Srivijaya

| This article is part of the History of Indonesia series |

|---|

|

| See also: |

| Prehistory |

| Early kingdoms |

| Srivijaya (third to fourteenth centuries) |

| Sailendra (eighth & ninth centuries) |

| Kingdom of Mataram (752–1045) |

| Kediri (1045–1221) |

| Singhasari (1222–1292) |

| Majapahit (1293–1500) |

| The rise of Muslim states |

| The spread of Islam (1200–1600) |

| Malacca Sultanate (1400–1511) |

| Sultanate of Demak (1475–1518) |

| Aceh Sultanate (1496 - 1903) |

| Mataram Sultanate (1500s to 1700s) |

| Colonial Indonesia |

| The Portuguese in Indonesia (1512-1850) |

| Dutch East India Company (1602–1799) |

| Dutch East Indies (1800–1942) |

| The emergence of Indonesia |

| National Revival (1899–1942) |

| Japanese Occupation (1942-45) |

| Declaration of Independence (1945) |

| National Revolution (1945–1950) |

| Independent Indonesia |

| Liberal Democracy (1950-1957) |

| Guided Democracy (1957-1965) |

| Transition to the New Order (1965–1966) |

| The New Order (1966-1998) |

| Reformation Era (1998–present) |

| [Edit this template] |

Srivijaya, Sriwijaya, Shri Bhoja, Sri Boja or Shri Vijaya (200s - 1300s[1]) was an ancient Malay kingdom on the island of Sumatra which influenced much of the Malay Archipelago. Records of its beginning are scarce, and estimations of its origins range from the third to fifth centuries, but the earliest solid proof of its existence dates from the seventh century; a Chinese monk, I-Tsing, wrote that he visited Srivijaya in 671 for six months and studied at a Buddhist temple there;[2][3]and the Kedukan Bukit Inscription containing its name is dated 683.[4] The kingdom ceased to exist between 1200 and 1300 due to various factors, including the expansion of Majapahit in Java.[1] In Sanskrit, sri means "shining" or "radiant" and vijaya means "victory" or "excellence." [5]

After it fell it was largely forgotten, and was largely unknown to modern scholars until 1918 when French historian George Coedès of the École française d'Extrême-Orient postulated the existence of a Srivijayan empire based in Palembang.[5] Around 1992 and 1993, Pierre-Yves Manguin proved that the centre of Srivijaya was along the Musi River between Bukit Seguntang and Sabokingking (situated in what is now the province of South Sumatra, Indonesia).[5]

Historiography and Legacy

There is no continuous knowledge of Srivijaya in Indonesian histories; its forgotten past has been recreated by foreign scholars. No modern Indonesians, not even those of the Palembang area around which the kingdom was based, had heard of Srivijaya until the 1920s, when French scholar and epigraphist George Coedès published his discoveries and interpretations in Dutch and Indonesian-language newspapers.[6] Coedès noted that the Chinese references to "Sanfoqi," previously read as "Sribhoja," and the inscriptions in Old Malay refer to the same empire.[7]

In 1918, George Coedès linked a large maritime state identified in seventh-century Chinese sources as Shilifoshih, and described in later Indian and Arabic texts, to a group of stone inscriptions written in Old Malay which told about the foundation of a polity named Srivijaya, for which Shilifoshih was a regular Chinese transcription. These inscriptions were all dated between 683 and 686, and had been found around the city of Palembang, on Sumatra. A few Hindu and Buddhist statues had been found in the region, but there was little archaeological evidence to document the existence of a large state with a wealthy and prestigious ruler and a center of Buddhist scholarship. Such evidence was found at other sites on the isthmus of the Malay Peninsula, and suggested that they may have been the capital of Srivijaya. Finally, in the 1980s, enough archaeological evidence was found in Southern Sumatra and around Palembang to support Coedès' theory that a large trading settlement, with manufacturing, religious, commercial and political centers, had existed there for several centuries prior to the fourteenth century. Most of the information about Srivijaya has been deduced from these archaeological finds, plus stone inscriptions found in Sumatra, Java, and Malaysia, and the historical records and diaries of Arab and Chinese traders and Buddhist travelers.[8]

Srivijaya and by extension Sumatra had been known by different names to different peoples. The Chinese called it Sanfotsi or San Fo Qi, and at one time there was an even older kingdom of Kantoli that could be considered as the predecessor of Srivijaya.[9] In Sanskrit and Pali, it was referred to as Yavadesh and Javadeh respectively. The Arabs called it Zabag and the Khmer called it Melayu. The confusion over names is another reason why the discovery of Srivijaya was so difficult.[9] While some of these names are strongly reminiscent of the name of Java, there is a distinct possibility that they may have referred to Sumatra instead.[10]

Formation and growth

Little physical evidence of Srivijaya remains.[11] According to the Kedukan Bukit Inscription, the empire of Srivijaya was founded by Dapunta Hyang Çri Yacanaca (Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa). He led twenty thousand troops (mainly land troopers and a few hundred ships) from Minanga Tamwan (speculated to be Minangkabau) to Palembang, Jambi, and Bengkulu.

