Tutu, Desmond

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (94 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Approved}}{{images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} |

| − | {{ | + | {{epname|Tutu, Desmond}} |

| − | {{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

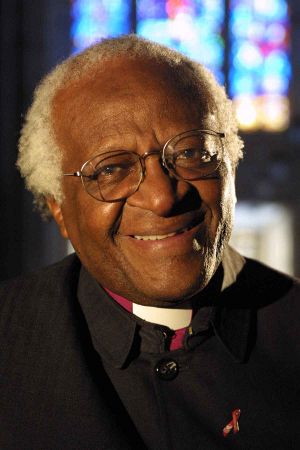

| − | '''Desmond Mpilo Tutu''' ( | + | [[Image:Archbishop-Tutu-medium.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Desmond Tutu]] |

| − | + | '''Desmond Mpilo Tutu''' (October 7, 1931 - December 26, 2021) was a [[South Africa]]n [[cleric]] and activist who rose to worldwide fame during the 1980s as an opponent of [[apartheid]]. Tutu was elected and ordained the first African South African [[Anglicanism|Anglican]] [[Archbishop]] of [[Cape Town]], South Africa, and [[Primate (religion)|primate]] of the Church of the Province of Southern Africa (now the [[Anglican Church of Southern Africa]]). He was awarded the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] in 1984, and was also a recipient of the [[Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism]]. Desmond Tutu was committed to stopping global [[AIDS]] and served as the honorary chairman for the [[Global AIDS Alliance]]. In February 2007, he was awarded the [[Gandhi Peace Prize]] 2005 by [[Abdul Kalam|Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam]], the president of [[India]]. | |

| − | He was generally credited with coining the term | + | {{toc}} |

| + | He was generally credited with coining the term "Rainbow Nation" as a metaphor to describe post-apartheid [[South Africa]] after 1994, under [[African National Congress|ANC]] rule. The expression has since entered mainstream consciousness to describe South Africa's ethnic diversity. | ||

| + | {{readout||right|250px|Desmond Tutu coined the term "Rainbow Nation" to describe the ethnically diverse post-[[apartheid]] [[South Africa]]}} | ||

| + | At the invitation of South Africa's first post-apartheid president, fellow Nobel Peace laureate [[Nelson Mandela]], he chaired the nation's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was charged with healing the wounds of the past with the power to sometimes give amnesty to those who had violated human rights, or who had even committed murder, as part of the task of building a new, equal, just society. | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| − | Desmond Tutu born in [[Klerksdorp]], [[Transvaal]] on 7 | + | Desmond Tutu was born in [[Klerksdorp]], [[Transvaal]], on October 7, 1931. Tutu’s family moved to [[Johannesburg]] when he was 12 years old. Although he wanted to become a [[physician]], his family could not afford the training, and he followed his father's footsteps into [[teaching]]. Tutu studied at the [[Pretoria Bantu Normal College]] from 1951 through 1953, and went on to teach at [[Johannesburg Bantu High School]], where he remained until 1957. He resigned following the passage of the [[Bantu Education Act]], in protest of the poor educational prospects for African South Africans. He continued his studies, this time in [[theology]], and in 1960 was ordained as an [[Anglican]] [[priest]]. He became [[chaplain]] at the [[University of Fort Hare]], a hotbed of dissent and one of the few quality universities for African students in the southern part of Africa. |

| − | Tutu left his post as chaplain and | + | Tutu left his post as chaplain and traveled to [[King's College London]] (1962–1966), where he received his [[Bachelor's degree|Bachelor's]] and [[Master's degree]]s in Theology. He returned to Southern Africa and from 1967 until 1972, used his lectures to highlight the circumstances of the African population. He wrote a letter to [[B.J. Vorster|Prime Minister Vorster]], in which he described the situation in South Africa as a "[[gunpowder|powder barrel]] that can explode at any time." The letter was never answered. From 1970 to 1972, Tutu lectured at the [[National University of Lesotho]]. |

| − | In 1972 Tutu returned to the [[United Kingdom|UK]], where he was appointed vice-director of the Theological Education Fund of the [[World Council of Churches]], at [[Bromley]] in [[Kent]]. He returned to South Africa in 1975 and was appointed Anglican [[Dean (religion)|Dean]] of [[Johannesburg]]—the first African person to hold that position. | + | In 1972, Tutu returned to the [[United Kingdom|UK]], where he was appointed vice-director of the Theological Education Fund of the [[World Council of Churches]], at [[Bromley]] in [[Kent]]. He returned to South Africa in 1975, and was appointed Anglican [[Dean (religion)|Dean]] of [[Johannesburg]]—the first African person to hold that position. |

| − | In 2000 Tutu received a L.H.D. from [[Bates College]], and in 2005, Tutu received an [[honorary degree]] from the [[University of North Florida]], one of the many universities in North America and Europe where he has taught. He visited a school at that time, Twin Lakes Academy Elementary School, and spoke to a class of 3rd graders about his work. | + | In 2000, Tutu received a L.H.D. from [[Bates College]], and in 2005, Tutu received an [[honorary degree]] from the [[University of North Florida]], one of the many universities in North America and Europe where he has taught. He visited a school at that time, Twin Lakes Academy Elementary School, and spoke to a class of 3rd graders about his work. |

| − | In 2005, Tutu was named a [[Doctor of Humane Letters]] at [[Fordham University]] in [[ | + | In 2005, Tutu was named a [[Doctor of Humane Letters]] at [[Fordham University]] in [[New York City]]. He was also awarded Honorary Patronage of the [[University Philosophical Society]] by [[John Hume]], another Honorary Patron of the Society and fellow [[Nobel laureate]]. He was also awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters by [[Berea College]] prior to delivering the commencement address. |

| − | In 2006, Tutu was named a Doctor of Public Service at the [[College of William and Mary]] in Virginia, where he was also the commencement speaker. | + | In 2006, Tutu was named a Doctor of Public Service at the [[College of William and Mary]] in Virginia, where he was also the commencement speaker. He was awarded the [[Light of Truth Award]] along with Belgian artist [[Hergé]] (posthumously for ''[[The Adventures of Tintin|Tintin]]'') by the [[Dalai Lama]] for his contribution towards public understanding of [[Tibet]].<ref>[https://savetibet.org/tutu-and-tintin-to-be-honored-by-dalai-lama/ Tutu and Tintin to be honored by Dalai Lama] ''International Campaign for Tibet'', May 17, 200. Retrieved March 22,December 27, 2021.</ref> |

