Difference between revisions of "Raccoon" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Remove claimed tag) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) (added most recent Wikipedia version) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{About||other species called raccoon in the genus Procyon|Procyon (genus)|other uses|Raccoon (disambiguation)}} | |

| + | {{pp-move-indef}} | ||

{{Taxobox | {{Taxobox | ||

| − | |||

| name = Raccoon | | name = Raccoon | ||

| − | | image = Procyon lotor | + | | status = lc |

| − | | | + | | status_system = iucn3.1 |

| − | | | + | | status_ref = <ref name=iucn>{{IUCN2008|assessors=Timm, R., Cuarón, A.D., Reid, F. & Helgen, K. |year=2008|id=41686|title=Procyon lotor|downloaded=22 March 2009}} Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern</ref> |

| + | | image = Raccoon (Procyon lotor) 1.jpg | ||

| + | | image_caption = | ||

| + | | image_width = | ||

| regnum = [[Animal]]ia | | regnum = [[Animal]]ia | ||

| phylum = [[Chordate|Chordata]] | | phylum = [[Chordate|Chordata]] | ||

| − | | classis = [[ | + | | classis = [[Mammal]]ia |

| ordo = [[Carnivora]] | | ordo = [[Carnivora]] | ||

| familia = [[Procyonidae]] | | familia = [[Procyonidae]] | ||

| − | | genus = ''''' | + | | genus = ''[[Procyon (genus)|Procyon]]'' |

| − | | | + | | species = '''''P. lotor''''' |

| − | + | | binomial = ''Procyon lotor'' | |

| − | | | + | | binomial_authority = ([[Carolus Linnaeus|Linnaeus]], [[10th edition of Systema Naturae|1758]]) |

| − | | | + | | range_map = Raccoon-range.png |

| − | | | + | | range_map_caption = Native range in red, introduced range in blue |

| − | '' | + | | synonyms = '''''Ursus lotor''''' [[Linnaeus]], 1758 |

| − | '' | ||

| − | ''[[ | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | [[ | + | The '''raccoon''' ({{pron-en|ræˈkuːn|en-us-raccoon.ogg}}, ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes spelled as '''racoon''',<ref>{{cite book|last=Seidl|first=Jennifer|coauthors=McMordie, W.|editor=Fowler, F. G.; Fowler, H. W.; Sykes, John Bradbury|title=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English|publisher=Clarendon Press|location=Oxford|year=1982|isbn=978-0191958724|page=851}}</ref> also known as the '''common raccoon''',<ref>Zeveloff, p. 42</ref> '''North American raccoon''',<ref>Zeveloff, p. 1</ref> '''northern raccoon'''<ref>{{cite journal|last=Larivière|first=Serge|year=2004|title=Range expansion of raccoons in the Canadian prairies: review of hypotheses|journal=Wildlife Society Bulletin|volume=32|issue=3|pages=955–963|publisher=Allen Press|location=Lawrence, Kansas|issn = 0091-7648|doi=10.2193/0091-7648(2004)032[0955:REORIT]2.0.CO;2}}</ref> and colloquially as '''coon''',<ref>Zeveloff, p. 2</ref> is a medium-sized [[mammal]] native to North America. It is the largest of the [[procyonidae|procyonid]] family, having a body length of {{convert|40|to|70|cm|in|abbr=on}} and a body weight of {{convert|3.5|to|9|kg|lb|0|abbr=on}}. The raccoon is usually [[nocturnality|nocturnal]] and is [[omnivore|omnivorous]], with a diet consisting of about 40% [[invertebrate]]s, 33% [[plant]] foods, and 27% [[vertebrate]]s. It has a grayish coat, of which almost 90% is dense [[underfur]], which insulates against cold weather. Two of its most distinctive features are its extremely dexterous front [[paw]]s and its [[Domino mask|facial mask]], which are themes in the [[Native American mythology|mythology of several Native American tribes]]. Raccoons are noted for their intelligence, with studies showing that they are able to remember the solution to tasks up to three years later. |

| − | + | The original [[habitat]]s of the raccoon are [[deciduous]] and [[Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests|mixed forests]] of North America, but due to their adaptability they have extended their range to mountainous areas, [[Salt marsh|coastal marshes]], and [[urban area]]s, where many homeowners consider them to be pests. As a result of escapes and deliberate [[introduced species|introductions]] in the mid-20th century, raccoons are now also distributed across the European mainland, the [[Caucasus]] region and Japan. | |

| − | + | Though previously thought to be solitary, there is now evidence that raccoons engage in gender-specific [[social behavior]]. Related females often share a common area, while unrelated males live together in groups of up to four animals to maintain their positions against foreign males during the mating season, and other potential invaders. [[Home range]] sizes vary anywhere from 3 hectares for females in cities to 50 km<sup>2</sup> for males in [[prairie]]s (7 acres to 20 sq mi). After a [[gestation|gestation period]] of about 65 days, two to five young (known as a "kit", plural "kits") are born in spring. The kits are subsequently raised by their mother until dispersion in late fall. Although captive raccoons have been known to live over 20 years, their average life expectancy in the wild is only 1.8 to 3.1 years. In many areas hunting and traffic accidents are the two most common causes of death. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Etymology== | |

| + | [[File:Raccoon (Procyon lotor) 2.jpg|left|thumb|The mask of a raccoon is often interrupted by a brown-black streak that extends from forehead to nose.<ref>MacClintock, p. 5</ref>]] | ||

| − | + | The word "raccoon" was adopted into English from the native [[Powhatan language|Powhatan]] term, as used in the [[Virginia Colony]]. It was recorded on [[Captain John Smith]]'s list of Powhatan words as ''aroughcun'', and on that of [[William Strachey]] as ''arathkone''. It has also been identified as a [[Proto-Algonquian]] root ''*ahrah-koon-em'', meaning "[the] one who rubs, scrubs and scratches with its hands".<ref>Holmgren, p. 23; Zeveloff, p. 2</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Similarly, [[Spanish colonization of the Americas|Spanish colonists]] adopted the Spanish word {{lang|es|''mapache''}} from the [[Nahuatl]] ''mapachitli'' of the [[Aztec]]s, meaning "[the] one who takes everything in its hands".<ref>Holmgren, p. 52</ref> In many languages, the raccoon is named for its characteristic dousing behavior in conjunction with that language's term for ''bear'', for example {{lang|de|''Waschbär''}} in German, {{lang|it|''orsetto lavatore''}} in Italian and ''araiguma'' ({{lang|ja|アライグマ}}) in Japanese. In French and Portuguese (in Portugal), the washing behavior is combined with these languages' term for ''rat'', yielding, respectively, {{lang|fr|''raton laveur''}} and ''ratão-lavadeiro''. | |

| − | + | The [[colloquialism|colloquial]] abbreviation ''coon'' is used in words like ''coonskin'' for [[fur clothing]] and in phrases like ''old coon'' as a self-designation of [[animal trapping|trappers]].<ref>Holmgren, pp. 75–76; Zeveloff, p. 2</ref> However, the clipped form is also in use as an [[Ethnic slur#C|ethnic slur]].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,188830,00.html |title=Radio Talk Show Host Fired for Racial Slur Against Condoleezza Rice – Politics | Republican Party | Democratic Party | Political Spectrum |publisher=FOXNews.com |date=2006-03-22 |accessdate=2010-03-19}}</ref> The raccoon's scientific name, ''Procyon lotor'', is [[New Latin|neo-Latin]], meaning "before-dog washer", with ''lotor'' [[Latin]] for "washer" and ''Procyon'' Latinized [[Greek language|Greek]] from προ-, "before" and κύων, "dog". | |

| − | == | + | ==Taxonomy== |

| − | + | In the first decades after its discovery by the members of the expedition of [[Christopher Columbus]] – the first person to leave a written record about the species – [[taxonomy|taxonomists]] thought the raccoon was related to many different species, including [[Canidae|dogs]], [[Felidae|cats]], [[badger]]s and particularly [[bear]]s.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 47–67</ref> [[Carl Linnaeus]], the father of modern taxonomy, placed the raccoon in the genus ''[[Ursus (genus)|Ursus]]'', first as ''Ursus cauda elongata'' ("long-tailed bear") in the second edition of his ''[[Systema Naturae]]'', then as ''Ursus Lotor'' ("washer bear") in the tenth edition.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 64–67; Zeveloff, pp. 4–6</ref> In 1780, [[Gottlieb Conrad Christian Storr]] placed the raccoon in its own genus ''[[Procyon (genus)|Procyon]]'', which can be translated either to "before the dog" or "doglike".<ref>Holmgren, pp. 68–69; Zeveloff, p. 6</ref> It is also possible that Storr had its [[nocturnality|nocturnal]] lifestyle in mind and chose the star [[Procyon]] as eponym for the species.<ref>Hohmann, p. 44; Holmgren, p. 68</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Evolution== | |

