Stele

- This article is about the stone structure. For the usage in plant biology, see stele (biology).

A stele (from Greek: στήλη, stēlē, IPA: [ˈstili]; plural: stelae, στῆλαι, stēlai, IPA: [ˈstilaɪ]; also found: Latinised singular stela and Anglicised plural steles) is a stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected for funerary or commemorative purposes, most usually decorated with the names and titles of the deceased or living—inscribed, carved in relief (bas-relief, sunken-relief, high-relief, etc), or painted onto the slab.

Stelae were also used as territorial markers, as the boundary stelae of Akhenaton at Amarna, or to commemorate military victories. They were widely used in the Ancient Near East, Greece, Egypt, Ethiopia, and, quite independently, in China and some Buddhist cultures (see the Nestorian Stele), and, more surely independently, by Mesoamerican civilisations, notably the Olmec and Maya. The huge number of stelae surviving from ancient Egypt and in Central America constitute one of the largest and most significant sources of information on those civilisations. An informative stele of Tiglath-Pileser III is preserved in the British Museum. Two stelae built into the walls of a church are major documents relating to the Etruscan language.

Unfinished standing stones, set up without inscriptions from Libya in North Africa to Scotland were monuments of pre-literate Megalithic cultures in the Late Stone Age.

In 1489, 1512, and 1663 C.E., the Kaifeng Jews of China left these stone monuments to preserve their origin and history. Despite repeated flooding of the Yellow River, destroying their synagogue time and time again, these stelae survived to tell their tale.

An obelisk is a specialized kind of stele. The High crosses of Ireland, Scotland and Wales i.e. Celtic areas of Britain are specialized stelae. A modern gravestone with its inscribed epitaph is also a kind of stele.

Most recently, in the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, the architect Peter Eisenman created a field of some 2,700 blank stelae. The memorial is meant to be read not only as the field, but also as an erasure of data that refer to memory of the Holocaust.

Notable individual stelae

Gwanggaeto stele

The Gwanggaeto Stele (hangul=광개토대왕비 also 호태왕비 hanja=廣開土大王碑 also 好太王碑 Revised Romanization=Gwanggaeto Daewangbi also Hotae Wangbi McCune-Reischauer=Kwanggaet'o Taewangbi also Hot'ae Wangbi) of King Gwanggaeto of Goguryeo was erected in 414 by King Jangsu as a memorial to his deceased father. It is one of the major primary sources extant for the history of Goguryeo, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, and supplies invaluable historical detail on his reign as well as insights into Goguryeo mythology.

It stands near the tomb of Gwanggaeto in what is today the city of Ji'an along the Yalu River in present-day northeast China, which was the capital of Goguryeo at that time. It is carved out of a single mass of granite, stands nearly 7 meters tall and has a girth of almost 4 meters. The inscription is written exclusively in Classical Chinese and has 1802 characters.

The stele has also become a focal point of varying national rivalries in northeast Asia manifested in the interpretations of the stele's inscription and the place of the kingdom of Goguryeo in modern historical narratives. An exact replica of the Gwanggaeto Stele stands on the grounds of Seoul's National War Museum and the rubbed copies made in 1881 and 1883 are in the custody of China and the National Museum of Japan, respectively, testament to the stele's centrality in the history of Korea and Manchuria (Northeast China)

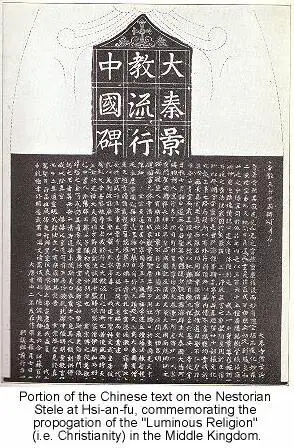

Nestorian stele

The Nestorian Stele or Nestorian Stone, formally the Memorial of the Propagation in China of the Luminous Religion from Daqin (大秦景教流行中國碑; pinyin: Dàqín Jǐngjiào liúxíng Zhōngguó béi, abbreviated 大秦景教碑), is a Tang Chinese stele erected in 781 which celebrates the accomplishments of the Assyrian Church of the East in China, which is also referred to as the Nestorian Church (albeit inaccurately).

The Nestorian Stele documents the existence of Christian communities in several cities in northern China and reveals that the church had initially received recognition by the Tang Emperor Taizong in 635. It is a 279-cm tall limestone block. It is also translated as A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom (the church referred to itself as "The Luminous Religion of Daqin," Daqin being the Chinese term for the Roman Empire).

