Haig, Alexander

| Line 173: | Line 173: | ||

===Falklands War=== | ===Falklands War=== | ||

| − | + | {{Main|Falklands War}} | |

| − | [[File:Haig and Thatcher DF-SC-83-06152.jpg|thumb|Haig as Secretary of State with [[British Prime Minister]] [[Margaret Thatcher]] at Andrews Air Force Base in 1982. | + | [[File:Haig and Thatcher DF-SC-83-06152.jpg|thumb|250px|Haig as Secretary of State with [[British Prime Minister]] [[Margaret Thatcher]] at Andrews Air Force Base in 1982.]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | In April 1982 Haig conducted [[shuttle diplomacy]] between the governments of [[Argentina]] in [[Buenos Aires]] and the [[United Kingdom]] in [[London]] after | + | In April 1982 Haig conducted [[shuttle diplomacy]] between the governments of [[Argentina]] in [[Buenos Aires]] and the [[United Kingdom]] in [[London]] after Argentina invaded the [[Falkland Islands]]. Negotiations broke down and Haig returned to Washington on April 19. The British [[Naval fleet|fleet]] then entered the war zone. |

| − | [[File:President Ronald Reagan during a meeting with Prime Minister Thatcher at 10 Downing Street.jpg|thumb| | + | |

| + | [[File:President Ronald Reagan during a meeting with Prime Minister Thatcher at 10 Downing Street.jpg|thumb|250px|Secretary of State Alexander Haig accompanying President Ronald Reagan during a meeting with [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|British Prime Minister]] [[Margaret Thatcher]] and [[Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs|British Foreign Minister]] [[Francis Pym]] at [[10 Downing Street]], June 8, 1982.]] | ||

===1982 Lebanon War=== | ===1982 Lebanon War=== | ||

Revision as of 16:37, 16 March 2021

Currently working on —Jennifer Tanabe February 2021.

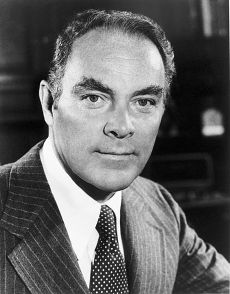

| Alexander Haig | |

| |

59th United States Secretary of State

| |

| In office January 22, 1981 – July 5, 1982 | |

| Deputy | William P. Clark Jr. Walter J. Stoessel Jr. |

|---|---|

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | Edmund Muskie |

| Succeeded by | George P. Shultz |

7th Supreme Allied Commander Europe

| |

| In office December 16, 1974 – July 1, 1979 | |

| Deputy | John Mogg Harry Tuzo Gerd Schmückle |

| President | Gerald Ford Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Andrew Goodpaster |

| Succeeded by | Bernard W. Rogers |

5th White House Chief of Staff

| |

| In office May 4, 1973 – September 21, 1974 | |

| President | Richard Nixon Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | H. R. Haldeman |

| Succeeded by | Donald Rumsfeld |

Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army

| |

| In office January 4, 1973 – May 4, 1973 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Bruce Palmer Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Frederick C. Weyand |

United States Deputy National Security Advisor

| |

| In office June 1970 – January 4, 1973 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Richard V. Allen |

| Succeeded by | Brent Scowcroft |

| Born | December 2 1924 Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | February 20 2010 (aged 85) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Patricia Fox (m.1950) |

| Children | 3 |

| Signature |

|

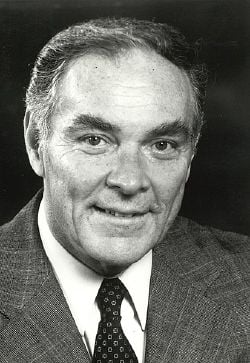

Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. (December 2, 1924 - February 20, 2010) was an American statesman and military leader. He retired as a general from the United States Army, where he served as an aide to General Alonzo Patrick Fox and General Edward Almond during the Korean War. During the Vietnam War, Haig commanded a battalion and later a brigade of the 1st Infantry Division. He then served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe, commanding all NATO forces in Europe.

After the 1973 resignation of H. R. Haldeman, Haig became President Nixon's chief of staff. Serving in the wake of the Watergate scandal, he became especially influential in the final months of Nixon's tenure, and played a role in persuading Nixon to resign in August 1974. He also served as the United States Secretary of State under President Ronald Reagan.

Life

Born in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, Haig served in the Korean War after graduating from the United States Military Academy.

