Difference between revisions of "Anti-communism" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (105 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

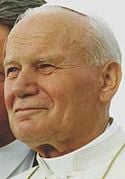

| − | '''Anti-communism''' refers to opposition to [[communism]], especially [[Marxism- | + | [[Image:Pope-poland.jpg|thumb|350px|Pope John Paul II speaks to crowds in Poland in 1979]] |

| + | '''Anti-communism''' refers to opposition to [[communism]], especially [[Marxism-Leninism]]. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the growing power of the communist movement after the [[Soviet Union]] was established in 1917. | ||

| − | + | [[monarchism|Monarchists]], Christians, [[Liberalism|classical Liberals]], [[Social Democracy|social-democrats]], and pro-[[free market]] forces in [[Europe]] opposed the first wave of [[communist revolution]]s from 1917 to 1922. [[Fascism]] and [[Nazism]] were based in part on a violent form of anti-communism. After [[World War II]], the liberal democracies took the lead in opposing Soviet communism during the [[Cold War]]. The [[human rights]] movement of the late twentieth century added a strong moral component to the anti-communist cause, exposing gross abuses of human rights in the communist world. At the same time, military dictatorships sometimes used anti-communism as a justification for harsh repression of political opposition. | |

| − | + | The country best known for being an opponent of communism is the [[United States]], together with its long-time allies like the [[United Kingdom]], [[Canada]], [[France]], and [[Australia]]. In addition to government policies to resist the spread of Soviet communism, anti-communist [[NGO's|non-governmental organizations]] in these countries did much to heighten the world's awareness of communism. | |

| − | + | The 1991 [[collapse of the Soviet Union]] was a major victory for the anti-communist cause, which generally viewed the [[Soviet Union|USSR]] as the heart of the communist threat. Anti-communism today often focuses on exposing human rights abuses in the remaining [[Marxism-Leninism|Marxist-Leninist]] regimes and preventing extreme left-wing movements from taking over democratic nations. | |

| − | + | ==The career of anti-communism== | |

| − | + | {{communism}} | |

| − | + | In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the [[communism|communist]] movement was at odds with the traditional monarchies that ruled over much of the [[Europe]]an continent. At the time, monarchists and religious leaders who supported traditional [[monarchy|monarchies]] were the most prominent anti-communists, and many European monarchies outlawed the public expression of communist views. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | However, after [[World War I]], several European monarchies were overthrown in a series of revolutions and military engagements. The most conservative European monarchy, the Russian empire, was replaced by the communist-run [[Soviet Union]]. The [[Russian Revolution]] also inspired and actively supported a series of other communist revolutions across Europe in the years of 1917-1922. The Soviet policy of ruthlessly repressing the new regime's opponents and treating religious leaders as enemies of the state, meanwhile, shocked much of the world. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Franco eisenhower 1959 madrid.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Francisco Franco and President [[Dwight D. Eisenhower]] in Madrid in 1959.]] | |

| − | + | The 1920s and 1930s saw the fading of traditionalist [[conservatism]]. The mantle of anti-communism was thus taken up by [[United States|American]]-inspired [[Liberalism]] on the one hand and the rising [[fascism|fascist]] movements on the other. These became the "two faces" of anti-communism over the next several decades. | |

| − | + | Since communism remained largely a European phenomenon, American anti-communist sentiments tended to follow their European counterparts. When communist groups and political parties began appearing elsewhere in the world, such as [[China]] in the late 1920s, their first opponents were usually either [[colonialism|colonial authorities]] or local nationalist movements, often inspired by American [[democracy]], but sometimes by fascism. Anti-communist [[dictatorship]]s that were established in Europe in the late 1930s, such as the government of [[Francisco Franco]] in [[Spain]], are considered to fall somewhere on the border between traditional [[conservatism]] and [[fascism]]. | |

| − | + | During [[World War II]], the liberal democracies set aside anti-communism in order to ally themselves with [[Stalin]]'s Russia against [[Hitler]]and Nazi Germany, and non-governmental organizations opposed to communism suffered a setback. After World War II, the [[Soviet Union]] became a superpower, and communism became a truly global phenomenon back by substantial military might, with a commitment to fomenting revolution throughout the capitalist world. This threat made anti-communism an integral part of the domestic and foreign policies of the [[United States]] and its [[NATO]] allies. | |

| − | + | [[Winston Churchill]] warned the world that a communist "Iron Curtain" had fallen in Eastern Europe, while the United States considered anti-communism the top priority of its foreign policy. As the reality of Stalin's tyranny became more apparent, liberal anti-communism gained increasing moral authority. Meanwhile, conservatism in the post-war era abandoned its monarchist and aristocratic associations, focusing instead on the preservation of the [[free market]], [[private property]], [[human rights]], the legitimate interests of large [[corporation]]s, and the defense of traditional moral and religious values. This attitude became a cornerstone of American conservative thought in the 1940s and 1950s. The rise of [[Communist China]] raised the specter of communism taking over Asia, and the effort of the Soviet Union and China to foster revolution throughout the developing world made the communist threat a very real one in many people's minds. | |

| − | + | The United States and its allies in the [[United Nations]] joined to oppose communist aggression during the [[Korean War]], when the Stalinist North Korean regime of [[Kim Il-sung]] invaded the South in an attempt to unify the country under communist rule. During this time, American conservatives sought to combat what they saw as a growing communist influence at home. This led to the adoption of a number of repressive domestic policies that are collectively known under the term "[[McCarthyism]]." | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the 1960s, the United States attempted once again to stop the communist advance, this time in [[Vietnam]]. Unlike in [[Korea]], where the north was the clear aggressor and the United States effort was highly popular among South Koreans, American forces in Vietnam found themselves mired in a less clear-cut situation. The United States ultimately withdrew from the conflict and allowed the communists to take over not only Vietnam, but [[Cambodia]] and [[Laos]] as well, resulting in terrible human losses, especially in Cambodia's "[[killing fields]]." | |