| + | Based on [[fossil]] evidence from France and Germany, the first known members of the family ''[[Procyonidae]]'' lived in Europe in the late [[Oligocene]] about 25 million years ago.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 19</ref> Similar tooth and skull structures suggest procyonids and [[Mustelidae|weasels]] share a common ancestor, but molecular analysis indicates a closer relationship between raccoons and bears.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 16–18, 26</ref> After the then-existing species crossed the [[Bering Strait]] at least six million years later, the center of its distribution was probably in Central America.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 20, 23</ref> [[Coati]]s (''Nasua'' and ''Nasuella'') and raccoons (''Procyon'') have been considered to possibly share common descent from a species in the genus ''Paranasua'' present between 5.2 and 6.0 million years ago.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 24</ref> This assumption, based on morphological comparisons, conflicts with a 2006 genetic analysis which indicates raccoons are more closely related to [[Bassariscus|ringtails]].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Koepfli|first=Klaus-Peter|coauthors=Gompper, Matthew E.; Eizirik, Eduardo; Ho, Cheuk-Chung; Linden, Leif; Maldonado, Jesus E.; Wayne, Robert K.|year=2007|month=June|title=Phylogeny of the Procyonidae (Mammalia: Carnivora): Molecules, morphology and the Great American Interchange|journal=Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution|volume=43|issue=3|pages=1076–1095|publisher=Elsevier|location=Amsterdam|issn=1055-7903|url=http://si-pddr.si.edu/dspace/bitstream/10088/6026/1/Koepfli_2007phylogeny_of_the_procy.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-12-07|doi=10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.003|pmid=17174109}}</ref> Unlike other procyonids, such as the [[crab-eating raccoon]] (''Procyon cancrivorus''), the ancestors of the common raccoon left [[tropics|tropical]] and [[subtropics|subtropical]] areas and migrated farther north about 4 million years ago, in a migration that has been confirmed by the discovery in the [[Great Plains]] of fossils dating back to the middle of the [[Pliocene]].<ref>Hohmann, p. 46; Zeveloff, p. 24</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Subspecies== | |

| + | Four subspecies of raccoon [[Endemism|endemic]] to small Central American and [[Caribbean]] islands were often regarded as distinct species after their discovery. These are the [[Bahaman raccoon]] and [[Guadeloupe raccoon]], which are very similar to each other; the [[Tres Marias raccoon]], which is larger than average and has an angular skull; and the [[extinction|extinct]] [[Barbados raccoon]]. Studies of their morphological and genetic traits in 1999, 2003 and 2005 led all these [[island raccoon]]s to be listed as [[subspecies]] of the common raccoon in the third edition of ''[[Mammal Species of the World]]'' (2005).<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 42–46</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Helgen|first=Kristofer M.|coauthors=Wilson, Don E.|year=2003|month=January|title=Taxonomic status and conservation relevance of the raccoons (''Procyon'' spp.) of the West Indies|journal=Journal of Zoology|volume=259|issue=1|pages=69–76|publisher=The Zoological Society of London|location=Oxford|issn=0952-8369|doi=10.1017/S0952836902002972}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Helgen|first=Kristofer M.|coauthors=Wilson, Don E.|editor=Sánchez-Cordero, Víctor; Medellín, Rodrigo A.|title=Contribuciones mastozoológicas en homenaje a Bernardo Villa|url=http://books.google.com/?id=PQphdAd9KKcC|accessdate=2008-12-07|year=2005|publisher=Instituto de Ecología of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México|location=Mexico City|isbn=978-9703226030|page=230|chapter=A Systematic and Zoogeographic Overview of the Raccoons of Mexico and Central America}}</ref><ref>{{MSW3 Wozencraft|pages=627–628|id=14001658}}</ref> A fifth island raccoon population, the [[Cozumel raccoon]], which weighs only {{convert|3|to|4|kg|lb|1|abbr=on}} and has notably small teeth, is still regarded as a separate species. | ||

| − | + | The four smallest raccoon subspecies, with an average weight of {{convert|2|to|3|kg|lb|1|sp=us}}, are found along the southern coast of [[Florida]] and on the adjacent islands; an example is the Ten Thousand Island raccoon (''Procyon lotor marinus'').<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 59, 82–83</ref> Most of the other 15 subspecies differ only slightly from each other in coat color, size and other physical characteristics.<ref>MacClintock, p. 9; Zeveloff, pp. 79–89</ref> The two most widespread subspecies are the eastern raccoon (''Procyon lotor lotor'') and the upper Mississippi Valley raccoon (''Procyon lotor hirtus''). Both share a comparatively dark coat with long hairs, but the upper Mississippi Valley raccoon is larger than the eastern raccoon. The eastern raccoon occurs in all US states and Canadian provinces to the north of [[South Carolina]] and [[Tennessee]]. The adjacent range of the upper Mississippi Valley raccoon covers all US states and Canadian provinces to the north of [[Louisiana]], [[Texas]] and [[New Mexico]].<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 79–81, 84</ref> | |

| − | == | + | ==Description== |

| − | {{ | + | ===Physical characteristics=== |

| − | | | + | [[File:Waschbaer fg01.jpg|thumb|Track]] |

| − | | name = | + | [[File:Raccoonskull.jpg|thumb|left|Skull with dentition: 2/2 molars, 4/4 premolars, 1/1 canines, 3/3 incisors]] |

| − | | | + | [[File:Coonskeleton.jpg|thumb|Raccoon skeleton]] |

| − | | | + | Head to hindquarters, raccoons measure between {{convert|40|and|70|cm|in|0|abbr=on}}, not including the bushy tail which can measure between {{convert|20|and|40|cm|in|0|abbr=on}}, but is usually not much longer than {{convert|25|cm|in|0|abbr=on}}.<ref>Hohmann, p. 77; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 15; Zeveloff, p. 58</ref> The shoulder height is between {{convert|23|and|30|cm|in|0|abbr=on}}.<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, p. 16</ref> The skull of the adult male measures 94.3–125.8 mm long and 60.2–89.1 mm wide, while that of the female measures 89.4–115.9 mm long and 58.3–81.2 mm wide.<ref name="s1377">{{Harvnb|Heptner|Sludskii|2002|p=1377}}</ref> The body weight of an adult raccoon varies considerably with [[habitat]]; it can range from {{convert|2|to|14|kg|lb|sigfig=1}}, but is usually between {{convert|3.5|and|9|kg|lb|sigfig=1}}. The smallest specimens are found in Southern Florida, while those near the northern limits of the raccoon's range tend to be the largest (see [[Bergmann's rule]]).<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 58–59</ref> Males are usually 15 to 20% heavier than females.<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, p. 18</ref> At the beginning of winter, a raccoon can weigh twice as much as in spring because of fat storage.<ref>Hohmann, p.47–48; MacClintock, p. 44; Zeveloff, p. 108</ref> It is one of the most variably sized of all mammals. The heaviest recorded wild raccoon weighed {{convert|28.4|kg|lb|1|abbr=on}}, by far the largest weight recorded for a procyonid.<ref>MacClintock, p. 8; Zeveloff, p. 59</ref> |

| − | | | + | |

| − | | | + | The most characteristic physical feature of the raccoon is the area of black [[fur]] around the eyes, which contrasts sharply with the surrounding white face coloring. This is reminiscent of a "[[Domino mask|bandit's mask]]" and has thus enhanced the animal's reputation for mischief.<ref>Bartussek, p.6; Zeveloff, p. 61</ref> The slightly rounded ears are also bordered by white fur. Raccoons are assumed to recognize the facial expression and posture of other members of their species more quickly because of the conspicuous facial coloration and the alternating light and dark rings on the tail. The rings resemble those of a ringtail [[lemur]].<ref>Hohmann, pp. 65–66</ref><ref name="mc5-6z63" /> The dark mask may also reduce [[glare (vision)|glare]] and thus enhance [[night vision]].<ref name="mc5-6z63">MacClintock, pp. 5–6; Zeveloff, p. 63</ref> On other parts of the body, the long and stiff [[guard hair]]s, which shed moisture, are usually colored in shades of gray and, to a lesser extent, brown.<ref name="z60">Zeveloff, p. 60</ref> Raccoons with a very dark coat are more common in the German population because individuals with such coloring were among those initially released to the wild.<ref name="stellungnahme">{{cite web|url=http://www.projekt-waschbaer.de/aktuelles/stellungnahme/|title=Ökologische und ökonomische Bedeutung des Waschbären in Mitteleuropa – Eine Stellungnahme|accessdate=2008-12-07|last=Michler|first=Frank-Uwe|coauthors=Köhnemann, Berit A.|year=2008|month=May|work=„Projekt Waschbär“|language=German}} {{Dead link|date=October 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> The dense [[underfur]], which accounts for almost 90% of the coat, insulates against cold weather and is composed of {{convert|2|to|3|cm|in|1|abbr=on}} long hairs.<ref name="z60" /> |

| − | | | + | |

| − | | | + | [[File:Raccoonpenisbone.jpg|thumb|upright|Raccoon [[baculum]] or "penis bone"]] |

| − | | | + | The raccoon, whose method of [[Terrestrial locomotion|locomotion]] is usually considered to be [[plantigrade]], can stand on its hind legs to examine objects with its front paws.<ref>Hohmann, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 71–72</ref> As raccoons have short legs compared to their compact torso, they are usually not able either to run quickly or jump great distances.<ref>Hohmann, p. 93; Zeveloff, p. 72</ref> Their top speed over short distances is {{convert|16|to|24|km/h|mph|0|abbr=on}}.<ref>MacClintock, p. 28</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Saunders|first=Andrew D.|title=Adirondack Mammals|publisher=Syracuse University Press|location=Syracuse, New York|year=1989|month=March|isbn=978-0815681151|page=256| chapter=Raccoon|chapterurl=http://www.esf.edu/aec/adks/mammals/raccoon.htm}}</ref> Raccoons can swim with an average speed of about {{convert|5|km/h|mph|0|abbr=on}} and can stay in the water for several hours.<ref>MacClintock, p. 33; Zeveloff, p. 72</ref> For climbing down a tree headfirst—an unusual ability for a mammal of its size—a raccoon rotates its hind feet so they are pointing backwards.<ref>MacClintock, p. 30; Zeveloff, p. 72</ref> Raccoons have a dual cooling system to [[Thermoregulation|regulate their temperature]]; that is, they are able to both sweat and pant for heat dissipation.<ref>MacClintock, p. 29; Zeveloff, p. 73</ref> |

