Gay rights movement

The gay rights movement, or LGBT movement refers to myriad organizations, groups, and people broadly fighting for the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people (LGBT). The different segments of this social movement often share related goals of social acceptance, equal rights, liberation, and feminism. Others focus on building specific LGBT communities or working towards sexual liberation in broader society. LGBT movements organized today are made up of a wide range of political activism and cultural activity, such as lobbying and street marches; social groups, support groups, and community events; magazines, films, and literature; academic research and writing; and even business activity. While most activists are peaceful, there has been violence associated with this movement, as much on the part of those opposing as those promoting the rights.

While open homosexuality, or at least bisexuality, has been accepted in many cultures, most Jewish, Christian, and Muslim societies have regarded such behavior as sinful, and rejected those who practice it, punishing them even with death. In more recent times, however, while many still regard it as wrong, they have adopted the attitude that God's grace is for all people, and see homosexuals primarily as human beings deserving of human rights. The movement for LGBT rights emerged in the twentieth century, as many human rights issues became prominent. This century marks the age in which the rights of all individuals began to be recognized in cultures around the world, a significant step in the establishment of a world of peace and harmony.

Goals and strategies

The LGBT community is as disparate as any other large body, and as such its members have different views regarding the goals toward which activists should aim and what strategies they should use in accomplishing these ends. Nevertheless, somewhat of a consensus has emerged among contemporary activists. Sociologist Mary Bernstein writes: "For the lesbian and gay movement, then, cultural goals include (but are not limited to) challenging dominant constructions of masculinity and femininity, homophobia, and the primacy of the gendered heterosexual nuclear family (heteronormativity). Political goals include changing laws and policies in order to gain new rights, benefits, and protections from harm."[1] Bernstein emphasizes that activists seek both types of goals in both the civil and political spheres.

As with other social movements, there is also conflict within and between LGBT movements, especially about strategies for change and debates over exactly who comprises the constituency that these movements represent. There is debate over to what extent lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgendered people, intersexed people, and others share common interests and a need to work together. Leaders of the lesbian and gay movement of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s often attempted to hide butch lesbians, feminine gay men, transgendered people, and bisexuals from the public eye, creating internal divisions within LGBT communities.[2]

LGBT movements have often adopted a kind of identity politics that sees lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and/or transgender people as a fixed class of people; a minority group or groups. Those using this approach aspire to liberal political goals of freedom and equal opportunity, and aim to join the political mainstream on the same level as other groups in society.[3] In arguing that sexual orientation and gender identity are innate and cannot be consciously changed, attempts to change gay, lesbian, and bisexual people into heterosexuals ("reparative therapy") are generally opposed.

However, others within LGBT movements have criticized identity politics as limited and flawed,[4] and have instead aimed to transform fundamental institutions of society (such as lesbian feminism) or have argued that all members of society have the potential for same-sex sexuality (such as Adolf Brand or Gay Liberation) or a broader range of gender expression (such as the transgender writing of Kate Bornstein). Some elements of the movement have argued that the categories of gay and lesbian are restrictive, and attempted to deconstruct those categories, which are seen to "reinforce rather than challenge a cultural system that will always mark the nonheterosexual as inferior."[1]

History

The history of the gay rights movement is shaped around both seminal events and people. Important framers of the movement include Karl Ulrichs, who wrote about gay rights in the 1860s, the revived western culture following World War II, the new social movements of the 1960s, and the unprecedented level of acceptance of the LGBT community in the later twentieth century.

