|

|

| (27 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | {{Claimed}} | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}} |

| | [[Category:Psychology]] | | [[Category:Psychology]] |

| | [[Category:Anthropology]] | | [[Category:Anthropology]] |

| | + | [[Category:Lifestyle]] |

| | + | [[Category:Marriage and family]] |

| | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] |

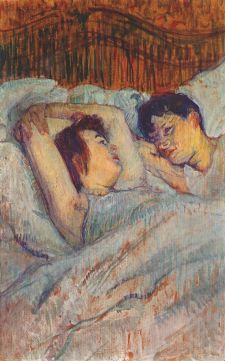

| − | | + | [[Image:Lautrec in bed 1892.jpg|thumb|225 px|[[Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec]]'s, ''In Bed'' (1892)]] |

| − | | + | A '''lesbian''' is a [[woman]] who is [[Romantic love|romantically]] and [[human sexuality|sexually]] attracted solely to other women. Women who are attracted to both women and men are more often referred to as [[bisexual]]. An individual's self-identification might not correspond with her behavior, and may be expressed with either, both, or neither of these words. The definition and social [[norm]]s, including public policy, concerning lesbians have evolved over the course of history. |

| − | | + | {{toc}} |

| − | | + | While male [[homosexuality]] has been well documented, albeit controversially, over the centuries and numerous cultures, female sexuality received much less attention. Many, in fact, regarded women as passive partners in sexual encounters, and that same-sex encounters were non-existent and of no interest to women. With the development of studies of sexology as well as the [[feminism|feminist]] movements in [[Europe]] and the [[United States]] in the twentieth century, lesbianism became more widely acknowledged. Lesbians have faced similar issues of discrimination, and the desire for same-sex marriage and the option of rearing children that male homosexuals have encountered. While the [[Gay rights movement|LGBT movement]] has gained ground in the acceptance of all people as members of [[society]], the issue of [[norm]]s of sexual behavior remains controversial. |

| − | A '''lesbian''' is a [[woman]] who is [[Romantic love|romantically]] and [[sexual relationship|sexually]] attracted only to other women.<ref>AskOxford.com [http://www.askoxford.com/results/?view=dict&field-12668446=lesbian&branch=13842570&textsearchtype=exact&sortorder=score%2Cname http://www.askoxford.com/results/?view=dict&field-12668446=lesbian&branch=13842570&textsearchtype=exact&sortorder=score%2Cname]</ref><ref>AskOxford.com [http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/homosexual?view=uk http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/homosexual?view=uk]</ref> Women who are attracted to both women and men are more often referred to as [[bisexual]]. An individual's self-identification might not correspond with her behaviour, and may be expressed with either, both, or neither of these words. | |

| | | | |

| | ==History== | | ==History== |

| − | The earliest known written references to same-sex love between women come from [[ancient Greece]]. [[Sappho]] (the [[eponym]] of "sapphism"), who lived on the island of [[Lesbos]], wrote poems which apparently expressed her sexual attraction to other females but some ancient accounts also describe her as having had love affairs with men. Moreover, [[Maximus of Tyre]] wrote that Sappho's relationships with the girls in her school were [[Platonic love|platonic]]{{Fact|date=April 2007}}. Modern scholarship suggests a parallel between the [[Pederasty in ancient Greece|ancient Greek constructs of love between men and boys]] and the friendships between Sappho and her students in which "both [[pedagogy]] and [[pederasty]] may have played a role."<ref>http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/bmcr/1999/1999-05-01.html</ref><ref>Ellen Greene (ed.), ''Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches.'' Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN 0-520-20195-7</ref> | + | {{readout||right|250px|The word "lesbian" is derived from the name of the Greek island of Lesbos, home to the poet [[Sappho]]}} |

| − | Lesbian relationships have also been cited in ancient [[Sparta]]. [[Plutarch]], writing about the Lacedaemonians, reports that "love was so esteemed among them that girls also became the erotic objects of noble women."<ref>"Lycurgus" 18.4) </ref>

| + | The earliest known written references to ''lesbian'' or same-sex love between women come from [[ancient Greece]]. [[Sappho]] (the [[eponym]] of "sapphism"), who lived on the island of [[Lesbos]] in the sixth century B.C.E., wrote [[poem]]s which apparently expressed her sexual attraction to other females. Hence the use of the term "Lesbian" to refer to same-sex relationships in women. However, some ancient accounts also describe her as having had love affairs with men. Moreover, [[Maximus of Tyre]] wrote that Sappho's relationships with the girls in her school were [[Platonic love|platonic]] (non sexual, or based on [[friendship]]). |

| − | Accounts of lesbian relationships are also found in poetry and stories from ancient [[China]], but are not documented with the detail given to male homosexuality. Research by anthropologist [[Liza Dalby]], based mostly on erotic poems exchanged between women, has suggested lesbian relationships were commonplace and socially accepted in Japan during the [[Heian Period]]. During medieval times in [[Arabia]] there were reports of relations between [[harem]] residents, although these were sometimes suppressed. For example, [[Caliph]] Musa [[al-Hadi]] ordered the beheading of two girls who were surprised during lovemaking.<ref>The History of al-Tabari, Vol. XXX, p.72-73, Albany: SUNY Press, Albany 1989).</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Public policy==

| |

| − | In [[Western societies]], explicit prohibitions on women's homosexual behavior have been markedly weaker than those on men's homosexual behavior.

| |

| | | | |

| − | In the [[United Kingdom]], lesbianism has never been illegal. In contrast, sexual activity between males was not made legal in [[England and Wales]] until 1967. It is said that lesbianism was left out of the [[Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885]] because Queen Victoria did not believe sex between women was possible, but this story may be apocryphal.<ref>{{cite book | last = Castle | first = Terry | title = The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture | publisher = Columbia University Press | date = 1993 | location = New York | id = ISBN 0-231-07652-5 | pages = 11, 66 }}</ref> A 1921 proposal, put forward by [[Frederick Alexander Macquisten|Frederick Macquisten]] MP to criminalize lesbianism was rejected by the [[House of Lords]]; during the debate, [[F. E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead|Lord Birkenhead]], the then [[Lord Chancellor of Great Britain|Lord Chancellor]] argued that 999 women out of a thousand had "never even heard a whisper of these practices."<ref>{{cite book | last = Doan | first = Laura | title = Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture | publisher = Columbia University Press | date = 2001 | location = New York | id = ISBN 0-231-11007-3 | pages = 56-60 }}</ref> In 1928, the lesbian novel ''[[The Well of Loneliness]]'' was banned for [[obscenity]] in a highly publicized trial, not for any explicit sexual content but because it made an argument for acceptance.<ref>Biron, Sir Chartres (1928). "Judgment". {{cite book | last = Doan | first = Laura | coauthors = Prosser, Jay | title = Palatable Poison: Critical Perspectives on ''The Well of Loneliness'' | publisher = Columbia University Press | date = 2001 | location = New York | id = ISBN 0-231-11875-9 | pages = 39-49}}</ref> Meanwhile other, less political novels with lesbian themes continued to circulate freely.<ref name="Foster">{{cite book | last = Foster | first = Jeanette H. | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Sex Variant Women in Literature: A Historical and Quantitative Survey | publisher = Vantage Press | date = 1956 | location = New York | pages = 287 }}</ref>

| + | Modern scholarship suggests a parallel between the ancient Greek [[pederasty]] (love between men and boys) and the friendships between Sappho and her students in which "both [[pedagogy]] and pederasty may have played a role."<ref>Ellen Greene (ed.), ''Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches'' (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996, ISBN 0520201957).</ref> Lesbian relationships have also been cited in ancient [[Sparta]]. [[Plutarch]], writing about the Lacedaemonians, reports that "love was so esteemed among them that girls also became the erotic objects of noble women."<ref>"Life of Lycurgus" 18.4.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Jewish religious teachings condemn male homosexual behavior but say little about lesbian behavior. However, the approach in the modern State of [[Israel]], with its largely [[secular]] Jewish majority, does not outlaw or persecute gay sexual orientation; marriage between gay couples is not sanctioned but [[common law]] status and official adoption of a gay person's child by his or her partner have been approved in precedent court rulings (after numerous high court appeals). There is also an annual Gay parade, usually held in [[Tel-Aviv]]; in 2006, the "World Pride" parade was slated to be held in Jerusalem.

