Earth lodge

An earth lodge is a semi-subterranean building covered partially or completely with earth, best known from the Native American cultures of the Great Plains and Eastern Woodlands. Most earth lodges were circular in construction with a dome-like roof, often with a central or slightly offset smoke hole at the apex of the dome.

Earth lodges are well-known from the more sedentary tribes of the Plains, such as the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara (also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes) who lived primarily in earth lodges and using tipis as temporary shelter while traveling from their villages or on seasonal bison hunts, but they have also been identified archaeologically among sites of the Mississippian culture in the Eastern United States.

The construction of earth lodges as housing had both practical and spiritual aspects. They provided shelter, with the earth covering acting as insulation, and the supporting posts gave strength to the roofs such that people could gather on top of their houses in good weather. Many aspects of their construction also reflected the beliefs of the people, maintaining a close connection between their lifestyle and their mythology, ensuring the passing on of beliefs to the next generation.

Structure

The earliest earth lodges were rectangular in shape. Later, however, they were all circular in form.[1]

The various Plains Indians tribes all built their earth lodges in a similar fashion. They were typically constructed using a wattle and daub technique with a particularly thick coating of earth. The most common wood used was Cottonwood. This is a wet, soft wood which meant that lodges generally required re-building every six to eight years.

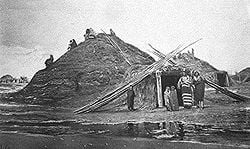

During construction, the workers would dig an area of land a few feet beneath the surface, allowing the entire building to have a floor somewhat below the surrounding ground level. Four (sometimes more) central posts were installed and joined at the top by cross beams. A ring of shorter posts and beams encircled the central frame. A wheel of rafters rested on this outer ring, with the central smoke hole in the center. The dome-like shape of the earth lodge was achieved by the use of angled or carefully bent tree trunks, although hipped roofs were also used on occasion. This construction technique is quite sturdy, and can produce quite large buildings (some as much as 60 feet across) in which more than one family would live, although the size was limited somewhat by the length of available tree trunks.

After a strong layer of sticks or reeds was wrapped through and over the radiating roof timbers, the people often applied a layer of thatch as part of the roof. The structure was then entirely covered in earth. The earth layer and the partially subterranean foundation provided insulation against the extreme temperatures of the Plains.

Symbolism

For some tribes, the earth lodge symbolized their beliefs and mythology. For example, the Hidatsa regarded the earth lodge as a living entity whose spirit lived in the central beams, while for the Mandan the four central posts of the earth lodge represented the four pillars upon which the dome of the sky rests.[1]

For the Pawnee, each lodge "was at the same time the universe and also the womb of a woman, and the household activities represented her reproductive powers."[2] The Pawnee's deities and celestial beings were incorporated in the design of the earth lodge: The presence of the creator god, Tirawa, was experienced through the central smoke hole and the light shining through it; the four central painted poles represented the four major star gods.

Use by Plains Indians

From around 700 C.E., earth lodges were a common dwelling for Native American tribes of the upper Midwest, particularly the semi-sedentary Plains Indians. The Pawnee developed settlements of earth lodges in the central plains of Nebraska and Kansas, while further Northeast the Omaha, Otoe, and Ponca also built earth lodges. In the Dakotas, the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara built their earth lodge villages beside streams that fed the Missouri River.[1]

Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara

The origin of the upper midwest earth lodge is generally attributed to the Mandan tribe, who were a sedentary farming and trading tribe. Later when the Hidatsa came into the area they adopted the earthen structures. The Groundhouse River in Minnesota is thought to have been named for the earth lodges of the Hidatsa who were driven westward by the Sioux.[3] The Arikara, a Caddoan speaking Pawnee tribe, were also builders of earth lodges before they arrived in North Dakota.