Before 1860

In eighteenth and nineteenth century Europe, same-sex sexual behavior and cross-dressing were widely considered to be socially unacceptable, and were serious crimes under sodomy and sumptuary laws. Any organized community or social life was underground and secret. Thomas Cannon wrote what may be the earliest published defense of homosexuality in English, Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify'd (1749). Social reformer Jeremy Bentham wrote the first known argument for homosexual law reform in England around 1785, at a time when the legal penalty for "buggery" was death by hanging.[5] However, he feared reprisal, and his powerful essay was not published until 1978. The emerging currents of secular humanist thought which had inspired Bentham also informed the French Revolution, and when the newly-formed National Constituent Assembly began drafting the policies and laws of the new republic in 1790, groups of militant 'sodomite-citizens' in Paris petitioned the Assemblée nationale, the governing body of the French Revolution, for freedom and recognition.[6] In 1791, France became the first nation to decriminalize homosexuality, probably thanks in part to the homosexual Jean Jacques Régis de CambacérÚs who was one of the authors of the Napoleonic code.

In 1833, an anonymous English-language writer wrote a poetic defense of Captain Nicholas Nicholls, who had been sentenced to death in London for sodomy:

- Whence spring these inclinations, rank and strong?

- And harming no one, wherefore call them wrong?[6]

Three years later in Switzerland, Heinrich Hoessli published the first volume of Eros: Die Mannerliebe der Griechen ("Eros: The Male-love of the Greeks"), another defense of same-sex love.[6]

1860-1944

Modern historians usually look to German activist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs as the pioneer of the LGBT rights movement. Ulrichs came out publicly and began publishing books about same-sex love and gender variance in the 1860s, a few years before the term "homosexual" was first published in 1869. Ulrichs' Uranians were people with a range of gender expressions and same-sex desires; he considered himself "a female psyche in a male body."

From the 1870s, social reformers in other countries had begun to take up the Uranian cause, but their identities were kept secret for fear of reprisal. A secret British society called the "Order of Chaeronea" campaigned for the legalization of homosexuality, and counted playwright Oscar Wilde among its members in the last decades of the nineteenth century.[7] In the 1890s, English socialist poet Edward Carpenter and Scottish anarchist John Henry Mackay wrote in defense of same-sex love and androgyny; Carpenter and British homosexual rights advocate John Addington Symonds contributed to the development of Havelock Ellis's groundbreaking book Sexual Inversion, which called for tolerance towards "inverts" and was suppressed when first published in England.

In Europe and America, a broader movement of "free love" was also emerging from the 1860s among first-wave feminists and radicals of the libertarian Left. They critiqued Victorian sexual morality and the traditional institutions of family and marriage that were seen to enslave women. Some advocates of free love in the early twentieth century also spoke in defense of same-sex love and challenged repressive legislation, such as the Russian anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman.

In 1898, German doctor and writer Magnus Hirschfeld formed the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee to campaign publicly against the notorious law "Paragraph 175," which made sex between men illegal. Adolf Brand later broke away from the group, disagreeing with Hirschfeld's medical view of the "intermediate sex," seeing male-male sex as merely an aspect of manly virility and male social bonding. Brand was the first to use "outing" as a political strategy, claiming that German Chancellor Bernhard von BĂŒlow engaged in homosexual activity.

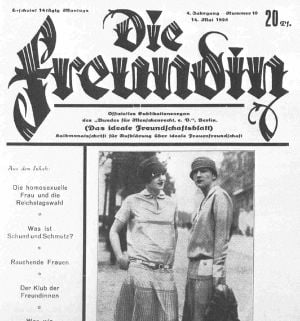

The 1901 book, Sind es Frauen? Roman ĂŒber das dritte Geschlecht (Are These Women? Novel about the Third Sex) by AimĂ©e Duc was as much a political treatise as a novel, criticizing pathological theories of homosexuality and gender inversion in women.[8] Anna RĂŒling, delivering a public speech in 1904 at the request of Hirschfeld, became the first female Uranian activist. RĂŒling, who also saw "men, women, and homosexuals" as three distinct genders, called for an alliance between the women's and sexual reform movements, but this speech is her only known contribution to the cause. Women only began to join the previously male-dominated sexual reform movement around 1910, when the German government tried to expand Paragraph 175 to outlaw sex between women. Heterosexual feminist leader Helene Stöcker became a prominent figure in the movement.

