Urban planning

Urban planning is the integration of the disciplines of land-use planning and transport planning, to explore a wide range of aspects of the built and social environments of urbanized municipalities and communities. The focus is the design and regulation of the uses of space within the urban environment. This involves their physical structure, economic functions, and social impacts. In addition to the design of new cities or the expansion of existing ones, a key role of urban planning is urban renewal, and re-generation of inner cities by adapting urban-planning methods to existing cities suffering from long-term infrastructural decay.

Urban planning involves not just the science of designing efficient structures that support the lives of their inhabitants, but also involves the aesthetics of those structures. The environment deeply affects its inhabitants, and for human beings the impact is not simply physical and social, but also involves the emotional response to beauty or lack thereof. Thus, while ancient cities may have been built primarily for defense, the glorification of the ruler soon became a prominent feature through the construction of impressive buildings and monuments. Today, urban planners are aware of the needs of all citizens to have a pleasant environment, which supports their physical and mental health, in order for the city to be prosperous.

History

Urban planning as an organized profession has existed for less than a century. However, most settlements and cities reflect various degrees of forethought and conscious design in their layout and functioning.

The development of technology, particularly the discovery of agriculture, before the beginning of recorded history facilitated larger populations than the very small communities of the Paleolithic, and may have compelled the development of stronger governments at the same time. The pre-Classical and Classical ages saw a number of cities laid out according to fixed plans, though many tended to develop organically.

Designed cities were characteristic of the Mesopotamian, Harrapan, and Egyptian civilizations of the third millennium B.C.E..

Indus Valley Civilization

The cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley Civilization (in modern-day Pakistan and northwest India) are perhaps the earliest examples of deliberately planned and managed cities. The streets of these early cities were often paved and laid out at right angles in a grid pattern, with a hierarchy of streets from major boulevards to residential alleys. Archaeological evidence suggests that many Harrapan houses were laid out to protect from noise and enhance residential privacy; also, they often had their own water wells, probably for both sanitary and ritual purposes. These ancient cities were unique in that they often had drainage systems, seemingly tied to a well-developed ideal of urban sanitation.[1] Ur, located near the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in modern-day Iraq, also evidenced urban planning in later periods.

Mesopotamia

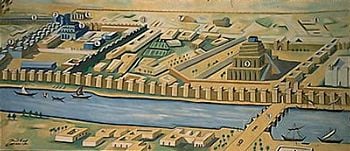

Babylon was a city-state of ancient Mesopotamia, the remains of which can be found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 55 miles south of Baghdad. All that remains today of the ancient famed city of Babylon is a mound, or tell, of broken mud-brick buildings and debris in the fertile Mesopotamian plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Iraq. It began as a small town that had sprung up by the beginning of the third millennium B.C.E.. The town flourished and attained prominence and political repute with the rise of the first Babylonian dynasty.

The city itself was built upon the Euphrates and divided in equal parts along its left and right banks, with steep embankments to contain the river's seasonal floods. Babylon grew in extent and grandeur over time, but gradually became subject to the rule of Assyria. It has been estimated that Babylon was the largest city in the world from c. 1770 to 1670 B.C.E., and again between c. 612 and 320 B.C.E. It was the "holy city" of Babylonia by approximately 2300 B.C.E., and the seat of the Neo-Babylonian Empire from 612 B.C.E. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Graeco-Roman period

The Greek Hippodamus (c. 407 B.C.E.) is widely considered the father of city planning in the West, for his design of Miletus. Alexander the Great commissioned him to lay out his new city of Alexandria, the grandest example of idealized urban planning of the Mediterranean world, where stability was aided in large part by its level site near a mouth of the Nile.

