Earth Day

Earth Day is an annual event celebrated around the world on April 22 to demonstrate support for environmental protection and to promote awareness of environmental issues such as recycling and renewable energy. Initiated in 1970, based on a proposal by peace activist John McConnell to the United Nations and by Senator Gaylord Nelson's environmental "teach-in," Earth Day is now celebrated by one billion people and includes events coordinated globally by the Earth Day Network in more than 190 countries.

Earth Day grew out of the recognition by young people that the earth is a precious resource, essential for human survival, and that it was being badly mistreated and polluted due to people's irresponsible actions. Activities that raise awareness of the need to care for our environment are an important foundation to assure that human beings will exercise good stewardship over all of nature.

Name

According to the founder of Earth Day, Senator Gaylord Nelson from Wisconsin, the moniker "Earth Day" was "an obvious and logical" name suggested by several people, including specialists in the field of public relations.[1] One of these specialists, Julian Koenig, who was on Nelson's organizing committee in 1969, said that the idea came to him by the coincidence of his birthday with the day selected, April 22; "Earth Day" rhyming with "birthday," the connection seemed natural.[2] Other names circulated during preparations—Nelson himself continued to call it the National Environment Teach-In, but national coordinator Denis Hayes used the term "Earth Day" in his communications and press coverage of the event used this name.

History

Growing eco-activism

The 1960s had been a very dynamic period for ecology in the US. Pre-1960 grassroots activism against DDT in Nassau County, New York, and widespread opposition to open-air nuclear weapons tests with their global nuclear fallout, had inspired Rachel Carson to write her influential bestseller, Silent Spring in 1962.[3]

In 1968, Morton Hilbert and the U.S. Public Health Service organized the Human Ecology Symposium, an environmental conference for students to hear from scientists about the effects of environmental degradation on human health.

1969 Santa Barbara oil spill

On January 28, 1969, a well drilled by Union Oil Platform A off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, blew out. More than three million gallons of oil spewed, killing more than 10,000 seabirds, dolphins, seals, and sea lions. As a reaction to this disaster, activists were mobilized to create environmental regulation, environmental education, and what would become Earth Day. Among the proponents of Earth Day were the people in the front lines of fighting this disaster, Selma Rubin, Marc McGinnes, and Bud Bottoms, founder of Get Oil Out.[4] Denis Hayes said that Senator Gaylord Nelson from Wisconsin was inspired to create Earth Day upon seeing Santa Barbara Channel 800 square-mile oil slick from an airplane.[5]

Santa Barbara's Environmental Rights Day 1970

On the first anniversary of the oil blowout, January 28, 1970, Environmental Rights Day was celebrated, where the Declaration of Environmental Rights was read. It had been written by Rod Nash during a boat trip across the Santa Barbara Channel while carrying a copy of Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence.[4] The organizers of Environmental Rights Day, led by Marc McGinnes, had been working closely over a period of several months with Congressman Pete McCloskey (R-CA) to consult on the creation of the National Environmental Policy Act, the first of many new environmental protection laws sparked by the national outcry about the blowout/oil spill and on the Declaration of Environmental Rights. Both McCloskey (Earth Day co-chair with Senator Gaylord Nelson) and Earth Day organizer Denis Hayes, along with Senator Alan Cranston, Paul Ehrlich, David Brower, and other prominent leaders, endorsed the Declaration and spoke about it at the Environmental Rights Day conference. According to Francis Sarguis, "the conference was sort of like the baptism for the movement." According to Hayes, this was the first giant crowd he spoke to that "felt passionately, I mean really passionately, about environmental issues. ... I thought, we might have ourselves a real movement."[4]

Equinox Earth Day (March 20)

The equinoctial Earth Day is celebrated on the March equinox (around March 20) to mark the arrival of astronomical spring in the Northern Hemisphere, and of astronomical autumn in the Southern Hemisphere. John McConnell first introduced the idea of a global holiday on this day at the 1969 UNESCO Conference on the Environment. The first Earth Day proclamation was issued by San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto on March 21, 1970. Celebrations were held in various cities, such as San Francisco and in Davis, California with a multi-day street party.

UN Secretary-General U Thant supported McConnell's global initiative to celebrate this annual event; and on February 26, 1971, he signed a proclamation to that effect, saying:

May there be only peaceful and cheerful Earth Days to come for our beautiful Spaceship Earth as it continues to spin and circle in frigid space with its warm and fragile cargo of animate life.[6]

United Nations secretary-general Kurt Waldheim observed Earth Day with similar ceremonies on the March equinox in 1972, and the United Nations Earth Day ceremony has continued each year since on the day of the March equinox (the United Nations also works with organizers of the April 22 global event). Margaret Mead added her support for the equinox Earth Day, and in 1978 declared:

Earth Day is the first holy day which transcends all national borders, yet preserves all geographical integrities, spans mountains and oceans and time belts, and yet brings people all over the world into one resonating accord, is devoted to the preservation of the harmony in nature and yet draws upon the triumphs of technology, the measurement of time, and instantaneous communication through space.

