Mandala

A Mandala (Sanskrit maṇḍala मंडलः "circle," "completion") refers to a sacred geometric device commonly used in the religious practice of Hinduism and Tibetan Buddhism. It serves several religious purposes including establishing a sacred space and as an aid to meditation and trance induction, focusing attention of aspirants and adepts, an abode of a Buddha or bodhisattva, a symbolic map of the universe, and pathway to liberation. Mandala has become a generic term for any plan, chart, or geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically, a microcosm of the Universe from the human perspective.

The mandala's symbolic nature can help one "to access progressively deeper levels of the unconscious, ultimately assisting the meditator to experience a mystical sense of oneness with the ultimate unity from which the cosmos in all its manifold forms arises."[1] The psychoanalyst Carl Jung saw the mandala as "a representation of the unconscious self,"[2] and believed his paintings of mandalas enabled him to identify emotional disorders and work towards wholeness in personality.[3]

Mandalas are particularly important in the Tibetan branch of Vajrayana Buddhism, where they are used in Kalachakra initiation ceremonies, and among other things teach impermanence.

Etymology

The Sanskrit word “Mandala “ is a compound deriving from manda, which means "essence," and the suffix la, meaning "container" or "possessor." Consequently, the etymology of the word "mandala" suggests not just a circle but a "container of essence."[4]

In Hinduism

Religious use

A Hindu temple's ground floor plan often takes the form of a mandala symbolizing the universe. The lotus is sacred not only because it transcends the darkness of the water and mud where its roots are, but also because of its perfectly symmetrical petals, which resemble a mandala.[5]

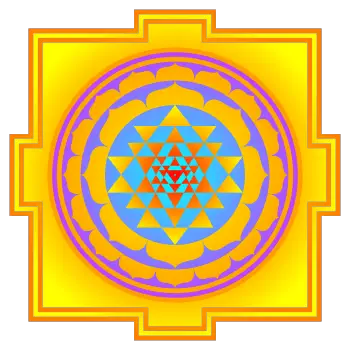

Yantra is a Sanskrit word that is derived from the root meaning "to restrain, curb, check."[6][7] Meanings for the noun derived from this root include "that which restrains or fastens, any prop or support," "a fetter," "any instrument or machine," "an amulet, a mystical or astronomical diagram used as an amulet."[6][8]

Some Hindu esoteric practitioners employ yantra, mantra and other items in their sadhana, puja and yajna.[9]

Yantra, or other permutations and cognate phenomena such as Mandala, Rangoli, Kolam, Rangavalli and other sacred geometrical traditions, are endemic throughout Dharmic Traditions.

A Yantra can be viewed as an astronomical map or diagram representing the astronomical position of the planets over a given date and time. It is considered auspicious in Hindu mythology. These yantras are made up on various objects i.e. Paper, Precious stones, Metal Plates and alloys. It is believed that if we, as humans, follow the basic principal of constantly concentrating on the representation, it helps you build Fortunes, as planets above have their peculiar Gravity which governs basic emotions and karma, derived to attain satisfaction. These yantras are basically made on a particular date and time depending on the prescribed procedures defined under vedas.

Yantra in Sanskrit denotes "loom," "instrument" and "machine." Yantra is an aniconic temenos or tabernacle of deva, asura, genius loci or other archetypal entity. Yantra are theurgical device that engender entelecheia. Yantra are realized by sadhu through darshana and samyama. There are numerous yantra. Shri Yantra is often furnished as an example. Yantra contain geometric items and archetypal shapes and patterns, namely—squares, triangles, circles and floral patterns; but may also include bija mantra and more complex and detailed symbols. Bindu is central, core and instrumental to yantra. Yantra function as revelatory conduits of cosmic truths. Yantra, as instrument and spiritual technology, may be appropriately envisioned as prototypical and esoteric concept mapping machines or conceptual looms. Certain yantra are held to embody the energetic signatures of, for example, the Universe, consciousness, ishta-devata. Some Hindu esoteric practitioners employ yantra, mantra and other items of the saṃdhyā-bhāṣā (Bucknell, et al.; 1986: ix) in their sadhana, puja and yajna. Though often rendered in two dimensions through art, yantra are conceived and conceptualised by practitioners as multi-dimensional sacred architecture and in this quality are identical with their correlate the mandala. Meditation and trance induction with Yantra are invested in the various lineages of their transmission as instruments that potentiate the accretion and manifestation of siddhi.