| − | + | Throughout the [[Cold War]], governments in [[Asia]], [[Africa]], and [[Latin America]] turned to the United States for political and economic support. Some of these were liberal democracies, but others were [[authoritarian]] regimes, which—according to their critics—used the fear of communism as a means of legitimizing repression. | |

| − | + | During the 1970s, communist-led revolutions in South America, Africa, and Asia advanced in the wake of the United States failure in Vietnam. The United States often found itself supporting or tolerating repressive, sometimes [[racism|racist]], regimes who resisted Soviet—and Chinese—led insurgencies. The moral ambiguity of this situation often placed democratic anti-communists on the ethical defensive. On the other hand, dissidents in the Soviet Union added their voices to the anti-communist cause by exposing abuses of human rights such as the [[Gulag Archipelago]]. In the 1980s, the conservative governments of [[Ronald Reagan]] in the United States and [[Margaret Thatcher]] in [[Great Britain]] followed a strongly anti-Soviet foreign policy that is credited as a major factor in the fall of the Soviet Union and the democratization of [[Eastern Europe]] and other countries. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the aftermath of the [[Cold War]], communism is no longer seen as a major force in world politics. However, both liberals and conservatives express concerns over human rights abuses in [[China]], [[Cuba]], and [[North Korea]]; and anti-communist groups continue to struggle against resurgent far-[[leftism]] in such nations as [[Nicaragua]] and [[Venezuela]]. | |

| − | + | ==Special types of anti-communism== | |

| + | ===Religious anti-communism=== | ||

| + | [[File:Dalai Lama 1430 Luca Galuzzi 2007crop.jpg|thumb|left|180px|The Fourteenth Dalai Lama, who was ousted from Tibet by Communist Chinese forces.]] | ||

| + | Soviet communism followed [[Karl Marx]] in teaching that religion was the "opiate of the masses" and thus actively sought to destroy religious institutions. The main target of communist "militant [[atheism]]" in the Soviet Union was usually the [[Russian Orthodox Church]], but [[Catholic]]s, [[Jew]]s, [[Muslim]]s, and [[Buddhism|Buddhists]] were also were persecuted. Thousands of priests and believers died when they resisted communist attempts to turn churches into "museums of atheism." The communists also murdered priests deemed ideologically hostile to [[socialism]], especially those known to have been loyal to the [[tsar]]. A similar pattern emerged in [[China]], [[Tibet]], [[North Korea]], [[North Vietnam]], [[Mongolia]] and other communist strongholds, with Buddhists, Christians of various denominations, and others feeling the brunt of communist repression. | ||

| − | + | The Orthodox churches sometimes resisted the communists, but Orthodox leaders also were willing to compromise with the Soviet state, even to the degree of being suspected of working with the secret police to root out believers who were disloyal to Soviet policy. The relatively cooperative attitude of the [[Russian Orthodox Church]] resulted both from a desire to retain at least a few of its believers and protect its most sacred sites, and also from a long-standing attitude in the Orthodox tradition which held that the church and state should work in [[harmonia|harmony]] with one another wherever possible. Nevertheless, Orthodox believers often spoke out against communism, and in the west many Orthodox Christians were active in anti-communist movements. | |

| − | + | [[Image:JohannesPaulII.jpg|thumb|125px|Pope John Paul II]] | |

| + | The Catholic Church, on the other hand, has a strong and official history of anti-communism dating back to well before the days of the Russian Revolution. In 1864, [[Pope Pius IX]] issued a [[pope|Papal]] [[encyclical]] called ''[[Quanta Cura]]'' in which he called communism and socialism a "most fatal error." [http://www.papalencyclicals.net/Pius09/p9quanta.htm] ''PapalEncyclicals''. Retrieved September 6, 2008. One factor in the later difference between the Catholic and Orthodox attitudes is that Catholicism's headquarters lay outside the Soviet Empire, in Rome. Additionally, from ancient times, the papacy had consistently confronted secular rulers it considered incompatible with the Catholic faith. In [[Hungary]], Cardinal [[Josef Mindszenty]] became an international symbol of opposition to communist religious oppression, and Catholic leaders in other communist nations often rankled communist authorities. The best known of these today was the Polish cardinal Karol Wojtyła, who later became [[Pope John Paul II]]. | ||

| − | + | Protestants were often even more vocal in their opposition to communism. Without strong international backing, as compared to the Catholics, however, they lacked political leverage and were repressed by the communists in the most brutal manner. In the United States, groups such as the [[Christian Anti-Communism Crusade]] and the [[Voice of the Martyrs]] rose to alert Christians to the suffering of their fellow believers in the communist world. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In [[Tibet]], the [[Dalai Lama]] became a symbol of communist repression of religion in Asia when the Chinese communist invaded Tibet and forced him into exile. Other Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and indigenous religious groups, though less known, face similar oppression. | |

| − | + | Jews, too, faced repression in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Orthodox Jews faced serious persecution not unlike that of the Christians, while secular Jews faced job discrimination, and all Jews found it virtually impossible to leave the country. Jewish anti-communism in the West usually found expression in broader political movements such as social democracy and labor unions, but in the 1970s a large-scale campaign on behalf of Soviet Jewry found expression in Jewish [[synagogues]]. Jews were also in the forefront of the [[neo-conservatism|neo-conservative]] movement that became a prominent factor developing the Reagan administration's anti-communist foreign policy. | |