| − | | | + | |

| − | | | + | Raccoon skulls have a short and wide facial region and a voluminous [[braincase]]. The [[Facial skeleton|facial]] length of the skull is less than the [[Neurocranium|cranial]], and their [[nasal bone]]s are short and quite broad. The [[auditory bulla]]e are inflated in form, and the [[sagittal crest]] is weakly developed.<ref name="s1375">{{Harvnb|Heptner|Sludskii|2002|pp=1375–1376}}</ref> The [[dentition]]—40 teeth with the dental formula: <!-- {{dentition2|3.1.4.2|3.1.4.2}} —> {{DentalFormula|upper=3.1.4.2|lower=3.1.4.2}}—is adapted to their [[omnivore|omnivorous]] diet: the [[carnassial]]s are not as sharp and pointed as those of a full-time [[carnivore]], but the [[molar (tooth)|molars]] are not as wide as those of a [[herbivory|herbivore]].<ref>Zeveloff, p. 64</ref> The [[baculum|penis bone]] of males is about {{convert|10|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} long and strongly bent at the front end and is often used by biologists to classify reproductive status of specimens.<ref>Hohmann, p. 27; MacClintock, p. 84</ref> Seven of the thirteen identified vocal calls are used in [[Animal communication|communication]] between the mother and her kits, one of these being the birdlike twittering of newborns.<ref>Hohmann, p. 66; MacClintock, p. 92; Zeveloff, p. 73</ref> |

| − | | | + | {{Clear}} |

| − | | | + | |

| − | | | + | ===Senses=== |

| − | | | + | [[File:Mm Hand.jpg|thumb|Bottom side of the front paw with visible [[vibrissae]] on the tips of the digits]] |

| − | | | + | The most important sense for the raccoon is its [[Somatosensory system|sense of touch]].<ref>Bartussek, p. 13; Hohmann, p. 55; Zeveloff, p. 70</ref> The "hyper sensitive"<ref>Hohmann, p. 55</ref> front paws are protected by a thin [[Stratum corneum|horny layer]] which becomes pliable when wet.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 56–59; MacClintock, p. 15</ref> The five digits of the paws have no webbing between them, which is unusual for a [[carnivoran]].<ref>Zeveloff, p. 69</ref> Almost two-thirds of the area responsible for [[perception|sensory perception]] in the raccoon's [[cerebral cortex]] is specialized for the interpretation of tactile impulses, more than in any other studied animal.<ref>Hohmann, p. 56</ref> They are able to identify objects before touching them with [[vibrissa]]e located above their sharp, nonretractable [[claw]]s.<ref>Hohmann, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 70</ref> The raccoon's paws lack an opposable [[thumb]] and thus it does not have the agility of the hands of [[primate]]s.<ref>MacClintock, p. 15; Zeveloff, p. 70</ref> There is no observed negative effect on tactile perception when a raccoon stands in water below 10 °C (50 °F) for hours.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 60–62</ref> |

| − | | | + | |

| − | | | + | Raccoons are thought to be [[color blindness|color blind]] or at least poorly able to distinguish color, though their eyes are well-adapted for sensing green light.<ref>Hohmann, p. 63; MacClintock, p. 18; Zeveloff, p. 66</ref> Although their [[accommodation (eye)|accommodation]] of 11 [[dioptre]] is comparable to that of humans and they see well in twilight because of the [[tapetum lucidum]] behind the [[retina]], [[visual perception]] is of subordinate importance to raccoons because of their poor long-distance vision.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 63–65; MacClintock, pp. 18–21; Zeveloff, pp. 66–67</ref> In addition to being useful for orientation in the dark, their [[olfaction|sense of smell]] is important for intraspecific communication. Glandular [[secretion]]s (usually from their [[anal glands]]), urine and feces are used for marking.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 67–70; MacClintock, p. 17; Zeveloff, pp. 68–69</ref> With their broad [[hearing (sense)|auditory range]], they can perceive tones up to 50–85 [[Hertz|kHz]] as well as quiet noises like those produced by [[earthworm]]s underground.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 66, 72; Zeveloff, p. 68</ref> |

| − | }} | + | |

| + | ===Intelligence=== | ||

| + | Only a few studies have been undertaken to determine the mental abilities of raccoons, most of them based on the animal's sense of touch. In a study by the [[ethology|ethologist]] H. B. Davis in 1908, raccoons were able to open 11 of 13 complex locks in less than 10 tries and had no problems repeating the action when the locks were rearranged or turned upside down. Davis concluded they understood the [[abstraction|abstract]] principles of the locking mechanisms and their [[learning speed]] was equivalent to that of [[rhesus macaque]]s.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Davis|first=H. B.|year=1907|month=October|title=The Raccoon: A Study in Animal Intelligence|journal=The American Journal of Psychology|volume=18|issue=4|pages=447–489|publisher=University of Illinois Press|location=Champaign, Illinois|doi=10.2307/1412576|url=http://jstor.org/stable/1412576}}</ref> Studies in 1963, 1973, 1975 and 1992 concentrated on raccoon [[memory]] showed they can remember the solutions to tasks for up to three years.<ref name="h7172">Hohmann, pp. 71–72</ref> In a study by B. Pohl in 1992, raccoons were able to instantly differentiate between identical and different symbols three years after the short initial learning phase.<ref name="h7172"/> [[Stanislas Dehaene]] reports in his book ''The Number Sense'' raccoons can distinguish boxes containing two or four grapes from those containing three.<ref>{{cite book|last= Dehaene|first= Stanislas|title= The number sense|year=1997|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=New York|isbn=0-19-511004-8|page=12}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Behavior== | ||

| + | ===Social behavior=== | ||

| + | [[File:Raccons in a tree.jpg|thumb|Raccoons in a tree. The Raccoon's social structure is grouped into what [[Ulf Hohmann]] calls a "three class society".]] | ||

| + | Studies in the 1990s by the ethologists Stanley D. Gehrt and [[Ulf Hohmann]] indicated that raccoons engage in gender-specific [[social behavior]]s and are not typically solitary, as was previously thought.<ref name="gehrt">{{cite journal|last=Gehrt|first=Stanley D.|title=Raccoon social organization in South Texas|year= 1994}} (Dissertation at the University of Missouri-Columbia)</ref><ref>Hohmann, pp. 133–155</ref> Related females often live in a so-called "[[fission-fusion society]]", that is, they share a common area and occasionally meet at feeding or resting grounds.<ref>Bartussek, pp. 10–12; Hohmann, pp. 141–142</ref> Unrelated males often form loose ''male social groups'' to maintain their position against foreign males during the [[mating season]] – or against other potential invaders.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 152–154</ref> Such a group does not usually consist of more than four individuals.<ref>Bartussek, p. 12; Hohmann, p. 140</ref> Since some males show aggressive behavior towards unrelated kits, mothers will isolate themselves from other raccoons until their kits are big enough to defend themselves.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 124–126, 155</ref> With respect to these three different modes of life prevalent among raccoons, Hohmann called their [[social structure]] a "three class society".<ref>Hohmann, p. 133</ref> Samuel I. Zeveloff, professor of [[zoology]] at [[Weber State University]] and author of the book ''Raccoons: A Natural History'', is more cautious in his interpretation and concludes at least the females are solitary most of the time and, according to Erik K. Fritzell's study in [[North Dakota]] in 1978, males in areas with low population densities are as well.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 137–139</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The shape and size of a raccoon's [[home range]] varies depending on age, gender, and habitat, with adults claiming areas more than twice as large as juveniles.<ref>MacClintock, p. 61</ref> While the size of home ranges in the inhospitable habitat of North Dakota's [[prairie]]s lay between {{convert|7|and|50|km2|sqmi|sigfig=1|abbr=on}} for males and between {{convert|2|and|16|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=on}} for females, the average size in a [[marsh]] at [[Lake Erie]] was {{convert|0.49|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}.<ref>MacClintock, pp. 60–61</ref> Irrespective of whether the home ranges of adjacent groups overlap, they are most likely not actively defended outside the mating season if food supplies are sufficient.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 137–138</ref> Odor marks on prominent spots are assumed to establish home ranges and identify individuals.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 68–69</ref> Urine and feces left at shared latrines may provide additional information about feeding grounds, since raccoons were observed to meet there later for collective eating, sleeping and playing.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 142–147</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Concerning the general behavior patterns of raccoons, Gehrt points out "typically you'll find 10 to 15 percent that will do the opposite"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://chicagowildernessmag.org/issues/summer2002/raccoons.html|title=The City Raccoon and the Country Raccoon|accessdate=2008-12-07|last=Riddell|first=Jill|year=2002|work=Chicago Wilderness Magazine|publisher=Chicago Wilderness Magazine}}</ref> of what is expected. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Diet=== | ||

