Difference between revisions of "Euthanasia" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (94 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} | |

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Euthanasia machine (Australia).JPG|thumb|400px|A machine that can facilitate euthanasia through heavy doses of drugs. The laptop screen leads the user through a series of steps and questions to ensure they are fully prepared. The final injection is then done by motors controlled by the computer.]] | |

| + | '''Euthanasia''' (from [[Ancient Greek|Greek]]: ''ευθανασία -ευ,'' eu, "[[good]]," ''θάνατος,'' thanatos, "[[death]]") is the practice of terminating the [[life]] of a [[human being]] or [[animal]] with an incurable [[disease]], intolerable [[suffering]], or a possibly undignified death in a [[Pain and nociception|painless]] or minimally painful way, for the purpose of limiting suffering. It is a form of [[homicide]]; the question is whether it should be considered justifiable or [[crime|criminal]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Euthanasia refers both to the situation when a substance is administered to a person with intent to kill that person or, with basically the same intent, when removing someone from life support. There may be a legal divide between making someone die and letting someone die. In some instances, the first is (in some societies) defined as [[murder]], the other is simply allowing nature to take its course. Consequently, laws around the world vary greatly with regard to euthanasia and are constantly subject to change as cultural values shift and better palliative care or treatments become available. Thus, while euthanasia is legal in some nations, in others it is criminalized. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Of related note is the fact that [[suicide]], or attempted suicide, is no longer a criminal offense in most states. This demonstrates that there is consent among the states to self determination, however, the majority of the states argue that assisting in suicide is illegal and punishable even when there is written consent from the individual. The problem with written consent is that it is still not sufficient to show self-determination, as it could be coerced; if active euthanasia were to become legal, a process would have to be in place to assure that the patient's consent is fully voluntary. | ||

| − | '''Euthanasia''' | + | ==Terminology == |

| − | + | ===Euthanasia generally=== | |

| + | '''Euthanasia''' has been used with several meanings: | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Literally "good death," any peaceful [[death]]. | ||

| + | #Using an injection to kill a pet when it becomes homeless, old, sick, or feeble. | ||

| + | #The Nazi euphemism for Hitler's efforts to remove certain groups from the gene pool, particularly [[homosexuality|homosexual]]s, [[Jew]]s, [[Roma|gypsies]], and [[mental retardation|mentally handicapped]] people. | ||

| + | #Killing a patient at the request of the family. The patient is [[brain]] dead, [[coma]]tose, or otherwise incapable of letting it be known if he or she would prefer to live or die. | ||

| + | #Mercy killing. | ||

| + | #[[Physician]]-assisted [[suicide]]. | ||

| + | #Killing a terminally ill person at his request. | ||

| − | + | The term euthanasia is used only in senses (6) and (7) in this article. When other people debate about euthanasia, they could well be using it in senses (1) through (5), or with some other definition. To make this distinction clearer, two other definitions of euthanasia follow: | |

| − | |||

===Euthanasia by means=== | ===Euthanasia by means=== | ||

| − | There | + | There can be passive, non-aggressive, and aggressive euthanasia. |

| + | *Passive euthanasia is withholding common treatments (such as [[antibiotic]]s, [[drug]]s, or [[surgery]]) or giving a medication (such as [[morphine]]) to relieve pain, knowing that it may also result in death ([[principle of double effect]]). Passive euthanasia is currently the most accepted form as it is currently common practice in most hospitals. | ||

| + | *Non-aggressive euthanasia is the practice of withdrawing [[life support]] and is more controversial. | ||

| + | *Aggressive euthanasia is using lethal substances or force to bring about death, and is the most controversial means. | ||

| − | + | James Rachels has challenged both the use and moral significance of that distinction for several reasons: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>To begin with a familiar type of situation, a patient who is dying of incurable cancer of the throat is in terrible pain, which can no longer be satisfactorily alleviated. He is certain to die within a few days, even if present treatment is continued, but he does not want to go on living for those days since the pain is unbearable. So he asks the doctor for an end to it, and his family joins in this request. …Suppose the doctor agrees to withhold treatment. …The justification for his doing so is that the patient is in terrible agony, and since he is going to die anyway, it would be wrong to prolong his suffering needlessly. But now notice this. If one simply withholds treatment, it may take the patient longer to die, and so he may suffer more than he would if more direct action were taken and a lethal injection given. This fact provides strong reason for thinking that, once the initial decision not to prolong his agony has been made, active euthanasia is actually preferable to passive euthanasia, rather than the reverse.<ref>James Rachels, ''The End of Life: Euthanasia and Morality'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0192860705).</ref> </blockquote> | |

| − | === | + | ===Euthanasia by consent=== |

| − | There | + | There is also involuntary, non-voluntary, and voluntary euthanasia. |

| + | *Involuntary euthanasia is euthanasia against someone’s will and equates to [[murder]]. This kind of euthanasia is almost always considered wrong by both sides and is rarely debated. | ||

| + | *Non-voluntary euthanasia is when the person is not competent to or unable to make a decision and it is thus left to a proxy like in the [[Terri Schiavo]] case. Terri Schiavo, a Floridian who was believed to have been in a vegetative state since 1990, had her feeding tube removed in 2005. Her husband had won the right to take her off life support, which he claimed she would want but was difficult to confirm as she had no [[living will]]. This form is highly controversial, especially because multiple proxies may claim the authority to decide for the patient. | ||

| + | *Voluntary euthanasia is euthanasia with the person’s direct consent, but is still controversial as can be seen by the arguments section below. | ||

| − | == | + | ===Mercy killing=== |

| + | Mercy killing refers to killing someone to put them out of their [[suffering]]. The killer may or may not have the informed consent of the person killed. We shall use the term mercy killing only when there is no consent. Legally, mercy killing without consent is usually treated as [[murder]]. | ||

| − | + | ===Murder=== | |

| + | [[Murder]] is intentionally [[homicide|killing]] someone in an unlawful way. There are two kinds of murder: | ||

| + | |||

| + | *The murderer has the informed consent of the person killed. | ||

| + | *The murderer does not have the informed consent of the person killed. | ||

| − | + | In most parts of the world, types (1) and (2) murder are treated identically. In other parts, type (1) murder is excusable under certain special circumstances, in which case it ceases to be considered murder. Murder is, by definition, unlawful. It is a legal term, not a moral one. Whether euthanasia is murder or not is a simple question for lawyers—"Will you go to jail for doing it or won't you?" | |

| − | + | Whether euthanasia should be considered murder or not is a matter for legislators. Whether euthanasia is good or bad is a deep question for the individual citizen. A right to die and a pro life proponent could both agree "euthanasia is murder," meaning one will go to jail if he were caught doing it, but the right to die proponent would add, "but under certain circumstances, it should not be, just as it is not considered murder now in the Netherlands." | |

| − | + | ==History== | |

| + | The term "euthanasia" comes from the [[Greek]] words “eu” and “thanatos,” which combined means “good death.” [[Hippocrates]] mentions euthanasia in the [[Hippocratic Oath]], which was written between 400 and 300 B.C.E. The original Oath states: “To please no one will I prescribe a deadly drug nor give advice which may cause his death." | ||

| − | + | Despite this, the ancient Greeks and Romans generally did not believe that life needed to be preserved at any cost and were, in consequence, tolerant of [[suicide]] in cases where no relief could be offered to the dying or, in the case of the [[Stoics]] and [[Epicureans]], where a person no longer cared for his life. | |

| − | + | The [[English Common Law]] from the 1300s until today also disapproved of both suicide and assisting suicide. It distinguished a suicide, who was by definition of unsound mind, from a felo-de-se or "evildoer against himself," who had coolly decided to end it all and, thereby, perpetrated an “infamous crime.” Such a person forfeited his entire estate to the crown. Furthermore his corpse was subjected to public indignities, such as being dragged through the streets and hung from the gallows, and was finally consigned to "ignominious burial," and, as the legal scholars put it, the favored method was beneath a crossroads with a stake driven through the body. | |