| − | + | ===Fascist anti-communism=== | |

| + | [[Fascism]] and Soviet Communism both arose to prominence after [[World War I]]. At the end of the war, socialist uprisings, or the threat of them, arose throughout Europe. In Germany, the [[Spartacist uprising]] of January 1919 failed, but in Bavaria, communists successfully overthrew the government and established the [[Bavarian Soviet Republic]], which lasted for a few weeks in 1919. Similar short-lived Soviet republics emerged in other German states and a Soviet government was also briefly established in [[Hungary]] under [[Béla Kun]] in 1919. The Russian Revolution also inspired revolutionary movements in [[Italy]], a wave of labor strikes in Britain, the [[Winnipeg General Strike]] in Canada, the [[Seattle General Strike of 1919|Seattle General Strike]] in the United States, and other radical events. | ||

| − | + | [[File:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-B23938, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini.jpg|thumb|250px|Mussolini and Hitler]] | |

| + | Fascism was in part a reaction against these developments. Italian fascism, led by [[Benito Mussolini]], took power in 1922 with the blessing of Italy's king after years of leftist unrest led many conservatives to fear that a communist revolution was a very real threat. Throughout Europe, numerous [[aristocracy|aristocrats]] and [[Conservatism|conservative]] intellectuals, as well as [[capitalism|capitalists]] and [[industrialism|industrialists]], lent their support to fascist movements that arose in emulation of Italian fascism. Meanwhile, in [[Germany]], numerous extreme right-wing nationalist groups arose, based in part on the threat of communism. | ||

| − | + | During the worldwide [[Great Depression]] of the 1930s, communist and fascist movements were bitterly and often violently opposed to each other. The most notable example of this conflict was the [[Spanish Civil War]], which became in part a [[proxy war]] between the fascists and conservatives who backed [[Francisco Franco]] and the pro-Soviet communist movements (allied uneasily with [[Anarchism|anarchists]] and [[Trotskyism|Trotskyists]]) which backed the [[Second Spanish Republic|Republican]] government and were aided materially by the [[Soviet Union]]. | |

| − | + | [[Adolf Hitler]], too, rose to power partly on the basis of his anti-communism, as well as his [[ideology]] of [[Aryanism|Aryan]] superiority and [[anti-Semitism]]. Indeed, much of Hitler's anti-Semitism focused on the alleged [[Jew]]ish responsibility for the rise of communism. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Initially, the [[Soviet Union]] supported a coalition with the Western powers against [[Nazi Germany]], as well as [[popular front]]s in various countries against domestic fascism. The [[Munich Agreement]] between Germany, France, and Britain heightened Soviet fears that the Western powers were endeavoring to force them to bear the brunt of a war against Nazism. The Soviets thus negotiated a non-aggression pact with Germany—the [[Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact]] in 1939, more commonly known as the [[Hitler-Stalin Pact]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Stalin was taken by surprise when [[Nazi Germany]] broke the pact and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 in [[Operation Barbarossa]]. Fascism and communism reverted to their relationship as lethal enemies, with the war—in the eyes of both sides—becoming one between their respective ideologies. | |

| − | + | With the defeat of the [[Axis Powers]], fascist anti-communism was dealt a death blow. However, fascist elements persisted in the world anti-communist movement, often to the dismay of its other components. | |

| − | + | ==United States Anti-communism and the Cold War== | |

| + | Following [[World War II]] and the rise of the [[Soviet Union]] as a major world power, the objections to communism took on an added urgency. Many worried about the human rights of the millions of people who had recently come under communist rule in the wake of [[Stalin]]'s policies. The fear of many anti-communists in the United States was that communism would eventually become a direct threat to the government of the United States. This view led to the so-called "domino theory," in which a communist takeover in certain nations could not be tolerated, because it could lead to a chain reaction which would result in a triumph of world communism. There were also fears, not unfounded, that powerful nations like the Soviet Union and the [[People's Republic of China]] were using their power to create and support anti-democratic revolutions, as well as to forcibly assimilate formerly free nations into communist rule. The United States policy of halting further communist expansion, first enunciated by President [[Harry S. Truman]], came to be known as "[[containment]]." | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Crane removed part of Wall Brandenburg Gate.jpg|thumb|250px|A crane demolishes part of the [[Berlin Wall]] in 1989.]] | |

| + | The United States government thus based its anti-communism both on national defense priorities and the human rights record of Communist states. These states killed millions of their own people in the course of ending [[capitalism]] and continued to suppress civil liberties of the surviving population. | ||

| − | + | The policy succeeded in stemming the communist advance in [[Korea]] in the early 1950s, but Cuba was lost to communism in 1959. Then, after the United States debacle in Vietnam, anti-communists despaired that their cause could prevail. However, during the presidency of [[Ronald Reagan]], himself an ardent anti-communist of long standing, a surprising change took place. Calling the Soviet Union an "evil empire" and pursuing a policy of funding United States military superiority, Reagan pressured the Soviets to compete, to the point that their bankrupt economy began to collapse. Soon, the [[Berlin Wall]] had been torn down, the "Iron Curtain" began to rise, and the Soviet Union itself was no more. | |

| − | Anti- | + | ===Anti-communism and NGOs=== |

| + | A number of U.S. groups and publications worked to oppose communism during the [[Cold War]]. These include, in alphabetical order: | ||

| + | *'''[[Accuracy In Media]]''': One of America's first media watchdog groups, A.I.M. focused especially on the mainstream media's lack of balance in reporting on anti-communist issues. | ||

| + | *'''[[AFL-CIO]]''': America's largest labor federation was a bastion of anti-communism during the [[Vietnam]] era under its hard-nosed leader [[George Meany]], whose invitation to [[Alexandre Solzhenitsyn]] to speak at AFL-CIO meetings brought awareness of Soviet human rights abuses to U.S. audiences. | ||