| + | Though usually nocturnal, the raccoon is sometimes active in daylight to take advantage of available food sources.<ref name="b10z99">Bartussek, p. 10; Zeveloff, p. 99</ref> Its diet consists of about 40% [[invertebrate]]s, 33% [[plant]] material and 27% [[vertebrate]]s.<ref>Hohmann, p. 82</ref> Since its diet consists of such a variety of different foods, Zeveloff argues the raccoon "may well be one of the world's most omnivorous animals".<ref>Zeveloff, p. 102</ref> While its diet in spring and early summer consists mostly of insects, worms, and other animals already available early in the year, it prefers fruits and nuts, such as [[acorn]]s and walnuts, which emerge in late summer and autumn, and represent a rich calorie source for building up fat needed for winter.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 85–88; MacClintock, pp. 44–45</ref> They eat active or large prey, such as [[bird]]s and [[mammal]]s, only occasionally, since they prefer prey which is easier to catch, specifically [[fish]] and [[amphibian]]s.<ref>Hohmann, p. 83</ref> Bird nests (eggs and after hatchlings) are frequently preyed on, and small birds are often helpless to prevent the attacking raccoon.<ref>http://www.birdfeedersdirect.com/backyard-feeder-pests/raccoons.aspx</ref> When food is plentiful, raccoons can develop strong individual preferences for specific foods.<ref>MacClintock, p. 44</ref> In the northern parts of their range, raccoons go into a [[winter rest]], reducing their activity drastically as long as a permanent snow cover makes searching for food impossible.<ref>MacClintock, pp. 108–113</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Dousing=== | ||

| + | [[File:Procyon lotor 7 - am Wasser.jpg|thumb|right|upright|Captive raccoons often douse their food before eating.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Raccoons sample food and other objects with their front paws to examine them and to remove unwanted parts. The tactile sensitivity of their paws is increased if this action is performed underwater, since the water softens the horny layer covering the paws.<ref>Hohmann, p. 55; Zeveloff, p. 7</ref> However, the behavior observed in captive raccoons in which they carry their food to a watering hole to "wash" or douse it before eating has not been observed in the wild.<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41; MacClintock, pp. 56–57</ref> [[Natural history|Naturalist]] [[Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon]] (1707–1788) believed that raccoons do not have adequate [[salivary gland|saliva production]] to moisten food, necessitating dousing, but this is certainly incorrect.<ref>Holmgren, p. 70; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41; MacClintock, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 7</ref> Captive raccoons douse their food more frequently when a watering hole with a layout similar to a stream is not farther away than {{convert|3|m|ft|0|abbr=on}}.<ref name="mc57">MacClintock, p. 57</ref> The widely accepted theory is that dousing is a [[vacuum activity]] imitating foraging at shores for aquatic foods.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 44–45; Lagoni-Hansen, pp. 41–42; MacClintock, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 7</ref> This is supported by the observation that such foods are doused more frequently. Cleaning dirty food does not seem to be a reason for "washing".<ref name="mc57" /> Experts have cast doubt on the veracity of observations of wild raccoons dousing food.<ref>Holmgren, p. 22 (pro); Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41 (contra); MacClintock, p. 57 (contra)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Reproduction=== | ||

| + | Raccoons usually [[mating|mate]] in a period triggered by increasing daylight between late January and mid-March.<ref>Hohmann, p. 150; MacClintock, p. 81; Zeveloff, p. 122</ref> However, there are large regional differences which are not completely explicable by solar conditions. For example, while raccoons in southern states typically mate later than average, the mating season in [[Manitoba]] also peaks later than usual in March and extends until June.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 122</ref> During the mating season, males roam their home ranges in search of females in an attempt to court them during the three to four day period when conception is possible. These encounters will often occur at central meeting places.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 148–150; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 47; MacClintock, pp. 81–82</ref> [[Sexual intercourse|Copulation]], including foreplay, can last over an hour and is repeated over several nights.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 150–151</ref> The weaker members of a ''male social group'' also are assumed to get the opportunity to mate, since the stronger ones cannot mate with all available females.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 153–154</ref> In a study in southern Texas during the mating seasons from 1990 to 1992, about one third of all females mated with more than one male.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Gehrt|first=Stanley|coauthors=Fritzell, Erik K.|year=1999|month=March|title=Behavioural aspects of the raccoon mating system: determinants of consortship success|journal=Animal behaviour|volume=57|issue=3|pages=593–601|publisher=Elsevier|location=Amsterdam|issn=0003-3472|doi=10.1006/anbe.1998.1037|pmid=10196048}}</ref> If a female does not become [[pregnancy|pregnant]] or if she loses her kits early, she will sometimes become fertile again 80 to 140 days later.<ref>Hohmann, p. 125; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 45; Zeveloff, p. 125</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Common Raccoon (Procyon lotor) in Northwest Indiana.jpg|left|thumb|A kit]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | After usually 63 to 65 days of [[gestation]] (although anywhere from 54 to 70 days is possible), a [[litter (animal)|litter]] of typically two to five young is born.<ref>Hohmann, p. 131; Zeveloff, pp. 121, 126</ref> The average litter size varies widely with habitat, ranging from 2.5 in [[Alabama]] to 4.8 in [[North Dakota]].<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, p. 50; Zeveloff, p. 126</ref> Larger litters are more common in areas with a high mortality rate, due, for example, to [[hunting]] or severe winters.<ref>Bartussek, p. 32; Zeveloff, p. 126</ref> While male yearlings usually reach their sexual maturity only after the main mating season, female yearlings can compensate for high mortality rates and may be responsible for about 50% of all young born in a year.<ref>Hohmann, p. 163; MacClintock, p. 82; Zeveloff, pp. 123–127</ref> Males have no part in raising young.<ref>Bartussek, p. 12; Hohmann, p. 111; MacClintock, p. 83</ref> The kits (also called "cubs") are blind and deaf at birth, but their mask is already visible against their light fur.<ref name="zp127">Hohmann, pp. 114, 117; Zeveloff, p. 127</ref> The birth weight of the about {{convert|10|cm|in|0|abbr=on}}-long kits is between {{convert|60|and|75|g|oz|1|abbr=on}}.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 127</ref> Their ear canals open after around 18 to 23 days, a few days before their eyes open for the first time.<ref>Hohmann, p. 117</ref> Once the kits weigh about {{convert|1|kg|lb|0|abbr=on}}, they begin to explore outside the den, consuming solid food for the first time after six to nine weeks.<ref>Hohmann, p. 119; MacClintock, pp. 94–95</ref> After this point, their mother [[Lactation|suckles]] them with decreasing frequency; they are usually weaned by 16 weeks.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 129</ref> In the fall, after their mother has shown them dens and feeding grounds, the juvenile group splits up.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 126–127. Zeveloff, p. 130</ref> While many females will stay close to the home range of their mother, males can sometimes move more than {{convert|20|km|mi|0|abbr=on}} away.<ref>Hohmann, p. 130; Zeveloff, pp. 132–133</ref> This is considered an [[instinct]]ive behavior, preventing [[inbreeding]].<ref>Hohmann, p. 128; Zeveloff, p. 133</ref> However, mother and offspring may share a den during the first winter in cold areas.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 130</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Life expectancy=== | ||

| + | [[File:Raccoon in Bear Country USA.ogg|thumb|Captive raccoons like this one in Bear Country USA are known to live for more than 20 years.]] | ||

| + | Captive raccoons have been known to live for more than 20 years.<ref>Bartussek, p. 6</ref> However, the species' life expectancy in the wild is only 1.8 to 3.1 years, depending on the local conditions in terms of traffic volume, hunting, and weather severity.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 118–119</ref> It is not unusual for only half of the young born in one year to survive a full year.<ref>Hohmann, p. 163; Zeveloff, p. 119</ref> After this point, the annual mortality rate drops to between 10% and 30%.<ref>Hohmann, p. 163</ref> Young raccoons are vulnerable to losing their mother and to starvation, particularly in long and cold winters.<ref>MacClintock, p. 73</ref> The most frequent natural cause of death in the North American raccoon population is [[Canine distemper|distemper]], which can reach [[epidemic]] proportions and kill most of a local raccoon population.<ref name="ergebnisse">{{cite web|url=http://www.projekt-waschbaer.de/erste-ergebnisse/|title=Erste Ergebnisse|accessdate=2008-12-07|last=Michler|first=Frank-Uwe|coauthors=Köhnemann, Berit A.|year=2008|month=June|work=„Projekt Waschbär“|language=German}}</ref> In areas with heavy vehicular traffic and extensive hunting, these factors can account for up to 90% of all deaths of adult raccoons.<ref>Hohmann, p. 162</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The most important natural [[predation|predators]] of the raccoon are [[bobcat]]s, [[coyote]]s, and [[great horned owl]]s, the latter mainly prey on young raccoons. In the [[Chesapeake Bay]], raccoons are the most important mammalian prey for [[bald eagle]]s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/506/articles/foodhabits |title=Birds of North America Online |publisher=Bna.birds.cornell.edu |accessdate=2010-03-19}}</ref> In their introduced range in the former Soviet Union, their main predators are [[wolf|wolves]], [[Eurasian lynx|lynx]]es and [[eagle owl]]s.<ref name="s1390">{{Harvnb|Heptner|Sludskii|2002|p=1390}}</ref> However, predation is not a significant cause of death, especially because larger predators have been [[Holocene extinction event|exterminated]] in many areas inhabited by raccoons.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 111–112</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Range== | ||

| + | ===Habitat=== | ||

| + | [[File:Northern Raccoons in tree.jpg|right|thumb|Taking refuge in a tree, [[Ottawa]], [[Ontario]]]] | ||