| + | Research by [[anthropology|anthropologist]] [[Liza Dalby]], based mostly on erotic poems exchanged between women, has suggested lesbian relationships were commonplace and socially accepted in [[Japan]] during the [[Heian Period]]. Accounts of lesbian relationships are also found in [[poetry]] and stories from ancient [[China]], but are not documented with the detail given to male [[homosexuality]]. During medieval times in [[Arabia]] there were reports of relations between [[harem]] residents, although these were sometimes suppressed. For example, [[Caliph]] Musa [[al-Hadi]] ordered the [[beheading]] of two [[slave]] girls who were surprised during lovemaking.<ref> C.E. Bosworth (trans.), ''The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30'' (Albany: SUNY Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0887065644).</ref> |

| − | | |

| − | Western-style [[homosexuality]] is rarely tolerated elsewhere in the [[Muslim world]], with the possible exception of [[Turkey]]. It is punishable by imprisonment, lashings, or death in [[Saudi Arabia]] and [[Yemen]]. Though the law against lesbianism in [[Iran]] has reportedly been revoked or eased, prohibition of [[Gay men|male homosexuality]] remains.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Reproduction and parenting rights===

| |

| − | {{See also|Parenting by same-sex couples}}

| |

| − | In some countries access to assisted birth technologies by lesbians has been the subject of debate. In [[Australia]] the [[High Court of Australia|High Court]] rejected a [[Roman Catholic Church]] move to ban access to [[In vitro fertilization|in vitro fertilization (IVF)]] treatments for lesbian and single women. However, immediately after this High Court decision,[[Prime Minister of Australia| Prime Minister]] [[John Howard]] amended [[legislation]] in order to prevent access to IVF for these groups, effectively overruling the High Court decision and enforcing the Roman Catholic position, which raised indignation from the gay and lesbian community as well as groups representing the rights of single women.

| |

| − | Many lesbian couples seek to have children through [[Adoption by same-sex couples|adoption]], but this is not legal in every country.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Sexuality==

| |

| − | [[Image:Lautrec in bed 1893.jpg|thumb|left|250px|[[Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec]], ''In Bed'']] | |

| − | | |

| − | Sexual activity between women is as diverse as sex between [[heterosexuality|heterosexuals]] or [[homosexuality|gay men]]. Some women in same-sex relationships do not identify as lesbian, but as [[bisexuality|bisexual]], [[queer]], or another label. As with any interpersonal activity, sexual expression depends on the context of the relationship.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Recent cultural changes in [[Western society|western]] and a few other societies have enabled lesbians to express their sexuality more freely, which has resulted in new studies on the nature of female sexuality. Research undertaken by the U.S. Government's [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ National Center for Health Research] in 2002 was released in a 2005 report called 'Sexual Behavior and Selected Health Measures: Men and Women 15-44 Years of Age, United States, 2002'. The results indicated that among women aged 15-44, 4.4 percent reported having had a sexual experience with another woman during the previous 12 months. When women aged 15–44 years of age were asked, "Have you ever had any sexual experience of any kind with another female?" 11 percent answered "yes".

| |

| − | | |

| − | There is a growing body of [[research]] and writing on lesbian sexuality, which has brought some debate about the control women have over their sexual lives, the fluidity of woman-to-woman sexuality, the redefinition of female sexual pleasure and the debunking of negative sexual stereotypes. One example of the latter is ''[[lesbian bed death]]'', a term invented by sex researcher [[Pepper Schwartz]] to describe the supposedly inevitable diminution of sexual passion in long term lesbian relationships; this notion is rejected by many lesbians, who point out that passion tends to diminish in almost any relationship and many lesbian couples report happy and satisfying sex lives.

| |

| | | | |

| | ==Culture== | | ==Culture== |

| − | [[Image:Black triangle.svg|right|thumb|150px|The Black Triangle was used to identify "socially unacceptable" women in [[concentration camp]]s by the [[Nazi Germany|Nazis]]. Lesbians were included in this classification. Since then lesbians have appropriated the [[Black triangle (badge)|black triangle]] as a symbol of defiance against repression and discrimination as gay men have similarly appropriated the [[pink triangle]].]] | + | [[Image:Black triangle.svg|right|thumb|200px|The Black Triangle was used to identify "socially unacceptable" women in [[concentration camp]]s by the [[Nazi Germany|Nazis]]. Lesbians were included in this classification. Since then lesbians have appropriated the black triangle as a symbol of defiance against repression and discrimination as gay men have similarly appropriated the pink triangle]] |

| | | | |

| − | Throughout history [[List of gay, lesbian or bisexual people|hundreds of lesbians]] have been well-known figures in [[the arts]] and [[culture]].

| + | Before [[Europe]]an [[sexology]] emerged at the turn of the twentieth century, female homosexuality remained almost invisible compared to male [[homosexuality]], which was subject to the [[law]] and thus more regulated and reported by the press. However with the publication of works by sexologists like [[Karl Heinrich Ulrichs]], [[Richard von Krafft-Ebing]], [[Havelock Ellis]], [[Edward Carpenter]], and [[Magnus Hirschfeld]], the concept of active female homosexuality became better known. |

| | | | |

| − | Before the influence of European [[sexology]] emerged at the turn of the Twentieth Century, in cultural terms female homosexuality remained almost invisible as compared to male homosexuality, which was subject to the law and thus more regulated and reported by the press. However with the publication of works by sexologists like [[Karl Heinrich Ulrichs]], [[Richard von Krafft-Ebing]], [[Havelock Ellis]], [[Edward Carpenter]], and [[Magnus Hirschfeld]], the concept of active female homosexuality became better known.

| + | As female homosexuality became more visible it was initially described as a medical condition. In ''Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality'' (1905), [[Sigmund Freud]] referred to female homosexuality as "inversion" or "inverts" and characterized female inverts as possessing male characteristics. Freud drew on the "third sex" ideas popularized by Magnus Hirschfeld and others. While Freud admitted he had not personally studied any such "aberrant" patients he placed a strong emphasis on psychological rather than biological causes. |

| | | | |

| − | As female homosexuality became more visible it was described as a medical condition. In ''Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality'' (1905), [[Sigmund Freud]] referred to female homosexuality as ''inversion'' or ''inverts'' and characterised female inverts as possessing male characteristics. Freud drew on the "third sex" ideas popularized by Magnus Hirschfeld and others. While Freud admitted he had not personally studied any such "aberrant" patients he placed a strong emphasis on psychological rather than biological causes. Freud's writings did not become well-known in English-speaking countries until the late 1920s.

| + | This combination of [[sexology]] and [[psychoanalysis]] eventually had a lasting impact on the general tone of most lesbian cultural productions. A notable example is the 1928 novel ''The Well of Loneliness'' by [[Radclyffe Hall]], in which these sexologists are mentioned along with the term "invert." Freud's interpretation of lesbian behavior has since been rejected by most psychiatrists and scholars, although there has been [[biology|biological]] research that has provided findings that may bolster a Hirschfeld-ian "third sex" interpretation of same-sex attraction. |

| | | | |

| − | This combination of [[sexology]] and [[psychoanalysis]] eventually had a lasting impact on the general tone of most lesbian cultural productions. A notable example is the 1928 novel ''[[The Well of Loneliness]]'' by [[Radclyffe Hall]], in which these sexologists are mentioned along with the term ''invert'', which later fell out of favour in common usage. Freud's interpretation of lesbian behavior has since been rejected by most psychiatrists and scholars, although recent [[biology|biological]] research has provided findings that may bolster a Hirschfeld-ian "third sex" interpretation of same-sex attraction.

