Borobudur

| Borobudur | |

| |

| Building information | |

|---|---|

| Location | near Magelang, Central Java |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Architect | Gunadharma |

| Completion date | circa AD 800 |

| Style | stupa and candi |

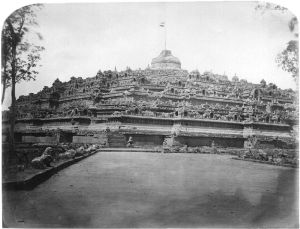

Borobudur, a ninth century Buddhist Mahayana monument in Central Java, Indonesia comprises six square platforms topped by three circular platforms, decorated with 2,672 relief panels and 504 Buddha statues.[1] Seventy-two Buddha statues seated inside perforated stupa surround a main dome, located at the center of the top platform.

The monument serves both as a shrine to the Lord Buddha and a place for Buddhist pilgrimage. The journey for pilgrims begins at the base of the monument and follows a path circumambulating the monument while ascending to the top through the three levels of Buddhist cosmology, namely, Kamadhatu (the world of desire); Rupadhatu (the world of forms); and Arupadhatu (the world of formless). During the journey, the monument guides the pilgrims through a system of stairways and corridors with 1,460 narrative relief panels on the wall and the balustrades.

Evidence suggests Indians abandoned Borobudur following the fourteenth century decline of Buddhist and Hindu kingdoms in Java, and the Javanese conversion to Islam.[2] Sir Thomas Raffles, the British ruler of Java rediscovered it in 1814. Since then, Borobudur has been preserved through several restorations. The Indonesian government and UNESCO, undertook the largest restoration project between 1975 and 1982. UNESCO designated Borobudur a World Heritage Site after completion of the restoration.[3] Borobudur still serves as a pilgrimage site, once a year Buddhists in Indonesia celebrate Vesak at the monument. Borobudur constitutes Indonesia's single most visited tourist attraction.[4][5][6]

Etymology

In Indonesian, candi, or formerly chandi means temple. The term also more loosely describes any ancient structure, for example, gates and bathing structures. The origins of the name Borobudur remains unclear,[7] as the original name of most candi has been lost.[7] The Sir Thomas Raffles book on Java historyT first mentions the name 'Borobudur'.[8] Raffles wrote about the existence of a monument called borobudur, but no other older documents suggest the same name.[7] Nagarakertagama, written by Mpu Prapanca in AD 1365, represents the only written old Javanese manuscript hinting at the monument. It mentions Budur as a Buddhist sanctuary, which likely associates with Borobudur, but the manuscript lacks any further information to make a definite identification.

The name 'Bore-Budur', and thus 'BoroBudur', may have been written by Raffles in English grammar to mean the nearby village of Bore; most candi have names derived from a nearby village. If it followed Javanese language, the monument should have been named as BudurBoro. Raffles also suggested that Budur might correspond to the modern Javanese word Buda ('ancient') - i.e., 'ancient Boro'.[7] Another hypothesis states that 'Boro' may have taken from an old Javanese term bhara ('honourable'), describing the monument as "The Honourable Buddha." Another interpretation comes from the Javanese word biara ('monastery'), which refers the monument as the 'monastery of Budur'.

Location

A number of Buddhist and Hindu temple compounds are located approximately 40 km (25 miles) northwest of Yogyakarta, on an elevated area between two twin volcanoes, Sundoro-Sumbing and Merbabu-Merapi, and the Progo river. According to local myth, the area known as Kedu Plain is a Javanese 'sacred' place and has been dubbed 'the garden of Java' due to its high agricultural fertility.[9] During the first restoration, it was discovered that three Buddhist temples in the region, Borobudur, Pawon and Mendut, are in one straight line position.[10] It might be accidental, but the temples' alignment is in conjunction with a native folk tale that a long time ago, there was a brick-paved road from Borobodur to Mendut with walls on both sides.