Hirschfeld, whose life was dedicated to social progress for homosexual and transgender people, formed the Institut fĂŒr Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexology) in 1919. The institute conducted an enormous amount of research, saw thousands of transgender and homosexual clients at consultations, and championed a broad range of sexual reforms including sex education, contraception, and women's rights. However, the gains made in Germany would soon be drastically reversed with the rise of Nazism, and the institute and its library were destroyed in 1933. The Swiss journal Der Kreis was the only part of the movement to continue through the Nazi era.

In the United States, several secret or semi-secret groups were formed explicitly to advance the rights of homosexuals as early as the turn of the twentieth century, but little is known about them. A better documented group is Henry Gerber's Society for Human Rights formed in Chicago in 1924, which was quickly suppressed.[9]

1945-1968

Immediately following World War II, a number of homosexual rights groups came into being or were revived across the Western world, in Britain, France, Germany, Holland, the Scandinavian countries, and the United States. These groups usually preferred the term homophile to "homosexual," emphasizing love over sex. The homophile movement began in the late 1940s, with groups in the Netherlands and Denmark, and continued throughout the 1950s and 1960s with groups in Sweden, Norway, the United States, France, Britain and elsewhere. ONE, Inc., the first public homosexual organization in the U.S, was bankrolled by the wealthy transsexual man Reed Erickson.[10] A U.S. transgender-rights journal, Transvestia: The Journal of the American Society for Equality in Dress, also published two issues in 1952.

The homophile movement lobbied within established political systems for social acceptability; radicals of the 1970s would later disparage the homophile groups for being assimilationist. Any demonstrations were orderly and polite. By 1969, there were dozens of homophile organizations and publications in the U.S, and a national organization had been formed, but they were largely ignored by the media. A 1965 gay march held in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, according to some historians, marked the beginning of the modern gay rights movement. Meanwhile in San Francisco in 1966, transgender street prostitutes in the poor neighborhood of Tenderloin rioted against police harassment at a popular all-night restaurant, Gene Compton's Cafeteria.

1969-1974

The new social movements of the sixties, such as the Black Power and anti-Vietnam war movements in the U.S, the May 1968 insurrection in France, and Women's Liberation throughout the Western world, inspired some LGBT activists to become activist, and the Gay Liberation Movement emerged towards the end of the decade. This new radicalism is often attributed to the Stonewall riots of 1969, when a group of transgender, lesbian, and gay male patrons at a bar in New York resisted a police raid.[9] Although Gay Liberation was already underway, Stonewall certainly provided a rallying point for the fledgling movement.

Immediately after Stonewall, such groups as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), in part founded by Morris Kight, and the Gay Activists' Alliance (GAA) were formed. Their use of the word "gay" represented a new unapologetic defianceâas an antonym for "straight" ("respectable sexual behavior"), it encompassed a range of non-normative sexualities and gender expressions, such as transgender street prostitutes, and sought ultimately to free the bisexual potential in everyone, rendering obsolete the categories of homosexual and heterosexual.[11][12] According to Gay Lib writer Toby Marotta, "their Gay political outlooks were not homophile but liberationist."[13] "Out, loud and proud," they engaged in colorful street theatre.[14] The GLFâs "A Gay Manifesto" set out the aims for the fledgling gay liberation movement, and influential intellectual Paul Goodman published âThe Politics of Being Queerâ (1969). Chapters of the GLF were established across the U.S. and in other parts of the Western world. The Front Homosexuel d'Action RĂ©volutionnaire was formed in 1971 by lesbians who split from the Mouvement Homophile de France in 1971. One of the values of the movement was gay pride. Organized by an early GLF leader Brenda Howard, the Stonewall riots were commemorated by annual marches that became known as Gay pride parades. From 1970 activists protested the classification of homosexuality as a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association in their DSM, and in 1974, it was replaced with a category of "sexual orientation disturbance" then "ego-dystonic homosexuality," which was also deleted, although "gender identity disorder" remains.