| + | During the twentieth century, lesbians such as [[Gertrude Stein]] and [[Barbara Hammer]] were noted in the U.S. [[avant-garde]] [[art]] movements, along with figures such as [[Madchen in Uniform|Leontine Sagan]] in [[Germany|German]] pre-war cinema. Since the 1890s the underground classic ''The Songs of Bilitis'' has been influential on lesbian culture. This book provided a name for the first campaigning and cultural organization in the United States, the [[Daughters of Bilitis]]. |

| | | | |

| − | During the twentieth century lesbians such as [[Gertrude Stein]] and [[Barbara Hammer]] were noted in the US [[avant-garde]] art movements, along with figures such as [[Madchen in Uniform|Leontine Sagan]] in [[Germany|German]] pre-war cinema. Since the [[1890s]] the underground classic ''[[The Songs of Bilitis]]'' has been influential on lesbian culture. This book provided a name for the first campaigning and cultural organization in the United States, the [[Daughters of Bilitis]]. | + | During the 1950s and 1960s lesbian pulp fiction was published in the U.S. and U.K., often under "coded" titles such as ''Odd Girl Out'', ''The Evil Friendship'' by [[Vin Packer]] and the ''Beebo Brinker'' series by [[Ann Bannon]]. British school stories also provided a haven for "coded" and sometimes outright lesbian fiction. |

| | | | |

| − | During the 1950s and 1960s lesbian pulp fiction was published in the US and UK, often under "coded" titles such as ''Odd Girl Out'', ''The Evil Friendship'' by [[Vin Packer]] and the [[Beebo Brinker]]-series by [[Ann Bannon]]. British school stories also provided a haven for "coded" and sometimes outright lesbian fiction. | + | During the 1970s the second wave of [[feminism|feminist]] era lesbian novels became more politically oriented. Works often carried the explicit ideological messages of [[separatist feminism]] and the trend carried over to other lesbian arts. [[Rita Mae Brown]]'s debut novel ''Rubyfruit Jungle'' was a milestone of this period. |

| | | | |

| − | During the 1970s the second wave of feminist era lesbian novels became more politically oriented. Works often carried the explicit ideological messages of [[separatist feminism]] and the trend carried over to other lesbian arts. [[Rita Mae Brown]]'s debut novel ''[[Rubyfruit Jungle]]'' was a milestone of this period. By the early 1990s lesbian culture was being influenced by a younger generation who had not taken part in the "[[Feminist Sex Wars]]" and this strongly informed post-feminist [[Queer|queer theory]] along with the new queer culture.

| + | In 1972 the [[Berkeley]], [[California]] lesbian journal ''[[Libera (journal)|Libera]]'' published a paper entitled "Heterosexuality in Women: its Causes and Cure." Written in deadpan, academic prose, closely paralleling previous [[psychiatry]]-journal articles on homosexuality among women, this paper inverted prevailing assumptions about what is normal and deviant or pathological and was widely read by lesbian feminists. |

| | | | |

| − | In 1972 the [[Berkeley, California]] lesbian journal [[Libera (journal)|Libera]] published a paper entitled ''Heterosexuality in Women: its Causes and Cure''. Written in deadpan, academic prose, closely paralleling previous psychiatry-journal articles on homosexuality among women, this paper inverted prevailing assumptions about what is normal and deviant or pathological and was widely read by lesbian feminists.

| + | Since the 1980s lesbians have been increasingly visible in mainstream cultural fields such as [[music]] ([[Melissa Etheridge]], [[K.D. Lang]], and the [[Indigo Girls]]), [[sports]] ([[Martina Navrátilová]] and [[Billie Jean King]]), and in comic books ([[Alison Bechdel]] and [[Diane DiMassa]]). Lesbian eroticism has flowered in [[fine art photography]] and the writing of authors such as [[Pat Califia]], [[Jeanette Winterson]], and [[Sarah Waters]]. There is also a significant body of lesbian [[film]]s. Classic novels such as those by [[Jane Rule]] have been reprinted. Moreover, prominent and controversial academic writers such as [[Camille Paglia]] and [[Germaine Greer]] also identify with lesbianism. |

| | | | |

| − | Since the 1980s lesbians have been increasingly visible in mainstream cultural fields such as music ([[Melissa Etheridge]], [[K.D. Lang]] and the [[Indigo Girls]]), sports ([[Martina Navrátilová]] and [[Billie Jean King]]) and in comic books ([[Alison Bechdel]] and [[Diane DiMassa]]). More recently lesbian eroticism has flowered in [[fine art photography]] and the writing of authors such as [[Pat Califia]], [[Jeanette Winterson]] and [[Sarah Waters]]. There is an increasing body of lesbian films such as ''[[Desert Hearts]]'', ''[[Go Fish (Film)|Go Fish]]'', ''[[Loving Annabelle]]'', ''[[Watermelon Woman]]'', ''[[Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit (television programme)|Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit]]'', ''[[Everything Relative]]'', and ''[[Better than Chocolate]]'' (see [[List of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender-related films]]). Classic novels such as those by [[Jane Rule]] have been reprinted. Moreover, prominent and controverisal academic writers such as [[Camille Paglia]] and [[Germaine Greer]] also identify with lesbianism.

| + | ==Lesbianism and Feminism== |

| | + | [[File:Lesbian married couple.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Same-sex married couple]] at [[San Francisco Pride]] 2004.]] |

| | + | Historically, many lesbians have been involved in [[women's rights]]. Late in the nineteenth century, the term ''[[Boston marriage]]'' was used to describe romantic unions between women living together while contributing to the [[suffrage]] movement. Continuing this tradition, in 2004, [[Massachusetts]] became the first [[United States|American]] state to legalize same-sex marriages.<ref> Jone Johnson Lewis, [https://www.thoughtco.com/boston-marriage-definition-3528567 Boston Marriage: Women Living Together, 19th/20th Century Style] ''ThoughtCo'', July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2021.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | ==Media depictions==

| + | During the 1970s and 1980s, with the emergence of modern feminism and the [[radical feminism]] movement, ''[[lesbian separatism]]'' became popular and groups of lesbian women gathered together to live in [[communal]] societies. Women such as [[Kathy Rudy]] remarked that in her experience, [[stereotype]]s and the [[hierarchy|hierarchies]] to reinforce them developed in the lesbian separatist collective she lived in, ultimately leading her to leave the group.<ref>Kathy Rudy, Radical Feminism, Lesbian Separatism, and Queer Theory ''Feminist Studies'' 27(1) (Spring, 2001): 190-222.</ref> |

| − | Lesbians often attract media attention, particularly in relation to [[feminism]], love and sexual relationships, [[same-sex marriage|marriage]], and [[parent]]ing.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Cinema===

| + | There is a body of research and writing on lesbian sexuality which has brought some debate about the control women have over their sexual lives, the fluidity of woman-to-woman sexuality, the redefinition of female sexual pleasure, and the debunking of negative sexual stereotypes. One example of the latter is ''[[lesbian bed death]]'', a term invented by sex researcher [[Pepper Schwartz]] to describe the supposedly inevitable diminution of sexual passion in long term lesbian relationships; this notion has been rejected by many lesbians, who pointed out that passion tends to diminish in almost any relationship and many lesbian couples have reported happy and satisfying sex lives. |

| − | {{See also|List of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender-related films}}

| |

| − | '' (Germany, 1931), the first lesbian feature film. It was immediately banned in the United States but then released in a heavily cut version. It was later banned in Nazi Germany, after which director Leontine Sagan and many of the cast fled the country (scriptwriter [[Christa Winsloe]] eventually joined the [[French resistance]] and was executed by the Nazis in 1944).]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | The first lesbian-themed feature film was ''[[Madchen in Uniform|Mädchen in Uniform]]'' (1931), based on a novel by [[Christa Winsloe]] and directed by [[Leontine Sagan]], tracing the story of a schoolgirl called Manuela von Meinhardis and her passionate love for a teacher, Fräulein von Nordeck zur Nidden. It was written and mostly directed by women. The impact of the film in Germany's lesbian clubs was overshadowed, however, by the cult following for ''[[Der blaue Engel|The Blue Angel]]'' (1930). | + | ===Transgender issues=== |

