Difference between revisions of "Civilization" - New World Encyclopedia

(First 100 words) |

|||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

== Further reading== | == Further reading== | ||

| + | |||

*[http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/interactive/civilisations/ BBC on civilization] | *[http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/interactive/civilisations/ BBC on civilization] | ||

| + | |||

* [http://www.alamut.com/subj/economics/misc/clash.html "The Clash of Civilizations?"], text of the original essay by Samuel P. Huntington (1993) | * [http://www.alamut.com/subj/economics/misc/clash.html "The Clash of Civilizations?"], text of the original essay by Samuel P. Huntington (1993) | ||

| + | |||

*Felipe Fernandez-Armesto (2001) ''Civilizations'', London: Free Press. ISBN 0743202481 | *Felipe Fernandez-Armesto (2001) ''Civilizations'', London: Free Press. ISBN 0743202481 | ||

| + | |||

* http://history-world.org/ | * http://history-world.org/ | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Wilkinson, D. (1987). Central Civilization. ''Comparative Civilizations Review'', 4, 31-59. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Wilkinson, D. (1999). Unipolarity without Hegemony. ''International Studies Review'', 1(2), 141-172. | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

Revision as of 16:53, 16 January 2006

Civilization refers to a complex human society, in which people live in groups of settled dwellings comprising cities. Early civilizations developed in many parts of the world, primarily where there was adequate water available. The causes of the growth and decline of civilizations, and their expansion to a potential world society, are complex. However, civilizations require not only external advaneces to prosper, they also require the society to maintain and develop good social and ethical relationships.

Definition

The term "civilization" or "civilisation" comes from the Latin word civis, meaning "citizen" or "townsman." By the most minimal, literal definition, a "civilization" is a complex society.

Anthropologists distinguish civilizations in which many of the people live in cities (and obtain their food from agriculture), from tribal societies, in which people live in small settlements or nomadic groups (and subsist by foraging, hunting, or working small horticultural gardens). When used in this sense, civilization is an exclusive term, applied to some human groups and not others.

"Civilization" can also mean a standard of behavior, similar to etiquette. Here, "civilized" behavior is contrasted with crude or "barbaric" behavior. In this sense, civilization implies sophistication and refinement.

Another use of the term "civilization" combines the meanings of complexity and sophistication, implying that a complex, sophisticated society is naturally superior to less complex, less sophisticated societies. This point of view has been used to justify racism and imperialism – powerful societies have often believed it was their right to "civilize," or culturally dominate, weaker ones ("barbarians"). This act of civilizing weaker peoples has been called the "White Man's Burden".

In a broader sense, "civilization" often refers to any distinct society, whether complex and city-dwelling, or simple and tribal. This usage is less exclusive and ethnocentric than the previous definitions, and is almost synonymous with culture. Thus, the term "civilization" can also describe the culture of a complex society, not just the society itself. Every society, civilization or not, has a specific set of ideas and customs, and a certain set of items and arts, that make it unique. Civilizations have more intricate cultures, including literature, professional art, architecture, organized religion, and complex customs associated with the elite.

Samuel P. Huntington, in his essay The Clash of Civilizations, defined civilization as "the highest cultural grouping of people and the broadest level of cultural identity people have short of that which distinguishes humans from other species." In this sense, a Christian woman of African-American descent, living in the United States of America, has many roles that she identifies with, but she is, above all, a member of "Western civilization".

Finally, "civilization" can refer to human society as a whole, as in the sentence "A nuclear war would wipe out civilization," or "I'm glad to be safely back in civilization after being lost in the wilderness for 3 weeks." It is also used in this sense to refer to a potential global civilization.

Problems with the term "civilization"

As discussed above, "civilization" has a variety of meanings, and its use can lead to confusion and misunderstanding. Moreover, the term carried a number of value-laden connotations. It might bring to mind qualities such as superiority, humaneness, and refinement. Indeed, many members of civilized societies have seen themselves as superior to the "barbarians" outside their civilization.

Many postmodernists, and a considerable proportion of the wider public, argue that the division of societies into "civilized" and "uncivilized" is arbitrary and meaningless. On a fundamental level, they say there is no difference between civilizations and tribal societies; that each simply does what it can with the resources it has. In this view, the concept of "civilization" has merely been the justification for colonialism, imperialism, genocide, and coercive acculturation.