Madhu Khanna, in linking Mantra, Yantra, Ishta-devata, and thoughtforms states:

Mantras, the Sanskrit syllables inscribed on yantras, are essentially 'thought forms' representing divinities or cosmic powers, which exert their influence by means of sound-vibrations.[10]

Political use

Mandala means "circle of kings." The mandala is a model for describing the patterns of diffuse political power in early Southeast Asian history. The concept of a mandala counteracts our natural tendency to look for the unified political power of later history, the power of large kingdoms and nation states, in earlier history where local power is more important. In the words of O. W. Wolters who originated the idea in 1982:

"The map of earlier Southeast Asia which evolved from the prehistoric networks of small settlements and reveals itself in historical records was a patchwork of often overlapping mandalas"[11]

In some ways similar to the feudal system of Europe, states were linked in overlord-tributary relationships. Compared to feudalism however, the system gave greater independence to the subordinate states; it emphasized personal rather than official or territorial relationships; and it was often non-exclusive. Any particular area, therefore, could be subject to several powers or none.

In Buddhism

Theravada Buddhism

The mandala can be found in the Atanatiya Sutta[12] in the Digha Nikaya, part of the Pali Canon. This text is frequently chanted.

Tibetan Vajrayana

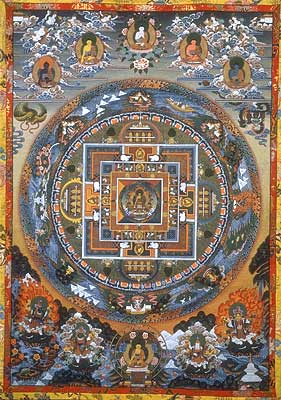

A kyil khor (Tibetan for mandala) in Vajrayana Buddhism usually depicts a landscape of the Buddha land or the enlightened vision of a Buddha (which are inevitably identified with and represent the nature of experience and the intricacies of both the enlightened and confused mind). Such mandalas consist of an outer circular mandala and an inner square (or sometimes circular) mandala with an ornately decorated mandala palace placed at the center. Any part of the inner mandala can be occupied by Buddhist glyphs and symbols[13] as well as images of its associated deities.

Mandalas are commonly used by tantric Buddhists as an aid to meditation. More specifically, a Buddhist mandala is envisaged as a "sacred space,"[14] a Pure Buddha Realm, and also as an abode of fully realized beings or deities. While on the one hand, it is regarded as a place separated and protected from the ever-changing and impure outer world of Samsara, [15] and is thus seen as a Buddhafield, or a place of Nirvana and peace, the view of Vajrayana Buddhism sees the greatest protection from samsara being the power to see samsaric confusion as the "shadow" of purity (which then points towards it). By visualizing purelands, one learns to understand experience itself as pure, and the abode of enlightenment. The protection we need, in this view, is from our own minds, as much as from external sources of confusion. In many tantric mandalas, this aspect of separation and protection from the outer samsaric world is depicted by "the four outer circles: the purifying fire of wisdom, the vajra circle, the circle with the eight tombs, the lotus circle."[13] The ring of vajras forms a connected fence-like arrangement running around the perimeter of the outer mandala circle.[13] The mandala is also "a support for the meditating person,"[13] something to be repeatedly contemplated, to the point of saturation, such that the image of the mandala becomes fully internalized in even the minutest detail and which can then be summoned and contemplated at will as a clear and vivid visualized image. With every mandala comes what Tucci calls "its associated liturgy… contained in texts known as tantras,"[16] instructing practitioners on how the mandala should be drawn, built and visualized and indicating the mantras to be recited during its ritual use. The various aspects of the traditionally fixed design represent symbolically the objects of worship and contemplation of the Tibetan Buddhist cosmology.

To symbolize impermanence (a central teaching of Buddhism), after days or weeks of creating the intricate pattern, the sand is brushed together and is usually placed in a body of running water to spread the blessings of the mandala.

The visualization and concretization of the mandala concept is one of the most significant contributions of Buddhism to Transpersonal Psychology. Mandalas are seen as sacred places which, by their very presence in the world, remind a viewer of the immanence of sanctity in the Universe and its potential in his or her self. In the context of the Buddhist path the purpose of a mandala is to put an end to human suffering, to attain enlightenment and to attain a correct view of Reality. It is a means to discover divinity by the realization that it resides within one's own self.

A mandala can also represent the entire Universe, which is traditionally depicted with Mount Meru as the Axis Mundi in the center, surrounded by the continents. A 'mandala offering'[17] in Tibetan Buddhism is a symbolic offering of the entire Universe. Every intricate detail of these mandalas is fixed in the tradition and has specific symbolic meanings, often on more than one level.

The mandala can be shown to represent in visual form the core essence of the Vajrayana teachings. In the mandala, the outer circle of fire usually symbolizes wisdom. The ring of 8 charnel grounds probably represent the Buddhist exhortation to always be mindful of death and impermanence with which samsara is suffused: "such locations were utilized in order to confront and to realize the transient nature of life."[18] Inside these rings lie the walls of the mandala palace itself, specifically a place populated by deities and Buddhas.

