Bison

| Bison | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

American bison | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||||

|

B. bison |

Bison are members of the genus Bison of the Bovid family of the even-toed ungulates, or hoofed mammals. There are two extant (living) species of living bison:

- The American bison (Bison bison bison), the most famous bison, formerly one of the most common large animals in North America

- The European bison or Wisent (Bison bonasus)

There were also several other species of bison which became extinct within the last 10,000 years.

Bison are often called "buffalo" in North America, but this is technically incorrect since true buffalo are native only to Asia (Water Buffalo) and Africa (see African Buffalo). Bison are very closely related to true buffalo, as well as cattle, yaks, and other members of the subfamily Bovinae, or bovines.

Bison physiology and behavior

[[Image:Wood-Buffalo-NP Waldbison 98-07-02.jpg|thumb|left|Wood bison, a sub-species of the American Bison] Bison are among the largest hoofed mammals, standing 1.5 to 2 meters (5 to 6.5 feet) at the shoulder and weighing 350 to 1000 kg (800 to 2,200 lbs). Males average larger than females. The head and forequarters are especially massive with a large hump on the shoulders. Both sexes have horns with the male's being somewhat larger (Nowak 1983).

Bison mature in about two years and have an average life span of about twenty years. A female bison can have a calf every year, with mating taking place in summer and birth in spring when conditions are best for the young animal. Bison are "polygynous": dominant bulls maintain a small harem of females for mating. Male bison fight with each other over the right to mate with females. The male bison's greater size, larger horns, and thicker covering of hair on the head and front of the body benefit them in these struggles. In many cases the smaller, younger, or less confident male will back down and no actual fight will take place (Lott 2002).

The bison's place in nature

Bison are strictly herbivores. American bison, which live mainly in grassslands, are grazers while European bison, living mainly in forests, are browsers. American bison migrate over the grassland to reach better conditions. In the past, herds of millions traveled hundreds of miles seasonally to take advantage of different growing conditions. This gives the grass a chance to recover and regrow. The bisons' droppings and urine fertilize the soil, returning needed nitrogen (Lott 2002).

Bison are subject to various parasites, among them the Winter tick, Dermacentor albipictus, a single one of which can reduce a calf's growth by 1.5 lbs (.7 kg) due to the blood it takes. Bison roll in dirt in order to remove ticks and other parasites. This also helps them to keep cool in hot weather (Lott 2002).

One animal that has a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship with the American bison is the Black-tailed prairie dog, Cynomys ludovicianus, a small rodent. Prairie dogs eat the same grass as the bison and live in large groups in underground tunnels called "towns." Bison are attracted to prairie dog towns by the large mounds of dirt removed from the tunnels, which the bison use to roll in. The bison benefit the prairie dogs by eating the tall grass and fertilizing the soil, both of which promote the growth of the more nutritious new short grass (Lott 2002).

Because of their large size and strength bison have few predators. In both America and Europe wolves, Canis lupus, are (or were) the most serious predator of bison (besides humans). The wolves' habit of hunting in groups enables them to prey on animals much larger than themselves. But most often it is the calves that fall victim to wolves. It has been suggested that the bison's tendency to run away from predators rather than standing and fighting like many other bovines, including probably the extinct bison species, has given them a better chance against wolves and later human hunters. The Brown bear (Ursus arctos), called the Grizzly bear in North America, also eats bison but is too slow to catch healthy, alert adult bison so mainly eats those that have died from cold or disease (Lott 2002).

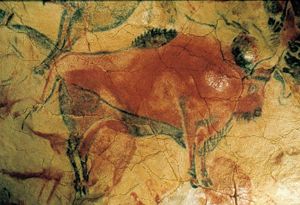

Bison and humans

Bison were an important prey for human hunters from prehistoric times. The National Bison Association lists over 150 traditional Native American uses for bison products, besides food (NBA 2006). After the introduction of the horse to North America in the 1500s made hunting bison easier, bison became even more important to some Native American tribes living on the Great Plains. It is estimated that there were about 30,000,000 bison in North America at this time (Lott 2002).