| − | === | + | ===Modern history=== |

| + | Since the nineteenth century, euthanasia has sparked intermittent debates and activism in North America and Europe. According to medical historian Ezekiel Emanuel, it was the availability of [[anesthesia]] that ushered in the modern era of euthanasia. In 1828, the first known anti-euthanasia law in the United States was passed in the state of [[New York]], with many other localities and states following suit over a period of several years. | ||

| − | + | Euthanasia societies were formed in England, in 1935, and in the U.S., in 1938, to promote aggressive euthanasia. Although euthanasia legislation did not pass in the U.S. or England, in 1937, doctor-assisted euthanasia was declared legal in [[Switzerland]] as long as the person ending the life has nothing to gain. During this period, euthanasia proposals were sometimes mixed with [[eugenics]]. | |

| + | [[File:Alkoven Schloss Hartheim 2005-08-18 3589.jpg|thumb|350px|Hartheim Euthanasia Centre, where over 18,000 people were killed in the Nazi program known as Action T4]] | ||

| + | While some proponents focused on voluntary euthanasia for the terminally ill, others expressed interest in involuntary euthanasia for certain eugenic motivations (targeting those such as the mentally "defective"). Meanwhile, during this same era, U.S. court trials tackled cases involving critically ill people who requested physician assistance in dying as well as “mercy killings,” such as by parents of their severely disabled children.<ref>Yale Kamisar, “Some Non-religious Views against Proposed 'Mercy-killing' Legislation” in ''Death, Dying, and Euthanasia'' edited by Dennis J. Horan and David Mall. (Praeger, 1980, ISBN 978-0313270925). </ref> | ||

| − | + | Prior to [[World War II]], the [[Nazi]]s carried out a controversial and now-condemned euthanasia program. In 1939, Nazis, in what was code named [[Action T4]], involuntarily euthanized children under three who exhibited mental retardation, physical deformity, or other debilitating problems whom they considered "unworthy of life.” This program was later extended to include older children and adults. | |

| − | + | ===Post-War history=== | |

| − | + | [[Leo Alexander]], a judge at the [[Nuremberg trials]] after World War II, employed a "slippery slope" argument to suggest that any act of mercy killing inevitably will lead to the mass killings of unwanted persons: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>The beginnings at first were a subtle shifting in the basic attitude of the physicians. It started with the acceptance of the attitude, basic in the euthanasia movement, that there is such a thing as life not worthy to be lived. This attitude in its early stages concerned itself merely with the severely and chronically sick. Gradually, the sphere of those to be included in this category was enlarged to encompass the socially unproductive, the ideologically unwanted, the racially unwanted and finally all non-Germans.<ref>Peter Singer, ''Writings on an Ethical Life'' (Ecco, 2000, ISBN 978-0060198381).</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Critics of this position point to the fact that there is no relation at all between the Nazi "euthanasia" program and modern debates about euthanasia. The Nazis, after all, used the word "euthanasia" to camouflage mass [[murder]]. All victims died involuntarily, and no documented case exists where a terminal patient was voluntarily killed. The program was carried out in the closest of secrecy and under a [[dictatorship]]. One of the lessons that we should learn from this experience is that secrecy is not in the public interest. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | However, due to outrage over Nazi euthanasia crimes, in the 1940s and 1950s, there was very little public support for euthanasia, especially for any involuntary, [[eugenics]]-based proposals. [[Catholic]] church leaders, among others, began speaking against euthanasia as a violation of the [[sanctity of life]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Nevertheless, owing to its [[principle of double effect]], Catholic [[moral theology]] did leave room for shortening life with pain-killers and what would could be characterized as passive euthanasia (Papal statements 1956-1957). On the other hand, judges were often lenient in mercy-killing cases.<ref>Derek Humphry and Ann Wickett, ''The Right to Die: Understanding Euthanasia'' (Carol Publishing Company, 1991, ISBN 978-0960603091).</ref> | |

| − | + | During this period, prominent proponents of euthanasia included [[Glanville Williams]]<ref>Dennis J. Baker and Jeremy Horder (eds), ''The Sanctity of Life and the Criminal Law: The Legacy of Glanville Williams'' (Cambridge University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1107536241).</ref> and clergyman [[Joseph Fletcher]].<ref>Joseph F. Fletcher, ''Morals and Medicine: The Moral Problems of the Patient's Right to know the Truth, Contraception, Artificial Insemination, Sterilization, Euthanasia'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1954. ISBN 978-0691072340).</ref> By the 1960s, advocacy for a right-to-die approach to voluntary euthanasia increased. | |

| − | |||

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | + | A key turning point in the debate over voluntary euthanasia (and physician-assisted dying), at least in the United States, was the public furor over the case of [[Karen Ann Quinlan]]. In 1975, Karen Ann Quinlan, for reasons still unknown, ceased breathing for several minutes. Failing to respond to mouth-to mouth resuscitation by friends she was taken by ambulance to a hospital in New Jersey. Physicians who examined her described her as being in "a chronic, persistent, vegetative state," and later it was judged that no form of treatment could restore her to cognitive life. Her father asked to be appointed her legal guardian with the expressed purpose of discontinuing the respirator which kept Karen alive. After some delay, the Supreme Court of New Jersey granted the request. The respirator was turned off. Karen Ann Quinlan remained alive but comatose until June 11, 1985, when she died at the age of 31. | |

| − | |||

| − | In [[ | + | In 1990, [[Jack Kevorkian]], a [[Michigan]] physician, became infamous for encouraging and assisting people in committing [[suicide]] which resulted in a Michigan law against the practice in 1992. Kevorkian was later tried and convicted in 1999, for a [[murder]] displayed on [[television]]. Meanwhile in 1990, the Supreme Court approved the use of non-aggressive euthanasia. |

| − | + | ==Influence of religious policies== | |

| + | [[Suicide]] or attempted suicide, in most states, is no longer a [[crime|criminal]] offense. This demonstrates that there is consent among the states to self determination, however, the majority of the states postulate that assisting in suicide is illegal and punishable even when there is written consent from the individual. Let us now see how individual [[religion]]s regard the complex subject of euthanasia. | ||

| − | === | + | ===Christian religions=== |

| + | ====Roman Catholic policy==== | ||

| + | In [[Catholic]] [[medical ethics]], official pronouncements tend to strongly oppose ''active euthanasia,'' whether voluntary or not. Nevertheless, Catholic moral theology does allow dying to proceed without medical interventions that would be considered "extraordinary" or "disproportionate." The most important official Catholic statement is the Declaration on Euthanasia.<ref name=Declaration>Sacred congregation for the doctrine of the faith. [https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19800505_euthanasia_en.html ''The Declaration on Euthanasia.''] The Vatican, 1980. Retrieved August 5, 2022. </ref> | ||

| − | + | The Catholic policy rests on several core principles of Catholic medical ethics, including the [[sanctity of human life]], the [[dignity]] of the human person, concomitant [[human rights]], and due [[proportionality]] in casuistic remedies.<ref name=Declaration/> | |

| − | === | + | ====Protestant policies==== |

| + | [[Protestant]] denominations vary widely on their approach to euthanasia and physician assisted death. Since the 1970s, Evangelical churches have worked with Roman Catholics on a [[sanctity of life]] approach, though the Evangelicals may be adopting a more exceptionless opposition. While liberal Protestant denominations have largely eschewed euthanasia, many individual advocates (such as [[Joseph Fletcher]]) and euthanasia society activists have been Protestant clergy and laity. As physician assisted dying has obtained greater legal support, some liberal Protestant denominations have offered religious arguments and support for limited forms of euthanasia. | ||

| − | Not unlike the trend among Protestants, Jewish movements have become divided over euthanasia since the 1970s. Generally, [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jewish]] thinkers oppose voluntary euthanasia, often vigorously, | + | ====Jewish policies==== |

| + | Not unlike the trend among Protestants, [[Jewish]] movements have become divided over euthanasia since the 1970s. Generally, [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jewish]] thinkers oppose voluntary euthanasia, often vigorously, though there is some backing for voluntary passive euthanasia in limited circumstances ([[Daniel Sinclair]], [[Moshe Tendler]], [[Shlomo Zalman Auerbach]], [[Moshe Feinstein]]). Likewise, within the [[Conservative Judaism]] movement, there has been increasing support for passive euthanasia. In [[Reform Judaism]] [[responsa]], the preponderance of anti-euthanasia sentiment has shifted in recent years to increasing support for certain passive euthanasia. | ||