The ancient Romans used a consolidated scheme for city planning, developed for military defense, and civil convenience. The basic plan was a central forum with city services, surrounded by a compact rectilinear grid of streets and wrapped in a wall for defense. To reduce travel times, two diagonal streets cross the square grid corner-to-corner, passing through the central square. A river usually flowed through the city, to provide water, transportation, and sewage disposal.[2]

Many European towns, such as Turin, still preserve the essence of these schemes. The Romans had a very logical way of designing their cities. They laid out the streets at right angles, in the form of a square grid. All the roads were equal in width and length, except for two, which formed the center of the grid and intersected in the middle. One went East/West, the other North/South. They were slightly wider than the others. All roads were made of carefully fitted stones and smaller hard packed stones. Bridges were also constructed where needed. Each square marked by four roads was called an insula, which was the Roman equivalent of modern city blocks. Each insula was 80Â square yards (67Â mÂČ), with the land within each insula being divided for different purposes.

As the city developed, each insula would eventually be filled with buildings of various shapes and sizes and would be crisscrossed with back roads and alleys. Most insulae were given to the first settlers of a budding new Roman city, but each person had to pay for the construction of their own house. The city was surrounded by a wall to protect the city from invaders and other enemies, and to mark the city limits. Areas outside of the city limits were left open as farmland. At the end of each main road, there would be a large gateway with watchtowers. A portcullis covered the opening when the city was under siege, and additional watchtowers were constructed around the rest of the cityâs wall. A water aqueduct was built outside of the city's walls.

Middle Ages

The collapse of Roman civilization saw the end of their urban planning, among many other arts. Urban development in the Middle Ages, characteristically focused on a fortress, a fortified abbey, or a (sometimes abandoned) Roman nucleus, occurred "like the annular rings of a tree" whether in an extended village or the center of a larger city.[3] Since the new center was often on high, defensible ground, the city plan took on an organic character, following the irregularities of elevation contours like the shapes that result from agricultural terracing.

The ideal of wide streets and orderly cities was not lost, however. A few medieval cities were admired for their wide thoroughfares and other orderly arrangements. Todi in Italy has been called "the world's most livable city."[4] It is a place where man and nature, history and tradition come together to create a site of excellence. Todi had ancient Italic origins, but after the twelfth century C.E. the city expanded: The government was held first by consuls, and then by podestĂ and a people's captain, some of whom achieved wide fame. In 1244, the new quarters, housing mainly the new artisan classes, were enclosed in a new circle of walls. In 1290, the city had 40,000 inhabitants.

Other Italian examples of ideal cities planned according to scientific methods include Urbino(origins, fifteenth century), Pienza (1462), Ferrara (early twelfth century), San Giovanni Valdarno (early twelfth century), and San Lorenzo Nuovo (early twelfth century).

The juridical chaos of medieval cities (where the administration of streets was sometimes hereditary with various noble families), and the characteristic tenacity of medieval Europeans in legal matters, generally prevented frequent or large-scale urban planning. It was not until the Renaissance and the enormous strengthening of all central governments, from city-states to the kings of France, characteristic of that epoch could urban planning advance.

The Renaissance

The star-shaped fortification had a formative influence on the patterning of the Renaissance ideal city. This was employed by Michelangelo in the defensive earthworks of Florence. This model was widely imitated, reflecting the enormous cultural power of Florence in this age: "The Renaissance was hypnotized by one city type which for a century and a halfâfrom Filarete to Scamozziâwas impressed upon all utopian schemes: this is the star-shaped city."[3] Radial streets extend outward from a defined center of military, communal, or spiritual power. Only in ideal cities did a centrally planned structure stand at the heart, as in Raphael's Sposalizio of 1504.

The unique example of a rationally-planned quattrocento new city center, that of Vigevano, 1493-1495, resembles a closed space instead, surrounded by arcading. Filarete's ideal city, building on hints in Leone Battista Alberti's De re aedificatoria, was named "Sforzinda" in compliment to his patron; its 12-pointed shape, circumscribable by a "perfect" Pythagorean figure, the circle, takes no heed of its undulating terrain. The design of cities following the Renaissance was generally more to glorify the city or its ruler than to improve the lifestyle of its citizens.

Such ideas were taken up to some extent in North America. For example, Pierre L'Enfant's 1790 plan for Washington, D.C. incorporated broad avenues and major streets that radiated out from traffic circles, providing vistas toward important landmarks and monuments. All the original colonies had avenues named for them, with the most prominent states receiving more prestigious locations. In New England, cities such as Boston developed around a centrally located public space.