Unlike other temples, which are built on a flat surface, Borobudur was built on a bedrock hill, 265 m (869 ft) above sea level and 15 m (49 ft) above the floor of the dried-out paleolake.[11] The lake's existence was the subject of intense discussion among archaeologists in the twentieth century; Borobudur was thought to have been built on a lake shore or even floated on a lake. In 1931, a Dutch artist and a scholar of Hindu and Buddhist architecture, W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp, developed a theory that Kedu Plain was once a lake and Borobudur initially represented a lotus flower floating on the lake.[9] Lotus flowers are found in almost every Buddhist work of art, often serving as a throne for buddhas and base for stupas. The architecture of Borobudur itself suggests a lotus depiction, in which Buddha postures in Borobudur symbolize the Lotus Sutra, mostly found in many Mahayana Buddhism (a school of Buddhism widely spread in southeast and east Asia regions) texts. Three circular platforms on the top are also thought to represent a lotus leaf.[11] Nieuwenkamp's theory, however, was contested by many archaeologists because the natural environment surrounding the monument is a dry land.

Geologists, on the other hand, support Nieuwenkamp's view, pointing out clay sediments found near the site.[12] A study of stratigraphy, sediment and pollen samples conducted in 2000 supports the existence of a paleolake environment near Borobudur,[11] which corroborates the doubts had raised by archaeologists. The lake area, however, fluctuated with time; a study also proves that Borobudur was near the lake shore circa thirteenth and fourteenth century. River flows and volcanic activities shape the surrounding landscape, including the lake. One of the most active volcanoes in Indonesia, Mount Merapi, is in the direct vicinity of Borobudur and has been very active since the Pleistocene.[13]

History

Construction

There is no written record of who built Borobudur, or of its intended purpose.[14] The construction time is estimated by comparison between carved reliefs on the temple's hidden foot and the inscriptions commonly used in royal charters during the eight and ninth centuries. It is likely Borobudur was founded around AD 800.[14] This corresponds to the period between AD 760–830, the peak of the Sailendra dynasty in Central Java.[15], when it was under the influence of the Srivijayan Empire. The construction is estimated to have taken 75 years and was completed in 825, during the reign of Srivijayan Maharaja Samaratunga.[16][17]

There is confusion between Hindu and Buddhist rulers in Java around that time. The Sailendras are known as ardent followers of Lord Buddha, although stone inscriptions found at Sojomerto suggest they were Hindus.[16] It was during this time that many Hindu and Buddhist monuments were built on the plains and mountain around the Kedu Plain. The Buddhist monuments, including Borobudur, were erected around the same time as the Hindu Shiva Prambanan temple compound. In AD 732, king Sanjaya, the founder of the Sailendra dynasty, commissioned a Hindu Shiva lingga sanctuary to be built on the Ukir hill, only 10 km (6.2 miles) east of Borobudur. Sanjaya's immediate successor, Rakai Panangkaran, was associated with a Buddhist Kalasan temple, as shown in the Kalasan Charter dated AD 778. Anthropologists believe that religion in Java has never been a serious conflict.[18] It was possible for a Hindu king to patronize the establishment of a Buddhist monument; or for a Buddhist king to act likewise.[18] The official religion could take place without affecting the continuity of a dynasty and of cultural life.

Abandonment

For centuries, Borobudur lay hidden under layers of volcanic ash and jungle growth. The facts behind the desertion of the monument remain a mystery. It is unknown until when the monument was still in active use and when it ceased to function as the pilgrimage center of Buddhism.

A general assumption is that the temples were disbanded when the population were converted to Islam in the fifteenth century.[19] Another theory is that a famine caused by a volcanic eruption (est. circa AD 1006) had forced local inhabitants to leave their lands and the monument.[11] The event was said to trigger the movement of Javanese power from the Kedu Plain area to the east of Java nearby the Brantas valley as early as AD 928.

However, the great monument was never completely removed from the local people's memory. Instead of glorifying story about the monument, the memory was then gradually shifted into a more superstitious beliefs associated with bad luck and misery. Two old Javanese manuscripts of the eighteenth century mention a case of bad luck associated with the monument. According to the Babad Tanah Jawi (or the History of Java), the monument was a fatal factor for a rebel who revolted against the king of Mataram in AD 1709.[2] The hill was besieged and the insurgents were defeated and sentenced to death by the king. In the Babad Mataram (or the History of the Mataram Kingdom), the monument was associated with the misfortune of the crown prince of the Yogyakarta Sultanate in AD 1757.[20] In spite of a restriction to visit the monument, he took what is written as the knight who was captured in a cage (a statue in one of the perforated stupas). As soon as he arrived at his palace, he died unexpectedly after a one-day illness.