===Non-Abrahamic religions=== | ===Non-Abrahamic religions=== | ||

| + | ====Buddhism and Hinduism==== | ||

| + | In [[Theravada Buddhism]], a monk can be expelled for praising the advantages of death, even if they simply describe the miseries of life or the bliss of the [[afterlife]] in a way that might inspire a person to commit [[suicide]] or pine away to death. In caring for the terminally ill, one is forbidden to treat a patient so as to bring on death faster than would occur if the disease were allowed to run its natural course. | ||

| − | In [[ | + | In [[Hinduism]], the Law of [[Karma]] states that any bad action happening in one lifetime will be reflected in the next. Euthanasia could be seen as murder, and releasing the Atman before its time. However, when a body is in a vegetative state, and with no quality of life, it could be seen that the Atman has already left. When [[avatar]]s come down to earth they normally do so to help out humankind. Since they have already attained [[Moksha]] they choose when they want to leave. |

| − | [[ | + | ====Islam==== |

| − | + | [[Muslim]]s are against euthanasia. They believe that all human life is sacred because it is given by [[Allah]], and that Allah chooses how long each person will live. Human beings should not interfere in this. Euthanasia and suicide are not included among the reasons allowed for killing in Islam. | |

| − | |||

| + | "Do not take life, which Allah made sacred, other than in the course of justice" (Qur'an 17:33). | ||

| + | "If anyone kills a person—unless it be for murder or spreading mischief in the land—it would be as if he killed the whole people" (Qur'an 5:32). | ||

| − | + | The Prophet said: "Amongst the nations before you there was a man who got a wound, and growing impatient (with its pain), he took a knife and cut his hand with it and the blood did not stop till he died. Allah said, 'My Slave hurried to bring death upon himself so I have forbidden him (to enter) Paradise'" (Sahih Bukhari 4.56.669). | |

| − | + | ==Senicide== | |

| + | '''Senicide''', or '''geronticide''', is the killing of the [[Old age|elderly]], or their abandonment to death. Various justifications for the practice have been used, including that it was mercy killing that prevented old people from extended suffering; or that it was done for the good of the whole, as the old people were no longer useful and were a burden on their family or the society, for example when the food supply was too low to feed everyone. Such practices have been recorded in many different cultures in history, although some cases may be more [[myth]] than reality. | ||

| − | === | + | ===Cultures practicing senicide in history=== |

| − | + | The case of institutionalized senicide occurring in Ancient Rome comes from a proverb stating that 60-year-olds were to be thrown from the bridge (''sexagenarios de ponte deici oportet''), and a ceremony in which effigies were thrown off in place of actual living persons.<ref>Kenneth Quinn, ''Catullus: The Poems'' (Bristol Classical Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1853994975).</ref> The most comprehensive explanation of the tradition comes from Festus writing in the fourth century CE who provides several different beliefs of the origin of the act, including human sacrifice by ancient Roman natives, a Herculean association, and the notion that older men should not vote because they no longer provided a duty to the state.<ref name="Parkin-2003" /> This idea to throw older men into the river probably coincides with the last explanation given by Festus. That is, younger men did not want the older generations to overshadow their wishes and ambitions and, therefore, suggested that the old men should be thrown off the bridge, where voting took place, and not be allowed to vote. | |

| − | + | Parkin provides a number of cases of senicide which the people of antiquity believed happened.<ref name="Parkin-2003">Tim G. Parkin, ''Old Age in the Roman World'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0801871283).</ref> Of these cases, only two of them occurred in Greek society; another took place in Roman society, while the rest happened in other cultures. One example that Parkin provides is of the island of [[Keos]] in the [[Aegean Sea]]. Although many different variations of the Keian story exist, the legendary practice may have begun when the Athenians besieged the island. In an attempt to preserve the food supply, the Keians voted for all people over 60 years of age to commit [[suicide]] by drinking [[hemlock]].<ref name="Parkin-2003"/> The other case of Roman senicide occurred on the island of [[Sardinia]], where human sacrifices of 70-years-old fathers were made by their sons to the titan [[Cronus]]. | |

| − | + | Scythian tribes were reputed to practice senicide. According to [[Herodotus]], the Massagetae: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Though they fix no certain term to life, yet when a man is very old all his family meet together and kill him, with beasts of the flock besides, then boil the flesh and feast on it. This is held to be the happiest death; when a man dies of an illness, they do not eat him, but bury him in the earth, and lament that he did not live to be killed.<ref name="Parkin-2003"/></blockquote> | |

| − | + | According to Aelian, The Derbiccae (a tribe, apparently of Scythian origin, settled in Margiana, on the left bank of the Oxus) kill those who are seventy years of age. They sacrifice the men and strangle the women.<ref>Jeffrey Henderson, [https://www.loebclassics.com/view/aelian-historical_miscellany/1997/pb_LCL486.183.xml ''Aelian: Historical Miscellany'' Book IV: Chapter 3] Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved August 6, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Pomponius Mela commented on people of India: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Some kill their neighbors and parents, in manner of sacrifice, before they pine away with age and sickness, and think it not only lawful, but also godly, to eat the bowels of them when they have killed them. But if they be attacked with old age or sickness, they get them out of all company into the wilderness, and there without sorrowing for the matter, abide the end of their life. The wiser sort of them, which are trained up in the profession and study of wisdom, linger not for death, but hasten it, by throwing themselves into the fire, which is counted a glory.<ref name="Gillel"/></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Herodotus]] says of the Padeans of [[India]]: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Other Indians, to the east of these, are nomads and eat raw flesh; they are called Padaei. It is said to be their custom that when anyone of their fellows, whether man or woman, is sick, a man's closest friends kill him, saying that if wasted by disease he will be lost to them as meat; though he denies that he is sick, they will not believe him, but kill and eat him. When a woman is sick, she is put to death like the men by the women who are her close acquaintances. As for one that has come to old age, they sacrifice him and feast on his flesh; but not many reach this reckoning, for before that everyone who falls ill they kill.<ref name="Gillel">Michael Gilleland, [https://laudatortemporisacti.blogspot.com/2012/06/senicide-part-i.html Senicide, Part I] ''Laudator Temporis Acti'', June 25, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In earlier times [[Inuit]] would leave their elderly on the ice to die but it was rare, except during [[famine]]s.<ref>Wendell H. Oswalt, ''Eskimos and Explorers'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0803286139).</ref> When food is not sufficient, the elderly are the least likely to survive. In the extreme case of famine, the Inuit fully understood that, if there was to be any hope of obtaining more food, a hunter was necessarily the one to feed on whatever food was left. | |

| − | In | ||

| − | + | While such a situation would lead to some loss of life, the elderly were not the first choice. In a culture with an [[oral history]], elders are the keepers of communal knowledge, effectively the community library. Because they are of extreme value as the repository of knowledge, there are cultural [[taboo]]s against sacrificing elders.<ref>Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley, ''A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit'' (Waveland Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1577663843). </ref> | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Given the importance that Eskimos attached to the aged, it is surprising that so many Westerners believe that they systematically eliminated elderly people as soon as they became incapable of performing the duties related to hunting or sewing.<ref>Ernest S. Burch, ''The Eskimos'' (University of Oklahoma Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0806121260).</ref></blockquote><blockquote></blockquote> | |