For these reasons, many scholars today avoid using the term "civilization" as a stand-alone term, preferring to use urban society or intensive agricultural society, which are less ambiguous, and more neutral terms. "Civilization," however, remains in common academic use when describing specific societies, such as the "Mayan Civilization."

What characterizes civilization

Historically, societies referred to as civilizations have shared some or all of the following traits:

- Intensive agricultural techniques, such as the use of human power, crop rotation, and irrigation. This has enabled farmers to produce a surplus of food beyond what is necessary for their own subsistence.

- A significant portion of the population that does not devote most of its time to producing food. This permits a division of labor. Those who do not occupy their time in producing food may obtain their food through trade as in modern capitalism or may have the food provided to them by the state as in Ancient_Egypt. This is possible because of the food surplus described above.

- The gathering of these non-food producers into permanent settlements, called cities.

- A social hierarchy. This can be a chiefdom, in which the chieftain of one noble family or clan rules the people; or a state society, in which the ruling class is supported by a government or bureaucracy. Political power is concentrated in the cities.

- The institutionalized control of food by the ruling class, government or bureaucracy.

- The establishment of complex, formal social institutions such as organized religion and education, as opposed to the less formal traditions of other societies.

- Development of complex forms of economic exchange. This includes the expansion of trade and may lead to the creation of money and markets.

- The accumulation of more material possessions than in simpler societies.

- Development of new technologies by people who are not busy producing food. In many early civilizations metallurgy was an important advancement.

- Advanced development of the arts, including writing.

Based on these criteria, some societies, like that of Ancient Greece, are clearly civilizations, whereas others, like the Bushmen, are not. However, the distinction is not always so clear. In the Pacific Northwest of the United States, for example, an abundant supply of fish guaranteed that the people had a surplus of food without any agriculture. The people established permanent settlements, a social hierarchy, material wealth, and advanced art (most famously totem poles), all without the development of intensive agriculture. Meanwhile, the Pueblo culture of southwestern North America developed advanced agriculture, irrigation, and permanent, communal settlements such as Taos Pueblo. However, the Pueblo never developed any of the complex institutions associated with civilizations. Today, many tribal societies live inside states and under their laws. The political structures of civilization were superimposed on their way of life, and so they occupy a middle ground between tribal and civilized.

Early civilizations

Early human settlements were built mostly in river valleys where the land was fertile and suitable for agriculture. Easy access to a river or a sea was important not only for food (fishing) or irrigation, but also for transportation and trade. The earliest known civilizations arose in the Nile valley of Ancient Egypt, on the island of Crete in the Aegean Sea, around the Euphrates and Tigris rivers of Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley region of modern Pakistan, and in the Huang He valley (Yellow River) of China. The inhabitants of these areas built cities, created writing systems, learned to make pottery and use metals, domesticated animals, and created complex social structures with class systems.

Ancient Egypt

Both anthropological and archaeological evidence indicate the existence of a grain-grinding and farming culture along the Nile in the 10th millennium B.C.E. Evidence also indicates human habitation in the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the Sudan border, before 8000 B.C.E. Climate changes and/or overgrazing around 8000 B.C.E. began to desiccate the pastoral lands of Ancient Egypt, eventually forming the Sahara (c.2500 B.C.E.), and early tribes naturally migrated to the Nile river where they developed a settled agricultural economy, and more centralized society. Domesticated animals had already been imported from Asia between 7500 B.C.E. and 4000 B.C.E. There is evidence of pastoralism and cultivation of cereals in the East Sahara in the 7th millennium B.C.E. The earliest known artwork of ships in Ancient Egypt dates to 6000 B.C.E.

By 6000 B.C.E. Pre-dynastic Egypt (in the southwestern corner of Egypt) was herding cattle and constructing large buildings. Symbols on Gerzean pottery (c. 4000 B.C.E.) resemble traditional Egyptian hieroglyph writing. In Ancient Egypt mortar (masonry) was in use by 4000 B.C.E., and ancient Egyptians were producing ceramic faience as early as 3500 B.C.E. There is evidence that ancient Egyptian explorers may have originally cleared and protected some branches of the 'Silk Road'. Medical institutions are known to have been established in Egypt since as early as circa 3000 B.C.E. Ancient Egypt also gains credit for the tallest ancient pyramids, and barge transportation.

