processes]] such as [[perception]], [[cognition]], [[emotion]], and [[Personality psychology|personality]], as well as environmental influences from the society and culture, and [[interpersonal relationships]]. Psychology also refers to the application of such [[knowledge]] to various spheres of [[Human behavior|human activity]], including problems of individuals' [[everyday life|daily lives]] and the treatment of [[mental health]] problems. | ||

| − | + | Psychology differs from the other [[social sciences]] (e.g., [[anthropology]], [[economics]], [[political science]], and [[sociology]]) due to its focus on [[experiment]]ation at the scale of the individual, as opposed to [[group (sociology) | groups]] or [[institutions]]. Historically, psychology, beginning from a dualistic position, differed from [[biology]] and [[neuroscience]] in that it was primarily concerned with mind rather than brain. Modern psychological science, in contrast, incorporates [[Psychophysiology | physiological]] and [[neuropsychology | neurological]] processes into its conceptions of [[perception]], [[cognition]], behavior, and [[mental disorders]]. | |

| − | + | The field of psychology can be viewed as comprising three aspects of mind—cognition, affect, and conation—in which cognition concerns coming to know and understand, affect concerns emotional aspects of interpreting and responding to knowledge or information, and conation concerns choice and intention in motivation. In comparison with cognition and affect, whose implications for education have been well developed and implemented into education in the US, conation, important for self-direction and self-regulation, is the least well developed and implemented of the three.<ref>W. Huitt, [http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/conation/conation.html "Conation as an important factor of mind"] ''Educational Psychology Interactive'' (Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University, 1999). Retrieved May 4, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==The Brain and the Mind== | |

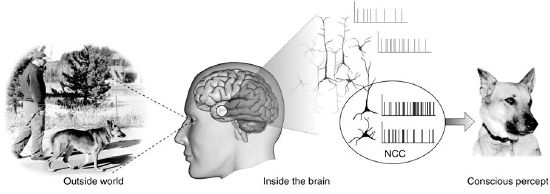

| − | + | [[File:Neural Correlates Of Consciousness.jpg|thumb|right|550px|Schema of the neural processes underlying [[consciousness]], from [[Christof Koch]]]] | |

| + | The "mind-body problem" concerning the explanation of the relationship, if any, between minds, or mental processes, and bodily states or processes is important not only to philosophy but also to the sciences, including [[psychology]], [[robotics]], and [[artificial intelligence]]. The question of how mind and [[brain]] are related remains unanswered after more than a century of investing ever larger amounts of resources in the development and use of ever more sophisticated technologies for studying the brain. | ||

| − | + | The brain is defined as the physical and biological [[matter]] contained within the [[skull]], responsible for all electrochemical neuronal processes. The mind, however, is seen in terms of mental attributes, such as beliefs, desires, attention, visual cognition, awareness, language, free choice, mental imagery, and sense of self and unitary identity. Concepts of mind remain greatly varied into the twenty-first century as the different mind concepts are tied to persistent differing views of the nature of the world. Outside the research laboratories and academic institutions, an implicit [[dualistic|dualism]]—assuming that "mental" phenomena are, in some respects, "non-physical" (distinct from the body)—prevails. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Far from uniform, these dualistic views range across a wide spectrum. Some adhere to [[metaphysics|metaphysically]] [[dualistic]] approaches in which the mind exists independently of the brain in some way, such as a [[soul]], [[epiphenomenalism|epiphenomenon]], or [[strong emergence|emergent]] phenomenon. Other dualistic views maintain that the mind is a distinct ''[[physics|physical]]'' phenomenon, such as an [[electromagnetism|electromagnetic field]] or a [[quantum mind|quantum effect]]. Some envision a physical mind mirroring the physical body and guiding its [[instinct|instinctual]] activities and development, while adding the concept for humans of a spiritual mind that mirrors a [[human body#The human body in religious and philosophical context|spiritual body]] and including aspects like philosophical and religious thought. | |

| − | + | Some [[materialist]]s believe that mentality is equivalent to [[behaviorism|behavior]] or [[functionalism|function]] or, in the case of [[computationalism|computationalists]] and [[strong AI]] theorists, [[computer software]] (with the brain playing the role of [[computer hardware|hardware]]). [[Idealism]], the belief that all is mind, still has some adherents. At the other extreme, [[eliminative materialism|eliminative materialist]]s believe that minds do not exist at all, and that mentalistic language will be replaced by neurological terminology. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | One Nobel prize winning neuroscientist, [[John Carew Eccles|Sir John Eccles]] (1903-1997) was a dualist interactionist believing that the human mind and brain are separate entities. In searching for a mechanism by which mind and brain could reasonably interact, that is without violating the [[law of conservation of energy]], he formulated the hypothesis that the interaction must occur through some kind of [[quantum mechanics|quantum]] level mechanism and a corresponding quantum level structure in the brain. His last book, published in 1994, discloses that he was finally able to propose, together with a quantum physicist, just such an hypothesis. It involves a quantum level effect on the probability that [[neurotransmitters]] will be released across some of the brain's trillions of [[synapse]]s.<ref>John C. Eccles, ''How the Self Controls Its Brain'' (Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3540562907).</ref> | |

