Baal

Baal (baʿal) is a Semitic title meaning lord that is used for various deities, spirits, particularly of the Levant. In the Bible, "Baal" was a Canaanite god, the primary enemy of the Hebrew God Yahweh (who was also called "Lord.") A close reading of the Bible confirms the view that more than one deity was referred to as Baal. However, just as the concept of the Hebrew God grew and absorbed some of the characteristics of other lesser deities, Baal also seems to have been more than simply a local deity in time. He was a major deity in the Canaanite pantheon, being the son of the chief god El and his consort Ashera.

In some mythological texts Baal is used as a substitute for Hadad, just as "Lord" is used as a substitute for Yahweh. Hadad was the ruler of Heaven as well as a god of the sun, rain, thunder, fertility, and agriculture Since only priests were allowed to utter his divine name Hadad, Baal was used commonly. Many of the biblical references to Baal refer to a number of local spirit-deities worshipped as cult images, each called baals (Hebrew Baalim).

Deities called Ba’al and Ba’alath

Because more than one god bore the title "Ba’al" and more than one goddess bore the title "Ba’alat" or "Ba’alah," it is often difficult to be sure which Ba’al 'Lord' or Ba’alath 'Lady' a particular inscription or text is speaking of.

Though the god Hadad (or Adad) was especially likely to be called Ba’al, Hadad was far from the only god to have that title. The Ugaritic texts (mainly preserved in the Baal cycle) place the dwelling of Ba’al/Hadad on Mount Zephon, so one can probably take as evident that references to Ba’al Zephon in the Tanach and in inscriptions and tablets refer to Hadad. It is said that Ba’al Pe’or, the Lord of Mount Pe’or, whom Israelites were forbidden from worshipping (Numbers 1–25) was also Hadad. In the Canaanite pantheon, Hadad was the son of El, who had once been the primary god of the Canaanite pantheon, and whose name was also used interchangeably with that of the Hebrew god, Yahweh.

Melqart, the god of Tyre, was often called the Ba’al of Tyre. 1 Kings 16.31 relates that Ahab, king of Israel, married Jezebel, daughter of Ethba’al, king of the Sidonians, and then served habba’al ('the Ba’al'.) The cult of this god was prominent in Israel until the reign of Jehu, who put an end to it (2 Kings 10.26):

And they brought out the pillars (massebahs) of the house of the Ba’al and burned them. And they pulled down the pillar (massebah) of the Ba’al and pulled down the house of the Ba’al and turned it into a latrine until this day.

It is uncertain whether "the Ba’al" 'the Lord' refers to Melqart, to Hadad, who was also worshipped in Tyre, or Ba’al Shamîm 'Lord of Heaven' who was also worshipped in Tyre and often distinguished from Hadad. Josephus (Antiquities 8.13.1) states clearly that Jezebel "built a temple to the god of the Tyrians, which they call Belus" which certainly refers to Melqart. But Josephus may be relying on likelihood rather than knowledge. Hadad is generally a rain god but Melqart is not known to be connected with bringing of rain. But so little is known of Melqart's cult that such reasoning is not decisive.

In any case, King Ahab, despite supporting the cult of this Ba‘al, remained at the same time also a follower of Yahweh. Ahab still consulted Yahweh's prophets and cherished Yahweh's protection when he named his sons Ahaziah ("Yahweh holds") and Jehoram ("Yahweh is high.")

Ba'al of Carthage

The worship of Ba`al Hammon flourished in the Phoenician colony of Carthage. Ba'al Hammon was the supreme god of the Carthaginians and is generally identified by modern scholars either with the northwest Semitic god El or with Dagon, and generally identified by the Greeks with Cronus and by the Romans with Saturn.

The meaning of Hammon or Hamon is unclear. In the 19th century when Ernest Renan excavated the ruins of Hammon (Ḥammon), the modern Umm al-‘Awamid between Tyre and Acre, he found two Phoenician inscriptions dedicated to El-Hammon. Since El was normally identified with Cronus and Ba‘al Hammon was also identified with Cronus, it seemed possible they could be equated. More often a connection with Hebrew/Phoenician ḥammān 'brazier' has been proposed. Frank Moore Cross argued for a connection to Khamōn, the Ugaritic and Akkadian name for Mount Amanus, the great mountain separating Syria from Cilicia based on the occurrence of an Ugaritic description of El as the one of the Mountain Haman.