The grid plan also revived in popularity with the start of the Renaissance in Northern Europe. The baroque capital city of Malta, Valletta, dating back to the sixteenth century, was built following a rigid grid plan of uniformly designed houses, dotted with palaces, churches, and squares. In 1606, the newly founded city of Mannheim in Germany was laid out on the grid plan. Later came the New Town in Edinburgh and almost the entire city center of Glasgow, and many new towns and cities in Australia, Canada, and the United States. Arguably the most famous grid plan in history is the plan for New York City formulated in the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, a visionary proposal by the state legislature of New York for the development of most of upper Manhattan. William Penn's plan for Philadelphia was based on a grid plan, with the idea that houses and businesses would be spread out and surrounded by gardens and orchards, with the result more like an English rural town than a city. Penn advertised this orderly design as a safeguard against overcrowding, fire, and disease, which plagued European cities. Instead, the inhabitants crowded by the Delaware River and subdivided and resold their lots. The grid plan however, was taken by the pioneers as they established new towns on their travels westward. Although it did not take into account the topography of each new location, it facilitated the selling of parcels of land divided into standard-sized lots.

Asia

The Forbidden City was the Chinese imperial palace from the Ming Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty. It is located in the middle of Beijing, China, and now houses the Palace Museum. Built from 1406 to 1420, it served as the home of the Emperor and his household, as well as the ceremonial and political center of Chinese government for almost five centuries. The palace complex exemplifies traditional Chinese palatial architecture, and influenced cultural and architectural developments in East Asia and elsewhere.

It was designed to be the center of the ancient, walled city of Beijing. It is enclosed in a larger, walled area called the Imperial City. The Imperial City is, in turn, enclosed by the Inner City; to its south lies the Outer City. The Forbidden City remains important in the civic scheme of Beijing. The central north-south axis remains the central axis of Beijing. This axis extends to the south through Tiananmen gate to Tiananmen Square, the ceremonial center of the People's Republic of China. To the north, it extends through the Bell and Drum Towers to Yongdingmen. This axis is not exactly aligned north-south, but is tilted by slightly more than two degrees. Researchers now believe that the axis was designed in the Yuan Dynasty to be aligned with Xanadu, the other capital of their empire.

Central and South America

Many cities in Central American civilizations also engineered urban planning in their cities including sewage systems and running water. In Mexico, Tenochtitlan was the capital of the Aztec empire, built on an island in Lake Texcoco in what is now the Federal District in central Mexico. At its height, Tenochtitlan was one of the largest cities in the world, with close to 250,000 inhabitants.

Built around 1460, Machu Picchu is a pre-Columbian Inca site located 8,000 feet above sea on a mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley in Peru. Often referred to as "The Lost City of the Incas," Machu Picchu is one of the most familiar symbols of the Inca Empire. Machu Picchu is composed of 140 structures or features, including temples, sanctuaries, parks, and residences that include houses with thatched roofs. There are more than 100 flights of stone stepsâoften completely carved from a single block of graniteâand a great number of water fountains that are interconnected by channels and water-drains perforated in the rock that were designed for the original irrigation system. Evidence has been found to suggest that the irrigation system was used to carry water from a holy spring to each of the houses in turn. According to archaeologists, the urban sector of Machu Picchu was divided into three great districts: the Sacred District, the Popular District to the south, and the District of the Priests and the Nobility.

Developed nations

Modernism

In the developed countries of (Western Europe, North America, Japan, and Australasia), planning and architecture can be said to have gone through various stages of general consensus. First, there was the industrialized city of the nineteenth century, where control of building was largely held by businesses and the wealthy elite. Around 1900, there began to be a movement for providing citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments. The concept of garden cities, an approach to urban planning founded by Sir Ebenezer Howard led to the building of several model towns, such as Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City, the world's first garden cities, in Hertfordshire, Great Britain. However, these were principally small scale in size, typically dealing with only a few-thousand residents.[5]

It was not until the 1920s that Modernism began to surface. Based on the ideas of Le Corbusier and utilizing new skyscraper-building techniques, the Modernist city stood for the elimination of disorder, congestion, and the small scale, replacing them instead with pre-planned and widely spaced freeways and tower blocks set within gardens. There were plans for large-scale rebuilding of cities, such as the Plan Voisin, which proposed clearing and rebuilding most of central Paris. No large-scale plans were implemented until after World War II however.