==Personal life== | ==Personal life== | ||

| − | + | Tutu married [[Leah Nomalizo Tutu]] in 1955. They had four children: Trevor Thamsanqa Tutu, Theresa Thandeka Tutu, Naomi Nontombi Tutu and Mpho Andrea Tutu, all of whom attended the [[Waterford Kamhlaba]] School in [[Swaziland]]. His family supported him fully in his often dangerous campaigns, in which he received many death threats, some of which were communicated to his children. In his ''God Has a Dream'' (2005), he commented that his wife has been "exposed to a fair degree of harassment that would not have happened had she not been my wife," while his children supported him "despite all the harassment and all the death threats."<ref name=GodDream/> | |

| − | + | Desmond Tutu died from prostate cancer at the Oasis Frail Care Centre in Cape Town on December 26, 2021, at the age of 90.<ref>Stanley Uys and Dan van der Vat, [https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/26/the-most-rev-desmond-tutu-obituary The Most Rev Desmond Tutu obituary] ''The Guardian'', December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021.</ref> | |

| + | |||

| + | A Funeral Mass was scheduled for Tutu at St. George's Cathedral, Cape Town, on January 1, 2022. In the days before the funeral, the cathedral rang its bells for 10 minutes each day at noon.<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/27/world/africa/desmond-tutu-mourning.html South Africa Begins a Week of Mourning for Desmond Tutu] ''The New York Times'', December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | ||

==Political work== | ==Political work== | ||

| − | + | The 1976 protests in [[Soweto]], also known as the [[Soweto Riots]], against the government's use of [[Afrikaans]] as a compulsory medium of instruction in black schools, became a massive uprising against apartheid. From then on Tutu supported an economic [[boycott]] of his country. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Desmond Tutu was [[Bishop]] of [[Lesotho]] from 1976 until 1978, when he became [[Secretary-General]] of the [[South African Council of Churches]]. From this position, he was able to continue his work against apartheid with agreement from nearly all churches. Tutu consistently advocated [[reconciliation]] between all parties involved in apartheid through his writings and lectures at home and abroad. Though he was most firm in denouncing South Africa's white-ruled government, Tutu was also harsh in his criticism of the violent tactics of some anti-apartheid groups such as the [[African National Congress]] and denounced [[terrorism]] and [[communism]]. | |

| − | Tutu became the first black person to lead the Anglican Church in [[South Africa]] on 7 | + | Tutu became the first black person to lead the Anglican Church in [[South Africa]] on September 7, 1986. In 1989, he was invited to [[Birmingham, England|Birmingham]], [[England]], [[United Kingdom]], as part of Christian Celebrations marking the city's centenary. Tutu and his wife visited a number of establishments including the [[Nelson Mandela]] School in [[Sparkbrook]], Highgate Baptist Church, where the Bishop spoke to a multi-faith audience. His simple but powerful message that "God loves you" attracted large crowds at various venues in the city. |

After the fall of apartheid, he headed the [[Truth and Reconciliation Commission (South Africa)|Truth and Reconciliation Commission]], for which he was awarded the [[Sydney Peace Prize]] in 1999. | After the fall of apartheid, he headed the [[Truth and Reconciliation Commission (South Africa)|Truth and Reconciliation Commission]], for which he was awarded the [[Sydney Peace Prize]] in 1999. | ||

| − | In 2004, Tutu returned to the UK as Visiting Professor in Post-Conflict Societies at [[King's College London|King's College]] and gave the Commemoration Oration as part of the College's 175th anniversary. He also visited the student union nightclub named "Tutu's" in his | + | In 2004, Tutu returned to the UK as Visiting Professor in Post-Conflict Societies at [[King's College London|King's College]] and gave the Commemoration Oration as part of the College's 175th anniversary. He also visited the student union nightclub named "Tutu's" in his honor, and featuring a bust of his likeness. |

| − | On 17 | + | On March 17, 2004, Tutu visited [[Marymount]] to accept Marymount University's 2004 Ethics Award. |

| − | On 30 | + | On November 30, 2006, Tutu was appointed as the lead to a High-Level Fact-Finding Mission mandated by the [[United Nations Human Rights Council]] into the [[Israel]]i military operations which led to [[Beit Hanoun November 2006 incident|civilian deaths]] in [[Beit Hanoun]]. |

| − | == | + | ==Political views== |

===Homosexuality=== | ===Homosexuality=== | ||

| − | In the debate about [[Anglican views of homosexuality]] | + | In the debate about [[Anglican views of homosexuality]] Tutu opposed Christian discrimination against [[homosexuality]]. Commenting days after the August 5, 2003, election of an openly homosexual man to be a bishop in the [[Episcopal Church in the United States of America]], Tutu said, "In our Church here in South Africa, that doesn't make a difference. We just say that at the moment, we believe that they should remain celibate and we don't see what the fuss is about."<ref>Dinky Mkhize, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2003/08/16/tutu-dismisses-uproar-over-gay-american-bishop/a7002e37-a033-422a-be16-4b8e09d5ebcd/ Tutu Dismisses Uproar Over Gay American Bishop] ''The Washington Post'', August 16, 2003. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Later, Tutu increased his criticism of conservative attitudes to homosexuality within his own church, equating [[homophobia]] with [[racism]] and stated that given the problems that Africa faces he thinks it ludicrous that people should focus so much on what people do in bed with whom. | ||

| + | Others equally devoted to divine and human compassion decry homosexuality as part of prophetic responsibility and calling. The issue remains controversial in religious and human affairs. The call to define a divine ideal in human relations should not be presumed as uncaring or dispassionate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===United Nations=== | ||

| + | Tutu expressed support for the [[West Papua]]n independence movement, criticizing the [[United Nations]]' role in the takeover of West Papua by [[Indonesia]]. Tutu said: "For many years the people of South Africa suffered under the yoke of oppression and apartheid. Many people continue to suffer brutal oppression, where their fundamental dignity as human beings is denied. One such people is the people of West Papua." | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Robert Mugabe=== | ||

| + | Tutu also criticized human rights abuses in [[Zimbabwe]], calling Zimbabwean [[President of Zimbabwe|president]] [[Robert Mugabe]] a "caricature of an African dictator," and criticizing the [[South Africa]]n government's policy of quiet diplomacy towards Zimbabwe. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict=== | ||

| + | Tutu spoke of the significant role [[Jew]]s played in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, and has voiced support for [[Israel|Israel's]] security needs and against tactics of [[suicide attack|suicide bombing]] and incitement to hatred.<ref name="tutu">Desmond Tutu, [https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/apr/29/comment Apartheid in the Holy Land] ''The Guardian'', April 28, 2002. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> Tutu was, nonetheless, an active and prominent proponent of the campaign for [[Economic and political boycotts of Israel|divestment from Israel]],<ref> [https://www.jpost.com/diplomacy-and-politics/desmond-tutu-israel-guilty-of-apartheid-in-treatment-of-palestinians-344874 Desmond Tutu: Israel guilty of apartheid in treatment of Palestinians] ''The Jerusalem Post'', March 10, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> and likened Israel's treatment of [[Palestinian]]s to the treatment of Black South Africans under [[apartheid]].<ref name="tutu"/> Former U.S. President [[Jimmy Carter]] in his ''Palestine: Not Apartheid'' (2007) uses a similar comparison of how Palestinians are being treated in the West Bank and Gaza strip with South Africa's treatment of non-whites during the long years of Apartheid. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Nelson Mandela Foundation lecture=== | ||