1975-1986

From the anarchistic Gay Liberation Movement of the early 1970s arose a more reformist and single-issue "Gay Rights Movement," which portrayed gays and lesbians as a minority group and used the language of civil rightsâin many respects continuing the work of the homophile period.[15] In Berlin, for example, the radical Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin was eclipsed by the Allgemeine Homosexuelle Arbeitsgemeinschaft.[16] This period also saw a shift away from transgender issues, and butch "bar dykes" and flamboyant "street queens" came to be seen as negative stereotypes of lesbians and gays. Veteran activists such as Sylvia Rivera and Beth Elliot were sidelined or expelled because they were transsexual. During this period, the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA) was formed (1978), and it continues to campaign for lesbian and gay human rights with the United Nations and individual national governments.

Lesbian feminism, which was most influential from the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, encouraged women to direct their energies toward other women rather than men, and advocated lesbianism as the logical result of feminism.[17] As with Gay Liberation, this understanding of the lesbian potential in all women was at odds with the minority-rights framework of the Gay Rights movement. Many women of the Gay Liberation movement felt frustrated at the domination of the movement by men and formed separate organisations; some who felt gender differences between men and women could not be resolved developed "lesbian separatism," influenced by writings such as Jill Johnston's 1973 book Lesbian Nation. Disagreements between different political philosophies were, at times, extremely heated, and became known as the lesbian sex wars, clashing in particular over views on sadomasochism, prostitution, and transsexuality. The term "gay" came to be more strongly associated with homosexual males.

1987-present

Some historians consider that a new era of the gay rights movement began in the 1980s with the emergence of AIDS, which decimated the leadership and shifted the focus for many.[10] This era saw a resurgence of militancy with direct action groups like ACT UP (formed in 1987), and its offshoots Queer Nation (1990) and the Lesbian Avengers (1992). Some younger activists, seeing "gay and lesbian" as increasingly normative and politically conservative, began using the word queer as a defiant statement of all sexual minorities and gender variant peopleâjust as the earlier liberationists had done with the word "gay." Less confrontational terms that attempt to reunite the interests of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transpeople also became prominent, including various acronyms like LGBT, LGBTQ, and LGBTI.

In the 1990s, organizations began to spring up in non-western countries, such as Progay Philippines, which was founded in 1993 and organized the first Gay Pride march in Asia on June 26, 1994. In many countries, LGBT organizations and transgender and homosexual activists face extreme opposition from the state. Also, many activists attempted to turn the attention of the West to the situation of queers in non-western countries.

The 1990s also saw a rapid expansion of transgender rights movements across the globe. Hijra activists campaigned for recognition as a third sex in India and Travesti groups began to organize against police brutality across Latin America, while activists in the United States formed militant groups such as Transexual Menace. An important text was Leslie Feinberg's "Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come," published in 1992. 1993 is considered to mark the beginning of a new movement of intersexuals, with the founding of the Intersex Society of North America by Cheryl Chase.

In many cases, LGBTI rights movements came to focus on questions of intersectionality, the interplay of oppressions arising from being both queer and underclass, colored, disabled, and so on.

In the twenty-first century same-sex marriage came to be legally accepted in many countries, beginning with the Netherlands in 2001, and rapidly increasing over the next two decades to over 30 countries.[18]

Opposition

Those opposed to the LGBT rights movement adopt this position for a number of reasons. Some people are morally opposed to anything other than traditional heterosexuality and are therefore opposed to anything involving homosexuality, bisexuality, or anything in between. Other than this, there exist people who are opposed to gay rights from a legal perspective. More often than not these people support similar, but not identical, rights for LGBT people. These opponents would argue for such things as civil unions versus marriage. Others believe that being gay or lesbian is a choice rather than naturally determined, and because of this people should not be treated the same as those who follow "natural" impulses.