| − | === | + | ===Artificial intelligence=== |

| − | + | The term [[Artificial Intelligence]] (AI) refers to "the science and engineering of making intelligent machines".<ref> John McCarthy, [http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/whatisai/whatisai.html What is Artificial Intelligence?] ''Stanford University''. Retrieved May 4, 2020.</ref> It can also refer to [[intelligence (trait)|intelligence]] as exhibited by an [[artificial]] (''man-made,'' ''non-natural,'' ''manufactured'') entity. AI is studied in overlapping fields of [[computer science]], [[psychology]], [[neuroscience]] and [[engineering]], dealing with intelligent [[behavior]], [[learn]]ing, and [[adapt]]ation, and usually developed using customized [[machine]]s or [[computer]]s. One of the biggest difficulties with AI is that of comprehension. Many devices have been created that can do amazing things, but critics of AI claim that no actual comprehension by the AI machine has taken place. | |

| − | + | The debate about the nature of the mind is relevant to the development of [[artificial intelligence]]. If the mind is a thing separate from the brain or higher than the functioning of the brain, then it would seem to be impossible to recreate mind within a machine. If, on the other hand, the mind is no more than the aggregated functions of the brain, then, in theory, it would be possible to create a machine with a recognizable mind (though possibly only with computers much different from today's), by simple virtue of the fact that such a machine already exists in the form of the human brain. | |

| − | + | ==Religious Pperspectives== | |

| + | Various religious traditions have contributed unique perspectives on the nature of mind. In many traditions, especially [[mysticism|mystical]] traditions, overcoming the [[Ego (spirituality)|ego]] is considered a worthy spiritual goal. | ||

| − | + | [[Judaism]] sees the human mind as one of the great wonders of [[Yahweh]]'s [[Creation according to Genesis|creation]]. [[Christianity]] has tended to see the mind as distinct from the [[soul]] (Greek ''[[nous]]'') and sometimes further distinguished from the [[spirit]]. [[Esotericism|Western esoteric traditions]] sometimes refer to a [[mental body]] that exists on a plane other than the physical. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Hinduism]]'s various philosophical schools have debated whether the human [[soul]] (Sanskrit ''[[atman]]'') is distinct from, or identical to, ''[[Brahman]],'' the [[divine]] [[reality]]. [[Buddhism]] attempted to break with such [[metaphysical]] speculation, and posited that there is actually no distinct thing as a human being, who merely consists of five aggregates, or ''[[skanda]]s.'' The [[India]]n [[philosopher]]-[[sage]] [[Sri Aurobindo]] attempted to unite the Eastern and Western psychological traditions with his [[integral psychology]], as have many philosophers and [[New religious movement]]s. | |

| − | + | [[Taoism]] sees the human being as contiguous with natural forces, and the mind as not separate from the [[body]]. [[Confucianism]] sees the mind, like the body, as inherently perfectible. | |

| − | + | ==Mental Health== | |

| − | + | By analogy with the health of the body, one can speak metaphorically of a state of health of the mind, or [[mental health]]. Mental health has typically been defined in terms of the emotional and psychological well-being needed to function in society and meet the ordinary demands of everyday life. According to the [[World Health Organization]] (WHO), there is no one "official" definition of mental health. Cultural differences, subjective assessments, and competing professional theories all affect how "mental health" is defined. In general, most experts agree that "mental health" and "[[mental illness]]" are not opposites. In other words, the absence of a recognized mental disorder is not necessarily an indicator of mental health. | |

| − | + | One way to think about mental health is by looking at how effectively and successfully a person functions. Feeling capable and competent; being able to handle normal levels of stress, maintaining satisfying relationships, and leading an independent life; and being able to "bounce back," or recover from difficult situations, are all signs of mental health. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Psychotherapy]] is an [[interpersonal]], [[relation]]al intervention used by trained psychotherapists to aid [[client]]s in problems of living. This usually includes increasing the individual sense of [[well-being]] and reducing subjective discomforting experience. Psychotherapists employ a range of techniques, such as [[dialogue]], [[communication]], and [[behavior]] change, that support experiential relationship building in order to improve the [[mental health]] of a client or patient, or to improve group relationships (such as in a [[family]]). Most forms of psychotherapy use only spoken [[conversation]], though some also use various other forms of communication such as the written word, [[art]], [[drama]], [[narrative]] story, or therapeutic touch. Psychotherapy occurs within a structured encounter between a trained [[therapist]] and client(s). Purposeful, theoretically based psychotherapy began in the 19th century with [[psychoanalysis]]; since then, scores of other approaches have been developed and continue to be created. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | ==The Future of the Mind== | ||

| − | + | Mind is one of a cluster of related concepts—including self, identity, soul, spirit, consciousness, reason, emotion, heart, appetites (desires), will, and body—whose definitions and boundaries are highly interdependent amongst themselves and at the same time highly culture dependent. A culture that prioritizes reason and intellect as foundations of knowledge, for example, will have a fundamentally different concept of mind from that of a culture that prioritizes silent meditation and the stilling of all rational thought as a foundation for knowing truth. As convergence of world cultures and scientific studies of the brain both continue, the question of what is the mind seems likely to remain unanswered and disputed. Any view of the mind that aims to be universal will need to account for: the persistent and widespread accounts of perception beyond the physical senses; increasingly strong evidence that mind is intimately at one with the body through the integrated nervous, immune, and endocrine systems; and that the physical heart is a seat of consciousness with the capacity to influence the functioning of the brain. | |

| − | + | ===Parapsychology=== | |

| − | + | Some views of the mind are grounded in anomalous experiences—reported persistently through history and throughout the world—of perceptions attained without use of the physical senses. According to the ''APA Dictionary of Psychology'',<ref>Gary R. VandenBos (ed.), ''APA Dictionary of Psychology'' (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007, ISBN 978-1591473800).</ref> [[parapsychology]] is the systematic study of alleged psychological phenomena involving the transfer of information or energy that cannot be explained in terms of presently known scientific data or laws. The types of phenomena studied—usually one of the various forms of clairvoyance or telepathy—are capacities of extrasensory perception whose proven existence would likely add strong support to the dualistic views of mind and require a radical reconfiguration of the scientific models of the mind and mental function. | |