Haig was born in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, the middle of three children of Alexander Meigs Haig Sr., a Republican lawyer of Scottish descent, and his wife, Regina Anne (née Murphy).[1] When Haig was 9, his father, aged 41, died of cancer. His Irish American mother raised her children in the Catholic faith.

Haig's younger brother, Frank Haig, became a Jesuit priest and professor emeritus of physics at Loyola University in Baltimore, Maryland.[2] Alexander Haig's sister, Regina Meredith, was a practicing attorney licensed in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, was elected a Mercer County, New Jersey Freeholder, and was a co-founding partner of the firm Meredith, Chase and Taggart, located in Princeton and Trenton, New Jersey. She died in 2008.

Haig initially attended Saint Joseph's Preparatory School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on scholarship; when it was withdrawn due to poor academic performance, he transferred to Lower Merion High School in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated in 1942.

Initially unable to secure his desired appointment to the United States Military Academy, Haig studied at the University of Notre Dame (where he reportedly earned a "string of A's" in an "intellectual awakening") for two years before securing a congressional appointment to the Academy in 1944 at the behest of his uncle, who served as the Philadelphia municipal government's director of public works.[3]

Enrolled in an accelerated wartime curriculum that de-emphasized the humanities and social sciences, Haig graduated in the bottom third of his class[4] (ranked 214 of 310) in 1947.[5] Although a West Point superintendent characterized Haig as "the last man in his class anyone expected to become the first general,"[6] other classmates acknowledged his "strong convictions and even stronger ambitions."[5]

Haig later earned an M.B.A. from the Columbia Business School in 1955 and an M.A. in international relations from Georgetown University in 1961. His thesis for the latter degree examined the role of military officers in making national policy.

Haig had an outstanding career as a military officer, serving in both the Korean War and the Vietnam War, and then as NATO Supreme Commander. As a young officer, he served as an aide to Lieutenant General Alonzo Patrick Fox, a deputy chief of staff to General Douglas MacArthur, and in 1950 he married Fox's daughter, Patricia. They had three children: Alexander Patrick Haig, Barbara Haig, and Brian Haig.[4]

Haig also served as Chief of Staff in the Nixon and Ford presidencies, as well as Secretary of State to Ronald Reagan.

In the 1980s and 1990s, being the head of a consulting firm, he served as a director for various struggling businesses, the best-known probably being computer manufacturer Commodore International.[7]

His memoirs, Inner Circles: How America Changed The World, were published in 1992.

On February 19, 2010, a hospital spokesman revealed that the 85-year-old Haig had been hospitalized at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore since January 28 and remained in critical condition.[8] On February 20, Haig died at the age of 85, from complications from a staphylococcal infection that he had prior to admission. According to The New York Times, his brother, Frank Haig, said the Army was coordinating a mass at Fort Myer in Washington and an interment at Arlington National Cemetery, but both had to be delayed by about two weeks owing to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.[4] A Mass of Christian Burial was held at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., on March 2, 2010, at which Henry Kissinger gave the eulogy.[9]

Early military career

Korean War

In the early days of the Korean War, Haig was responsible for maintaining General MacArthur's situation map and briefing MacArthur each evening on the day's battlefield events.[10] Haig later served (1950–1951) with the X Corps, as aide to MacArthur's chief of staff, General Edward Almond, who awarded Haig two Silver Stars and a Bronze Star with Valor device. Haig participated in four Korean War campaigns, including the Battle of Inchon, the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, and the evacuation of Hŭngnam, as Almond's aide.[10]

Pentagon assignments

Haig served as a staff officer in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations at the Pentagon (1962–1964), and then was appointed military assistant to Secretary of the Army Stephen Ailes in 1964. He then was appointed military assistant to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, continuing in that service until the end of 1965.[4] In 1966, Haig graduated from the United States Army War College.