| + | After a decade of freedom for [[South Africa]], Archbishop Tutu was honored with the invitation to deliver the annual Nelson Mandela Foundation Lecture. On November 23, 2004, Tutu was given the address entitled, "Look to the Rock from Which You Were Hewn." This lecture, critical of the [[African National Congress|ANC]]-controlled government, stirred a pot of controversy between Tutu and [[Thabo Mbeki]], calling into question "the right to criticize." After the first round of volleys were fired, [[South African Press Association|SAPA]] [[journalist]], [[Ben Maclennan]] reported Tutu's response as: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Thank you Mr President for telling me what you think of me, that I am—a liar with scant regard for the truth, and a charlatan posing with his concern for the poor, the hungry, the oppressed and the voiceless (Ben Maclennan, Sapa, 2004-12-02). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | In February 2006, Desmond Tutu took part in the 9th Assembly of the [[World Council of Churches]], held in [[Porto Alegre]], [[Brazil]]. There he manifested his commitment to [[ecumenism]] and praised the efforts of Christian churches to promote dialogue in order to diminish their differences. For Desmond, "a united church is no optional extra." | |

| − | === | + | ===Beit Hanoun=== |

| + | Desmond Tutu was named to head a United Nations fact-finding mission to the [[Gaza Strip]] town of [[Beit Hanoun]], where, in a [[Beit Hanoun November 2006 incident|November 2006 incident]] the [[Israel Defense Forces]] killed 19 civilians after troops wound up a week-long incursion aimed at curbing [[2006 Israel-Gaza conflict|Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel]] from the town. Tutu planned to travel to the Palestinian territory to "assess the situation of victims, address the needs of survivors and make recommendations on ways and means to protect Palestinian civilians against further Israeli assaults," according to the president of the UN Human Rights Council, Luis Alfonso De Alba.<ref>Jacob Slosberg, [https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/tutu-to-head-un-rights-mission-to-gaza Tutu to head UN rights mission to Gaza] ''The Jerusalem Post'', November 29, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Israeli officials expressed concern that the report would be biased against Israel. Tutu canceled the trip in mid-December, saying that Israel had refused to grant him the necessary travel clearance after more than a week of discussions. A spokesman from the Israeli foreign ministry indicated that no final decision had been made, to which Tutu responded, "At times ''not'' making a decision ''is'' making a decision. We couldn't obviously wait in limbo indefinitely."<ref>[https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2006/12/11/israel-turns-down-tutu-mission Israel ‘turns down’ Tutu mission] ''Al Jazeera'', December 11, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | == | + | ==Quotes by Tutu== |

| − | + | * "When missionaries came to South Africa, we had the land, they had the Bible. Then they told us, 'Let's close our eyes and pray.' When we opened our eyes we saw that we have the Bible, they have the land." | |

| − | + | * "If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality." | |

| − | === | + | ==Ubuntu theology== |

| + | Despite sometimes being regarded as more of a political activist than a Christian leader, theology informed everything that Tutu did. He developed a type of theology based on the African concept of "[[ubuntu]]," which refers to human interdependence. God created us, said Tutu, as a single human family. For him, "social harmony … is the ''summum bonum''—the greatest good." All are related to the whole of "creation" and "stewards" of "all of its glory and physicality."<ref name=GodDream>Desmond Tutu, ''God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time'' (New York: Doubleday, 2004, ISBN 978-0385477840).</ref>. Ubuntu does not say, "I think therefore I am" but "I am human because I belong, I participate, I share." It subverts the idea that success by any means is permitted, such as "succeeding at the expense of others." Ultimate freedom is to be found in a human unity that recognizes no barriers, so that "We can be human only together, black and white, rich and poor, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and Jew."<ref name=GodDream/> Tutu had a warm relationship with leaders from faith communities other than his own. | ||

| − | In | + | ==Legacy== |

| + | In an article published in the ''Ecumenical Review'', B.J. de Klerk described Tutu as, alongside [[Nelson Mandela]], an "icon of reconciliation" and an inspiration to many millions of people around the globe. Tutu, he wrote, "is a man who rejoices in the human spirit. His optimism as a devoted Christian, belief in the triumph of good over evil and the remarkable strength of the human spirit help him to overcome the different struggles in his life."<ref>B.J. De Klerk, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1758-6623.2003.tb00467.x Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu: Living Icons of Reconciliation] ''Ecumenical Review'' 55(4) (October 2003): 322-334. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Despite all his honors, Tutu remained at heart a humble priest and servant. He told of the time, when a passenger on his flight mistook him for Bishop [[Abel Muzorewa]], asking an air hostess to request his autograph: "I tried to look modest, although I was thinking in my heart that there were some people who recognized a good thing when they saw it. As she handed me the book and I took out my pen, she said, 'you are Bishop Muzorewa, aren't you?'." "That certainly," writes Tutu, "helped keep my ego in check."<ref name=GodDream/> | |

| − | + | by the time of [[apartheid]]'s fall, Tutu had attained "worldwide respect" for his "uncompromising stand for justice and reconciliation and his unmatched integrity."<ref name=Gish>Steven D. Gish, ''Desmond Tutu: A Biography'' (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0313328602).</ref> According to Allen, Tutu "made a powerful and unique contribution to publicizing the antiapartheid struggle abroad," particularly in the United States.<ref name=Allen> John Allen, ''Rabble-Rouser for Peace: The Authorized Biography of Desmond Tutu'' (Free Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0743269377).</ref> In the latter country, he was able to rise to prominence as a South African anti-apartheid activist because—unlike Mandela and other members of the ANC—he had no links to the South African Communist Party and thus was more acceptable to Americans amid the Cold War anti-communist sentiment of the period.<ref name=Allen/> | |

| − | + | On the day that the prisoner who became President was released, Mandela said of Tutu, "Here is a man who had inspired an entire nation with his words and his courage, who had revived the people's hope during the darkest of times."<ref>Nelson Mandela, ''Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela'' (Boston: Little Brown & Co, 1995), 678.</ref> | |

| − | + | In the U.S., he was often compared to [[Martin Luther King Jr.]], with the African-American civil rights activist [[Jesse Jackson]] referring to him as "the Martin Luther King of South Africa."<ref> Shirley Du Boulay, ''Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless'' (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1988, ISBN 978-0802836496).</ref> | |