| − | + | The scientific reality of parapsychological phenomena and the validity of scientific parapsychological research is a matter of frequent dispute and criticism. The field is regarded by critics as a [[pseudoscience]]. Parapsychologists, in turn, say that parapsychological [[research]] is [[science|scientifically]] rigorous. Despite criticisms, academic institutions in the U.S. and in Britain conduct research on the topic, employing laboratory methodologies and statistical techniques. The [[Parapsychological Association]] is the leading association for parapsychologists and has been a member of the [[American Association for the Advancement of Science]] since 1969.<ref name="ConsciousUniverse">Dean I. Radin, ''The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena'' (New York: HarperEdge, 1997, ISBN 0062515020).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===The bodymind model=== | |

| + | Models of the relation between mind and body depend significantly on the best understanding of the body, which, has progressed from observation of the gross structures—such as the brain, organs, muscles, bones, and the large blood vessels—revealed through dissection, to finer and finer details of structure down to the cellular and subcellular levels. In parallel, studies of the dynamic processes operating in the body at those different levels have also advanced. Through these complementary studies, clear models of different systems of the body have been developed. These systems include, the brain and nervous system, the endocrine system, the immune system, the digestive system, the blood system, and the skeletal. And through all of these discoveries the deliberations about the mind and body relationship have continued, often with the assumption that the mind, whatever it may be, is in some way correlated with the brain. | ||

| − | + | Research in the last two decades brings into question that presumed exclusive association of mind and brain, based on the discovery that molecules called neuroeptides affect emotion, mood, health, and memory. The neuropeptides are secreted by such different body components as the brain, gut, and gonads. Then the neuropeptides circulate in the blood until they bond to a [[receptor]] on a cell that may be in any of a multitude of locations, including the brain, gut, gonads, immune cells, or ganglia where nerves and clusters of cells converge at strategic locations throughout the body. Emotions may be felt throughout the body as the molecules of emotion are secreted and then captured by particular cells. Memories associated with emotions seem also to be coded in the body at the ganglia. | |

| − | + | Even the narrow definition of mind includes cognitive activities and functions, such as perceiving, attending, thinking, problem solving, language, learning, and memory. The growing evidence from neuropeptides circulating in the blood suggests a distribution of aspects of these functions into the body rather than their exclusive association with the brain. Such discoveries call into question the traditional images of both the brain as the singular control center of the body and of the mind as being exclusively associated with the brain, and point toward a new model of an integrated bodymind.<ref>Candace B. Pert, ''Molecules of Emotion: The Science Behind Mind-Body Medicine'' (New York: Scribner, 1997, ISBN 0684846349).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Heart mind=== |

| − | + | The heart is by far the most powerful organ in the body, emitting electromagnetic signals five thousand times more powerful than those of the brain. Unlike cells in the rest of the body, the billions of cells in the heart each pulsate individually and also in concert collectively. "Wisdom of the heart" and "knowing in my heart" are expressions found in many cultures. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | A new field of cardio-energetics operates from the basic premise that instead of the brain, the heart is the site of a human being's most basic feelings, thoughts, dreams, and fears. One might say that heart and brain in some way share the locus that is mind. While the perspective of heart would be one of a mind partnership with the brain, the brain perspective would be more likely to dominate any relationship with the heart. Like the brain, gut, and gonads, the heart also is also the site of receptors for and secretion of key neurotransmitters. The heart has its own center of neurons. | |

| − | + | Such factors as these and others are coming under close scrutiny because of the strong evidence that in some cases of heart transplant the heart recipient undergoes significant changes in personality, habits, and preferences, taking on characteristics of the heart donor. One example of many is of a young Hispanic man who received a heart transplant. The wife of the heart donor used the word "copacetic" when she met the heart recipient and placed her hand on his chest inside which her husband's heart was beating. The young man's mother then recounted that her son had started using "copacetic" regularly after the transplant, even though it is not a Spanish word and her son had not previously known it.<ref>Paul Pearsall, ''The Heart's Code: Tapping the Wisdom and Power of Our Heart Energy'' (New York: Broadway Books, 1998, ISBN 0767900774).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Chalmers, David | + | *Chalmers, David. ''The Conscious Mind.'' Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195117891 |

| − | *Churchland, Patricia | + | *Churchland, Patricia. ''Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain.'' MIT Press, 1986. ISBN 0262031167. |

| − | *Churchland, Paul | + | *Churchland, Paul. "Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes." ''Journal of Philosophy'' (1981): 67-90. |

| − | *Dawkins, R. | + | *Dawkins, R. ''The Selfish Gene.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0192860927 |

| − | *Dennett, Daniel | + | *Dennett, Daniel. ''The intentional stance.'' Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998. ISBN 0262540533. |

| − | *Donald | + | *Davidson, Donald. ''Essays on Actions and Events.'' Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0199246270. |

| − | *Hart, W.D. | + | *Eccles, John C. ''How the Self Controls Its Brain.'' Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 1994. ISBN 3540562907 |

| − | *Kim, J | + | *Hart, W.D. "Dualism," in Samuel Guttenplan (org). ''A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind.'' Oxford: Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 0631199969 |

| − | *LeDoux, J. | + | *Kim, J. "Mind-Body Problem," in ''Oxford Companion to Philosophy,'' new ed. Ted Honderich (ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0199264791 |

| − | *Nussbaum, M. C. | + | *LeDoux, J. ''The Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are.'' New York: Viking Penguin, 2002. ISBN 8870787958 |