| + | Although they have thrived in sparsely wooded areas in the last decades, raccoons depend on vertical structures to climb when they feel threatened.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 93–94; Zeveloff, p. 93</ref> Therefore, they avoid open terrain and areas with high concentrations of [[beech|beech trees]], as beech [[bark]] is too smooth to climb.<ref>Hohmann, p. 94</ref> [[Tree hollow]]s in old [[oak]]s or other trees and rock crevices are preferred by raccoons as sleeping, winter and litter dens. If such dens are unavailable or accessing them is inconvenient, raccoons use [[burrow]]s dug by other mammals, dense [[undergrowth]], roadside culverts in urban areas, or tree crotches.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 97–101; Zeveloff, pp. 95–96</ref> In a study in the [[Solling]] range of hills in Germany, more than 60% of all sleeping places were used only once, but those used at least ten times accounted for about 70% of all uses.<ref>Hohmann, p. 98</ref> Since amphibians, [[crustacean]]s, and other animals found around the shore of lakes and rivers are an important part of the raccoon's diet, lowland [[deciduous]] or [[Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests|mixed forests]] abundant with water and marshes sustain the highest population densities.<ref>Hohmann, p. 160; Zeveloff, p. 98</ref> While population densities range from 0.5 to 3.2 animals per square kilometre (0.2 – 1.2 animals per square mile) in prairies and do not usually exceed 6 animals per square kilometer (2.3 animals per square mile) in upland hardwood forests, more than 20 raccoons per square kilometer (50 animals per square mile) can live in lowland forests and marshes.<ref>Hohmann, p. 160; Zeveloff, p. 97</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Distribution in North America=== | ||

| + | Raccoons are common throughout North America from Canada to [[Panama]], where the subspecies ''P. l. pumilus'' coexists with the [[crab-eating Raccoon]] (''P. cancrivorus'').<ref>Hohmann, pp. 12, 46; Zeveloff, pp. 75, 88</ref> The population on [[Hispaniola]] was exterminated as early as 1513 by Spanish colonists who hunted them for their meat.<ref>Holmgren, p. 58</ref> Raccoons were also exterminated in [[Cuba]] and [[Jamaica]], where the last sightings were reported in 1687.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 58–59</ref> The [[Bahaman raccoon]] (''P. l. maynardi'') was classified as [[endangered species|endangered]] by the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature|IUCN]] in 1996.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 42–45</ref>[[File:Racoon (20091106).JPG|thumb|alt=racoon|Racoon in the middle of the night looking for food (Sierra-Nevada Mountains, California)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is evidence that in [[pre-Columbian]] times raccoons were numerous only along rivers and in the woodlands of the [[Southeastern United States]].<ref>Zeveloff, p. 77</ref> As raccoons were not mentioned in earlier reports of [[American pioneer|pioneers]] exploring the central and north-central parts of the United States,<ref>Zeveloff, p. 78</ref> their initial spread may have begun a few decades before the 20th century. Since the 1950s, raccoons have expanded their range from [[Vancouver Island]]—formerly the northernmost limit of their range—far into the northern portions of the four south-central Canadian provinces.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 75</ref> New habitats which have recently been occupied by raccoons (aside from urban areas) include mountain ranges, such as the [[Western Rocky Mountains]], prairies and [[Salt marsh|coastal marshes]].<ref>Zeveloff, p. 76</ref> After a population explosion starting in the 1940s, the estimated number of raccoons in North America in the late 1980s was 15 to 20 times higher than in the 1930s, when raccoons were comparatively rare.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 75–76</ref> [[Urbanization]], the expansion of [[agriculture]], deliberate introductions, and the extermination of natural predators of the raccoon have probably caused this increase in abundance and distribution.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 76–78</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Distribution outside North America=== | ||

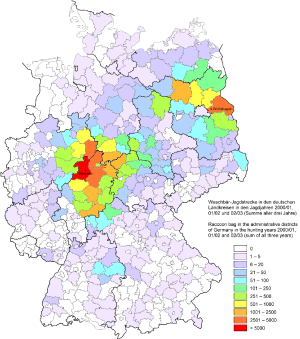

| + | [[File:Waschbaer-verbreitung.png|right|thumb|Distribution in Germany: Raccoons killed or found dead by hunters in the hunting years 2000/01, 01/02 and 02/03 in the administrative districts of Germany]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a result of escapes and deliberate [[introduced species|introductions]] in the mid-20th century, the raccoon is now distributed in several European and Asian countries. Sightings have occurred in all the countries bordering Germany, which hosts the largest population outside of North America.<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, pp. 89–90</ref> Another stable population exists in northern France, where several pet raccoons were released by members of the [[United States Air Force|U.S. Air Force]] near the [[Laon-Couvron Air Base]] in 1966.<ref>Hohmann, p. 13</ref> About 1,240 animals were released in nine regions of the former [[Soviet Union]] between 1936 and 1958 for the purpose of establishing a population to be hunted for their fur. Two of these introductions were successful: one in the south of [[Belarus]] between 1954 and 1958, and another in [[Azerbaijan]] between 1941 and 1957. With a seasonal harvest of between 1,000 and 1,500 animals, in 1974 the estimated size of the population distributed in the [[Caucasus]] region was around 20,000 animals and the density was four animals per square kilometer (10 animals per square mile).<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, pp. 90–92</ref> In Japan, up to 1,500 raccoons were imported as pets each year after the success of the [[anime]] series ''[[Rascal the Raccoon]]'' (1977). In 2004, the descendants of discarded or escaped animals lived in 42 of 47 [[Prefectures of Japan|prefectures]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20040916f1.html|title=Raccoons – new foreign menace?|accessdate=2008-12-07|last=Yoshida|first=Reiji|date=2004-09-16|work=The Japan Times Online|publisher=The Japan Times Ltd.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20080219a5.html|title=Raccoons take big bite out of crops|accessdate=2008-12-07|date=2008-02-19|work=The Japan Times Online|publisher=The Japan Times Ltd.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Ikeda|first=Tohru|coauthors=Asano, Makoto; Matoba, Yohei, Abe, Go|year=2004|title=Present Status of Invasive Alien Raccoon and its Impact in Japan|journal=Global Environmental Research|volume=8|issue=2|pages=125–131|publisher=Center for Global Environmental Research, National Institute for Environmental Studies|location=Tsukuba, Japan|issn=1343-8808|url=http://www.airies.or.jp/publication/ger/pdf/08-02-03.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-12-07}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Distribution in Germany==== | ||

| + | On April 12, 1934, two pairs of pet raccoons were released into the German countryside at the [[Edersee]] reservoir in the north of [[Hesse]] by forest superintendent Wilhelm Freiherr Sittich von Berlepsch, upon request of their owner, the poultry farmer Rolf Haag.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 9–10</ref> He released them two weeks before receiving permission from the [[Prussia]]n hunting office to "enrich the [[fauna]]", as Haag's request stated.<ref>Hohmann, p. 10</ref> Several prior attempts to introduce raccoons in Germany were not successful.<ref>Hohmann, p. 11; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 84</ref> A second population was established in [[East Germany]] in 1945 when 25 raccoons escaped from a [[fur farming|fur farm]] at Wolfshagen east of Berlin after an air strike. The two populations are parasitologically distinguishable: 70% of the raccoons of the Hessian population are infected with the [[Nematode|roundworm]] ''[[Baylisascaris procyonis]]'', but none of the [[Brandenburg]]ian population has the parasite.<ref name=autogenerated1>Hohmann, p. 182</ref> The estimated number of raccoons was 285 animals in the Hessian region in 1956, over 20,000 animals in the Hessian region in 1970 and between 200,000 and 400,000 animals in the whole of Germany in 2008.<ref name="ergebnisse" /><ref>Hohmann, p. 11</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The raccoon was a protected species in Germany, but has been declared a [[game (food)|game animal]] in 14 [[States of Germany|states]] since 1954.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 18, 21</ref> Hunters and [[environmentalism|environmentalists]] argue the raccoon spreads uncontrollably, threatens protected bird species and supersedes domestic [[carnivora]]ns.<ref name="stellungnahme" /> This view is opposed by the zoologist Frank-Uwe Michler, who finds no evidence a high population density of raccoons has negative effects on the [[biodiversity]] of an area.<ref name="stellungnahme" /> Hohmann holds extensive hunting cannot be justified by the absence of natural predators, because predation is not a significant cause of death in the North American raccoon population.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 14–16</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Distribution in the former USSR==== | ||

| + | Experiments in acclimatising raccoons into the USSR began in 1936, and were repeated a further 25 times until 1962. Overall, 1,222 individuals were released, 64 of which came from zoos and fur farms (38 of them having been imports from western Europe). The remainder originated from a population previously established in [[Transcaucasia]]. The range of Soviet raccoons was never single or continuous, as they were often introduced to different locations far from each other. All introductions into the [[Russian Far East]] failed ; melanistic raccoons were released on Petrov Island near [[Vladivostok]] and some areas of southern [[Primorye]], but died. In [[Middle Asia]], raccoons were released in [[Kyrgyztan]]'s [[Jalal-Abad Province]], though they were later recorded as "practically absent" there in January 1963. A large and stable raccoon population (yielding 1000–1500 catches a year) was established in [[Azerbaijan]] after an introduction to the area in 1937. Raccoons apparently survived an introduction near [[Terek River|Terek]], along the [[Sulak River]] into the [[Dagestan]]i lowlands. Attempts to settle racoons on the [[Kuban River]]'s left tributary and [[Kabardino-Balkaria]] were unsuccessful. A successful acclimatization occurred in [[Belarus]], where three introductions (consisting of 52, 37 and 38 individuals in 1954 and 1958) took place. By January 1, 1963, 700 individuals were recorded in the country.<ref name="s1380">{{Harvnb|Heptner|Sludskii|2002|pp=1380–1383}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Urban raccoons=== | ||