| + | [[Image:1981 US Cabinet.jpg|thumb|300px|The Committee on the Present Danger provided several members of the Reagan Cabinet, including Jeane Kirkpatrick (center) and William Casey (far right).]] | ||

| + | *'''[[American Security Council]]''': An anti-communist group in Washington that concentrated on the military dimension of the [[Cold War]]. | ||

| + | *'''[[Captive Nations Committee]]''': A coalition of anti-communists which sponsored the annual Captive Nations Week, led for many years by Dr. [[Lev Dobriansky]]. | ||

| + | *'''[[Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation]]''': A [[Catholic]]-based educational organization named after the famous Hungarian prelate who was persecuted in his home country and found sanctuary for several years in the United States Embassy. | ||

| + | *'''[[CAUSA International]]''': The [[Unificationist]] successor to the Freedom Leadership Foundation, which created sophisticated anti-communist seminars during the 1980s, both in the United States and Latin America. | ||

| + | *'''[[Christian Anti-Communism Crusade]]''': A U.S. educational organization led by Dr. [[Fred Schwarz]], which engaged in large scale seminars focusing on communism's incompatibility with Christianity. | ||

| + | *'''''[[Commentary]]'' Magazine''': Founded by the [[American Jewish Committee]] in 1945, ''Commentary'' was a leading voice for liberal anti-communism and later became the principal organ of [[neo-conservatism]]. | ||

| + | *'''[[Committee on the Present Danger]]''': Originally formed in the 1950s, the CPD was revived in 1972, involving a number of hard-line democrats as well as Republicans. It became a major influence on several U.S. administrations especially that of [[Ronald Reagan]]. | ||

| + | *'''[[Council Against Communist Aggression]]''': A Washington D.C.-based group created to foster communication and networking among anti-communist groups and individuals in the nation's capital. | ||

| + | *'''Cuban Anti-Communist Groups''': Various [[Cuba]]n anti-communist movements ranged from groups such as Alpha 66 (a militant group accused of acts of violence and arson) to the more moderate [[Cuban American National Foundation]]. | ||

| + | *'''[[Freedom House]]''': The oldest human rights group in the United States provided factual evidence and a ratings system that exposed communist countries as the greatest violators of freedom. | ||

| + | *'''[[Freedom Leadership Foundation]]''': A Unificationist educational organization that promoted the cause of Soviet dissidents, confronted leftist groups on campus, and educated young people against [[Marxism|Marxist]] ideology. | ||

| + | *'''[[Heritage Foundation]]''': The leading conservative "think tank" in Washington, D.C. | ||

| + | *'''[[Human Events]]''': A Washington-based conservative weekly tabloid newspaper and later a magazine. | ||

| + | *'''[[Hungarian Freedom Fighters]] Federation''': An association of pro-democracy [[Hungary|Hungarians]] who had supported their nation's unsuccessful resistance to communist aggression in 1956. | ||

| + | *'''[[National Alliance of Russian Solidarists]]''': A Russian organization known by the acronym "NTS" and founded in 1930 by a group of young Russian anticommunists, led in the US by [[Constantin W. Boldyreff]]. | ||

| + | *'''[[National Committee for a Free Europe]]''': Founded in 1949 in New York and dedicated to opposing [[Stalin]]'s Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe, this group's main contribution was the founding of the government-supported broadcaster [[Radio Free Europe]]. | ||

| + | *'''''[[National Review]]''': A leading conservative magazine founded in New York by [[William F. Buckley, Jr.]] in 1955. | ||

| + | *'''''[[The New Republic]]''''': A venerable liberal magazine which, though opposed to the Vietnam War, was strongly critical of both the [[Soviet Union]] and the [[New Left]]. | ||

| + | *'''[[Voice of the Martyrs]]''': Founded by the persecuted Romanian pastor [[Richard Wurmbrandt]] and dedicated to publicizing the plight of Protestants and other Christians in Eastern Europe. | ||

| + | *'''[[U.S. Council for World Freedom]]''': Created in the early 1970s to act as the United States coordinating committee to send delegations to the [[World Anti-Communist League]] meetings. | ||

| + | *'''''[[The Washington Times]]''''' A daily newspaper in Washington D.C., and later with a national weekly, founded by the Reverend [[Sun Myung Moon]] to balance the liberal influence of the ''[[Washington Post]].'' | ||

| + | *'''[[Young Americans for Freedom]]''': A group of young conservatives inspired by the presidential candidacy of [[Barry Goldwater]] which also engaged in debates and demonstrations on college campuses against communism. | ||

| + | *'''[[Young People's Social League]]''': The youth arm of the Social Democrats USA, which had split with the United States Socialist Party over Vietnam. YPSL battled other socialist groups on campuses and provided a number of intellectual leaders known later as "neocons." | ||

| − | === | + | ===After the Cold War=== |

| − | + | Anti-communism became significantly muted after the fall of the Soviet Union and the [[Eastern bloc]] communist regimes in Eastern and Central Europe between 1989 and 1991. The fear of a worldwide communist takeover is no longer a serious concern. Remnants of anti-communism remain, however, in United States foreign policy toward [[Cuba]], [[People's Republic of China|mainland China]], and [[North Korea]]. The growth of China as a major economic and military power is a major concern for some. The [[Conservatism|conservative]] wing of the Republican Party opposes trade normalization and military cooperation with China, while liberals in the Democratic Party sometimes favor imposing sanctions on China for its human rights violations and its treatment of Tibet. | |