LGBT movements are opposed by a variety of individuals and organizations. They may have a personal, moral, or religious objection to homosexuality. Studies have consistently shown that people with negative attitudes towards lesbians and gays are more likely to be male, older, religious, politically conservative, and have little close personal contact with out gay men and lesbians. Studies find that heterosexual men usually exhibit more hostile attitudes toward gay men and lesbians than do heterosexual women.[19] They are also more likely to have negative attitudes towards other minority groups[20] and support traditional gender roles.[21]

Nazi opposition

When the German Nazi party came to power in 1933, one of the party's first acts was to burn down the Institut fĂŒr Sexualwissenschaft, an advocate of sexual liberation. Subsequently, the Nazis also began sending homosexuals to concentration camps. The organized gay rights movement would not rise again until after the Second World War.

Conservative opposition to LGBT rights in the U.S.

Anita Bryant organized the first major opposition movement to gay rights in America, based on fundamentalist Christian values.[22] The group used various slogans that played off the fear that gay people were interested in "recruiting" or molesting children into a "life-style." A common slogan of the campaign was "Homosexuals cannot reproduceâso they must recruit." The Bryant campaign was successful in repealing many of the city anti-discrimination laws, and in proposing other citizen initiatives, such as a failed California ballot question designed to ban homosexuals or anyone who endorsed gay rights from being a public school teacher. The name of this group was "Save Our Children," and its most successful campaign resulted in the repealing of Dade County's Civil Rights Ordinance.[23]

From the late 1970s onwards, Conservative Christian organizations such as the 700 Club, Focus on the Family, Concerned Women For America, and the Christian Coalition built strong lobbying and fundraising organizations to oppose the gay rights movement's goals.

Conservative Christian organizations behaved similarly in other nations. In the 1980s organizations opposed to gay rights successfully persuaded the British Conservative Party to enact Section 28, which banned public schools from "promoting homosexuality" or endorsing same-sex marriages.[24]

Boy Scouts of America

In 1978 the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) excluded gay and bisexual people from its organizations, generally for Scoutmasters but also for scouts in leadership positions. Their rationale was that homosexuality is immoral, and that scouts are expected to have certain moral standards and values, as the Scout Oath and Scout Law requires boys to be "morally straight."[25]

The ban stood for decades, withstanding numerous legal challenges. In 2000, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale that the Boy Scouts of America is a private organization, and as such can decide its own membership rules. Scouts for Equality was founded in 2012 to increase public awareness of BSA's discriminatory practices against gays in scouting, and to urge BSA leaders to end the ban as quickly as possible. On May 23, 2013, the BSA ended its membership ban on gay youth, but the ban on adults remained in effect. On July 27, 2015, the BSA ended the ban on gay adults. There was no formal policy on transgender individuals, however, following an incident in 2016, on January 30, 2017 the BSA decided to accept boys based on the gender identity on their application.[26]

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces' "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" (DADT) was the official United States policy on military service of non-heterosexual people. Instituted during the Clinton administration, the policy was issued under Department of Defense Directive 1304.26 on December 21, 1993. This policy required gay men and lesbians to be discharged from the armed forces if they came out, but did not allow the military to specifically question people about their sexual orientation. The policy prohibited people who "demonstrate a propensity or intent to engage in homosexual acts" from serving in the armed forces of the United States, because their presence "would create an unacceptable risk to the high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion that are the essence of military capability."[27]

The policy was in effect from February 28, 1994, until September 20, 2011 when it was repealed under the Obama administration.[28]

Psychological

Most LGBT groups see homosexuality as natural and not a choice. A resolution adopted by the American Psychological Association in August 1997 states that "homosexuality is not a mental disorder."[29]

While mainstream psychology has come around to the view that homosexuality is an innate condition, although a dissenting minority regard it as a disorder and have developed specialized therapies that can enable those who are willing to deal with their same-sex attraction and settle into a heterosexual lifestyle.[30] The idea of reparative therapy considers homosexuality to be a behavior that can be modified, rather than a permanent orientation.[31]

Religious and philosophical

Christian,[32] Jewish,[33] and Islamic[34] social conservatives view homosexuality as a sin, and its practice and acceptance in society as a weakening of moral standards. This is a primary reason why many religious social conservatives oppose the gay rights movement.