| − | *Nussbaum, M. C. and | + | *Nussbaum, M. C. "Aristotelian dualism," ''Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy'' 2 (1984): 197-207. |

| − | *Pinel, J | + | *Nussbaum, M. C. and A. O. Rorty. ''Essays on Aristotle's De Anima.'' Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0198236009 |

| − | *Putnam, Hilary | + | *Pearsall, Paul. ''The Heart's Code: Tapping the Wisdom and Power of Our Heart Energy.'' New York: Broadway Books, 1998. ISBN 0767900774 |

| − | *Radin, D. I | + | *Pert, Candace B. ''Molecules of Emotion: The Science Behind Mind-Body Medicine.'' New York: Scribner, 1997. ISBN 0684846349 |

| − | *Robinson, H. | + | *Pinel, J. ''Psychobiology.'' Prentice Hall, Inc., 1990. ISBN 8815071741 |

| − | *Russell, S. and Norvig | + | *Putnam, Hilary. "Psychological Predicates," in W. H. Capitan and D. D. Merrill, eds., ''Art, Mind and Religion.'' Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1967. |

| − | *Searle, John | + | *Radin, D. I. ''The conscious universe: the scientific truth of psychic phenomena.'' New York, NY: HarperEdge, 1997. ISBN 0062515020 |

| − | *Smart, J.J.C | + | *Robinson, H. "‘Aristotelian dualism’," ''Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, 1'' (1983): 123-144. |

| + | *Russell, S. and P. Norvig. ''Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach.'' New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1995. ISBN 0131038052 | ||

| + | *Searle, John. ''Intentionality. A Paper on the Philosophy of Mind.'' Frankfurt a. M.: Nachdr. Suhrkamp, 2001. ISBN 3518285564 | ||

| + | *Smart, J.J.C. "Sensations and Brain Processes." ''Philosophical Review'' (1956). | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 9, 2022. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | * [http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/mendis/wheel322.html Abhidhamma | + | * [http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/mendis/wheel322.html The Abhidhamma in Practice]. |

| − | * [http://www.thymos.com Thymos - Piero Scaruffi's Studies on Consciousness, Cognition and Life] | + | * [http://www.thymos.com Thymos - Piero Scaruffi's Studies on Consciousness, Cognition and Life]. |

| − | * [http://www.aboutreincarnation.org/mind.php Buddhist View of the Mind] | + | * [http://www.aboutreincarnation.org/mind.php Buddhist View of the Mind]. |

| − | * [http://www.sciencedaily.com/news/mind_brain/ Current Scientific Research on the Mind and Brain] | + | * [http://www.sciencedaily.com/news/mind_brain/ Current Scientific Research on the Mind and Brain] ''ScienceDaily''. |

| − | + | ||

===General Philosophy Sources=== | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | ||

| − | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. |

| − | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. |

| − | + | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online]. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg]. | |

| − | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online] | ||

| − | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg] | ||

[[category:Philosophy and religion]] | [[category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:47, 9 November 2022

Mind is a concept developed by self-conscious humans trying to understand what is the self that is conscious and how does that self relate to its perceived world. Most broadly, mind is the organized totality of the mental processes of an organism and the structural and functional components on which they depend. Taken more narrowly, as it often is in scientific studies, mind denotes only cognitive activities and functions, such as perceiving, attending, thinking, problem solving, language, learning, and memory.[1] Aspects of mind are also attributed to complex animals, which are commonly considered to be conscious. Studies in recent decades suggest strongly that the great apes have a level of self-consciousness as well.

Philosophers have long sought to understand what is mind and its relationship to matter and the body. The Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle between them defined the poles (monism and dualism) of much of the later discussion in the Western world on the question of mind—and much of the ambiguity as well.[2] Based on his world model that the perceived world is only a shadow of the real world of ideal Forms, Plato, a dualist, conceived of mind (or reason) as the facet of the tripartite soul that can know the Forms. The soul existed independent of the body, and its highest aspect, mind, was immortal. Aristotle, apparently both a monist and a dualist, insisted in The Soul that soul was unitary, that soul and body are aspects of one living thing, and that soul extends into all living things. Yet in other writings from another period of his life, Aristotle expressed the dualistic view that the knowing function of the human soul, the mind, is distinctively immaterial and eternal.

Saint Augustine adapted from the Neoplatonism of his time the dualist view of soul as being immaterial but acting through the body. He linked mind and soul closely in meaning. Some 900 years later, in an era of recovering the wisdom of Aristotle, Saint Thomas Aquinas identified the species, man, as being the composite substance of body and soul (or mind), with soul giving form to body, a monistic position somewhat similar to Aristotle's. Yet Aquinas also adopted a dualism regarding the rational soul, which he considered to be immortal. Christian views after Aquinas have diverged to cover a wide spectrum, but generally they tend to focus on soul instead of mind, with soul referring to an immaterial essence and core of human identity and to the seat of reason, will, conscience, and higher emotions.

Rene Descartes established the clear mind-body dualism that has dominated the thought of the modern West. He introduced two assertions: First, that mind and soul are the same and that henceforth he would use the term mind and dispense with the term soul; Second, that mind and body were two distinct substances, one immaterial and one material, and the two existed independent of each other except for one point of interaction in the human brain.

In the East, quite different theories related to mind were discussed and developed by Adi Shankara, Siddhārtha Gautama, and other ancient Indian philosophers, as well as by Chinese scholars.

As psychology became a science starting in the late nineteenth century and blossomed into a major scientific discipline in the twentieth century, the prevailing view in the scientific community came to be variants of physicalism with the assumption that all the functions attributed to mind are in one way or another derivative from activities of the brain. Countering this mainstream view, a small group of neuroscientists has persisted in searching for evidence suggesting the possibility of a human mind existing and operating apart from the brain.