| − | + | Several of the anti-communist groups of the 1970s and 1980s still function. [[Freedom House]] continues to rate countries by their commitment to freedom and human rights, reporting that in today's world the [[Islamic nations]] have replaced communist countries as the greatest violators of [[human rights]]. The Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation reports on human rights abuses by such nations as Vietnam, China, and North Korea. ''The Washington Times'' is still a much-quoted general-interest newspaper which reports frequently on resurgent communism in Russia and military developments in China. In addition, new anti-communist organizations have sprung up to publicize new waves of repression in the remaining communist countries. On April 23, 2001, the ''New Republic,'' a leading liberal magazine which sometimes took hard-line anti-communist stands during the Cold War, published an article by its editors entitled: "It's Not Over: Why anti-communism still matters." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[[Cold War]] | *[[Cold War]] | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Marxism-Leninism]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[[Truman Doctrine]] | *[[Truman Doctrine]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | |

| − | * | + | * Brennan, Mary C. ''Wives, Mothers, and the Red Menace: Conservative Women and the Crusade against Communism.'' Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2008. ISBN 9780870818851 |

| − | * | + | * Cox, Terry. ''The Hungarian Uprising and Its Legacy in Eastern Europe.'' London: Routledge, 2008. ISBN 9780415449281 |

| − | * | + | * Evans, M. Stanton. ''Blacklisted by History: The Untold Story of Senator Joe McCarthy and His Fight against America's Enemies.'' New York: Crown Forum, 2007. ISBN 9781400081059 |

| + | * Haynes, John Earl. ''Red Scare or Red Menace?: American Communism and Anticommunism in the Cold War Era.'' (The American ways series.) Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996. ISBN 9781566630917 | ||

| + | * Heale, M. J. ''American Anticommunism: Combating the Enemy Within, 1830-1970. The American moment.'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990. ISBN 9780801840517 | ||

| + | * Powers, Richard Gid. ''Not Without Honor: The History of American Anticommunism.'' New York: Free Press, 1995. ISBN 9780029253014 | ||

| + | * Ruotsila, Markku. ''British and American Anticommunism Before the Cold War.'' (Cass series—Cold War history, 3.) London: Frank Cass, Routledge Publ. 2001. ISBN 9780714681771 | ||

| + | * Schrecker, Ellen. ''The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents.'' New York: Palgrave, 2002. ISBN 9780312393199 | ||

| + | * Schwarz, Fred. ''You Can Trust the Communists (to be Communists).'' [1960] Christian Anti-Communist Crusade, 1965. | ||

| + | * Waddington, Lorna Louise. ''Hitler's Crusade: Bolshevism and the Myth of the International Jewish Conspiracy.'' London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2007. ISBN 9781845115562 | ||

[[Category:politics]] | [[Category:politics]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:philosophy]] |

{{Credit|203581258}} | {{Credit|203581258}} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:13, 1 June 2019

Anti-communism refers to opposition to communism, especially Marxism-Leninism. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the growing power of the communist movement after the Soviet Union was established in 1917.

Monarchists, Christians, classical Liberals, social-democrats, and pro-free market forces in Europe opposed the first wave of communist revolutions from 1917 to 1922. Fascism and Nazism were based in part on a violent form of anti-communism. After World War II, the liberal democracies took the lead in opposing Soviet communism during the Cold War. The human rights movement of the late twentieth century added a strong moral component to the anti-communist cause, exposing gross abuses of human rights in the communist world. At the same time, military dictatorships sometimes used anti-communism as a justification for harsh repression of political opposition.

The country best known for being an opponent of communism is the United States, together with its long-time allies like the United Kingdom, Canada, France, and Australia. In addition to government policies to resist the spread of Soviet communism, anti-communist non-governmental organizations in these countries did much to heighten the world's awareness of communism.

The 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union was a major victory for the anti-communist cause, which generally viewed the USSR as the heart of the communist threat. Anti-communism today often focuses on exposing human rights abuses in the remaining Marxist-Leninist regimes and preventing extreme left-wing movements from taking over democratic nations.

The career of anti-communism

| Communism |

| Basic concepts |

| Marxist philosophy |

| Class struggle |

| Proletarian internationalism |

| Communist party |

| Ideologies |

| Marxism Leninism Maoism |

| Trotskyism Juche |

| Left Council |

| Religious Anarchist |

| Communist internationals |

| Communist League |

| First International |

| Comintern |

| Fourth International |

| Prominent communists |

| Karl Marx |

| Friedrich Engels |

| Rosa Luxemburg |

| Vladimir Lenin |

| Joseph Stalin |

| Leon Trotsky |

| Máo Zédōng |

| Related subjects |

| Anarchism |

| Anti-capitalism |

| Anti-communism |

| Communist state |

| Criticisms of communism |

| Democratic centralism |

| Dictatorship of the proletariat |

| History of communism |

| Left-wing politics |

| Luxemburgism |

| New Class New Left |

| Post-Communism |

| Eurocommunism |

| Titoism |

| Primitive communism |

| Socialism Stalinism |

| Socialist economics |

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the communist movement was at odds with the traditional monarchies that ruled over much of the European continent. At the time, monarchists and religious leaders who supported traditional monarchies were the most prominent anti-communists, and many European monarchies outlawed the public expression of communist views.

However, after World War I, several European monarchies were overthrown in a series of revolutions and military engagements. The most conservative European monarchy, the Russian empire, was replaced by the communist-run Soviet Union. The Russian Revolution also inspired and actively supported a series of other communist revolutions across Europe in the years of 1917-1922. The Soviet policy of ruthlessly repressing the new regime's opponents and treating religious leaders as enemies of the state, meanwhile, shocked much of the world.

The 1920s and 1930s saw the fading of traditionalist conservatism. The mantle of anti-communism was thus taken up by American-inspired Liberalism on the one hand and the rising fascist movements on the other. These became the "two faces" of anti-communism over the next several decades.