| − | + | After the end of apartheid, Tutu became "perhaps the world's most prominent religious leader advocating gay and lesbian rights."<ref name=Allen/> Ultimately, perhaps Tutu's "greatest legacy" was the fact that he gave "to the world as it entered the twenty-first century an African model for expressing the nature of human community."<ref name=Allen/> | |

| − | + | In a message of condolence upon the news of Tutu's death, [[Queen Elizabeth II]] described Tutu as "a man who tirelessly championed human rights in South Africa and across the world", and that his loss will be felt by the people across the Commonwealth, where "he was held in such high affection and esteem".<ref>[https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-59794470 Desmond Tutu: Queen leads UK tributes to archbishop] ''BBC News'', December 26, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | + | Former United States president [[Barack Obama]] released a statement in part calling him a "universal spirit" and that he was "grounded in the struggle for liberation and justice in his own country, but also concerned with injustice everywhere".<ref>[https://apnews.com/article/africa-cape-town-race-and-ethnicity-racial-injustice-south-africa-687040d1e07ebc9f2c18082f83f3a84a UN chief calls Desmond Tutu 'an inspiration to generations'] ''Associated Press'', December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> President [[Joe Biden]] said that Tutu's legacy will "echo throughout the ages."<ref> Olafimihan Oshin, [https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/587337-bidens-desmond-tutus-legacy-will-echo-throughout-the-ages Bidens: Desmond Tutu's legacy will 'echo throughout the ages'] ''The Hill'', December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> Former presidents [[Jimmy Carter]] and [[Bill Clinton]] also released statements upon his death.<ref>Kevin Shalvey,Ivan Pereira, and Christine Theodorou, [https://abcnews.go.com/International/tutu-remembered-true-humanitarian-dedicated-human-rights/story?id=81943519 Tutu remembered as 'true humanitarian' dedicated to human rights] ''ABC News'', December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021. </ref> | |

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| − | + | The [[Archbishop of Canterbury]], [[Justin Welby]], said in his tribute: "When you were in parts of the world where there was little Anglican presence and people weren't sure what the Anglican church was, it was enough to say "It's the Church that Desmond Tutu belongs to" – a testimony to the international reputation he had and the respect with which he was held."<ref>[https://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/news/news-and-statements/archbishop-canterbury-pays-tribute-archbishop-desmond-tutu Archbishop of Canterbury pays tribute to Archbishop Desmond Tutu] ''The Archbishop of Canterbury'', December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021. </ref> | |

| − | + | [[Pope Francis]] lamented his death and praised Tutu for promoting "racial equality and reconciliation in his native South Africa."<ref>[https://www.vaticannews.va/en/pope/news/2021-12/pope-francis-sends-condolences-on-death-of-archbishop-tutu.html Pope laments death of 'servant of the Gospel' Archbishop Tutu] ''Vatican News'', December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | + | == Honors == | |

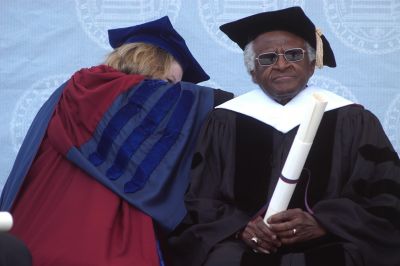

| + | [[File:Desmond Tutu at Penn.jpg|thumb|400px|Tutu at the [[University of Pennsylvania]]]] | ||

| − | + | Tutu gained many international awards and honorary degrees, particularly in South Africa, the United Kingdom, and United States. By 2003, he had approximately 100 honorary degrees.<ref name=Gish/> Many schools and scholarships were named after him. For instance, in 2000 the Munsieville Library in Klerksdorp was renamed the Desmond Tutu Library, and at Fort Hare University, the Desmond Tutu School of Theology was launched in 2002.<ref name=Gish/> | |

| − | |||

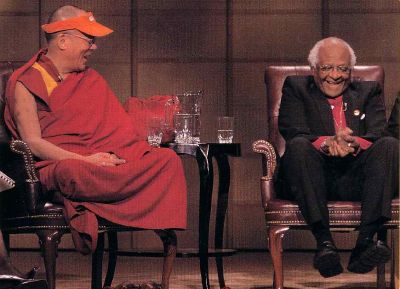

| − | Tutu | + | [[Image:Dalai Lama & Bishop Tutu. Carey Linde.jpg|right|thumb|400px|Nobel Peace Prize Winners the [[Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama|Dalai Lama]] & Bishop Tutu. [[Vancouver]], [[Canada]], 2004. Photo by Carey Linde]] |

| + | On October 16, 1984, Tutu was awarded the [[Nobel Peace Prize]]. The Nobel Committee cited his "role as a unifying leader figure in the campaign to resolve the problem of apartheid in South Africa."<ref>[https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1984/summary/ The Nobel Peace Prize 1984] ''The Nobel Prize''. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> This was seen as a gesture of support for him and The South African Council of Churches which he led at that time. In 1987 Tutu was awarded the [[Pacem in Terris Award]].<ref name=Gish/> | ||

| − | + | In 2003, Tutu received the Golden Plate Award of the [[Academy of Achievement]] presented by Awards Council member [[Coretta Scott King]].<ref>[https://achievement.org/summit/ Summit Overview] ''Academy of Achievement''. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In 2015, Queen Elizabeth II graciously approved Desmond Tutu the honorary British award of [[Order of the Companions of Honour|The Order of the Companions of Honour. (CH)]].<ref>[https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/509363/2015_Honorary_Awards_-_Final.pdf Honorary awards], 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2021. </ref> Queen Elizabeth II appointed Tutu as a Bailiff Grand Cross of the [[Order of Saint John (chartered 1888)|Venerable Order of St. John]] in September 2017.<ref>[https://www.thegazette.co.uk/notice/2871020 Order of St John] ''The Gazette'', September 21, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In 2013 Tutu received the £1.1m ($1.6m) [[Templeton Prize]] for "his life-long work in advancing spiritual principles such as love and forgiveness."<ref>[https://www.templetonprize.org/templeton-prize-winners-2/ Templeton Prize Laureates] ''Templeton Prize''. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | In | ||

| − | + | In 2018 the fossil of a [[Devonian]] [[tetrapod]] was found in [[Grahamstown]] by Rob Gess of the [[Albany Museum]]; this tetrapod was named ''[[Tutusius]] umlambo'' in Tutu's honor.<ref>Steven Lang, [https://www.grocotts.co.za/2018/06/07/grahamstown-scientists-new-fossil-scoop/ Grahamstown scientist's new fossil scoop] ''Grocott's Mail'', June 7, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Publications== |

| + | Tutu authored several collections of sermons and other writings: | ||

| − | + | * ''Desmond Tutu - Crying in the Wilderness Paperback.'' Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1982. ISBN 978-0264671192 | |