One well-known type of mandala in Japan is the mandala of the "Five Buddhas," archetypal Buddha forms embodying various aspects of enlightenment, the Buddhas are depicted depending on the school of Buddhism and even the specific purpose of the mandala. A common mandala of this type is that of the Five Wisdom Buddhas (a.k.a. Five Jinas), the Buddhas Vairocana, Aksobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha and Amoghasiddhi. When paired with another mandala depicting the Five Wisdom Kings, this forms the Mandala of the Two Realms.

Mandala offering

Whereas the above mandala represents the pure surroundings of a Buddha, this mandala represents the Universe. This type of mandala is used for the mandala-offerings, during which one symbolically offers the Universe to the Buddhas or one's teacher for example. Within Vajrayana practice, 100,000 of these mandala offerings (to create merit) can be part of the preliminary practices before a student can begin with actual tantric practices.[19] This mandala is generally structured according to the model of the Universe as taught in a Buddhist classic text the Abhidharmakosha, with Mount Meru at the center, surrounded by the continents, oceans, and mountains.

Shingon Buddhism

The Japanese branch of Vajrayana Buddhism, Shingon Buddhism, makes frequent use of mandalas in their rituals as well, though the actual mandalas differ. When Shingon's founder, Kukai returned from his training in China, he brought back two mandalas that became central to Shingon ritual: the Mandala of the Womb Realm and the Mandala of the Diamond Realm.

These two mandalas are engaged in the abhiseka initiation rituals for new Shingon students. A common feature in this ritual is to blindfold the new initiate and have them throw a flower upon either mandala. Where the flower lands assists in the determination of which tutelary deity the initiate should work with.

Sand Mandalas, as found in Tibetan Buddhism, are not practiced in Shingon Buddhism.

Nichiren Buddhism

The mandala in Nichiren Buddhism is called a moji-mandala (文字漫荼羅) and is a hanging paper scroll or wooden tablet whose inscription consists of Chinese characters and medieval-Sanskrit script representing elements of the Buddha's enlightenment, protective Buddhist deities and certain Buddhist concepts. Called the Gohonzon, it was originally inscribed by Nichiren, the founder of this branch of Japanese Buddhism, during the late thirteenth Century. The Gohonzon is the primary object of veneration in some Nichiren schools and the only one in others, which consider it to be the supreme object of worship as the embodiment of the supreme Dharma and Nichiren's inner enlightenment. The seven characters Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, considered to be the name of the supreme Dharma and the invocation that believers chant, are written down the center of all Nichiren-sect Gohonzons, whose appearance may otherwise vary depending on the particular school and other factors.

Pure Land Buddhism

Like Nichiren, Pure Land Buddhists such as Shinran and his descendent Rennyo sought a way to create objects of reverence, but objects that were readily available to the lower-classes of Japanese society that could not afford the traditional form of mandala. In the case of Shin Buddhism, Shinran designed a mandala using a hanging scroll, and the words of the nembutsu (南無阿彌陀佛) written vertically.

Such mandalas are still often used by Pure Land Buddhists in home altars (shrines) called butsudan today.

In Christianity

Painton Cowen, who dedicated his life to the study of rose windows,[20] states that mandala-esque forms are prevalent throughout Christianity: celtic cross; rosary; halo; aureole; oculi; Crown of Thorns; rose windows; Rosy Cross'; dromenon. [21] on the floor of Chartres Cathedral. The dromenon represents a journey from the outer world to the inner sacred center where the Divine is found.[22]

Similarly, many of the Illuminations of Hildegard von Bingen can be used as Mandalas, as are many of the images of esoteric Christianity (i.e., Christian Hermeticism, Christian Alchemy and Rosicrucianism).

In Islam

In Islam, sacred art is dominated by geometric shapes in which a segment of the circle, the crescent moon, together with a star, represent the Divine. The entire building of the mosque becomes a mandala as the interior dome of the roof represents the arch of the heavens and turns the worshiper's attention towards Allah.[23]

Medicine wheel as mandala

Medicine wheels are stone structures built by the natives of North America for various spiritual and ritual purposes. Medicine wheels were built by laying out stones in a circular pattern that often resembled a wagon wheel lying on its side. The wheels could be large, reaching diameters of 75 feet. Although archeologists are not definite on the intended purpose of each medicine wheel, it is considered that they had ceremonial and astronomical significance. Medicine wheels are still used today in the Native American spirituality, however most of the meaning behind them is not shared amongst non-Native peoples. Dream catchers are also mandalas.