In the late twentieth century as diverse technologies related to studying the mind and body have been steadily improved, evidence has emerged suggesting such radical concepts as: the mind should be associated not only with the brain but with the whole body; and the heart may be a center of consciousness complementing the brain.

Philosophical Perspectives

Philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and their relationship to the physical body. The mind-body problem, i.e., the relationship of the mind to the body, is commonly seen as the central issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body.[3]

Stated briefly, the mind-body problem is as follows: we believe ourselves to exist as both a physical body and a mind, and that these stand in some intimate relation. Our mind is involved in mental decisions giving rise to physical actions, and physical events (such as a finger being cut) give rise to mental events (such as a feeling of pain). One possible explanation for this correlation of mental functions and physical body experience is that the mind, which includes my sense of self, is simply a product of the physical brain. On the other hand, the mind appears to possess features that no physical body does, including consciousness and simplicity (or unitary identity). Indeed, further reflection might lead us to conclude that the mind is entirely different from the body. Yet if that is correct, it is hard to see how mind and body could also have the intimate relation that they do have.

Dualism and monism are the two major schools of thought that attempt to resolve the mind-body problem. Dualism is the position that mind and body are separate from each other in some fundamental way. It can be traced back to Plato[4] and Aristotle,[5][6][7] but it was most precisely formulated by René Descartes in the seventeenth century.[8] Substance dualists argue that the mind is an independently existing substance, whereas Property dualists maintain that the mind is or constitutively involves a group of independent properties that emerge from and cannot be reduced to physical properties of the brain, but that it is not a distinct substance.[9]

Monism is the position that mind and body are not ontologically distinct kinds of entities. This view appears to have first been advocated in Western Philosophy by Parmenides in the fifth century B.C.E. and was later espoused by the great seventeenth Century rationalist Baruch Spinoza.[10] One type of monist, physicalists, argue that only the entities postulated by physical theory exist, and that the mind can in principle be explained in terms of these entities. On the other hand, idealists maintain that the mind (along with its perceptions, thoughts, etc.) is all that exists and that the external world is either mental itself, or an illusion created by the mind. Finally, neutral monists adhere to the position that there is some other, neutral substance, and that both matter and mind are properties of this substance. The most common monisms in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have all been variations of physicalism; these positions include behaviorism, the type identity theory, anomalous monism and functionalism.[11]

Many modern philosophers of mind can be sorted into reductive vs. non-reductive varieties of physicalism, maintaining in their different ways that the mind is not something separate from the body.[11] Reductive physicalists assert that all mental states and properties will eventually be explained by scientific accounts of physiological processes and states.[12][13][14] Non-reductive physicalists argue that although the brain is all there is to the mind, the predicates and vocabulary used in mental descriptions and explanations are indispensable, and cannot be reduced to the language and lower-level explanations of physical science.[15][16] These approaches have been especially influential in the sciences, particularly in the fields of sociobiology, computer science, evolutionary psychology and the various neurosciences.[17][18][19][20] Other philosophers, however, adopt a non-physicalist position which challenges the notion that the mind is a purely physical construct.[21]

Continued neuroscientific progress has helped to clarify some of these issues. However, they are far from having been resolved, and modern philosophers of mind continue to ask how the subjective qualities and the intentionality (aboutness) of mental states and properties can be explained using the terms of the natural sciences.[22][23]

Mental faculties

Plato in his various writings proposed different views of the mind, but he consistently held the view that mind is only one aspect of the soul. While he emphasized that the soul is unitary, he also argued that the soul has different aspects, one rational and the other irrational and comprising desires and appetites. The mind was the rational or reasoning aspect of soul. Since then, concepts and definitions of soul and of mind have varied widely as philosophers (and, more recently, psychologists) have worked to delineate the various functions, faculties, and aspects of the mind.

One useful pair of categories is rationalism and empiricism, which in general represent two broad streams of philosophy looking at the phenomena of the sense of self that engages in thinking, sensing, feeling, deciding, and acting. Rationalists, represented by Plato, Descartes, and Leibniz, tend to start with a system of metaphysical assumptions and then develop within that context their model of the human mind in which the ability to engage in abstract reasoning and mathematics is considered indicative of the mind's faculty of 'reason' by which truth can be recognized. By contrast, the tradition known as empiricism (perhaps most famously exemplified by John Locke and David Hume) aims to start with no metaphysical assumptions and build a model of the world and of the mind based on experiences of external and internal sensations.

Consideration of the mental faculties representing how the world is (such as belief and knowledge) and those representing how the world in some sense should be (such as desire) receive differing priority and value according to the thinker considering them. Plato, for instance, saw the desire for knowledge as emanating from reason, the highest of faculties, while Kant explicitly assigned pure moral motivation to the faculty of reason.

A Science of the Mind

Psychology is the study of human behavior and the mind. Originating as an area of philosophy, psychology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline with the establishment of the first laboratory of experimental psychology in Germany in 1879. As both an academic and applied discipline, psychology involves the scientific study of mental processes such as perception, cognition, emotion, and personality, as well as environmental influences from the society and culture, and interpersonal relationships. Psychology also refers to the application of such knowledge to various spheres of human activity, including problems of individuals' daily lives and the treatment of mental health problems.

Psychology differs from the other social sciences (e.g., anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology) due to its focus on experimentation at the scale of the individual, as opposed to groups or institutions. Historically, psychology, beginning from a dualistic position, differed from biology and neuroscience in that it was primarily concerned with mind rather than brain. Modern psychological science, in contrast, incorporates physiological and neurological processes into its conceptions of perception, cognition, behavior, and mental disorders.