| + | [[File:Waschbaer auf dem Dach.jpg|thumb|On the roof of a house in Albertshausen, Germany]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Due to its adaptability, the raccoon has been able to use [[urban area]]s as a habitat. The first sightings were recorded in a [[suburb]] of [[Cincinnati]] in the 1920s. Since the 1950s, raccoons have been present in [[Washington, D.C.]], Chicago, and Toronto.<ref name="untersuchungen">{{cite journal|first=Frank-Uwe|last=Michler|title=Untersuchungen zur Raumnutzung des Waschbären (''Procyon lotor'', L. 1758) im urbanen Lebensraum am Beispiel der Stadt Kassel (Nordhessen)|pages=7|date=2003-06-25|url=http://www.projekt-waschbaer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Diplomarbeit-Waschbaer-Michler.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-12-07|language=German}} (Diploma thesis at the University of Halle-Wittenberg)</ref> Since the 1960s, [[Kassel]] has hosted Europe's first and densest population in a large urban area, with about 50 to 150 animals per square kilometer (130–400 animals per square mile), a figure comparable to those of urban habitats in North America.<ref name="untersuchungen" /><ref>Hohmann, p. 108</ref> Home range sizes of urban raccoons are only three to 40 hectares (7.5–100 acres) for females and eight to 80 hectares (20–200 acres) for males.<ref name="Stand der Wissenschaft">{{cite web|url=http://www.projekt-waschbaer.de/stand-der-wissenschaft/|title=Stand der Wissenschaft|accessdate=2008-12-07|last=Michler|first=Frank-Uwe|coauthors=Köhnemann, Berit A.|work=„Projekt Waschbär“|publisher=Gesellschaft für Wildökologie und Naturschutz e.V.|language=German}}</ref> In small towns and suburbs, many raccoons sleep in a nearby forest after foraging in the settlement area.<ref name="untersuchungen" /><ref>Bartussek, p. 20</ref> Fruit and insects in gardens and leftovers in municipal waste are easily available food sources.<ref>Bartussek, p. 21</ref> Furthermore, a large number of additional sleeping areas exist in these areas, such as hollows in old garden trees, cottages, garages, abandoned houses, and attics. The percentage of urban raccoons sleeping in abandoned or occupied houses varies from 15% in Washington, D.C. (1991) to 43% in Kassel (2003).<ref>Bartussek, p. 20; Hohmann, p. 108</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Health== | ||

| + | [[File:Baylisascaris larvae.jpg|left|thumb|''Baylisascaris procyonis'' larvae]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Raccoons can carry [[rabies]], a lethal disease caused by the [[neurotropic virus|neurotropic]] rabies [[virus]] carried in the [[saliva]] and transmitted by bites. Its spread began in Florida and [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]] in the 1950s and was facilitated by the introduction of infected individuals to [[Virginia]] and North Dakota in the late 1970s.<ref name="z113">Zeveloff, p. 113</ref> Of the 6,940 documented rabies cases reported in the United States in 2006, 2,615 (37.7%) were in raccoons.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Blanton|first=Jesse D.|coauthors=Hanlon, Cathleen A.; Rupprecht, Charles E.|date=2007-08-15|title=Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2006|journal=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|volume=231|issue=4|pages=540–556|publisher=American Veterinary Medical Association|location=Schaumburg, Illinois|issn=0003-1488|doi=10.2460/javma.231.4.540|pmid=17696853}}</ref> The [[United States Department of Agriculture|U.S. Department of Agriculture]], as well as local authorities in several U.S. states and Canadian provinces, has developed oral [[vaccination]] programs to fight the spread of the disease in endangered populations.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aphis.usda.gov/wildlife_damage/oral_rabies/index.shtml|title=National Rabies Management Program Overview|accessdate=2010-12-28|date=2009-09-25|work=Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service|publisher=United States Department of Agriculture}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://health.state.tn.us/FactSheets/raccoon.htm|title=Raccoons and Rabies|accessdate=2008-12-07|work=Official website of the State of Tennessee|publisher=Tennessee Department of Health}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mrnf.gouv.qc.ca/english/press/press-release-detail.jsp?id=7091|publisher=Gouvernement du Québec|title=Major operation related to raccoon rabies – Close to one million vaccinated baits will be spread in the Estrie and Montérégie regions from August 18 to 23, 2008|accessdate=2010-12-28|date=2008-08-18}}</ref> Only one human fatality has been reported after transmission of the rabies virus from a raccoon.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Silverstein|first=M. A.|coauthors=Salgado, C. D.; Bassin, S.; Bleck, T. P.; Lopes, M. B.; Farr, B. M.; Jenkins, S. R.; Sockwell, D. C.; Marr, J. S.; Miller, G. B.|date=2003-11-14|title=First Human Death Associated with Raccoon Rabies|journal=Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report|volume=52|issue=45|pages=1102–1103|publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|location=Atlanta, Georgia|url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5245a4.htm|accessdate=2008-12-07|pmid=14614408}}</ref> Among the main symptoms for rabies in raccoons are a generally sickly appearance, impaired mobility, abnormal vocalization, and [[aggression|aggressiveness]].<ref name="rabies">{{cite journal|last=Rosatte|first=Rick|coauthors=Sobey, Kirk; Donovan, Dennis; Bruce, Laura; Allan, Mike; Silver, Andrew; Bennett, Kim; Gibson, Mark; Simpson, Holly; Davies, Chris; Wandeler, Alex; Muldoon, Frances|date=1 July 2006| title=Behavior, Movements, and Demographics of Rabid Raccoons in Ontario, Canada: Management Implications|journal=Journal of Wildlife Diseases|volume=42|issue=3|pages=589–605|publisher=The Wildlife Disease Association|location=USA|issn=0090-3558|url=http://www.jwildlifedis.org/cgi/content/full/42/3/589|accessdate=2008-12-07|pmid=17092890}}</ref> There may be no visible signs at all, however, and most individuals do not show the aggressive behavior seen in infected canids; rabid raccoons will often retire to their dens instead.<ref name="stellungnahme" /><ref name=autogenerated1 /><ref name="rabies" /> Organizations like the [[United States Forest Service|U.S. Forest Service]] encourage people to stay away from animals with unusual behavior or appearance, and to notify the proper authorities, such as an [[animal control officer]] from the local [[health department]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.na.fs.fed.us/spfo/pubs/misc/raccoon/raccoon.htm|title=The Raccoon—Friend or Foe?|accessdate=2008-12-07|work=Northeastern Area State & Private Forestry – USDA Forest Service}}</ref><ref name="wdfw">{{cite web|url=http://wdfw.wa.gov/wlm/living/raccoons.htm|title=Raccoons|accessdate=2008-12-07|last=Link|first=Russell|work=Living with Wildlife|publisher=Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife| archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080324192751/http://wdfw.wa.gov/wlm/living/raccoons.htm| archivedate = March 24, 2008}}</ref> Since healthy animals, especially nursing mothers, will occasionally forage during the day, daylight activity is not a reliable indicator of illness in raccoons.<ref name="b10z99" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unlike rabies and at least a dozen other [[pathogen]]s carried by raccoons, [[Canine distemper|distemper]], an [[epizootic]] virus, does not affect humans.<ref>MacClintock, p. 72; Zeveloff, p. 114</ref> This disease is the most frequent natural cause of death in the North American raccoon population and affects individuals of all age groups.<ref name="ergebnisse" /> For example, 94 of 145 raccoons died during an [[outbreak]] in [[Clifton, Ohio]], in 1968.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 112</ref> It may occur along with a following inflammation of the brain ([[encephalitis]]), causing the animal to display rabies-like symptoms.<ref name="z113" /> In Germany, the first eight cases of distemper were reported in 2007.<ref name="ergebnisse" /> | ||

| − | + | Some of the most important [[bacteria]]l diseases which affect raccoons are [[leptospirosis]], [[listeriosis]], [[tetanus]], and [[tularemia]]. Although internal [[parasitism|parasites]] weaken their [[immune system]]s, well-fed individuals can carry a great many roundworms in their [[Gastrointestinal tract|digestive tract]]s without showing symptoms.<ref>MacClintock, pp. 73–74; Zeveloff, p. 114</ref> The larvae of the ''Baylisascaris procyonis'' roundworm, which can be contained in the feces and seldom causes a severe illness in humans, can be ingested when cleaning raccoon latrines without wearing breathing protection.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 169, 182</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Raccoons and people== | |

| + | ===Conflicts=== | ||

| + | [[File:Urban raccoon and skunk.JPG|thumb|A [[skunk]] and a raccoon share cat food morsels in a [[Hollywood]], [[California]], back yard]] | ||

| − | + | The increasing number of raccoons in urban areas has resulted in diverse reactions in humans, ranging from outrage at their presence to deliberate feeding.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 103–106</ref> Some wildlife experts and most public authorities caution against feeding wild animals because they might become increasingly obtrusive and dependent on humans as a food source.<ref>Bartussek, p. 34</ref> Other experts challenge such arguments and give advice on feeding raccoons and other wildlife in their books.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 117–121</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Harris|first=Stephen|coauthors=Baker, Phil|title=Urban Foxes|publisher=Whittet Books|location=Suffolk|year=2001|isbn=978-1873580516|pages=78–79}}</ref> Raccoons without a fear of humans are a concern to those who attribute this trait to rabies, but scientists point out this behavior is much more likely to be a behavioral adjustment to living in habitats with regular contact to humans for many generations.<ref>Bartussek, p. 24; Hohmann, p. 182</ref> Serious attacks on humans by groups of nonrabid raccoons are extremely rare and are almost always the result of the raccoon feeling threatened; at least one such attack has been documented.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/nationworld/2010003968_apusraccoonattack.html| title=Raccoons Maul Fla. Woman, 74, Who Shooed Them Away|accessdate=2010-12-28|date=2009-10-05|work=The Seattle Times}}</ref> Raccoons usually do not prey on domestic cats and dogs, but individual cases of killings have been reported.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.seattlepi.com/local/282218_racoons23.html|title=Raccoons rampaging Olympia|accessdate=2008-12-07|date=2006-08-23| work=seattlepi.com|publisher=Seattle Post-Intelligencer}}</ref> | |