| − | + | However, a common response to desperate conditions and the threat of starvation was [[infanticide]]. A mother might abandon an infant in hopes that someone less desperate might find and adopt the child before the cold or animals killed it. The belief that the Inuit regularly resorted to infanticide may be due in part to studies done by Asen Balikci.<ref>Asen Balikci, ''The Netsilik Eskimo'' (Waveland Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0881334357)</ref> Other recent research has noted that: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>While there is little disagreement that there were examples of infanticide in Inuit communities, it is presently not known the depth and breadth of these incidents. The research is neither complete nor conclusive to allow for a determination of whether infanticide was a rare or a widely practiced event.<ref>Andrew Hund, "Inuit" in Brigitte H. Bechtold and Donna Cooper Graves (eds.), ''An Encyclopedia of Infanticide'' (Edwin Mellen Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0773414020).</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Senicide myths=== | |

| − | + | [[File:Suecia 3-049 ; Ättestupa.jpg|thumb|400px|Ättestupa in [[Västergötland]] as depicted by [[Willem Swidde]] in Erik Dahlbergh, ''Suecia antiqua et hodierna'' (1705)]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In [[Scandinavia]]n [[folklore]], the ''[[ättestupa]]'' is a cliff where elderly people were said to leap, or be thrown, to death. According to legend, this was done when old people were unable to support themselves or assist in a household. The name supposedly denotes sites where ritual senicide took place during pagan Nordic prehistoric times: | |

| + | <blockquote>In the “collective memory” of the treatment of old people in bygone days, the idea of the “suicidal precipice” (Swedish ättestupa) plays a major role: old people in pagan times were thought to have fallen to their deaths off a cliff, whether voluntarily jumping or being pushed.<ref>Lauritz Ulrik Absalon Weibull, ''Scandia'' 62 (1996): 365.</ref></blockquote> | ||

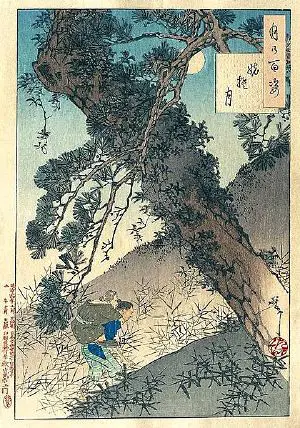

| − | + | [[File:Yoshitoshi - 100 Aspects of the Moon - 97.jpg|thumb|300px|''Ubasute no tsuki'' (The Moon of Ubasute), by [[Yoshitoshi]]]] | |

| + | ''[[Ubasute]]'' (姥捨, 'abandoning an old woman'), was a custom allegedly performed in [[Japan]] in the distant past, whereby an infirm or elderly relative was carried to a mountain, or some other remote, desolate place, and left there to die.<ref>Michael Hoffman, [https://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2010/09/12/general/aging-through-the-ages Aging through the ages] ''The Japan Times'', September 12, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2022. </ref> Most have concluded, however, that ''ubasute'' "is the subject of legend, but ... does not seem ever to have been a common custom."<ref> Alan Campbell and David S. Noble (eds.), ''Japan, An Illustrated Encyclopedia'' (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1993, ISBN 978-4062059381), 1121.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ''Lapot'' is a mythical [[Serbia]]n practice of disposing of one's parents, or other elderly family members, once they become a financial burden on the family. According to Georgevitch (Đorđević), writing in 1918 about the eastern highlands of Serbia, in the region of [[Zaječar District|Zaječar]], the killing was carried out with an axe or stick, and the entire village was invited to attend. In some places corn mush was put on the head of the victim to make it seem as if the corn, not the family, was the killer.<ref name="folk-lore">T.R. Georgevitch, 3 September 1918 The Killing of the Khazar Kings ''Folk-Lore'' 29(3) (September 30, 1918), 238-247.</ref> | |

| − | = | + | Georgevitch suggests that this legend may have originated in tales surrounding the [[Moesia Superior|Roman occupation]] of local forts.<blockquote> |

| + | The Romans ... were very bellicose people. Their leader ordered all the holders of the fort up to forty years of age to be active fighters, from forty to fifty to be guards of the fort, and after fifty to be killed, because they have no military value. Since that period the old men were killed.<ref name="folk-lore"/> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | However, Jovanović argued that this interpretation confused myth with reality. The well-known story of a grandson who hid his grandfather to protect him from lapot after a bad harvest, then bringing him back to the village when the old man's wisdom had shown a way to survive, was the basis for establishing that the old should be respected for their knowledge and wise counsel.<ref>Zarko Trebješanin, [http://www.nin.co.rs/2000-05/18/12726.html Lapot: naučni mit ili stvarnost] ''NIN'', May 18, 2000. Retrieved August 6, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | === | + | === Contemporary occurrences === |

| + | In the southern Indian state of [[Tamil Nadu]], senicide – known locally as ''[[thalaikoothal]]'' – is said to occur dozens or perhaps hundreds of times each year despite being illegal.<ref>Mark Magnier, [https://www.latimes.com/world/la-xpm-2013-jan-15-la-fg-india-mercy-killings-20130116-story.html In southern India, relatives sometimes quietly kill their elders] ''Los Angeles Times'', January 15, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | + | However it may be disguised as a ritual, ''thalaikoothal'' is actually a crude practice of killing the elderly because the family can no longer afford to take care of them. In India, only passive euthanasia (withholding common treatments) is legal which means that the killing of aged parents by any of the diverse methods that have become available, such as lethal injections or overdosed on sleeping pills, is illegal. | |

| + | The practice is justified as a kindness: | ||

| + | <blockquote>What else can they do if they see their parents suffering? At least they are offering their parents a peaceful death. ... It is an act of dignity because living like a piece of log for years is disrespectful for the elderly themselves, more than for us. The elderly choose to be offered thalaikoothal.<ref name=Mathew>Soumya Mathew, [https://soumyamathew94.wordpress.com/2016/04/16/thalaikoothal-killing-of-the-already-withering/ Thalaikoothal; killing of the already withering] ''The Kaleidoscope'', April 13, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2022. </ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | ==General conclusions== | ||

| + | The debate in the [[ethics]] literature on euthanasia is just as divided as the debate on physician-assisted suicide, perhaps more so. "Slippery-slope" arguments are often made, supported by claims about abuse of voluntary euthanasia in the [[Netherlands]]. | ||

| − | + | Arguments against it are based on the integrity of [[medicine]] as a profession. In response, autonomy and quality-of-life-base arguments are made in support of euthanasia, underscored by claims that when the only way to relieve a dying patient's pain or [[suffering]] is terminal sedation with loss of [[consciousness]], [[death]] is a preferable alternative—an argument also made in support of physician-assisted suicide. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | To summarize, there may be some circumstances when euthanasia is the morally correct action, however, one should also understand that there are real concerns about legalizing euthanasia because of fear of misuse and/or overuse and the fear of the slippery slope leading to a loss of respect for the value of life. What is needed are improvements in research, the best palliative care available, and above all, people should, perhaps, at this time begin modifying [[homicide]] laws to include motivational factors as a legitimate defense. | |

| − | + | Just as homicide is acceptable in cases of [[self-defense]], it could be considered acceptable if the motive is [[mercy]]. Obviously, strict parameters would have to be established that would include patients' request and approval, or, in the case of incompetent patients, advance directives in the form of a [[living will]] or [[family]] and [[court]] approval. | |

| − | + | Mirroring this attitude, there are countries and/or states—such as [[Albania]] (in 1999), [[Australia]] (1995), [[Belgium]] (2002), The [[Netherlands]] (2002), the U.S. state of [[Oregon]], and Switzerland (1942)—that, in one way or other, have legalized euthanasia; in the case of Switzerland, a long time ago. | |

| − | + | In others, such as UK and U.S., discussion has moved toward ending its illegality. On November 5, 2006, Britain's [[Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists]] submitted a proposal to the [[Nuffield Council on Bioethics]] calling for consideration of permitting the euthanasia of [[disabled]] [[newborn]]s. The report did not address the current illegality of euthanasia in the [[United Kingdom]], but rather calls for reconsideration of its viability as a legitimate medical practice. The [[United States Supreme Court]] ruled on the [[constitutionality]] of assisted suicide, in 2000, recognizing individual interests and deciding how, rather than whether, they will die. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Perhaps a fitting conclusion of the subject could be the Japanese suggestion of the [[Law governing euthanasia]]: | ||