The Athens Charter was the result of the 1933 CongrĂšs International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). The proceedings went unpublished until 1942, when Le Corbusier published them in heavily edited form. Both the conference and the resulting document concentrated on "The Functional City." As later documented by Le Corbusier, CIAM IV laid out a 95-point program for planning and construction of rational cities, addressing topics such as high-rise residential blocks, strict zoning, the separation of residential areas and transportation arteries, and the preservation of historic districts and buildings. The key underlying concept was the creation of independent zones for the four "functions": living, working, recreation, and circulation.

These concepts were widely adopted by urban planners in their efforts to rebuild European cities following World War II, for instance Mart Stam's plans for postwar Dresden. Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, housing shortages caused by war destruction led many cities around the world to build substantial amounts of government-subsidized housing blocks. Planners at the time used the opportunity to implement the Modernist ideal of towers surrounded by gardens. [Brasilia]], a fine example of the application of the Athens charter, followed it virtually to the letter.

Constructed between 1956 and 1960, BrasĂlia is the capital of Brazil. The city and its district are located in the Central-West region of the country, along a plateau known as Planalto Central. It has a population of about 2,557,000 as of the 2008 IBGE estimate, making it the fourth largest city in Brazil. It is the only twentieth-century city listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The city was planned and developed in 1956 with LĂșcio Costa as the principal urban planner and Oscar Niemeyer as the principal architect. In 1960, it formally became Brazil's national capital. The locating of residential buildings around expansive urban areas, of building the city around large avenues, and dividing it into sectors, has sparked a debate and reflection on life in big cities in the twentieth century. The city's planned design included specific areas for almost everything, including accommodationâHotel Sectors North and South. However, new areas are now being developed as locations for hotels, such as the Hotels and Tourism Sector North, located on the shores of Lake ParanoĂĄ. When seen from above, the main planned part of the city's shape resembles an airplane or a butterfly.

Post-Modernism

However, the Athens Charter was roundly criticized within the profession for its inflexible approach and its inhumane results. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, many planners were coming to realize that the imposition of Modernist clean lines and a lack of human scale also tended to sap vitality from the community. This was expressed in high crime and social problems within many of these planned neighborhoods.[6] Modernism can be said to have ended in the 1970s when the construction of the cheap, uniform tower blocks ended in many countries, such as Britain and France. Since then many have been demolished and in their way more conventional housing has been built. Rather than attempting to eliminate all disorder, planning now concentrates on individualism and diversity in society and the economy. This is the Post-Modernist era.[6] [7]

Las Vegas, Nevada is one American city that has emerged along Post-Modernist lines in that it is specifically designed to create a unique experience, often simulated, for its millions of annual visitors who come from a wide diversity of nations, ethnic backgrounds, and socio-economic classes.[8]

Aspects of planning

In developed countries, there has been a backlash against excessive man-made clutter in the visual environment, such as signposts, signs, and hoardings.[9] Other issues that generate strong debate among urban designers are tensions between peripheral growth, increased housing density, and planned new settlements. There are also unending debates about the benefits of mixing tenures and land uses, versus the benefits of distinguishing geographic zones where different uses predominate. Regardless, all successful urban planning considers urban character, local identity, respect for heritage, pedestrians, traffic, utilities, and natural hazards.

Aesthetics

Planners are important in managing the growth of cities, applying tools like zoning to manage the uses of land, and growth management to manage the pace of development. When examined historically, many of the cities now thought to be most beautiful are the result of dense, long-lasting systems of prohibitions and guidance about building sizes, uses, and features. These allowed substantial freedoms, yet enforced styles, safety, and materials in practical ways. Many conventional planning techniques are being repackaged using the contemporary term smart growth.