Since communism remained largely a European phenomenon, American anti-communist sentiments tended to follow their European counterparts. When communist groups and political parties began appearing elsewhere in the world, such as China in the late 1920s, their first opponents were usually either colonial authorities or local nationalist movements, often inspired by American democracy, but sometimes by fascism. Anti-communist dictatorships that were established in Europe in the late 1930s, such as the government of Francisco Franco in Spain, are considered to fall somewhere on the border between traditional conservatism and fascism.

During World War II, the liberal democracies set aside anti-communism in order to ally themselves with Stalin's Russia against Hitlerand Nazi Germany, and non-governmental organizations opposed to communism suffered a setback. After World War II, the Soviet Union became a superpower, and communism became a truly global phenomenon back by substantial military might, with a commitment to fomenting revolution throughout the capitalist world. This threat made anti-communism an integral part of the domestic and foreign policies of the United States and its NATO allies.

Winston Churchill warned the world that a communist "Iron Curtain" had fallen in Eastern Europe, while the United States considered anti-communism the top priority of its foreign policy. As the reality of Stalin's tyranny became more apparent, liberal anti-communism gained increasing moral authority. Meanwhile, conservatism in the post-war era abandoned its monarchist and aristocratic associations, focusing instead on the preservation of the free market, private property, human rights, the legitimate interests of large corporations, and the defense of traditional moral and religious values. This attitude became a cornerstone of American conservative thought in the 1940s and 1950s. The rise of Communist China raised the specter of communism taking over Asia, and the effort of the Soviet Union and China to foster revolution throughout the developing world made the communist threat a very real one in many people's minds.

The United States and its allies in the United Nations joined to oppose communist aggression during the Korean War, when the Stalinist North Korean regime of Kim Il-sung invaded the South in an attempt to unify the country under communist rule. During this time, American conservatives sought to combat what they saw as a growing communist influence at home. This led to the adoption of a number of repressive domestic policies that are collectively known under the term "McCarthyism."

In the 1960s, the United States attempted once again to stop the communist advance, this time in Vietnam. Unlike in Korea, where the north was the clear aggressor and the United States effort was highly popular among South Koreans, American forces in Vietnam found themselves mired in a less clear-cut situation. The United States ultimately withdrew from the conflict and allowed the communists to take over not only Vietnam, but Cambodia and Laos as well, resulting in terrible human losses, especially in Cambodia's "killing fields."

Throughout the Cold War, governments in Asia, Africa, and Latin America turned to the United States for political and economic support. Some of these were liberal democracies, but others were authoritarian regimes, which—according to their critics—used the fear of communism as a means of legitimizing repression.

During the 1970s, communist-led revolutions in South America, Africa, and Asia advanced in the wake of the United States failure in Vietnam. The United States often found itself supporting or tolerating repressive, sometimes racist, regimes who resisted Soviet—and Chinese—led insurgencies. The moral ambiguity of this situation often placed democratic anti-communists on the ethical defensive. On the other hand, dissidents in the Soviet Union added their voices to the anti-communist cause by exposing abuses of human rights such as the Gulag Archipelago. In the 1980s, the conservative governments of Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in Great Britain followed a strongly anti-Soviet foreign policy that is credited as a major factor in the fall of the Soviet Union and the democratization of Eastern Europe and other countries.

In the aftermath of the Cold War, communism is no longer seen as a major force in world politics. However, both liberals and conservatives express concerns over human rights abuses in China, Cuba, and North Korea; and anti-communist groups continue to struggle against resurgent far-leftism in such nations as Nicaragua and Venezuela.

Special types of anti-communism

Religious anti-communism

Soviet communism followed Karl Marx in teaching that religion was the "opiate of the masses" and thus actively sought to destroy religious institutions. The main target of communist "militant atheism" in the Soviet Union was usually the Russian Orthodox Church, but Catholics, Jews, Muslims, and Buddhists were also were persecuted. Thousands of priests and believers died when they resisted communist attempts to turn churches into "museums of atheism." The communists also murdered priests deemed ideologically hostile to socialism, especially those known to have been loyal to the tsar. A similar pattern emerged in China, Tibet, North Korea, North Vietnam, Mongolia and other communist strongholds, with Buddhists, Christians of various denominations, and others feeling the brunt of communist repression.

The Orthodox churches sometimes resisted the communists, but Orthodox leaders also were willing to compromise with the Soviet state, even to the degree of being suspected of working with the secret police to root out believers who were disloyal to Soviet policy. The relatively cooperative attitude of the Russian Orthodox Church resulted both from a desire to retain at least a few of its believers and protect its most sacred sites, and also from a long-standing attitude in the Orthodox tradition which held that the church and state should work in harmony with one another wherever possible. Nevertheless, Orthodox believers often spoke out against communism, and in the west many Orthodox Christians were active in anti-communist movements.

The Catholic Church, on the other hand, has a strong and official history of anti-communism dating back to well before the days of the Russian Revolution. In 1864, Pope Pius IX issued a Papal encyclical called Quanta Cura in which he called communism and socialism a "most fatal error." [1] PapalEncyclicals. Retrieved September 6, 2008. One factor in the later difference between the Catholic and Orthodox attitudes is that Catholicism's headquarters lay outside the Soviet Empire, in Rome. Additionally, from ancient times, the papacy had consistently confronted secular rulers it considered incompatible with the Catholic faith. In Hungary, Cardinal Josef Mindszenty became an international symbol of opposition to communist religious oppression, and Catholic leaders in other communist nations often rankled communist authorities. The best known of these today was the Polish cardinal Karol Wojtyła, who later became Pope John Paul II.

Protestants were often even more vocal in their opposition to communism. Without strong international backing, as compared to the Catholics, however, they lacked political leverage and were repressed by the communists in the most brutal manner. In the United States, groups such as the Christian Anti-Communism Crusade and the Voice of the Martyrs rose to alert Christians to the suffering of their fellow believers in the communist world.