It was erected on January 7, 781 at the imperial capital city of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an), or at nearby Chou-Chih (盩厔; Pinyin Zhouzhi). The calligraphy was by Lü Xiuyan (呂秀巖), and the content was composed by the Nestorian monk Jingjing (景淨) in the four- and six-character euphemistic style (駢體文) Chinese (total 1,756 characters) and a few lines in Syriac (70 words). On top of the tablet, there is a cross. Calling God "Veritable Majesty," the text refers to Genesis, the cross, and the baptism. It also pays tribute to missionaries and benefactors of the church, who are known to have arrived in China by 640.

The stele was unearthed in late Ming Dynasty (between 1623 and 1625) beside Chongren Temple (崇仁寺), where it was housed for several centuries. It is now displayed in the Stele Forest in Xi'an. For Chinese text and an English translation, see P. Y. Saeki, Nestorian Documents and Relics in China, 2nd ed., (Tokyo: Maruzen, 1951).

The Nestorian Stone has attracted the attention of some anti-Christian groups, who argue that the stone is a fake or that the inscriptions were modified by the Jesuits who served in the Ming Court. There is no scientific or historical evidence to support this claim.

Numerous Christian gravestones have also been found in China from a somewhat later period. There are also two much later stelae (from 960 and 1365) presenting a curious mix of Christian and Buddhist aspects, which are preserved at the site of the former Monastery of the cross in the Fangshan District, near Beijing; see A. C. Moule, Christians in China before the year 1550 (London: SPCK, 1930), pp.86-89.

Ukrainian stone stelae

The anthropomorphic Ukrainian stone stelae, with some finds extending the area to Moldavia, the northern Caucasus (Southern Federal District) and the area north of the Caspian Sea (western Kazakhstan), date from the Copper Age (ca. 4000 B.C.E.–2000 B.C.E.), through the Cimmerian period and Scythian and Sarmatian times to the early Slavs of the 1st millennium CE. They were first described by Erik Lasote, ambassador to emperor Rudolf, in 1594, who recorded

- "seven beacons, images cut from stone, and they numbered more than twenty and were standing atop the kurgans or barrows."

The earliest of these stelae date to the 4th millennium B.C.E., and are associated with the early Bronze Age Yamna and Kemi-Oba cultures (see Kurgan). They number in the hundreds, most of them very crude stone slabs with a simple schematic protruding head and a few features such as eyes or breasts carved into the stone. Some twenty specimens are more complex, featuring ornaments, weapons, human or animal figures etc.

The Cimmerians of the early 1st millennium B.C.E. left a small number (about ten are known) of distinctive stone stelae. Another four or five "deer stelae" dating to the same time are known from the northern Caucasus.

From the 7th century B.C.E., Scythian tribes began to dominate the Pontic steppe. They were in turn displaced by the Sarmatians from the 2nd century B.C.E., except for in the Crimea, where they persisted for a few centuries longer. These peoples left carefully crafted stone stelae, with all features cut in deep relief.

Stelae of early Slavic deities are again more primitive. There are some thirty sites of the middle Dniestr region where such anthropomorphic idols were found. The most famous of these is the "Zbruch idol" (ca. 10th century), a post measuring about 3 meters, with four faces under a single pointed hat (c.f. Svetovid). Boris Rybakov argued for identification of the faces with the gods Perun, Makosh, Lado and Veles.

Merneptah stele

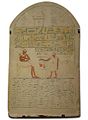

The Merneptah Stele (also known as the Israel Stele or Victory Stele of Merneptah) is the reverse of a large granite stele originally erected by the Ancient Egyptian king Amenhotep III, but later inscribed by Merneptah who ruled Egypt from 1213 to 1203 B.C.E. The black granite stela primarily commemorates a victory in a campaign against the Libu and Meshwesh Libyans and their Sea People allies, but its final two lines refer to a prior military campaign in Canaan in which Merneptah states that he defeated Ashkelon, Gezer, Yanoam and Israel among others.[1] The stele was discovered in the first court of Merneptah's mortuary temple at Thebes by Flinders Petrie in 1896.[2] Petrie remarked "This stele will be better known in the world than anything else I have found" [3]and is now in the collection of the Egyptian Museum at Cairo; a fragmentary copy of the stele was also found at Karnak.[4] It stands some ten feet tall, and its text is mainly a prose report with a poetic finish, mirroring other Egyptian New Kingdom stelae of the time. The stela is dated to Year 5, 3rd month of Shemu (summer), day 3 (c.1209/1208 B.C.E.), and begins with a laudatory recital of Merneptah's achievements in battle.