| − | Tutu | + | * ''Hope and Suffering: Sermons and Speeches.'' Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1984. ISBN 9780802836144 |

| + | * ''The Words of Desmond Tutu.'' NY: Newmarket Press, 1989. ISBN 9781557040381, with Naomi Tutu | ||

| + | * ''Worshipping Church in Africa.'' Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780822364016 | ||

| + | * ''The Rainbow People of God: The Making of a Peaceful Revolution''. Image, 1996. ISBN 0385483740 | ||

| + | * ''The Essential Desmond Tutu.'' Bellville: Mayibuye Books; Cape Town: D. Philip Publishers 1997. ISBN 9780864863461 | ||

| + | * ''No Future without Forgiveness.'' NY: Doubleday, 1999. ISBN 9780385496896 | ||

| + | * ''The African Prayerbook.'' NY: Hodder & Stoughton Religious Division, 2000. ISBN 978-0340642429 | ||

| + | * ''God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time.'' NY: Doubleday, 2004. ISBN 978-0385477840 | ||

| − | + | Tutu also contributed to numerous books: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * ''Bounty in Bondage: Anglican Church in Southern Africa - Essays in Honour of Edward King, Dean of Cape Town,'' with Frank England, Torguil Paterson, and Torquil Paterson. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1989. ISBN 9780869753835 | |

| + | * ''Resistance Art in South Africa,'' with Sue Williamson, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1990. ISBN 9780312041427 | ||

| + | * ''Freedom from Fear: And Other Writings,'' with Vaclav Havel and Aung San Suu Kyi, BY: Penguion, 1995. ISBN 9780140170894 | ||

| + | * ''Exploring Forgiveness,'' with Robert D. Enright and Joanna North. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998. ISBN 9780299157708 | ||

| + | * ''Love in Chaos: Spiritual Growth and the Search for Peace in Northern Ireland,'' with Mary McAleese NY: Continuum, 1999. ISBN 9780826411372 | ||

| + | * ''At the Side of Torture Suvivors: Treating a Terrible Assault on Human Dignity,'' with Bahman Nirumand, Sepp Graessner and Norbert Gurris. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Pres, 2001. ISBN 9780801866272 | ||

| + | * ''Place of Compassion,'' with Kenneth E. Luckman. Hertford, England: Authors OnLine, 2001. ISBN 9780755200283 | ||

| + | * ''Passion for Peace: Exercising Power Creatively'' with Stuart Rees, Sydney: UNSW Press, 2002. ISBN 9780868407500 | ||

| + | * ''Out of Bounds,'' (New Windmills) with Beverley Naidoo. NY: HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 9780060507992 | ||

| + | * ''Fly, Eagle, Fly!'' with Christopher Gregorowski and Niki Daly. NY: Margaret K. McElderry Books, 2003. ISBN 9780689823985 | ||

| + | * ''Sex, Love and Homophobia: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Lives,'' with Amnesty International, Vanessa Baird and Grayson Perry. London: Amnesty International, 2004. ISBN 9781873328576 | ||

| + | * ''Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation,'' with Gustavo Gutierrez and Marc H. Ellis. 2004. ISBN 9780883443583 | ||

| + | * ''Radical Compassion: The Life and Times of Archbishop Ted Scott'' with Hugh McCullum, Geneva: World Council of Churches, 2004. ISBN 2825414034 | ||

| + | * ''Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another and Other Lessons from the Desert Fathers.'' with Rowan Williams. Boston: New Seeds, 2005. ISBN 978-1590302316 | ||

| + | * ''Mandela,'' with Charlene Smith. Cape Town: Struik Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-1868722068 | ||

| − | + | == Notes == | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | * Allen, John. ''Rabble-Rouser for Peace: The Authorized Biography of Desmond Tutu''. Free Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0743269377 |

| − | * | + | * Du Boulay, Shirley. ''Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless.'' Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1988. ISBN 978-0802836496 |

| − | * Steven D. | + | * Battle, Michael. ''Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology of Desmond Tutu.'' Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0829811582 |

| − | * | + | * Gish, Steven D. ''Desmond Tutu: A Biography.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0313328602 |

| − | * | + | * Hein, David. "Bishop Tutu's Christology." ''Cross Currents'' 34 (1984): 492-499. |

| + | * Hein, David. "Religion and Politics in South Africa." ''Modern Age'' 31 (1987): 21-30. | ||

| + | * Mandela, Nelson. ''Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela.'' Boston: Little Brown & Co, 1995. ISBN 0316548189 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 29, 2024. | |

| − | *[ | + | |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.tutu.org.za/ Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation] |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.tutufoundationuk.org/ Tutu Foundation UK] |

| − | + | *[https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1984/tutu/lecture/ Desmond Tutu Nobel Lecture] ''The Nobel Prize'' | |

*[http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0878379/ IMDB Profile] | *[http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0878379/ IMDB Profile] | ||

| − | + | ||

{{start box}} | {{start box}} | ||

{{succession box|title=[[Anglican Diocese of Cape Town|Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town]]|before=[[Philip Welsford Richmond Russell]]|after=[[Njongonkulu Ndungane]]|years=1986-1996}} | {{succession box|title=[[Anglican Diocese of Cape Town|Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town]]|before=[[Philip Welsford Richmond Russell]]|after=[[Njongonkulu Ndungane]]|years=1986-1996}} | ||

{{end box}} | {{end box}} | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| − | {{Nobel Peace Prize Laureates 1976-2000}} | + | {{Template:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates 1976-2000}} |

| − | + | ---- | |

| − | {{ | + | {{Templeton Prize Laureates}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Nobel Peace Prize Winners]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Politicians and reformers]] | |

| − | |||

| − | [[Category:Nobel Peace Prize | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|117795909}} | {{Credit|117795909}} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:58, 29 January 2024

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (October 7, 1931 - December 26, 2021) was a South African cleric and activist who rose to worldwide fame during the 1980s as an opponent of apartheid. Tutu was elected and ordained the first African South African Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa, and primate of the Church of the Province of Southern Africa (now the Anglican Church of Southern Africa). He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, and was also a recipient of the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism. Desmond Tutu was committed to stopping global AIDS and served as the honorary chairman for the Global AIDS Alliance. In February 2007, he was awarded the Gandhi Peace Prize 2005 by Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, the president of India.

He was generally credited with coining the term "Rainbow Nation" as a metaphor to describe post-apartheid South Africa after 1994, under ANC rule. The expression has since entered mainstream consciousness to describe South Africa's ethnic diversity.

At the invitation of South Africa's first post-apartheid president, fellow Nobel Peace laureate Nelson Mandela, he chaired the nation's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was charged with healing the wounds of the past with the power to sometimes give amnesty to those who had violated human rights, or who had even committed murder, as part of the task of building a new, equal, just society.