Classical sources relate how the Carthaginians burned their children as offerings to Ba’al Hammon. See Moloch for a discussion of these traditions and conflicting thoughts on the matter. Such a devouring of children fits well with the Greek traditions of Cronus.

Scholars tend to see Ba’al Hammon as more or less identical with the god El, who was also generally identified with Cronus and Saturn. However, Yigdal Ydin thought him to be a moon god. Edward Lipinski identifies him with the god Dagon in his Dictionnaire de la civilisation phenicienne et punique (1992: ISBN 2503500331). Inscriptions about Punic deities tend to be rather uninformative.

In Carthage and North Africa Ba’al Hammon was especially associated with the ram and was worshipped also as Ba’al Qarnaim ("Lord of Two Horns") in an open-air sancutary at Jebel Bu Kornein ("the two-horned hill") across the bay from Carthage.

Ba’al Hammon's female cult partner was Tanit. He was probably not ever identified with Ba’al Melqart, although one finds this equation in older scholarship.

Ba’alat Gebal ("Lady of Byblos") appears to have been generally identified with ‘Ashtart, although Sanchuniathon distinguishes the two.

Ba‘al as a divine title in Israel and Judah

- At first the name Baal was used by the Jews for their God without discrimination, but as the struggle between the two religions developed, the name Baal was given up in Judaism as a thing of shame, and even names like Jerubbaal were changed to Jerubbesheth: Hebrew bosheth means "shame". Zondervan's Pictorial Bible Dictionary (1976) ISBN 031023560X

Since Ba‘al simply means 'Lord', there is no obvious reason why it could not be applied to Yahweh as well as other gods. Perhaps it was. The judge Gideon was also called Jerubaal, a name which seems to mean 'Ba‘al strives' though Judges 6.32 makes the claim that the name was given to mock the god Ba‘al, whose shrine Gideon had destroyed, the intention being to imply: "Let Ba‘al strive as much as he can ... it will come to nothing."

After Gideon's death, according to Judges 8.33, the Israelites went astray and started to worship the Ba‘alîm (the Ba‘als) especially Ba‘al Berith ("Lord of the Covenant.") A few verses later (Judges 9.4) the story turns to all the citizens of Shechem — actually kol-ba‘alê šəkem another case of normal use of ba‘al not applied to a deity. These citizens of Shechem support Abimelech's attempt to become king by giving him 70 shekels from the House of Ba‘al Berith. It is hard to disassociate this Lord of the Covenant who is worshipped in Shechem from the covenant at Shechem described earlier in Joshua 24.25 in which the people agree to worship Yahweh. It is especially hard to do so when Judges 9.46 relates that all "the holders of the tower of Shechem" (kol-ba‘alê midgal-šəkem) enter bêt ’ēl bərît 'the House of El Berith', that is, 'the House of God of the Covenant'. Was Ba‘al then here just a title for El? Or did the covenant of Shechem perhaps originally not involve El at all but some other god who bore the title Ba‘al? Or were there different viewpoints about Yahweh, some seeing him as an aspect of Hadad, some as an aspect of El, some with other theories? Again, there is no clear answer.

One also finds Eshbaal (one of Saul's sons) and Beeliada (a son of David). The last name also appears as Eliada. This might show that at some period Ba‘al and El were used interchangeably even in the same name applied to the same person. More likely a later hand has cleaned up the text. Editors did play around with some names, sometimes substuting the form bosheth 'abomination' for ba‘al in names, whence the forms Ishbosheth instead of Eshbaal and Mephibosheth which is rendered Meribaal in 1 Chronicles 9.40. 1 Chronicles 12:5 mentions the name Bealiah (more accurately bə‘’alyâ) meaning "Yahweh is Ba‘al."