Rediscovery

Following the Anglo-Dutch Java War, Java was under British administration from 1811 to 1816. The appointed governor was Lieutenant Governor-General Thomas Stamford Raffles, who had a great interest in the history of Java. He collected Javan antiques and made notes through contacts with local inhabitants during his tour throughout the island. On an inspection tour to Semarang in 1814, he was informed about a big monument called Chandi Borobudur deep in a jungle near the village of Bumisegoro.[20] He was not able to make the discovery himself and he sent H.C. Cornellius, a Dutch engineer, to investigate.

In two months, Cornellius and his 200 men cut down trees, burned down vegetation and dug away the earth to reveal the monument. Due to the danger of collapse, he could not unearth all galleries. He reported his findings to Raffles including various drawings. Although the discovery is only mentioned by a few sentences, Raffles has been credited with the monument's recovery and bringing it to the world's attention.[8]

Hartmann, a Dutch administrator of the Kedu region, continued Cornellius' work and in 1835 the whole monument was finally unearthed. His interest in Borobudur was more personal rather than official. Hartmann did not, however, write any reports of his activities; in particular, the alleged story that he discovered the large statue of Buddha in the main stupa.[21] The main stupa is empty. In 1842, Hartmann investigated the main dome although what he discovered remains unknown. The Dutch East Indies government then commissioned a Dutch engineering official, F.C. Wilsen, who in 1853, reported a large Buddha statue the size of one hundred other Borobudur statues.

Besides making hundreds of relief sketches, Wilsen studied the monument itself, preparing three articles on it. The Dutch East Indies government, meanwhile, had appointed J.F.G. Brumund to make a detail study of the monument, which was completed in 1859. Brumund intended to publish an article supplemented by Wilsen's drawings. The colonial government, however, decided otherwise and Brumund subsequently refused to cooperate. The government then commissioned another scholar, C. Leemans, who compiled a monograph based on Brumund's and Wilsen's sources. In 1873, the first monograph of the detailed study of Borobudur was published, followed by its French translation a year later.[21] The first photograph of the monument was taken in 1873 by a Dutch-Flemish engraver, Isidore van Kinsbergen.[22]

Appreciation of the site developed slowly. Some reliefs and ornaments were routinely removed by thieves and souvenir hunters. In 1882, the chief inspector of cultural artefacts recommended that Borobudur be entirely disassembled with the reliefs placed in museums due to the unstable condition of the monument.[22] The government then appointed an archeologist, Groenveldt, to undertake a thorough investigation of the site and assess the actual condition of the monument. The report found that the fears over its condition were unjustified and recommended the monument be left intact.

Contemporary events

Following the major 1973 renovation funded by UNESCO,[23] Borobudur is once again used as a place of worship and pilgrimage. Once a year, during the full moon in May or June, Buddhists in Indonesia observe Vesak (Indonesian: Waisak) day commemorating the birth, death, and the time when Boddhisatva attained the highest wisdom to become Buddha. Vesak is an official national holiday in Indonesia[24] and the ceremony is centered at the three Buddhist temples by walking from Mendut to Pawon and ending at Borobudur.[25]

The monument is visited daily by tourists and is the single most visited tourist attractions in Indonesia. In 1974, 260,000 tourists of whom 36,000 were foreigners visited the monument.[5] The figure hiked into 2.5 million visitors annually (80% were domestic tourists) in the mid 1990s, before the country's economy crisis.[6] Tourism development, however, has been criticized for not including the local community on which occasional local conflict has arisen.[5] In 2003, residents and small businesses around Borobudur organized several meetings and poetry protests, objecting to a provincial government plan to build a three-story mall complex, dubbed 'Java World'.[26]

On 21 January 1985, nine stupas were badly damaged by nine bombs.[27] In 1991, a blind Muslim evangelist, Husein Ali Al Habsyie, was sentenced to life imprisonment for masterminding a series of bombings in the mid 1980s including the temple attack.[28] Two other members of a right-wing extremist group that carried out the bombings were each sentenced to 20 years in 1986 and another man received a 13-year prison term. On 27 May 2006, an earthquake of 6.2 magnitude on Richter scale struck the south coast of Central Java. The event had caused severe damage around the region and casualties to the nearby city of Yogyakarta, but Borobudur, however, was intact.[29]

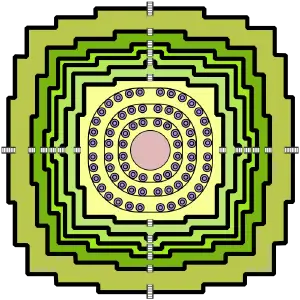

Architecture

Borobudur is built as a single large stupa, and when viewed from above takes the form of a giant tantric Buddhist mandala, simultaneously representing the Buddhist cosmology and the nature of mind.[30] The foundation is a square, approximately 118 metres (387 ft) on each side. It has nine platforms, of which the lower six are square and the upper three are circular. The upper platform features seventy-two small stupas surrounding one large central stupa. Each stupa is bell-shaped and pierced by numerous decorative openings. Statues of the Buddha sit inside the pierced enclosures.