| − | === | + | While overturned waste containers and raided fruit trees are just a nuisance to homeowners, it can cost several thousand dollars to repair damage caused by the use of attic space as dens.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Michler|first=Frank-Uwe|title=Untersuchungen zur Raumnutzung des Waschbären (''Procyon lotor, L. 1758) im urbanen Lebensraum am Beispiel der Stadt Kassel (Nordhessen)|pages=108|date=2003-06-25|url=http://www.projekt-waschbaer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Diplomarbeit-Waschbaer-Michler.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-12-07|language=German}} (Diploma thesis at the University of Halle-Wittenberg)</ref> Relocating or killing raccoons without a permit is forbidden in many urban areas on grounds of [[animal welfare]]. These methods usually only solve problems with particularly wild or aggressive individuals, since adequate dens are either known to several raccoons or will quickly be rediscovered.<ref name="wdfw" /><ref>Bartussek, p. 32; Hohmann, pp. 142–144, 169</ref> Loud noises, flashing lights and unpleasant odors have proven particularly effective in driving away a mother and her kits before they would normally leave the nesting place (when the kits are about eight weeks old).<ref name="wdfw" /><ref>Bartussek, p. 40</ref> Typically, though, only precautionary measures to restrict access to food waste and denning sites are effective in the long term.<ref name="wdfw" /><ref>Bartussek, pp. 36–40; Hohmann, p. 169</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Among all fruits and crops cultivated in agricultural areas, [[sweet corn]] in its milk stage is particularly popular among raccoons.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 87–88; MacClintock, p 49–50</ref> In a two-year study by [[Purdue University]] researchers, published in 2004, raccoons were responsible for 87% of the damage to corn plants.<ref>{{cite journal|last=MacGowan|first=Brian J.|coauthors=Humberg, Lee A.; Beasley, James C.; DeVault, Travis L.; Retamosa, Monica I.; Rhodes, Jr., Olin E.|title=Corn and Soybean Crop Depredation by Wildlife|pages=6|publisher=Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University|date=June 2006|url=http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/FNR/FNR-265-W.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-12-17}}</ref> Like other predators, raccoons searching for food can break into [[poultry]] houses to feed on chickens, ducks, their eggs, or feed.<ref name="wdfw" /><ref>Hohmann, p. 82; MacClintock, pp. 47–48</ref> Since they may enter tents and try to open locked containers on [[camping|camping grounds]], campers are advised to not keep food or toothpaste inside a tent.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/LAND/parks/specific/peninsula/camp/campcritters.html |title=WDNR – Peninsula Campground Animals |publisher=Dnr.state.wi.us |date=2009-05-29 |accessdate=2010-03-19}}</ref> | |

| − | + | Since raccoons are able to increase their rate of reproduction up to a certain limit,{{Vague|date=June 2010}} extensive hunting often does not solve problems with raccoon populations. Older males also claim larger home ranges than younger ones, resulting in a lower population density. The costs of large-scale measures to eradicate raccoons from a given area for a certain time are usually many times higher than the costs of the damage done by the raccoons.<ref name="stellungnahme" /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Mythology, arts, and entertainment=== | |

| + | [[File:S.E.C.C. hero twins 3 HRoe 2007.jpg|thumb|Stylized raccoon skin as depicted on the ''Raccoon Priests Gorget'' found at [[Spiro Mounds]]]] | ||

| − | + | {{See also|List of fictional raccoons}} | |

| − | + | In the [[mythology]] of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, the raccoon was the subject of [[folk tale]]s.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 25–46</ref> Stories such as "How raccoons catch so many [[crayfish]]" from the [[Tuscarora (tribe)|Tuscarora]] centered on its skills at foraging.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 41–43</ref> In other tales, the raccoon played the role of the [[trickster]] which outsmarts other animals, like coyotes and wolves.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 26–29, 38–40</ref> Among others, the [[Dakota Sioux]] believed the raccoon had natural [[spirit power]]s, since its mask resembled the facial paintings, two-fingered swashes of black and white, used during [[ritual]]s to connect to spirit beings.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 15–17</ref> The Aztecs linked supernatural abilities especially to females, whose commitment to their young was associated with the role of wise women in the tribal society.<ref>Holmgren, pp. 17–18</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The raccoon also appears in Native American art across a wide geographic range. [[Petroglyph]]s with engraved raccoon tracks were found in [[Lewis Canyon]], Texas; at the Crow Hollow petroglyph site in [[Grayson County, Kentucky]];<ref>Rock Art of Kentucky. Fred E. Coy, Thomas C. Fuller, Larry G. Meadows, James L. Swauger University Press of Kentucky, 2003 P60 & fig 65A</ref><ref>Pictographs, petroglyphs on rocks record beliefs of earliest Texans, http://www.austin360.com/recreation/content/recreation/stories/2008/12/1214rockart.html</ref> and in river drainages near [[Tularosa]], New Mexico and [[San Francisco]], California.<ref>Schaafsma, P. Indian Rock Art of the Southwest Albuq., U.NM, 1992</ref> A true-to-detail [[figurine]] made of [[quartz]], the ''Ohio Mound Builders' Stone Pipe'', was found near the [[Scioto River]]. The meaning and significance of the ''Raccoon Priests Gorget'', which features a stylized carving of a raccoon and was found at the [[Spiro Mounds]], Oklahoma, remains unknown.<ref name="spiro mounds">{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=TxYyscZlOXoC&pg=PA123 |title=The Arts of the North American ... – Google Bόcher |publisher=Books.google.de |date= 1986-09-25|accessdate=2010-03-19|isbn=9780933920569|author1=Wade, Edwin L}}</ref><ref>Holmgren, p. 45</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In Western culture, several [[autobiography|autobiographical]] [[novel]]s about living with a raccoon have been written, mostly for [[Children's literature|children]]. The best-known is [[Sterling North]]'s ''[[Rascal (book)|Rascal]]'', which recounts how he raised a kit during [[World War I]]. In recent years, [[anthropomorphism|anthropomorphic]] raccoons played main roles in the animated television series ''[[The Raccoons]]'', the computer-animated film ''[[Over the Hedge (film)|Over the Hedge]]'' and the video game series ''[[Sly Cooper (series)|Sly Cooper]]''. | |

| − | === | + | ===Hunting and fur trade=== |

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Lanpher Furs Auto Coat Raccoon S71.jpg|thumb|upright|Automobile coat made out of raccoon fur (1906, U.S.)]] |

| − | |||

| − | Raccoon | + | The fur of raccoons is used for clothing, especially for [[Raccoon coat|coats]] and [[coonskin cap]]s. At present, it is the material used for the inaccurately named "sealskin" cap worn by the [[Royal Fusiliers]] of [[Great Britain]].<ref>A Dictionary of Military Uniform: W.Y.Carman ISBN 0-684-15130-9</ref> Historically, [[Indigenous people of the Americas|Native American]] tribes not only used the fur for winter clothing, but also used the tails for ornament.<ref>Holmgren, p. 18</ref> Since the late 18th century, various types of [[scent hound]]s which are able to tree animals ("[[coonhound]]s") have been bred in the United States.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.akc.org/breeds/black_tan_coonhound/history.cfm|title=Black and Tan Coonhound History|accessdate=2008-12-11|work=American Kennel Club|publisher=American Kennel Club}}</ref> In the 19th century, when coonskins occasionally even served as means of payment, several thousand raccoons were killed each year in the United States.<ref>Holmgren, p. 74; Zeveloff, p. 160</ref> This number rose quickly when automobile coats became popular after the turn of the 20th century. In the 1920s, wearing a [[raccoon coat]] was regarded as [[status symbol]] among [[college student]]s.<ref>Holmgren, p. 77</ref> Attempts to breed raccoons in fur farms in the 1920s and 1930s in North America and Europe turned out not to be profitable, and farming was abandoned after prices for long-haired pelts dropped in the 1940s.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 161</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Schmidt|first=Fritz|title=Das Buch von den Pelztieren und Pelzen|year=1970|publisher=F. C. Mayer Verlag|location=Munich|language=German|pages=311–315}}</ref> Although raccoons had become rare in the 1930s, at least 388,000 were killed during the [[hunting season]] of 1934/35.<ref>Holmgren, p. 77; Zeveloff, pp. 75, 160, 173</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:Coonskin cap.JPG|left|thumb|upright|Coonskin cap]] | |