| + | *In the case of "passive euthanasia," three conditions must be met: | ||

| + | #The patient must be suffering from an incurable [[disease]], and in the final stages of the disease from which he/she is unlikely to make a recovery. | ||

| + | #The patient must give express consent to stopping treatment, and this consent must be obtained and preserved prior to death. If the patient is not able to give clear consent, their consent may be determined from a pre-written document such as a [[living will]] or the testimony of the family. | ||

| + | #The patient may be passively euthanized by stopping medical treatment, [[chemotherapy]], [[dialysis]], artificial respiration, blood transfusion, IV drip, and so forth. | ||

| + | *For "active euthanasia," four conditions must be met: | ||

| + | #The patient must be suffering from unbearable physical pain. | ||

| + | #Death must be inevitable and drawing near. | ||

| + | #The patient must give consent. (Unlike passive euthanasia, living wills and family consent will not suffice.) | ||

| + | #The physician must have (ineffectively) exhausted all other measures of pain relief. | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | *Baker, Dennis J., and Jeremy Horder (eds). ''The Sanctity of Life and the Criminal Law: The Legacy of Glanville Williams''. Cambridge University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1107536241 | ||

| + | *Balikci, Asen. ''The Netsilik Eskimo''. Waveland Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0881334357 | ||

| + | *Battin, Margaret P., Rosamond Rhodes, and Anita Silvers (eds.). ''Physician Assisted Suicide: Expanding the Debate''. New York: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 978-0415920025 | ||

| + | *Bechtold, Brigitte H., and Donna Cooper Graves (eds.). ''An Encyclopedia of Infanticide''. Edwin Mellen Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0773414020 | ||

| + | *Campbell, Alan, and David S. Noble (eds.). ''Japan, An Illustrated Encyclopedia''. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1993. ISBN 978-4062059381 | ||

| + | *Dworkin, R.M. ''Life's Dominion: An Argument About Abortion, Euthanasia, and Individual Freedom''. New York: Vintage, 1994. ISBN 978-0679733195 | ||

| + | *Fletcher, Joseph F. ''Morals and Medicine: The Moral Problems of the Patient's Right to know the Truth, Contraception, Artificial Insemination, Sterilization, Euthanasia.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1954. ISBN 978-0691072340 | ||

| + | *Horan, Dennis J., and David Mall (eds.). ''Death, Dying, and Euthanasia.'' Praeger, 1980. ISBN 978-0313270925 | ||

| + | *Humphry, D. and Ann Wickett. ''The Right to Die: Understanding Euthanasia.'' Carol Publishing Company, 1991. ISBN 978-0960603091 | ||

| + | * Kawagley, Angayuqaq Oscar. ''A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit''. Waveland Press, 2006 ISBN 978-1577663843 | ||

| + | *Kopelman, Loretta M., and Kenneth A. deVille (eds.). ''Physician-assisted Suicide: What are the Issues?'' Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht 2001. ISBN 978-0792371427 | ||

| + | *Oswalt, Wendell H. ''Eskimos and Explorers''. University of Nebraska Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0803286139 | ||

| + | *Parkin, Tim G. ''Old Age in the Roman World''. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0801871283 | ||

| + | *Quinn, Kenneth. ''Catullus: The Poems''. Bristol Classical Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1853994975 | ||

| + | *Rachels, James, ''The End of Life: Euthanasia and Morality.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0192860705 | ||

| + | *Sacred congregation for the doctrine of the faith. [https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19800505_euthanasia_en.html ''The Declaration on Euthanasia.''] The Vatican, 1980. Retrieved August 5, 2022. | ||

| + | *Singer, Peter. ''Writings on an Ethical Life''. Ecco, 2000. ISBN 978-0060198381 | ||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| − | + | All links retrieved March 23, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[http://www.rsrevision.com/Alevel/ethics/euthanasia/index.htm Euthanasia: A dignified death?] - a UK site that looks at the issues, case studies, and ethical, and Christian responses | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.rsrevision.com/Alevel/ethics/euthanasia/index.htm | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Support=== | ===Support=== | ||

| − | * [ | + | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/euthanasia-voluntary/ Voluntary Euthanasia] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://finalexitnetwork.org/ Final Exit Network] provides guides to self-deliverance for the terminally and hopelessly ill to end their suffering |

| − | + | * [https://www.compassionandchoices.org/ Compassion & Choices] - provides education, support and advocacy for the choice-in-dying movement | |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.dignityindying.org.uk/ Dignity in Dying] - leading campaigning organisation promoting patient choice at the end of life |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://wfrtds.org/ World Federation of Right To Die Societies] |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.narcissistic-abuse.com/euthanasia.html Euthanasia and the Right to Life] |

| − | * [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Opposition=== | ===Opposition=== | ||

| − | + | *[http://www.watton.org/ethics/topics/euthansia/ Euthanasia] ''Watton on the Web'' - Christian Study on euthanasia | |

| − | + | *[https://www.carenotkilling.org.uk/ Care, NOT Killing] - a UK alliance promoting palliative care, opposing euthanasia and assisted suicide | |

| − | *[http://www.watton.org/ethics/topics/euthansia/ Christian Study on euthanasia | + | *[http://www.euthanasia.com/ Euthanasia.com] |

| − | *[ | + | *[http://www.starcourse.org/euthanasia.htm Non-Religious Arguments against 'Voluntary Euthanasia'] |

| − | *[http://www.euthanasia.com/ | + | *[https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_25031995_evangelium-vitae.html A Papal encyclical dealing with a number of issues of life and death including euthanasia] |

| − | + | *[https://rosicrucian.com/zineen/suicide.htm Suicide and Euthanasia] ''Rosicrucian Fellowship'' | |

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.starcourse.org/euthanasia.htm Non- | ||

| − | *[ | ||

| − | *[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ----- | |

| − | {{Credits|Euthanasia|133620986|}} | + | {{Death}} |

| + | {{Credits|Euthanasia|133620986|Senicide|1097661605}} | ||

| + | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Law]] | ||

Latest revision as of 04:44, 23 March 2024

Euthanasia (from Greek: ευθανασία -ευ, eu, "good," θάνατος, thanatos, "death") is the practice of terminating the life of a human being or animal with an incurable disease, intolerable suffering, or a possibly undignified death in a painless or minimally painful way, for the purpose of limiting suffering. It is a form of homicide; the question is whether it should be considered justifiable or criminal.

Euthanasia refers both to the situation when a substance is administered to a person with intent to kill that person or, with basically the same intent, when removing someone from life support. There may be a legal divide between making someone die and letting someone die. In some instances, the first is (in some societies) defined as murder, the other is simply allowing nature to take its course. Consequently, laws around the world vary greatly with regard to euthanasia and are constantly subject to change as cultural values shift and better palliative care or treatments become available. Thus, while euthanasia is legal in some nations, in others it is criminalized.

Of related note is the fact that suicide, or attempted suicide, is no longer a criminal offense in most states. This demonstrates that there is consent among the states to self determination, however, the majority of the states argue that assisting in suicide is illegal and punishable even when there is written consent from the individual. The problem with written consent is that it is still not sufficient to show self-determination, as it could be coerced; if active euthanasia were to become legal, a process would have to be in place to assure that the patient's consent is fully voluntary.

Terminology

Euthanasia generally

Euthanasia has been used with several meanings:

- Literally "good death," any peaceful death.

- Using an injection to kill a pet when it becomes homeless, old, sick, or feeble.

- The Nazi euphemism for Hitler's efforts to remove certain groups from the gene pool, particularly homosexuals, Jews, gypsies, and mentally handicapped people.

- Killing a patient at the request of the family. The patient is brain dead, comatose, or otherwise incapable of letting it be known if he or she would prefer to live or die.