Some also cite natural law, sometimes called "God's law" or "nature's law," when opposing the gay rights movement.[35]

Homosexuality is condemned and illegal in many modern Muslim nations such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Iran, Mauritania, Sudan, and Somalia. These laws are based on such passages from the Qur'an as

And Lut, when he said to his tribe: "Do you commit an obscenity not perpetrated before you by anyone in all the worlds? You come with lust to men instead of women. You are indeed a depraved tribe." The only answer of his tribe was to say: "Expel them from your city! They are people who keep themselves pure!" So We rescued him and his family-except for his wife. She was one of those who stayed behind. We rained down a rain upon them. See the final fate of the evildoers! (7:80-84).

Buddhists believe people should refrain from sexual misconduct, with varying opinion as to whether or not this refers to homosexuality. Likewise, opinion varies within Judaism. Orthodox Jews point to the book of Leviticus, which describes homosexuality as an "abomination," though Reform and Reconstruction Judaism both see nothing wrong with homosexuality. These opinions are not necessarily held by all members of these sects and the status of homosexuality remains hotly contested among members in many.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 Mary Bernstein, "Identities and Politics: Toward a Historical Understanding of the Lesbian and Gay Movement," Social Science History 26 (2002):3.

- â C. Bull and J. Gallagher, Perfect Enemies: The Religious Right, the Gay Movement, and the Politics of the 1990s (New York, NY: Crown, 1996).

- â Andrew Sullivan, Same-Sex Marriage: Pro and Con (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 1400078660).

- â Dennis Altman, "The gay movement ten years later," Nation, November 13, 1982: 494â96.

- â Jeremy Bentham, "Offences Against One's Self" Journal of Homosexuality 3:4(1978):389-405. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mark Blasius and Shane Phelan (eds.), We Are Everywhere: A Historical Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics (New York, NY: Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0415908590).

- â Neil McKenna, The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde: An Intimate Biography (London: Century, 2003, ISBN 0712669868).

- â Claudia Breger, "Feminine Masculinities: Scientific and Literary Representations of 'Female Inversion' at the Turn of the Twentieth Century," Journal of the History of Sexuality 14(1/2) (2005): 76-106.

- â 9.0 9.1 Vern Bullough, "When Did the Gay Rights Movement Begin? Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â 10.0 10.1 Vern L. Bullough (ed.), Before Stonewall (The Haworth Press, Inc, 2002). Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â Dennis Altman, Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation (NYU Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0814706237).

- â Barry D. Adam, The Rise of a Gay and Lesbian Movement (New York, NY: Twayne Publishers, 1997, ISBN 0805738649).

- â Toby Marotta, The Politics of Homosexuality (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1981, ISBN 0395294770).

- â John Gallagher and Chris Bull, Perfect Enemies The Washington Post (1996). Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â S. Epstein, "Gay and lesbian movements in the United States: Dilemmas of identity, diversity, and political strategy," in Barry D. Adam, J. Duyvendak, and A. Krouwel (eds.), The Global Emergence of Gay and Lesbian Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-1566396455).

- â Gert Hekman, Harry Oosterhuis, and James Steakley, "Leftist Sexual Politics and Homosexuality: A Historical Overview," Journal of Homosexuality 29 (2/3).

- â Adrienne Rich, "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence," Signs 5(1980): 631-660.

- â Marriage Equality Around the World Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â Beverly Greene and Gregory Herek (eds.), Lesbian and Gay Psychology: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications (Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994, ISBN 978-0803953123).

- â John C. Gonsiorek and James D. Weinrich (eds.), Homosexuality: Research Implications for Public Policy (Newbury Park, CA: SAGE, 1991, ISBN 978-0803937642).

- â K.B. Kyes and L. Tumbelaka, Comparison of Indonesian and American college students' attitudes toward homosexuality. Psychological Reports 74 (1994): 227-237.

- â Louis-Georges Tin, Dictionary of Homophobia: A Global History of Gay & Lesbian Experience (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1551522296).