Safety

Historically within the Middle East, Europe, and the rest of the Old World, settlements were located on higher ground (for defense) and close to fresh-water sources. Cities have often grown onto coastal and flood plains at risk of floods and storm surges. If the dangers can be localized, then the affected regions can be made into parkland or Greenbelt, often with the added benefit of an open-space provision.

Extreme weather, flooding, or other emergencies can often be greatly mitigated with secure emergency-evacuation routes and emergency-operations centers. These are relatively inexpensive and unintrusive, and many consider them a reasonable precaution for any urban space. Many cities also have planned, built safety features, such as levees, retaining walls, and shelters.

City planning tries to control criminality with structures designed from theories such as socio-architecture or environmental determinism. These theories say that an urban environment can influence individuals' obedience to social rules. The theories often say that psychological pressure develops in more densely developed, unadorned areas. This stress causes some crimes and some use of illegal drugs. The antidote is usually more individual space and better, more beautiful design in place of functionalism.

Oscar Newmanâs defensible space theory cites the Modernist housing projects of the 1960s as an example of environmental determinism, where large blocks of flats are surrounded by shared and disassociated public areas, which are hard for residents to identify with. As those on lower incomes cannot hire others to maintain public space such as security guards or grounds keepers, and because no individual feels personally responsible, there was a general deterioration of public space leading to a sense of alienation and social disorder.

Slums

The rapid urbanization of the twentieth century resulted in a significant amount of slum habitation in the major cities of the world, particularly in developing countries. There is significant demand for planning resources and strategies to address the issues that arise from slum development.[10]

The issue of slum habitation has often been resolved via a simple policy of clearance. However, there are more creative solutions such as Nairobi's "Camp of Fire" program, where established slum-dwellers have promised to build proper houses, schools, and community centers without any government money, in return for land they have been illegally squatting on for 30 years. The "Camp of Fire" program is one of many similar projects initiated by Slum Dwellers International, which has programs in Africa, Asia, and South America.[11]

Urban decay

Urban decay is a process by which a city, or a part of a city, falls into a state of disrepair and neglect. It is characterized by depopulation, economic restructuring, property abandonment, high unemployment, fragmented families, political disenfranchisement, crime, and desolate urban landscapes.

During the 1970s and 1980s, urban decay was often associated with central areas of cities in North America and parts of Europe. During this time period, major changes in global economies, demographics, transportation, and government policies created conditions that fostered urban decay.[12] Many planners spoke of "white flight" during this time. This pattern was different than the pattern of "outlying slums" and "suburban ghettos" found in many cities outside of North America and Western Europe, where central urban areas actually had higher real-estate vales. Starting in the 1990s, many of the central urban areas in North America experienced a reversal of the urban decay of previous decades, with rising real-estate values, smarter development, demolition of obsolete social-housing areas, and a wider variety of housing choices.[13]

Reconstruction and renewal

Areas devastated by war or invasion represent a unique challenge to urban planners. Buildings, roads, services, and basic infrastructure, like power, water, and sewerage, are often severely compromised and need to be evaluated to determine what can be salvaged for re-incorporation. There is also the problem of the existing population, and what needs they may have. Historic, religious, or social centers also need to be preserved and re-integrated into the new city plan. A prime example of this is the capital city of Kabul, Afghanistan, which, after decades of civil war and occupation, has regions that have literally been reduced to rubble and desolation. Despite this, the indigenous population continues to live in the area, constructing makeshift homes and shops out of whatever can be salvaged. Any reconstruction plan proposed, such as Hisham Ashkouri's City of Light Development, needs to be sensitive to the needs of this community and its existing culture, businesses, and so forth.

Transport

Transport within urbanized areas presents unique problems. The density of an urban environment can create significant levels of road traffic, which can impact businesses and increase pollution. Parking space is another concern, requiring the construction of large parking garages in high-density areas which could be better used for other development.

Good planning uses transit oriented development, which attempts to place higher densities of jobs or residents near high-volume transportation. For example, some cities permit only commercial and multi-story apartment buildings within one block of train stations and multilane boulevards, while single-family dwellings and parks are located farther away.