Vietnam War

In 1966 Haig took command of a battalion of the 1st Infantry Division during the Vietnam War. On May 22, 1967, Lieutenant Colonel Haig was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the U.S. Army's second highest medal for valor, by General William Westmoreland as a result of his actions during the Battle of Ap Gu in March 1967. During the battle, Haig's troops (of the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment) became pinned down by a Viet Cong force that outnumbered U.S. forces by three to one. In an attempt to survey the battlefield, Haig boarded a helicopter and flew to the point of contact. His helicopter was subsequently shot down. Two days of bloody hand-to-hand combat ensued. An excerpt from Haig's official Army citation follows:

When two of his companies were engaged by a large hostile force, Colonel Haig landed amid a hail of fire, personally took charge of the units, called for artillery and air fire support and succeeded in soundly defeating the insurgent force ... the next day a barrage of 400 rounds was fired by the Viet Cong, but it was ineffective because of the warning and preparations by Colonel Haig. As the barrage subsided, a force three times larger than his began a series of human wave assaults on the camp. Heedless of the danger himself, Colonel Haig repeatedly braved intense hostile fire to survey the battlefield. His personal courage and determination, and his skillful employment of every defense and support tactic possible, inspired his men to fight with previously unimagined power. Although his force was outnumbered three to one, Colonel Haig succeeded in inflicting 592 casualties on the Viet Cong.[11]

Haig was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Purple Heart during his tour in Vietnam, and was eventually promoted to colonel as commander of 2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division.

Return to West Point

Following his one-year Vietnam tour, Haig returned to the United States to become regimental commander of the Third Regiment of the Corps of Cadets at West Point under the newly appointed commandant, Brigadier General Bernard W. Rogers. (Both had previously served together in the 1st Infantry Division, Rogers as assistant division commander and Haig as brigade commander.)

Security adviser (1969–1972)

In 1969, Haig was appointed military assistant to the assistant to the president for national security affairs, Henry Kissinger. A year later, he replaced Richard V. Allen as deputy assistant to the president for national security affairs. During this period, he was promoted to brigadier general (September 1969) and major general (March 1972).

In this position, Haig helped South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu negotiate the final cease-fire talks in 1972. Haig continued in this position until January 1973, when he became vice chief of staff of the Army (VCSA), the second-highest-ranking position in the Army. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate in October 1972, thus skipping the rank of lieutenant general. By appointing him to this billet, Nixon "passed over 240 generals" who were senior to Haig.[12]

White House Chief of Staff (1973–1974)

Nixon administration

After only four months as VCSA, Haig returned to the Nixon administration at the height of the Watergate affair as White House chief of staff in May 1973. Retaining his Army commission, he remained in the position until September 21, 1974, ultimately overseeing the transition to the presidency of Gerald Ford following Nixon's resignation on August 9, 1974.

Haig has been largely credited with keeping the government running while President Nixon was preoccupied with Watergate and was essentially seen as the "acting president" during Nixon's last few months in office.[4] During July and early August 1974, Haig played an instrumental role in finally persuading Nixon to resign. Haig presented several pardon options to Ford a few days before Nixon eventually resigned.

In this regard, in his 1999 book Shadow, author Bob Woodward describes Haig's role as the point man between Nixon and Ford during the final days of Nixon's presidency. According to Woodward, Haig played a major behind-the-scenes role in the delicate negotiations of the transfer of power from President Nixon to President Ford.[13][14] Indeed, about one month after taking office, Ford did pardon Nixon, resulting in much controversy. However, Haig denied the allegation that he played a key role in arbitrating Nixon's resignation by offering Ford's pardon to Nixon.[15][14]

Ford administration

Haig continued to serve as chief of staff for the first month of President Ford's tenure. He was then was replaced by Donald Rumsfeld. Author and Haig biographer Roger Morris, a former colleague of Haig's on the National Security Council early in Nixon's first term, wrote that when Ford pardoned Nixon, he in effect pardoned Haig as well.[16]

NATO Supreme Commander (1974–1979)

In December 1974, Haig was appointed as the next Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) by President Gerald Ford, replacing General Andrew Goodpaster, and he returned to active-duty within the United States Army. General Haig also became the top runner to be the 27th U.S. Army Chief of Staff, following the death of Army Chief of Staff General Creighton Abrams from complications of surgery to remove lung cancer on September 4, 1974. However it was General Frederick C. Weyand who later fulfilled the late General Abrams position as Army Chief of Staff instead of General Haig.[15]

Haig served as the the commander of NATO forces in Europe, and commander in chief of United States European Command for five years. He took the same route to SHAPE every day—a pattern of behavior that did not go unnoticed by terrorist groups. On June 25, 1979, Haig was the target of an assassination attempt in Mons, Belgium. A land mine blew up under the bridge on which Haig's car was traveling, narrowly missing Haig's car and wounding three of his bodyguards in a following car.[17] Authorities later attributed responsibility for the attack to the Red Army Faction (RAF). In 1993 a German court sentenced Rolf Clemens Wagner, a former RAF member, to life imprisonment for the assassination attempt.[17] Haig retired from his position as SACEUR in July 1979 and was succeeded by General Bernard W. Rogers.[15]

Civilian positions

After retiring from the Army as a four-star general in 1979, Haig moved on to civilian employment. In 1979 he worked at the Philadelphia-based Foreign Policy Research Institute briefly and later served on that organization's board.[18] Later that year, he was named president and director of United Technologies Corporation under Chief Executive Officer Harry J. Gray, a job he retained until 1981.