Approximately 55,000 m³ (almost 2 million cubic feet) of stones were taken from neighbouring rivers to build the monument.[31] The stone was cut to size, transported to the site and laid without mortar. Knobs, indentations and dovetails were used to form joints between stones. Reliefs were created in-situ after the building had been completed. The monument is equipped with a good drainage system to cater for the area's high stormwater run-off. To avoid innundation, 100 spouts are provided at each corner with a unique carved gargoyles (makaras).

Borobudur differs markedly with the general design of other structures built for this purpose. Instead of building on a flat surface, Borobudur is built on a natural hill. The building technique is, however, similar to other temples in Java. With no inner space as in other temples and its general design similar to the shape of pyramid, Borobudur was first thought more likely to have served as a stupa, instead of a temple (or candi in Indonesian).[31] A stupa is intended as a shrine for the Lord Buddha. Sometimes stupas were built only as devotional symbols of Buddhism. A temple, on the other hand, is used as a house of deity and have inner spaces for worship. The complexity, however, of the monument's meticulous design suggests it is in fact a temple. Congregational worship in Borobudur is performed by means of pilgrimage. Pilgrims were guided by the system of staircases and corridors ascending to the top platform. Each platform represents one stage of enlightment. The path that guides pilgrims was designed with the symbolism of sacred knowledge according to the Buddhism cosmology.[32]

Little is known about the architect Gunadharma.[33] His name is actually recounted from Javanese legendary folk tales rather than written in old inscriptions. He was said to be one who "... bears the measuring rod, knows division and thinks himself composed of parts."[33] The basic unit measurement he used during the construction was called tala, defined as the length of a human face from the forehead's hairline to the tip of the chin or the distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the middle finger when both fingers are stretched at their maximum distance.[34] The unit metrics is then obviously relative between persons, but the monument has exact measurements. A survey conducted in 1977 revealed frequent findings of a ratio of 4:6:9 around the monument. The architect had used the formula to lay out the precise dimensions of Borobudur.[34] The identical ratio formula was further found in the nearby Buddhist temples of Pawon and Mendhut. Archeologists conjectured the purpose of the ratio formula and the tala dimension has calendrical, astronomical and cosmological themes, as of the case in other Buddhist temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia.[33]

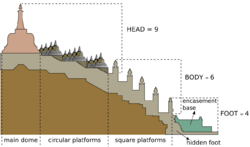

The main vertical structure can be divided into three groups: base (or foot), body, and top, which resembles the three major division of a human body.[33] The base is a 123x123 m² square in size and 4 metres (13 ft) high of walls.[31] The body is composed of five square platforms each with diminishing heights. The first terrace is set back 7 metres (23 ft) from the edge of the base. The other terraces are set back by 2 metres (6.5 ft), leaving a narrow corridor at each stage. The top consists of 3 circular platforms, with each stage supporting a row of perforated stupas, arranged in concentric circles. There is one main dome at the center; the top of which is the highest point of the monument (35 metres or 115 ft above ground level). Access to the upper part is through stairways at the centre of each side with a number of gates, watched by a total of 32 lion statues. The main entrance is at the eastern side, the location of the first narrative reliefs. On the slopes of the hill, there are also stairways linking the monument to the low-lying plain.