| | + | The relationship between lesbianism and lesbian-identified [[transgender]] or [[transsexual]] women has been a turbulent one, with historically negative attitudes. Some lesbian groups openly welcome transsexual women and may even welcome ''any'' member who identifies as lesbian, but a few groups do not welcome [[transwomen]]. |

| | | | |

| − | Until the early 1990s, any notion of lesbian love in a film almost always required audiences to infer the relationships. The lesbian aesthetic of ''[[Queen Christina (film)|Queen Christina]]'' (1933) with Greta Garbo has been widely noted, even though the film is not about lesbians. Alfred Hitchcock's ''[[Rebecca (film)|Rebecca]]'' (1940), based on the novel by [[Daphne du Maurier]], referred more or less overtly to lesbianism, but the two characters involved were not presented positively: Mrs. Danvers was portrayed as obsessed, neurotic and murderous, while the never-seen Rebecca was described as having been selfish, spiteful and doomed to die. ''[[All About Eve]]'' (1950) was originally written with the title character as a lesbian but this was very subtle in the final version, with the hint and message apparent to alert viewers.

| + | Disputes in defining the term "lesbian" along with enforced exclusions from lesbian events and spaces have been numerous. Some who hold a non-inclusionist attitude often make reference to strong, typically [[second-wave feminism|second-wave feminist]] ideas such as those of [[Mary Daly]], who has described post-operative male-to-female (MTF) transsexuals as "'constructed women." They may attribute transsexualism to mechanisms of [[patriarchy]] or do not recognize a MTF transsexual's identification as female and lesbian. By defining "lesbian" through these views, they defend the non-inclusion of women with transsexual or transgender-backgrounds. |

| | | | |

| − | Playwright [[Lillian Hellman]]'s first play, ''[[The Children's Hour (play)|The Children's Hour]]'' (1934) was produced on Broadway. Set in a private girls' boarding school, the headmistress and a teacher are the targets of a malicious whispering campaign of insinuation by a disgruntled schoolgirl. They soon face public accusations of having a lesbian relationship.<ref>http://www.enotes.com/feminism-literature/hellman-lillian</ref>

| + | Inclusionists claim these attitudes are inaccurate and derive from fear and distrust, or that the motivations and attitudes of transgender or transsexual lesbians are not well understood, and so they defend the inclusion of transwomen into lesbianism and lesbian spaces. |

| − | The play was nominated for a Pulitzer prize, banned in [[Boston]], [[London]], and [[Chicago]]<ref>http://classiclit.about.com/od/bannedliteratur1/tp/aatp_bannedplay.htm</ref> and had a record-breaking run of 691 consecutive performances in [[New York]].<ref>http://www.playersring.org/2004_2005_Season/Children's_Hour.htm</ref> A 1961 ''[[The Children's Hour (1961 film)|screen adaptation]]'' starred [[Audrey Hepburn]] and [[Shirley MacLaine]]. The play's deep and pervasively dark themes and lesbian undertones have been widely noted.<ref>http://gayleft1970s.org/issues/gay.left_issue.05.pdf</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | Mainstream films with openly lesbian content, sympathetic lesbian characters and lesbian leads began appearing during the [[1990s]]. By 2000 some films portrayed characters exploring issues beyond their sexual orientation, reflecting a wider sense that lesbianism has to do with more than sexual desire. Notable mainstream theatrical releases included ''[[Bound (film)|Bound]]'' (1996), ''[[Chasing Amy]]'' (1997), ''[[Kissing Jessica Stein]]'' (2001), ''[[Boys Don't Cry]]'', ''[[Mulholland Drive (film)|Mulholland Drive]]'', ''[[Monster]]'', ''[[RENT|Rent]]'' (2005, based on the Jonathan Larson musical) and ''[[Loving Annabelle]]'' (2006). There have also been many non-English language lesbian films such as ''[[Fire (film)|Fire]]'' (India, 1996), ''[[Fucking Åmål]]'' (Sweden, 1998), ''[[Blue (2001 film)|Blue]]'' (Japan, 2002), and ''[[Blue Gate Crossing]]'' (Taiwan, 2004).

| + | One incident due to this divisiveness arose during the early 1990s in [[Australia]], when the wider lesbian community raised money to purchase a building devoted to lesbian women called The Lesbian Space Project. Before the organization bought the building, a debate over inclusion of transwomen polarized the lesbian community, the building was later closed, the funds were invested and instead generated money for an annual Australian lesbian grants program called LInc (Lesbians Incorporated). |

| | | | |

| − | ===Mainstream broadcast media=== | + | ==Public policy== |

| − | The 1980s television series ''[[L.A. Law]]'' included a lesbian relationship which stirred much more controversy than lesbian TV characters would a decade later. The 1989 [[BBC]] mini series ''[[Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit (television programme)|Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit]]'' was based on lesbian writer [[Jeanette Winterson]]'s novel of the same title. Russian pop-duo [[T.A.T.u.|t.A.T.u]] were popular in Europe during the early 2000s, gaining wide attention and TV airplay for their [[pop video]]s because they were marketed as lesbians even though they weren't.

| + | In [[Western societies]], explicit prohibitions on women's homosexual behavior have been markedly weaker than those on men's homosexual behavior. |

| | | | |

| − | Many SciFi series have featured lesbian characters. An episode of ''[[Babylon 5]]'' featured an implied lesbian relationship between characters [[Talia Winters]] and [[Commander Susan Ivanova]]. ''[[Star Trek: Deep Space 9]]'' featured several episodes with elements of lesbianism and made it clear that in Star Trek's 24th century such relationships are accepted without a second thought.

| + | In the [[United Kingdom]], lesbianism has never been illegal. In contrast, sexual activity between males was not made legal in [[England]] and [[Wales]] until 1967. It is said that lesbianism was left out of the [[Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885]] because [[Queen Victoria]] did not believe sex between women was possible, although this story may be apocryphal.<ref>Terry Castle, ''The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture'' (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993, ISBN 0231076525), 11, 66. </ref> A 1921 proposal put forward by [[Frederick Alexander Macquisten|Frederick Macquisten]] MP to criminalize lesbianism was rejected by the [[House of Lords]]; during the debate, [[F.E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead|Lord Birkenhead]], then [[Lord Chancellor of Great Britain|Lord Chancellor]] argued that 999 women out of a thousand had "never even heard a whisper of these practices."<ref> Laura Doan, ''Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture'' New York: Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 0231110073), 56-60.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Actress and comedian [[Ellen DeGeneres]] came out publicly as a lesbian in 1997 and her character on the sitcom ''[[Ellen (television series)|Ellen]]'' did likewise soon after during its fourth season. This was the first American sitcom with a lesbian lead character. The coming-out episode won an [[Emmy Award]] but the series was cancelled after one more season. In 2000 the ABC Daytime Drama Series ''[[All My Children]]'' character Bianca Montgomery ([[Eden Riegel]]) was revealed to be lesbian. While many praised the character's prominent storyline, others criticised the almost perpetual trauma and Bianca's lack of a successful long-running relationship with another woman. In 2004's popular television show on Showtime, ''[[The L Word]]'' is focused on a group of lesbian friends living in L.A., and [[Ellen DeGeneres]] had a popular daytime talk show. In 2005 an episode of ''[[The Simpsons]]'' ("[[There's Something About Marrying]]") depicted [[Marge Simpson|Marge's]] sister [[Patty Bouvier|Patty]] coming out as a lesbian. Also that year on ''[[Law & Order]]'' the final appearance of [[assistant district attorney]] [[Serena Southerlyn]] included the revelation she was a lesbian, although some viewers claimed there had been hints of this in previous episodes. [[Chris Rock]] on [[Saturday Night Live]] commented that the [[Peanuts]] character [[Peppermint Patty]] is a lesbian (''Peppermint Patties'' is a sometimes perjorative slang word for lesbians).