Secretary of State (1981–1982)

After Reagan won the 1980 presidential election, he nominated Haig to be his secretary of state.

Haig's prospects for Senate confirmation were clouded when Senate Democrats questioned his role in the Watergate scandal. Haig was eventually confirmed after hearings he described as an "ordeal," during which he received no encouragement from Reagan or his staff.[19]

Haig was the second career military officers to become secretary of state; George C. Marshall was the first, and after Haig Colin Powell also served in this position. Haig's speeches in this role in particular led to the coining of the neologism "Haigspeak," described as "Language characterized by pompous obscurity resulting from redundancy, the semantically strained use of words, and verbosity."[20]

Reagan assassination attempt: 'I am in control here'

In 1981, following the March 30 assassination attempt on Reagan, Haig asserted before reporters, "I am in control here." This assertion was met with a mixture of ridicule and alarm as his words were misinterpreted to mean he was taking over the presidency. [21] Haig was in fact directing White House crisis management as a result of Reagan's hospitalization, until Vice President George Bush arrived in Washington to assume that role:

Constitutionally gentlemen, you have the president, the vice president and the secretary of state, in that order, and should the president decide he wants to transfer the helm to the vice president, he will do so. As for now, I’m in control here, in the White House, pending the return of the vice president and in close touch with him. If something came up, I would check with him, of course.[22]

The U.S. Constitution, including both the presidential line of succession and the 25th Amendment, dictates what happens when a president is incapacitated. The Speaker of the House (at the time, Tip O'Neill, Democrat) and the president pro tempore of the Senate (at the time, Strom Thurmond, Republican), precede the secretary of state in the line of succession.

Haig later clarified his statement:

I wasn't talking about transition. I was talking about the executive branch, who is running the government. That was the question asked. It was not, "Who is in line should the president die?"[22]

Falklands War

In April 1982 Haig conducted shuttle diplomacy between the governments of Argentina in Buenos Aires and the United Kingdom in London after Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands. Negotiations broke down and Haig returned to Washington on April 19. The British fleet then entered the war zone.

1982 Lebanon War

Haig's report to Reagan on January 30, 1982, shows that Haig feared that the Israelis might start a war against Lebanon.[23] Critics accused Haig of "greenlighting" the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in June 1982. Haig denied this and said he urged restraint.[24]

Resignation

Haig caused some alarm with his suggestion that a "nuclear warning shot" in Europe might be effective in deterring the Soviet Union.[25] His tenure as secretary of state was often characterized by his clashes with the defense secretary, Caspar Weinberger. Haig, who repeatedly had difficulty with various members of the Reagan administration during his year-and-a-half in office, decided to resign his post on June 25, 1982.[26] President Reagan accepted his resignation on July 5.[27] Haig was succeeded by George P. Shultz, who was confirmed on July 16.[28]

1988 Republican presidential primaries

After leaving office, he unsuccessfully sought the presidential nomination in the 1988 Republican primaries. He also served as the head of a consulting firm and hosted the television program World Business Review.[29]

Haig ran unsuccessfully for the 1988 Republican Party presidential nomination. Although he enjoyed relatively high name recognition, Haig never broke out of single digits in national public opinion polls. He was a fierce critic of then–Vice President George H.W. Bush, often doubting Bush's leadership abilities, questioning his role in the Iran–Contra affair, and using the word "wimp" in relation to Bush in an October 1987 debate in Texas.[30] Despite extensive personal campaigning and paid advertising in New Hampshire, Haig remained stuck in last place in the polls. After finishing with less than 1 percent of the vote in the Iowa caucuses and trailing badly in the New Hampshire primary polls, Haig withdrew his candidacy and endorsed Senator Bob Dole.[31][32] Dole, steadily gaining on Bush after beating him handily a week earlier in the Iowa caucus, ended up losing to Bush in the New Hampshire primary by 10 percentage points. With his momentum regained, Bush easily won the nomination.

