Xenon

- For other uses, see Xenon (disambiguation).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, Symbol, Number | xenon, Xe, 54 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical series | noble gases | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, Period, Block | 18, 5, p | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | colorless

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic mass | 131.293(6) g/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Kr] 4d10 5s2 5p6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 18, 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | gas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density | (0 °C, 101.325 kPa) 5.894 g/L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 161.4 K (-111.7 °C, -169.1 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 165.03 K (-108.12 °C, -162.62 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 289.77 K, 5.841 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.27 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 12.64 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat capacity | (25 °C) 20.786 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | cubic face centered | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 0, +1, +2, +4, +6, +8 (rarely more than 0) (weakly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | 2.6 (Pauling scale) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | 1st: 1170.4 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd: 2046.4 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd: 3099.4 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius (calc.) | 108 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 130 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 216 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | nonmagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | (300 K) 5.65 mW/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | (liquid) 1090 m/s | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS registry number | 7440-63-3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable isotopes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Xenon (chemical symbol Xe, atomic number 54) is a colorless, odorless, heavy noble gas. It occurs in the Earth's atmosphere in trace amounts and was part of the first noble gas compound synthesized.[1] [2]

Occurrence and extraction

Xenon is a trace gas in the Earth's atmosphere, occurring in one part in twenty million. In addition, it is found in gases emitted from some mineral springs.

This element can be extracted by fractional distillation of liquid air or by selective adsorption (surface binding) on activated carbon. The isotopes Xe-133 and Xe-135 are synthesized by neutron irradiation within air-cooled nuclear reactors.

History

Xenon (from the Greek word ξένος, meaning "strange") was discovered in England by William Ramsay and Morris Travers on July 12, 1898, shortly after they had discovered the elements krypton and neon. They found it in the residue left over from evaporating components of liquid air.

Notable characteristics

Xenon is a member of the noble gas series in the periodic table. It is situated between krypton and radon in group 18 (former group 8A), and is placed after iodine in period 5.

As the noble gases are chemically very inert, they are said to have a chemical valence of zero. Nonetheless, the term "inert" is not an entirely accurate description of this group of elements, because some of them—including xenon—have been shown to form compounds.

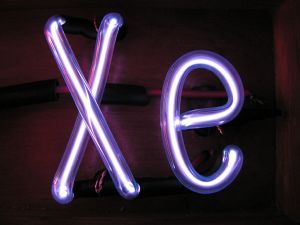

In a gas-filled tube, xenon emits a blue glow when the gas is excited by electrical discharge. Using tens of gigapascals of pressure, xenon has been forced into a metallic phase.[3] Xenon can also form "clathrates" (cage-like molecules) with water, when xenon atoms are trapped in a lattice of water molecules.

Isotopes

Naturally occurring xenon is made of seven stable and two slightly radioactive isotopes. Beyond these stable forms, there are 20 unstable isotopes that have been studied. Xe-129 is produced by beta decay of I-129 (half-life: 16 million years); Xe-131m, Xe-133, Xe-133m, and Xe-135 are some of the fission products of both U-235 and Pu-239, and therefore used as indicators of nuclear explosions.

The artificial isotope Xe-135 is of considerable significance in the operation of nuclear fission reactors. Xe-135 has a huge cross section for thermal neutrons, 2.65x106 barns, so it acts as a neutron absorber or "poison" that can slow or stop the chain reaction after a period of operation. This was discovered in the earliest nuclear reactors built by the American Manhattan Project for plutonium production. Fortunately the designers had made provisions in the design to increase the reactor's reactivity (the number of neutrons per fission that go on to fission other atoms of nuclear fuel).

Relatively high concentrations of radioactive xenon isotopes are also found emanating from nuclear reactors due to the release of this fission gas from cracked fuel rods or fissioning of uranium in cooling water. The concentrations of these isotopes are still usually low compared to naturally occurring radioactive noble gases such as Rn-222.

Because xenon is a tracer for two parent isotopes, Xe isotope ratios in meteorites are a powerful tool for studying the formation of the solar system. The I-Xe method of dating gives the time elapsed between nucleosynthesis and the condensation of a solid object from the solar nebula. Xenon isotopes are also a powerful tool for understanding terrestrial differentiation. Excess Xe-129 found in carbon dioxide well gases from New Mexico was believed to be from the decay of mantle-derived gases soon after Earth's formation.[4]

Compounds

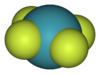

Xenon and the other noble gases had long been considered completely chemically inert and unable to form compounds. In 1962, however, at the University of British Columbia, the first xenon compound—xenon hexafluoroplatinate—was synthesized. Now, many compounds of xenon are known, including xenon difluoride, xenon tetrafluoride, xenon hexafluoride, xenon tetroxide, xenon hydrate, xenon deuterate, and sodium perxenate. A highly explosive compound, xenon trioxide, has also been made. There are at least 80 xenon compounds in which fluorine or oxygen is bonded to xenon. Some compounds of xenon are colored, but most are colorless.