The empire was a coastal trading centre and was a thalassocracy (sea-based empire). It did not extend its influence far beyond the coastal areas of the islands of Southeast Asia, with the exception of contributing to the population of Madagascar 3,300 miles to the west. Around the year 500, Srivijayan roots began to develop around present-day Palembang, Sumatra, in modern Indonesia. The empire was organized in three main zones—the estuarine capital region centred on Palembang, the Musi River basin which served as hinterland, and rival estuarine areas capable of forming rival power centers. The areas upstream of the Musi river were rich in various commodities valuable to Chinese traders.[12] The capital was administered directly by the ruler while the hinterland remained under its own local datus or chiefs, who were organized into a network of allegiance to the Srivijaya maharaja or king. Force was the dominant element in the empire's relations with rival river systems such as the Batang Hari, which centered in Jambi. The ruling lineage intermarried with the Sailendras of Central Java.

Under the leadership of Jayanasa, the kingdom of Malayu became the first kingdom to be integrated into the Srivijayan Empire. This possibly occurred in the 680s. Malayu, also known as Jambi, was rich in gold and was held in high esteem. Srivijaya recognized that the submission of Malayu to them would increase their own prestige.[13]

Chinese records dated in the late seventh century mention two Sumatran kingdoms as well as three other kingdoms on Java as being part of Srivijaya. By the end of the eighth century, many Javanese kingdoms, such as Tarumanagara and Holing, were within the Srivijayan sphere of influence. It has also been recorded that a Buddhist family related to Srivijaya, probably the Sailendras[14], dominated central Java at that time. According to the Kota Kapur Inscription, the empire conquered Southern Sumatra as far as Lampung. The empire thus grew to control the trade on the Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea and Karimata Strait.

During the same century, Langkasuka on the Malay Peninsula became part of Srivijaya.[15] Soon after this, Pan Pan and Trambralinga, which were located north of Langkasuka, came under Srivijayan influence. These kingdoms on the peninsula were major trading nations that transported goods across the peninsula's isthmus.

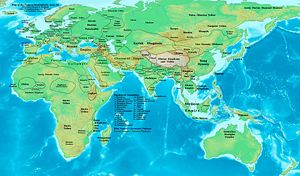

With the expansion to Java as well as the Malay Peninsula, Srivijaya controlled two major trade choke points in Southeast Asia. Some Srivijayan temple ruins are observable in Thailand, Cambodia and on the Malay Peninsula.

At some point in the seventh century, Cham ports in eastern Indochina started to attract traders, diverting the flow of trade from Srivijaya. In an effort to redirect the flow of trade back to Srivijaya, the Srivijayan king or maharaja, Dharmasetu, launched various raids against the coastal cities of Indochina. The city of Indrapura by the Mekong River was temporarily controlled from Palembang in the early eighth century.[14] The Srivijayans continued to dominate areas around present-day Cambodia until the Khmer King Jayavarman II, the founder of the Khmer Empire dynasty, severed the Srivijayan link later in the same century.[16]

After Dharmasetu, Samaratungga, the last ruler of the Sailendra dynasty, married Dharmasetu’s daughter, Dewi Tara, the princess of Srivijaya, and became the next Maharaja of Srivijaya. He reigned as ruler from 792 to 835. Unlike the expansionist Dharmasetu, Samaratuga did not indulge in military expansion, but preferred to strengthen the Srivijayan hold of Java. He personally oversaw the construction of Borobudur; the temple was completed in 825, during his reign.[17]

By the twelfth century, the Srivijyan kingdom included parts of Sumatra, Ceylon, the Malay Peninsula, Western Java, Sulawesi, the Moluccas, Borneo and the Philippines, most notably the Sulu Archipelago and the Visayas islands (the latter island group, as well as its population, is named after the empire).[18]

Srivijaya remained a formidable sea power until the thirteenth century.[1]