Later career

Haig was the host for several years of the television program World Business Review. At the time of his death, he was the host of 21st Century Business, with each program a weekly business education forum that included business solutions, expert interview, commentary, and field reports. Haig served as a founding member of the advisory board of Newsmax Media, which publishes the conservative web site, Newsmax.com.[33] Haig was co-chairman of the American Committee for Peace in the Caucasus, along with Zbigniew Brzezinski and Stephen J. Solarz. A member of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP) board of advisers, Haig was also a founding board member of America Online.[34]

On January 5, 2006, Haig participated in a meeting at the White House of former secretaries of defense and state to discuss U.S. foreign policy with Bush administration officials.[35] On May 12, 2006, Haig participated in a second White House meeting with 10 former secretaries of state and defense. The meeting included briefings by Donald Rumsfeld and Condoleezza Rice and was followed by a discussion with President George W. Bush.[36]

Legacy

Haig received numerous awards and decorations for his military service, including the Distinguished Service Cross, two Defense Distinguished Service Medals, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Navy Distinguished Service Medal, Air Force Distinguished Service Medal, two Silver Stars, three Legion of Merit awards, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, three Bronze Stars, and a Purple Heart. He was also awarded 1996 Distinguished Graduate Award by West Point.[37]

In 2009, General and Mrs. Haig were recognized for their generous gift in support of academic programs at West Point by being inducted into the Eisenhower Society for Lifetime Giving at the dedication of the Haig Room on the sixth floor of the new Jefferson Hall Library.[38]

Following Alexander Haig's death, President Barack Obama said in a statement that "General Haig exemplified our finest warrior–diplomat tradition of those who dedicate their lives to public service."[4] Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described Haig as a man who "served his country in many capacities for many years, earning honor on the battlefield, the confidence of presidents and prime ministers, and the thanks of a grateful nation."[39]

In his eulogy to Haig, Henry Kissinger said of his colleague of forty years:

Service was Al Haig’s mission. Courage was his defining characteristic. Patriotism was his motivating force.[9]

Notes

- ↑ James Hohmann, Alexander Haig, 85; soldier-statesman managed Nixon resignation The Washington Post, February 21, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ Albin Krebs and Robert Mcg. Thomas Jr., A Haig Inaugurated The New York Times, January 25, 1982. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ Adam Bellow, In Praise of Nepotism (Doubleday, 2003, ISBN 978-0385493888).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Tim Weiner, Alexander M. Haig Jr. Dies at 85; Was Forceful Aide to 2 Presidents The New York Times, February 20, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Harold Jackson, Alexander Haig obituary The Guardian, February 20, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ Dick Polman, Al Haig, the long goodbye The Philadelphia Enquirer, February 22, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ Dean Foust, Al Haig: Embattled In The Boardroom Businessweek, June 17, 1991. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ Haig, top adviser to 3 presidents, hospitalized The Seattle Times, February 19, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Henry A. Kissinger, Eulogy for General Alexander M. Haig, Jr. Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Alexander M. Haig, Jr., Lessons of the forgotten war History Central. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ↑ Elvin C. Bell, It Was a Good Road All the Way (Archway Publishing, 2020, ISBN 978-1480887930).

- ↑ Marjorie Hunter, 4‐Star Diplomat in White House Alexander Meigs Haig Jr The New York Times, May 5, 1973. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ↑ Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days (Simon & Schuster; Reissue edition, 2005, ISBN 978-0743274067).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bob Woodward, Shadow: Five Presidents And The Legacy Of Watergate (Simon & Schuster, 2000, ISBN 978-0684852638).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Alexander M. Haig, Inner Circles: How America Changed the World (Grand Central Pub., 1992, ISBN 978-0446515719).

- ↑ Roger Morris, Haig: The General's Progress (Robson, 1982, ISBN 978-0860511885).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 German Guilty in '79 Attack At NATO on Alexander Haig The New York Times, November 25, 1993. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ↑ Andrew Maykuth, Philadelphia dominated Haig's formative years The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 21, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ↑ James Chace, The Turbulent Tenure of Alexander Haig The New York Times, April 22, 1984. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ↑ John Algeo (ed.), Fifty Years among the New Words: A Dictionary of Neologisms 1941–1991 (Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0521413770).