- Mercy killing.

- Physician-assisted suicide.

- Killing a terminally ill person at his request.

The term euthanasia is used only in senses (6) and (7) in this article. When other people debate about euthanasia, they could well be using it in senses (1) through (5), or with some other definition. To make this distinction clearer, two other definitions of euthanasia follow:

Euthanasia by means

There can be passive, non-aggressive, and aggressive euthanasia.

- Passive euthanasia is withholding common treatments (such as antibiotics, drugs, or surgery) or giving a medication (such as morphine) to relieve pain, knowing that it may also result in death (principle of double effect). Passive euthanasia is currently the most accepted form as it is currently common practice in most hospitals.

- Non-aggressive euthanasia is the practice of withdrawing life support and is more controversial.

- Aggressive euthanasia is using lethal substances or force to bring about death, and is the most controversial means.

James Rachels has challenged both the use and moral significance of that distinction for several reasons:

To begin with a familiar type of situation, a patient who is dying of incurable cancer of the throat is in terrible pain, which can no longer be satisfactorily alleviated. He is certain to die within a few days, even if present treatment is continued, but he does not want to go on living for those days since the pain is unbearable. So he asks the doctor for an end to it, and his family joins in this request. …Suppose the doctor agrees to withhold treatment. …The justification for his doing so is that the patient is in terrible agony, and since he is going to die anyway, it would be wrong to prolong his suffering needlessly. But now notice this. If one simply withholds treatment, it may take the patient longer to die, and so he may suffer more than he would if more direct action were taken and a lethal injection given. This fact provides strong reason for thinking that, once the initial decision not to prolong his agony has been made, active euthanasia is actually preferable to passive euthanasia, rather than the reverse.[1]

Euthanasia by consent

There is also involuntary, non-voluntary, and voluntary euthanasia.

- Involuntary euthanasia is euthanasia against someone’s will and equates to murder. This kind of euthanasia is almost always considered wrong by both sides and is rarely debated.

- Non-voluntary euthanasia is when the person is not competent to or unable to make a decision and it is thus left to a proxy like in the Terri Schiavo case. Terri Schiavo, a Floridian who was believed to have been in a vegetative state since 1990, had her feeding tube removed in 2005. Her husband had won the right to take her off life support, which he claimed she would want but was difficult to confirm as she had no living will. This form is highly controversial, especially because multiple proxies may claim the authority to decide for the patient.

- Voluntary euthanasia is euthanasia with the person’s direct consent, but is still controversial as can be seen by the arguments section below.

Mercy killing

Mercy killing refers to killing someone to put them out of their suffering. The killer may or may not have the informed consent of the person killed. We shall use the term mercy killing only when there is no consent. Legally, mercy killing without consent is usually treated as murder.

Murder

Murder is intentionally killing someone in an unlawful way. There are two kinds of murder:

- The murderer has the informed consent of the person killed.

- The murderer does not have the informed consent of the person killed.

In most parts of the world, types (1) and (2) murder are treated identically. In other parts, type (1) murder is excusable under certain special circumstances, in which case it ceases to be considered murder. Murder is, by definition, unlawful. It is a legal term, not a moral one. Whether euthanasia is murder or not is a simple question for lawyers—"Will you go to jail for doing it or won't you?"

Whether euthanasia should be considered murder or not is a matter for legislators. Whether euthanasia is good or bad is a deep question for the individual citizen. A right to die and a pro life proponent could both agree "euthanasia is murder," meaning one will go to jail if he were caught doing it, but the right to die proponent would add, "but under certain circumstances, it should not be, just as it is not considered murder now in the Netherlands."

History

The term "euthanasia" comes from the Greek words “eu” and “thanatos,” which combined means “good death.” Hippocrates mentions euthanasia in the Hippocratic Oath, which was written between 400 and 300 B.C.E. The original Oath states: “To please no one will I prescribe a deadly drug nor give advice which may cause his death."

Despite this, the ancient Greeks and Romans generally did not believe that life needed to be preserved at any cost and were, in consequence, tolerant of suicide in cases where no relief could be offered to the dying or, in the case of the Stoics and Epicureans, where a person no longer cared for his life.

The English Common Law from the 1300s until today also disapproved of both suicide and assisting suicide. It distinguished a suicide, who was by definition of unsound mind, from a felo-de-se or "evildoer against himself," who had coolly decided to end it all and, thereby, perpetrated an “infamous crime.” Such a person forfeited his entire estate to the crown. Furthermore his corpse was subjected to public indignities, such as being dragged through the streets and hung from the gallows, and was finally consigned to "ignominious burial," and, as the legal scholars put it, the favored method was beneath a crossroads with a stake driven through the body.

Modern history

Since the nineteenth century, euthanasia has sparked intermittent debates and activism in North America and Europe. According to medical historian Ezekiel Emanuel, it was the availability of anesthesia that ushered in the modern era of euthanasia. In 1828, the first known anti-euthanasia law in the United States was passed in the state of New York, with many other localities and states following suit over a period of several years.

Euthanasia societies were formed in England, in 1935, and in the U.S., in 1938, to promote aggressive euthanasia. Although euthanasia legislation did not pass in the U.S. or England, in 1937, doctor-assisted euthanasia was declared legal in Switzerland as long as the person ending the life has nothing to gain. During this period, euthanasia proposals were sometimes mixed with eugenics.

While some proponents focused on voluntary euthanasia for the terminally ill, others expressed interest in involuntary euthanasia for certain eugenic motivations (targeting those such as the mentally "defective"). Meanwhile, during this same era, U.S. court trials tackled cases involving critically ill people who requested physician assistance in dying as well as “mercy killings,” such as by parents of their severely disabled children.[2]

Prior to World War II, the Nazis carried out a controversial and now-condemned euthanasia program. In 1939, Nazis, in what was code named Action T4, involuntarily euthanized children under three who exhibited mental retardation, physical deformity, or other debilitating problems whom they considered "unworthy of life.” This program was later extended to include older children and adults.

Post-War history

Leo Alexander, a judge at the Nuremberg trials after World War II, employed a "slippery slope" argument to suggest that any act of mercy killing inevitably will lead to the mass killings of unwanted persons:

The beginnings at first were a subtle shifting in the basic attitude of the physicians. It started with the acceptance of the attitude, basic in the euthanasia movement, that there is such a thing as life not worthy to be lived. This attitude in its early stages concerned itself merely with the severely and chronically sick. Gradually, the sphere of those to be included in this category was enlarged to encompass the socially unproductive, the ideologically unwanted, the racially unwanted and finally all non-Germans.[3]

Critics of this position point to the fact that there is no relation at all between the Nazi "euthanasia" program and modern debates about euthanasia. The Nazis, after all, used the word "euthanasia" to camouflage mass murder. All victims died involuntarily, and no documented case exists where a terminal patient was voluntarily killed. The program was carried out in the closest of secrecy and under a dictatorship. One of the lessons that we should learn from this experience is that secrecy is not in the public interest.

However, due to outrage over Nazi euthanasia crimes, in the 1940s and 1950s, there was very little public support for euthanasia, especially for any involuntary, eugenics-based proposals. Catholic church leaders, among others, began speaking against euthanasia as a violation of the sanctity of life.

Nevertheless, owing to its principle of double effect, Catholic moral theology did leave room for shortening life with pain-killers and what would could be characterized as passive euthanasia (Papal statements 1956-1957). On the other hand, judges were often lenient in mercy-killing cases.[4]

During this period, prominent proponents of euthanasia included Glanville Williams[5] and clergyman Joseph Fletcher.[6] By the 1960s, advocacy for a right-to-die approach to voluntary euthanasia increased.