It is difficult to determinine to what extent the false worship which the prophets stigmatize is the worship of Yahweh under a conception and with rites which treated him as a local nature god or whether particular features of gods more often given the title Ba‘al were consciously recognized to be distinct from Yahwism from the first. Certainly some of the Ugaritic texts and Sanchuniathon report hostility between El and Hadad, perhaps representing a cultic and religious differences reflected in Hebrew tradition also, in which Yahweh in the Tanach is firmly identified with El and might be expected to be somewhat hostile to Ba’al/Hadad and the deities of his circle. But for Jeremiah and the Deuteronomist it also appears to be monotheism against polytheism (Jeremiah 11.12):

Then shall the cities of Judah and inhabitants of Jerusalem go and cry to the gods to whom they offer incense: but they shall not save them at all in the time of their trouble. For according to the number of your cities are your gods, O Judah; and according to the number of the streets of Jerusalem you have set up altars to the abominination, altars to burn incense to the Ba‘al.

Does this refer to other gods and one particular god, perhaps Hadad, who is especially "the Ba‘al"? Or does it refer to altars to burn incense to "the Ba‘al" to which each altar is raised, that is to as many different Ba‘al's as there were altars?

Multiple Ba‘als and ‘Ashtarts

One finds in the Tanach the plural forms bə‘ālîm 'Ba‘als' or 'Lords' and ‘aštārôt '‘Ashtarts', though such plurals do not appear in Phoenician or Canaanite or independent Aramaic sources.

One theory is that the folk of each territory or in each wandering clan worshipped their own Ba‘al, as the chief deity of each, the source of all the gifts of nature, the mysterious god of their fathers. As the god of fertility all the produce of the soil would be his, and his adherents would bring to him their tribute of first-fruits. He would be the patron of all growth and fertility, and, by the use of analogy characteristic of early thought, this Ba‘al would be the god of the productive element in its widest sense. Originating perhaps in the observation of the fertilizing effect of rains and streams upon the receptive and reproductive soil, Ba‘al worship became identical with nature-worship. Joined with the Ba‘als there would naturally be corresponding female figures which might be called ‘Ashtarts, embodiments of ‘Ashtart.

Through analogy and through the belief that one can control or aid the powers of nature by the practice of magic, particularly sympathetic magic, sexuality might characterize part of the cult of the Ba‘als and ‘Ashtarts. Post-Exilic allusions to the cult of Ba‘al Pe‘or suggest that orgies prevailed. On the summits of hills and mountains flourished the cult of the givers of increase, and "under every green tree" was practised the licentiousness which was held to secure abundance of crops. Human sacrifice, the burning of incense, violent and ecstatic exercises, ceremonial acts of bowing and kissing, the preparing of sacred mystic cakes (see also Asherah), appear among the offences denounced by the post-Exilic prophets; and show that the cult of Ba‘al (and ‘Ashtart) included characteristic features of worship which recur in various parts of the Semitic (and non-Semitic) world, although attached to other names. But it is also possible that such rites were performed to a local Ba‘al 'Lord' and a local ‘Ashtart without much concern as to whether or not they were the same as that of a nearby community or how they fitted into the national theology of Yahweh who had become a ruling high god of the heavens, increasingly disassociated from such things, at least in the minds of some worshippers.

Another theory is that the references to Ba‘als and ‘Ashtarts (and Asherahs) are to images or other standard symbols of these deities, that is statues and icons of Ba‘al Hadad, ‘Ashtart, and Asherah set up in various high places as well as those of other gods, the author listing the most prominent as types for all. The Deuteronomistic editor is as angered and saddened by worshipping of images as by worshipping other deities than Yahweh and wishes to emphasize the plurality of false deities as opposed to true worship of Yahweh at his single temple in Jerusalem as called for in the reforms of Josiah.

A reminiscence of Ba‘al as a title of a local fertility god (or referring to a particular god of subterraneous water) may occur in the Talmudic Hebrew phrases field of the ba‘al and place of the ba‘al and Arabic ba‘l used of land fertilised by subterraneous waters rather than by rain.

Common confusion over ba‘al

Because the word Baal is used as a common substitute for the sacred name Hadad, confusion often arises when the same word is used for other deities, physical representations of gods and even people.