- ↑ Michael Goodwin, The ‘anonymous official op-ed’ is less than it seems New York Post, September 6, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 The Day Reagan Was Shot CBS News, April 23, 2001. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ↑ Ronald Reagan edited by Douglas Brinkley (2007) The Reagan Diaries Harper Collins Template:ISBN p. 66 Saturday, January 30

- ↑ "Alexander Haig", Time, April 9, 1984.

- ↑ Waller, Douglas C. Congress and the Nuclear Freeze: An Inside Look at the Politics of a Mass Movement, 1987. Page 19.

- ↑ 1982 Year in Review: Alexander Haig Resigns

- ↑ Ajemian, Robert, "The Shakeup at State", Time, July 5, 1982.

- ↑ Short History of the Department of State, United States Department of State, Office of the Historian. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ↑ World Business Review (TV Series 1996–2006) - IMDb. Retrieved 2020-10-20

- ↑ "Haig, the Old Warrior, in New Battles", The New York Times, 21 November 1987.

- ↑ "Haig Calls Meeting to Discuss Campaign", Los Angeles Times, 12 February 1988.

- ↑ "Haig Drops Out of GOP Race, Endorses Dole", Los Angeles Times, 13 Feb 1988.

- ↑ General Alexander M. Haig, Jr. joins Newsmax.com advisory board, "PR Newswire", June 21, 2001.

- ↑ "Business Wire AOL-TIme Warner announces its board of directors", Business Wire, January 12, 2001.

- ↑ President George W. Bush poses for a photo Thursday, January 5, 2006, in the Oval Office with former secretaries of state and secretaries of defense from both Republican and Democratic administrations, following a meeting on the strategy for victory in Iraq. The White House (January 5, 2006).

- ↑ Bush discusses Iraq with former officials.

- ↑ 1996 Distinguished Graduate Award Citation: Alexander Meigs Haig, Jr. West Point Association of Graduates. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ↑ The Dedication of the Alexander M. Haig, Jr. Room West Point Class of 1947. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ↑ Nicholas Kralev, Alexander Haig, former secretary of state, dies at 85 The Washington Times, February 20, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Algeo, John (ed.). Fifty Years among the New Words: A Dictionary of Neologisms 1941–1991. Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521413770

- Bell, Elvin C. It Was a Good Road All the Way. Archway Publishing, 2020. ISBN 978-1480887930

- Bellow, Adam. In Praise of Nepotism. Doubleday, 2003. ISBN 978-0385493888

- Colodny, Len,and Robert Gettlin. Silent Coup: The Removal of a President. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0312051563

- Haig, Alexander M. Jr. Caveat: Realism, Reagan and Foreign Affairs. New York, NY: Scribner, 1984. ISBN 978-0025473706

- Haig, Alexander M. Jr. Inner Circles: How America Changed the World. Grand Central Pub., 1992. ISBN 978-0446515719

- Hersh, Seymour M. The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House. New York, NY: Summit Books, 1983. ISBN 978-0671447601

- Locker, Ray. Haig's Coup: How Richard Nixon's Closest Aide Forced Him from Office. Potomac Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1640120358

- Morris, Roger. Haig: The General's Progress. Robson, 1982. ISBN 978-0860511885

- Woodward, Bob. Shadow: Five Presidents And The Legacy Of Watergate. Simon & Schuster, 2000. ISBN 978-0684852638

- Woodward, Bob, and Carl Bernstein. The Final Days. Simon & Schuster; Reissue edition, 2005. ISBN 978-0743274067

External links

All links retrieved

- Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. (1924–2010)

- Alexander M. Haig, Jr. (White House Special Files: Staff Member and Office Files)

- Alexander Meigs Haig Hall of Valor: The Military Medals Database

- Alexander Haig U-S-History.com

- Alexander Haig obituary The Guardian

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Richard V. Allen |

Deputy National Security Advisor 1970–1973 |

Succeeded by: Brent Scowcroft |

| Preceded by: H. R. Haldeman |

White House Chief of Staff 1973–1974 |

Succeeded by: Donald Rumsfeld |

| Preceded by: Edmund Muskie |

United States Secretary of State 1981–1982 |

Succeeded by: George P. Shultz |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by: Bruce Palmer Jr. |

Vice Chief of Staff of the Army 1973 |

Succeeded by: Frederick C. Weyand |

| Preceded by: Andrew Goodpaster |

Supreme Allied Commander Europe 1974–1979 |

Succeeded by: Bernard W. Rogers |

| |||||||

Template:SACEUR

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.