Aegean civilizations

Aegean civilization is the general term for the prehistoric civilizations in Greece and the Aegean. The earliest inhabitants of Knossos, the center of Minoan Civilization on Crete, date back to the 7th millenium B.C.E. The Aegean civilization developed three distinctive features:

- An indigenous writing system existed which consisted of characters with which only a very small percentage were identical, or even obviously connected, with those of any other script.

- Aegean Art is distinguishable from those of other early periods and areas. While borrowing from other contemporary arts Aegean craftsman gave their works a new character, namely realism. The fresco-paintings, ceramic motifs, reliefs, free sculpture and toreutic handiwork of Crete provde the clearest examples.

- Aegean Architecture: Aegean palaces are of two main types.

- First (and perhaps earliest in time), the chambers are grouped around a central court, being linked one with the other in a labyrinthine complexity, and the greater oblongs are entered from a long side and divided longitudinally by pillars.

- Second, the main chamber is of what is known as the megaron type, i.e. it stands free, isolated from the rest of the plan by corridors, is entered from a vestibule on a short side, and has a central hearth, surrounded by pillars and perhaps open to the sky; there is no central court, and other apartments form distinct blocks. In spite of many comparisons made with Egyptian, Babylonian and Hittite plans, both these arrangements remain out of keeping with any remains of earlier or contemporary structures elsewhere.

Fertile Crescent

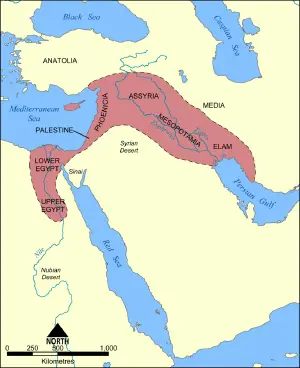

The Fertile Crescent is a historical region in the Middle East incorporating Ancient Egypt, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. Watered by the Nile, Jordan, Euphrates and Tigris rivers and covering some 400-500,000 square kilometers, the region extends from the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea around the north of the Syrian Desert and through the Jazirah and Mesopotamia to the Persian Gulf.

The Fertile Crescent has an impressive record of past human activity. As well as possessing many sites with the skeletal and cultural remains of both pre-modern and early modern humans (e.g. at Kebara Cave in Israel), later Pleistocene hunter-gatherers and Epipalaeolithic semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers (the Natufians), this area is most famous for its sites related to the origins of agriculture. The western zone around the Jordan and upper Euphrates rivers gave rise to the first known Neolithic farming settlements, which date to around 9,000 B.C.E. (and includes sites such as Jericho). This region, alongside Mesopotamia (which lies to the east of the Fertile Crescent, between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates), also saw the emergence of early complex societies during the succeeding Bronze Age. There is also early evidence from this region for writing, and the formation of state-level societies. This has earned the region the nickname "The Cradle of Civilization."

As crucial as rivers were to the rise of civilization in the Fertile Crescent, they were not the only factor in the area's precocity. The Fertile Crescent had a climate which encouraged the evolution of many annual plants, which produce more edible seeds than perennials, and the region's dramatic variety of elevation gave rise to many species of edible plants for early experiments in cultivation. Most importantly, the Fertile Crescent possessed the wild progenitors of the eight Neolithic founder crops important in early agriculture (i.e. wild progenitors to emmer, einkorn, barley, flax, chick pea, pea, lentil, bitter vetch), and four of the five most important species of domesticated animals - cows, goats, sheep, and pigs - and the fifth species, the horse, lived nearby.

Indus valley civilization

The earliest known farming cultures in south Asia emerged in the hills of Balochistan, Pakistan, in the 7th millennium B.C.E. These semi-nomadic peoples domesticated wheat, barley, sheep, goat, and cattle. Pottery was in use by the 6th millennium B.C.E. Their settlements consisted of mud buildings that housed four internal subdivisions. Burials included elaborate goods such as baskets, tools made of stone bone, beads, bangles, pendants, and occasionally animal sacrifices. Figurines and ornaments of sea shells, limestones, turquoise, lapis lazul, sandstones and polished copper have also been found in the area.