The field of psychology can be viewed as comprising three aspects of mind—cognition, affect, and conation—in which cognition concerns coming to know and understand, affect concerns emotional aspects of interpreting and responding to knowledge or information, and conation concerns choice and intention in motivation. In comparison with cognition and affect, whose implications for education have been well developed and implemented into education in the US, conation, important for self-direction and self-regulation, is the least well developed and implemented of the three.[24]

The Brain and the Mind

The "mind-body problem" concerning the explanation of the relationship, if any, between minds, or mental processes, and bodily states or processes is important not only to philosophy but also to the sciences, including psychology, robotics, and artificial intelligence. The question of how mind and brain are related remains unanswered after more than a century of investing ever larger amounts of resources in the development and use of ever more sophisticated technologies for studying the brain.

The brain is defined as the physical and biological matter contained within the skull, responsible for all electrochemical neuronal processes. The mind, however, is seen in terms of mental attributes, such as beliefs, desires, attention, visual cognition, awareness, language, free choice, mental imagery, and sense of self and unitary identity. Concepts of mind remain greatly varied into the twenty-first century as the different mind concepts are tied to persistent differing views of the nature of the world. Outside the research laboratories and academic institutions, an implicit dualism—assuming that "mental" phenomena are, in some respects, "non-physical" (distinct from the body)—prevails.

Far from uniform, these dualistic views range across a wide spectrum. Some adhere to metaphysically dualistic approaches in which the mind exists independently of the brain in some way, such as a soul, epiphenomenon, or emergent phenomenon. Other dualistic views maintain that the mind is a distinct physical phenomenon, such as an electromagnetic field or a quantum effect. Some envision a physical mind mirroring the physical body and guiding its instinctual activities and development, while adding the concept for humans of a spiritual mind that mirrors a spiritual body and including aspects like philosophical and religious thought.

Some materialists believe that mentality is equivalent to behavior or function or, in the case of computationalists and strong AI theorists, computer software (with the brain playing the role of hardware). Idealism, the belief that all is mind, still has some adherents. At the other extreme, eliminative materialists believe that minds do not exist at all, and that mentalistic language will be replaced by neurological terminology.

One Nobel prize winning neuroscientist, Sir John Eccles (1903-1997) was a dualist interactionist believing that the human mind and brain are separate entities. In searching for a mechanism by which mind and brain could reasonably interact, that is without violating the law of conservation of energy, he formulated the hypothesis that the interaction must occur through some kind of quantum level mechanism and a corresponding quantum level structure in the brain. His last book, published in 1994, discloses that he was finally able to propose, together with a quantum physicist, just such an hypothesis. It involves a quantum level effect on the probability that neurotransmitters will be released across some of the brain's trillions of synapses.[25]

Artificial intelligence

The term Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to "the science and engineering of making intelligent machines".[26] It can also refer to intelligence as exhibited by an artificial (man-made, non-natural, manufactured) entity. AI is studied in overlapping fields of computer science, psychology, neuroscience and engineering, dealing with intelligent behavior, learning, and adaptation, and usually developed using customized machines or computers. One of the biggest difficulties with AI is that of comprehension. Many devices have been created that can do amazing things, but critics of AI claim that no actual comprehension by the AI machine has taken place.

The debate about the nature of the mind is relevant to the development of artificial intelligence. If the mind is a thing separate from the brain or higher than the functioning of the brain, then it would seem to be impossible to recreate mind within a machine. If, on the other hand, the mind is no more than the aggregated functions of the brain, then, in theory, it would be possible to create a machine with a recognizable mind (though possibly only with computers much different from today's), by simple virtue of the fact that such a machine already exists in the form of the human brain.

Religious Pperspectives

Various religious traditions have contributed unique perspectives on the nature of mind. In many traditions, especially mystical traditions, overcoming the ego is considered a worthy spiritual goal.

Judaism sees the human mind as one of the great wonders of Yahweh's creation. Christianity has tended to see the mind as distinct from the soul (Greek nous) and sometimes further distinguished from the spirit. Western esoteric traditions sometimes refer to a mental body that exists on a plane other than the physical.

Hinduism's various philosophical schools have debated whether the human soul (Sanskrit atman) is distinct from, or identical to, Brahman, the divine reality. Buddhism attempted to break with such metaphysical speculation, and posited that there is actually no distinct thing as a human being, who merely consists of five aggregates, or skandas. The Indian philosopher-sage Sri Aurobindo attempted to unite the Eastern and Western psychological traditions with his integral psychology, as have many philosophers and New religious movements.

Taoism sees the human being as contiguous with natural forces, and the mind as not separate from the body. Confucianism sees the mind, like the body, as inherently perfectible.

Mental Health

By analogy with the health of the body, one can speak metaphorically of a state of health of the mind, or mental health. Mental health has typically been defined in terms of the emotional and psychological well-being needed to function in society and meet the ordinary demands of everyday life. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there is no one "official" definition of mental health. Cultural differences, subjective assessments, and competing professional theories all affect how "mental health" is defined. In general, most experts agree that "mental health" and "mental illness" are not opposites. In other words, the absence of a recognized mental disorder is not necessarily an indicator of mental health.

One way to think about mental health is by looking at how effectively and successfully a person functions. Feeling capable and competent; being able to handle normal levels of stress, maintaining satisfying relationships, and leading an independent life; and being able to "bounce back," or recover from difficult situations, are all signs of mental health.