Earth Day draws on astronomical phenomena in a new way – which is also the most ancient way – by using the Vernal Equinox, the time when the Sun crosses the equator making the length of night and day equal in all parts of the Earth. To this point in the annual calendar, EARTH DAY attaches no local or divisive set of symbols, no statement of the truth or superiority of one way of life over another. But the selection of the March Equinox makes planetary observance of a shared event possible, and a flag which shows the Earth, as seen from space, appropriate.[7]

At the moment of the equinox, it is traditional to observe Earth Day by ringing the Japanese Peace Bell, which was donated by Japan to the United Nations. This bell is also rung at the observance of the Spring Equinox for the Southern Hemisphere on September 21, the International Day of Peace.[8]

Earth Day 1970

In 1969, a month after peace activist John McConnell proposed a day to honor the Earth and the concept of peace at a UNESCO Conference in San Francisco, United States Senator Gaylord Nelson proposed the idea of holding a nationwide environmental teach-in on April 22, 1970. Nelson was later awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Bill Clinton in recognition of his work, on the 25th anniversary of the first Earth Day.[9]

Project Survival, an early environmentalism-awareness education event, was held at Northwestern University on January 23, 1970. This was the first of several events held at university campuses across the United States in the lead-up to the first Earth Day.

Nelson hired a young activist, Denis Hayes, to be the National Coordinator and in the winter of 1969–1970, a group of students met at Columbia University to hear Hayes talk about his plans for Earth Day, as it was now called. Among the group were Fred Kent, Pete Grannis, and Kristin and William Hubbard. This group agreed to head up the New York City activities within the national movement. Fred Kent took the lead in renting an office and recruiting volunteers. The big break came when Mayor John Lindsay agreed to shut down Fifth Avenue for the event. Mayor Lindsay also made Central Park available for Earth Day. In Union Square, the New York Times estimated crowds of up to 20,000 people at any given time and, perhaps, more than 100,000 over the course of the day.[10] Since Manhattan was also the home of NBC, CBS, ABC, The New York Times, TIME, and Newsweek, it provided the best possible anchor for national coverage from their reporters throughout the country.

Under the leadership of labor leader Walter Reuther, the United Auto Workers was the most instrumental outside financial and operational supporter of the first Earth Day.[11][12] Under Reuther's leadership, the UAW also funded telephone capabilities so that the organizers could communicate and coordinate with each other from all across the United States.[12] The UAW also financed, printed, and mailed all of the literature and other materials for the first Earth Day and mobilized its members to participate in the public demonstrations across the country.[11] According to Denis Hayes, "The UAW was by far the largest contributor to the first Earth Day" and "Without the UAW, the first Earth Day would have likely flopped!"[11] Hayes further said, "Walter’s presence at our first press conference utterly changed the dynamics of the coverage—we had instant credibility."[13]

The first Earth Day celebrations took place in two thousand colleges and universities, roughly ten thousand primary and secondary schools, and hundreds of communities across the United States. More importantly, it "brought 20 million Americans out into the spring sunshine for peaceful demonstrations in favor of environmental reform."[14]

U.S. Senator Edmund Muskie was the keynote speaker on Earth Day in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. Other notable attendees included consumer protection activist and presidential candidate Ralph Nader; landscape architect Ian McHarg; Nobel prize-winning Harvard biochemist George Wald; U.S. Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott; and poet Allen Ginsberg.

Significance of April 22

Nelson chose the date to maximize participation on college campuses for what he conceived as an "environmental teach-in." He determined the week of April 19–25 was the best bet as it did not fall during exams or spring breaks. Moreover, it did not conflict with religious holidays such as Easter or Passover, and was late enough in spring to have decent weather. More students were likely to be in class, and there would be less competition with other mid-week events—so he chose Wednesday, April 22. The day also fell after the anniversary of the birth of noted conservationist John Muir. The National Park Service, John Muir National Historic Site, has a celebration every year in April, called Birthday-Earth Day, in recognition of Earth Day and John Muir's contribution to the collective consciousness of environmentalism and conservation.[15]

Unbeknownst to Nelson,[16] April 22, 1970, was coincidentally the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Lenin, when translated to the Gregorian calendar (which the Soviets adopted in 1918). Time reported that some suspected the date was not a coincidence, but a clue that the event was "a Communist trick," and quoted a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution as saying, "subversive elements plan to make American children live in an environment that is good for them."[17] J. Edgar Hoover, director of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, may have found the Lenin connection intriguing; it was alleged the FBI conducted surveillance at the 1970 demonstrations.[18] The idea that the date was chosen to celebrate Lenin's centenary still persists in some quarters,[19] an idea borne out by the similarity with the subbotnik instituted by Lenin in 1920 as days on which people would have to do community service, which typically consisted in removing rubbish from public property and collecting recyclable material. At the height of its power the Soviet Union established a nationwide subbotnik to be celebrated on Lenin's birthday, April 22, which had been proclaimed a national holiday celebrating communism by Nikita Khrushchev in 1955.