Background

Desmond Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, Transvaal, on October 7, 1931. Tutu’s family moved to Johannesburg when he was 12 years old. Although he wanted to become a physician, his family could not afford the training, and he followed his father's footsteps into teaching. Tutu studied at the Pretoria Bantu Normal College from 1951 through 1953, and went on to teach at Johannesburg Bantu High School, where he remained until 1957. He resigned following the passage of the Bantu Education Act, in protest of the poor educational prospects for African South Africans. He continued his studies, this time in theology, and in 1960 was ordained as an Anglican priest. He became chaplain at the University of Fort Hare, a hotbed of dissent and one of the few quality universities for African students in the southern part of Africa.

Tutu left his post as chaplain and traveled to King's College London (1962–1966), where he received his Bachelor's and Master's degrees in Theology. He returned to Southern Africa and from 1967 until 1972, used his lectures to highlight the circumstances of the African population. He wrote a letter to Prime Minister Vorster, in which he described the situation in South Africa as a "powder barrel that can explode at any time." The letter was never answered. From 1970 to 1972, Tutu lectured at the National University of Lesotho.

In 1972, Tutu returned to the UK, where he was appointed vice-director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches, at Bromley in Kent. He returned to South Africa in 1975, and was appointed Anglican Dean of Johannesburg—the first African person to hold that position.

In 2000, Tutu received a L.H.D. from Bates College, and in 2005, Tutu received an honorary degree from the University of North Florida, one of the many universities in North America and Europe where he has taught. He visited a school at that time, Twin Lakes Academy Elementary School, and spoke to a class of 3rd graders about his work.

In 2005, Tutu was named a Doctor of Humane Letters at Fordham University in New York City. He was also awarded Honorary Patronage of the University Philosophical Society by John Hume, another Honorary Patron of the Society and fellow Nobel laureate. He was also awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters by Berea College prior to delivering the commencement address.

In 2006, Tutu was named a Doctor of Public Service at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, where he was also the commencement speaker. He was awarded the Light of Truth Award along with Belgian artist Hergé (posthumously for Tintin) by the Dalai Lama for his contribution towards public understanding of Tibet.[1]

Personal life

Tutu married Leah Nomalizo Tutu in 1955. They had four children: Trevor Thamsanqa Tutu, Theresa Thandeka Tutu, Naomi Nontombi Tutu and Mpho Andrea Tutu, all of whom attended the Waterford Kamhlaba School in Swaziland. His family supported him fully in his often dangerous campaigns, in which he received many death threats, some of which were communicated to his children. In his God Has a Dream (2005), he commented that his wife has been "exposed to a fair degree of harassment that would not have happened had she not been my wife," while his children supported him "despite all the harassment and all the death threats."[2]

Desmond Tutu died from prostate cancer at the Oasis Frail Care Centre in Cape Town on December 26, 2021, at the age of 90.[3]

A Funeral Mass was scheduled for Tutu at St. George's Cathedral, Cape Town, on January 1, 2022. In the days before the funeral, the cathedral rang its bells for 10 minutes each day at noon.[4]

Political work

The 1976 protests in Soweto, also known as the Soweto Riots, against the government's use of Afrikaans as a compulsory medium of instruction in black schools, became a massive uprising against apartheid. From then on Tutu supported an economic boycott of his country.

Desmond Tutu was Bishop of Lesotho from 1976 until 1978, when he became Secretary-General of the South African Council of Churches. From this position, he was able to continue his work against apartheid with agreement from nearly all churches. Tutu consistently advocated reconciliation between all parties involved in apartheid through his writings and lectures at home and abroad. Though he was most firm in denouncing South Africa's white-ruled government, Tutu was also harsh in his criticism of the violent tactics of some anti-apartheid groups such as the African National Congress and denounced terrorism and communism.

Tutu became the first black person to lead the Anglican Church in South Africa on September 7, 1986. In 1989, he was invited to Birmingham, England, United Kingdom, as part of Christian Celebrations marking the city's centenary. Tutu and his wife visited a number of establishments including the Nelson Mandela School in Sparkbrook, Highgate Baptist Church, where the Bishop spoke to a multi-faith audience. His simple but powerful message that "God loves you" attracted large crowds at various venues in the city.

After the fall of apartheid, he headed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for which he was awarded the Sydney Peace Prize in 1999.

In 2004, Tutu returned to the UK as Visiting Professor in Post-Conflict Societies at King's College and gave the Commemoration Oration as part of the College's 175th anniversary. He also visited the student union nightclub named "Tutu's" in his honor, and featuring a bust of his likeness.

On March 17, 2004, Tutu visited Marymount to accept Marymount University's 2004 Ethics Award.

On November 30, 2006, Tutu was appointed as the lead to a High-Level Fact-Finding Mission mandated by the United Nations Human Rights Council into the Israeli military operations which led to civilian deaths in Beit Hanoun.

Political views

Homosexuality

In the debate about Anglican views of homosexuality Tutu opposed Christian discrimination against homosexuality. Commenting days after the August 5, 2003, election of an openly homosexual man to be a bishop in the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, Tutu said, "In our Church here in South Africa, that doesn't make a difference. We just say that at the moment, we believe that they should remain celibate and we don't see what the fuss is about."[5]

Later, Tutu increased his criticism of conservative attitudes to homosexuality within his own church, equating homophobia with racism and stated that given the problems that Africa faces he thinks it ludicrous that people should focus so much on what people do in bed with whom.

Others equally devoted to divine and human compassion decry homosexuality as part of prophetic responsibility and calling. The issue remains controversial in religious and human affairs. The call to define a divine ideal in human relations should not be presumed as uncaring or dispassionate.

United Nations

Tutu expressed support for the West Papuan independence movement, criticizing the United Nations' role in the takeover of West Papua by Indonesia. Tutu said: "For many years the people of South Africa suffered under the yoke of oppression and apartheid. Many people continue to suffer brutal oppression, where their fundamental dignity as human beings is denied. One such people is the people of West Papua."

Robert Mugabe

Tutu also criticized human rights abuses in Zimbabwe, calling Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe a "caricature of an African dictator," and criticizing the South African government's policy of quiet diplomacy towards Zimbabwe.

Views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Tutu spoke of the significant role Jews played in the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, and has voiced support for Israel's security needs and against tactics of suicide bombing and incitement to hatred.[6] Tutu was, nonetheless, an active and prominent proponent of the campaign for divestment from Israel,[7] and likened Israel's treatment of Palestinians to the treatment of Black South Africans under apartheid.[6] Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter in his Palestine: Not Apartheid (2007) uses a similar comparison of how Palestinians are being treated in the West Bank and Gaza strip with South Africa's treatment of non-whites during the long years of Apartheid.