Historically, this confusion was resolved the nineteenth century as new archaeological evidence indicated multiple gods bearing the title Ba‘al and little about them that connected them to the sun. In 1899, the Encyclopædia Biblica article Baal by W. Robertson Smith and George F. Moore states:

That Baal was primarily a sun-god was for a long time almost a dogma among scholars and is still often repeated. This doctrine is connected with theories of the origin of religion which are now almost universally abandoned. The worship of the heavenly bodies is not the beginning of religion. Moreover, there was not, as this theory assumes, one god Baal, worshipped under different forms and names by the Semitic peoples, but a multitude of local Baals, each the inhabitant of his own place, the protector and benefactor of those who worshipped him there. Even in the astro-theology of the Babylonians the star of Bēl was not the sun : it was the planet Jupiter. There is no intimation in the OT that any of the Canaanite Baals were sun-gods, or that the worship of the sun (Shemesh), of which we have ample evidence, both early and late, was connected with that of the Baals ; in 2 K. 235 cp 11 the cults are treated as distinct.

The demon entitled ba'al

Other spellings: Bael, Baël (French), Baell.

Baal is also seen as a Christian demon. This is a potential source of confusion.

Until archaeological digs at Ras Shamra and Ebla uncovered texts explaining the Syrian pantheon, the demon Ba‘al Zebûb was frequently confused with various Semitic spirits and deities entitled ba‘al, and in some Christian writings it might refer to a high-ranking devil or to Satan himself.

In the ancient world of the Persian Empire, from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, worship of inanimate idols of wood and metal was being rejected in favor of "the one living God." In the Levant the idols were called "baals", each of which represented a local spirit-deity or "demon." Worship of all such spirits was rejected as immoral, and many were in fact considered malevolent and dangerous.

Early demonologists, unaware of Hadad or that "Baal" in the Bible referred to any number of local spirits, came to regard the term as referring to but one personage. Baal (usually spelt "Bael" in this context; there is a possibility that the two figures aren't connected) was ranked as the first and principal king in Hell, ruling over the East. According to some authors Baal is a duke, with 66 legions of demons under his command.

During the English Puritan period, Baal was either compared to Satan or considered his main lieutenant. According to Francis Barrett, he has the power to make those who invoke him invisible, and to some other demonologists his power is stronger in October. According to some sources, he can make people wise, and speaks hoarsely.

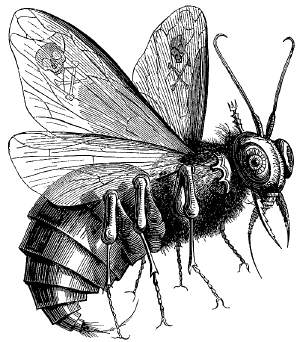

While the Semitic high god Baal Hadad was depicted as a human, ram or a bull, the demon Bael was in grimoire tradition said to appear in the forms of a man, cat, toad, or combinations thereof. An illustration in Collin de Plancy's 1818 book Dictionnaire Infernal rather curiously placed the heads of the three creatures onto a set of spider legs.

Ba'al Zebûb

Another version of the demon Ba'al is Beelzebub, or more accurately Ba‘al Zebûb or Ba‘al Zəbûb (Hebrew בעל זבוב, Ba'al zvuv), who was originally the name of a deity worshipped in the Philistine city of Ekron. Ba‘al Zebûb might mean 'Lord of Zebûb', referring to an unknown place named Zebûb, a pun with 'Lord of flies', zebûb being a Hebrew collective noun meaning 'fly'. This may mean that the Hebrews were derogating the god of their enemy. Later, Christian writings referred to Ba‘al Zebûb as a demon or devil, often interchanged with Beelzebul. Either form may appear as an alternate name for Satan (or the Devil) or may appear to refer to the name of a lesser devil. As with several religions, the names of any earlier foreign or "pagan" deities often became synonymous with the concept of an adversarial entity. The demonization of Ba‘al Zebûb led to much of the modern religious personification of Satan as the adversary of the Abrahamic god.