A key turning point in the debate over voluntary euthanasia (and physician-assisted dying), at least in the United States, was the public furor over the case of Karen Ann Quinlan. In 1975, Karen Ann Quinlan, for reasons still unknown, ceased breathing for several minutes. Failing to respond to mouth-to mouth resuscitation by friends she was taken by ambulance to a hospital in New Jersey. Physicians who examined her described her as being in "a chronic, persistent, vegetative state," and later it was judged that no form of treatment could restore her to cognitive life. Her father asked to be appointed her legal guardian with the expressed purpose of discontinuing the respirator which kept Karen alive. After some delay, the Supreme Court of New Jersey granted the request. The respirator was turned off. Karen Ann Quinlan remained alive but comatose until June 11, 1985, when she died at the age of 31.

In 1990, Jack Kevorkian, a Michigan physician, became infamous for encouraging and assisting people in committing suicide which resulted in a Michigan law against the practice in 1992. Kevorkian was later tried and convicted in 1999, for a murder displayed on television. Meanwhile in 1990, the Supreme Court approved the use of non-aggressive euthanasia.

Influence of religious policies

Suicide or attempted suicide, in most states, is no longer a criminal offense. This demonstrates that there is consent among the states to self determination, however, the majority of the states postulate that assisting in suicide is illegal and punishable even when there is written consent from the individual. Let us now see how individual religions regard the complex subject of euthanasia.

Christian religions

Roman Catholic policy

In Catholic medical ethics, official pronouncements tend to strongly oppose active euthanasia, whether voluntary or not. Nevertheless, Catholic moral theology does allow dying to proceed without medical interventions that would be considered "extraordinary" or "disproportionate." The most important official Catholic statement is the Declaration on Euthanasia.[7]

The Catholic policy rests on several core principles of Catholic medical ethics, including the sanctity of human life, the dignity of the human person, concomitant human rights, and due proportionality in casuistic remedies.[7]

Protestant policies

Protestant denominations vary widely on their approach to euthanasia and physician assisted death. Since the 1970s, Evangelical churches have worked with Roman Catholics on a sanctity of life approach, though the Evangelicals may be adopting a more exceptionless opposition. While liberal Protestant denominations have largely eschewed euthanasia, many individual advocates (such as Joseph Fletcher) and euthanasia society activists have been Protestant clergy and laity. As physician assisted dying has obtained greater legal support, some liberal Protestant denominations have offered religious arguments and support for limited forms of euthanasia.

Jewish policies

Not unlike the trend among Protestants, Jewish movements have become divided over euthanasia since the 1970s. Generally, Orthodox Jewish thinkers oppose voluntary euthanasia, often vigorously, though there is some backing for voluntary passive euthanasia in limited circumstances (Daniel Sinclair, Moshe Tendler, Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Moshe Feinstein). Likewise, within the Conservative Judaism movement, there has been increasing support for passive euthanasia. In Reform Judaism responsa, the preponderance of anti-euthanasia sentiment has shifted in recent years to increasing support for certain passive euthanasia.

Non-Abrahamic religions

Buddhism and Hinduism

In Theravada Buddhism, a monk can be expelled for praising the advantages of death, even if they simply describe the miseries of life or the bliss of the afterlife in a way that might inspire a person to commit suicide or pine away to death. In caring for the terminally ill, one is forbidden to treat a patient so as to bring on death faster than would occur if the disease were allowed to run its natural course.

In Hinduism, the Law of Karma states that any bad action happening in one lifetime will be reflected in the next. Euthanasia could be seen as murder, and releasing the Atman before its time. However, when a body is in a vegetative state, and with no quality of life, it could be seen that the Atman has already left. When avatars come down to earth they normally do so to help out humankind. Since they have already attained Moksha they choose when they want to leave.

Islam

Muslims are against euthanasia. They believe that all human life is sacred because it is given by Allah, and that Allah chooses how long each person will live. Human beings should not interfere in this. Euthanasia and suicide are not included among the reasons allowed for killing in Islam.

"Do not take life, which Allah made sacred, other than in the course of justice" (Qur'an 17:33).

"If anyone kills a person—unless it be for murder or spreading mischief in the land—it would be as if he killed the whole people" (Qur'an 5:32).

The Prophet said: "Amongst the nations before you there was a man who got a wound, and growing impatient (with its pain), he took a knife and cut his hand with it and the blood did not stop till he died. Allah said, 'My Slave hurried to bring death upon himself so I have forbidden him (to enter) Paradise'" (Sahih Bukhari 4.56.669).

Senicide

Senicide, or geronticide, is the killing of the elderly, or their abandonment to death. Various justifications for the practice have been used, including that it was mercy killing that prevented old people from extended suffering; or that it was done for the good of the whole, as the old people were no longer useful and were a burden on their family or the society, for example when the food supply was too low to feed everyone. Such practices have been recorded in many different cultures in history, although some cases may be more myth than reality.

Cultures practicing senicide in history

The case of institutionalized senicide occurring in Ancient Rome comes from a proverb stating that 60-year-olds were to be thrown from the bridge (sexagenarios de ponte deici oportet), and a ceremony in which effigies were thrown off in place of actual living persons.[8] The most comprehensive explanation of the tradition comes from Festus writing in the fourth century CE who provides several different beliefs of the origin of the act, including human sacrifice by ancient Roman natives, a Herculean association, and the notion that older men should not vote because they no longer provided a duty to the state.[9] This idea to throw older men into the river probably coincides with the last explanation given by Festus. That is, younger men did not want the older generations to overshadow their wishes and ambitions and, therefore, suggested that the old men should be thrown off the bridge, where voting took place, and not be allowed to vote.

Parkin provides a number of cases of senicide which the people of antiquity believed happened.[9] Of these cases, only two of them occurred in Greek society; another took place in Roman society, while the rest happened in other cultures. One example that Parkin provides is of the island of Keos in the Aegean Sea. Although many different variations of the Keian story exist, the legendary practice may have begun when the Athenians besieged the island. In an attempt to preserve the food supply, the Keians voted for all people over 60 years of age to commit suicide by drinking hemlock.[9] The other case of Roman senicide occurred on the island of Sardinia, where human sacrifices of 70-years-old fathers were made by their sons to the titan Cronus.

Scythian tribes were reputed to practice senicide. According to Herodotus, the Massagetae:

Though they fix no certain term to life, yet when a man is very old all his family meet together and kill him, with beasts of the flock besides, then boil the flesh and feast on it. This is held to be the happiest death; when a man dies of an illness, they do not eat him, but bury him in the earth, and lament that he did not live to be killed.[9]

According to Aelian, The Derbiccae (a tribe, apparently of Scythian origin, settled in Margiana, on the left bank of the Oxus) kill those who are seventy years of age. They sacrifice the men and strangle the women.[10]

Pomponius Mela commented on people of India:

Some kill their neighbors and parents, in manner of sacrifice, before they pine away with age and sickness, and think it not only lawful, but also godly, to eat the bowels of them when they have killed them. But if they be attacked with old age or sickness, they get them out of all company into the wilderness, and there without sorrowing for the matter, abide the end of their life. The wiser sort of them, which are trained up in the profession and study of wisdom, linger not for death, but hasten it, by throwing themselves into the fire, which is counted a glory.[11]

Herodotus says of the Padeans of India:

Other Indians, to the east of these, are nomads and eat raw flesh; they are called Padaei. It is said to be their custom that when anyone of their fellows, whether man or woman, is sick, a man's closest friends kill him, saying that if wasted by disease he will be lost to them as meat; though he denies that he is sick, they will not believe him, but kill and eat him. When a woman is sick, she is put to death like the men by the women who are her close acquaintances. As for one that has come to old age, they sacrifice him and feast on his flesh; but not many reach this reckoning, for before that everyone who falls ill they kill.[11]

In earlier times Inuit would leave their elderly on the ice to die but it was rare, except during famines.[12] When food is not sufficient, the elderly are the least likely to survive. In the extreme case of famine, the Inuit fully understood that, if there was to be any hope of obtaining more food, a hunter was necessarily the one to feed on whatever food was left.