Earth Day 1990 to 1999

The first Earth Day was focused on the United States. In 1990, Denis Hayes, the original national coordinator in 1970, took it international.[20] Mobilizing 200 million people in 141 countries and lifting the status of environmental issues onto the world stage, Earth Day activities in 1990 gave a huge boost to recycling efforts worldwide and helped pave the way for the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. Unlike the first Earth Day in 1970, this 20th Anniversary was waged with stronger marketing tools, greater access to television and radio, and multi-million-dollar budgets.[21]

Two separate groups formed to sponsor Earth Day events in 1990: The Earth Day 20 Foundation, assembled by Edward Furia (Project Director of Earth Week in 1970), and Earth Day 1990, assembled by Denis Hayes (National Coordinator for Earth Day 1970). Senator Gaylord Nelson was honorary chairman for both groups. Due to disagreements, the two did not combine forces and work together. Among the disagreements, key Earth Day 20 Foundation organizers were critical of Earth Day 1990 for including on their board Hewlett-Packard, a company that at the time was the second-biggest emitter of chlorofluorocarbons in Silicon Valley and refused to switch to alternative solvents.[21] In terms of marketing, Earth Day 20 had a grassroots approach to organizing and relied largely on locally based groups like the National Toxics Campaign, a Boston-based coalition of 1,000 local groups concerned with industrial pollution. Earth Day 1990 employed strategies including focus group testing, direct mail fund raising, and email marketing.[21]

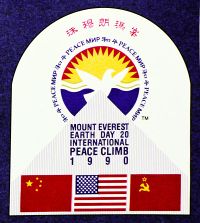

The Earth Day 20 Foundation highlighted its April 22 activities in George, Washington, near the Columbia River with a live satellite phone call with members of the historic Earth Day 20 International Peace Climb who called from their base camp on Mount Everest to pledge their support for world peace and attention to environmental issues.[22] The Earth Day 20 International Peace Climb was led by Jim Whittaker, the first American to summit Everest (many years earlier), and marked the first time in history that mountaineers from the United States, Soviet Union, and China had roped together to climb a mountain, let alone Mount Everest. The group also collected more than two tons of trash (transported down the mountain by support groups along the way) that had been left behind on Mount Everest from previous climbing expeditions.

To turn Earth Day into a sustainable annual event rather than one that occurred every 10 years, Nelson and Bruce Anderson, New Hampshire's lead organizers in 1990, formed Earth Day USA. Building on the momentum created by thousands of community organizers around the world, Earth Day USA coordinated the next five Earth Day celebrations through 1995, including the launch of EarthDay.org. Following the 25th Anniversary in 1995, the coordination baton was handed to the international Earth Day Network.

As the millennium approached, Hayes agreed to spearhead another campaign, this time focusing on global warming and pushing for clean energy. The April 22 Earth Day in 2000 combined the big-picture feistiness of the first Earth Day with the international grassroots activism of Earth Day 1990. For 2000, Earth Day had the internet to help link activists around the world. By the time April 22 came around, 5,000 environmental groups around the world were on board reaching out to hundreds of millions of people in a record 184 countries. Events varied: A talking drum chain traveled from village to village in Gabon, Africa, for example, while hundreds of thousands of people gathered on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Earth Day 2000 to 2019

Earth Day 2000 combined the ambitious spirit of the first Earth Day with the international grassroots activism of Earth Day 1990. This was the first year that Earth Day used the Internet as its principal organizing tool, and it proved invaluable nationally and internationally. Kelly Evans, a professional political organizer, served as executive director of the 2000 campaign. The event ultimately enlisted more than 5,000 environmental groups outside the United States, reaching hundreds of millions of people in a record 183 countries.[23]

For Earth Day in 2014, NASA invited people around the world to step outside to take a "selfie" and share it with the world on social media. NASA created a new view of the earth entirely from those photos. The "Global Selfie" mosaic was built using more than 36,000 photographs of individual faces.