Earth lodges were often found alongside tribal farm fields, alternating with tipis (which were used during the nomadic hunting season). A reconstructed earth lodge can be seen at the Glenwood, Iowa Lake Park; an earth-lodge village may be seen at New Town, North Dakota. The village consists of six family-sized earth lodges and one large ceremonial lodge. In addition, a garden area and corrals have been built for authenticity. The park is open to the public and located west of New Town at the Earthlodge Village Site. The family earth lodges are roughly 40 feet (12 m) in diameter. The ceremonial earth lodge is more than 90 feet (27 m) in diameter, the largest such structure in the world. The park is the central point in a rebuilding and cultural renewal effort by the three affiliated tribes of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. This is the only village of its kind to be constructed by the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nations in over 100 years.

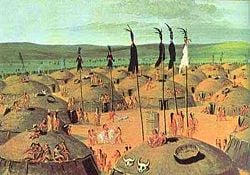

The Mandan historically lived along the banks of the Missouri River and two of its tributaries—the Heart and Knife Rivers—in present-day North and South Dakota. Speakers of Mandan, a Siouan language, the people developed a settled culture in contrast to that of more nomadic tribes in the Great Plains region. One of the most recognizable features of the Mandan was their permanent villages made up of earthen lodges. They established these villages of large, round, earth lodges some 40 feet (12 m) in diameter, surrounding a central plaza. Villages had from a dozen to over 100 lodges, and could have as many as 150 lodges.[4] These structures were a familiar sight to traders and explorers along the banks of the little Missouri, and were found in city clusters of up to a thousand such earthen homes.

Each lodge was circular with a dome-like roof and a square hole at the apex of the dome through which smoke could escape. The exterior was covered with a matting made from reeds and twigs and then covered with hay and earth, which protected the interior from rain, heat and cold. The lodge also featured an extended portico-type structure at the entrance. Generally a windbreak was built on the interior of the lodge, blocking wind and giving privacy to the occupants.[4]

The interior was constructed around four large pillars, upon which crossbeams supported the roof. These lodges were designed, built, and owned by the women of the tribe, and ownership was passed through the female line. Generally 40 feet (12 m) in diameter, they could hold the members of an extended family, up to 30 or 40 people, who slept on raised beds placed around the walls. The fire was in the center. In addition, earth lodges often contained cache pits or root cellar type holes, lined with willow and grasses, within which dried vegetables were stored. There was also a storage area for weapons.[4]

The roofs of the earth lodges were strong enough for people to stand or sit on. Mandan children often played games on the roof while adults sat and talked, or simply dozed in the sun.[5]

Reconstructions of these lodges may be seen at Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park near Mandan, North Dakota, and the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.

Pawnee

The Pawnee generally settled close to the rivers, building their earth lodges on the higher banks. The lodges tended to be oval in shape; the frame was constructed of 10 to 15 posts set some ten feet apart which outlined the floor of the lodge. Lodge size varied based on the number of poles placed in the center of the structure, with most lodges having four, eight, or twelve center poles. A common feature in Pawnee lodges were four painted poles, which represented the four cardinal directions and the four major star gods. A second outer ring of poles outlined the outer circumference of the lodge. Horizontal beams linked the posts together.

The frame was covered first with smaller poles, tied with willow withes. The structure was covered with thatch, then earth. A hole left in the center of the covering served as a combined chimney/smoke hole and skylight. The door of each lodge was placed to the east and the rising sun. A long, low passageway, which helped keep out outside weather, led to an entry room that had an interior buffalo-skin door on a hinge. It could be closed at night and wedged shut. Opposite the door, on the west side of the central room, a buffalo skull with horns was displayed. This was considered great medicine.

Mats were hung on the perimeter of the main room to shield small rooms in the outer ring, which served as sleeping and private spaces. The lodge was semi-subterranean, as the Pawnee recessed the base by digging it approximately three feet below ground level. This insulated the interior from extreme temperatures. Lodges were strong enough to support adults, who routinely sat on them, and the children who played on the top of the structures.[6]

As many as 30-50 people might live in each lodge, and they were usually of related families. A village could consist of as many as 300-500 people and 10-15 households. Each lodge was divided in two (the north and south), and each section had a head who oversaw the daily business. Each section was further subdivided into three duplicate areas, with tasks and responsibilities related to the age of women and girls. The membership of the lodge was quite flexible. The tribe went on buffalo hunts in summer and winter. Upon their return, the inhabitants of a lodge would often move into another lodge, although they generally remained within the village.