The three monument's division symbolizes three stages of mental preparation towards the ultimate goal according to the Buddhism cosmology, namely Kamadhatu (the world of desires), Rupadhatu (the world of forms), and finally Arupadhatu (the formless world).[35] Kamadhatu is represented by the base, Rupadhatu by the five square platforms (the body), and Arupadhatu by the three circular platforms and the large topmost stupa. The architectural features between three stages have methaporical differences. For instance, square and detailed decorations in the Rupadhatu disappear into plainless circular platforms in the Arupadhatu to represent how the world of forms - where men are still attached with forms and names - changes into the world of the formless.[36]

In 1885, a hidden structure under the base was accidentally discovered.[37] The "hidden foot" contains reliefs, 160 of which are narrative describing the real Kamadhatu. The remaining reliefs are panels with short inscriptions that apparently describe instruction for the sculptors, illustrating the scene to be carved.[38] An encasement base hides the real base of which its functions remains a mystery. It was first thought that the real base had to be covered to prevent a disastrous subsidence of the monument through the hill.[38] There is another theory that the encasement base was added because the original hidden foot was incorrectly designed, according to Vastu Shastra, the Indian ancient book about architecture and town planning.[37] The encasement base, however, was built with detailed and meticulous design with aesthetics and religious compensation.

Reliefs

| Narrative Panels Distribution[39] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| section | location | story | #panels |

| hidden foot | wall | Karmavibhangga | 160 |

| first gallery | main wall | Lalitavistara | 120 |

| Jataka/Avadana | 120 | ||

| balustrade | Jataka/Avadana | 372 | |

| Jataka/Avadana | 128 | ||

| second gallery | main wall | Gandavyuha | 128 |

| ballustrade | Jataka/Avadana | 100 | |

| third gallery | main wall | Gandavyuha | 88 |

| ballustrade | Gandavyuha | 88 | |

| fourth gallery | main wall | Gandavyuha | 84 |

| ballustrade | Gandavyuha | 72 | |

| Total | 1,460 | ||

Borobudur contains approximately 2,670 individual bas reliefs (1,460 narrative and 1,212 decorative panels), which cover the façades and balustrades. The total relief surface is 2,500 m² and they are distributed at the hidden foot (Kamadhatu) and the five square platforms (Rupadhatu).[39]

The narrative panels, which tell the story of Sudhana and Manohara,[40] are grouped into 11 series encircled the monument with the total length of 3,000 metres (1.86 miles). The hidden foot contains the first series with 160 narrative panels and the remaining 10 series are distributed throughout walls and balustrades in four galleries starting from the eastern entrance stairway to the left. Narrative panels on the wall read from right to left, while on the balustrade read from left to right. This conforms with pradaksina, the ritual of circumambulation performed by pilgrims who move in a clockwise direction while keeping the sanctuary to their right.[41]

The hidden foot depicts the story of the karma law. The walls of the first gallery have two superimposed series of reliefs; each consists of 120 panels. The upper part depicts the biography of Buddha, while the lower part of the wall and also ballustrades in the first and the second galleries tell the story of Buddha's former lives.[39] The remaining panels are devoted to Sudhana's further wandering about his search; terminated by his attainment of the Perfect Wisdom.

The law of karma (Karmavibhangga)

The 160 hidden panels do not form a continuous story, but each panel provides one complete illustration of cause and effect.[39] There are depictions of blameworthy activities, from gossip to murder, with their corresponding punishments. There are also praiseworthy activities, that include charity and pilgrimage to sanctuaries, and their subsequent rewards. The pains of hell and the pleasure of heaven are also illustrated. There are scenes of daily life, complete with the full panorama of samsara (the endless cycle of birth and death).

The birth of Buddha (Lalitavistara)

The story starts from the glorious descent of the Lord Buddha from the Tushita heaven, and ends with his first sermon in the Deer Park near Benares.[41] The relief shows the birth of Buddha as Prince Siddharta, son of King Suddhodana and Queen Maya of Kapilavastu (in present-day Nepal).

The story is preceded by 27 panels showing various preparations, in heavens and on earth, to welcome the final incarnation of Bodhisattva.[41] Before descending from Tushita heaven, Bodhisattva entrusted his crown to his successor, the future Buddha Maitreya. He descended on earth in the shape of white elephants with six tusks, penetrated to Queen Maya's right womb. Queen Maya had a dream of this event, which was interpreted that his son would become either a sovereign or a Buddha.

While Queen Maya felt that it was the time to give the birth, she went to the Lumbini park outside the Kapilavastu city. She stood under a plaksa tree, holding one branch with her right hand and she gave birth to a son, Prince Siddharta. The story on the panels continues until the prince became Buddha.

Prince Siddharta story (Jataka) and other legendary persons (Avadana)

Jatakas are stories about the Buddha before he was born as Prince Siddharta.[42] Avadanas are similar with jatakas, but the main figure is not Bodhisattva himself. The saintly deeds in avadanas are attributed to other legendary persons. Jatakas and avadanas are treated in one and the same series in the reliefs of Borobudur.