| + | In 1928, the lesbian novel ''The Well of Loneliness'' was banned for [[obscenity]] in a highly publicized [[trial]], not for any explicit sexual content but because it made an argument for acceptance.<ref> Sir Chartres Biron, 1928, "Judgment," Laura Doan, and Jay Prosser, ''Palatable Poison: Critical Perspectives on The Well of Loneliness'' (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 0231118759), 39-49.</ref> Meanwhile other, less political novels with lesbian themes continued to circulate freely,<ref> Jeanette H. Foster, ''Sex Variant Women in Literature: A Historical and Quantitative Survey'' (New York: Vantage Press, 1956), 287. </ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Notable lesbian characters and appearances in the mainstream media have included:

| + | [[Jewish]] religious teachings condemn male homosexual behavior but say little about lesbian behavior. However, the approach in the modern state of [[Israel]], with its largely [[secular]] Jewish majority, does not outlaw or persecute gay sexual orientation; [[marriage]] between gay couples is not sanctioned but [[common law]] status and official [[adoption]] of a gay person's child by his or her partner have been approved in precedent court rulings (after numerous high court appeals). |

| | | | |

| − | *Kim Daniels in the UK TV series ''[[Sugar Rush (TV series)|Sugar Rush]]''

| + | Western-style [[homosexuality]] is rarely tolerated elsewhere in the [[Muslim]] world, with the possible exception of [[Turkey]]. It is punishable by [[prison|imprisonment]], lashings, or [[death penalty|death]] in [[Saudi Arabia]] and [[Yemen]]. Though the law against lesbianism in [[Iran]] has reportedly been revoked or eased, prohibition of male homosexuality remains. |

| − | *Liz Cruz in ''[[Nip/tuck|Nip/Tuck]]''

| |

| − | *[[Willow Rosenberg]], [[Tara Maclay]] and [[Kennedy (Buffyverse)|Kennedy]] in ''[[Buffy the Vampire Slayer]]''

| |

| − | *Lindsay Peterson and Melanie Marcus in ''[[Queer as Folk (US)|Queer as Folk]]''

| |

| − | *Maia Jefferies and Jay Copeland in ''[[Shortland Street]]''

| |

| − | *Lana Crawford and Georgina Harris in ''[[Neighbours]]''

| |

| − | *[[Amanda Donohoe]] (as C.J.Lamb) and Michelle Green (as Abbey Perkins) in ''[[LA Law]]''

| |

| − | *Dr. [[Kerry Weaver]] and Sandy López in ''[[ER (TV series)|ER]]''

| |

| − | *Helen Stewart and Nikki Wade in ''[[Bad Girls (television series)|Bad Girls]]''

| |

| − | *[[Paige Michalchuk]] and [[Alex Núñez]] in ''[[Degrassi: The Next Generation|Degrassi:The Next Generation]]

| |

| − | *Dorothy's college friend Jean in ''[[The Golden Girls]]''

| |

| − | *[[Alice Pieszecki]], [[Dana Fairbanks]], [[Bette Porter]], [[Shane McCutcheon]], [[Tina Kennard]], [[Jodi Lerner]], [[Helena Peabody]], [[Phyllis Kroll]], [[Jennifer Schecter]], and several others in ''[[The L Word]]''

| |

| − | *[[Anna Friel]] and [[Nicola Stephenson]] on the UK series ''[[Brookside]]''

| |

| − | *[[Spencer Carlin]] and Ashley Davies in ''[[South of Nowhere]]''

| |

| − | *Carol, Ross' ex-wife and her life partner Susan on ''[[Friends]]''

| |

| − | *[[Sharon Stone]] and [[Ellen Degeneres]] in ''[[If These Walls Could Talk 2]]''

| |

| − | *Jennifer K. Buckmeyer in the made for TV special ''[[Coming Out]]''

| |

| − | *Marissa Cooper and Alex Kelly on ''[[The OC]]''

| |

| − | *[[Patty Bouvier]], sister of Marge Simpson, on ''[[The Simpsons]]''

| |

| − | *[[Naomi Julien]], [[Della Alexander]] and [[Binnie Roberts]] in ''[[EastEnders]]''

| |

| − | *Thelma Bates in ''[[Hex (TV series)|Hex]]''

| |

| − | *Jessica Sammler and Katie Singer on ''[[Once and Again]]''

| |

| − | *[[Jasmine Thomas]] and [[Debbie Dingle]], and [[Zoe Tate]] in ''[[Emmerdale]]

| |

| − | *[[Maggie Sawyer]] and [[Toby Raines]] (implied) in ''[[Superman: The Animated Series]]''

| |

| − | *Beverly Harris, Nancy Bartlett and Jackie Harris in ''[[Roseanne (TV series)|Roseanne]]''

| |

| − | *[[Maxine Proctor]] (implied) in ''[[In Diana Jones]]''

| |

| − | *Frankie Doyle, Angela Jeffries, Sharon Gilmore, Judy Bryant, Joan Ferguson, Audrey Forbes, Terri Malone in ''[[Prisoner: Cell Block H ]]'' (TV series - 1979-1986)

| |

| − | *[[Serena Southerlyn]] on ''[[Law And Order]]''

| |

| − | *[[Christina Ricci]] and [[Charlize Theron]] in ''[[Monster (film)|Monster]]''

| |

| − | *[[Xena]] and [[Gabrielle (Xena)|Gabrielle]] (implied) in ''[[Xena: Warrior Princess]]''

| |

| − | *[[Penelope Cruz]] and [[Charlize Theron]] in "[[Head in the Clouds]]"

| |

| − | *[[Piper Perabo]] and [[Jessica Paré]] in "[[Lost and Delirious]]"

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Comics=== | + | ===Reproduction and parenting rights=== |

| − | {{details|LGBT comic book characters}}

| + | Family issues were significant concerns for lesbians when gay activism became more vocal in the 1960s and 1970s. Custody issues in particular were of interest since often courts would not award custody to mothers who were openly homosexual. |

| − | | |

| − | Until 1989 the [[Comics Code Authority]], which imposed ''[[de facto]]'' censorship on comics sold through newsstands in the United States, forbade any suggestion of homosexuality.<ref>{{cite book | last = Nyberg | first = Amy Kiste | title = Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code | publisher = University Press of Mississippi | date = 1998 | location = Jackson | pages = 143, 175-176 | id = ISBN 0-878-05975-X }}</ref> Overt lesbian themes were first found in [[underground comics|underground]] and [[alternative comics|alternative]] titles which did not carry the Authority's seal of approval. The first comic with an openly lesbian character was "Sandy Comes Out" by [[Trina Robbins]], published in the anthology ''[[Wimmen's Comix]]'' #1 in 1972.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Bernstein | first = Robin | coauthors = | title = Where Women Rule: The World of Lesbian Cartoons | journal = The Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review | volume = 1 | issue = 3 | pages = 20 | date = [[July 31]], [[1994]]}}</ref> ''Gay Comix'' (1980) included stories by and about lesbians and by 1985 the influential alternative title ''[[Love and Rockets (comics)|Love and Rockets]]'' had revealed a relationship between two major characters, Maggie and Hopey.<ref>[[Jaime Hernandez]], "Locas", reprinted in {{cite book | last = Hernandez | first = Los Bros | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = House of Raging Women| publisher = Fantagraphics Books| date = 1988| location = Seattle, WA| pages = 74-81 | id = ISBN 0-930193-69-5 }}</ref> Meanwhile mainstream publishers were more reticent. A relationship between the female [[Marvel comics]] characters [[Mystique (comics)|Mystique]] and [[Destiny (Irene Adler)|Destiny]] was only implied at first, then cryptically confirmed in 1990 through the use of the archaic word ''[[wikt:leman|leman]]'', meaning a lover or sweetheart.<ref>Uncanny X-Men #265 (Early August, 1990).</ref> Only in 2001 was Destiny referred to in plain language as Mystique's lover.<ref>''X-Men Forever'' #5 (May, 2001).</ref> In 2006 [[DC Comics]] could still draw widespread media attention by announcing a new, lesbian incarnation of the well-known character [[Batwoman]]<ref>{{cite news | last = Ferber | first = Lawrence | title = Queering the Comics | work = The Advocate | pages = 51 | publisher = | date = [[July 18]], [[2006]]}}</ref> even while openly lesbian characters such as [[Gotham City]] police officer [[Renee Montoya]] already existed in DC Comics.<ref>{{cite news | last = Mangels | first = Andy | title = Outed in Batman's Backyard | work = The Advocate | pages = 62 | date = [[May 27]], [[2003]] }}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In [[2006]], the [[graphic novel|graphic memoir]] ''[[Fun Home|Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic]]'' by [[Alison Bechdel]], was lauded by many media as among the best books of the year. Bechdel is the author of ''[[Dykes to Watch Out For]]'', one of the best-known and longest-running LGBT comic strips.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In [[manga]] and [[anime]], lesbian content is called [[shoujo-ai]] (literally: girl-love) whereas lesbian sex is called [[yuri (animation)|yuri]], which may have a derogatory meaning. A main theme of the [[Japanese culture|Japanese]] graphic novel [[Yokohama Kaidashi Kikō]] is the developing romance between characters Alpha and Kokone.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Anime===