Recently, researchers (M. Räsänen at al.) at the University of Helsinki in Finland made xenon dihydride (HXeH), xenon hydride-hydroxide (HXeOH), and hydroxenoacetylene (HXeCCH). These compounds are stable up to 40K.[5]

Applications

This gas is most widely and most famously used in light-emitting devices called Xenon flash lamps, which are used in photographic flashes, stroboscopic lamps, to excite the active medium in lasers which then generate coherent light, in bactericidal lamps (rarely), and in certain dermatological uses. Continuous, short-arc, high pressure Xenon arc lamps have a color temperature closely approximating noon sunlight and are used in solar simulators, some projection systems, automotive HID headlights and other specialized uses. They are an excellent source of short wavelength ultraviolet light and they have intense emissions in the near infrared, which are used in some night vision systems.

Other uses of Xenon:

- It has been used as a general anaesthetic, though the cost is prohibitive.

- In nuclear energy applications it is used in bubble chambers, probes, and in other areas where a high molecular weight and inert nature is a desirable quality.

- Perxenates are used as oxidizing agents in analytical chemistry.

- The isotope Xe-133 is useful as a radioisotope.

- Hyperpolarized MRI of the lungs and other tissues using 129Xe.[6]

- Preferred fuel for Ion propulsion because of high molecular weight, ease of ionization, store as a liquid at near room temperature (but at high pressure) yet easily converts back into a gas to fuel the engine, inert nature makes it environmentally friendly and less corrosive to an ion engine than other fuels such as mercury or cesium. Europe's SMART-1 spacecraft utilized Xenon in its engines. [7]

- Is commonly used in protein crystallography. Applied at high pressure (~600 psi) to a protein crystal, xenon atoms bind in predominantly hydrophobic cavities, often creating a high quality, isomorphous, heavy-atom derivative.

Precautions

The gas can be safely kept in normal sealed glass containers at standard temperature and pressure. Xenon is non-toxic, but many of its compounds are toxic due to their strong oxidative properties.

Because xenon is denser than air, the speed of sound in xenon is slower than that in air, and when inhaled, lowers the resonant frequencies of the vocal tract. This produces a characteristic lowered voice pitch, opposite the high-pitched voice caused by inhalation of helium. Like helium, xenon does not satisfy the body's need for oxygen and is a simple asphyxiant; consequently, many universities no longer allow the voice stunt as a general chemistry demonstration. As xenon is expensive, the gas sulfur hexafluoride, which is similar to xenon in molecular weight (146 vs 131), is generally used in this stunt, although it too is an asphyxiant.

A myth exists that xenon is too heavy for the lungs to expel unassisted, and that after inhaling xenon, it is necessary to bend over completely at the waist to allow the excess gas to "spill" out of the body. In fact, the lungs mix gases very effectively and rapidly, such that xenon would be purged from the lungs within a breath or two. There is a danger associated with any heavy gas in large quantities: it may sit invisibly in a container, and if a person enters a container filled with an odorless, colorless gas, they may find themselves breathing it unknowingly. Xenon is rarely used in large enough quantities for this to be a concern, though the potential for danger exists any time a tank or container of xenon is kept in an unventilated space.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Los Alamos National Laboratory – Xenon

- ↑ Thermophysical properties of neon, argon, krypton, and xenon / V. A. Rabinovich ... Theodore B. Selover, English-language edition ed, Washington [u.a.] Hemisphere Publ. Corp. [u.a.] , 1988. - XVIII (National standard reference data service of the USSR, You can now find Xenon at $60.00 per .077 pps

- ↑ Caldwell, W. A. and Nguyen, J., Pfrommer, B., Louie, S., and Jeanloz, R. (1997). Structure, bonding and geochemistry of xenon at high pressures. Science 277: 930-933.

- ↑ Boulos, M.S. and Manuel, O.K. (1971). The xenon record of extinct radioactivities in the Earth.. Science 174: 1334-1336.

- ↑ See [1] in its paragraph starting "Many recent findings".

- ↑ Use of Xe in MRI

- ↑ [CNN Article regardint SMART-1 and Xenon

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.