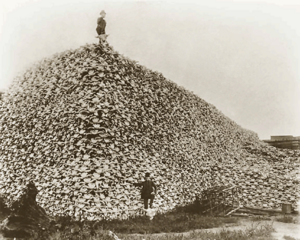

As white Americans moved into Native American lands, the bison were killed off. Some of the reasons for this were to free land for agriculture and cattle ranching, to sell the hides of the bison, as a tactic to deprive hostile tribes of their main food supply, and for what was considered sport. The worst of the killing took place in the 1870s and the early 1880s. By 1890, there were fewer than 1,000 bison in North America (Nowak 1983).

The European bison was also hunted almost to extinction by 1927 with the only survivors living in zoos. Since that time it has been reintroduced to the wild and there are about 3,000 living today.

The Wood bison, a subspecies of the American bison, had been reduced to about 250 animals by 1900 but has now recovered to about 9,000, living mainly in northwest Canada.

The American bison has also made a comeback with about 20,000 living in the wild in parks and preserves, including Yellowstone National Park, and about 500,000 living on ranches and tribal lands where they are managed although not domesticated. Bison ranching continues to expand yearly while bison meat becomes more popular, partly because of its lower fat and higher iron and vitamin B12 content compared to beef (NBA 2006).

For Americans the bison is an important part of history, a symbol of national identity, and a favorite subject of artists. Many American towns, sports teams, and other organizations use the bison as a symbol, most often under the name "Buffalo". For many Native Americans the bison holds an even greater importance. Fred DuBray of the Cheyenne River Sioux said (IBC 2006):

- "We recognize the bison is a symbol of our strength and unity, and that as we bring our herds back to health, we will also bring our people back to health."

[[Image:Soviet Union-1969-stamp-Wisent-10K.jpg|right|thumb|350px|European bison on a 1969 Soviet stamp]]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Intertribal Bison Cooperative (IBC). 2006. Website[1]

- Lott, D.F. 2002. American Bison. Berkeley, California : University of California Press

- National Bison Association (NBA). 2006 Website[2]

- Nowak, R.M. and Paradiso, J.L. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, Maryland : The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, New Jersey : Plexus Publishing, Inc.

Notes added from original version:

American Bison

The American Bison (Bison bison) is a bovine mammal that is the largest terrestrial mammal in North America, and one of the largest wild cattle in the world. With their huge bulk, wood bison – which are the largest subspecies in North America – are only surpassed in size by the massive Asian gaur and wild water buffalo, both of which are found mainly in India. Its two subspecies are the Plains Bison (Bison bison bison), distinguished by its smaller size and more rounded hump, and the Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae), distinguished by its larger size and taller square hump.

The Bison is also commonly known as the American Buffalo, although it is only distantly related to either the Water Buffalo or African Buffalo.

One very rare condition results in the white buffalo, where the calf turns entirely white. It is not to be confused with albino, since white bison still possess pigment in the skin, hair, and eyes. White bison are considered sacred by many Native Americans.

Buffalo trails

The first thoroughfares of North America, save for the time-obliterated paths of mastodon or musk-ox and the routes of the Mound Builders, were the traces made by bison and deer in seasonal migration and between feeding grounds and salt licks. Many of these routes, hammered by countless hoofs instinctively following watersheds and the crests of ridges in avoidance of lower places' summer muck and winter snowdrifts, were followed by the Indians as courses to hunting grounds and as warriors' paths; they were invaluable to explorers and were adopted by pioneers. Bison traces were characteristically north and south; there were, however, several key east-west trails which were used later as railways. Some of these include the Cumberland Gap; along the New York watershed; from the Potomac River through the Allegheny divide to the Ohio River headwaters; and through the Blue Ridge Mountains to upper Kentucky. In Senator Thomas Hart Benton's phrase saluting these sagacious pathmakers, the buffalo blazed the way for the railroads to the Pacific.

Source: James Truslow Adams, 1940. Dictionary of American History (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons)

===

Bison were hunted almost to extinction in the 19th century and were reduced to a few hundred head by the mid-1880s, from which all the present day's managed herds are descended. One major cause was that hunters were paid by large railroad concerns to destroy entire herds, for several reasons:

- The herds formed the basis of the economies of local Plains tribes of Native Americans; without bison, the tribes would leave.