| |

| − | The third season of the [[anime]] series [[Sailor Moon]], [[Sailor Moon S]] features a lesbian relationship between the two heroines [[Sailor Uranus]] and [[Sailor Neptune]]. However the season was heavily censored when dubbed and shown on TV in the United States. All the scenes which would suggest this particular relationship were cut away and the two characters were depicted as cousins (this led to further controversy as many fans noticed the editing). In the ''[[Azumanga Daioh]]'' series, the girl Kaorin is depicted as having a deep love (though not necessarily a sexual one) for Miss Sakaki, the tall, strong, fast, "cool" girl of the bunch. Kaorin adores her, loves being in her presence and feels jealous of anything that might stop her from being with Sakaki. Kaorin says she "could die right now" when she dances with Sakaki after being shifted to the boys' side of a folk-dance circle to help even out the dancers. In many of the [[mangaka]] group [[Clamp (manga artists)|Clamp]]'s series such as ''Alice In Wonderland'' or ''[[Card Captor Sakura]]'' , some characters (like Alice) are clearly lesbians and fans speculate about others (like Tomoyo in CCS).

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Games===

| |

| − | {{details|Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender characters in video and computer games}}

| |

| − | [[SaGa Frontier]] (a [[PlayStation]] title produced by [[Squaresoft]]) has a lesbian character named [[Asellus (Saga Frontier character)|Asellus]]. Another character named Gina is a young girl who tailors Asellus' outfits, often discusses her deep attraction to Asellus and becomes her bride in one of the game's many endings. However, much related dialogue and some content has been edited out of the English language version.<ref>http://polish.imdb.com/title/tt0207072/alternateversions</ref> The Playstation title [[Fear Effect 2: Retro Helix]] (a prequel to [[Fear Effect]]) reveals that Hana Tsu Vachel, a main character in both games, had a sexual relationship with a female character named Rain Qin.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Feminism==

| |

| − | [[Image:Lesbian married couple.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Same-sex married couple]] at [[San Francisco Pride]] [[2004]].]]

| |

| − | Historically, many lesbians have been involved in [[women's rights]]. Late in the [[19th century]], the term ''[[Boston marriage]]'' was used to describe romantic unions between women living together while contributing to the [[suffrage]] movement. Continuing a tradition of inclusive acceptance, in [[2004]] [[Massachusetts]] became the first [[United States|American]] state to legalize [[same-sex marriages]].<ref>http://www.glbtq.com/social-sciences/boston_marriages.html</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | During the 1970s and 80s, with the emergence of modern feminism and the [[radical feminism]] movement, ''[[lesbian separatism]]'' became popular and groups of lesbian women gathered together to live in [[communal]] societies. Women such as [[Kathy Rudy]] in ''Radical Feminism, Lesbian Separatism, and [[Queer Theory]]'' remarked that in her experience, [[stereotypes]] and the [[hierarchy|hierarchies]] to reinforce them developed in the lesbian separatist collective she lived in, ultimately leading her to leave the group.

| |

| | | | |

| − | During the 1990s, dozens of chapters of [[Lesbian Avengers]] were formed to press for lesbian visibility and rights.

| + | Also, many lesbian couples seek to have children through [[adoption]], domestically or internationally, or provide a home as a [[foster parent]], but this is not legal in every country. Access to in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments is also the subject of debate in many countries. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Transwomen and trans-inclusion=== | + | ==Notes== |

| − | The relationship between lesbianism and [[lesbian-identified]] [[transgender]] or [[transsexual]] women has been a turbulent one, with historically negative attitudes, but this seemed to be changing by the close of the twentieth century.

| + | <references/> |

| − | | |

| − | Some lesbian groups openly welcome transsexual women and may even welcome ''any'' member who identifies as lesbian, but a few groups still do not welcome [[transwomen]]. The Lesbian Avengers have historically had a very inclusive policy.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Disputes in defining the term ''lesbian'' along with enforced exclusions from lesbian events and spaces have been numerous. Some who hold a non-inclusionist attitude often make reference to strong, typically [[second-wave feminism|second-wave feminist]] ideas such as those of [[Mary Daly]], who has described post-operative male-to-female (MTF) transsexuals as ''constructed women''. They may attribute transsexualism to mechanisms of patriarchy or do not recognize a MTF transsexual's identification as female and lesbian. By defining ''lesbian'' through these views, they subsequently defend the non-inclusion of women with transsexual or transgender-backgrounds.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Inclusionists claim these attitudes are inaccurate and derive from fear and distrust, or that the motivations and attitudes of transgender or transsexual lesbians are not well understood, and so they defend the inclusion of transwomen into lesbianism and lesbian spaces.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Both views are common. One incident due to this divisiveness arose during the early 1990s in [[Australia]], when the wider lesbian community raised money to purchase a building devoted to lesbian women called ''The Lesbian Space Project''. Before the organisation bought the building, a debate over inclusion of transwomen polarised the lesbian community, the building was later closed, the funds were invested and now generate money for an annual Australian lesbian grants program called LInc (Lesbians Incorporated).

| |

| − | | |

| − | An example often cited among the transgender and transsexual communities is the [[Michigan Womyn's Music Festival]], a well-known and primarily lesbian event restricted to ''womyn-born [[womyn]]''. [[Camp Trans]], an organization oriented towards transwomen, was started as a result.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==See also==

| |

| − | {{Portal|LGBT|Gay_flag.svg}}

| |

| − | *[[Gay]]

| |

| − | *[[Black triangle (badge)|Black triangle]]

| |

| − | *[[Butch and femme]]

| |

| − | *[[Soft butch]]

| |

| − | *[[Tomboy]]

| |

| − | *[[Feminism]]

| |

| − | *[[Homosexuality]]

| |

| − | *[[Lesbian feminism]]

| |

| − | *[[Lesbian fiction]]

| |

| − | *[[Lesbian literature]]

| |

| − | *[[Lesbian science fiction]]

| |

| − | *[[Lesbian until graduation]]

| |

| − | *[[Lipstick lesbian]] and [[Chapstick lesbian]]

| |

| − | *[[Lesbianism in erotica]]

| |

| − | *[[List of LGBT-related organizations]]

| |

| − | *[[List of gay, lesbian or bisexual people]]

| |

| − | *[[List of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender-related films]]

| |

| − | *[[List of gay-related topics]]

| |

| − | *[[List of transgender-related topics]]

| |

| − | *[[The Ladder (Magazine)|The Ladder]]