Vajrayana Buddhism

A stronghold of Vajrayana Buddhism, Srivijaya attracted pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. These included the Chinese monk Yijing, who made several lengthy visits to Sumatra on his way to study at Nalanda University in India in 671 and 695, and the eleventh century Bengali Buddhist scholar Atisha, who played a major role in the development of Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet. In the year 687, Yi Jing stopped in the kingdom of Srivijaya on his way back to Tang (China), and stayed there for two years to translate original Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures to Chinese. In the year 689 he returned to Guangzhou to obtain ink and papers and returned again to Srivijaya the same year. Yijing reports that the kingdom was home to more than a thousand Buddhist scholars; it was in Srivijaya that he wrote his memoir of Buddhism during his own lifetime. Travelers to these islands mentioned that gold coinage was in use on the coasts, but not inland.

Relationship with Regional Powers

During the sixth and seventh centuries, the reunification of China under the Sui (590 – 618) and T’ang dynasties, and the demise of long-distance trade with Persia, created new opportunity for Southeast Asian traders.[19] Although historical records and archaeological evidence are scarce, it appears that by the seventh century, Srivijaya had established suzerainty over large areas of Sumatra, western Java and much of the Malay Peninsula. Dominating the Malacca and Sunda straits, Srivijaya controlled both the spice route traffic and local trade, charging a toll on passing ships. Serving as an entrepôt for Chinese, Malay, and Indian markets, the port of Palembang, accessible from the coast by way of a river, accumulated great wealth. Envoys traveled to and from China frequently.

The domination of the region through trade and conquest in the seventh and ninth centuries began with the absorption of the first rival power center, the Jambi kingdom. Jambi's gold mines were a crucial economic resource and may be the origin of the word Suvarnadvipa (island of gold), the Sanskrit name for Sumatra. Srivijaya helped spread the Malay culture throughout Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and western Borneo. Srivijaya's influence waned in the eleventh century, as it came into frequent conflict with, and was ultimately subjugated by, Javanese kingdoms, first Singhasari and then Majapahit. The seat of the empire moved to Jambi in the last centuries of Srivijaya's existence.

Some historians claim that Chaiya in the Surat Thani province in Southern Thailand was at least temporarily the capital of Srivijaya, but this claim is widely disputed. However, Chaiya was probably a regional center of the kingdom. The temple of Borom That in Chaiya contains a reconstructed pagoda in Srivijaya style. The Khmer Empire may also have been a tributary in its early stages.

Srivijaya also maintained close relations with the Pala Empire in Bengal, and an 860 inscription records that the maharaja of Srivijaya dedicated a monastery at the Nalanda university in Pala territory. Relations with the Chola dynasty of southern India were initially friendly but deteriorated into actual warfare in the eleventh century.

Golden Age

After trade disruption at Canton between 820 and 850, the ruler of Jambi was able to assert enough independence to send missions to China in 853 and 871. Jambi's independence coincided with the troubled time when the Sailendran Balaputra, expelled from Java, seized the throne of Srivijaya. The new maharaja was able to dispatch a tributary mission to China by 902. Only two years later, the expiring Tang Dynasty conferred a title on a Srivijayan envoy.

In the first half of the tenth century, between the fall of Tang Dynasty and the rise of Song, there was brisk trade between the overseas world and the Fujian kingdom of Min and the rich Guangdong kingdom of Nan Han. Srivijaya undoubtedly benefited from this, in anticipation of the prosperity it was to enjoy under the early Song. Around 903, the Persian explorer and geographer Ibn Rustah who wrote extensively of his travels was so impressed with the wealth of Srivijaya's ruler that he declared one would not hear of a king who was richer, stronger or with more revenue. The main urban centers were at Palembang (especially the Bukit Seguntang area), Muara Jambi and Kedah.

Decline

In 1025, Rajendra Chola, the Chola king from Coromandel in South India, conquered Kedah from Srivijaya and occupied it for some time. The Cholas continued a series of raids and conquests throughout what is now Indonesia and Malaysia for the next 20 years. Although the Chola invasion was ultimately unsuccessful, it gravely weakened the Srivijayan hegemony and enabled the formation of regional kingdoms based, like Kediri, on intensive agriculture rather than coastal and long-distance trade.

Between 1079 and 1088, Chinese records show that Srivijaya sent ambassadors from Jambi and Palembang. In 1079 in particular, an ambassador from Jambi and Palembang each visited China. Jambi sent two more ambassadors to China in 1082 and 1088. This suggests that the center of Srivijaya frequently shifted between the two major cities during that period.[20] The Chola expedition as well as changing trade routes weakened Palembang, allowing Jambi to take the leadership of Srivijaya from the eleventh century on.[21]

In 1288, Singhasari conquered Palembang, Jambi and much of Srivijaya during the Pamalayu expedition.