On Earth Day 2016, the landmark Paris Agreement was signed by the United States, China, and some 120 other countries.[24][25] This signing of the Paris Agreement satisfied a key requirement for the entry into force of the historic draft climate protection treaty adopted by consensus of the 195 nations present at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

From Earth Day 2017, the Earth Day Network created tool kits to aid organizations wanting to hold teach-ins "to build a global citizenry fluent in the concept of climate change and inspired by environmental education to act in defense of the planet."[26]

In 2019, Earth Day Network partnered with Keep America Beautiful and National Cleanup Day for the inaugural nationwide Earth Day Clean Up. Cleanups were held in all 50 States, 5 US Territories, 5,300 sites and had more than 500,000 volunteers.[27]

Earth Day 2020

Earth Day 2020 was the 50th Anniversary of Earth Day.[28] The theme for Earth Day 2020 was "climate action," and due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the planned activities were moved online.[29] Notably, a coalition of youth activists organized by the Future Coalition hosted Earth Day Live, a three-day livestream commemorating the 50th anniversary of Earth Day in the United States.[30]

Earth Day is currently observed in over 190 countries, "the largest secular holiday in the world, celebrated by more than a billion people every year."[31]

Notes

- ↑ Earth Day Facts Facts.net. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ William Yardley, Julian Koenig, Who Sold Americans on Beetles and Earth Day, Dies at 93 The New York Times, June 17, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002, ISBN 978-0618249060).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kate Wheeling and Max Ufberg, 'The Ocean Is Boiling': The Complete Oral History of the 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill Pacific Standard, November 7, 2018|. Retrieved November 20, 2020

- ↑ Jonathan Bastian, How the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill sparked Earth Day KCRW, April 21, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ John McConnell, Earth Day: Vision for Peace, Justice, and Earth Care: My Life and Thought at Age 96 (Resource Publications, 2011, ISBN 978-1608995417).

- ↑ Margaret Mead, Earth Day EPA Journal, March 1978. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ About the Peace Bell International Day of Peace. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ The Nelson legacy: for us and our future Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Joseph Lelyveld, Mood Is Joyful as City Gives Its Support The New York Times, April 23, 1970. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Joe Uehlein, Labor and environmentalists have been teaming up since the first Earth Day Grist, April 22, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Olivia B. Waxman, Meet ‘Mr. Earth Day,’ the Man Who Helped Organize the Annual Observance TIME, April 19, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ Melissa Price, The Rumpus Interview with Earth Day Organizer Denis Hayes The Rumpus, April 2, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jack Lewis, The Birth of EPA EPA Journal, November 1985. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ↑ John Muir Birthday–Earth Day Celebration John Muir Association. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Gaylord Nelson, Beyond Earth Day: Fulfilling the Promise (University of Wisconsin Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0299180409).

- ↑ A Memento Mori to the Earth TIME, May 4, 1970. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ John W. Finney, Muski says FBI spied at rallies on 70 Earth Day The New York Times, April 15, 1971. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Alexander Marriott, This Earth Day Celebrate Vladimir Lenin's Birthday! Capitalism Magazine, April 21, 2004. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Denis Hayes The Bullitt Foundation. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Barnaby J. Feder, The Business of Earth Day The New York Times, November 12, 19889. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Earth Day Ellensburg Daily Record, April 23, 1990. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Jeff Gerth, Peaceful, Easy Feeling Imbues 30th Earth Day The New York Times, April 23, 2000. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Here's Why the U.S. and China Are Signing the Historic Paris Agreement on Earth Day The White House, March 31, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ 'Today is an historic day,' says Ban, as 175 countries sign Paris climate accord UN News, April 22, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Kathleen Rogers, Our Toolkits Earth Day Network. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ 500,000 Volunteers Take Part in Earth Day 2019 CleanUp Earth Day Network. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Kimberlee Hurley, Earth Day is 50. We have our work cut out for the next 50 years Sustainability Times, April 22, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ The 50th anniversary of Earth Day was unlike any other Earth Day Network. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Claire Shaffer, 'Earth Day Live' to Celebrate 50th Earth Day With Star-Studded Lineup Rolling Stone, April 16, 2020. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ About Earth Day Network Earth Day Network. Retrieved November 21, 202.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002. ISBN 978-0618249060

- Guion, David M. Before and After the First Earth Day, 1970. Independently Published, 2020. ISBN 979-8639339127

- McCloskey, Paul Pete. The Story Of The First Earth Day 1970: How Grassroots Activism Can Change Our World. Eaglet Books, 2020. ISBN 978-0578657721

- McConnell, John. Earth Day: Vision for Peace, Justice, and Earth Care: My Life and Thought at Age 96. Resource Publications, 2011. ISBN 978-1608995417

- Nelson, Gaylord. Beyond Earth Day: Fulfilling the Promise. University of Wisconsin Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0299180409

- Rome, Adam. The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation. Hill and Wang, 2014. ISBN 978-0865477742

External links

All links retrieved November 21, 2020.

- Earth Day Network – Coordinating worldwide events for Earth Day

- United States Earth Day U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- Earth Day Canada

- Earth Day The History Channel.

- EPA History: Earth Day

- Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies

- Earth Society Foundation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.