- Herds of these large animals on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop in time.

- Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding though hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions. As a result, the herds could delay a train for days.

Bison skins were used for industrial machine belts, clothing such as robes, and rugs. There was a huge export trade to Europe of bison hides. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, cartridge reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and re-cast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters such as Buffalo Bill Cody killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their career. One professional hunter killed over 20,000 by his own count. A good hide could bring $3.00 in Dodge City, Kansas, and a very good one (the heavy winter coat) could sell for $50.00 in an era when a laborer would be lucky to make a dollar a day.

As the great herds began to wane, proposals to protect the bison were discussed. Cody, among others, spoke in favor of protecting the bison because he saw that the pressure on the species was too great. But these were discouraged since it was recognized that the Plains Indians, often at war with the United States, depended on bison for their way of life. General Phillip Sheridan spoke to the Texas Legislature against a proposal to outlaw commercial bison hunting for that reason, and President Grant also "pocket vetoed" a similar Federal bill to protect the dwindling bison herds. By 1884, the American Bison was close to extinction.

The Famous Buffalo Herd of James "Scotty" Philip in South Dakota was the beginning of the reintroduction of Bison to North America. In 1899, he purchased a small herd (5 of them, including the female) from Dug Carlin, Pete Dupree's brother-in-law, whose son Fred had roped 5 calves in the Last Big Buffalo Hunt on the Grand River in 1881 and taken them back home to the ranch on the Cheyenne River. At the time of purchase there were approximately 7 pure buffalo and it was believed to be one of the largest known herds left in North America. Scotty's goal was to preserve the animal from extinction. At the time of his death in 1911 at 53, Scotty had grown the herd to an estimated 1,000 to 1,200 head of Bison.

Hunting of wild bison is legal in some states and provinces where public herds require culling to maintain a target population. In Alberta, where one of only two continuously wild herds of bison exist in North America at Wood Buffalo National Park, bison are hunted to protect disease free herds of public (reintroduced) and private herds of bison. In Montana a public hunt was re-established in 2005, with 50 permits being issued. The Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Commission increased the number of tags to 140 for the 2006/2007 season. Advocacy groups claim that it is premature to re-establish the hunt, given the bison's lack of habitat and wildlife status in Montana.

One of the bison's few natural predators is the wolf. Wolves will usually prey on the females and young and rarely will go for healthy bulls. Bears will also prey on the young of bison.

American Bison today

Bison are now raised for meat and hides. Over 250,000 of the 350,000 remaining bison are being raised for human consumption. Bison meat is lower in fat and cholesterol than beef which has led to the development of beefalo, a fertile cross-breed of bison and domestic cattle. In 2005, about 35,000 bison were processed for meat in the U.S., with the National Bison Association and USDA providing a "Certified American Buffalo" program with birth-to-consumer tracking of bison via RFID ear tags.

Recent genetic studies of privately owned herds of bison show that many of them include animals with genes from domestic cattle; there are as few as 12,000 to 15,000 pure bison in the world. The numbers are uncertain because the tests so far used mitochondrial DNA analysis, and thus would miss cattle genes inherited in the male line; most of the hybrids look exactly like purebred bison.

The American Bison was depicted on the reverse side of the U.S. "buffalo nickel" from 1913 to 1938. In 2005, the United States Mint coined a nickel with a new depiction of the bison as part of its "Westward Journey" series; the Kansas and North Dakota quarters have a depiction of the bison on its reverse as part of its "50 State Quarter" series. The Kansas State Quarter only has the bison and does not feature any writing. The North Dakota State Quarter has two bison.

Wisent

The Wisent or European Bison (Bison bonasus) (IPA: [ˈviːzənt]) is a bison species and the heaviest land animal in Europe. A typical wisent is about 2.9 m long and 1.8–2 m tall, and weighs 300 to 1000 kg. It is typically lankier and less massive than the related American bison (B. bison), and has shorter hair on the neck, head, and forequarters. Wisents are forest-dwelling. Wisents were first scientifically described by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758. Some later descriptions treat the wisent as conspecific with the American bison. It is not to be confused with the aurochs.