The stele has gained much notoriety and fame for being the only Egyptian document generally accepted as mentioning "Isrir" or "Israel." It is also, by far, the earliest known attestation of Israel. For this reason, many scholars refer to it as the "Israel stele." This title is somewhat misleading because the stele is clearly not concerned about Israel—it mentions Israel only in passing. There is only one line about Israel: "Israel is wasted, bare of seed" or "Israel lies waste, its seed no longer exists" and very little about the region of Canaan. Israel is simply grouped together with three other defeated states in Canaan (Gezer, Yanoam and Ashkelon) in the stele. Merneptah inserts just a single stanza to the Canaanite campaigns but multiple stanzas to his defeat of the Libyans. The line referring to Merneptah's Canaanite campaign reads: Canaan is captive with all woe. Ashkelon is conquered, Gezer seized, Yanoam made nonexistent; Israel is wasted, bare of seed.[1]

Mesha stele

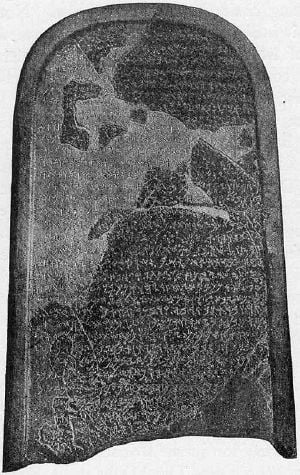

The Mesha Stele (popularized in the 19th century as the "Moabite Stone") is a black basalt stone, bearing an inscription by the 9th century B.C.E. Moabite King Mesha, discovered in 1868. The inscription of 34 lines, the most extensive inscription ever recovered from ancient Israel, was written in Paleo-Hebrew alphabet. It was set up by Mesha, about 850 B.C.E., as a record and memorial of his victories in his revolt against Israel, which he undertook after the death of his overlord, Ahab.

The stone is 124 cm high and 71 cm wide and deep, and rounded at the top. It was discovered at the ancient Dibon now Dhiban, Jordan, in August 1868, by Rev. F. A. Klein, a German missionary in Jerusalem. "The Arabs of the neighborhood, dreading the loss of such a talisman, broke the stone into pieces; but a squeeze had already been obtained by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, and most of the fragments were recovered and pieced together by him"[2]. A squeeze is a papier-mâché impression. The squeeze (which has never been published) and the reassembled stele (which has been published in many books and encyclopedias) are now in the Louvre Museum.

Boundary stelae of Akhenaten

The Boundary Stelae of Akhenaten map out the boundaries of the city of Akhetaten, the Ancient Egyptian city of Akhenaten.[5]

Many of the stelae are heavily eroded, but two of them have been protected and are easily visited. One is in the north of the city boundaries, by Tuna el-Gebel. The other is at the mouth of the Royal Wadi.

There were two phases of stelae, the four earliest (probably from Year 5 of Akhenaten's reign) were in the cliffs on the eastern bank of the Nile, to the north and south of the city of Akhetaten. These had copies of the same text in which the king told of how he planned the city, and was dedicating it to the Aten.

The later phase of stelae (from Year 6 of Akhenaten's reign) were used to properly define the area of land that were to be used by the city and surrounding farmlands. There are 11 of these and they all have the same text, but each have omissions and additions. They reaffirmed the dedication of the city and royal residences to the Aten.

Now as for the areas within these 4 landmarks, from the eastern mountain to the western mountain, it (is) Akhetaten itself. It belongs to my father Re–Horakhti–who–rejoices–in–lightland. In–his–name–Shu–who–is–Aten, who gives life forever; whether mountains or deserts or meadows or new lands or highlands or fresh lands or fields or water or settlements or shorelands or people or cattle or trees or all, anything, that the Aten, my father has made. I have made it for Aten, my father, forever and ever.[6]

Raimondi stela

The Raimondi Stela is a major piece of art of the Chavín culture of the central Andes. The stela is seven feet high, made of highly polished granite, with a very lightly incised design which is almost unnoticeable on the actual sculpture. For this reason, the design is best viewed from a drawing.