The first 20 lower panels in the first gallery on the wall depict the Sudhanakumaravadana or the saintly deeds of Prince Sudhanakumara. The first 135 upper panels in the same gallery on the balustrades are devoted to the 34 legends of the Jatakamala.[43] The remaining 237 panels depict stories from other sources, as do for the lower series and panels in the second gallery. Some jatakas stories are depicted twice, for example the story of King Sibhi.

Sudhana search of the Ultimate Truth (Gandavyuha)

Gandavyuha is a story about Sudhana's tireless wandering in search of the Highest Perfect Wisdom. It covers two galleries (third and fourth) and also half of the second gallery; comprising in total of 460 panels.[44] The principal figure of the story, the youth Sudhana, son of an extremely rich merchant, appears on the 16th panel. The preceding 15 panels form a prologue to the story of the miracles during Buddha's samadhi in the Garden of Jeta at Sravasti.

During his search, Sudhana visited no less than 30 teachers but none of them had satisfied him completely. He was then instructed by Manjusri to meet the monk Megasri, where he was given the first doctrine. Sudhana journey continues to meet in the following order Supratisthita, the physician Megha (Spirit of Knowledge), the banker Muktaka, the monk Saradhvaja, the upasika Asa (Spirit of Supreme Enlightment), Bhismottaranirghosa, the Brahmin Jayosmayatna, Princess Maitrayani, the monk Sudarsana, a boy called Indriyesvara, the upasika Prabhuta, the banker Ratnachuda, King Anala, the god Siva Mahadeva, Queen Maya, Bodhisattva Maitreya and then back to Manjusri. Each meeting has given Sudhana a specific doctrine, knowledge and wisdom. These meetings are shown in the third gallery.

After the last meeting with Manjusri, Sudhana went to the residence of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra; depicted in the fourth gallery. The entire series of the fourth gallery is devoted to the teaching of Samantabhadra. The narrative panels finally end with the Sudhana's achievement of the Supreme Knowledge and the Ultimate Truth.[45]

Buddha statues

Apart from the story of Buddhist cosmology carved in stones, Borobudur has many Buddha statues. The cross-legged Buddha statues are seated with lotus position. They are distributed on the five square platforms (the Rupadhatu level) and on the top platform (the Arupadhatu level).

The Buddha statues are in niches at the Rupadhatu level, arranged in rows on the outer sides of the balustrades. As platforms progressively diminish to the upper level, the number of Buddha statues are decreasing. The first balustrades have 104 niches, the second 104, the third 88, the fourth 72 and the fifth 64. In total, there are 432 Buddha status at the Rupadhatu level.[1] At the Arupadhatu level (or the three circular platforms), Buddha statues are placed inside perforated stupas. The first circular platform has 32 stupas, the second 24 and the third 16, that sum up to 72 stupas.[1] Of the total 504 Buddha statues, over 300 are mutilated (mostly headless) and 43 are completely missing.

At glance, all Buddha statues are equal, but there is subtle difference between them in the mudras or the position of the hands. There are 5 groups of mudra: North, East, South, West and Zenith, which represent the five cardinal compass according to Mahayana. The first four balustrades have the first four mudras: North, East, South and West, of which Buddha statues that face one compass direction has the corresponding mudra. Buddha statues at the fifth balustrades and inside the 72 stupas on the top platform have the same mudra: Zenith. Each mudra represent one of the Five Dhyani Buddhas; each has its own symbolism.[46] They are Abhaya mudra for Amogashiddi (north), Vara mudra for Ratnasambhava (south), Dhyana mudra for Amitabha (west), Bhumisparsa mudra for Aksobhya (east) and Dharmachakra mudra for Vairochana (zenith).

Restoration

Borobudur attracted attention in 1885, when Yzerman, the Chairman of the Archaeological Society in Yogyakarta, made a discovery about the hidden foot.[37] Photographs that reveal reliefs on the hidden foot were made in 1890–1891.[47] The discovery has led the Dutch East Indies government to take a necessary step to safeguard the monument. In 1900, the government set up a commission consisted of three officials to assess the monument: Brandes, an art historian, Theodoor van Erp, a Dutch army engineer officer, and Van de Kamer, a construction engineer from the Department of Public Works.