Psychotherapy is an interpersonal, relational intervention used by trained psychotherapists to aid clients in problems of living. This usually includes increasing the individual sense of well-being and reducing subjective discomforting experience. Psychotherapists employ a range of techniques, such as dialogue, communication, and behavior change, that support experiential relationship building in order to improve the mental health of a client or patient, or to improve group relationships (such as in a family). Most forms of psychotherapy use only spoken conversation, though some also use various other forms of communication such as the written word, art, drama, narrative story, or therapeutic touch. Psychotherapy occurs within a structured encounter between a trained therapist and client(s). Purposeful, theoretically based psychotherapy began in the 19th century with psychoanalysis; since then, scores of other approaches have been developed and continue to be created.

The Future of the Mind

Mind is one of a cluster of related concepts—including self, identity, soul, spirit, consciousness, reason, emotion, heart, appetites (desires), will, and body—whose definitions and boundaries are highly interdependent amongst themselves and at the same time highly culture dependent. A culture that prioritizes reason and intellect as foundations of knowledge, for example, will have a fundamentally different concept of mind from that of a culture that prioritizes silent meditation and the stilling of all rational thought as a foundation for knowing truth. As convergence of world cultures and scientific studies of the brain both continue, the question of what is the mind seems likely to remain unanswered and disputed. Any view of the mind that aims to be universal will need to account for: the persistent and widespread accounts of perception beyond the physical senses; increasingly strong evidence that mind is intimately at one with the body through the integrated nervous, immune, and endocrine systems; and that the physical heart is a seat of consciousness with the capacity to influence the functioning of the brain.

Parapsychology

Some views of the mind are grounded in anomalous experiences—reported persistently through history and throughout the world—of perceptions attained without use of the physical senses. According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology,[27] parapsychology is the systematic study of alleged psychological phenomena involving the transfer of information or energy that cannot be explained in terms of presently known scientific data or laws. The types of phenomena studied—usually one of the various forms of clairvoyance or telepathy—are capacities of extrasensory perception whose proven existence would likely add strong support to the dualistic views of mind and require a radical reconfiguration of the scientific models of the mind and mental function.

The scientific reality of parapsychological phenomena and the validity of scientific parapsychological research is a matter of frequent dispute and criticism. The field is regarded by critics as a pseudoscience. Parapsychologists, in turn, say that parapsychological research is scientifically rigorous. Despite criticisms, academic institutions in the U.S. and in Britain conduct research on the topic, employing laboratory methodologies and statistical techniques. The Parapsychological Association is the leading association for parapsychologists and has been a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science since 1969.[28]

The bodymind model

Models of the relation between mind and body depend significantly on the best understanding of the body, which, has progressed from observation of the gross structures—such as the brain, organs, muscles, bones, and the large blood vessels—revealed through dissection, to finer and finer details of structure down to the cellular and subcellular levels. In parallel, studies of the dynamic processes operating in the body at those different levels have also advanced. Through these complementary studies, clear models of different systems of the body have been developed. These systems include, the brain and nervous system, the endocrine system, the immune system, the digestive system, the blood system, and the skeletal. And through all of these discoveries the deliberations about the mind and body relationship have continued, often with the assumption that the mind, whatever it may be, is in some way correlated with the brain.

Research in the last two decades brings into question that presumed exclusive association of mind and brain, based on the discovery that molecules called neuroeptides affect emotion, mood, health, and memory. The neuropeptides are secreted by such different body components as the brain, gut, and gonads. Then the neuropeptides circulate in the blood until they bond to a receptor on a cell that may be in any of a multitude of locations, including the brain, gut, gonads, immune cells, or ganglia where nerves and clusters of cells converge at strategic locations throughout the body. Emotions may be felt throughout the body as the molecules of emotion are secreted and then captured by particular cells. Memories associated with emotions seem also to be coded in the body at the ganglia.

Even the narrow definition of mind includes cognitive activities and functions, such as perceiving, attending, thinking, problem solving, language, learning, and memory. The growing evidence from neuropeptides circulating in the blood suggests a distribution of aspects of these functions into the body rather than their exclusive association with the brain. Such discoveries call into question the traditional images of both the brain as the singular control center of the body and of the mind as being exclusively associated with the brain, and point toward a new model of an integrated bodymind.[29]

Heart mind

The heart is by far the most powerful organ in the body, emitting electromagnetic signals five thousand times more powerful than those of the brain. Unlike cells in the rest of the body, the billions of cells in the heart each pulsate individually and also in concert collectively. "Wisdom of the heart" and "knowing in my heart" are expressions found in many cultures.

A new field of cardio-energetics operates from the basic premise that instead of the brain, the heart is the site of a human being's most basic feelings, thoughts, dreams, and fears. One might say that heart and brain in some way share the locus that is mind. While the perspective of heart would be one of a mind partnership with the brain, the brain perspective would be more likely to dominate any relationship with the heart. Like the brain, gut, and gonads, the heart also is also the site of receptors for and secretion of key neurotransmitters. The heart has its own center of neurons.

Such factors as these and others are coming under close scrutiny because of the strong evidence that in some cases of heart transplant the heart recipient undergoes significant changes in personality, habits, and preferences, taking on characteristics of the heart donor. One example of many is of a young Hispanic man who received a heart transplant. The wife of the heart donor used the word "copacetic" when she met the heart recipient and placed her hand on his chest inside which her husband's heart was beating. The young man's mother then recounted that her son had started using "copacetic" regularly after the transplant, even though it is not a Spanish word and her son had not previously known it.[30]

Notes

- ↑ Gary R. VandenBos (ed.), APA Dictionary of Psychology (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007, ISBN 978-1591473800).