By the 4th millennium B.C.E. there is evidence of manufacturing, including stone and copper drills, updraft kilns, large pit kilns, copper melting crucibles, and button seal devices with geometric designs. Villagers domesticated numerous crops, including peas, sesame seed, and cotton, plus a wide range of domestic animals, including the water buffalo, which still remains essential to intensive agricultural production throughout Asia today. There is also evidence of shipbuilding craft. Archaeologists have discovered a massive, dredged canal and docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal, India, perhaps the world's oldest sea-faring harbor. Judging from the dispersal of artifacts, their trade networks integrated portions of Afghanistan, the Persian (Iran) coast, northern and central India, Mesopotamia, and Ancient Egypt.

Archaeologists studying the remains of two men from Mehrgarh, Pakistan, discovered that peoples in the Indus Valley had knowledge of medicine and dentistry as early as circa 3300 B.C.E. The Indus Valley Civilization is credited with the earliest known use of decimal fractions in a uniform system of ancient weights and measures, as well as negative numbers. Ancient Indus Valley artifacts include beautiful, glazed stone faïence beads. The Indus Valley Civilization boasts the earliest known accounts of urban planning. As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and recently discovered Rakhigarhi, their urban planning included the world's first urban sanitation systems. Evidence suggests efficient municipal governments. Streets were laid out in perfect grid patterns comparable to modern New York. Houses were protected from noise, odors and thieves. The sewage and drainage systems developed and used in cities throughout the Indus Valley were far more advanced than that of contemporary urban sites in the Middle East.

China

China is one of the world's oldest continuous major civilizations, with written records dating back 3,500 years. China was inhabited, possibly more than a million years ago, by Homo erectus. Perhaps the most famous specimen of Homo erectus found in China is the so-called Peking Man (北京人) found in 1923. The Homo sapiens or modern human might have reached China about 65,000 years ago from Africa. Early evidence for proto-Chinese rice paddy agriculture is carbon-dated to about 6000 B.C.E., and associated with the Peiligang culture (裴李崗文化) of Xinzheng county (新鄭縣), Henan (河南省). With agriculture came increased population, the ability to store and redistribute crops, and to support specialist craftsmen and administrators. In late Neolithic times, the Huang He (黃河) valley began to establish itself as a cultural center, where the first villages were founded; the most archaeologically significant of those was found at Banpo (半坡), Xi'an (西安).

Turtle shells with markings reminiscent of ancient Chinese writing from the Shang Dynasty (商朝) have been carbon dated to around 1,500 B.C.E. These records suggest that the origins of Chinese civilization started with city-states that may go back more than 5,000 years.

Expansion of civilization

The nature of civilization is that it seeks to spread, to expand, and it has the means by which to do this. Civilization has been spread by introducing agriculture, writing system, and religion to uncivilized tribes. The uncivilized people then adapt to civilized behavior. Civilization has also been spread by force, often with religion used to justify its actions.

Nevertheless some tribes or peoples still remained uncivilized. Known as primitive_cultures, they do not have hierarchical governments, organized religion, writing systems or controlled economic exchange. The little hierarchy that exists, for example respect for the elderly, is by mutual agreement not enforced by any ruling authority.

Growth and decline of civilizations

Historically, civilizations experience cycles of birth, life, decline and death, often supplanted by a new civilization with a potent new culture. While this observation is generally not disputed, a variety of reasons for the growth and decline of civilizations have been proposed.

Many 19th-century anthropologists backed a theory called cultural evolution. They believed that people naturally progress from a simple to a superior, civilized state. John Wesley Powell, for example, classified all societies as "Savage," "Barbarian," and "Civilized" – the first two of which would shock most anthropologists today.

Today, most social scientists believe at least to some extent in cultural relativism, the view that complex societies are not by nature superior, more humane, or more sophisticated than less complex or technologically advanced groups. This view has its roots in the early twentieth-century writings of Franz Boas. Boas claimed that development of any particular civilization cannot be understood without understanding the whole history of that civilization. Thus each civilization has its own unique birth, peak, and decline, and cannot be compared to any other civilization.

English biologist John Baker, in his 1974 book Race, challenged this view. His highly controversial work explored the nature of civilizations, presenting 23 criteria that characterize civilizations as superior to non-civilizations. He tried to show a relationship between cultures and the biological disposition of their creators, claiming that some races were just biologically and evolutionary predisposed for greater cultural development. In this way, some races were more creative than others, while others were more adaptive to new ideas.