In 1902, the commission submitted a threefold plan of proposal to the government. First, the immediate dangers should be avoided by resetting the corners, removing stones that endangers the adjacent parts, strengthening the first balustrades and restoring several niches, archways, stupas and the main dome. Second, fencing off the courtyards, providing proper maintenance and improving drainage by restoring floors and spouts. Third, all loose stones should be removed, cleared up the monument up to the first balustrades, removed disfigured stones and restored the main dome. The total cost was estimated at that time around 48,800 Dutch guilders.

The restoration then was carried out between 1907–1911, using the principles of anastylosis and led by Theodor van Erp.[48] The first seven months of his restoration was excavating the grounds around the monument to find missing Buddha heads and panel stones. Van Erp dismantled and rebuilt the upper three circular platforms and stupas. Along the way, Van Erp discovered more things to improve the monument that he submitted another proposal that was agreed with the additional cost of 34,600 guilders. At first glance Borobudur had been restored to its old glory.

Due to the limited budget, the restoration had been primarily focused on cleaning the sculptures, but Van Erp did not solve the drainage problem. Within fifteen years, the gallery walls were sagging and the reliefs showed signs of new cracks and deterioration.[48] Van Erp used concrete from which alkali salts and calcium hydroxide are leached and transported into the rest of the construction. This has caused some problems that a further thorough renovation is urgently needed.

Small restorations have been performed since then, but not for a complete protection. In the late 1960s, the Indonesian government had requested a major renovation to protect the monument to the international community. In 1973, a master plan to restore Borobudur was created.[23] The Indonesian government and UNESCO then undertook the complete overhaul of the monument in a big restoration project between 1975–1982.[48] The foundation was stabilized and all 1,460 panels were cleaned. The restoration involved the dismantling of the five square platforms and improved the drainage by embedding water channels into the monument. Both impermeable and filter layers were added. This colossal project involved around 600 people to restore the monument and cost in total of US$ 6,901,243.[49] After the renovation was finished, UNESCO listed Borobudur as a World Heritage Site in 1991.[50]

See also

- Candi of Indonesia

- History of Buddhism

- Indonesian architecture

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

General References

- Parmono Atmadi (1988). Some Architectural Design Principles of Temples in Java: A study through the buildings projection on the reliefs of Borobudur temple. Yogyakarta: Gajah Mada University Press. ISBN 979-420-085-9.

- Jacques Dumarçay (1991). Borobudur, trans. and ed. by Michael Smithies, 2nd ed., Singapore: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-588550-3.

- John Miksic (1990). Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas. Boston: Shambala. ISBN 0-87773-906-4.

- Soekmono (1976). "Chandi Borobudur - A Monument of Mankind". The Unesco Press, Paris. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- R. Soekmono, J.G. de Casparis, J. Dumarçay, P. Amranand and P. Schoppert (1990). Borobudur: A Prayer in Stone. Singapore: Archipelago Press. ISBN 2-87868-004-9.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Soekmono (1976), page 35-36.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Soekmono (1976), page 4.

- ↑ Borobudur Temple Compounds. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ (November 2003) Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd, p.211-215. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Mark P. Hampton (2005). Heritage, Local Communities and Economic Development. Annals of Tourism Research 32 (3): 735–759.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 E. Sedyawati (1997). W. Nuryanti (ed.) "Potential and Challenges of Tourism: Managing the National Cultural Heritage of Indonesia". Tourism and Heritage Management, 25–35, Yogyakarta: Gajah Mada University Press.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Soekmono (1976), page 13.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Thomas Stamford Raffles (1817). The History of Java, 1978, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580347-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Soekmono (1976), page 1.

- ↑ N. J. Krom (1927). Borobudur, Archaelogical Description. The Hague: Nijhoff. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Murwanto, H.; Gunnell, Y; Suharsono, S.; Sutikno, S. and Lavigne, F (2004). Borobudur monument (Java, Indonesia) stood by a natural lake: chronostratigraphic evidence and historical implications. The Holocene (3): 459–463.

- ↑ R.W. van Bemmelen (1949). The geology of Indonesia, general geology of Indonesia and adjacent archipelago, vol 1A, The Hague, Government Printing Office, Martinus Nijhoff. cited in Murwanto (2004).

- ↑ Newhall C.G., Bronto S., Alloway B., Banks N.G., Bahar I., del Marmol M.A., Hadisantono R.D., Holcomb R.T., McGeehin J., Miksic J.N., Rubin M., Sayudi S.D., Sukhyar R., Andreastuti S., Tilling R.I., Torley R., Trimble D., and Wirakusumah A.D. (2000). 10,000 Years of explosive eruptions of Merapi Volcano, Central Java: archaeological and modern implications. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 100 (1): 9–50.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Soekmono (1976), page 9.