While such a situation would lead to some loss of life, the elderly were not the first choice. In a culture with an oral history, elders are the keepers of communal knowledge, effectively the community library. Because they are of extreme value as the repository of knowledge, there are cultural taboos against sacrificing elders.[13]

Given the importance that Eskimos attached to the aged, it is surprising that so many Westerners believe that they systematically eliminated elderly people as soon as they became incapable of performing the duties related to hunting or sewing.[14]

However, a common response to desperate conditions and the threat of starvation was infanticide. A mother might abandon an infant in hopes that someone less desperate might find and adopt the child before the cold or animals killed it. The belief that the Inuit regularly resorted to infanticide may be due in part to studies done by Asen Balikci.[15] Other recent research has noted that:

While there is little disagreement that there were examples of infanticide in Inuit communities, it is presently not known the depth and breadth of these incidents. The research is neither complete nor conclusive to allow for a determination of whether infanticide was a rare or a widely practiced event.[16]

Senicide myths

In Scandinavian folklore, the ättestupa is a cliff where elderly people were said to leap, or be thrown, to death. According to legend, this was done when old people were unable to support themselves or assist in a household. The name supposedly denotes sites where ritual senicide took place during pagan Nordic prehistoric times:

In the “collective memory” of the treatment of old people in bygone days, the idea of the “suicidal precipice” (Swedish ättestupa) plays a major role: old people in pagan times were thought to have fallen to their deaths off a cliff, whether voluntarily jumping or being pushed.[17]

Ubasute (姥捨, 'abandoning an old woman'), was a custom allegedly performed in Japan in the distant past, whereby an infirm or elderly relative was carried to a mountain, or some other remote, desolate place, and left there to die.[18] Most have concluded, however, that ubasute "is the subject of legend, but ... does not seem ever to have been a common custom."[19]

Lapot is a mythical Serbian practice of disposing of one's parents, or other elderly family members, once they become a financial burden on the family. According to Georgevitch (Đorđević), writing in 1918 about the eastern highlands of Serbia, in the region of Zaječar, the killing was carried out with an axe or stick, and the entire village was invited to attend. In some places corn mush was put on the head of the victim to make it seem as if the corn, not the family, was the killer.[20]

Georgevitch suggests that this legend may have originated in tales surrounding the Roman occupation of local forts.

The Romans ... were very bellicose people. Their leader ordered all the holders of the fort up to forty years of age to be active fighters, from forty to fifty to be guards of the fort, and after fifty to be killed, because they have no military value. Since that period the old men were killed.[20]

However, Jovanović argued that this interpretation confused myth with reality. The well-known story of a grandson who hid his grandfather to protect him from lapot after a bad harvest, then bringing him back to the village when the old man's wisdom had shown a way to survive, was the basis for establishing that the old should be respected for their knowledge and wise counsel.[21]

Contemporary occurrences

In the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, senicide – known locally as thalaikoothal – is said to occur dozens or perhaps hundreds of times each year despite being illegal.[22]

However it may be disguised as a ritual, thalaikoothal is actually a crude practice of killing the elderly because the family can no longer afford to take care of them. In India, only passive euthanasia (withholding common treatments) is legal which means that the killing of aged parents by any of the diverse methods that have become available, such as lethal injections or overdosed on sleeping pills, is illegal.

The practice is justified as a kindness:

What else can they do if they see their parents suffering? At least they are offering their parents a peaceful death. ... It is an act of dignity because living like a piece of log for years is disrespectful for the elderly themselves, more than for us. The elderly choose to be offered thalaikoothal.[23]

General conclusions

The debate in the ethics literature on euthanasia is just as divided as the debate on physician-assisted suicide, perhaps more so. "Slippery-slope" arguments are often made, supported by claims about abuse of voluntary euthanasia in the Netherlands.

Arguments against it are based on the integrity of medicine as a profession. In response, autonomy and quality-of-life-base arguments are made in support of euthanasia, underscored by claims that when the only way to relieve a dying patient's pain or suffering is terminal sedation with loss of consciousness, death is a preferable alternative—an argument also made in support of physician-assisted suicide.

To summarize, there may be some circumstances when euthanasia is the morally correct action, however, one should also understand that there are real concerns about legalizing euthanasia because of fear of misuse and/or overuse and the fear of the slippery slope leading to a loss of respect for the value of life. What is needed are improvements in research, the best palliative care available, and above all, people should, perhaps, at this time begin modifying homicide laws to include motivational factors as a legitimate defense.

Just as homicide is acceptable in cases of self-defense, it could be considered acceptable if the motive is mercy. Obviously, strict parameters would have to be established that would include patients' request and approval, or, in the case of incompetent patients, advance directives in the form of a living will or family and court approval.

Mirroring this attitude, there are countries and/or states—such as Albania (in 1999), Australia (1995), Belgium (2002), The Netherlands (2002), the U.S. state of Oregon, and Switzerland (1942)—that, in one way or other, have legalized euthanasia; in the case of Switzerland, a long time ago.

In others, such as UK and U.S., discussion has moved toward ending its illegality. On November 5, 2006, Britain's Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists submitted a proposal to the Nuffield Council on Bioethics calling for consideration of permitting the euthanasia of disabled newborns. The report did not address the current illegality of euthanasia in the United Kingdom, but rather calls for reconsideration of its viability as a legitimate medical practice. The United States Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of assisted suicide, in 2000, recognizing individual interests and deciding how, rather than whether, they will die.

Perhaps a fitting conclusion of the subject could be the Japanese suggestion of the Law governing euthanasia:

- In the case of "passive euthanasia," three conditions must be met:

- The patient must be suffering from an incurable disease, and in the final stages of the disease from which he/she is unlikely to make a recovery.

- The patient must give express consent to stopping treatment, and this consent must be obtained and preserved prior to death. If the patient is not able to give clear consent, their consent may be determined from a pre-written document such as a living will or the testimony of the family.

- The patient may be passively euthanized by stopping medical treatment, chemotherapy, dialysis, artificial respiration, blood transfusion, IV drip, and so forth.

- For "active euthanasia," four conditions must be met:

- The patient must be suffering from unbearable physical pain.

- Death must be inevitable and drawing near.

- The patient must give consent. (Unlike passive euthanasia, living wills and family consent will not suffice.)

- The physician must have (ineffectively) exhausted all other measures of pain relief.

Notes

- ↑ James Rachels, The End of Life: Euthanasia and Morality (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0192860705).

- ↑ Yale Kamisar, “Some Non-religious Views against Proposed 'Mercy-killing' Legislation” in Death, Dying, and Euthanasia edited by Dennis J. Horan and David Mall. (Praeger, 1980, ISBN 978-0313270925).

- ↑ Peter Singer, Writings on an Ethical Life (Ecco, 2000, ISBN 978-0060198381).

- ↑ Derek Humphry and Ann Wickett, The Right to Die: Understanding Euthanasia (Carol Publishing Company, 1991, ISBN 978-0960603091).

- ↑ Dennis J. Baker and Jeremy Horder (eds), The Sanctity of Life and the Criminal Law: The Legacy of Glanville Williams (Cambridge University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1107536241).

- ↑ Joseph F. Fletcher, Morals and Medicine: The Moral Problems of the Patient's Right to know the Truth, Contraception, Artificial Insemination, Sterilization, Euthanasia (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1954. ISBN 978-0691072340).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sacred congregation for the doctrine of the faith. The Declaration on Euthanasia. The Vatican, 1980. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ↑ Kenneth Quinn, Catullus: The Poems (Bristol Classical Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1853994975).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Tim G. Parkin, Old Age in the Roman World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0801871283).

- ↑ Jeffrey Henderson, Aelian: Historical Miscellany Book IV: Chapter 3 Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Michael Gilleland, Senicide, Part I Laudator Temporis Acti, June 25, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ↑ Wendell H. Oswalt, Eskimos and Explorers (University of Nebraska Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0803286139).

- ↑ Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley, A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit (Waveland Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1577663843).

- ↑ Ernest S. Burch, The Eskimos (University of Oklahoma Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0806121260).

- ↑ Asen Balikci, The Netsilik Eskimo (Waveland Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0881334357)