Other Mandalas

Among Indigenous Australians, Bora is the name given both to an initiation ceremony, and to the site Bora Ring on which the initiation is performed. At such a site, young boys are transformed into men via rites of passage. The word Bora was originally from South-East Australia, but is now often used throughout Australia to describe an initiation site or ceremony. The term "bora" is held to be etymologically derived from that of the belt or girdle that encircles initiated men. The appearance of a Bora Ring varies from one culture to another, but it is often associated with stone arrangements, rock engravings, or other art works. Women are generally prohibited from entering a bora. In South East Australia, the Bora is often associated with the creator-spirit Baiame.

Bora rings, found in South-East Australia, are circles of foot-hardened earth surrounded by raised embankments. They were generally constructed in pairs (although some sites have three), with a bigger circle about 22 meters in diameter and a smaller one of about 14 meters. The rings are joined by a sacred walkway. Matthews gives an excellent eye-witness account of a Bora ceremony, and explains the use of the two circles.[24]

Notes

- ↑ David Fontana, Meditating with Mandalas: 52 New Mandalas to Help You Grow in Peace and Awareness (London: Duncan Baird Publishers, 2006, ISBN 1844831175), 10.

- ↑ Mandalas Crystal Links. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage, 1989, ISBN 0679723951), 186-197.

- ↑ Marty Chappell, Handout, how to make a mandala. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ Fontana, 12.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Vaman Shivram Apte, The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1965, ISBN 8120805674), 781.

- ↑ David Gordon White, The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996,ISBN 0226894991), 481, note 159.

- ↑ M. Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary (Nataraj Books, 2021, ISBN 978-1881338529), 845.

- ↑ Roderick Bucknell and Martin Stuart-Fox, The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism (London: Curzon Press, 1986, ISBN 0312825404), ix.

- ↑ Madhu Khanna, Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity (Inner Traditions, 2003, ISBN 0892811323), 21.

- ↑ O. W. Wolters, History, Culture and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1999, ISBN 0877277257), 27.

- ↑ Peter Skilling, Mahasutras: Great Discourses of the Buddha volume II, parts I & II (Wisdom Publications, 1994, ISBN 0860133192), 553ff.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Jytte Hansen, Mandala Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ The Mandala - Sacred Geometry and Art Article of the Month - September 2000 Mandala – Sacred Geometry in Buddhist Art Exotic India, September 2000. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ Vajra Karuna, Sudden or Gradual Enlightenment? Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ The Mandala in Tibet Asian Art. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ Alexander Berzin, What Is a Mandala? Study Buddhism. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ Of Charnel Grounds, Graveyards and Cremation Grounds Yoniverse. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ Venerable Thubten Chodron, Preliminary Practice (Ngondro) Thubten Chodron. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ↑ Painton Cowen, The Rose Window (Thames & Hudson, 2005, ISBN 978-0500511749).

- ↑ It is correctly termed a "dromenon," not a maze nor labyrinth, because there is only one path to the center.

- ↑ Fontana, 11, 54, 118.

- ↑ Fontana, 11-12.

- ↑ R.H. Matthews, The Burbung of the Darkinung Tribes , 1897, online [1] Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 10(1) (1897): 1-12. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Apte, Vaman Shivram. The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1965. ISBN 8120805674

- Bucknell, Roderick, and Martin Stuart-Fox. The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. London: Curzon Press, 1986. ISBN 0312825404

- Cowen, Painton. The Rose Window. Thames & Hudson, 2005. ISBN 978-0500511749

- Chandler, David. A History of Cambodia. Westview Press, 1983. ISBN 0813335116

- Fontana, David. Meditating with Mandalas: 52 New Mandalas to Help You Grow in Peace and Awareness. London: Duncan Baird Publishers, 2006. ISBN 1844831175

- Gold, Peter. Navajo and Tibetan Sacred Wisdom: The circle of the spirit. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International, 1994. ISBN 089281411X

- Jung, C.G., Clara Winston and Richard Winston (trans), Aniela Jaffe (ed.). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Vintage, 1989. ISBN 0679723951

- Khanna, Madhu. Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity. Inner Traditions, 2003. ISBN 0892811323

- Monier-Williams, M. A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Nataraj Books, 2021. ISBN 978-1881338529

- Skilling, Peter. Mahasutras: Great Discourses of the Buddha volume II, parts I & II. Wisdom Publications, 1994. ISBN 0860133192

- Thongchai Winichakul. Siam Mapped. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1984. ISBN 0824819748

- Tucci, Giuseppe. The Theory and Practice of the Mandala. Ixia Press, 2020. ISBN 978-0486842387

- White, David Gordon. The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0226894991

- Wolters, O.W. History, Culture and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1999. ISBN 0877277257

- Wyatt, David. Thailand: A Short History, 2nd ed. Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0300-084757

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.