Suburbanization

In some countries, declining satisfaction with the urban environment is held to blame for continuing migration to smaller towns and rural areas (so-called urban exodus). Successful urban planning supported Regional planning can bring benefits to a much larger hinterland or city region and help to reduce both congestion along transport routes and the wastage of energy implied by excessive commuting.

Environmental factors

Environmental protection and conservation are of utmost importance to many planning systems across the world. Not only are the specific effects of development to be mitigated, but attempts are made to minimize the overall effect of development on the local and global environment. This is commonly done through the assessment of Sustainable urban infrastructure. In Europe this process is known as Sustainability Appraisal.

In most advanced urban- or village-planning models, local context is critical. Gardening and other outdoor activities assume a central role in the daily life of many citizens. Environmental planners are focusing on smaller systems of resource extraction, energy production, and waste disposal. There is even a practice known as Arcology, which seeks to unify the fields of ecology and architecture, using principles of landscape architecture to achieve a harmonious environment for all living things. On a small scale, the eco-village theory has become popular, as it emphasizes a traditional, 100-to-140-person scale for communities.

Light and sound

The urban canyon effect is a colloquial, non-scientific term referring to street space bordered by very high buildings. This type of environment may shade the sidewalk level from direct sunlight during most daylight hours. While an often-decried phenomenon, it is rare except in very dense, hyper-tall urban environments, such as those found in Lower and Midtown Manhattan, Chicago's Loop, and Kowloon in Hong Kong.

In urban planning, sound is usually measured as a source of pollution. Another perspective on urban sounds is developed in Soundscape studies emphasizing that sound aesthetics involves more than noise abatement and decibel measurements.

Sustainable development and sustainability

Sustainable development and sustainability have become important concepts in urban planning, with the recognition that current consumption and living habits may be leading to problems such as the overuse of natural resources, ecosystem destruction, urban heat islands, pollution, growing social inequality, and large-scale climate change. Many urban planners have, as a result, begun to advocate for the development of sustainable cities.[14] However, the notion of sustainable development is somewhat controversial. Wheeler suggested a definition for sustainable urban development to be as "development that improves the long-term social and ecological health of cities and towns." He went on to suggest a framework that might help all to better understand what a "sustainable" city might look like. These include compact, efficient land use; less automobile use yet with better access; efficient resource use, less pollution and waste; the restoration of natural systems; good housing and living environments; a healthy social ecology; sustainable economics; community participation and involvement; and preservation of local culture and wisdom.[14]

Evolution of urban planning

An understanding of the evolution of the purpose of cities is needed to explain how urban planning has developed over the years. Originally, urban living was established as a defense against invaders and an efficient way to circulate foodstuffs and essential materials to an immediate population. Later, as production methods developed and transportation modes improved, cities, often serving as governmental centers, became good locations for industry, with finished goods being distributed both locally and to surrounding areas. Still later, cities became valued for their cultural attractions to residents and visitors alike. Today, people may just as well prefer to live in cities with well-planned neighborhoods as they would the suburbs.

The traditional planning process focused on top-down processes where the urban planner created the plans. The planner is usually skilled in either surveying, engineering, or architecture, bringing to the town-planning process ideals based around these disciplines. They typically worked for national or local governments. Changes to the planning process over past decades have witnessed the metamorphosis of the role of the urban planner in the planning process. The general objectives of strategic urban planning (SUP) include clarifying which city model is desired and working towards that goal, coordinating public and private efforts, channeling energy, adapting to new circumstances, and improving the living conditions of the citizens affected. Community organizers and social workers are now very involved in planning from the grassroots level.[15] Developers too have played roles in influencing the way development occurs, particularly through project-based planning. Many developments were the result of large- and small-scale developers who purchased land, designed the district, and constructed the development from scratch.

Recent theories of urban planning, espoused for example by mathematician and polymath Salingaros, see the city as a adaptive system that grows according to process similar to those of plants.[16] [17] They suggest that urban planning should take its cues from such natural processes.

Notes

- â Jacob Eapen 1997, Indus River Valley Civilization. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- â Vitrivius and Morris H. Morgan (trans.), 1914, The Ten Books on Architecture, Bk I, (Dover, 1914. ISBN 9780486206455.)