In Tibet, the Dalai Lama became a symbol of communist repression of religion in Asia when the Chinese communist invaded Tibet and forced him into exile. Other Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and indigenous religious groups, though less known, face similar oppression.

Jews, too, faced repression in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Orthodox Jews faced serious persecution not unlike that of the Christians, while secular Jews faced job discrimination, and all Jews found it virtually impossible to leave the country. Jewish anti-communism in the West usually found expression in broader political movements such as social democracy and labor unions, but in the 1970s a large-scale campaign on behalf of Soviet Jewry found expression in Jewish synagogues. Jews were also in the forefront of the neo-conservative movement that became a prominent factor developing the Reagan administration's anti-communist foreign policy.

Fascist anti-communism

Fascism and Soviet Communism both arose to prominence after World War I. At the end of the war, socialist uprisings, or the threat of them, arose throughout Europe. In Germany, the Spartacist uprising of January 1919 failed, but in Bavaria, communists successfully overthrew the government and established the Bavarian Soviet Republic, which lasted for a few weeks in 1919. Similar short-lived Soviet republics emerged in other German states and a Soviet government was also briefly established in Hungary under Béla Kun in 1919. The Russian Revolution also inspired revolutionary movements in Italy, a wave of labor strikes in Britain, the Winnipeg General Strike in Canada, the Seattle General Strike in the United States, and other radical events.

Fascism was in part a reaction against these developments. Italian fascism, led by Benito Mussolini, took power in 1922 with the blessing of Italy's king after years of leftist unrest led many conservatives to fear that a communist revolution was a very real threat. Throughout Europe, numerous aristocrats and conservative intellectuals, as well as capitalists and industrialists, lent their support to fascist movements that arose in emulation of Italian fascism. Meanwhile, in Germany, numerous extreme right-wing nationalist groups arose, based in part on the threat of communism.

During the worldwide Great Depression of the 1930s, communist and fascist movements were bitterly and often violently opposed to each other. The most notable example of this conflict was the Spanish Civil War, which became in part a proxy war between the fascists and conservatives who backed Francisco Franco and the pro-Soviet communist movements (allied uneasily with anarchists and Trotskyists) which backed the Republican government and were aided materially by the Soviet Union.

Adolf Hitler, too, rose to power partly on the basis of his anti-communism, as well as his ideology of Aryan superiority and anti-Semitism. Indeed, much of Hitler's anti-Semitism focused on the alleged Jewish responsibility for the rise of communism.

Initially, the Soviet Union supported a coalition with the Western powers against Nazi Germany, as well as popular fronts in various countries against domestic fascism. The Munich Agreement between Germany, France, and Britain heightened Soviet fears that the Western powers were endeavoring to force them to bear the brunt of a war against Nazism. The Soviets thus negotiated a non-aggression pact with Germany—the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939, more commonly known as the Hitler-Stalin Pact.

Stalin was taken by surprise when Nazi Germany broke the pact and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 in Operation Barbarossa. Fascism and communism reverted to their relationship as lethal enemies, with the war—in the eyes of both sides—becoming one between their respective ideologies.

With the defeat of the Axis Powers, fascist anti-communism was dealt a death blow. However, fascist elements persisted in the world anti-communist movement, often to the dismay of its other components.

United States Anti-communism and the Cold War

Following World War II and the rise of the Soviet Union as a major world power, the objections to communism took on an added urgency. Many worried about the human rights of the millions of people who had recently come under communist rule in the wake of Stalin's policies. The fear of many anti-communists in the United States was that communism would eventually become a direct threat to the government of the United States. This view led to the so-called "domino theory," in which a communist takeover in certain nations could not be tolerated, because it could lead to a chain reaction which would result in a triumph of world communism. There were also fears, not unfounded, that powerful nations like the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China were using their power to create and support anti-democratic revolutions, as well as to forcibly assimilate formerly free nations into communist rule. The United States policy of halting further communist expansion, first enunciated by President Harry S. Truman, came to be known as "containment."

The United States government thus based its anti-communism both on national defense priorities and the human rights record of Communist states. These states killed millions of their own people in the course of ending capitalism and continued to suppress civil liberties of the surviving population.

The policy succeeded in stemming the communist advance in Korea in the early 1950s, but Cuba was lost to communism in 1959. Then, after the United States debacle in Vietnam, anti-communists despaired that their cause could prevail. However, during the presidency of Ronald Reagan, himself an ardent anti-communist of long standing, a surprising change took place. Calling the Soviet Union an "evil empire" and pursuing a policy of funding United States military superiority, Reagan pressured the Soviets to compete, to the point that their bankrupt economy began to collapse. Soon, the Berlin Wall had been torn down, the "Iron Curtain" began to rise, and the Soviet Union itself was no more.

Anti-communism and NGOs

A number of U.S. groups and publications worked to oppose communism during the Cold War. These include, in alphabetical order:

- Accuracy In Media: One of America's first media watchdog groups, A.I.M. focused especially on the mainstream media's lack of balance in reporting on anti-communist issues.

- AFL-CIO: America's largest labor federation was a bastion of anti-communism during the Vietnam era under its hard-nosed leader George Meany, whose invitation to Alexandre Solzhenitsyn to speak at AFL-CIO meetings brought awareness of Soviet human rights abuses to U.S. audiences.

- American Security Council: An anti-communist group in Washington that concentrated on the military dimension of the Cold War.

- Captive Nations Committee: A coalition of anti-communists which sponsored the annual Captive Nations Week, led for many years by Dr. Lev Dobriansky.

- Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation: A Catholic-based educational organization named after the famous Hungarian prelate who was persecuted in his home country and found sanctuary for several years in the United States Embassy.

- CAUSA International: The Unificationist successor to the Freedom Leadership Foundation, which created sophisticated anti-communist seminars during the 1980s, both in the United States and Latin America.