Nelson Mandela Foundation lecture

After a decade of freedom for South Africa, Archbishop Tutu was honored with the invitation to deliver the annual Nelson Mandela Foundation Lecture. On November 23, 2004, Tutu was given the address entitled, "Look to the Rock from Which You Were Hewn." This lecture, critical of the ANC-controlled government, stirred a pot of controversy between Tutu and Thabo Mbeki, calling into question "the right to criticize." After the first round of volleys were fired, SAPA journalist, Ben Maclennan reported Tutu's response as:

Thank you Mr President for telling me what you think of me, that I am—a liar with scant regard for the truth, and a charlatan posing with his concern for the poor, the hungry, the oppressed and the voiceless (Ben Maclennan, Sapa, 2004-12-02).

In February 2006, Desmond Tutu took part in the 9th Assembly of the World Council of Churches, held in Porto Alegre, Brazil. There he manifested his commitment to ecumenism and praised the efforts of Christian churches to promote dialogue in order to diminish their differences. For Desmond, "a united church is no optional extra."

Beit Hanoun

Desmond Tutu was named to head a United Nations fact-finding mission to the Gaza Strip town of Beit Hanoun, where, in a November 2006 incident the Israel Defense Forces killed 19 civilians after troops wound up a week-long incursion aimed at curbing Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel from the town. Tutu planned to travel to the Palestinian territory to "assess the situation of victims, address the needs of survivors and make recommendations on ways and means to protect Palestinian civilians against further Israeli assaults," according to the president of the UN Human Rights Council, Luis Alfonso De Alba.[8]

Israeli officials expressed concern that the report would be biased against Israel. Tutu canceled the trip in mid-December, saying that Israel had refused to grant him the necessary travel clearance after more than a week of discussions. A spokesman from the Israeli foreign ministry indicated that no final decision had been made, to which Tutu responded, "At times not making a decision is making a decision. We couldn't obviously wait in limbo indefinitely."[9]

Quotes by Tutu

- "When missionaries came to South Africa, we had the land, they had the Bible. Then they told us, 'Let's close our eyes and pray.' When we opened our eyes we saw that we have the Bible, they have the land."

- "If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality."

Ubuntu theology

Despite sometimes being regarded as more of a political activist than a Christian leader, theology informed everything that Tutu did. He developed a type of theology based on the African concept of "ubuntu," which refers to human interdependence. God created us, said Tutu, as a single human family. For him, "social harmony … is the summum bonum—the greatest good." All are related to the whole of "creation" and "stewards" of "all of its glory and physicality."[2]. Ubuntu does not say, "I think therefore I am" but "I am human because I belong, I participate, I share." It subverts the idea that success by any means is permitted, such as "succeeding at the expense of others." Ultimate freedom is to be found in a human unity that recognizes no barriers, so that "We can be human only together, black and white, rich and poor, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and Jew."[2] Tutu had a warm relationship with leaders from faith communities other than his own.

Legacy

In an article published in the Ecumenical Review, B.J. de Klerk described Tutu as, alongside Nelson Mandela, an "icon of reconciliation" and an inspiration to many millions of people around the globe. Tutu, he wrote, "is a man who rejoices in the human spirit. His optimism as a devoted Christian, belief in the triumph of good over evil and the remarkable strength of the human spirit help him to overcome the different struggles in his life."[10]

Despite all his honors, Tutu remained at heart a humble priest and servant. He told of the time, when a passenger on his flight mistook him for Bishop Abel Muzorewa, asking an air hostess to request his autograph: "I tried to look modest, although I was thinking in my heart that there were some people who recognized a good thing when they saw it. As she handed me the book and I took out my pen, she said, 'you are Bishop Muzorewa, aren't you?'." "That certainly," writes Tutu, "helped keep my ego in check."[2]

by the time of apartheid's fall, Tutu had attained "worldwide respect" for his "uncompromising stand for justice and reconciliation and his unmatched integrity."[11] According to Allen, Tutu "made a powerful and unique contribution to publicizing the antiapartheid struggle abroad," particularly in the United States.[12] In the latter country, he was able to rise to prominence as a South African anti-apartheid activist because—unlike Mandela and other members of the ANC—he had no links to the South African Communist Party and thus was more acceptable to Americans amid the Cold War anti-communist sentiment of the period.[12]

On the day that the prisoner who became President was released, Mandela said of Tutu, "Here is a man who had inspired an entire nation with his words and his courage, who had revived the people's hope during the darkest of times."[13]

In the U.S., he was often compared to Martin Luther King Jr., with the African-American civil rights activist Jesse Jackson referring to him as "the Martin Luther King of South Africa."[14]

After the end of apartheid, Tutu became "perhaps the world's most prominent religious leader advocating gay and lesbian rights."[12] Ultimately, perhaps Tutu's "greatest legacy" was the fact that he gave "to the world as it entered the twenty-first century an African model for expressing the nature of human community."[12]

In a message of condolence upon the news of Tutu's death, Queen Elizabeth II described Tutu as "a man who tirelessly championed human rights in South Africa and across the world", and that his loss will be felt by the people across the Commonwealth, where "he was held in such high affection and esteem".[15]

Former United States president Barack Obama released a statement in part calling him a "universal spirit" and that he was "grounded in the struggle for liberation and justice in his own country, but also concerned with injustice everywhere".[16] President Joe Biden said that Tutu's legacy will "echo throughout the ages."[17] Former presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton also released statements upon his death.[18]

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, said in his tribute: "When you were in parts of the world where there was little Anglican presence and people weren't sure what the Anglican church was, it was enough to say "It's the Church that Desmond Tutu belongs to" – a testimony to the international reputation he had and the respect with which he was held."[19]

Pope Francis lamented his death and praised Tutu for promoting "racial equality and reconciliation in his native South Africa."[20]

Honors

Tutu gained many international awards and honorary degrees, particularly in South Africa, the United Kingdom, and United States. By 2003, he had approximately 100 honorary degrees.[11] Many schools and scholarships were named after him. For instance, in 2000 the Munsieville Library in Klerksdorp was renamed the Desmond Tutu Library, and at Fort Hare University, the Desmond Tutu School of Theology was launched in 2002.[11]

On October 16, 1984, Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Nobel Committee cited his "role as a unifying leader figure in the campaign to resolve the problem of apartheid in South Africa."[21] This was seen as a gesture of support for him and The South African Council of Churches which he led at that time. In 1987 Tutu was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award.[11]

In 2003, Tutu received the Golden Plate Award of the Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member Coretta Scott King.[22]

In 2015, Queen Elizabeth II graciously approved Desmond Tutu the honorary British award of The Order of the Companions of Honour. (CH).[23] Queen Elizabeth II appointed Tutu as a Bailiff Grand Cross of the Venerable Order of St. John in September 2017.[24]