- â 3.0 3.1 Siegfried Giedion, Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition (Boston, MA: Harvard University Press; 5 Rev Enl edition, 2008, ISBN 9780674030473)

- â âTodi Come una Citta` Sostenibile,â keynote, Inauguration Convocation Academic Year Universita` della Terza Eta, October 1992, Todi, Italy; "Todi Citta del Futuro," and "Come Todi Puo Divenire Citta Ideale e Modello per il Futuro," in ll Sole Venti Quattro Ore, Milano, Italy, November 28, 1991.

- â Peter Geoffrey Hall, and Colin Ward, Sociable Cities: The Legacy of Ebenezer Howard (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1998, ISBN 047198504X).

- â 6.0 6.1 Eleanor Smith Morris, British Planning and Urban Design: Principles and Policies (Addison Wesley Publishing Company, 1998, ISBN 0582234964).

- â Koray Velibeyoglu, Urban Design in the Postmodern Context, Izmir Institute of Technology, 1999. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- â Las Vegas: Postmodern City of Casinos and Simulation, Transparency Now. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- â Bernard Orsman, Tensions spill over in billboard row, The New Zealand Herald, March 16, 2007. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- â Commonwealth Association of Planners, Reinventing planning: A new governance paradigm for managing Human settlements, World Planners Congress, Vancouver 17-20 June 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- â Meera Selva, Kenyans buy into slum plan, The Christian Science Monitor, May 26, 2004. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- â Hans Skifter Andersen, Urban Sores: On the Interaction Between Segregation, Urban Decay, and Deprived Neighbourhoods (Ashgate Publishing, 2003, ISBN 0754633055)

- â Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (Oxford University Press, 1987, ISBN 0195049837)

- â 14.0 14.1 Stephen Wheeler, Planning Sustainable and Livable Cities (New York, NY: Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0415271738)

- â John Forester, Planning in the Face of Conflict (New York, NY: Routledge, 1987, ISBN 0415271738)

- â Nikos A. Salingaros, Principles of Urban Structure (Tecne Press, 2005, ISBN 908594001X).

- â Nikos A. Salingaros, Fractals in the New Architecture, Archimagazine, 2001. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andersen, Hans Skifter. Urban Sores: On the Interaction Between Segregation, Urban Decay, and Deprived Neighbourhoods. Ashgate Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0754633055

- Forester, John. Planning in the Face of Conflict. New York, NY: Routledge, 1987. ISBN 0415271738

- Garvin, Alexander. The American City: What Works and What Doesn't. New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 2002. ISBN 0071373675

- Giedion, Siegfried. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 5th edition, 2008. ISBN 9780674030473

- Grogan, Paul, and Proscio, Tony. Comeback Cities: A Blueprint for Urban Neighborhood Revival, 2000. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2000. ISBN 9780813368139

- Hall, Peter Geoffrey, and Colin Ward. Sociable Cities: The Legacy of Ebenezer Howard. John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1998. ISBN 047198504X

- Hopkins, Lewis D. Urban Development: The Logic Of Making Plans. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2001. ISBN 1559638532

- Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0195049837

- Monti, Daniel J. The American City: A Social and Cultural History. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1999. ISBN 9781557869180

- Morris, Eleanor Smith. British Planning and Urban Design: Principles and Policies. Addison Wesley Publishing Company, 1998. ISBN 0582234964

- Salingaros, Nikos A. Principles of Urban Structure. Tecne Press, 2005. ISBN 908594001X

- Santamouris, Matheos. Environmental Design of Urban Buildings: An Integrated Approach. London: Earthscan, 2004. ISBN 9781902916422

- Tunnard, Christopher, and Pushkarev, Boris. Man-Made America: Chaos or Control?: An Inquiry into Selected Problems of Design in the Urbanized Landscape. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974. OCLC 67264178

- Vitrivius. The Ten Books on Architecture, Bk I. Dover, 1914. ISBN 9780486206455

- Wheeler, Stephen. Planning Sustainable and Livable Cities. New York, NY: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0415271738

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.