- â Anita Bryant, The Anita Bryant Story (Fleming H. Revell Company, 1979, ISBN 978-0800783471).

- â The Section 28 Battle BBC News (July 24, 2000). Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â U.S. Scouts, Boy Scout Oath, Boy Scouts of America. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â About Us Scouts for Equality. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â 10 U.S. Code § 654 - Repealed. Pub. L. 111â321, §âŻ2(f)(1)(A), Dec. 22, 2010, 124 Stat. 3516 Legal Information Institute. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- â Obama certifies end of military's gay ban NBC News (July 22, 2011). Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- â Neel Burton, When Homosexuality Stopped Being a Mental Disorder Psychology Today (July 3, 2023). Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â Richard Cohen, Gay Children, Straight Parents: A Plan for Family Healing (International Healing Foundation Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0963705815).

- â J, Drescher, I'm your handyman: a history of reparative therapies J. Homosex. 36(1) (1998):19-42. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â Lehman Strauss, "Homosexuality: The Christian Perspective." Bible.org. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â Rabbi Avi Shafran, "Jewish Law: Marital Problems," Jewish Law Commentary: Examining Halacha, Jewish Issues, and Secular Law. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â Islam's Clear Position on Homosexuality Australian National Imams Council (March 10, 2018). Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- â "Homosexuality: Natural Law," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adam, Barry D. The Rise of a Gay and Lesbian Movement. Revised edition. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers, 1997. ISBN 0805738649

- Adam, Barry D., J. Duyvendak, and A. Krouwel (eds.). The Global Emergence of Gay and Lesbian Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-1566396455

- Altman, Dennis. Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. NYU Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0814706237

- Blasius, Mark, and Shane Phelan (eds.). We Are Everywhere: A Historical Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics. New York, NY: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415908590

- Bryant, Anita. The Anita Bryant Story. Fleming H. Revell Company, 1979. ISBN 978-0800783471

- Bull, C. and J. Gallagher. Perfect Enemies: The Religious Right, the Gay Movement, and the Politics of the 1990s. New York, NY: Diane Publishing Company, 1996. ISBN 978-0788196133

- Caramagno, Thomas C. Irreconcilable Differences? Intellectual Stalemate in the Gay Rights Debate. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002. ISBN 0275977218.

- Carter, David. Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution. New York, NY: St Martinâs Press, 2004. ISBN 0312200250.

- Cohen, Richard. Gay Children, Straight Parents: A Plan for Family Healing. International Healing Foundation Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0963705815

- Cruikshank, Margaret. The Gay and Lesbian Liberation Movement. New York, NY: Routledge, Chapman and Hall, 1992. ISBN 0415906482

- Duberman, Martin. Stonewall. New York: Plume, 1994. ISBN 0452272068

- Gonsiorek, John C., and James D. Weinrich (eds.). Homosexuality: Research Implications for Public Policy. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE, 1991. ISBN 978-0803937642

- Greene, Beverly, and Gregory Herek (eds.). Lesbian and Gay Psychology: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994. ISBN 978-0803953123

- Lauritsen, John, and David Thorstad. The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935). Revised edition. Ojai, CA: Times Change Press, 1995. ISBN 0878100415

- Marotta, Toby. The Politics of Homosexuality. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1981. ISBN 0395294770

- McKenna, Neil. The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde: An Intimate Biography. London: Century, 2003. ISBN 0712669868

- Miller, Neil. Out of the Past: Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the Present. New York, NY: Alyson Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1555838706

- Sullivan, Andrew. Same-Sex Marriage: Pro and Con. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2004. ISBN 1400078660

- Tin, Louis-Georges. Dictionary of Homophobia: A Global History of Gay & Lesbian Experience. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1551522296

- Vaid, Urvashi. Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation. New York, NY: Anchor, 1996. ISBN 978-0385472999

External links

All links retrieved April 17, 2024.

- Gallagher, John & Chris Bull, Perfect Enemies, 1996.

- Gay Rights History.com.

- LGBTQ Activism Library of Congress

- LGBTQ Rights ACLU.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.