- ↑ Robert L. Watson, The Great Psychologists: From Aristotle to Freud (Philadelphia and New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1963).

- ↑ J. Kim, "Problems in the Philosophy of Mind" in Oxford Companion to Philosophy, ed. Ted Honderich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- ↑ Plato, "Phaedo" in Plato Opera Volume I: Euthyphro, Apologia, Crito, Phaedo, Cratylus, Theaetetus, Sophista, Politicus, ed. E.A. Duke, W.F. Hicken, W.S.M. Nicoll, D.B. Robinson and J.C.G. Strachan, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).

- ↑ H. Robinson, Aristotelian dualism in Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, Vol. 1, ed. Julia Annas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983).

- ↑ M. C. Nussbaum, "Aristotelian dualism" in Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, Vol. 2, ed. Julia Annas, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 197-207.

- ↑ M. C. Nussbaum, and A. O. Rorty, Essays on Aristotle's De Anima (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992).

- ↑ René Descartes, Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy (Hacket Publishing Company, ISBN 0872204219).

- ↑ W.D. Hart, "Dualism," in Samuel Guttenplan, A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), 265-267.

- ↑ Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (A Theologico-Political Treatise), 1670.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 J. Kim, "Mind-Body Problem," Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Ted Honderich (ed.) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- ↑ Patricia Churchland, Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986, ISBN 0262031167).

- ↑ Paul Churchland, "Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes" Journal of Philosophy (1981): 67-90.

- ↑ J.J.C. Smart, "Sensations and Brain Processes" Philosophical Review (1956).

- ↑ Donald Davidson, Essays on Actions and Events (Oxford University Press, 1980, ISBN 0199246270).

- ↑ Hilary Putnam, "Psychological Predicates," in W. H. Capitan and D.D. Merrill, eds., Art, Mind and Religion (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1967).

- ↑ J. Pinel, Psychobiology (Prentice Hall, Inc., 1990, ISBN 8815071741).

- ↑ J. LeDoux, The Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. (New York: Viking Penguin, 2002, ISBN 8870787958).

- ↑ S. Russell and P. Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0131038052).

- ↑ R. Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976).

- ↑ David Chalmers, The Conscious Mind (Oxford University Press, 1997, ISBN 0195117891).

- ↑ Daniel Dennett, The intentional stance (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998).

- ↑ John Searle, Intentionality: A Paper on the Philosophy of Mind (Frankfurt: Nachdr. Suhrkamp, 2001, ISBN 3518285564).

- ↑ W. Huitt, "Conation as an important factor of mind" Educational Psychology Interactive (Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University, 1999). Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ John C. Eccles, How the Self Controls Its Brain (Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3540562907).

- ↑ John McCarthy, What is Artificial Intelligence? Stanford University. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ Gary R. VandenBos (ed.), APA Dictionary of Psychology (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007, ISBN 978-1591473800).

- ↑ Dean I. Radin, The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena (New York: HarperEdge, 1997, ISBN 0062515020).

- ↑ Candace B. Pert, Molecules of Emotion: The Science Behind Mind-Body Medicine (New York: Scribner, 1997, ISBN 0684846349).

- ↑ Paul Pearsall, The Heart's Code: Tapping the Wisdom and Power of Our Heart Energy (New York: Broadway Books, 1998, ISBN 0767900774).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chalmers, David. The Conscious Mind. Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195117891

- Churchland, Patricia. Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain. MIT Press, 1986. ISBN 0262031167.

- Churchland, Paul. "Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes." Journal of Philosophy (1981): 67-90.

- Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0192860927

- Dennett, Daniel. The intentional stance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998. ISBN 0262540533.

- Davidson, Donald. Essays on Actions and Events. Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0199246270.

- Eccles, John C. How the Self Controls Its Brain. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 1994. ISBN 3540562907

- Hart, W.D. "Dualism," in Samuel Guttenplan (org). A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 0631199969

- Kim, J. "Mind-Body Problem," in Oxford Companion to Philosophy, new ed. Ted Honderich (ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0199264791

- LeDoux, J. The Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. New York: Viking Penguin, 2002. ISBN 8870787958

- Nussbaum, M. C. "Aristotelian dualism," Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 2 (1984): 197-207.

- Nussbaum, M. C. and A. O. Rorty. Essays on Aristotle's De Anima. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0198236009

- Pearsall, Paul. The Heart's Code: Tapping the Wisdom and Power of Our Heart Energy. New York: Broadway Books, 1998. ISBN 0767900774

- Pert, Candace B. Molecules of Emotion: The Science Behind Mind-Body Medicine. New York: Scribner, 1997. ISBN 0684846349

- Pinel, J. Psychobiology. Prentice Hall, Inc., 1990. ISBN 8815071741

- Putnam, Hilary. "Psychological Predicates," in W. H. Capitan and D. D. Merrill, eds., Art, Mind and Religion. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1967.

- Radin, D. I. The conscious universe: the scientific truth of psychic phenomena. New York, NY: HarperEdge, 1997. ISBN 0062515020

- Robinson, H. "‘Aristotelian dualism’," Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, 1 (1983): 123-144.

- Russell, S. and P. Norvig. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1995. ISBN 0131038052

- Searle, John. Intentionality. A Paper on the Philosophy of Mind. Frankfurt a. M.: Nachdr. Suhrkamp, 2001. ISBN 3518285564

- Smart, J.J.C. "Sensations and Brain Processes." Philosophical Review (1956).

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- The Abhidhamma in Practice.

- Thymos - Piero Scaruffi's Studies on Consciousness, Cognition and Life.

- Buddhist View of the Mind.

- Current Scientific Research on the Mind and Brain ScienceDaily.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.