| − | === | + | After persistent population increases began in the 1940s, the seasonal hunt reached about one million animals in 1946/47 and two million in 1962/63.<ref>Zeveloff, pp. 75, 160</ref> The 1948 senatorial campaign of [[Estes Kefauver]], who wore such a cap for promotional purposes,<ref>Fontenay, Charles L. Estes Kefauver: A Biography. TN, 1980. rev by Salvatore LaGumina, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 462 (1982), p.180</ref> and the broadcast of three television episodes about the [[Frontier#American frontier|frontiersman]] [[Davy Crockett]] and the film ''[[Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier]]'' in 1954 and 1955 led to a high demand for [[coonskin cap]]s in the United States (though the caps supplied to the fad were typically made of [[faux fur]] with a raccoon tail attached).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://thecoonskincap.com/?page_id=2|title=History of the coonskin cap|accessdate=Nov 11, 2010}}</ref> Ironically, it is unlikely either Crockett or the actor who played him, [[Fess Parker]], actually wore a cap made from raccoon fur.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 170</ref> The seasonal hunt reached an all-time high with 5.2 million animals in 1976/77 and ranged between 3.2 and 4.7 million for most of the 1980s. In 1982, the average pelt price was $20.<ref>The Red Panda, Olingos, Coatis, Raccoons, and Their Relatives: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Procyonids and Ailurids By A. R. Glatston, IUCN/SSC Mustelid, Viverrid & Procyonid Specialist Group Edition: illustrated Published by IUCN, 1994, p. 9 ISBN 2-8317-0046-9, 9782831700465</ref> In the first half of the 1990s, the seasonal hunt dropped to 0.9 to 1.9 million due to decreasing pelt prices.<ref>Zeveloff, p. 160–161</ref> As of 1987, the raccoon was identified as the most important wild furbearer in North America in terms of revenue.<ref>The Red Panda, Olingos, Coatis, Raccoons, and Their Relatives: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Procyonids and Ailurids By A. R. Glatston, IUCN/SSC Mustelid, Viverrid & Procyonid Specialist Group Published by IUCN, 1994, p. 9</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | + | In many parts of the United States, raccoon [[hunting]] is still done at night with dogs, usually breeds of coonhounds. The dogs [[tracking (dog)|track]] the raccoon until it seeks refuge, usually in a tree, where it is either harvested or left for future hunts. Hunters can tell the progress of tracking by the type of bark emitted by the dogs; a unique bark indicates the raccoon has been "[[treeing|treed]]". | |

| − | The | + | ===As food=== |

| + | While primarily hunted for their fur, raccoons were also a source of food for Native Americans and Americans<ref>Holmgren, pp. 18–19, Zeveloff, p. 165</ref> and barbecued raccoon was a traditional food on American farms.<ref>Farm: A Year in the Life of an American Farmer. Richard Rhodes, reprint, U of Nebraska Press, 1997, p.270.</ref> It was often a festive meal. Raccoon was eaten by [[Slavery in the United States|American slaves]] at [[Christmas]],<ref>Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Digireads.com Publishing, 2005, p.72.</ref> but it was not necessarily a dish of the poor or rural; in San Francisco's ''[[The Golden Era]]'' of December 21, 1856, raccoon is among the specialties advertised for the holiday, and US President [[Calvin Coolidge]]'s pet raccoon Rebecca was originally sent to be served at the [[White House]] [[Thanksgiving dinner|Thanksgiving Dinner]].<ref>San Diego's Hilarious History By Herbert Lockwood, William Carroll Published by Coda Publications, 2004, p. 46.</ref><ref>Jen O'Neill. White House Life: Filling the Position of First Pet November 12, 2008. http://www.findingdulcinea.com/features/feature-articles/2008/november/Filling-the-Position-of-First-Pet.html.</ref> The first edition of ''[[The Joy of Cooking]]'', released in 1931, contained a recipe for preparing raccoon. | ||

| − | === | + | Because raccoons are generally thought of as endearing, cute, and/or [[varmints]], the idea of eating them is repulsive to mainstream consumers.<ref>{{cite news|last=Twohey |first=Megan |url=http://archives.chicagotribune.com/2008/jan/18/food/chi-raccoon_18_jan18 |title=Raccoon dinner: Who's game? Illinois, it turns out, has bountiful supply of the critters – and fans and foodies are gobbling them up – Chicago Tribune |publisher=Archives.chicagotribune.com |date=2008-01-18 |accessdate=2010-03-19}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Hill |first=Lee |url=http://www.mcclatchydc.com/251/story/59566.html |title=The other dark meat: Raccoon is making it to the table | McClatchy |publisher=Mcclatchydc.com |date=2009-01-13 |accessdate=2010-03-19}}</ref> However, many thousands of raccoons are still eaten each year in the United States.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://mdc.mo.gov/nathis/mammals/raccoon/ |title=Mammals: Raccoon – (Procyon lotor) |publisher=Mdc.mo.gov |accessdate=2010-03-19| archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080622145257/http://mdc.mo.gov/nathis/mammals/raccoon/| archivedate = June 22, 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ngpc.state.ne.us/wildlife/raccoon.asp|title=Raccoon|accessdate=2008-12-07|work=Nebraska Wildlife Species Guide|publisher=Nebraska Game and Parks Commission}}</ref> Although the [[Delafield, Wisconsin|Delafield (Wisconsin)]] Coon Feed has been an annual event since 1928, its culinary use is mainly identified with certain regions of the [[Southern United States|American South]] like [[Arkansas]] where the Gillett Coon Supper is an important political event.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/legacies/AR/200002687.html|title=Gillett Coon Supper|accessdate=2008-12-07|last=Berry|first=Marion|work=Local Legacies: Celebrating Community Roots|publisher=The Library of Congress|archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070809080640/http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/legacies/AR/200002687.html |archivedate = August 9, 2007|deadurl=yes}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gmtoday.com/news/local_stories/2008/Jan_08/01282008_02.asp |title=Coon Feed still packs ‘em in |publisher=Gmtoday.com |date=2008-01-28 |accessdate=2010-03-19}}</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===As pets=== | |

| + | [[File:Mm Gehege 02.jpg|right|thumb|Pen with climbing facilities, hiding places and a watering hole (on the lower left side)]] | ||

| + | As with most exotic pets, owning a raccoon often takes a significant amount of time and patience.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.filthylucre.com/raccoon-as-a-pet |title=Raccoon as a Pet |publisher=Filthylucre.com |accessdate=2010-08-02}}</ref> Raccoons may act unpredictably and aggressively and it can be quite difficult to teach them to obey and understand commands.<ref>Bartussek, p. 44; Hohmann, pp. 173–174</ref> In places where keeping raccoons as pets is not forbidden, such as in Wisconsin and other U.S. states, an [[exotic pet]] permit may be required.<ref>MacClintock, p. 129</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Bluett|first=Robert|coauthors=Craven, Scott|title=The Raccoon (''Procyon lotor'')|pages=2|publisher=Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System|year=1999|url=http://learningstore.uwex.edu/pdf/G3304.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-12-07}}</ref> | ||

| + | Sexually mature raccoons often show aggressive natural behaviors such as biting during the mating season.<ref>Bartussek, p. 44; Hohmann, pp. 185–186</ref> [[Neutering]] them at around five or six months of age decreases the chances of aggressive behavior developing.<ref>Hohmann, p. 186</ref> Raccoons can become [[obesity|obese]] and suffer from other disorders due to poor diet and lack of exercise.<ref>Hohmann, p. 185</ref> When fed with [[cat food]] over a long time period, raccoons can develop [[gout]].<ref>Hohmann, p. 180</ref> With respect to the research results regarding their social behavior, it is now required by law in Austria and Germany to keep at least two individuals to prevent loneliness.<ref name="gutachten">{{cite book|title=Gutachten über Mindestanforderungen an die Haltung von Säugetieren|url=http://www.lotor.de/download/haltung_saeugetiere.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2009-01-31|date=1996-06-10|publisher=Bundesministerium für Verbraucherschutz, Ernährung und Landwirtschaft|location=Bonn, Germany|language=German|pages=42–43}}</ref><ref name="mindestanforderungen">{{cite book|title=Mindestanforderungen an die Haltung von Säugetieren|url=http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2004_II_486/COO_2026_100_2_155421.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2010-08-21|date=2004-12-17|publisher=Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Frauen|language=German|page=23}}</ref> Raccoons are usually kept in a [[pen (enclosure)|pen]] (indoor or outdoor), also a legal requirement in Austria and Germany, rather than in the apartment where their natural [[curiosity]] may result in damage to property.<ref name="gutachten" /><ref name="mindestanforderungen" /><ref>Bartussek, p. 44; Hohmann, pp. 184, 187; MacClintock, p. 130–131</ref> | ||

| − | + | When orphaned, it is possible for kits to be [[wildlife rehabilitation|rehabilitated]] and [[Reintroduction|reintroduced]] to the wild. However, it is uncertain whether they readapt well to life in the wild.<ref>MacClintock, p. 130</ref> Feeding unweaned kits with [[cow's milk]] rather than a kitten replacement milk or a similar product can be dangerous to their health.<ref>Bartussek, p. 44; Hohmann, pp. 175–176</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | * [[Bandit (raccoon)]] | ||

| + | * [[Japanese Raccoon Dog]] | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | {{Reflist|colwidth=25em}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

| − | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * {{cite book|last=Bartussek|first=Ingo|title=Die Waschbären kommen|publisher=Cognitio|location=Niedenstein, Germany|language=German|year=2004|isbn=978-3932583100}} | ||

| + | *{{Cite book|last1=Heptner|first1=V. G.|last2=Sludskii|first2=A. A.|url=http://ia360707.us.archive.org/18/items/mammalsofsov212001gept/mammalsofsov212001gept.pdf|title=Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol. II, part 1b, Carnivores(Mustelidae & Procyonidae)|publisher=Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation|year=2002|isbn=90-04-08876-8|ref=harv|postscript=<!--None—>}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book|last=Hohmann|first=Ulf|coauthors=Bartussek, Ingo; Böer, Bernhard|title=Der Waschbär|publisher=Oertel+Spörer|location=Reutlingen, Germany|year=2001|language=German|isbn=978-3886273010}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book|last=Holmgren|first=Virginia C.|title=Raccoons in Folklore, History and Today's Backyards|publisher=Capra Press|location=Santa Barbara, California|year=1990|isbn=978-0884963127}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book|last=Lagoni-Hansen|first=Anke|title=Der Waschbär|publisher=Verlag Dieter Hoffmann|location=Mainz, Germany|year=1981|language=German|isbn=3-87341-037-0}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book|last=MacClintock|first=Dorcas|title=A Natural History of Raccoons|publisher=The Blackburn Press|location=Caldwell, New Jersey|year=1981|isbn=978-1930665675}} | ||