- ↑ Miksic (1990)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Dumarçay (1991).

- ↑ Paul Michel Munoz (2007). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Didier Millet, p.143. ISBN 9814155675.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Soekmono (1976), page 10.

- ↑ Soekmono (1976), page 3.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Soekmono (1976), page 5.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Soekmono (1976), page 6.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Soekmono (1976), page 42.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Caesar Voute (1973). The Restoration and Conservation Project of Borobudur Temple, Indonesia. Planning: Research: Design. Studies in Conservation 18 (3): 113–130.

- ↑ Coordinating Ministry for Public Welfare. Keputusan Bersama tentang Hari Libur Nasional dan Cuti Bersama tahun 2006. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-12-13.

- ↑ The Meaning of Procession. Waisak. Walubi (Buddhist Council of Indonesia). Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ↑ Jamie James. "Battle of Borobudur", Time, 27 January 2003. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- ↑ "1,100-Year-Old Buddhist Temple Wrecked By Bombs in Indonesia", The Miami Herald, 22 January 1985. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ↑ Harold Crouch (2002). The Key Determinants of Indonesia’s Political Future. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 7. ISSN 0219-3213.

- ↑ Sebastien Berger. "An ancient wonder reduced to rubble", The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ↑ A. Wayman (1981). "Reflections on the Theory of Barabadur as a Mandala". Barabudu History and Significance of a Buddhist Monument, Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Soekmono (1976), page 16.

- ↑ Peter Ferschin and Andreas Gramelhofer (2004). "Architecture as Information Space". 8th Int. Conf. on Information Visualization, 181–186, IEEE.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Caesar Voûte and Mark Long. Borobudur: Pyramid of the Cosmic Buddha. D.K. Printworld Ltd.. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Atmadi (1988).

- ↑ Tartakov, Gary Michael. Lecture 17: Sherman Lee’s History of Far Eastern Art (Indonesia and Cambodja). Lecture notes for Asian Art and Architecture: Art & Design 382/582. Iowa State University. Retrieved 2006-05-21.

- ↑ Soekmono (1976), page 17.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "Borobudur Pernah Salah Design?", Kompas, 7 April 2000. Retrieved 2006-12-13. (written in Indonesian)

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Soekmono (1976), page 18.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Soekmono (1976), page 20.

- ↑ Jaini, P.S. (1966). The Story of Sudhana and Manohara: An Analysis of the Texts and the Borobudur Reliefs. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 29 (3): 533–558. ISSN 0041977X.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Soekmono (1976), page 21.

- ↑ Soekmono (1976), page 26.

- ↑ Soekmono (1976), page 29.

- ↑ Soekmono (1976), page 32.

- ↑ Soekmono (1976), page 35.

- ↑ Roderick S. Bucknell and Martin Stuart-Fox (1995). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. UK: Routledge. ISBN 0700702342.

- ↑ Soekmono (1976), page 43.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 UNESCO (31 August 2004). UNESCO experts mission to Prambanan and Borobudur Heritage Sites. Press release.

- ↑ UNESCO. Cultural heritage and partnership; 1999. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-12-13.

- ↑ Borobudur Temple Compounds. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

Further reading

- Luis O. Gomez and Hiram W. Woodward (1981). Barabudur, history and significance of a Buddhist monument, presented at the Int. Conf. on Borobudur, Univ. of Michigan, May 16-17, 1974, Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press. ISBN 0-89581-151-0.

- August J.B. Kempers (1976). Ageless Borobudur : Buddhist mystery in stone, decay and restoration, Mendut and Pawon, folklife in ancient Java. Wassenaar: Servire. ISBN 90-6077-553-8.

- John Miksic (1999). The Mysteries of Borobudur. Hongkong: Periplus. ISBN 962-593-198-8.

- Adrian Snodgrass (1985). The symbolism of the stupa, Southeast Asia Program, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University. ISBN 0-87727-700-1.

External links

- Official site

- Borobudur travel guide from Wikitravel

- Archaeology and architecture of Borobudur

- 360° view on the World Heritage Tour

- Australia National University's research project on Borobudur

Template:Buddhism2

| |||||||

[[Category:]]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.