Omaha

During most of the year Omaha Indians lived in earth lodges, ingenious structures with a timber frame and a thick soil covering. These earth lodges were as large as 60 feet in diameter and might hold several families, including their horses.

Omaha beliefs were symbolized in their dwelling structures. At the center of the lodge was a fireplace that recalled their creation myth. The earth lodge entrance faced east, to catch the rising sun and remind the people of their origin and migration upriver. The circular layout of tribal villages reflected the tribe's beliefs. The tribe was divided into two moieties, Sky and Earth people. Sky people were responsible for the tribe's spiritual needs and Earth people for the tribe's physical welfare. Sky people lived in the north half of the village, the area that symbolized the heavens. Earth people lived in the south half which represented the earth. Within each half of the village, individual clans were carefully located based on their member's tribal duties and relationship to other clans.

As the tribe migrated westward from the Ohio River region, they adopted aspects of the lifestyle of the Plains Indians. The woodland custom of these earth lodges was replaced with easier to build and more practical tipis—tents covered in buffalo hides like those used by the Sioux. Tipis were also used during buffalo hunts away from the villages, and when relocating from one village area to another.

The Mississippian culture

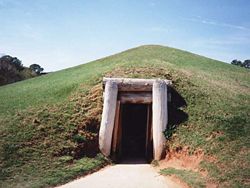

The Mississippian culture was a mound building Native American culture that flourished from approximately 800 C.E. to 1500 C.E. A number of major Mississippian mound centers have identified earth lodges either beneath (preceding) the mound construction or as a mound-top building. Sequential constructions, collapses, and rebuilding of earth lodges seems to be part of the mechanism of construction for certain mounds, including the mound at Town Creek Indian Mound and some of the mounds at Ocmulgee National Monument.

The people of this sophisticated, stratified culture built the complex, massive earthworks that expressed their religious and political system. They built rectangular wooden buildings to house certain religious ceremonies on the platform mounds. The mounds at Ocmulgee were unusual because their distance apart from each other was more than that of other Mississippian complexes. It is believed that this was to provide for public space and residences.

Circular earth lodges were built to serve as places to conduct meetings and important ceremonies. Remains of one of the earth lodges were carbon dated to 1050 C.E. This evidence was the basis for the reconstructed lodge which archeologists later built at the monument center. The interior features a raised-earth platform, shaped like an eagle (a symbol of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex which the people shared with other Mississippian cultures) with a forked-eye motif. Molded seats on the platform were built for the leaders.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Peter Nabokov and Robert Easton, Native American Architecture (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0195066654).

- ↑ Gene Weltfish, The Lost Universe: Pawnee Life and Culture (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0803258716).

- ↑ Newton H. Winchell, The Aborigines of Minnesota (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1911), 67.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Barry H. Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195138771), 336.

- ↑ Carl Waldman, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, ISBN 978-0816062744), 151.

- ↑ James Henry Carleton, The Prairie Logbooks (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0803263147), 66–68.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carleton, James Henry. The Prairie Logbooks. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0803263147

- Hally, David J. (ed.). Ocmulgee Archaeology, 1936-1986. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0820334929

- Meyer, Roy W. The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri: The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras. Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0803209138

- Nabokov, Peter, and Robert Easton. Native American Architecture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 0195066650

- Parks, Douglas Richard, A. Wesley Jones, and Robert C. Hollow. Earth Lodge Tales from the Upper Missouri: Traditional Stories of the Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan. Mary College, 1978. ASIN B000J0FAAG

- Peters, Virginia Bergman. Women of the Earth Lodges: Tribal Life on the Plains. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0806132433

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195138771

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Weltfish, Gene. The Lost Universe: Pawnee Life and Culture. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0803258716

- Winchell, Newton H. The Aborigines of Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1911.

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- Hidatsa Mandan Arikara Earth Lodges

- Earth Lodges Kansas Historical Society

- Ocmulgee National Monument

- Knife River Indian Villages

| |||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.