In the year 1293, Majapahit ruled much of Sumatra as the successor of Singhasari. Prince Adityawarman was given responsibilities over Sumatra in 1347 by Hayam Wuruk, the fourth king of Majapahit. A rebellion in 1377 was suppressed by Majapahit but it left the area of southern Sumatra in chaos and desolation.

In the following years, sedimentation on the Musi river estuary cut the kingdom's capital off from direct sea access. This strategic disadvantage crippled the trade in the Kingdom's capital. As the decline continued, Islam made its way to the Aceh region of Sumatra, spreading through contacts with Arab and Indian traders. By the late thirteenth century, the kingdom of Pasai in northern Sumatra converted to Islam. At the same time, Srivijaya was briefly a tributary state of the Khmer Empire and later the Sukhothai kingdom. The last inscription, on which a crown prince, Ananggavarman, son of Adityawarman, is mentioned, dates from 1374.

By 1402, Parameswara (the great-great-grandson of Raden Wijaya, the first king of Majapahit), the last prince of Srivijaya had founded the Sultanate of Malacca on the Malay peninsula.

Commerce

In the world of commerce, Srivijaya rapidly rose to be a far-flung empire controlling the two passages between India and China, the Sunda Strait from Palembang and the Malacca straits from Kedah. Arab accounts state that the empire of the maharaja was so vast that in two years the swiftest vessel could not travel round all its islands, which produced camphor, aloes, cloves, sandal-wood, nutmegs, cardamom and crubebs, ivory, gold and tin, making the maharaja as rich as any king in the Indies.

Legacy

Once the existence of Srivijaya had been established, it became a symbol of early Sumatran greatness, and a great empire to balance Java's Majapahit in the east. In the twentieth century, both empires were referred to by Indonesian nationalist intellectuals to argue for an Indonesian identity within and Indonesian state prior to the establishment of the Dutch colonial state.[6]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Paul Michel Munoz. Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006. ISBN 9814155675), 171

- ↑ Munoz, 122

- ↑ Sabri Zain, Sejarah Melayu, Buddhist Empires. A History of the Malay Peninsula. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox, Darrell Tryon. Chapter 15. "Indic Transformation: The Sanskritization of Jawa and the Javanization of the Bharata." The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. 1995, [1]. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Munoz, 117

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jean Gelman Taylor. Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. (New Haven; and London: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0300105185), 8-9

- ↑ N.J. Krom. Chapter: "Het Hindoe-tijdperk" Geschiedenis van Nederlandsch Indië, edited by F.W. Stapel. (Amsterdam: N.V. U.M. Joost van den Vondel, 1938), vol. I, 149

- ↑ En, 1246

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Munoz, 102, 114

- ↑ N.J. Krom. Het oude Java en zijn kunst, 2nd ed. (Haarlem: Erven F. Bohn N.V. 1943), 12

- ↑ Taylor, 29

- ↑ Munoz, 113

- ↑ Munoz, 124

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Munoz, 132

- ↑ Munoz, 130

- ↑ Munoz, 140

- ↑ Munoz, 143

- ↑ Jainal D. Rasul. Agonies and Dreams: The Filipino Muslims and Other Minorities. (Quezon City: CARE Minorities. 2003), 77

- ↑ Southeast Asia a historical encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. (Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2004), 1245

- ↑ Munoz, 165

- ↑ Munoz, 167

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hall, D. G. E. 1964. A history of South-east Asia. London: Macmillan.

- Krom, N.J. Het oude Java en zijn kunst, 2nd ed. (Haarlem: Erven F. Bohn N.V. 1943.

- Munoz, Paul Michel. Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006. ISBN 9814155675.

- Ooi, Keat Gin. 2004. Southeast Asia a historical encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576077705, 1245 - 1248

- Rasul, Jainal D. Agonies and Dreams: The Filipino Muslims and Other Minorities. Quezon City: CARE Minorities. 2003.

- SarDesai, D. R. 1989. Southeast Asia, past & present. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0813304458.

- Shaffer, Lynda. 1996. Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. Sources and studies in world history. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563241439.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. 2003. A short history of China and southeast Asia tribute, trade and influence. Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1741150906

- Taylor, Jean Gelman. Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven; and London: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0300105185.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.