Chavín artists frequently made use of the technique of contour rivalry in their art forms, and the Raimondi Stela is frequently considered to be one of the finest known examples of this technique. Contour rivalry means that the lines in an image can be read in multiple ways, depending on which way the object is being viewed. In the case of the Raimondi Stela, when viewed one way, the image depicts a fearsome deity holding two staffs. His eyes look upward toward his large, elaborate headdress of snakes and volutes. This same image, when flipped upside-down, takes on a completely new life. The headdress now turns into a stacked row of smiling, fanged faces, while the deity's face has turned into the face of a smiling reptile as well. Even the deity's staffs now appear to be rows of stacked faces.

This technique speaks to larger Andean concerns of the duality and reciprocal nature of nature, life, and society - a concern that can also be found in the art of many other Andean civilizations.

Gallery

Ancient Egyptian funerary stele

Sueno's Stone in Forres, Scotland

Maya stela, Quirigua

Kildalton Cross 800 C.E. Islay, Scotland

Cantabrian Stele 200 B.C.E. Cantabria, Spain

A Buddhist Stele from China, Northern Wei period, built in the early 6th century

Notes

- ↑ Carol A. Redmount, 'Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt' in The Oxford History of the Biblical Word, ed: Michael D. Coogan, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.97

- ↑ Ian Shaw & Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, (1995), pp.183-184

- ↑ Flinders Petrie: A life in archaeology. Margaret Drower, 1985

- ↑ Redmount, Ibid., p.97

- ↑ Boundary Stelae. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ↑ Breasted, James H. (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Coogan, Michael D., 1999. The Oxford History of the Biblical Word, Oxford University Press

- Görg, Manfred. 2001. "Israel in Hieroglyphen." Biblische Notizen: Beiträge zur exegetischen Diskussion 106:21–27.

- Hasel, Michael G. 1994. "Israel in the Merneptah Stela." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 296:45–61.

- Hasel, Michael G. 1998. Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, 1300–1185 B.C.E. Probleme der Ägyptologie 11. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10984-6

- Hasel, Michael G. 2003. "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel" in Beth Alpert Nakhai ed. The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever, pp. 19–44. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 58. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. ISBN 0-89757-065-0

- Hasel, Michael G. 2004. "The Structure of the Final Hymnic-Poetic Unit on the Merenptah Stela." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 116:75–81.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. 1994. "The Physical Text of Merneptah's Victory Hymn (The 'Israel Stela')." Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 24:71–76.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. Ramesside Inscriptions, Translated & Annotated Translations. Volume 4: Merenptah & the Late Nineteenth Dynasty. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2003. ISBN 0-631-18429-5

- Kuentz, Charles. 1923. "Le double de la stèle d'Israël à Karnak." Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale 21:113–117.

- Lichtheim, Miriam. 1976. Ancient Egyptian Literature, A Book of Readings. Volume 2: The New Kingdom. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Manassa, Colleen. 2003. The Great Karnak Inscription of Merneptah: Grand Strategy in the Thirteenth Century B.C.E.. Yale Egyptological Studies 5. New Haven: Yale Egyptological Seminar, Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Yale University. ISBN 0-9740025-0-X

- Redford, Donald Bruce. 1992. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Stager, Lawrence E. 1985. "Merenptah, Israel and Sea Peoples: New Light on an Old Relief." Eretz Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographic Studies 18:56*–64*.

- Stager, Lawrence E. 2001. "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel" in Michael Coogan ed. The Oxford History of the Biblical World, pp. 90–129. New York: Oxford University Press.

- D. Ya Telegin, The Anthropomorphic Stelae of the Ukraine (1994).

External links

- stele text in English from researchers at Fordham University; actually 1919 translation of C. Horne

- "The Jesus Messiah of Xi'an" - translation and exposition of doctrinal passages in the stele text. From B. Vermander (ed.), Le Christ Chinois, Héritages et espérance, (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1998).

- [http://f17.aaa.livedoor.jp/~kmaz/keikyo/keikyou-hi.htm Photos of the actual Nestorian

- Raimondi Stela Full Image

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Stele history

- Nestorian_Stele history

- Ukrainian_stone_stela history

- Merneptah_Stele history

- Mesha_Stele history

- Boundary_Stelae_of_Akhenaten history

- Raimondi_Stela history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.