| |

| − | *[[Shoujo-ai]]

| |

| − | *[[Lesbian teen fiction]]

| |

| − | *[[Terminology of homosexuality]]

| |

| − | *[[Tribadism]]

| |

| − | *[[Woman]]

| |

| − | *[[Drag king]]

| |

| − | *[[U-Haul lesbian]]

| |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − | {{reflist|2}}

| + | *Abelove, Henry. ''The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader''. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415905192 |

| − | | + | *Bosworth C.E. (trans.). ''The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30''. Albany: SUNY Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0887065644 |

| − | ==External links==

| + | *Castle, Terry. ''The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. ISBN 0231076525 |

| − | *[http://www.pinklemonz.com/articles/bed_death.htm Criticism of Lesbian Bed Death] | + | *Clifford, Denis. ''A Legal Guide for Lesbian & Gay Couples''. NOLO, 2007. ISBN 1413306292 |

| − | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/1936952.stm Australia backs lesbian IVF treatment - BBC News Online] | + | *Clunis, D. Merilee. ''Lesbian Couples: A Guide to Creating Healthy Relationships''. Seal Press, 2004. ISBN 1580051316 |

| − | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/864803.stm Lesbians protest IVF ban plan - BBC News Online]

| + | *Doan, Laura. ''Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture''. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001. ISBN 0231110073) |

| − | *[http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99996670 Lesbian couples raise teenagers just as decent as heterosexuals] | + | *Doan, Laura, and Jay Prosser. ''Palatable Poison: Critical Perspectives on The Well of Loneliness''. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001. ISBN 0231118759 |

| − | *[http://www.nclrights.org The National Center for Lesbian Rights]

| + | *Foster, Jeanette H. ''Sex Variant Women in Literature: A Historical and Quantitative Survey''. New York: Vantage Press, 1956. |

| − | *[http://www.oloc.org/ Old Lesbians Organizing for Change (OLOC)] | + | *Freud, Sigmund. ''Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality''. Alicia Editions, 2020. ISBN 978-2357284852 |

| − | *[http://www.commondreams.org/headlines02/0608-02.htm An article on World Pride 2006, to be held in Jerusalem, Israel]

| + | *Greene, Ellen (ed.). ''Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN 0520201957 |

| − | *[http://www.worldpride.net/ World Pride 2006 Site]

| + | *Stevens, Tracey. ''How To Be A Happy Lesbian: A Coming Out Guide''. Amazing Dreams Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0971962804 |

| − | *[http://www.GayandLesbianWidows.com/ Gay and Lesbian Widow Support Site] | |

| − | *[http://www.AllThingsLesbian.com/ All Things Lesbian]

| |

| − | *[http://www.gaylesbiantimes.eu/ Your Gay and Lesbian Community Center] | |

| − | *[http://www.glbthistory.org The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society] | |

| − | *[http://www.shoe.org SHOE Leading Lesbian Online Community]

| |

| − | *[http://www.uptonurc.co.uk Upton United Reformed Gay Church]

| |

| − | *[http://www.sayoni.com Sayoni - An organisation for Asian Queer Women] | |

| − | | |

| − | ===Media depictions===

| |

| − | *[http://www.afterellen.com AfterEllen.Com] Lesbian and Bisexual Women in Entertainment and the Media

| |

| − | *[http://www.clublez.com/movies/ The Encyclopedia of Lesbian Movie Scenes] ''Warning: contains explicit pornographic content'' | |

| − | *[http://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/10/arts/television/10heff.html It's February; Pucker Up, TV Actresses] [[The New York Times]], [[February 10]] [[2005]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Magazines===

| |

| − | *[http://www.curvemag.com/ Curve Magazine] | |

| − | *[http://www.onourbacksmag.com/ On Our Backs]

| |

| − | *[http://www.divamag.co.uk/diva/ Diva] | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| | | | |

| | {{Credits|Lesbian|128362281|}} | | {{Credits|Lesbian|128362281|}} |

A lesbian is a woman who is romantically and sexually attracted solely to other women. Women who are attracted to both women and men are more often referred to as bisexual. An individual's self-identification might not correspond with her behavior, and may be expressed with either, both, or neither of these words. The definition and social norms, including public policy, concerning lesbians have evolved over the course of history.

While male homosexuality has been well documented, albeit controversially, over the centuries and numerous cultures, female sexuality received much less attention. Many, in fact, regarded women as passive partners in sexual encounters, and that same-sex encounters were non-existent and of no interest to women. With the development of studies of sexology as well as the feminist movements in Europe and the United States in the twentieth century, lesbianism became more widely acknowledged. Lesbians have faced similar issues of discrimination, and the desire for same-sex marriage and the option of rearing children that male homosexuals have encountered. While the LGBT movement has gained ground in the acceptance of all people as members of society, the issue of norms of sexual behavior remains controversial.

History

Did you know?

The word "lesbian" is derived from the name of the Greek island of Lesbos, home to the poet

Sappho

The earliest known written references to lesbian or same-sex love between women come from ancient Greece. Sappho (the eponym of "sapphism"), who lived on the island of Lesbos in the sixth century B.C.E., wrote poems which apparently expressed her sexual attraction to other females. Hence the use of the term "Lesbian" to refer to same-sex relationships in women. However, some ancient accounts also describe her as having had love affairs with men. Moreover, Maximus of Tyre wrote that Sappho's relationships with the girls in her school were platonic (non sexual, or based on friendship).

Modern scholarship suggests a parallel between the ancient Greek pederasty (love between men and boys) and the friendships between Sappho and her students in which "both pedagogy and pederasty may have played a role."[1] Lesbian relationships have also been cited in ancient Sparta. Plutarch, writing about the Lacedaemonians, reports that "love was so esteemed among them that girls also became the erotic objects of noble women."[2]

Research by anthropologist Liza Dalby, based mostly on erotic poems exchanged between women, has suggested lesbian relationships were commonplace and socially accepted in Japan during the Heian Period. Accounts of lesbian relationships are also found in poetry and stories from ancient China, but are not documented with the detail given to male homosexuality. During medieval times in Arabia there were reports of relations between harem residents, although these were sometimes suppressed. For example, Caliph Musa al-Hadi ordered the beheading of two slave girls who were surprised during lovemaking.[3]

Culture

The Black Triangle was used to identify "socially unacceptable" women in

concentration camps by the

Nazis. Lesbians were included in this classification. Since then lesbians have appropriated the black triangle as a symbol of defiance against repression and discrimination as gay men have similarly appropriated the pink triangle

Before European sexology emerged at the turn of the twentieth century, female homosexuality remained almost invisible compared to male homosexuality, which was subject to the law and thus more regulated and reported by the press. However with the publication of works by sexologists like Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Havelock Ellis, Edward Carpenter, and Magnus Hirschfeld, the concept of active female homosexuality became better known.

As female homosexuality became more visible it was initially described as a medical condition. In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), Sigmund Freud referred to female homosexuality as "inversion" or "inverts" and characterized female inverts as possessing male characteristics. Freud drew on the "third sex" ideas popularized by Magnus Hirschfeld and others. While Freud admitted he had not personally studied any such "aberrant" patients he placed a strong emphasis on psychological rather than biological causes.

This combination of sexology and psychoanalysis eventually had a lasting impact on the general tone of most lesbian cultural productions. A notable example is the 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall, in which these sexologists are mentioned along with the term "invert." Freud's interpretation of lesbian behavior has since been rejected by most psychiatrists and scholars, although there has been biological research that has provided findings that may bolster a Hirschfeld-ian "third sex" interpretation of same-sex attraction.

During the twentieth century, lesbians such as Gertrude Stein and Barbara Hammer were noted in the U.S. avant-garde art movements, along with figures such as Leontine Sagan in German pre-war cinema. Since the 1890s the underground classic The Songs of Bilitis has been influential on lesbian culture. This book provided a name for the first campaigning and cultural organization in the United States, the Daughters of Bilitis.