The species is now endangered. In the past they were commonly killed to produce hides and drinking horns especially in the middle ages.

Near-extinction

In Western Europe, wisent were extinct by the 11th century except in the Ardennes, where they lasted into the 14th century. The last wisent in Transylvania died in 1790.

In the east, wisent were legally the property of the Polish kings, Lithuanian princes and Russian Tsars. King Sigismund the Old of Poland instituted the death penalty for poaching a wisent in the mid-1500s. Despite these and other measures, the wisent population continued to decline over the following four centuries. The last wild wisent in Poland was killed in 1919 and the last wild wisent in the world was killed by poachers 1927 in the Western Caucasus. By that year fewer than 50 remained, all in zoos.

Wisents were re-introduced successfully into the wild beginning in 1951. They are found living free-ranging in forest preserves like Western Caucasus in Russia and Białowieża Forest in Poland and Belarus. Free-ranging herds are found in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Russia and Kyrgyzstan. Zoos in 30 countries also have quite a few animals. There were 3000 individuals as of 2000, all descended from only 12 individuals. Because of their limited genetic pool, they are considered highly vulnerable to diseases like foot and mouth disease.

Wisents are now found in the 30km exclusion zone around Chernobyl. As with other animals, it seems that the benefits of removing people from the zone have far outweighed any harm from radiation. [1]

In 1996 the IUCN classified the wisent as endangered.

More details

Wisent have lived as long as 28 years in captivity although in the wild their lifespan is shorter. Productive breeding years are between 4 and 20 years old in females and only between 6 and 12 years old in males. Wisent occupy home ranges of as much as 100 square kilometers and some herds are found to prefer meadows and open areas in forests.

Wisent can cross-breed with American Bison. The products of a German interbreeding program were destroyed after World War II. This program was related to the impulse which created the Heck cattle. The cross-bred individuals created at other zoos were eliminated from breed books by the 1950s. A Russian back-breeding program resulted in a wild herd of hybrid animals which presently lives in the Caucasian Biosphere Reserve (550 individuals in 1999).

There are also bison-wisent-cattle hybrids. In 1847 a herd of wisent-cattle hybrids named żubroń was created by Leopold Walicki. The animal was to become a durable and cheap alternative to cattle. The experiment was continued by researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences until the late 1980s. Although the program resulted in a quite successful animal that was both hardy and could be bred in marginal grazing lands, it was eventually discontinued. Currently the only surviving żubroń herd consists of just a few animals in Białowieża Forest, Poland.

Three sub-species have been identified:

- Lowland wisent - Bison bonasus bonasus (Linneus, 1758) – (from Białowieża Forest)

- Hungarian (Carpathian) wisent - Bison bonasus hungarorum - extinct

- Caucasus wisent - Bison bonasus caucasicus - extinct, although one individual, a bull named Kaukasus was one of the 12 founders of the modern herds

The modern herds are managed as two separate lines - one consisting of only Bison bonasus bonasus (all descended from only 7 animals) and one consisting of all 12 ancestors including the one Bison bonasus caucasicus bull. Only a limited amount of inbreeding depression from the population bottleneck has been found, having a small effect on skeletal growth in cows and a small rise in calf mortality. Genetic variability continues to shrink. From 5 initial bulls, all current wisent bulls have one of only two remaining Y chromosomes.

Trivia

- The wisent (or Zubr in Slavic languages) is the largest wild animal in Belarus, and it is a national symbol of Belarus today.

- A wisent head (sometimes identified with an aurochs) featured on Moldavia's state symbols, a depiction connected with the legend of the country's foundation.

- Żubrówka Polish vodka is indirectly named after this animal (żubr in Polish). Each bottle contains a stalk of "bison grass", which produces a slighly yellowish colour and a distinctive flavour.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Wildlife defies Chernobyl radiation, by Stefen Mulvey, BBC News