Mid twentieth-century historian Arnold J. Toynbee explored civilizational processes in his multi-volume A Study of History, which traced the rise and, in most cases, the decline of 21 civilizations and five "arrested civilizations." Toynbee viewed the whole of history as the rise and fall of civilizations. "Western Civilization", for example, together with “Orthodox civilization” (Rusia and the Balkans) developed after the fall of the Roman Empire, thus succeeding Greco-Roman civilization. According to Toynbee, civilizations develop in response to some set of challenges in the environment, which require creative solutions that ultimatelly reorient the entire society. Examples of this when Sumerians developed irrigation techniques to grow crops in Iraq, or when the Catholic Church included pagan tribes into their religious community. When civilizations utilize new creative ideas, then they overcome challenges and grow. When they are rigid, failing to respond to challenges, they decline. According to Toynbee, most civilizations declined and fell because of moral or religious decline, which led to rigidity and the inability to be creative.

Thus, there are many factors to be considered in understanding the course of any civilization. These include both social, or internal, factors, such as the disposition of the people and the structure of the society, and environmental, or external, factors, such as the availability of water for agriculture and transportation. Whether a civilization declines or continues to develop also depends on both internal and external factors, as they determine the response to the various challenges, also both internal and external, that the civilization encounters.

Negative views of civilization

Members of civilizations have sometimes shunned them, believing that civilization restricts people from living in their natural state. Religious ascetics have often attempted to curb the influence of civilization over their lives in order to concentrate on spiritual matters. Monasticism represents an effort by these ascetics to create a life somewhat apart from their mainstream civilizations.

Environmentalists also criticize civilizations for their exploitation of the environment. Through intensive agriculture and urban growth, civilizations tend to destroy natural settings and habitats. Proponents of this view believe that traditional societies live in greater harmony with nature than "civilized" societies. The "sustainable living" movement is a push from some members of civilization to regain that harmony with nature.

Marxists have claimed "that the beginning of civilization was the beginning of oppression." They argue that as food production and material possessions increased, wealth became concentrated in the hands of the powerful, and the communal way of life among tribal people gave way to aristocracy and hierarchy.

"Primitivism" is a modern philosophy opposed to civilization for all of the above reasons, accusing civilizations of restricting humans, oppressing the weak, and damaging the environment.

The future of civilizations

The Kardashev scale, proposed by Russian astronomer Nikolai Kardashev, classifies civilizations based on their level of technological advancement, specifically measured by the amount of energy a civilization is able to harness. The Kardashev scale makes provisions for civilizations far more technologically advanced than any currently known to exist.

Currently, world civilization is in a stage that may be characterized as an "industrial society," superseding the previous "agrarian society." Some believe that the world is undergoing another transformation, in which civilizations are entering the stage of the "informational society."

Political scientist Samuel P. Huntington has argued that the defining characteristic of the 21st century will be a "clash of civilizations." According to Huntington, conflicts between civilizations will supplant the conflicts between nation-states and ideologies that characterized the 19th and 20th centuries.

Many theorists argue that the entire world has already become integrated into a single "world system," a process known as globalization. Different civilizations and societies all over the globe are economically, politically, and even culturally interdependent in many ways. According to David Wilkinson, civilizations can be culturally heterogeneous, like "Western Civilization," or relatively homogeneous, like the Japanese civilization. What Huntington calls the "clash of civilizations" might be characterized by Wilkinson as a clash of cultural spheres within a single global civilization.

In the future civilizations may be expected to increase in extent, leading to a single world civilization, as well as to advance technologically. However, technological and other external improvements may not be the most important aspect of future civilizations – growth on the internal leval (psychological, social, even spiritual) is also needed for any civilization to avoid stagnation and decline.

Ultimately, the future of civilizations may depend on the answer to whether history progresses as a series of random events, or whether it has design and purpose, known by religious people as divine providence.

Further reading

- "The Clash of Civilizations?", text of the original essay by Samuel P. Huntington (1993)

- Felipe Fernandez-Armesto (2001) Civilizations, London: Free Press. ISBN 0743202481

- Wilkinson, D. (1987). Central Civilization. Comparative Civilizations Review, 4, 31-59.

- Wilkinson, D. (1999). Unipolarity without Hegemony. International Studies Review, 1(2), 141-172.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.