- Christian Anti-Communism Crusade: A U.S. educational organization led by Dr. Fred Schwarz, which engaged in large scale seminars focusing on communism's incompatibility with Christianity.

- Commentary Magazine: Founded by the American Jewish Committee in 1945, Commentary was a leading voice for liberal anti-communism and later became the principal organ of neo-conservatism.

- Committee on the Present Danger: Originally formed in the 1950s, the CPD was revived in 1972, involving a number of hard-line democrats as well as Republicans. It became a major influence on several U.S. administrations especially that of Ronald Reagan.

- Council Against Communist Aggression: A Washington D.C.-based group created to foster communication and networking among anti-communist groups and individuals in the nation's capital.

- Cuban Anti-Communist Groups: Various Cuban anti-communist movements ranged from groups such as Alpha 66 (a militant group accused of acts of violence and arson) to the more moderate Cuban American National Foundation.

- Freedom House: The oldest human rights group in the United States provided factual evidence and a ratings system that exposed communist countries as the greatest violators of freedom.

- Freedom Leadership Foundation: A Unificationist educational organization that promoted the cause of Soviet dissidents, confronted leftist groups on campus, and educated young people against Marxist ideology.

- Heritage Foundation: The leading conservative "think tank" in Washington, D.C.

- Human Events: A Washington-based conservative weekly tabloid newspaper and later a magazine.

- Hungarian Freedom Fighters Federation: An association of pro-democracy Hungarians who had supported their nation's unsuccessful resistance to communist aggression in 1956.

- National Alliance of Russian Solidarists: A Russian organization known by the acronym "NTS" and founded in 1930 by a group of young Russian anticommunists, led in the US by Constantin W. Boldyreff.

- National Committee for a Free Europe: Founded in 1949 in New York and dedicated to opposing Stalin's Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe, this group's main contribution was the founding of the government-supported broadcaster Radio Free Europe.

- National Review: A leading conservative magazine founded in New York by William F. Buckley, Jr. in 1955.

- The New Republic: A venerable liberal magazine which, though opposed to the Vietnam War, was strongly critical of both the Soviet Union and the New Left.

- Voice of the Martyrs: Founded by the persecuted Romanian pastor Richard Wurmbrandt and dedicated to publicizing the plight of Protestants and other Christians in Eastern Europe.

- U.S. Council for World Freedom: Created in the early 1970s to act as the United States coordinating committee to send delegations to the World Anti-Communist League meetings.

- The Washington Times A daily newspaper in Washington D.C., and later with a national weekly, founded by the Reverend Sun Myung Moon to balance the liberal influence of the Washington Post.

- Young Americans for Freedom: A group of young conservatives inspired by the presidential candidacy of Barry Goldwater which also engaged in debates and demonstrations on college campuses against communism.

- Young People's Social League: The youth arm of the Social Democrats USA, which had split with the United States Socialist Party over Vietnam. YPSL battled other socialist groups on campuses and provided a number of intellectual leaders known later as "neocons."

After the Cold War

Anti-communism became significantly muted after the fall of the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc communist regimes in Eastern and Central Europe between 1989 and 1991. The fear of a worldwide communist takeover is no longer a serious concern. Remnants of anti-communism remain, however, in United States foreign policy toward Cuba, mainland China, and North Korea. The growth of China as a major economic and military power is a major concern for some. The conservative wing of the Republican Party opposes trade normalization and military cooperation with China, while liberals in the Democratic Party sometimes favor imposing sanctions on China for its human rights violations and its treatment of Tibet.

Several of the anti-communist groups of the 1970s and 1980s still function. Freedom House continues to rate countries by their commitment to freedom and human rights, reporting that in today's world the Islamic nations have replaced communist countries as the greatest violators of human rights. The Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation reports on human rights abuses by such nations as Vietnam, China, and North Korea. The Washington Times is still a much-quoted general-interest newspaper which reports frequently on resurgent communism in Russia and military developments in China. In addition, new anti-communist organizations have sprung up to publicize new waves of repression in the remaining communist countries. On April 23, 2001, the New Republic, a leading liberal magazine which sometimes took hard-line anti-communist stands during the Cold War, published an article by its editors entitled: "It's Not Over: Why anti-communism still matters."

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brennan, Mary C. Wives, Mothers, and the Red Menace: Conservative Women and the Crusade against Communism. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2008. ISBN 9780870818851

- Cox, Terry. The Hungarian Uprising and Its Legacy in Eastern Europe. London: Routledge, 2008. ISBN 9780415449281

- Evans, M. Stanton. Blacklisted by History: The Untold Story of Senator Joe McCarthy and His Fight against America's Enemies. New York: Crown Forum, 2007. ISBN 9781400081059

- Haynes, John Earl. Red Scare or Red Menace?: American Communism and Anticommunism in the Cold War Era. (The American ways series.) Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996. ISBN 9781566630917

- Heale, M. J. American Anticommunism: Combating the Enemy Within, 1830-1970. The American moment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990. ISBN 9780801840517

- Powers, Richard Gid. Not Without Honor: The History of American Anticommunism. New York: Free Press, 1995. ISBN 9780029253014

- Ruotsila, Markku. British and American Anticommunism Before the Cold War. (Cass series—Cold War history, 3.) London: Frank Cass, Routledge Publ. 2001. ISBN 9780714681771

- Schrecker, Ellen. The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents. New York: Palgrave, 2002. ISBN 9780312393199

- Schwarz, Fred. You Can Trust the Communists (to be Communists). [1960] Christian Anti-Communist Crusade, 1965.

- Waddington, Lorna Louise. Hitler's Crusade: Bolshevism and the Myth of the International Jewish Conspiracy. London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2007. ISBN 9781845115562

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.