In 2013 Tutu received the £1.1m ($1.6m) Templeton Prize for "his life-long work in advancing spiritual principles such as love and forgiveness."[25]

In 2018 the fossil of a Devonian tetrapod was found in Grahamstown by Rob Gess of the Albany Museum; this tetrapod was named Tutusius umlambo in Tutu's honor.[26]

Publications

Tutu authored several collections of sermons and other writings:

- Desmond Tutu - Crying in the Wilderness Paperback. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1982. ISBN 978-0264671192

- Hope and Suffering: Sermons and Speeches. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1984. ISBN 9780802836144

- The Words of Desmond Tutu. NY: Newmarket Press, 1989. ISBN 9781557040381, with Naomi Tutu

- Worshipping Church in Africa. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780822364016

- The Rainbow People of God: The Making of a Peaceful Revolution. Image, 1996. ISBN 0385483740

- The Essential Desmond Tutu. Bellville: Mayibuye Books; Cape Town: D. Philip Publishers 1997. ISBN 9780864863461

- No Future without Forgiveness. NY: Doubleday, 1999. ISBN 9780385496896

- The African Prayerbook. NY: Hodder & Stoughton Religious Division, 2000. ISBN 978-0340642429

- God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time. NY: Doubleday, 2004. ISBN 978-0385477840

Tutu also contributed to numerous books:

- Bounty in Bondage: Anglican Church in Southern Africa - Essays in Honour of Edward King, Dean of Cape Town, with Frank England, Torguil Paterson, and Torquil Paterson. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1989. ISBN 9780869753835

- Resistance Art in South Africa, with Sue Williamson, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1990. ISBN 9780312041427

- Freedom from Fear: And Other Writings, with Vaclav Havel and Aung San Suu Kyi, BY: Penguion, 1995. ISBN 9780140170894

- Exploring Forgiveness, with Robert D. Enright and Joanna North. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998. ISBN 9780299157708

- Love in Chaos: Spiritual Growth and the Search for Peace in Northern Ireland, with Mary McAleese NY: Continuum, 1999. ISBN 9780826411372

- At the Side of Torture Suvivors: Treating a Terrible Assault on Human Dignity, with Bahman Nirumand, Sepp Graessner and Norbert Gurris. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Pres, 2001. ISBN 9780801866272

- Place of Compassion, with Kenneth E. Luckman. Hertford, England: Authors OnLine, 2001. ISBN 9780755200283

- Passion for Peace: Exercising Power Creatively with Stuart Rees, Sydney: UNSW Press, 2002. ISBN 9780868407500

- Out of Bounds, (New Windmills) with Beverley Naidoo. NY: HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 9780060507992

- Fly, Eagle, Fly! with Christopher Gregorowski and Niki Daly. NY: Margaret K. McElderry Books, 2003. ISBN 9780689823985

- Sex, Love and Homophobia: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Lives, with Amnesty International, Vanessa Baird and Grayson Perry. London: Amnesty International, 2004. ISBN 9781873328576

- Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation, with Gustavo Gutierrez and Marc H. Ellis. 2004. ISBN 9780883443583

- Radical Compassion: The Life and Times of Archbishop Ted Scott with Hugh McCullum, Geneva: World Council of Churches, 2004. ISBN 2825414034

- Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another and Other Lessons from the Desert Fathers. with Rowan Williams. Boston: New Seeds, 2005. ISBN 978-1590302316

- Mandela, with Charlene Smith. Cape Town: Struik Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-1868722068

Notes

- ↑ Tutu and Tintin to be honored by Dalai Lama International Campaign for Tibet, May 17, 200. Retrieved March 22,December 27, 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Desmond Tutu, God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time (New York: Doubleday, 2004, ISBN 978-0385477840).

- ↑ Stanley Uys and Dan van der Vat, The Most Rev Desmond Tutu obituary The Guardian, December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ↑ South Africa Begins a Week of Mourning for Desmond Tutu The New York Times, December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Dinky Mkhize, Tutu Dismisses Uproar Over Gay American Bishop The Washington Post, August 16, 2003. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Desmond Tutu, Apartheid in the Holy Land The Guardian, April 28, 2002. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Desmond Tutu: Israel guilty of apartheid in treatment of Palestinians The Jerusalem Post, March 10, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Jacob Slosberg, Tutu to head UN rights mission to Gaza The Jerusalem Post, November 29, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Israel ‘turns down’ Tutu mission Al Jazeera, December 11, 2006. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ B.J. De Klerk, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu: Living Icons of Reconciliation Ecumenical Review 55(4) (October 2003): 322-334. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Steven D. Gish, Desmond Tutu: A Biography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0313328602).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 John Allen, Rabble-Rouser for Peace: The Authorized Biography of Desmond Tutu (Free Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0743269377).

- ↑ Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (Boston: Little Brown & Co, 1995), 678.

- ↑ Shirley Du Boulay, Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1988, ISBN 978-0802836496).

- ↑ Desmond Tutu: Queen leads UK tributes to archbishop BBC News, December 26, 2021.

- ↑ UN chief calls Desmond Tutu 'an inspiration to generations' Associated Press, December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Olafimihan Oshin, Bidens: Desmond Tutu's legacy will 'echo throughout the ages' The Hill, December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Kevin Shalvey,Ivan Pereira, and Christine Theodorou, Tutu remembered as 'true humanitarian' dedicated to human rights ABC News, December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Archbishop of Canterbury pays tribute to Archbishop Desmond Tutu The Archbishop of Canterbury, December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Pope laments death of 'servant of the Gospel' Archbishop Tutu Vatican News, December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ The Nobel Peace Prize 1984 The Nobel Prize. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Summit Overview Academy of Achievement. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Honorary awards, 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Order of St John The Gazette, September 21, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Templeton Prize Laureates Templeton Prize. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ↑ Steven Lang, Grahamstown scientist's new fossil scoop Grocott's Mail, June 7, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, John. Rabble-Rouser for Peace: The Authorized Biography of Desmond Tutu. Free Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0743269377

- Du Boulay, Shirley. Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1988. ISBN 978-0802836496

- Battle, Michael. Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology of Desmond Tutu. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0829811582

- Gish, Steven D. Desmond Tutu: A Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0313328602

- Hein, David. "Bishop Tutu's Christology." Cross Currents 34 (1984): 492-499.

- Hein, David. "Religion and Politics in South Africa." Modern Age 31 (1987): 21-30.

- Mandela, Nelson. Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Boston: Little Brown & Co, 1995. ISBN 0316548189

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

- Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation

- Tutu Foundation UK

- Desmond Tutu Nobel Lecture The Nobel Prize

- IMDB Profile

| Preceded by: Philip Welsford Richmond Russell |

Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town 1986-1996 |

Succeeded by: Njongonkulu Ndungane |

| |||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.