Some scholars have suggested that Baal Zebul which means "lord the prince" was deliberately changed by the worshippers of Yahweh to Baal Zebub (lord of the flies) in order to ridicule and protest the worship of Baal Zebul. (NIV Study Bible published by Zondervan)

Non-religious usage of ba'al

Baʿal (Bet-Ayin-Lamed; בַּעַל / בָּעַל, Standard Hebrew Báʿal, Tiberian Hebrew Báʿal / Báʿal) is a northwest Semitic word signifying 'The Lord, master, owner (male), husband' cognate with Akkadian Bēl of the same meanings. The feminine form is Phoenician בעלת Baʿalat, Hebrew בַּעֲלָה Baʿalāh signifying 'lady, mistress, owner (female), wife'.

The words themselves had no exclusively religious connotation, just as "father" or "lord" are used in religious meaning today—but they were not used in reference between a superior and an inferior or of a master to a slave. The words were used as titles in reference to one or various gods and goddesses, either in declaration of the deity as the Lord or Lady of a particular place (or rite), or standing alone as a term of reverence.

From the Tanach: Genesis 14.13 ba‘alê bərît-’abrām 'lords of the covenant of Abram', i.e. 'holders of an agreement with Abram', i.e. 'confederates of Abram' or 'allies of Abram'; Genesis 20.3: bə‘ulat bā‘al 'lady of a lord', i.e. 'wife of a man'; Genesis 37.19: ba‘al haḥalōmôt 'lord of the dreams', i.e. 'the one who made himself important in his dreams' or simply 'the dreamer'; Exodus 21.3: ba‘al ’iššâ 'lord of a woman', i.e. 'married man'; Exodus 21.22: ba‘al hā’iššâ 'lord of the woman', i.e. 'husband of the woman'; Exodus 24.14: mî-ba‘al dəbārîm 'who (is) lord of matters', i.e. 'whoever possesses some matter', i.e. 'whoever has a problem'; Leviticus 21.4: ba‘al bə‘ēmmāyw 'lord in his people', i.e. 'man of importance among his people'; Deuteronomy 24.4: ba‘lāh hāri’šôn 'her lord the former', i.e. 'her former husband'; and so forth. But these should suffice to show the range of the words.

In medieval Judaism, a rabbi who appeared to have supernatural powers was called a Ba‘al Shem 'Master of the Name' with no perception of any connection with Ba‘al as a title for a pagan god. Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (1678–1760) who founded the Hassidic movement, was commonly known during his later life as Ba‘al Shem Tov ("Good Master of the Name") and is still commonly called by that title today.

In Wales, there are many Hebrew place names left over from a religious revival that happened a few centuries ago. One of these places is a village called Bryn-y-baal between Buckley and Mold in Flintshire in Wales.

In popular culture

- Baal is the title of Bertolt Brecht 's first full-length play.

- "Ba'alzamon" is also a character in Robert Jordan's Wheel of Time series.

- Baal is the name of one of the three Prime Evils in the computer game Diablo II.

- In Warhammer 40,000, the Blood Angels Space marine legion is from a planet called Baal.

- "Ba'al" (pronounced similarly as 'ball') is a major Goa'uld System Lord and the main protagonist in Season 8 of Stargate SG-1.

Baal is also the name of the most powerful enemy in most Nippon Ichi games. Every time he is defeated, he gets a new body, but he occasionally gets his original body back.

- One of the Jenolan Caves in New South Wales, Australia is called "The Temple of Baal."

See also

- Hadad

- Canaanite religion

- Baal Peor

- Ba‘al Shamîm

- Beelzebub

- Bel

- Melqart

- Moloch

- The Lesser Key of Solomon

- Ars Goetia

- Baal (Stargate) - A fictional Alien who impersonates Baal

External links

- Article Baal, Baalim from The Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Article Baal by W. Robertson Smith and George F. Moore in Encyclopædia Biblica, edited T. K. Cheyne and J. Sutherland Black, MacMillan: London, 1899) (PDF format. Still quite accurate.)

- Bartleby: American Heritage Dictionary: Semitic roots: bcl.

- Scarce Punic images of Baal Hammon described.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.