During the 1950s and 1960s lesbian pulp fiction was published in the U.S. and U.K., often under "coded" titles such as Odd Girl Out, The Evil Friendship by Vin Packer and the Beebo Brinker series by Ann Bannon. British school stories also provided a haven for "coded" and sometimes outright lesbian fiction.

During the 1970s the second wave of feminist era lesbian novels became more politically oriented. Works often carried the explicit ideological messages of separatist feminism and the trend carried over to other lesbian arts. Rita Mae Brown's debut novel Rubyfruit Jungle was a milestone of this period.

In 1972 the Berkeley, California lesbian journal Libera published a paper entitled "Heterosexuality in Women: its Causes and Cure." Written in deadpan, academic prose, closely paralleling previous psychiatry-journal articles on homosexuality among women, this paper inverted prevailing assumptions about what is normal and deviant or pathological and was widely read by lesbian feminists.

Since the 1980s lesbians have been increasingly visible in mainstream cultural fields such as music (Melissa Etheridge, K.D. Lang, and the Indigo Girls), sports (Martina Navrátilová and Billie Jean King), and in comic books (Alison Bechdel and Diane DiMassa). Lesbian eroticism has flowered in fine art photography and the writing of authors such as Pat Califia, Jeanette Winterson, and Sarah Waters. There is also a significant body of lesbian films. Classic novels such as those by Jane Rule have been reprinted. Moreover, prominent and controversial academic writers such as Camille Paglia and Germaine Greer also identify with lesbianism.

Lesbianism and Feminism

Same-sex married couple at San Francisco Pride 2004.

Historically, many lesbians have been involved in women's rights. Late in the nineteenth century, the term Boston marriage was used to describe romantic unions between women living together while contributing to the suffrage movement. Continuing this tradition, in 2004, Massachusetts became the first American state to legalize same-sex marriages.[4]

During the 1970s and 1980s, with the emergence of modern feminism and the radical feminism movement, lesbian separatism became popular and groups of lesbian women gathered together to live in communal societies. Women such as Kathy Rudy remarked that in her experience, stereotypes and the hierarchies to reinforce them developed in the lesbian separatist collective she lived in, ultimately leading her to leave the group.[5]

There is a body of research and writing on lesbian sexuality which has brought some debate about the control women have over their sexual lives, the fluidity of woman-to-woman sexuality, the redefinition of female sexual pleasure, and the debunking of negative sexual stereotypes. One example of the latter is lesbian bed death, a term invented by sex researcher Pepper Schwartz to describe the supposedly inevitable diminution of sexual passion in long term lesbian relationships; this notion has been rejected by many lesbians, who pointed out that passion tends to diminish in almost any relationship and many lesbian couples have reported happy and satisfying sex lives.

Transgender issues

The relationship between lesbianism and lesbian-identified transgender or transsexual women has been a turbulent one, with historically negative attitudes. Some lesbian groups openly welcome transsexual women and may even welcome any member who identifies as lesbian, but a few groups do not welcome transwomen.

Disputes in defining the term "lesbian" along with enforced exclusions from lesbian events and spaces have been numerous. Some who hold a non-inclusionist attitude often make reference to strong, typically second-wave feminist ideas such as those of Mary Daly, who has described post-operative male-to-female (MTF) transsexuals as "'constructed women." They may attribute transsexualism to mechanisms of patriarchy or do not recognize a MTF transsexual's identification as female and lesbian. By defining "lesbian" through these views, they defend the non-inclusion of women with transsexual or transgender-backgrounds.

Inclusionists claim these attitudes are inaccurate and derive from fear and distrust, or that the motivations and attitudes of transgender or transsexual lesbians are not well understood, and so they defend the inclusion of transwomen into lesbianism and lesbian spaces.

One incident due to this divisiveness arose during the early 1990s in Australia, when the wider lesbian community raised money to purchase a building devoted to lesbian women called The Lesbian Space Project. Before the organization bought the building, a debate over inclusion of transwomen polarized the lesbian community, the building was later closed, the funds were invested and instead generated money for an annual Australian lesbian grants program called LInc (Lesbians Incorporated).

Public policy

In Western societies, explicit prohibitions on women's homosexual behavior have been markedly weaker than those on men's homosexual behavior.

In the United Kingdom, lesbianism has never been illegal. In contrast, sexual activity between males was not made legal in England and Wales until 1967. It is said that lesbianism was left out of the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 because Queen Victoria did not believe sex between women was possible, although this story may be apocryphal.[6] A 1921 proposal put forward by Frederick Macquisten MP to criminalize lesbianism was rejected by the House of Lords; during the debate, Lord Birkenhead, then Lord Chancellor argued that 999 women out of a thousand had "never even heard a whisper of these practices."[7]

In 1928, the lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness was banned for obscenity in a highly publicized trial, not for any explicit sexual content but because it made an argument for acceptance.[8] Meanwhile other, less political novels with lesbian themes continued to circulate freely,[9]

Jewish religious teachings condemn male homosexual behavior but say little about lesbian behavior. However, the approach in the modern state of Israel, with its largely secular Jewish majority, does not outlaw or persecute gay sexual orientation; marriage between gay couples is not sanctioned but common law status and official adoption of a gay person's child by his or her partner have been approved in precedent court rulings (after numerous high court appeals).

Western-style homosexuality is rarely tolerated elsewhere in the Muslim world, with the possible exception of Turkey. It is punishable by imprisonment, lashings, or death in Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Though the law against lesbianism in Iran has reportedly been revoked or eased, prohibition of male homosexuality remains.

Reproduction and parenting rights

Family issues were significant concerns for lesbians when gay activism became more vocal in the 1960s and 1970s. Custody issues in particular were of interest since often courts would not award custody to mothers who were openly homosexual.

Also, many lesbian couples seek to have children through adoption, domestically or internationally, or provide a home as a foster parent, but this is not legal in every country. Access to in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments is also the subject of debate in many countries.

Notes

- ↑ Ellen Greene (ed.), Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996, ISBN 0520201957).

- ↑ "Life of Lycurgus" 18.4.

- ↑ C.E. Bosworth (trans.), The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30 (Albany: SUNY Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0887065644).

- ↑ Jone Johnson Lewis, Boston Marriage: Women Living Together, 19th/20th Century Style ThoughtCo, July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ↑ Kathy Rudy, Radical Feminism, Lesbian Separatism, and Queer Theory Feminist Studies 27(1) (Spring, 2001): 190-222.

- ↑ Terry Castle, The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993, ISBN 0231076525), 11, 66.

- ↑ Laura Doan, Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture New York: Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 0231110073), 56-60.

- ↑ Sir Chartres Biron, 1928, "Judgment," Laura Doan, and Jay Prosser, Palatable Poison: Critical Perspectives on The Well of Loneliness (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 0231118759), 39-49.

- ↑ Jeanette H. Foster, Sex Variant Women in Literature: A Historical and Quantitative Survey (New York: Vantage Press, 1956), 287.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abelove, Henry. The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415905192

- Bosworth C.E. (trans.). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30. Albany: SUNY Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0887065644

- Castle, Terry. The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. ISBN 0231076525

- Clifford, Denis. A Legal Guide for Lesbian & Gay Couples. NOLO, 2007. ISBN 1413306292

- Clunis, D. Merilee. Lesbian Couples: A Guide to Creating Healthy Relationships. Seal Press, 2004. ISBN 1580051316

- Doan, Laura. Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001. ISBN 0231110073)

- Doan, Laura, and Jay Prosser. Palatable Poison: Critical Perspectives on The Well of Loneliness. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001. ISBN 0231118759

- Foster, Jeanette H. Sex Variant Women in Literature: A Historical and Quantitative Survey. New York: Vantage Press, 1956.

- Freud, Sigmund. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. Alicia Editions, 2020. ISBN 978-2357284852

- Greene, Ellen (ed.). Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN 0520201957

- Stevens, Tracey. How To Be A Happy Lesbian: A Coming Out Guide. Amazing Dreams Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0971962804

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.